‘Māori Barbarella’, from a shoot for Salon Mika, 2014. Korowai by Kiri Nathan. Photo by Sara Orme.

CHAPTER NINE

TOHUNGA MATAKITE

Camp itself should almost be defined as a kind of madness, a rip in the fabric of reality that we need to reclaim in order to defeat the truly inauthentic, cynical and deeply reactionary camp – or anti-camp – tendencies of the new world order.

— Bruce LaBruce, ‘Notes on Camp/Anti-Camp’

Look New Zealand, I’m a traditional Māori!

— Mika

A PARTY BORN OF AROHA

September 2011. Auckland is hosting the Rugby World Cup. It’s a big deal for the city and for the country. A huge influx of tourists, celebrity spectators and international media: we are, for a moment, what the world is watching.1 In the near-darkness as spectators gather, we hear sounds of a haka mixing with the long notes of several pūkāea (long wooden trumpets), and then a woman’s voice soars above the chatter, her karanga hailing everyone from far and near, summoning us to the show. Other voices, female and male, join hers, and the vast stage is soon swarming with Māori – well over fifty men, women and children – in traditional costume, performing a haka pōwhiri, singing and dancing their welcome in front of thousands of spectators. What follows is an impeccably scripted and choreographed pageant, the story of Aotearoa New Zealand, a nation that has emerged from its native and colonial past to celebrate its multicultural present. With 760 performers plus crews supporting both the live action and the filming for broadcast to audiences in New Zealand and beyond, it’s magnificently theatrical, marvellously inclusive and absolutely massive. And while there was a similar show on at Eden Park – cast and crew of a thousand or so, starting with Māori and culminating in a valorisation of contemporary, postcolonial, post-bicultural New Zealand – to launch the World Cup just a few days before, this show’s at Britomart’s Takutai Square, and it’s all Mika: Mika’s Aroha Mardi Gras.2

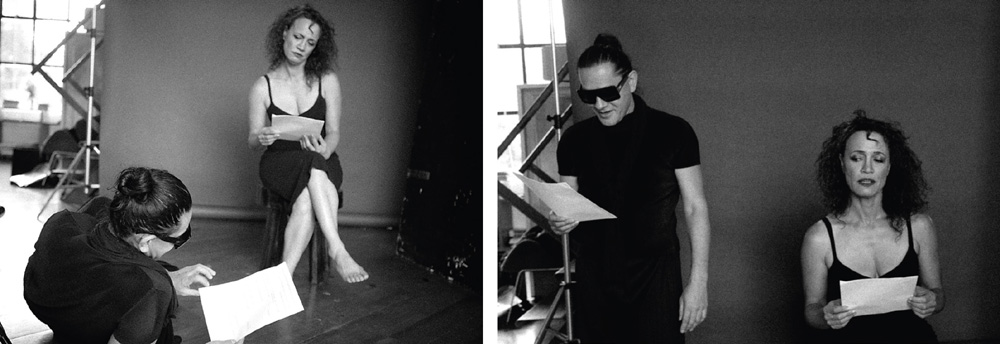

Mika and Rena Owen in rehearsal for the Rugby World Cup Aroha Mardi Gras, Auckland, 2011. Photos by Sara Orme.

In the film of the event, we see Rena Owen take the stage in a beauti ful frock designed (as many of the key costumes were) by Kiri Nathan. Seated with a big book, from which she reads periodically, she becomes our guide, a poised counterpoint to Mika’s perpetual-motion performance as MC.

A millennium ago, our ancestors arrived in Aotearoa, the land of the long white cloud, now known to all as New Zealand. Our stories, our tradition and our culture were passed down orally through song, dance, chant, performance. Tonight we celebrate the multicultural heritage of our country, to bring you a taste of how this land became the current party destination of the world. . . . Welcome, welcome, thrice welcome to Mika’s Mardi Gras!

The crowd cheers, and the show pours onto the stage, seemingly from all sides. She announces: ‘And so people, our party continues. A party born of aroha. Love. A party to welcome you to our city, to our culture. A party where you can, and should, expect the unexpected.’

