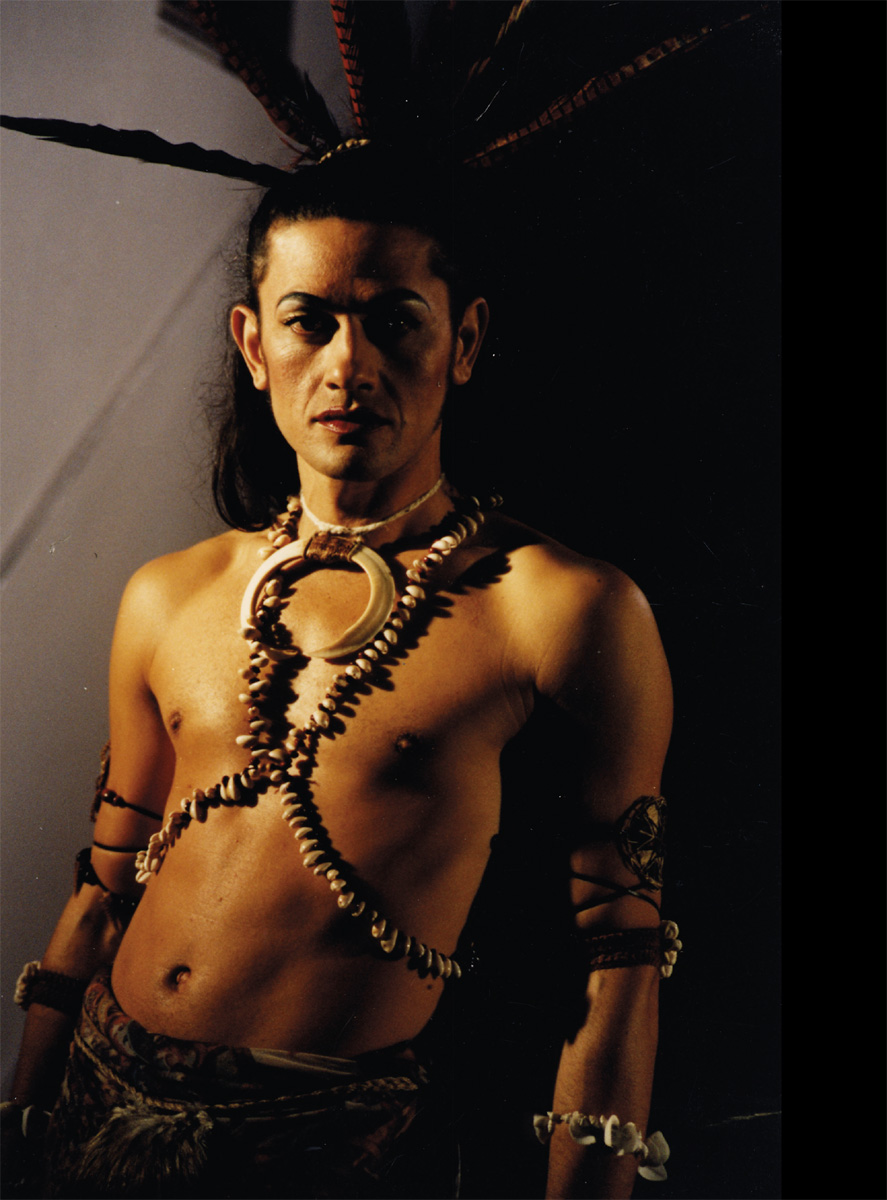

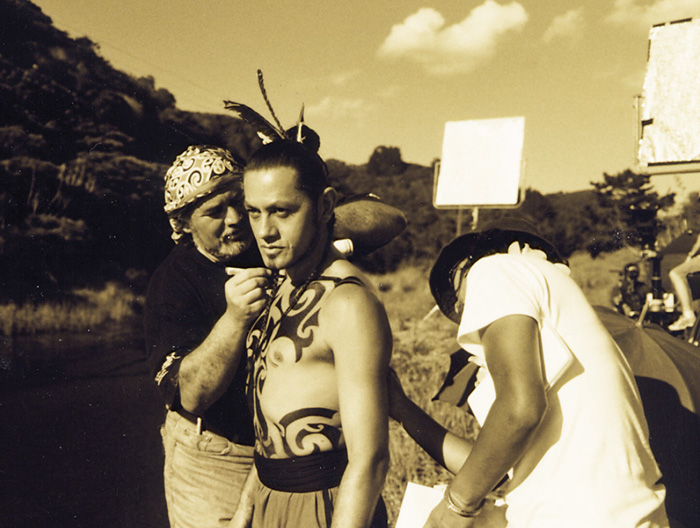

Photo shoot for Jan Hellriegel’s ‘Geraldine’ music video, 1995. Photo by Christine Webster, costume by Pacific Sisters.

CHAPTER SIX

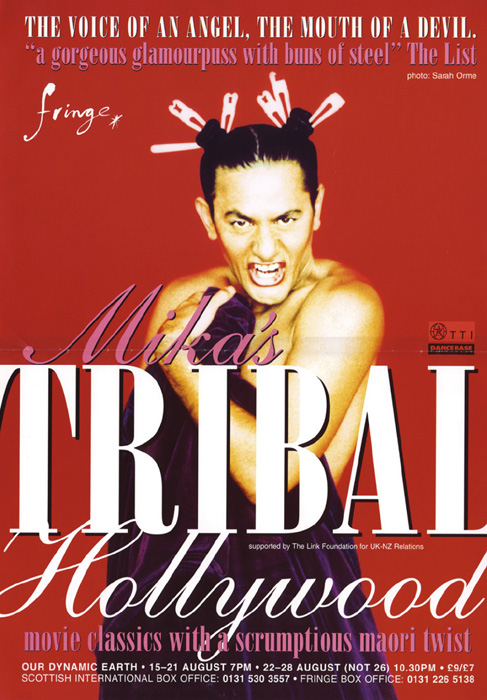

TRIBAL HOLLYWOOD

No we’re not going to be your chocolate-coated fantasies any more, Captain.

— Mika and the UhuRas poster

Better to be a flash in the pan, than never to have been a flash.

