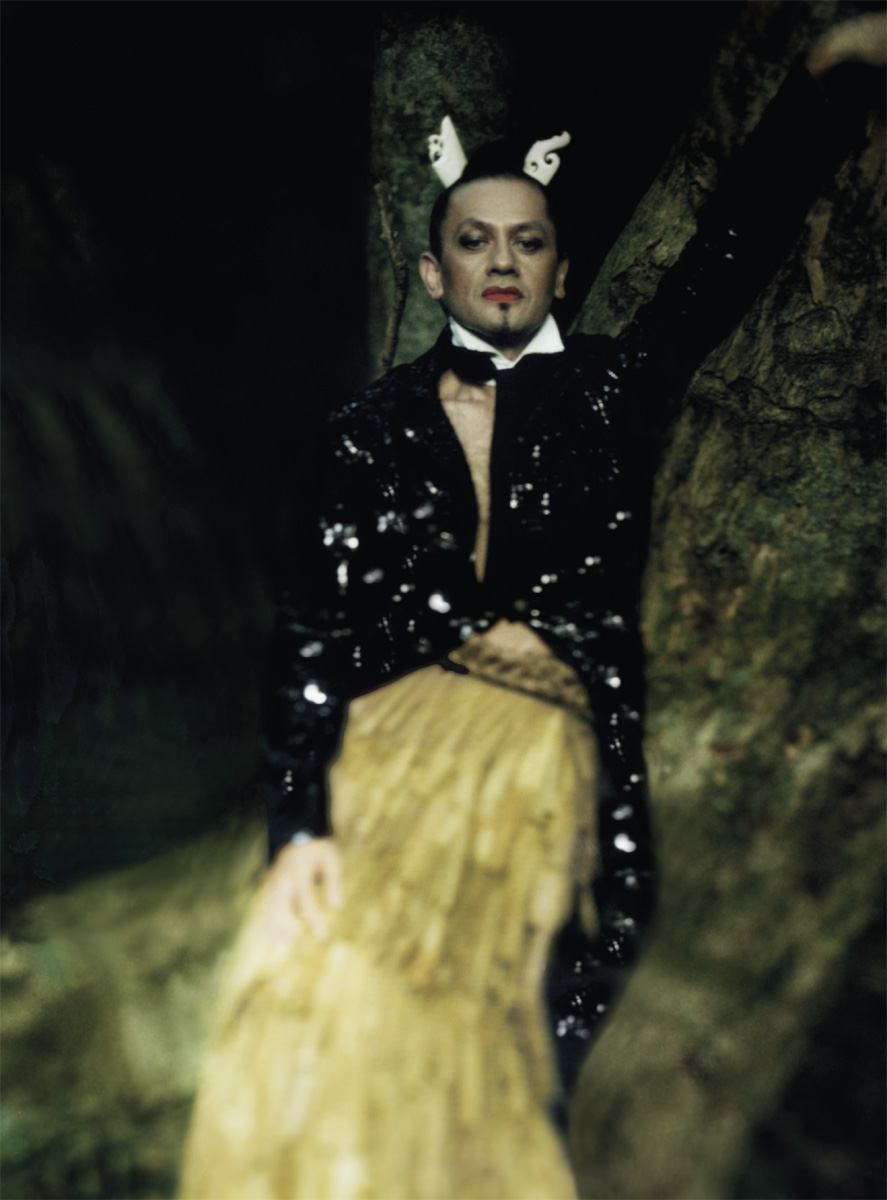

From Sara Orme’s Barbie Aotearoa exhibit, COCA, Christchurch, 2004. Mika is ‘Māori Barbie’. Black sequinned tailcoat by Elizabeth Whiting, grass skirt by Fifa Banze (Pacific Sisters).

CHAPTER SEVEN

PLASTIC MĀORI

And then you have people like Mika, [who has] trained in traditional dance, adapted it to cabaret, done very well, and is now back here trying to create a New Zealand equivalent of Riverdance, working with a group of mainly young Māori and Pacific Islanders to create an authentic New Zealand Polynesian-Māori dance theatre experience. And I think he’ll succeed.

— Helen Clark

At the time it seemed terribly radical. It doesn’t seem so now.