The Haere Mai Taiko Drummers keep the beat, mixing seamlessly with whatever’s next: from the Te Tai Tonga Kapa Haka troupe, the Te Ariki Vaine Polynesian Dance Team, the Pearlz of Meganesianz fa’afafine dance troupe, the AUT Dance Team and the Kā 400 kids (really, 400 kids!) led by Jay Tewake to The Glamboyz, Haka Punks, Pounamu Diamonds, The Manu Dolls and the Phoenix & Tais Belly Dancers. There’s a burlesque performer, Miss Leda Petit. There are drag queens who take the spotlight in showgirl pink, feathers and sequins. There’s a fashion show, models runway-walking in designs by Kiri Nathan. There’s Mika singing duets with Edward Ru, Mahina Kaui and Keisha Castle-Hughes (in her first venture as a singer). He is himself a one-man fashion parade racing through, stitching the whole thing together with a constant patter to the audience. In one of his more flamboyant costumes, he stops, finds the camera and proclaims: ‘Look New Zealand, I’m a traditional Māori!’ In another he swans a bit, waving his voluminous parachute silk cape over the wind machine, then smirks, ‘I wear this one to New World, Mt Roskill.’3

Seen on the screen, more than five years later, the show still feels fresh, as if we can be forever there, part of the party. It is indeed, as Mika exclaims, ‘A beautiful night!’ He crosses the boundary separating stage and audience, between the live and the mediated performance, tells us to ‘feel the love in the air’, wiggles his finger (naughty, naughty) and goes on: ‘Some of you are even touching. . . . And for one night only. Let’s not give a dingle dingle about what anyone else in the whole wide world . . .’ He doesn’t finish, but we know what he means. This is, after all, part of the Aroha Festival, also produced by Mika: a cosmopolitan promenade that visibly embraces gender and sexual diversity as part and parcel of the rich cultural tapestry of contemporary New Zealand. It’s a celebration of all kinds of love – tribal and familial, between friends and between communities, platonic perhaps for some, but also undeniably erotic: ‘Shake, feel, kiss me, love me . . . start a fire.’

Rugby World Cup Aroha Mardi Gras, 2011. Southside diva Chanel D’vinci (left) performs ‘Get It On’ by Mika. The song, says Mika, ‘was a fun way to inspire condom use for safe sex’. Jay Tewake is in the back leading the Haka Punks dance crew. Trajano Leydet stands far left. Mika’s costume by Polyfilla.

Mika and his all-stars at the very alternative RWC Aroha Mardi Gras, 2011. From left, Pounamu Diamonds, Leda Petit, Mika, Kelly Henare-Heke, Edward Ru.

Mika’s Aroha Mardi Gras was, he says looking back, ‘the biggest thing I’ve ever done’. To make a show that looks so spontaneously combusted requires months and months of disciplined preparation, countless conversations (and certain compromises) with collaborators and sponsors, detailed design and direction aimed both at the live audience and for the cameras. For her part, Kiri Nathan says that Mika

literally slapped me in the face with his take the world by storm attitude to life and work! I spent 6mths [sic] working on his Aroha Mardi Gras Event during the RUGBY WORLD CUP. It was an insane, creative, learning period. I went from making a few signature pieces for Mika to creating all of his costuming, dressing the main cast, Keisha Castle-Hughes & Rena Owen to name a few and styling the entire show and CAST OF OVER 600 people. I did everything from physically dressing Mika to holding the wind machine for optimal costume performance. . . . Most of the pieces I created for this show were hand woven and hand sewn, it really was creativity outside the box. I loved it!4

Every one of the 760 people on the stage looks confident and absolutely thrilled to be there. Every step, every note, what they are wearing, the way they keep the beat is explicitly performative. ‘We know who we are, because this is the way our people – native and not-so, queer and not-so, young and not-so – have always danced, we’re making these dances new with each other and for you, and we will still be dancing, here and elsewhere, long after this night is over.’ Thus they recall the past into the present and summon the future. Everyone is applauded, not because of political correctness, but because of the way the vitality on the stage flows into and lifts the audience. Twenty years after Mika’s first gay haka, at the Hero Party on Princes Wharf, only a few hundred metres away from Takutai Square, the show carries on.

Poster for RWC Aroha Mardi Gras, 2011.

Keisha Castle-Hughes with Mika in Los Angeles, recording the song she performed at the RWC Aroha Mardi Gras in 2011, which later became the title track for the stage show and film Room 1334 (2015).

AN ARTISTIC MINORITY REPORT

The distance (physical and metaphysical) between the two Rugby World Cup spectaculars is instructive. Transgender academic/activist and prolific theatre critic Lexie Matheson saw the show as standing alongside the larger event, rather fraternally, as ‘the artistic equivalent of a minority report’.5 But there’s more to it. Both shows were staged for live audiences at the same time that they were choreographed for cameras, edited and packaged, preserved and transmitted to audiences in New Zealand and beyond. Mika’s street show was intrinsically local and followed the patterns he’s established over the decades of his career, dipping in and out of cabaret and burlesque, mixing and matching Māori, Pasifika and other cultural performance arts, offering a challenging and yet inclusive world view through song, dance and patter, flaunting fabulous costumes and featuring others as much as showcasing himself, and looking ad hoc in a way that can be achieved only through deliberate design and years of practice.

