‘Mika Versus Fashion’ poster. Launched at New Zealand Fashion Week 2010 and staged again at SXSW, the South by Southwest music and film festival, in Austin, Texas, 2015. Photo by Sara Orme; poster designed by Marcial Conacco III. The ‘Mika’ font, designed by Supply, won a Gold Pin for Small Brand Identity in the 2011 Best Design Awards.

CHAPTER EIGHT

MIKA’S MAGIC GARDEN OF AROHA

Want to buy some illusions,

Slightly used, just like new?

— Marlene Dietrich, in A Foreign Affair

People ask if my costume is traditional Māori. I say yes.

Why not? The piupiu was made up by the white man as well.

— Mika

COME ON DOWN TO MIKA LAND

The first decade of the twenty-first century started uneasily, with a kind of millennial fever. The fear of our computers shutting down and other apocalypses washed over the country. The rise of social media disrupted our sense of isolation, made us feel like players on the world’s stages even though we remained far away. The injuries of colonisation and urbanisation lingered, in spite of the way the use of te reo in civic ceremonies became commonplace. Civil unions were offered to straight and gay couples alike, and the movement towards gay marriage gathered steam. There were tensions, sure, especially around immigration, which pitted biculturalism against multiculturalism in an artificial cultural conflict designed, it seems, to maintain the dominance of the dominant culture regardless. A certain complacency about Aotearoa New Zealand as a progressive place where the natives were post-the-colonial served as a kind of comfort, especially in comparison to what we saw going on overseas, in particular in the USA. They had George Bush and Dick Cheney. We had Helen Clark and Michael Cullen. They built bubbles that were bound to pop, devastating large swaths of their population during the 2008 global financial crisis. We balanced the books, if not in favour of the working-class and poor, then at least not so obviously in support of corporations – until they got Barack Obama and we got John Key.

Somehow we maintained an uneasy coolness even as our new government began to shop us around.1 The USA threw the game to industry and outsourced work that formerly sustained their middle class. Their monumental event was 9/11 – shocking, worthy of sympathy from this distance – and then they went to war with the world, and our sympathies turned to righteous condemnation. Elsewhere there were crazy, scary diseases like SARS, and horrible outbreaks of infections brought about by industrialised farming. Here, if not completely organic and cage-free, we were not so much at risk except, perhaps, of being infiltrated by foreign agents.2 Much later, at decade’s end, we had the Christchurch earthquakes and the Pike River Mine disaster, and the world looked at us, briefly, as a place where tragedy could, in fact, strike.

Above all, towards the end of the noughties, New Zealand began to fancy itself a player on the world stage, fuelled by easy travel both ways and an accelerating flow of cultural capital via the media and the internet. The big-screen successes of The Piano and Once Were Warriors in the 1990s, and Whale Rider in 2002, like Green Dolphin Street decades before, had seen images of exotic South Seas islands and islanders projected into the international imaginary. New Zealand was hitting the big time on small screens, too, with shows like Xena: Warrior Princess (1995–2001) and Flight of the Conchords (2007–9). Where Xena was an epic American series set into the New Zealand landscape, Flight of the Conchords was a New Zealand-esque comedy set into New York City performed with ironic naïveté by Bret McKenzie and Jemaine Clement. Flight of the Conchords had been a hit on the cabaret stages at Edinburgh in 2002 and 2003, and after specials and guest gigs on American and British radio and television, they went on to HBO for two seasons, charming their audiences with tall tales about short poppies, singing and stumbling through the not-so-nice streets of the big city.3 As it falls into a rather classic fish-out-of-water genre, the show is slightly queer, or at least not completely straight, in the way that New Zealand men often seem almost, but not quite, like American men. Clement and McKenzie tilt just a tiny bit off the masculinity scale whilst also creating self-aware – or at least self-conscious – comic commentaries on the challenges, and compromises, that come with chasing conventional success: getting the gig, getting the girl, getting one up on the competition. Their performances dance around the real rough edges of difference(s), all the while smoothing the edges and making nice.