— Mika

WORLD FAMOUS . . . EVEN IN NEW ZEALAND

By the turn of the millennium Mika had become ‘world famous, and not just in New Zealand’. The phrase is a variation on a New Zealand commonplace, ‘world famous in New Zealand’ – itself the by-product of the L&P marketing campaign of a few years back – and reflects the ambivalences of success in a relatively remote collation of islands.1 In fact, to be famous here, unless some sign of approbation from the wider world is apparent, can often seem like starring in one’s school play: gratifying but brittle, at risk of being shattered by the critical gaze of a ‘real’ audience. The thing about the tall poppy syndrome, in New Zealand as elsewhere, is that it’s at its most invidious when it’s more passive than aggressive. The deafening silence that often envelops performing (and other) artists when they return here after they’ve been rewarded with raucous applause everywhere else can be surprisingly enervating, if not unexpected.

And so it was that, at the end of 2000, as before, Mika soared back to New Zealand carrying a portfolio of largely laudatory press coverage and new contacts, many of them celebrities and promoters eager for his next show. He was broke, again, and, in spite of his overseas successes, he again found himself having to start from scratch on his own terms. With Mark James Hamilton, he founded Torotoro, a dance company featuring ten young Māori performers, and launched Mika Haka on 8 February 2001. He says, ‘we managed to go from nothing to something’. Their enterprise was underwritten in large part by the then Labour government:

I’d had other dance companies, but Torotoro was the first time I’d been able to pay regular wages, with support from Prime Minister Helen Clark. She had decided to take a tour of Māori groups, came to my studio and watched us work, and after that invited me onto the board of Creative New Zealand.

This was a significant shift in government funding of the arts, which still tends to privilege the already privileged.

During the years of Helen Clark’s leadership (1999–2008), New Zealand turned its face to the world, becoming more diverse by absorbing foreign ideas and immigrants and, at the same time, becoming both brand and destination, if not so ‘100% Pure’ as the long-running tourist advertising campaign claimed. Carlyon and Morrow tell us that

New Zealand in its early twenty-first-century incarnation bears little resemblance to its post-war, statist, conservative, proudly monocultural self. Now one of the most deregulated free-market economies in the world, it is also one of the most multicultural and most ‘globalised’. (415)

Neoliberalism, as practised by Labour during Clark’s long reign, created a country that has become at once more fluid in its economies of arts and cultures even as the social fabrics and safety nets of the previous century continue to erode. In Carlyon and Morrow’s words,

Many of the heralded social and economic advances of the late twentieth century – the increasing diversity of New Zealand’s population, the evolution of a dynamic, internationally competitive primary economy, increasing sophistication and declining cultural isolation – stemmed from the pronounced opening up of a previously rather staid and insular nation to global influences, human and capital flows. On the other hand, after 1984 in particular, many New Zealanders were made all too aware of the costs – human, social and economic – of liberalisation. (419–20)

Ironically, as many of the societal constraints – sexism, racism, homophobia – that at best could be said to have inhibited individual fulfilment, and in reality ruined innumerable lives, have been pulled back, at least officially, the actual business of living has become ever more precarious. It is even more ironic, then, that the strategies that Mika deployed in the 1980s and 1990s in rejecting more conventional career paths in theatre, film and TV – his acts of ‘disruptive innovation’ and ‘creative entrepreneurship’ – are now prescribed for aspiring young creatives everywhere. For many people, young and old, being self-fashioning and self-selling is not just about ambition any longer. It’s about survival.

Periodically, Mika has been accused of exploiting the attractions of young people to sustain his own career, and to some degree that is so, and not so unusual. The documentary Mika Haka Kids seems to have been designed, in part, to push back against those casting such aspersions.2 In its opening sequence, Mika notes that ‘some kids don’t get a chance, do they? That’s when I thought, oh my God, it’s not about me at all. It’s not about me.’ Hamilton, as Mika’s co-director during this time, describes a typical exchange between critics and Mika: ‘It’s not very authentic is it? [laughs] And Mika said, “Well, Renee and Nancy were not willing to take their tops off and perform with their breasts out. . . . Oh! You didn’t mean that authentic!”’ The truth is that the creative industries are especially beholden to the energies of eager up-and-comings, apprentices and interns who for little or no pay play small but vital roles, performing as extras or in choruses and doing the hard yards behind the scenes in theatres, studios and galleries worldwide. But the financial and other costs of building and running a small production company – especially of educating new performing artists to work as artists – are generally high enough to dissuade those in it just for vanity’s sake or for prurience.

Below and opposite: Mika performing with Torotoro for Larry Ellison’s Oracle/America’s Cup event at Auckland’s Civic Theatre, 2003.