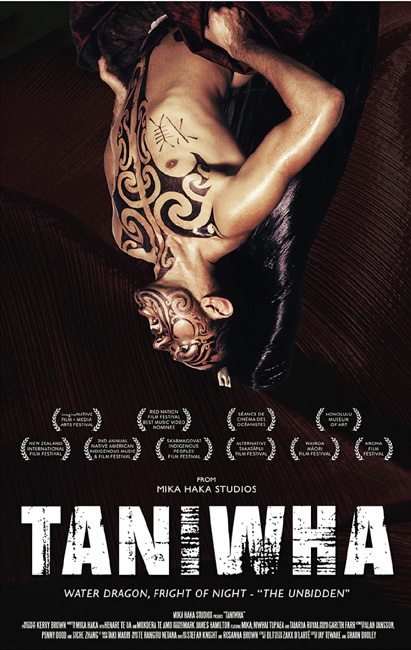

Poster for the short film Taniwha, 2015. ‘New Zealand is a land without dangerous animals, reptiles or beasts – yet beneath the fathomless depths of the Pacific lie dragons and serpents that wait, simmering for their time.’ Moko by Te Rangitu Netana. Photo by Greg Semu.

Poster for Māori after Dark / Pacific Polynesia, Māngere Arts Centre, Auckland, 2014. Produced and directed by Jay Tewake, with Mika, Siche Zhang and Taki Māori. Salon Mika image by Sara Orme.

In contrast, the show at the Eden Park stadium was flashy, but also well and truly templated, opening with the native welcome and moving through a series of set pieces in which the local culture is rendered into a collation of kitsch signifiers, culminating with a celebratory ‘we are the world’ lip-synched song-and-dance performed by a thousand or so local volunteers under the expert direction of the masterminds at David Atkins Enterprises (DAE).6 As with Olympics opening ceremonies, which DAE also regularly produce, what we see is a corporate and consumable spectacle, so completely made for television that it’s hard to imagine what the live audience might have seen. It’s gorgeous, but also entirely predictable, down to its non-native nod to the natives.

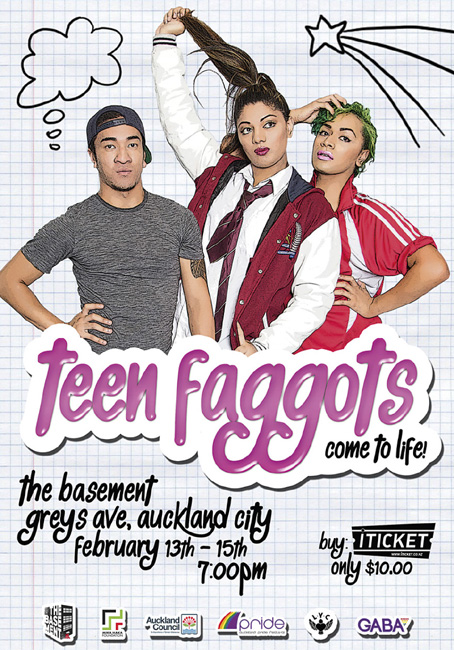

Poster for Teen Faggots, Auckland, 2014. The show, supported by the Mika Haka Foundation, was created by six LGBTIQ kids: Raukawa Tuhura, Jaycee Tanuvasa, Amanaki Prescott-Faletau, Darren Taniue, Isaac Ah-Kiong, and Todd Karehana.

In ‘Let the Games Begin: Pageants, Protests, Indigeneity (1968–2010)’, noted Australian performance scholar Helen Gilbert looks at Olympics opening ceremonies and sees the way

the theatricalized ghosts of colonialism’s Others have often haunted the performances, raising the question of whether Olympic pageants are doomed by genre, tradition, and expectation to re-enact stereotypes of cultural difference for audiences that cannot be expected to understand their subtleties. (171)

Poster for The Aroha Project, stories of survival from mental health crises, suicide, bullying, racism and transphobia by a group of emerging artists, mentored by Mika. The model, Zakk d’Larte, is a contributor. Other contributors included Lance Loughlin and Ramon Tewake, a transwoman who went on to perform in Queens of Panguru, Māori TV, 2017.