— Mika, to Kim Hill

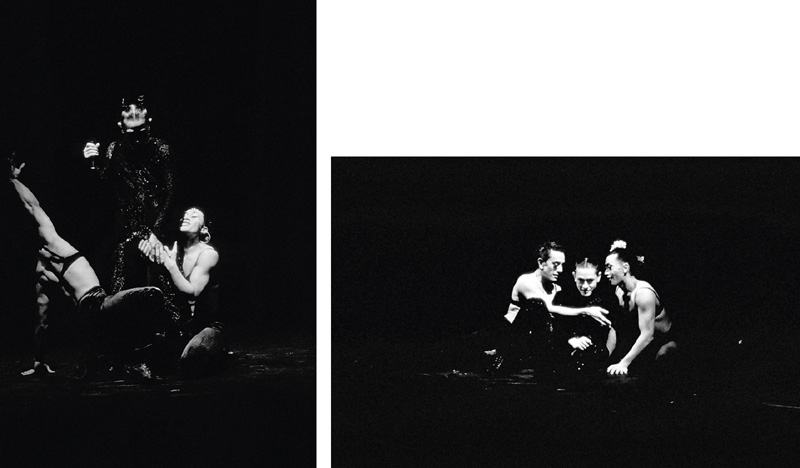

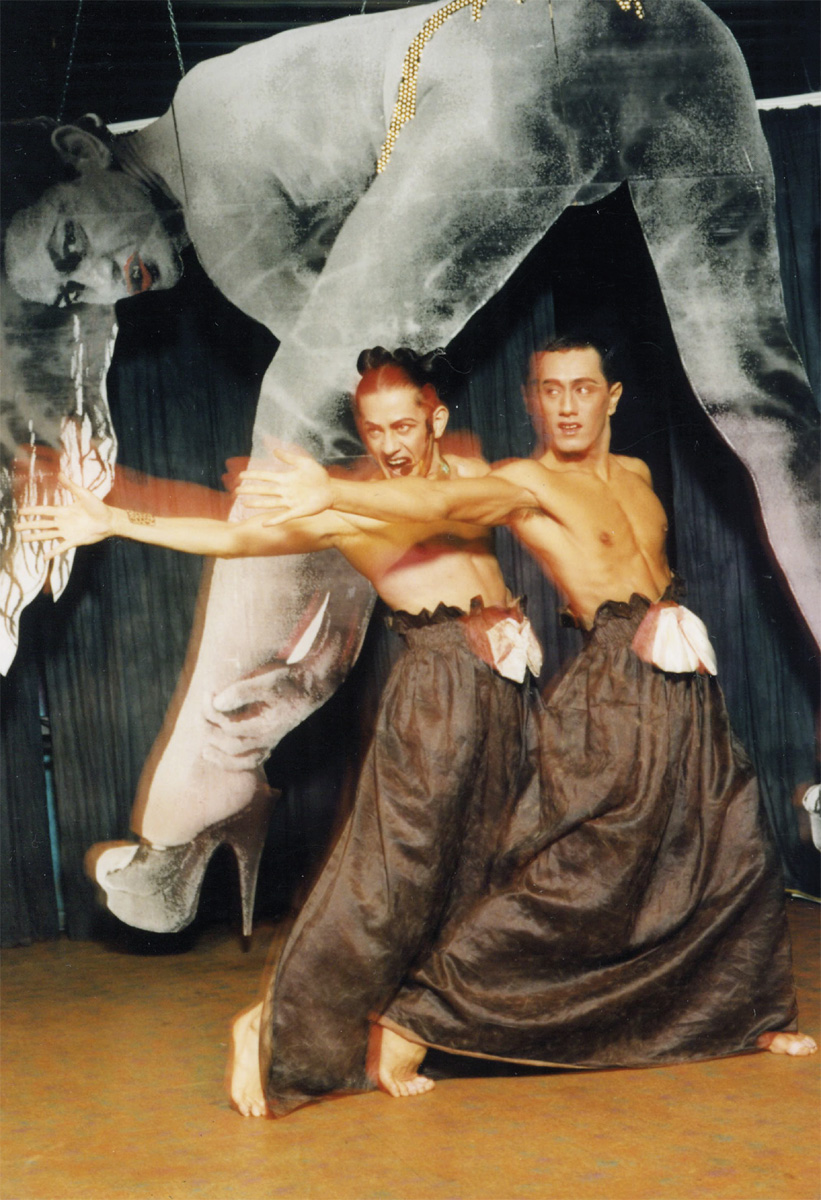

THE STARFISH ENTERPRISE

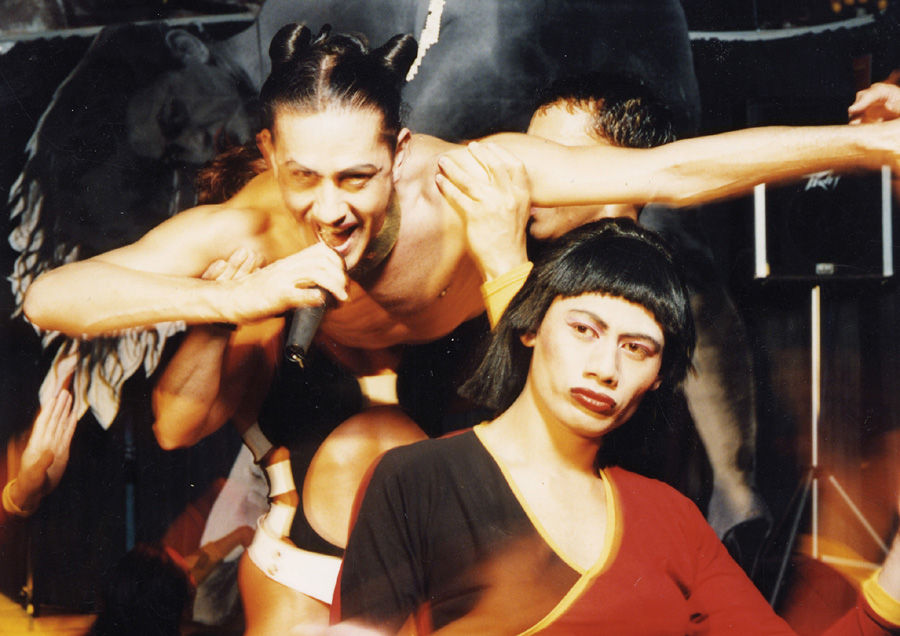

They were the darlings of the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in 1997: Mika and the UhuRas, Taane Mete and Taiaroa Royal. The posters and images from the trio’s various performances, in New Zealand and elsewhere, show the UhuRas in various drag mock-ups. They’re wearing parodies of Nichelle Nichols’ Star Trek costume, and also eccentrically flamboyant chiffons, feathers and sequins. Mika occasionally takes up the Star Trek dress alongside them, but he’s mostly undressed in shiny leggings and not much else. The exuberance in these pictures is palpable. They’re visibly gleeful and cheekily naughty, caught in mid-dance and sometimes in mid-leap, microphones in hands, arms and legs at all angles. It’s performance as party, looking full of life and love for each other, with an open-armed invitation to the audience to play along.