Creating Torotoro wasn’t just about putting on a flash new show. Both the challenges and the incentives for taking on young people at such a critical stage in their development were (and remain) more substantial, he says: ‘I formed the trust so I could help these kids. I’m a childless gay man. Privileged. I started helping because I could, with the help of others. Thousands have had better lives as a result.’ His rules for success were fiercely realistic: ‘Their diets and their health, the way they lived was so appalling. Kids were having a lot of sex, so there I was “you can’t drink, you can’t smoke, you can’t eat junk food, but here are the condoms”.’ To create Torotoro, Mika and Hamilton took to the streets and malls, talent-spotting young people – ‘what should have been mediocre young people’ – auditioning them and then training them rigorously, enforcing discipline at all levels. They had to be prompt, and they had to learn to work. Te Ara Poutama, the Faculty of Māori and Indigenous Development at Auckland University of Technology, provided the platform. He developed a summer course, taught on the university’s marae, Ngā Wai o Horotiu, and created a charitable trust to underwrite the work. It wasn’t charity in the conventional sense. He expected the kids to walk away savvy, and for the experience to have empowered them in ways that growing up alienated in the Auckland suburbs hadn’t. At the same time, he was turning his individual practice into its own genre of performance:

I was hugely concerned that while there was support for ballet, there wasn’t much for kapa haka or hip hop or any kind of dance form that involved young people, brown people. I wanted to mix breakdancers and kapa haka, and that’s what I got. At the time it seemed terribly radical. It doesn’t seem so now. The fact that I could get Māori boys into shiny green lycra, with furry bits and so on . . .

ALL THE WAY FROM THE HULA HUT IN THE SOUTH PACIFIC, THE ONE, THE ONLY . . . MEEE-KA!

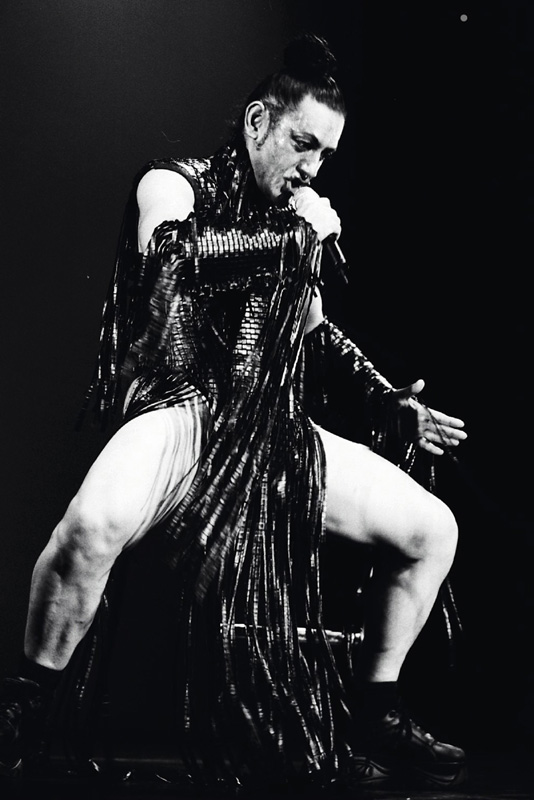

Performing Mika Haka with Torotoro at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in 2003, Mika appears at the centre of a swirl of young dancers, his ‘very own Polynesian dance crew’. He sings: ‘Tonight’s the night, the night of stars, auē ko te pō, te pō nei’.3 The music is electronic piano and drums, cabaret meets circus meets nightclub, with a bit of Looney Tunes thrown in for good measure: ‘Polywood’, he calls it. The costumes are equal parts slick and grab-bag. The company wears black lycra briefs, fringed like abbreviated distillations of the plastic hula skirts in old Hollywood films and topped with bright white shirts that are cropped in various ways. For his part, Mika is wearing a long grass skirt over bare legs, a black sequined swallowtail coat with cut-outs under the arms, a starched white collar that looks like it’s held in place only by a black silk cravat, and a black felt top hat with feathers jutting jauntily upward.