That said, she argues, these spectacles offer indigenous peoples both a platform – especially on the streets outside the stadium – and the tools to engage actively ‘in the politics of embodiment on the ground, in the moment and at the interface of cultures’ (172). For Gilbert, following Margaret Werry, indigenous participation in Olympics opening ceremonies – and other events, such as the Rugby World Cup opening in 2011 – works in much the same way that performance for tourists both confirms cultural clichés and offers opportunities to practise and preserve indigenous ways of being:

Performance, in the context of the state, is both a resource of the dominant culture (which requires repetition, participation, and witness to uphold that dominance) and of the powerless, who use it to navigate, to inhabit, and even to trick systems not of their making.7

Inviting the natives (and other locals) to walk onto the same world stage here as elsewhere serves to smooth the troubled edges both of colonial history and of the capitalist present. It makes native (and local) cultures ever more consumable, trimming away the possibility of contention, controversy or even conversation.

What performances like Mika’s Aroha Mardi Gras offer, in contrast, is not an ahistorical ‘empty space’8 or some sort of theatrical ‘utopia’.9 The diverse peoples here cross paths on the platform as they do in everyday life, performatively and with the grace required of those who are not of the dominant culture. There’s an element of ‘we’re all in this together’10 going on, to be sure. But ‘we’ are not so naïve or shortsighted, and we are not all the same regardless. These performances are exceptional in their vitality. The individuals and groups on the stage are passionate about making performances that project positive images of their identities and their communities. In the audience are friends and family, alongside many others – other Aucklanders and tourists there for a good (free) night out, and the Māori TV audience beyond. For this night only they’re all occupying Takutai Square, outside Britomart, an area that otherwise serves as an everyday meeting place and transit hub – an environment through which we all, literally and figuratively, must pass.

MIKA HAKA FOUNDATION

In an extensive overview of the 2014 Auckland Pride Festival, Lexie Matheson considers the significance of performances staged by Mika and other Māori and Pasifika artists, and the work done by the Mika Haka Foundation, directly:

Let’s not forget that the people you see on stage and applaud wildly are also part of the demographic that appears at the top of our most shameful statistics as a nation: poverty, prison muster, drug and alcohol issues, early death and suicide. Add to that fact that these kids are also queer and you have a potential time bomb just waiting to go off. All the more reason to recognise the work being done on the ground by Mika, PIPA [Pacific Institute of Performing Arts] and others.11

The Mika Haka Foundation succeeded the Torotoro Trust (2001–8) as a way of sustaining his health and education initiatives, including his current campaign against bullying. The foundation work complements his performance work and makes it meaningful as some thing beyond himself. ‘I’d realised that I was very good at raising money to support work that I believed in, and it was easier to raise money using my visibility as the hook than to ask them simply to support the kids,’ he says.

The Mika Haka Foundation’s mission, like that of the Torotoro Trust before it, is straightforward enough, even familiar: ‘to ignite young minds and transform bodies towards better lives through the performing arts and physical culture’.12 The focus on kids who have been on the receiving end of diverse forms of social violence is not, in itself, distinctive. Nor is it particularly innovative to attach an ethical imperative to performance training. Even the belief that performance empowers is fairly commonplace, at least amongst those who perform. But Mika’s role models – above all, Carmen and Dalvanius Prime – and his mentors – in particular, Merata Mita and John Draper – were exceptional. The foundation for his work as an artist and activist is the fierce, exacting and generous way he was supported when he was coming up and out. This is what he offers young people: first himself as a beacon, then the freedom to fashion themselves as he did, along with a push to make it on their own terms, and finally the expectation that when they reach a secure enough platform (or even before), they will reach around and pull others up with them.

In all of this, Mika is happy to wear the title of tohunga matakite, an accolade given to him by academic and lesbian activist Ngahuia Te Awekotuku at a ceremony honouring his contribution to the Lesbian and Gay Archives of New Zealand / Te Pūranga Takatāpui o Aotearoa in 2009. The term can be translated as something akin to ‘seer’, but perhaps in this context can be read more as pathfinder: Mika as the scout foraging forward into unfriendly terrain, hacking away at old growth, making headway via a shrewd combination of stealth and surprise attack. The work of the Mika Haka Foundation is intrinsically local, but also increasingly international. Through Kā, they’ve developed links with organisations like New York City’s Hip Hop Public Health, a group that works with artists and musicians to promote the idea that ‘healthy choices are cool choices’ to urban children and their families.13 Art and activism are also at work in Mika’s developing relationship with Native American actor/activists Saginaw Grant (Sac and Fox Nation) and Rick Mora (Yaqui/Apache). Their official reason for visiting New Zealand in 2015 was to attend the Armageddon Expo, but they spent several weeks on tour, hosted by Mika and accompanied throughout by Jay Tewake.14 At a welcoming party in the Mangere Arts Centre on 14 July 2015, Grant and Mora were greeted by the US consul general, Jim Donegan.15 For me, the evening’s festivities snatched the ‘trans-indigenous’ out of academic jargon, back into the world where it belongs.16 Mika was MC, but spent most of the evening exuberantly watching others perform – including the original members of Torotoro, who were gathered at Grant’s request and clearly thrilled to be dancing together again. Mokoera delivered a distinctive whakataukī (saying), inspiring unity. Samoan group Akavine danced. An elderly group of Cook Islanders played ukuleles and sang. And Mika pulled Whetu Fala out of her chair for a joyous and touching impromptu duet.