Performance scholar Mark James Hamilton, who came to collaborate with Mika after seeing him performing with the UhuRas in Edinburgh, has written at length about the experience. Hamilton recalls that Mika

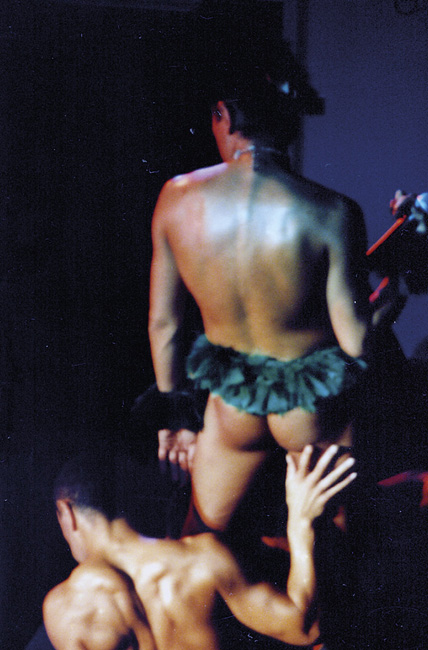

wore a green catsuit cut to expose his buttocks, and he was flanked by two Māori drag queens in bikinis. The men’s costumes revealed their muscularity, which was further accentuated when they slapped their chests and thighs vigorously and arrested their punches mid-flight as they performed the show’s final haka.1

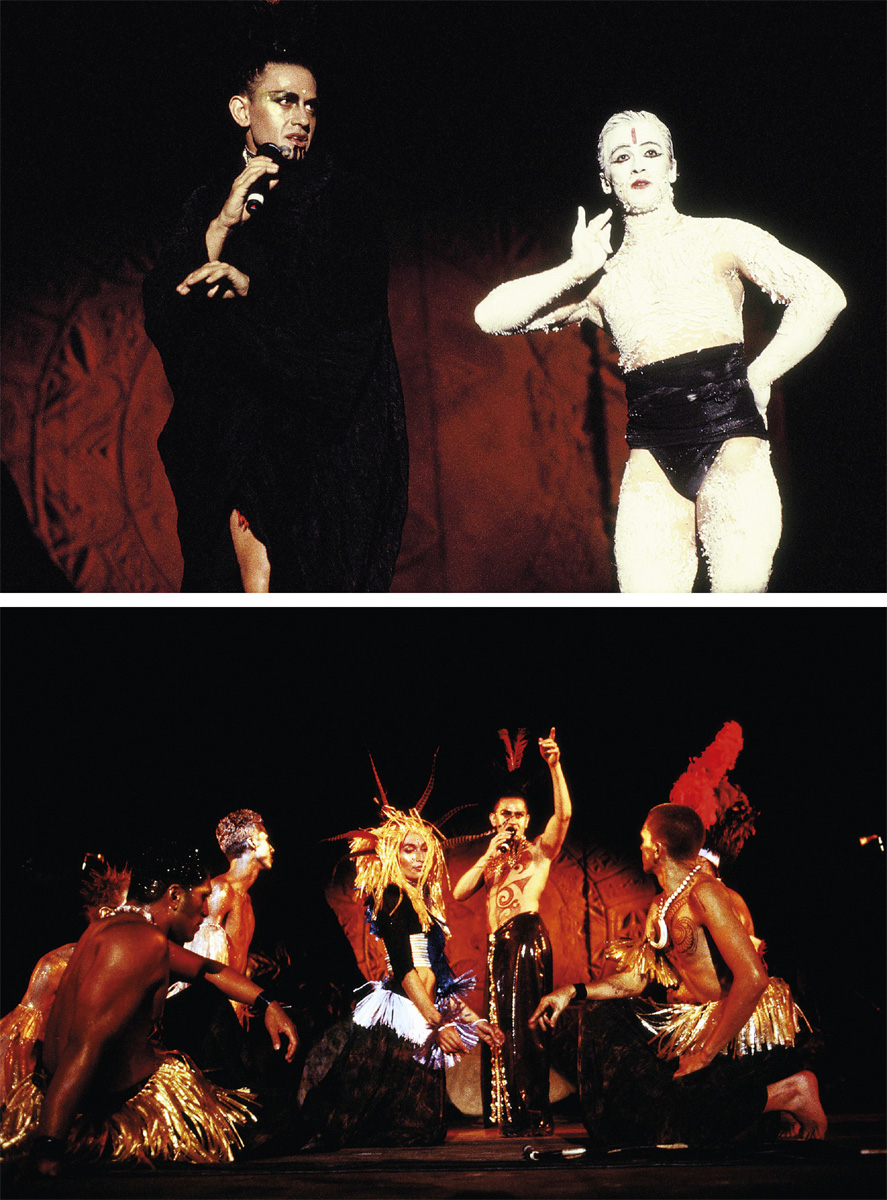

The Starfish Enterprise Cabaret, produced by Nicholas Alexander, 1997. Taane Mete, Mika and Taiaroa Royal performing as Mika and the UhuRas, Konisha and Cassandra. Photo by Nicholas Alexander. Taane and Taiaroa now head Okareka Dance Company.

Mika & The UhuRas, Edinburgh Assembly Rooms, 1997. Photos by Nicholas Alexander. The UhuRas were named in honour of the Star Trek character Lt. Uhura, played by Nichelle Nichols, whom Mika met much later, in 2016.

In Hamilton’s view, Mika’s native drag performances in Edinburgh were successful for the way the signs of the ‘savage’ were mitigated by signs of the ‘safe’, as in one of Mika’s favourite lines: ‘We Māori like to eat you up, but in a nice way.’ Faux foreignness – the grass skirts and painted faces, waiata and haka – was mixed with familiarity: sequins and fluffy hair, pop tunes and disco steps. Seen this way, one might say that Mika’s performances charm audiences – especially those in such festival contexts – by playing up the threat while downplaying the danger. The scary savage is turned queer as: hypermasculine, yes, but with a feminine twist. Of course, it is just as likely that Mika can be seen to be savaging the queer in ways that are especially pertinent, perhaps, in the age of AIDS: the savagery of his performances confirming the terror of the gay man, his sexuality and the body so like and yet dangerously unlike that of the ostensibly straight audience. Was the wild success of Mika and the UhuRas, then, down to the entertaining ways their performances wafted through clichés or to the wily charm with which they confronted audiences with their own prejudices? Were they making nice, or using nice to get at something harder and deeper?