The kids – including Mokoera Te Amo (Te Arawa), Taupuhi Toki (Ngāpuhi), and Kasina Campbell (Ngāpuhi) – swarm frenetically around him, running with knees up, dropping to the floor to slap their thighs, swinging their arms and pointing from themselves to Mika in time with the lines: ‘the one and only . . . Meeee-ka!’ Their dance is a collision of haka, disco, music hall, and hip hop, with aerobics moves tossed into the mix at odd points. They fill the stage, then sweep away, clearing the floor for Mika as he alternately swings poi and high kicks like a Radio City Music Hall Rockette. Between choruses, mixing te reo Māori with te reo Pākehā, he tells the audience: ‘Tonight we invite you to an exotic evening of music and dance . . . We perform for you our forbidden dance from a distant shore, never seen before. It’s Pacific circus time! Step right up! Nau mai, haere mai!’ As the music fades to a few allusive bing-bing-bing-bongs on the electronic piano, the company recedes to the shadows, mist pours from the smoke machines, and Mika takes central stage to greet the audience as MC: ‘Kia ora . . . Good evening. My name is Mika, rhymes with . . . Madonna. And lurking in the wings is my very own Polynesian dance crew, Torotoro. By daylight we walk the earth as patupaiarehe – travelling entertainers.4 But by night, we become . . . taniwha.’ He sticks his tongue out and waggles it with a mixture of seduction and threat, and then pauses for effect. Slapping his thigh in a parody of incipient terror, he goes on: ‘What’s that I hear you scream? Come on, Edinburgh, wakey-wakey! A taniwha in Polynesian legend is a sea monster with a very long . . . tongue!’ Again he waggles his tongue and stares provocatively at the audience, before launching into a lengthy, mystifying speech about the natives of Aotearoa – the land of the long white cloud: ‘We named her Aotearoa . . . that’s right, we named her after fog.’

As Mika and the kids carry on, Mokoera, muscular and dread-locked, breaks out, brandishing a rākau (a club-like weapon). Shouting and grunting, he circles the stage as if performing a wero (challenge) to the audience on behalf of his rangatira, Mika. His performance is as ‘authentic’ as it can be in the burlesque swirl, its form and content somehow true both to marae protocol and touristic entertainments. And so the show goes on, almost in earnest and not quite in jest, simultaneously for real and parodic, a play on the performance of encounter with the native cultures of the South Pacific, always with a sly wink and a bit of a come-on underlying.5

MIKA, MĀORI QUEEN OF SCOTS

Mika Haka is a performance that shouldn’t work. Its peculiar pastiche of Vegas, cabaret, music hall, aerobics, sideshow and kapa haka, as it seems simultaneously to Europeanise and queer the Māori, is infinitely disturbing. Is it a reiteration of colonisation? A feminisation of the macho Māori warrior? As a kind of postcolonial camp spectacular, it speaks to, over, and against spectators, successfully maintaining itself as a hot ticket. At the same time, it may (or may not) surreptitiously undermine the consumerist complacencies of its audience, an audience that is, after all, very used to seeing indigenous performers – Japanese drummers, Chinese martial artists, Vietnamese puppeteers, African dancers and so on – costumed and painted, or stripped to the barest minimum, presenting their ‘traditional’ performing arts at festivals around the world.6