Mika, Carmen and Jay Tewake at the 2009 Sydney Mardi Gras – Jay’s first. Mika recalls that ‘Carmen drove her scooter up Oxford Street as the TVNZ Close Up crew followed them, filming for Air New Zealand’s Pink Flight’. Photo by Pierre Godquin.

Mika Live filming at Avalon Studios, 2004. Mika filming his intro.

Mika Live filming at Avalon Studios, 2004. Left to right, Nancy Wijohn, Taupuhi Toki, Ramegus Te Wake, Lady Sai‘ifiti, Mika, Sariah Witika, Mokoera Te Amo and Renee Winter. (Also there, but not in the shot, is Robert Gatu.) Mika Live was created by Mika and Mark James Hamilton, directed for television by Wayne Leonard and co-produced with Paora Maxwell’s production company for Māori TV.

Mika didn’t do that. He kept coming home, kept re-mixing it up, this time for Māori Television, which was launched on 28 March 2004 after decades of political wrangling and controversy. Mika was almost immediately offered a contract: ‘Just in the nick of time, Māori TV came to us, and Mika Live – my first TV series – was born.’4 Mika Live and its successors – Te Mika Show, Kā Life and, more recently, Matika5 – mix te reo and English in song, dance and chat with endearing good cheer. Both Mika Live and Te Mika Show were staged as ‘live’ with studio audiences, as such following and parodying the conventions of countless variety shows, especially those of the 1960s and 1970s, with the same gleeful camp consciousness that Mika brings to his stage shows. Having promised himself, after Shark in the Park and The Piano, that he would make his own way onto the screen, there he was, not only ready for his close-up, but commanding it, performing the impresario, with a coterie of other performers – Torotoro and (when the first group of kids disbanded) the Plastic Māori, along with diverse celebrities and assorted ordinaries – swirling around him.6

Mika Live in 2004, with Prime Minister Helen Clark, Mika, ‘Auntie Mabel’ Wharekawa-Burt, and Denise L’Estrange-Corbet from WORLD.

COME ON PEOPLE, FLY AIR MIKA TONIGHT

Hunched over an old-time standing mic, dressed in a seventies psychedelic shirt, cupping his ear, Mika begins as if introducing a children’s story: ‘Kia ora whānau. In a far far away land, there lived . . .’ And the ensemble picks it up: ‘Mika, Mika Mika Mika Mika, Meek Meek Meek, Mika!’ He sings:

Nau mai haere mai

Enter our world.

Come on groovy people

Shake your pearl.

Get it all together and then

Come on down to Mika land.

Your favourite TV show . . .

La la la la la la.

Launched in 2006, and available now on DVD, Te Mika Show is a colourful bricolage. The primary set looks like a mock-up of Pee-wee Herman’s already parodic playhouse with its brightly painted, eccentrically skewed flats and platforms. There’s a dance floor, and a stage for the band. For the ‘Air Mika’ segments, in which he interviews celebrities and politicians (Carmen, John Campbell, Georgina Beyer, Helen Clark, Manu Bennett, Stacey Morrison, Tina Cross . . .), there’s a ‘plane’: curved walls, hand-me-down carpet, swivel chairs ready to swerve at the first sign of turbulence, perky flight crew in Trekkie costumes. The costumes mix and match pieces from Mika’s stage shows: the Star Trek get-ups from his UhuRa days, professorial drag for the quiz sequence, loads of sequins and other shiny bits, and native drag for the Plastic Māori, the girl dancers and Mika. Pollyfilla wafts in to run the crafting contest.7 The young dancers get a chance to shine, and the show closes with a flashy song-and-dance number in high Mika style.

Te Mika Show, 2006. Georgina Beyer was one of the many stars who guested on the show; here she is with Mika and the full cast performing the Love Boat theme song. The dancers are Mokoera Te Amo, Kasina Campbell and Taupuhi Toki, with Jai Campbell, Ellen-Moana Smith, Alannah Curtis, Ashleigh Mackinven, Charles Martin, Gina Oge, Jamie Blomfield, Kirby Valasi, Nigel Warasi and Ricky Olo, as well as guests the Ceroc Dancers: Jazz Lopez, Pete Thomas, Natalie Perry and Thareeza Whitehouse. Costumes by Pollyfilla. Photo by Sanjaia Daji.