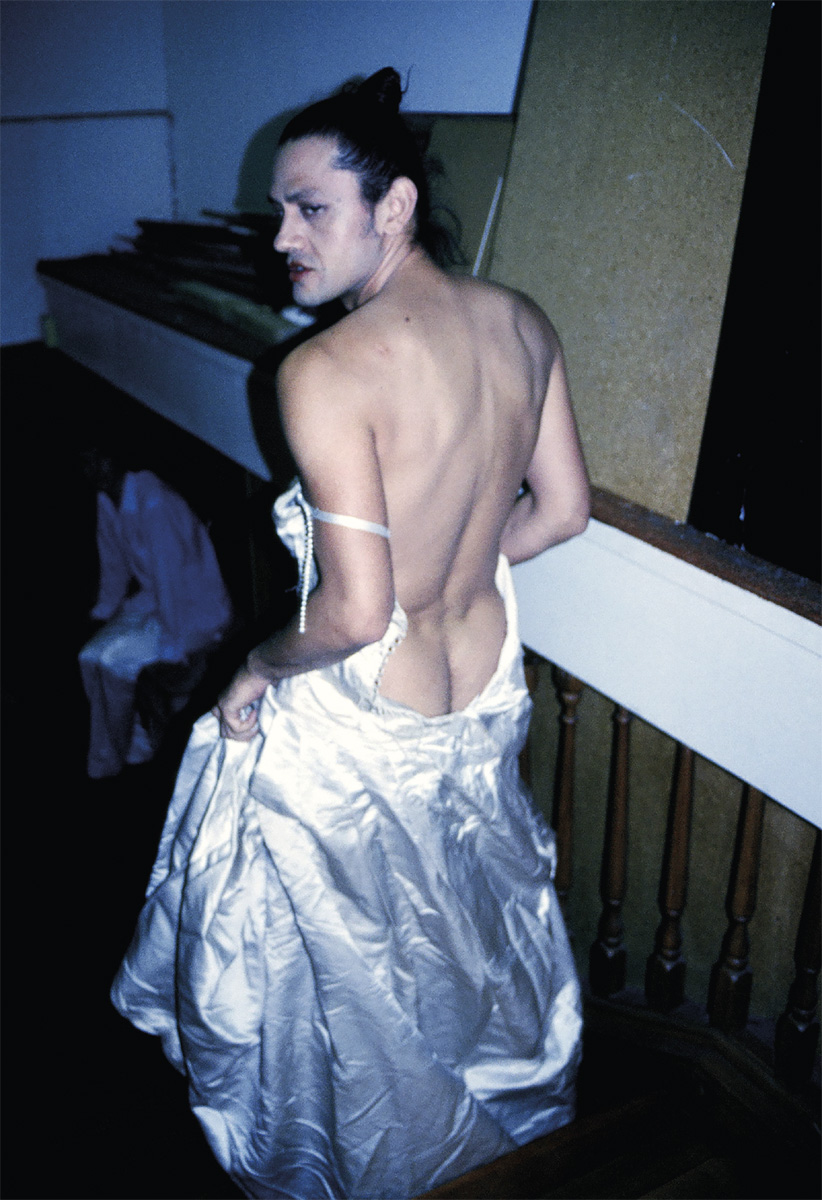

KIWIS ARE NOT THE ONLY FRUIT

In the popular press, reviewers seem to have scrambled over each other to produce prose as wildly superlative and purple as the show. Sue Wilson, writing in the Scotsman, begins by calling Mika a ‘[w]ickedly tacky, fabulously vulgar, disco/drag queen’.2 His costume, Wilson says, is a ‘glittery flared catsuit’ that leaves him flashing ‘a generous expanse of rear cleavage’, and his performance is a ‘raunchy karaoke cabaret’ and a ‘heady late-night cocktail of froth, glamour and sleaze’ that is ‘irresistible’ and ‘exuberant’, ‘darting between preening camp glamour and Fosters Man oafishness’. In the handwritten script for her Radio Forth FM broadcast, Emma Jolliff (now a Wellington journalist) rates the performance a 9½. Sounding more like a shill than a critic, she calls the show ‘a camped-up cabaret of epic proportions’, ‘a risqué and bottom-baring frolic’, and adds that ‘the undulating dancers in drag are mesmerising with their sensual suggestion, and flexibility that makes your eyes water!’3

Meanwhile, under a banner proclaiming that ‘kiwis are not the only fruit’,4 Louise Levene’s extended profile of Mika for the Independent is less over-the-top.5 On the one hand, she notes the enthusiasm of those around her: ‘half the audience has been there before. I’m sat next to a slightly tipsy group of well-ripened Scottish ladies who are already talking about coming again tomorrow. It’s that kind of show.’ On the other, she’s surprisingly critical of the way he ticks the identity boxes – ‘He has special qualities: he’s a Maori (Hello, British Council) and he’s gay (Hello, Arts Council)’ – and of what she views as the sentimentality of his tribute to those who have died of AIDS. In fact, Levene’s tone throughout the interview is one of amused condescension. She translates Mika’s haka for her readers (‘Here is my penis, erect like a spear’), circumscribes his conceits, and closes with scepticism, doubting that his performance would be so successful without his backup dancers. Who needs to perform the cultural cringe when such journalists can do it for you, one wonders.

With Lady Bunny at the Summer Rites gay festival, London, 1997.

Mika and Taiaroa Royal share a cheeky moment at the Perth Festival of the Arts, 1998.

For his part, Mika lists the stars who came to see them: John Hurt, Mark Morris, Lenny Henry, Richard Wilson . . . He says that Prince Rainier of Monaco invited him to perform on his royal yacht, but for some reason he couldn’t do the gig. When the Honourable Tuariki Delamere MP came backstage, Mika took the opportunity to persuade him to take steps to create national funding for Māori performance. Mika still marvels at the success of his show: ‘To be sold out at Edinburgh, being someone from New Zealand, was something of a miracle. Unlike Flight of the Conchords (who were a hit in Edinburgh in 2002) I didn’t get a USA sitcom, but I did get some amazing bookings.’ The show closed on a high on 30 August 1997. When Princess Diana died the following night, they mourned alongside everyone else. And then they carried on: ‘I came back from Edinburgh and went straight to Timaru to do Rocky Horror Picture Show. I was everywhere, did almost everything, but really, didn’t know what to do.’