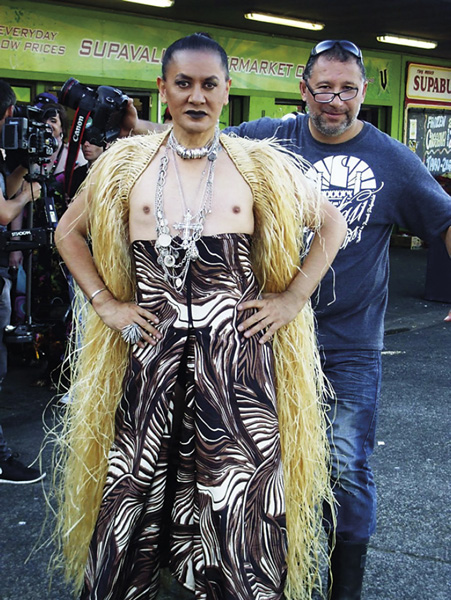

Mika calls this ‘#BusyDragDad’, New Zealand Fashion Week, 2015. Mika with emerging fashion and music talent: Zakk d’Larte, Ryan Turner and Siche Zhang.

Saginaw Grant and Mika at the American Film Market, San Diego, 2016.

THE TRUTH IS MORE DANGEROUS THAN ANYTHING I COULD MAKE UP17

Lexie Matheson has made something of an ongoing study of Mika’s work in her reviews and blog posts.18 Writing in 2015 about the Aroha Project’s Room 1334, a Valentine’s Day one-off performance in Auckland’s Basement Theatre, Matheson praises the show as ‘funny and gut-wrenching’.19 Promotional materials for the production promised to draw spectators into ‘a whare of tapu secrets that allows erotic tribalism, Shangri-La exoticism and where primal poets speak open truths’.20 The performance was a kind of pot-pourri, a stirring mix of fresh and recycled songs, sketches and spoken-word presentations at the meeting place between cabaret and musical theatre. Matheson evokes the performance’s appeal in her review:

[A]s so often happens with queer theatre, just when it borders on the maudlin and there’s a risk of self-pity, Mika breaks the spell with a new costume, a new wig, and the tart observation that ‘I look like fucking Beyoncé’.