Kasina Campbell, Mika and Pollyfilla fly ‘Air Mika’. Te Mika Show, 2006. Photo by Sanjaia Daji.

It’s all great fun, but there’s a serious thread or two running throughout. In ‘Pā Cinema’ Mika showcases independent films that otherwise might not reach a wider audience, in so doing not only offering us a fascinating glimpse of seldom-seen work, but also aligning himself with their high art and social sensibilities. The celebrity interviews revolve around issues like alcohol and drug addiction, or youth suicide, or bullying – ‘Things don’t have to be looking like Once Were Warriors before you’ve got a problem’ – with helpline contact details on the screen. It’s not so much that the show veers away from the frivolous to offer sermons of self- and get-help. For that matter, it’s not that the show is preaching political correctness by presenting a widely inclusive image of New Zealand society: a stage shared by people of every possible social orientation. It’s Mika land. Everyone is whānau. Everyone is vital – both necessary and fully alive. We’re together in this, and our bodies are intimately attached to our thinking, feeling selves. This is a party, and we’re all invited to bring ourselves to it.

Beyond the noughties, the later shows leave liveness behind and take on the conventions of morning programmes, without the studio audience. They are more visibly polished and explicitly focused on physical and spiritual well-being. The most recent programme, Matika (2015), is billed as ‘a healthy entertainment series for morning viewers’: ‘From unmotivated rangatahi [youths] and plus-sized pākeke [adults] to aging kaumātua [elderly], this half-hour life-changing television has it all: Wellness Warriors, Healing Gurus to Happiness Hunters in real spaces, from forests to kitchens to work stations.’8 While Mika is front and centre as MC and impresario for the early shows, he pulls back here. Instead, we see Mokoera Te Amo step into the frame to speak directly about issues in Māori health and to show us how to maintain fitness through Māori and other physical practices. Each episode also offers a cooking demonstration by Hariata Tai Rakena and interviews by Lani Lopez, along with ‘it gets better’ stories from participants in Mika’s Aroha Project who tell us how they have struggled with and surmounted the effects of bullying. The array of personae is racially diverse and gender-fluid in a matter-of-fact, unselfconscious way. There’s more te reo Māori than English, and few concessions; if we don’t know the words, we can figure them out from the context (or not). The show is as body-centred as ever, but it’s also intently spiritual, about vitality in the fullest sense of the experience, and essentially social, about how we live in this world, together, for worse or for better.

It looks like Mika’s gone straight in Matika – the song and dance, variety-show camp stripped back to reveal an un-Wildean importance of being earnest. But ten years on from his first television experiments, he no longer needs to slide his audience along in quite the same way. More of them – especially the younger ones who’ve been to kōhanga reo and otherwise immersed in the culture – understand the language enough to get by. Identity politics are not so much a thing of the past as a part of everyday discourse. ‘If you’re not authentic, then you’re just lost,’ says one man being interviewed by Lani Lopez on the question of ‘Mana Tāne/Male Integrity’, adding: ‘Every Māori man should know at least one haka, and have at least one suit, and just carry yourself as a gentleman.’9 There is an echo of the neoliberal idealisation of the individual at the expense of everything social here, or there would be were it not for the constant communalism we see performed.

Backstage at Te Mika Show, 2006. Glenys John is applying final touches to Mika’s Madonna impersonation, a mix of ‘Hung Up’ and ‘Frozen’.

Backstage at Te Mika Show, 2006. Colin McLean (aka Pollyfilla) checks Mika’s wig and costume.

Backstage at Te Mika Show, 2006. Mika checks his Madonna look once more before the shoot.

Backstage at Te Mika Show, 2006. ‘Mika. Rhymes with Madonna.’ Photos by Sanjaia Daji.

Mokoera Te Amo with Mika in Plastic Māori, 2005.