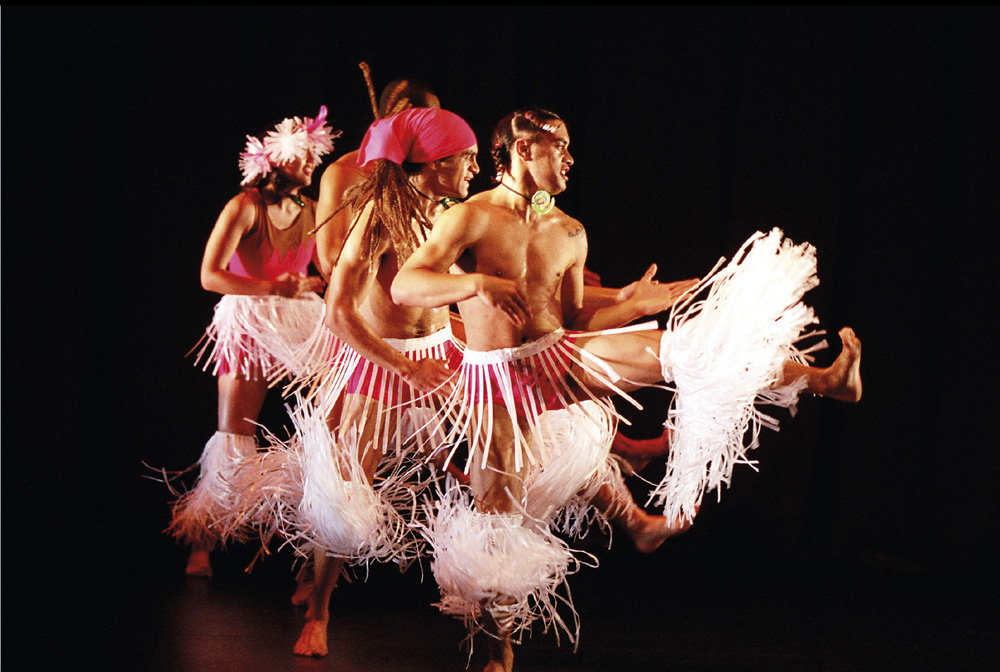

Performing ‘Aotearoa’ with Torotoro Urban Māori Pacific Dance Crew in the Mika Haka Show at the Otago Festival of the Arts, 2003. Costumes by Elizabeth Whiting and Fifa Banze (Pacific Sisters).

Mika’s performances in Edinburgh show us how easy it is to step over the line from native costume to native drag. His grass skirt is nothing like a Māori piupiu: the woven flax skirt worn at traditional ceremonies and cultural performances. It’s expressively, provocatively faux-native, when combined with the sequinned, vented coat (a reflection, perhaps, of the Liza Minnelli impersonators one saw in the eighties). He is heavily made up, not with traditional moko but with darkened eyes, cheeks, and lips that make him look both seductive and scary. His tongue play mimics that of Māori men doing the haka, but its cannibalistic threat carries a different kind of ‘want to eat you up’ message. It’s more an invitation to get down and dirty than a sign of the warrior spirit being channelled and projected onto an opposing combatant.

Performing ‘Juiced’ with Torotoro Urban Māori Pacific Dance Crew in the Mika Haka Show at the Adelaide Cabaret Festival, 2003. Costumes by Elizabeth Whiting and Fifa Banze (Pacific Sisters). Photo by Mick Ivers.

Even his hat is extraordinarily evocative, calling up images from the early days of colonisation, of natives draped in the blankets brought by missionaries, topped off by jaunty top or bowler hats, decorated with feathers and shells, and probably acquired as much through force as by peaceful commerce. Or rather, it calls to mind a cavalcade of images from the movies, from Green Dolphin Street (1947) to The Piano (1993) and beyond. The collar and tie, shiny as they are against his bare skin, also look as though they were scavenged off a dead settler, albeit one who might have taken a turn on a Hollywood soundstage before setting sail for Aotearoa.

Performing ‘Ko Te Iwi’ with Torotoro in the Mika Haka Show at the George Square Theatre in Edinburgh, 2003. Costumes by Elizabeth Whiting and Fifa Banze (Pacific Sisters).

The music starts as an almost original overture that mixes English with te reo Māori. The patter echoes the Māori tourist show – itself a less than savoury performance practice. So do some of the sequences, as when the members of the troupe, dressed as youthful mirrors to Mika, go to the floor to perform in a way that looks like traditional Māori stick games, albeit without the sticks. This morphs into a chorus line that then gives way to Mika demonstrating his skill with the poi, which might historically have been a men’s pursuit, but is currently a female-dominated practice. And while this opening number builds to a hyperbolic version of ‘Tōia Mai’, in the end what we see is Mika kicking like a Rockette. The music is live, but augmented, electronically self-replicating. The lights flash and pulse. The mirror ball spins. In the heavily edited film, Mika’s image splits and multiplies, and then it reintegrates. Sort of.

The mirror ball provides an apt lens for considering Mika’s performance. Unlike Lacan’s mirror stage, the mirror ball’s fragmented surface refuses direct reflection of the subject.7 Instead, it picks up pieces of Mika’s performance and recasts them about as bits of inarticulated light, circling the spotlighted figure of the performer and refracted away from him towards the audience. These bits of light put us, the spectators, in much the same position as the troupe of young Māori dancers who, dressed as fragmentary reflections of the star, orbit him, repeatedly point towards him and, slipping from ‘ME ME ME’ to ‘MEEEKA’, continually call his name. Under the mirror ball, only Mika’s image remains whole, intact. Mika stands in the centre as the one, the only, Mika – simultaneously in native drag and being the real deal. His performance doesn’t so much eclipse the originals he mimics as complicate our vision of them, expose their limitations. His excess implies their lack. Why limit yourself to the dominant definitions of Māori and Pākehā? Why play it straight, he seems to ask, when there are so many delicious options and opportunities for self-invention? What might be seen as a mistaken performance of Māori cultural identity, frozen at the moment of childhood loss, becomes also an affirmation of Mika’s identity as a queerly self-fashioned, essentially Māori man.