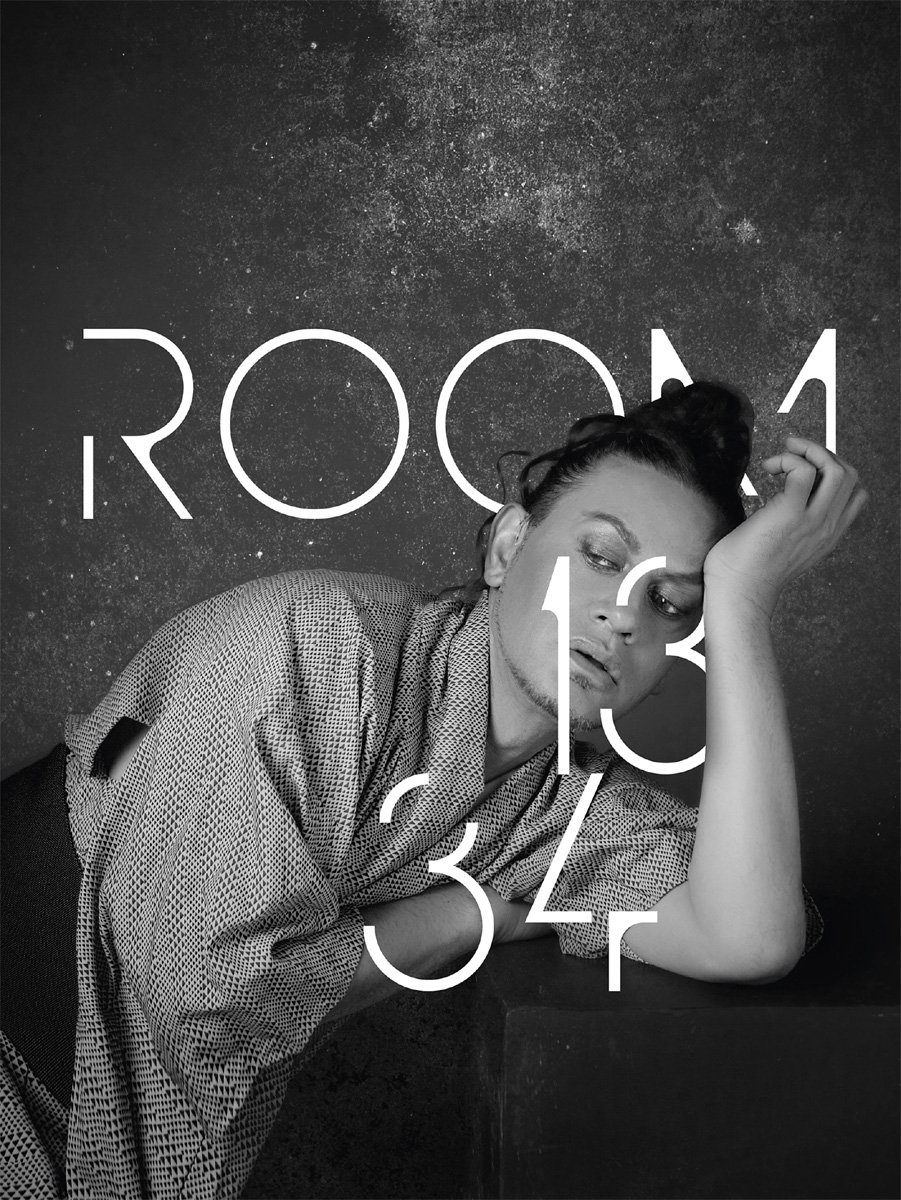

Poster for Room 1334, Auckland, 2015. Photo by Sara Orme; poster design by Zakk d’Larte.

But she also takes the opportunity to try again to divine Mika’s character. She begins with an observation – ‘It’s difficult to put a tag on Mika and, really, why would you try?’ – and adds:

Even finding words to describe what he is – and does – is difficult. He’s mercurial, unpredictable, impulsive, intuitive, capricious, eccentric – and all in a good way. He’s the consummate professional but try to praise him to his face for his artistry, his tireless work with young people and his development of emerging (primarily) Maori and Polynesian artists and he’ll wave you away with a flick of the hand and talk about the work.

In her review of Room 1334 she observes the way drive and discipline have been intertwined throughout Mika’s decades-long performance career. ‘[I]t’s always the work,’ she says. ‘He’s exhaustingly tireless, his output prodigious, but never, like some, at the expense of his unique artistry.’ In Matheson’s words:

It’s worth remembering that Mika has, for years, been at the forefront of developing a powerful and unique queer voice. It has its own comic style, its own delivery mechanics, its own tools for facing the world when you’re a minority within a minority and you can’t walk away from it; it has its very own, inimitable anger.

ZEITGEIST

What was once closeted or outré, after so much grief and hardship, now seems to have floated almost effortlessly to the surface of popular culture. Gay marriage is celebrated in New Zealand, in the USA, and increasingly in the world beyond. Dan Savage’s column on sex and sexuality has gone viral, and he’s now world famous even in New Zealand.21 The New York Times has recently featured a months-long series devoted to the stories of transgender people on its op-ed pages. Surely these are signs that the culture war has been won? But it’s not as simple as that. Nor is anyone so safe, given the rightward, so-called ‘populist’ turn, in the USA, the UK and elsewhere, as seen in the aftermath of Donald Trump’s election to the American presidency and the rapid roll-back of basic rights and freedoms. In his recent reflections on Susan Sontag’s ‘Notes on Camp’, avant-garde Canadian artist/writer Bruce LaBruce complains that camp has become unexceptional. Camp, he says, is now ‘a sensibility that has been appropriated by the mainstream, fetishized, commoditized, turned into a commodity fetish, and exploited by a hypercapitalist system, as Adorno warned’.22 He adds:

This new annexation and corruption of the camp sensibility now exists largely without the qualities of sophistication and secret signification that were developed out of necessity by the underground or outsider gay world, which originally created camp as a kind of gay signifying practice not unrelated to black signifying, or even black minstrelsy. It was developed as a secret language in order to identify oneself to like-minded or similarly closeted homosexuals, a shorthand of arcane and coded, almost kabbalistic references and practices developed in order to operate safely apart and without fear of detection from a conservative and conventional world that could be aggressively hostile towards homosexuals, particularly effeminate males and masculine females.

The 2014 Pride Parade, Auckland. Mika led the parade down Ponsonby Road with his tribe of queer kids. He is wearing a one-off Kiri Nathan ‘Caged Māori Temptress’ costume. Hair is by Vada. The kids are wearing costumes from the Mika Haka Torotoro show designed by Elizabeth Mitchell. Left to right: Ryan Turner, David Adams, Zakk d’Larte, Siche Zhang, Hannah Martin, Mika, Logan Kopa, Kevin Xia, Ben Hammond, Jay Tewake, Boyan and Azhar.