Mika performing with another UhuRa, Mohi Thompson (below) and with Taiaroa Royal in costumes by Nix (TYT) (opposite), in Tutu at the Auckland Comedy Festival, 1995. Photos and ‘Waharoa’ backdrop by Fryderyk Kublikowski.

Mika with Brian Hartley at the London Fetish Rubber Ball for Skin Two magazine, 1999. His costume is by Connie Fairburn, who was the designer and milliner for Tribal Hollywood.

ANGELS AND ARTISTS

What Mika wanted was artistic control over his work and image, what he was beginning to identify explicitly as his ‘brand’. He turned away from Nicholas Alexander, whose creative management had been so critical to Mika’s success at home and overseas, explaining it this way: ‘I don’t think either of us thought of it as a bad split, just we both wanted different things. He wanted to pursue art, I needed to pursue arts business.’ For his part, looking back on that heady time, Alexander says now that ‘it was not merely a performance but a life’. He goes on: ‘Entertaining people was only part of it. A sheer escape into a land where the quest for identity was subsumed by the surreal woven with dance. And then something extremely sudden, silly, funny or extreme would run across the stage.’

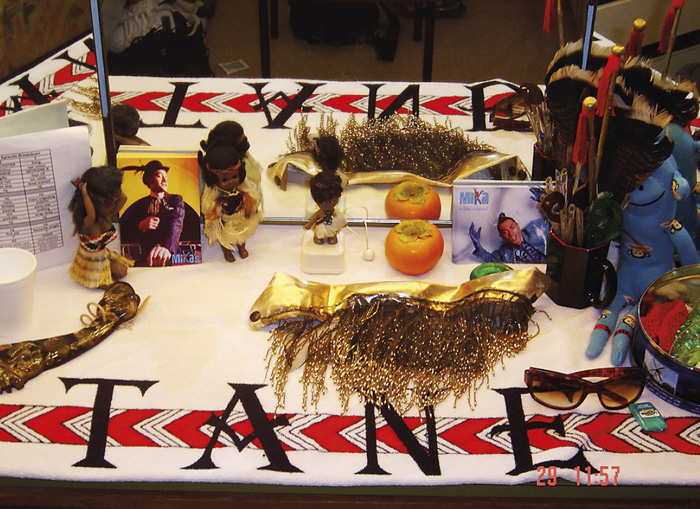

Mika’s Tribal Hollywood dressing-room table at the Queen’s Theatre in Belfast, 1998.

Performing in Tribal Hollywood for the Perth Festival of the Arts, 2001. Mika is in a leather corset by DeeZaStar.

There’s a pleasure peculiar to collaboration, especially in the early period, when everyone is caught up in the fabulousness of finding out what they can do together differently than what they have been doing apart, when ‘what if we . . .’ is immediately met with ‘well, let’s do’. The stronger the artistic personalities, the greater the jolts of creative discovery, but the energy is not necessarily sustainable long-term. Collaborators grow restless. They get cranky. The trajectory of invention begins to feel like inertia, and the tension between individual and collective visions tends to escalate over time. It is extraordinary if, after the whirlwinds of making, promoting and presenting wear off, the collaborators can find reason to carry on or at least remain happily in touch.

Mama Tere, Billy Farnell, Mika and Carmen at Carmen’s birthday party, 1998.

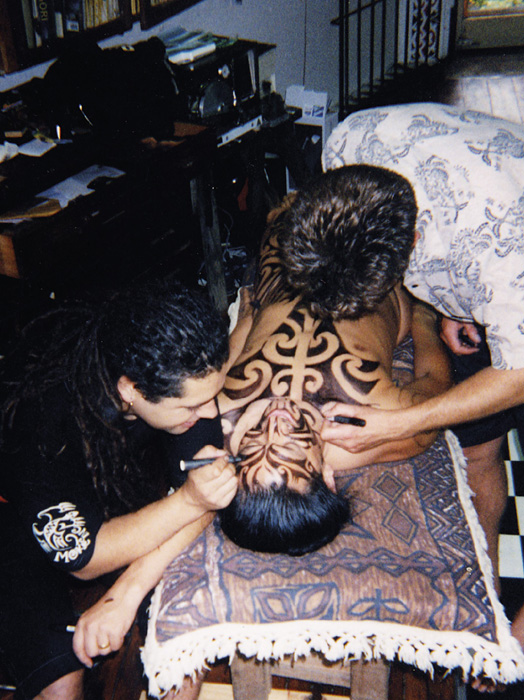

Mika being prepped for the Taniwha music video shoot, 1999. The moko artist is Inia Taylor.

Alexander’s memories of Mika are fond: ‘If it was hard to pin you down, it was because you were always changing – it was about the only constant thing about you.’ In response, Mika says: ‘Every step of the way I’ve been helped by “angels” – always looked after. Artists can’t survive without angels, people who believe in your dream and help you make it happen.’ An artist. Somehow that’s not the first word that burbles to the surface when describing Mika. Performer, entertainer, singer and dancer . . . a quintessential showman, a theatrical hustler and a burlesque entrepreneur, more mountebank than actor, promoting his brand. In doing so, though, he has created an art form for himself – one that challenges the distinction between high art, low art, and no art.

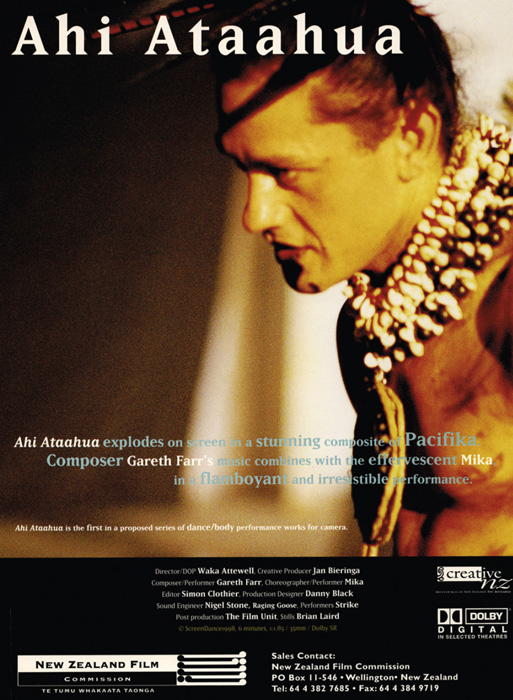

From the Ahi Ataahua film, directed by Waka Attewell, 1998. Costumes by Pacific Sisters.