I HAD TO WALK SEPARATELY EVERYWHERE

The noughties were good to Mika. He was totally in charge as the executive producer for Te Mika Show, still hitting the boards for live shows and getting loads of great publicity. But he was restless. Torotoro dissolved, and in their place the Plastic Māori stepped up for their first concert during the St-Ambroise Montreal Fringe Festival in 2005. The audiences were there, but, he says:

The festival was a waste of time for me. We were lucky to have Erica Crawford’s bunch book us for some styley clubbing, dinners and generally cool stuff whilst the Montreal Fringe was full of dirty smelly artists who seemed to always be drunk and smoking. That was enough to get us to Edinburgh, and then I went on to Paris.

What else could he do?

By 2007 I’d had enough of that. I started to travel again. I did Tribal Hollywood in Tokyo. Then I went to Moscow to join Donatella Versace and the likes for one of fashion guru Suzy Menkes’ events, Thailand to write, Los Angeles, Las Vegas to meet bookers for new shows . . . time for a change. Many changes.

He was working non-stop in New Zealand as well: appearing at Fashion Week, and on Shortland Street in a bright green sequinned dress as ‘Eva Destruction’. Other people’s projects paid well and kept him in the public eye, but at the same time, playing to the expectations of others, even within the confines of his own television show, made him edgy, looking outside the box for the next new thing.

Festivals were unsatisfying, but they served a purpose, provided a destination and a platform. He was almost continually on the road, expanding his flight path to Cuba and Russia.

My friend Dañiel said ‘they want some Māori to go to Cuba for the Holguín Festival’ and so I said ‘yeah yeah yeah, I’d love to go’. All I knew was that the US hates Cuba, so going from Las Vegas, I had to go to Mexico to get the visa. I arrived in Cuba, got to the hotel, got up the next morning, opened the curtains . . . my God, I couldn’t believe it. A city with no McDonalds, no Coca-Cola . . . Once upon a time in New Zealand we didn’t have these things either, little towns.

Mika in Holguín (opposite) and Havana (below) for performances at the Romerías de Mayo Festival, 2008, just after Castro’s daughter held the first gay rights conference in Cuba. The kaftan is by Strangely Normal.

The absence of American popular culture was not the only socio-temporal throwback in Cuba. There were vivid reminders of the hazards of being gay before homosexual law reform in New Zealand: ‘I was lucky to have my friends Dañiel, Tata and Alexander to go clubbing with. But even so I had to walk separately everywhere, so that they wouldn’t get hauled up by the police. They couldn’t be in my hotel room, or they would be arrested.’ To be nostalgic for a pre-globalised, de-mediatised New Zealand seems perverse. His home-town experience was, after all, repressive and largely life-denying. But it gave him something to push against.

Mika in Holguín, Cuba, 2008. ‘The outfit, by Patrick Steele, caused a communist scare.’

So did Castro’s Cuba. He had a visit before the opening night gala. Government agents knocked on his hotel room door. They asked: ‘Are you going to perform naked?’ Long pause. Mika, thinking to himself ‘oh my God, I’m going to die now’, answered: ‘I’m not being paid enough to perform naked.’ Then they nodded a bit, said, ‘Well, you’re an artist, so we understand,’ and left. The show went on.

Castro’s daughter was holding the first meeting about gay rights but I couldn’t get to it. To perform, I was in a Patrick Steele, skin-tight flesh-coloured body suit, with an Issey Miyake cloak, on a rooftop, outdoors. It was packed, with the audience all around me. I sang in Māori and Spanish and kissed a young woman and a young man. A day earlier the boy might have been arrested.

Being foreign is familiar to Mika, a way of recalling himself. After all, he started life with another name, as an outsider who could pass only so far in the halls of his high school and who made his name through performances of self-fashioning:

When I travel I like either to disappear or to stand out. In Cuba, I was definitely standing out. I sang ‘Wind Beneath my Wings’ – a version made for me, in 1990, where I sang it for the first time in Adelaide – and this came back to me, because there I was again travelling alone.