This way of looking not only valorises Mika’s victory over early experiences both of homophobia and of colonisation, it also glides past and potentially elides the question of what Mika Haka has to do with kapa haka. In Mika Haka, Mika has it both ways. His performances are fuelled by his hard-won knowledge of language and traditional performing arts, wound around the kinaesthetic tropes of haka, in particular, and featuring performers who, unlike Mika, learned their performance practices with whānau on the marae. The company’s performances of haka appear proficient enough, so that the points of slippage, the intrusions of other types of performance, the sly winks and the abrupt shifts into contrary stances are obviously intentional. What he performs is not quite parody – if we follow Fredric Jameson’s ideas of parody as social critique – but it’s not quite not parody either.8 It calls up, without telling us what to do with, our (Māori and Pākehā alike) submerged assumptions about natives and indigenous performance, the ones imprinted into our collective cultural unconsciousness in spite, or perhaps because, of the liberal niceties of biculturalism in New Zealand (and multiculturalism elsewhere).

Performing ‘Juiced’ with Torotoro in the Mika Haka Show at the Adelaide Cabaret Festival, 2003. Photo by Mick Ivers.

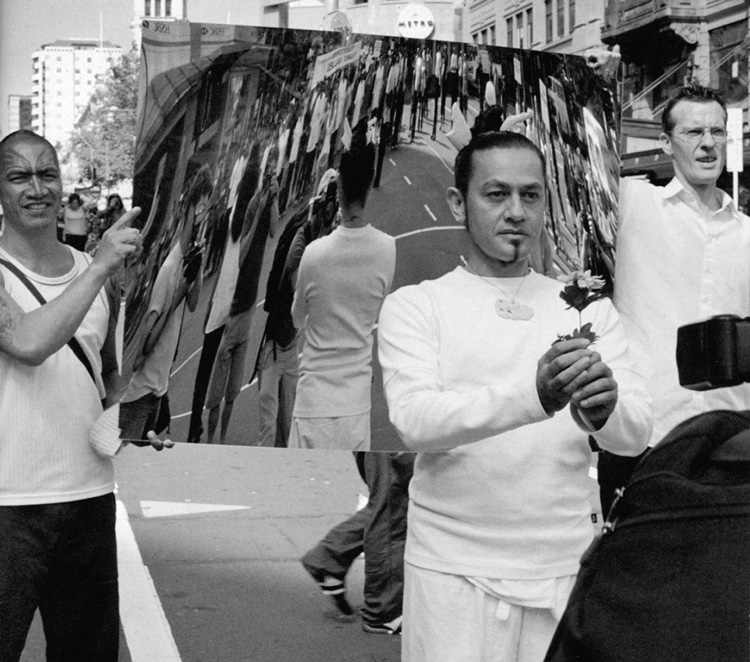

Counter-protesting at the Destiny Church anti-gay march, Wellington, 2005. Photo by Monty Adams. It was Adams’ idea to position the mirror so the marchers could see themselves. Left to right: Taurewa Biddle, Mika, Stephen Gray. Biddle had AIDS and passed away in 2017.

More provocatively still, in detaching signal elements of Māori performing arts from their customary frames – the marae and the kapa haka stage – and slamming them together with odd bits of other dance forms, Mika simultaneously embraces and exposes kapa haka as an invented tradition. In reinventing kapa haka, Mika reveals it as a practice that can be put on and mixed and matched like his costumes, and raises the possibility that what we understand of Māori identity is equivalently put on, mixed and matched. That is, in his minstrelsy, Mika can be seen to make visible – whether for play or for critique, it is not certain – what Alan Filewod, in ‘Modernism and Genocide: Citing Minstrelsy in Postcolonial Agitprop’, calls a ‘longing for a fantasized authenticity’ (163) – minus the genocidal undertones, but no less rapacious.