SXWS, Austin, Texas, 2015. J. Carr, Mika and Lamar Bbc Sanchez pose at the New Zealand SXSW party. ‘Perfect! BBQ in a tent and NZ wine!’

Mika in front of the sign at GayBiGayBi, SXSW, Austin, 2015, having just arrived on Ron English’s ‘POPaganda’ double-decker bus.

Things have changed, LaBruce says:

In the contemporary world, in which gays have largely assimilated into the dominant order, such signifying practices have become somewhat obsolete, and the previous forms of camping and camp identification have long since been emptied of camp or gay significance, rendering them easily co-opted, commercialized, and trivialized.

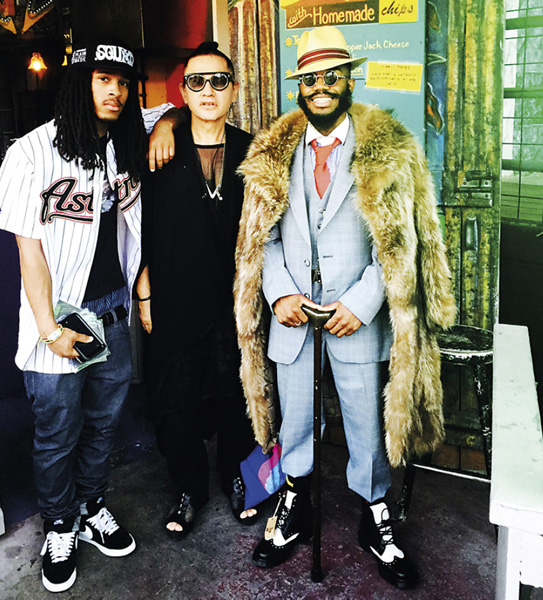

New York Fashion Week, 2013. Mika, Blake Diiamond, B. Hawk Snipes and Pow Jones in the front row. In the same week, Mika opened the New Zealand Showcase.

What he sees is a kind of ‘conservative camp’: ‘Sarah Palin, Newt Gingrich, Bill O’Reilly, Donald Trump and Herman Cain . . . enacting a kind of reactionary burlesque on the American political stage’. Somehow, almost impossibly, the dominant culture has sublimated its nemesis and now threatens to neutralise its voice in the ensuing cacophony, and so, he says,

The new tendency of conservative camp runs in diametrical opposition to the impulses of classic gay camp, which sought to celebrate, elevate, and even worship the qualities of deviance, difference and eccentricity that characterized the highly aestheticized homosexual experience of past eras.

HOT ENOUGH, BABY?

It’s a grey dawn. The corner of a corrugated metal door, covered with graffiti swirls, a swath of suburban street, houses and a car, a tree sparkling in early sunlight just beyond. The camera begins to move. The beat starts. A bright red high-heeled shoe taps. Close-up: a chest covered in fancy dress, orange and yellow feathers, black and red sequins, sways. A feathered headdress turns to the sun. Through a concrete drainage pipe we see, in sun-drenched silhouette, a figure – man? woman? – raise red feather and fringed arms to the sky as the camera zooms in. Is it a bird? Is it a drag queen? It’s Mika in full flight for his 2014 music video ‘Coffee’.23 The camera pulls right back, then races in as he turns: ‘What kind of coffee do you like?’ It’s less a question than an assertion. And it’s not really about coffee.

What kind of coffee do you like

Coffee black or coffee white

What kind of coffee do you like

The kind that keeps you up all night

‘Coffee’ music video shoot, 2014. Mika with Taki Māori in full swing at Ōtara Mall, Auckland. The song was written by Mika and Steve Robinson in 1992, and remixed by Siche Zhang for the 2014 YouTube release. Costumes were put together by Karlyn Cherrington from Mika’s container and archives. Director: Daniel Martin.

‘Coffee’ music video shoot, Clendon Mall, Manurewa, 2014. Left to right: Siche Zhang, Mika, Trina and Lauren.

His eyebrows are arched, his make-up pronounced. He starts strutting through a rapid series of cuts. He throws up a ‘talk to the hand’ hand at a woman who, mouth open with the momentum of the moment, tosses two cups of chips into the air; they fall in slow motion on either side of her upturned head. Taking her place, we see the hand and Mika in profile as he swans right, the sun glinting off cars in a car park. Stop! It’s time to party!

The beat goes on. Mika and the woman carry on, arm in arm down the sidewalk, singing together.

A cup of you in the morning

A cup of you in the night

Black, strong and percolated

Like my lover – just right

‘Coffee’ music video shoot, 2014. Mika and dog in Clendon Mall, Manurewa.