In Cuba he was free again to make it up as he went along, liberated by estrangement: ‘People asked if my costume was traditional Māori. I said yes. Why not? The piupiu was made up by the white man as well.’ But again it wasn’t enough, he says. ‘I like being able to discover things when I’m alone, but I’m not so sure I like performing so alone.’

A WHIRLWIND OF EROTIC JOY

Mika can be cavalierly dismissive about arts festivals, the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in particular. But these events are much more than showcases for entrepreneurial performing artists, where they hope to do more than break even. They are meeting places, and business places. The Edinburgh Fringe, in particular, is the most well-known of transnational platforms to which they aspire and from which they launch, many of them, tours throughout the wider world. Edinburgh doesn’t incubate so much as it percolates. Every year the city fills itself to the brim with producers, promoters and performers who are there as much to see as to be seen, inspiring and inspired, circulating and connecting, cutting deals and concocting plans, when not simply comparing notes and trashing the competition. Edinburgh is where Mika met the Indo-Japanese performance artist Shakti:

One night, Mark James said, ‘Why don’t you go down and see Shakti?’ I saw this woman doing a burlesque that was like mine, and went back and back and back. We’ve been communicating and collaborating ever since, and each time it’s a richer experience.

Mika and Shakti at an overseas airport lounge, 2009.

Shakti and Mika in the poster for Night of the Milky Way Galaxy (2011), based on the classic fantasy novel by Kenji Miyazawa. Performances in Tokyo and Kyoto raised money for the victims of the Japan earthquake.

The encounter with Shakti rocked Mika away from the bicultural paradigm in a new way. He’d rolled with African American culture and arts – not merely identifying with pop stars and fashion icons, but doing it close-up, starting in the early 1980s with the Pomo Afro Homos. And yet this was different, somehow.

Shakti is the first woman, a fiery independent soul, who I see as my equivalent. She fills me with something I can’t find here, outside the Māori–Pākehā relations where there’s so much baggage. Māori–Pākehā collaborations are generally so wrought with PC and nonsense that I’ve tried on the main to avoid them. Shakti and I don’t care about how the world judges us. She’s Indo-Japanese. I’m a Māori mix. Her father worked for Mahatma Gandhi, my father . . . well . . .

Shakti is, like Mika, intensely and continuously engaged in self-fashioning. Her freedoms are sexual as well as cultural, finding expression in performances that defy easy readings, although, as with Mika’s performances, that doesn’t seem to stop reviewers from trying it on. The press release for the West End transfer of Shakti’s 2002 show, The Pillow Book, promotes her performance as a ‘glorious celebration of women’s sexuality’ in which she ‘ends up completely naked, her body a canvas for beautiful day-glo painted images, whipping herself into an almost-demonic, explosive finale of passion and fire’.10 Shakti is a serious artist, well and truly trained in dance and performance across diverse cultures, beginning with the Indian and Japanese forms inherited from her parents, as the release assures reviewers and prospective ticket-buyers: ‘Shakti studied modern dance with Martha Graham [and] Alvin Ailey and jazz dance with Luigi. Upon returning to Japan, Shakti developed a unique hybrid form of dance blending an array of Eastern dance traditions and yoga with Western jazz and contemporary rock resulting in an exotic, erotic, and shocking effect.’11 The photo of Shakti that accompanies the text shows her naked except for swipes of colourful paint, arched back into semi-profile, arm flung over her head, eyes closed as if moments from orgasm.

Mika saw his own mix-and-match performativity and exuberant sexuality reflected in hers. Like him, she dances between high and low art. In the same release, Donald Huttera of Dance Now asks, ‘Was it kitsch?’ and adds: ‘If so, of an artfully high order. Shakti was magnificent!’ Paired as it was with the more middle-class but no less woman’s-body-centric Vagina Monologues, Shakti’s performance is pitched between pleasure and politics: women’s liberation.12