POLYNESIAN GENES WITH ELECTRIC DREAMS

Mika trades on the traditional throughout his Edinburgh performance. The kids sing waiata and mōteatea, call karanga, brandish patu (clubs) and rākau, perform moves that are taken from the haka, and shout challenges. Following Mokoera, the young men dance with the rākau, as if performing the wero, albeit in ways that go beyond the traditional: extending their legs and leaping in angular ways that simultaneously maintain their connection to the ground and make them appear to float free, ultimately transforming the haka first into a hoopless hula and then into breakdance. Mika reappears, the hat replaced by a straw crown, the swallowtail coat replaced by a flowing, fuzzy red-and-black robe that allows him to expose his chest, singing ‘Polynesian genes with electric dreams’. Calling himself a ‘jetset warrior’, he says, ‘when I was a boy I was told there was no point in learning reo because there was no market for it, and now . . .’ as the company falls into a full haka. It is both beautiful and absurd, especially when the company changes into fluorescent green lycra jumpsuits.

This is camp. Not the ‘disengaged, depoliticized – or at least apolitical camp’ that Susan Sontag claimed in her 1964 essay ‘Notes on Camp’ (54); Mika’s postcolonial camp bears a passing resemblance to the sort of memento mori that Andrew Ross identifies in ‘Uses of Camp’ (1988), for the way that it performs a negotiation with the past from a high perch in the present, rediscovers ‘history’s waste’, and resurrects ‘diseased cultural forms’ (315), although I would like to believe that in calling forth the residue of colonisation and the nostalgia for a pre-colonial native identity as it persists in contemporary New Zealand, Mika’s performances are not so deadly as all that.9 As postcolonial camp, Mika’s performance can be seen to contain ‘an explicit commentary on feats of survival in a world dominated by the taste and interests of those whom it serves’.10 Mika’s postcolonial camp is celebratory but not utopian, political without being prescriptive, and critical without losing its sense of humour.

PLASTIC MĀORI

The ongoing scramble to maintain Torotoro financially led Mika to take up entertainer Suzanne Paul’s invitation, in 2004, to create the featured performance for her tourist venture, Rawaka, in the old Fisherman’s Wharf in Takapuna, Auckland.11 The contract allowed Mika and Mark James Hamilton to employ twelve young Māori men and women and explore a genre of performance that is at best overlooked, and often condemned for its crass commercialism, by all but tourism entrepreneurs and their audiences. Mika’s company was contracted, in essence, to provide an authentic Māori experience in an enterprise that – unlike other such tourist ventures (Tamaki Village, Mitai, Ko Tāne, Te Puia, et al.) – was otherwise owned and operated by Europeans. It was fun while it lasted.

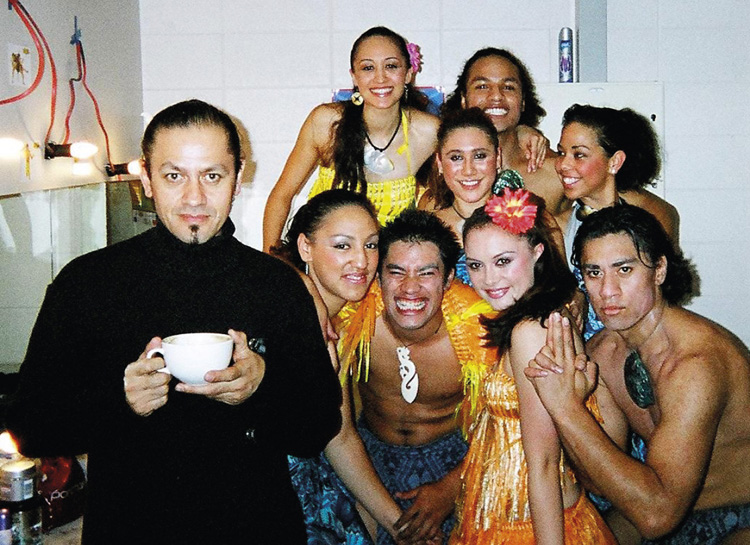

Backstage at Rawaka after a rehearsal. Front row, from left, Mika, Sariah Witika, Mauriora Kingi, Jade Winter, Aukilani (Joey) Paulo. Middle row, Roxanne and Lady Sai‘ifiti. Back row, Kasina Campbell and Robert Gatu.