BEAUTIFUL FIRE

Soon after his return to New Zealand, Mika pulled together a new production team. He and Gareth Farr began creating original songs in English and te reo to present at Edinburgh in 1998 for a new show: Ahi Ataahua (Beautiful fire). By the time they began working together, Farr was already well-known as a New Zealand composer and performer, collaborating with orchestras and chamber groups, and also with theatre companies – notably in the early years of Taki Rua, including creating a score for Hone Kouka’s Ngā Tāngata Toa (The warrior people, 1994) – and for his drag performances as Lilith LaCroix.6 Like Mika, Farr seems always to have been at the heart of what’s hot, his arc of action and discovery intersecting those of other artists who are now well-known in New Zealand and beyond.

Mika with Gareth Farr during the making of Ahi Ataahua in 1998. Photo by Nicholas Alexander.

As a film, directed by Warrick ‘Waka’ Attewell in 1998, Ahi Ataahua is stunningly beautiful, one of the many taonga on the NZ On Screen website. Farr performs with his percussion group, Strike. They’ve been costumed by Suzanne Tamaki, a founding member of the Pacific Sisters, a collective of performance artists that another founding member, Rosanna Raymond, describes as ‘a Polynesian version of Andy Warhol’s Factory: artists, designers, fashion, street, people’;7 this is the aesthetic that we see in the film. The percussionists wear black tee-shirts and long black, patterned skirts. Mika is crowned with feathers, adorned with seashells but otherwise bare-chested, girded in a loincloth with a long, long train made of videotapes, and platform boots. His moves appear effortless, but the videotapes in the cape, Mika says, ‘cut my body to slashes’. Lightly made up, his long hair flying, Farr appears intensely focused on the sounds, the other percussionists and the camera. Mika begins his performance in mōteatea (lament, or traditional chant) mode, in close-up daring the camera to collapse the distance, and in longer shots pulling himself across the moody blue set through the beat, body arching and tongue occasionally flicking.

The performance is poised between burlesque and high art in a way that threatens to dissolve such distinctions. For the first half of the six-minute film, Mika’s movements are slow curves, absolutely controlled, perfectly disciplined, contained – aside from a blinking moment of pure camp, when he yanks his train up to his shoulders, first one arm, then the other, with a quick wink to the camera. The chant turns to haka, the beats accelerate, and everyone lets loose(r). Mika disappears, then reappears on stilts, painted moko, long red plastic grass skirt, surrounded by the musicians, as they move towards the climax. In some shots, water pours on him and then on the musicians, so that the whole experience is immersively otherworldly. They are, Mika and Farr, captured here some twenty years ago, impossibly beautiful.

Mika with members of the Pacific Sisters at the Splore Festival, at Auckland’s Tapapakanga Regional Park, early 2000s.

Photo shoot for Mika and Jan Hellriegel’s New Zealand tour, 1996–97. Jan now runs Songbroker and is Mika’s publisher: ‘It’s how the world aggregates connected souls,’ he says. Photo by Nicholas Alexander.

The stage show developed for the 1998 Edinburgh Festival Fringe and also presented as Ahi Ataahua was not quite that. Mika wanted to make art, he says, because ‘I believed that arts festivals were about art. I was wrong.’ The show surfaced first in Wellington, at the Dans Paleis where, Mika notes, Marlene Dietrich once performed. Jane Bowron’s brief review for the Dominion is cheerily bemused. She describes Mika in ‘a snug-fitting gold romper suit with towering black elevator boots that Elton John would die for . . . doing, at one stage, the most frighteningly accurate impersonation of a tuatara’.8 She goes on: ‘Mika has no shame about grabbing anything he can from Maori culture, swirling pois under the strobe lights, donning a cloak and turning his act into a glorified 90s version of a Howard Morrison show.’ Looking ahead to his world tour, she declares that the show will draw expats ‘as it is soaked in Aotearoa and sure to bring a nostalgic tear to the eye’.

Mika in another frock during a lunch break, 1998. Photo by Nicholas Alexander.

By the time it reached Edinburgh later that year, it’s clear that Ahi Ataahua wasn’t what audiences were expecting after seeing Mika with the UhuRas the year before. In ‘Home on the Raunch’, interviewer Mary Brennan observes that

those who had seen – or possibly just heard about – last year’s tongue-in-cheek cabaret extravaganza where the dancing Uhu[R]as dripped camply with rhinestones and innuendo and Mika himself shimmied, oh so teasingly, between Diana Ross and Lionel Ritchie . . . and then came on, rampant and feisty, in a series of pulsating Maori war chants . . . those people were somewhat nonplussed – okay, in some instances, disappointed – to find the more outré drag-artiste trappings had, along with the Uhuras, been left behind in New Zealand.9

The 1998 show was more ‘reflective’, she says, of Mika’s attachment to Māori culture; more ‘music’, less ‘cabaret’ per se. Mika’s response is recorded by Brennan:

Not one reviewer has talked about my cute butt this time! Or my cute girliness. They’ve talked about the material. And they liked it – or they didn’t like it. And this is what I wanted. I’m not bothered by people not liking the material. Some people like cafe latte, some people prefer herbal tea. You accept it. But what would bother me is not growing, not developing as an artist. Getting stuck – or being looked on as the darling and so gorgeous, but really being seen as one of the freaks of the Festival – would bother me. That’s why I did this show.10

Photo shoot with Greg Semu, part of a larger series, c. 1997–98.

Drag and camp, he proclaims, are passé. That the UK is still clamouring to see him in glitter and feathers just shows that audiences there are not so cosmopolitan as in Auckland. He’s not totally banned the fun stuff, but he doesn’t want to be predictable. Sometimes the only way to change up is to dress down – if an Issey Miyake outfit can be considered that.

STONEWALL AT THE ROYAL ALBERT HALL

Ahi Ataahua marks the beginning also of Mika’s close collaboration with Mark James Hamilton, whose own performance specialty was – oddly enough for a white male Brit – Bharatanatyam, Indian classical dance. Over the next six years, Mika and Hamilton worked together to create a number of memorable shows, including The Angel Tour, Tribal Hollywood, Mika Haka and Rawaka. They also made two successful television series for Māori TV: Mika Live and Te Mika Show. Their first big gig, however, was for the Stonewall Equality Show at the Royal Albert Hall, alongside a cavalcade of stars, including Imelda Staunton & Her Big Band, Elton John, George Michael, Ronan Keating, Julian Clary, Neil Morrissey, and the Harlem Gospel Singers.11 His visibility in New Zealand spiked further when the film that Maramena Roderick (then a foreign correspondent for TVNZ) made of the Stonewall benefit aired at home: ‘That’s when the media around me changed, especially in New Zealand. We were still fringe, but no longer invisible – no longer treated by so many New Zealanders like a dirty secret. Didn’t have money for a coffee the next day, but we were in.’ Not that there weren’t sceptics still, and condescension towards the small-town boy claiming success on the world stage. Mika recalls being asked by Kim Hill on National Radio, ‘[I]sn’t there a problem with being just a flash in the pan?’ His response: ‘Better to be a flash in the pan, than never to have been a flash.’