HERE, THERE AND EVERYWHERE

Television is magic. It makes celebrities of the most mundane performers (and objects). Being a hit overseas works wonders in certain circles, but creating and starring in a TV show magnifies the performer’s image and circulates it to all and sundry transformatively. Mika was now world famous in New Zealand, too, and he was still swinging: between fringe and main stages, between commercial and avant-garde platforms, between familiar and experimental repertoires, between the conventional and the out-there, and between the here and the elsewhere, from South Island to North and far, far beyond. In 2009, Mika travelled to Kerala, India, with Mark James Hamilton and some of the Torotoro dancers to work with Samudra, a pair of acrobatic dancers who mix traditional South Indian martial arts practices with modern dance techniques, on a show.13 Then he went again to Tokyo to work with Shakti. There were digital displays of poetic shapeshifting attached to two exhibitions at the Auckland War Memorial Museum: ‘The Mystery of the Orchid’ and ‘The Magic of the Rose’.14 He made a triumphal return to his home town, for the cabaret in the Timaru Boys’ High School hall that I saw in 2010. And then, reaching a new pinnacle of sorts, he staged the Aroha Festival, featuring Pō / Beautiful Darkness at the Aotea Centre in Auckland that March.

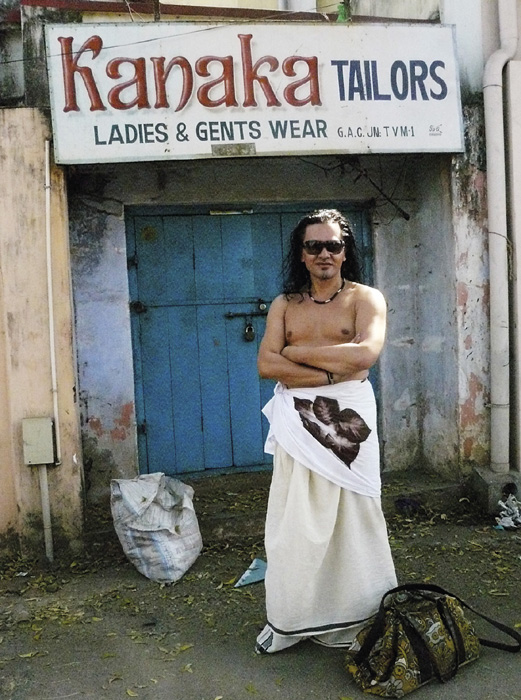

Mika in India, 2009, while on tour with Mark James Hamilton and Torotoro, part of an ongoing collaboration with Madhu Gopinath and Vakkom Sajeev, co-directors of the Samudra Centre for Indian Contemporary Performing Arts in Kerala. Photo by Seona Robinson.

Mika in India, 2009.

Mika with Samudra Festival co-director Vakkom Sajeev, 2009. Photos by Seona Robinson.

Torotoro and Samudra together in India, 2009. Torotoro were Kasina Campbell, Taupuhi Toki and Mokoera Te Amo, directed by Mika and Mark James Hamilton. Vakkom Sajeev and Madhu Gopinath directed Samudra.