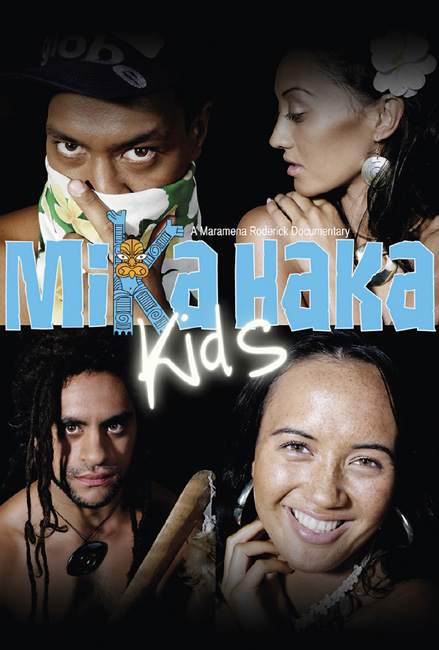

Mika Haka Kids documentary, 2008. Directed by Maramena Roderick, it was a Qantas Best Documentary finalist. From bottom left, Mokoera Te Amo, Taupuhi Toki, Kasina Campbell, Renee Winter. Cover design by Pierre Godquin; photos by Russ Flatt.

The Māori encounter with tourists is generally seen to be performed at the intersection between the ritual and the theatrical: that is, between the elements of pōwhiri and the marae-centred entertainments, especially concert parties, that were traditionally enacted in the meeting between tangata whenua and manuwhiri (visitors), and the traditional performance practices of the early European settlers. From its beginnings in nineteenth-century Rotorua, the shape of the tourist show stabilised fairly quickly as something that mixed entertainment and education, demonstration and participation, and it remained relatively constant throughout most of the twentieth century: welcome, song and dance, invitation to join in, photo-op, dinner and farewell. There is an element of minstrelsy to such shows, the native drag offering a shiny surface that more often than not verges on pastische and parody. It’s not camp per se, although it has elements thereof. Mika calls it ‘Plastic Māori’ – both a reference to the superficiality and changeability of such performances and a way of taking on the sort of slander that is sometimes thrown at people who seem to be putting on a Māori appearance without the requisite knowledge or commitment to culture. When Torotoro disbanded, he called the trio that remained Plastic Māori and performed with them for a time.

Plastic Māori perform the Divine classic ‘You Think You’re a Man, But You’re Only a Boy’ (opposite) and ‘Brown Girl in the Ring’ by Boney M (above). In both photos, from left to right: Mokoera Te Amo (bass), Mika, Taupuhi Toki (drums), Kingi Tuutaniwha (musical director). The videos were shot at the Transmission Room on Queen Street, Auckland, 2006. Costumes are by Pollyfilla.

Plastic Māori performing at the Montreal Fringe Festival, Canada, 2005.

Mika and Hamilton threw themselves into their research, cheerfully attending tourist shows and talking to producers, rigorously schooling their performers both in the diverse practices that make up the genre and in how to work the tourist audience effectively. They were designing a great night out – one that could live up to the high price tag. But the venture was doomed from the start, plagued by delays and cost overruns. Almost immediately after it opened, Paul stopped paying the company, and so they walked off.

Without a show, the whole thing quickly collapsed into bankruptcy, provoking headlines and bestowing an infamy on Paul that is still being revisited, more than ten years on, in the popular press and even in academic journals.12 Mika says their defection and its immediate effects should not have been surprising: ‘Odd that when our show didn’t go there was no Rawaka. No one really thought about that at the time. Suzanne had good intentions. Whatever. It just didn’t work. They ran out of money to pay us, so we stopped.’

Even as he pulled his company off the stage, Mika seems to have done his best to cover for her, telling reporters for the New Zealand Herald that the disruption to the scheduled shows was due to a double booking: the company was headed to Wellington to film Mika Live, Mika’s first show for Māori TV: ‘There was no talk about it [Rawaka] going belly up. In fact Suzanne is keen to see us give regular performances despite this time of year [winter] being a bad time for tourism ventures.’13

Looking back, he still refuses to indulge in negativity: ‘I still think Suzanne was remarkable as a Pākehā woman for being willing to make work with us.’ After all, the project gave him the opportunity to enlarge his company to twelve well-trained and seasoned dancers, Māori and Pacific kids who were able to earn a living performing for six months. Creating the show expanded his repertoire, grounding it further in Māori performance practices. Most importantly, though, the Rawaka job kept the coffers full long enough to make it possible for him to look around for a more viable platform.

At the Adelaide Cabaret Festival, 2002. The costume is by DeeZaStar: a leather piupiu made out of car upholstery. Photo by Nick Vovers.

Self-promoting’s just part of the job.

— Mika, on Gay Talk Tonight