MILLENNIAL FEVER

Like Merata Mita before her, Maramena Roderick did more than point a camera at Mika. She offered him a home away from home: ‘She said: “if ever you need a bed call me”. Several months down the line, I’m in an ugly bedsit thinking “what am I doing here?” So I called her. I stayed with Maramena for the rest of my time to-ing and fro-ing between gigs and NZ.’ It was the end of the 1990s, the end of the century. The internet shrank the world, brought us infinitely closer to each other on a daily basis, and then threatened to shut us all down with the Y2K scare, a crisis that proved to be as virtual as the connections on which we had come to depend. Air travel was easier, faster, more accessible. Mika was in constant motion, living between England and New Zealand, performing in the East London Mela on the one side, then the Love Parade for British DJ Judge Jules, as his song made the top ten of Top of the Pops, and then back to London and on to the Edinburgh Festival, again. At home, his National Radio programme, Mika and Friends, produced by Gemma Gracewood, was ‘hugely successful’, he says, ‘playing over and over’. He continued to collaborate also with Gareth Farr, making two music video films with Kerry Brown. At the same time, he was also doing the London Fetish Ball, then flying back to Auckland for one of Julian Cook’s legendary dance parties, before going on to the Christchurch Arts Festival where he performed a cabaret titled, simply, Mika. He was still doing Hero Parties, and also the Big Day Out, going to London and Edinburgh, Paris and Glasgow, ‘doing music, cabaret, comedy . . . but not drag’, he says. In this, he seems to be drawing an oddly ambivalent, even disrespectful line between himself and the drag queens with whom he often appears. Perhaps it’s simpler. He isn’t so much standing against playing dress-up as he is pointing beyond conventional ideas of ‘drag’ towards the sorts of gender-bending and gender fluidity we now see widely on stage, on large and small screens, and in everyday life.

Maramena Roderick and Mika in London, 1999. In addition to giving him a home away from home, Maramena filmed Mika’s Stonewall Equality performance for the Paul Holmes show. Photo by Mark James Hamilton.

Poster for Tribal Hollywood, directed by Mark James Hamilton, 1999. The image was initially made for a Witi Ihimaera book titled Where’s Waari, but Mika and Mark liked it so much they used it for the show as well. Photo by Sara Orme.

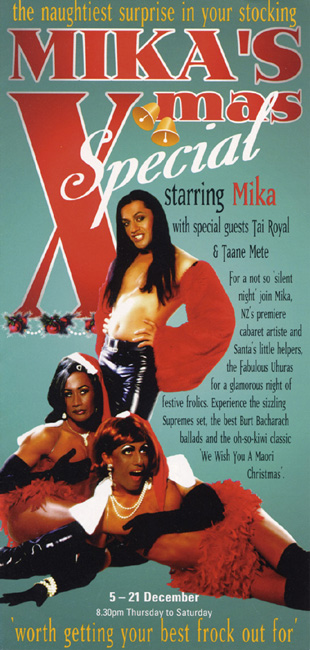

Mika’s Xmas Special, with the UhuRas at the Aotea Centre, Auckland, 1996. Produced by Nicholas Alexander, poster by Arjan Hoeflak.

Pure Mika poster, 1998, designed by Arjan Hoeflak, announcing Mika’s final cabaret performance in New Zealand before travelling to Edinburgh. The show was produced by Nicholas Alexander.

Poster for Ahi Ataahua, 1998. Photo by Nicholas Alexander, costume by Pacific Sisters.

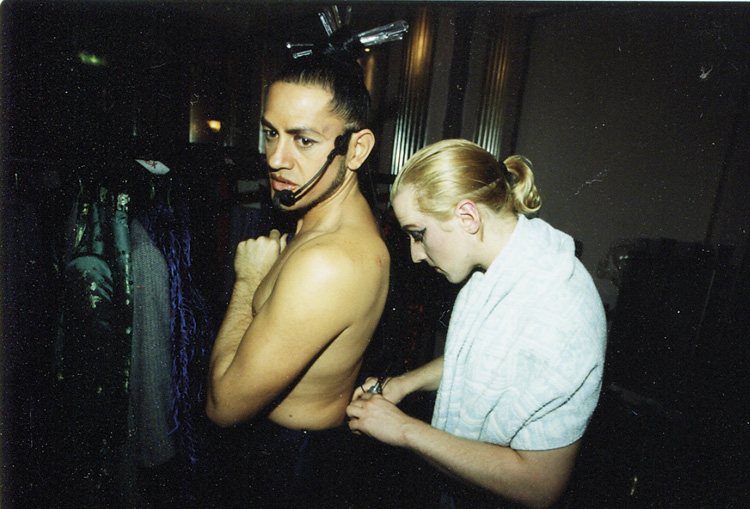

Mark James Hamilton doing up Mika’s costume at the Regent’s Park open-air theatre, London, 1999. Mika shared the bill with Hinewehi Mohi and Dame Barbara Windsor.

Rather like Forrest Gump, Mika manages to be where the action is, often standing next to the spotlight when he’s not in it himself. In September 1999, he had finished The Angel Tour and landed in Liverpool with Hinewehi Mohi just as the drama erupted over her singing the national anthem in Māori.12

I was so glad to be there. Singing the national anthem must have cost her, but what it did for New Zealand will last forever. I remember reciting the Christine Webster story of when Christine was being hated on by the media and politicians about her exhibit. I dragged her out from where she was hiding in her bedroom and said, ‘Get on the phone and answer all those queries now – this is your moment, every artist kills for that moment.’

He counts himself lucky to have been in such rooms, admiring and identifying with Webster and Mohi as ‘two artists who changed perceptions and the way we think about ourselves’. For Mika, both are ‘amazing women who woke us up from complacency in the same way that Carmen Rupe did with LGBT rights’.