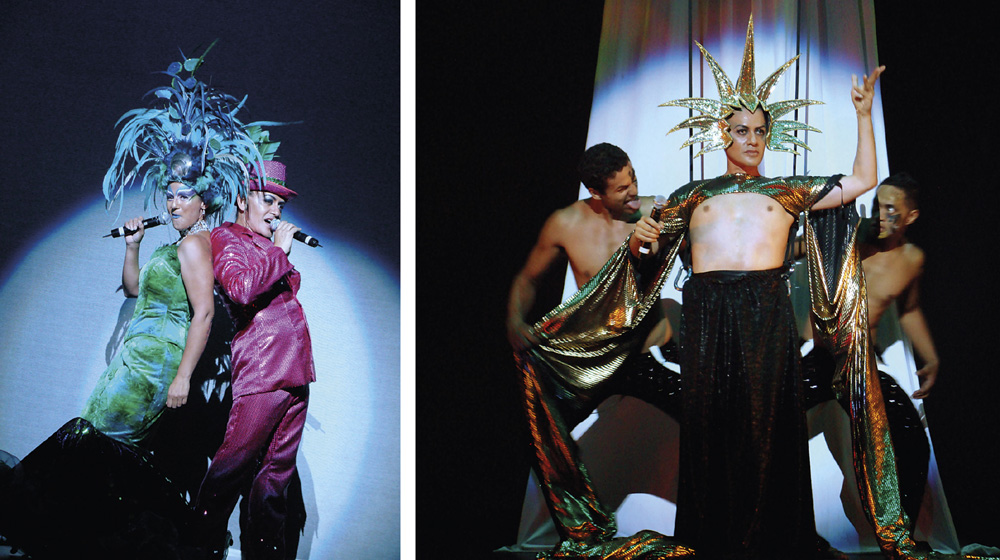

For Pō / Beautiful Darkness, Mika brought together old collaborators with new, including the Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra and Gareth Farr, to create what they called a ‘Tribal Pop Opera’. Pō was an eclectic showcase. Hamilton performed Bharatanatyam. Shakti did her thing. Jackie Clarke sang. And Mika wafted through it all, accompanied by four beautiful, shirtless young Māori men he’d trained as his back-up singers and dancers: the soon-to-be JGeek and the Geeks (Jermaine Leef, Parai Parai, Marino Taiatini, and Jay Tewake), who went on to a kind of fame of their own with their hit ‘Māori Boy’ soon thereafter.15 The show was on the main stage at Auckland’s Aotea Centre as part of the first Aroha Festival, which Mika had organised as a successor to the Hero Parades and parties. The remarkably diverse audience included Auckland’s mayor, John Banks, who made a speech at the pre-show cocktail party, and three statuesque, cross-dressed ‘Supremes’ circulating among us serving condoms, instead of canapés, from large silver platters.

Stefan Knight making up Mika for ‘Wonderland: The Mystery of the Orchid and The Magic of the Rose’, a series of spoken-word performances presented by the Auckland War Memorial Museum, 2009. Commissioned by Vanda Vitali, written by Mika, edited by Mark James Hamilton and filmed by Supply (director: Piri Tukere).

With JGeek and the Geeks. Left to right: Jermaine Leef, Mika, Marino Taiatini, Parai Parai and Sonny Bishop (lying on the floor). The band, developed through Mika’s Emerging Leaders Programme, had a hit song in 2011 with ‘Māori Boy’.

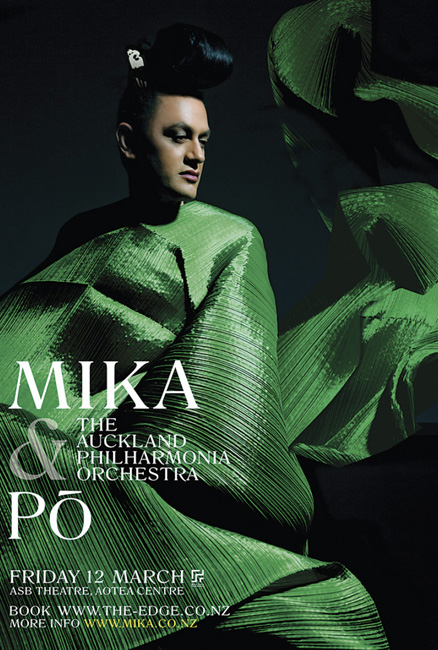

The poster for Pō / Beautiful Darkness, Pasifika Festival, Aotea Centre, Auckland, 2010. Photo by Greg Coomb; poster design by Supply. Mika wears Issey Miyake. Penny Dodd arranged music for the Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra, conducted by Hamish McKeich. Costumes by Pollyfilla.

Mika and Penny Dodd watching a rehearsal.

Pō’s mash-up of performers and practices juxtaposed the bicultural – Mika and the boys, Mika and Jackie out-diva-ing each other with ‘Do U Like What U See’ – with the multicultural: everything else. The multicultural lost. In the end, we saw Mika suspended in a harness high above the stage, singing ‘Want to Buy Some Illusions’. Like Marlene Dietrich, he was not quite playing it straight as the stage was stripped away beneath him. Stranded for a moment, alone, he let go of the trappings of stardom, and of Māoridom, and slowly came to ground on the bare stage. There, he took off his gold lamé ‘wings’ – metres of shimmery fabric – and his glittery crown, made of pieces of broken mirror like a mirror ball, and leaned them against the now-empty harness before walking off stage.