As the world turned over into the 2000s, Mika was working hard at whatever was offered, enjoying his celebrity and capitalising on every opportunity that came his way. He’d moved a bit beyond DIY touring, and still remembers the thrill of being flown from England back to New Zealand for the first time. But at the same time,

[i]t was beginning to occur to me that the only way I was going to have this thing they call popular fame was to start doing shopping mall appearances like S Club 7, and that was not for me. On one level, I was perceived as a native drag creature, on the other I was performing at festivals and the Royal Albert Hall, so I had to change my tack.

Mika getting ready for his next production number with Mark James Hamilton, backstage at the live version of Te Mika Show. The show had 24 large-scale song-and-dance numbers, with stars from Tina Cross and Jackie Clarke to Nesian Mystik, Adeaze and Georgina Beyer. Costumes were by Pollyfilla (Colin McLean), who created over 250 costume changes. Photo by Pollyfilla.

Performing at the Sweetwaters Festival, 1999. Top, Mark James Hamilton performing Bharatanatyam as Mika sings ‘E Taku Hoa’ (written by Mika and Gareth Farr). Bottom, left to right, Ueta, Taiaroa Royal (obscured), Yolan Moodley, Rietta Austin, Mika, Niwhai Tupaea (obscured) and Barney. Photos by Kerry Brown.

Doing Julian Cook’s gay nightclub dance party and the Christchurch Arts Festival in the same week made him feel like ‘a star in my own country’.

Kerry Brown worked with me on two short films – Angel and Taniwha in New Zealand – and then we met up in London where he put me in Judge Jules’s Top of the Pops music video, ‘It’s My Turn’, which was seen by the little Scottish girls and boys I was teaching the haka to. So one minute I’m in Tottenham Court Road without any money, next I’m in Craigmillar, Edinburgh, teaching kids in public housing to do the haka, travelling back to London to make music videos and performing Tribal Hollywood in Liverpool and Christchurch.

The travelling, and the quick-change artistry required of him in performing his diverse shows in vastly different venues from one night to the next, made him feel that his career was taking on a life of its own, out of his control. He had plenty of ‘angels’, friends like Richard O’Brien of Rocky Horror fame, who showed him the ins and outs of London’s celebrity circuit. Vicky Blood (Steps) and the actor David Soul (Starsky & Hutch) also looked out for him whenever he was in their neighbourhoods – perhaps, he says, ‘because I am so brutally honest about being gay, over-the-top and a tribal from the South Seas – in other words I wasn’t competition for any of them’. But somehow the work was becoming, again, alienating.

One day, I was doing a show at the Neptune Theatre in Liverpool. It was a great show. I enjoyed it. But then, at the end of the show, sitting around again with people I didn’t know, again, who were drinking and smoking, again, waking and not knowing quite where I was, again, about to get on another taxi to another train station to another destination, again . . . I went ‘nah’. And anyone who knows me, knows that when I go, ‘uh, nah’ I mean it.

AHI ATAAHUA

A new century. Time for another artistic makeover. He came home to New Zealand and, with Mark James Hamilton, pulled together a new group of young aspirants, trained them up and launched them on stage and on television as Torotoro. They mixed and matched, new material and old, most successfully perhaps with Tribal Hollywood, which toured the world, including fringe festivals in Melbourne and Edinburgh. In 2001, they reworked Ahi Ataahua as a showcase for Torotoro. We see them in the music video directed by well-known Māori-Pasifika producer-director Whetu Fala and Sharon Hawke.13 The contrast between this version and the 1998 short film could not be more striking. Mika is standing on the beach, wearing loose-fitting orange exercise pants with a black waistband. He has a moko painted on his chest and feathers and a carved bone comb in his hair, which has been tightly bound into two plaits. The camera zooms in to him as he sings ‘Ahi ataahua, ahi ataahua’, overlapping himself in an obviously mixed loop. There are drums, but the music is more pop, and electronic, than percussive. We move from close-up to a high long shot of the company, ten men and women, dancing on the beach. Their costumes are, in essence, the inverse of his: black trackpants with white stripes on the outer seams and orange waistbands, the men topless, the women in black-and-white sports bras. They are also moko’d – although one cannot tell paint from ink in the video – with feathers, and jade or bone pendants and combs for accessories. They spread out behind him, surging forward, their feet skimming rather than stomping on the soft sand as their hands wiri (tremble). Mika is almost, but not quite, submerged in the group as he leads them, singing:

Ahi ataahua

Mai taku hā kotahi nau hā i te rā tuatahi

He tāne aroha tāngata ahau

He tāne me te taha wahine

Tāne kaha au me ahau a ka tāne ia

Tāne kaha au me ahau he pono te kaha

Tāne kaha au me ahau he tangata

He rangatira.14

Mika in make-up for the Ahi Ataahua video shoot, 2000. The moko artist is Te Rangikaihoro Laurie Nicholas.

Ahi Ataahua, 2000. Green-screen shot from the music/dance film by Whetu Fala and Sharon Hawke.

Filming Ahi Ataahua, 2000.

Mika’s movements are rounded, the fierceness cushioned and controlled as he, and they, move up the dune and over towards the camera.

This haka is gentle, lyrical, halfway to some-indefinable-thing else.15 It could be aerobics, or jazz, or ballet, but as the camera shifts again to hold Mika in its frame, we see that his dance has been inflected with the shapes and rhythms of Bharatanatyam. Arms waving, legs arcing and angling, the company follows him, like the Pied Piper, in a line across the ridge of the dune. Another chorus of ‘ahi ataahua’ and Mika is seen in a korowai (cloak), the surf crashing behind him: a rangatira, chieftain. His song has become an anthem, an expression of faith and foresight. In the bridge between choruses, the company performs a more recognisable haka as the camera cuts to and from shots of Rangi Rangitukunoa and Kereama Te Ua, dancing with taiaha (staff-like weapons) mid-stream in the bush. They shift between haka and Bharatanatyam, sharp elbows and knees mixing with curving mudras. The video culminates with the kids leaping and sliding in the sand over the ridge, as Mika stands firm in their midst, his arms outstretched. Then they shimmy in a line at the edge of the water, swaying their hips with their arms over their heads, looking for a moment like I Dream of Jeannie, as Mika sings again ‘ahi ataahua, ahi ataahua’.

I’m not lazy, I’m very focused, but performance for me has never been just a gig.

— Mika

Mika wears a jacket of cardboard and glitter from World, 1996. The jacket is now in Te Papa Tongarewa. Photo by Arjan Hoeflak, make-up by Stefan Knight.