Pō / Beautiful Darkness: Jackie Clarke and Mika singing ‘Do U Like What U See’ (left) and Jermaine Leef, Mika and Parai Parai in ‘Ahi Wai’ (right).

And then he came back for the applause.

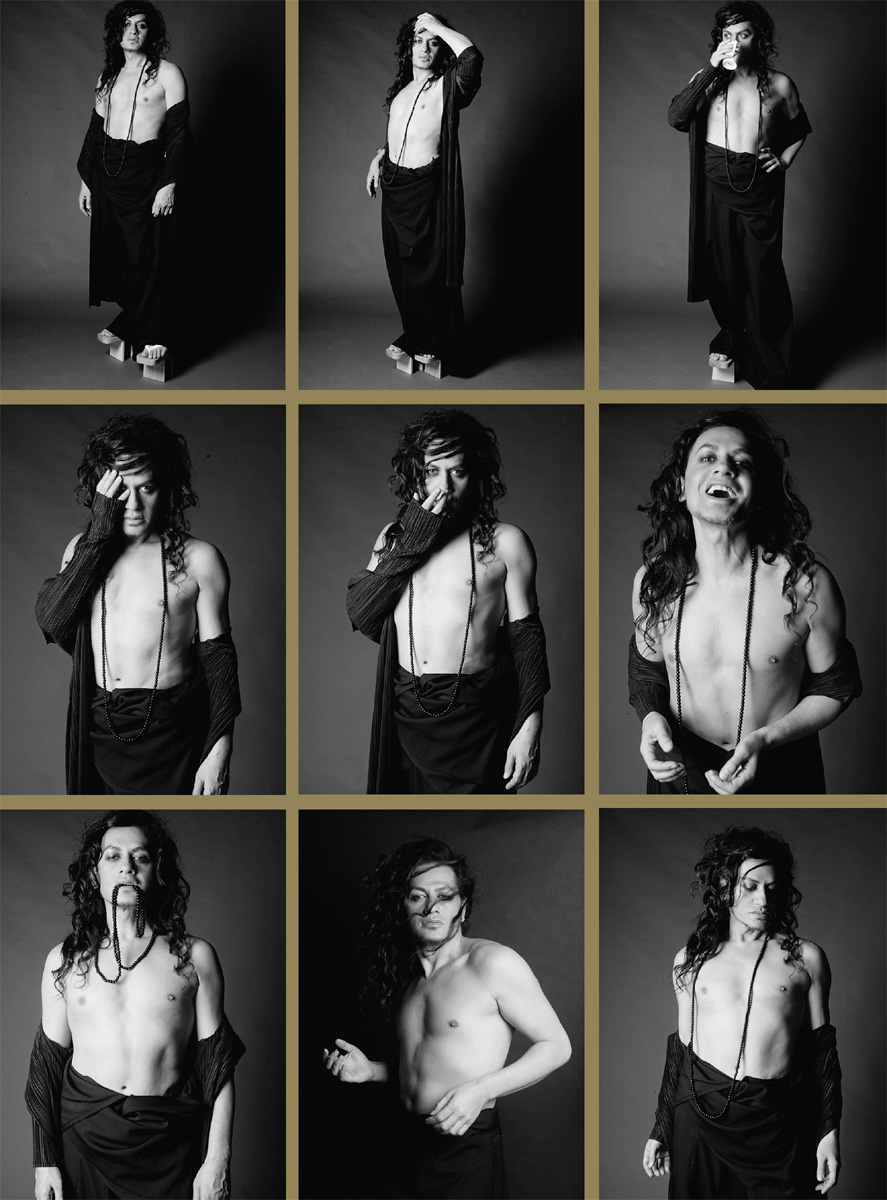

Sara Orme shoots Mika, 2010. Mika and Sara first began working together in 1999.

Take my lovely illusions –

Some for laughs, some for tears.

— Marlene Dietrich