‘Coffee’ music video shoot, 2014. Mika and tribe head for the camera in Ōtara Mall.

From one shot to the next, he’s changing costumes – into and out of native drag – and accumulating a remarkably diverse crew. A kapa haka rōpū (troupe): men in piupiu with patu in full haka flight and women in korowai swinging poi. A ballerina in black leotard, pink tutu and toe shoes performing an arabesque, the kapa haka troupe visible still in the background as she leaps. A group of grey-haired men and women, smiling broadly, swinging and finger-clicking. Drag queens and club kids. Breakdancers performing acrobatic flips and spins. They are all virtuosic – distinctively, exuberantly, freely so.

Caffeine hit light my fire

Crema de crema o’ delight

Arabica, Costa Rica, Javanese, Braziliana

Constantly in motion himself, Mika repeatedly bursts through, raising his arms, summoning and celebrating, plunging forward.

‘Coffee’ music video shoot. Mika with Lennie Hill (cameraman) in Ōtara Mall.

‘Coffee’ music video shoot. Mika with Taki Māori. ‘Our kuia and kaumātua of Manurewa came down to support us and so of course we had to put them in the video.’ The warrior with the painted moko face, ferocious with his taiaha, is Damon Heke, who, along with his wife Kelz, led Taki Māori to Edinburgh that year. Damon passed away in 2017.

The video stutters. It’s night. Dark blueness and bright lights. Mika in his recent Pride Parade costume, an elaborate white and pastel construction complete with headdress, swingingly summons zombies out of the grass, their faces painted white, hair hanging, lurching and leering, dancing under his spell. Then cut back to the suburban street at dusk, the company still with him, zombies and all.

Coffee with cream’s gonna take me higher

Coffee supreme sets me on fire

Demitasse and mochaccino, Turkish black and cappuccino

Just can’t control my espresso desire.

Bridge: An interlude with Hannah Martin, sexy and sultry in a brightly lit tinsel shower, undulating, swinging her hair and pouting:

Hey baby

Whatcha feelin’?

Care for a latte

Long black

Is this hot enough, baby?

French style . . .

Back to the street for another chorus. A thunderclap. Silence. The crowd holds. Mika is handed a white demitasse by a subservient, bowing blond boy. Crickets. He sips, sneers, grins, glints and las ci viously licks his lips. He tosses the cup. Cross to a street party under bright lamps, Mika in gold lamé this time – his Pō costume, including the long wings and soft sculpture crown. The company dances, every which way, and the video also: shots multiply and bounce, recapping and reflecting. It’s fully ecstatic until someone pulls the plug. Blackout. Then it’s the morning after, in black and white. Mika wakes smeared and dishevelled, discovers a bright-eyed zombie (Jay Tewake) in his bed. The zombie grins, raises his coffee mug to toast us and nods as the camera closes in on his face, and the beat begins again.

MIKA’S MIRROR BALL STAGE

It’s not so much that there are two New Zealands, as that the one we have isn’t so singular as it generally appears (or is made to appear). A mirror ball starts as a whole flat thing, is curved, broken into pieces, and then tacked together eccentrically, creating odd joints, fissures and fractures. It spins and, when light is projected onto it, we can – if we look – see ourselves as/in sparkling bits, prismatic, circling alongside one another, still connected (if obliquely) and spinning freely regardless. New Zealand culture may itself be a bricolage – loosely pieced together from the shiny and not-so-shiny bits and pieces of the world around us, starting with the mixture of Māori and British moving through an intense period of Americanisation and on to just about everywhere else. With mediatisation and globalisation, the fragments of culture we attach to ourselves become ever smaller, more itsy and bitsy, but when we dance they flow together and we become whole – at least for the duration, until we again take our seats at the sidelines.

In his Aroha Mardi Gras performance, Mika badgers the audience to get up and dance, and then, when they hesitate, he tells them ‘you’re too late’ and orders them to sit again. He’s not patient that way. When he finds at-risk young people (and a few of us not-so-young) and makes a space for them to make lives for themselves, he doesn’t do it nicely. He says ‘I see you’ and he also says ‘you’ll have to work at this, make for yourself a (beautiful, tough) skin . . .’ It’s not magic. It’s discipline first, then the joy of something like vir tuosity – of vitality. Mika invites us to rummage around in our closets (pun intended) and to fashion ourselves with what we find there, to make our own party dresses from the fabrics of our pasts, of our aspirations, of the communities to which we belong. Like the only gay brown boy who found himself in the 1970s at Timaru Boys’ High, we are to be, if not entirely fearless, then fully fierce . . . and fabulous.

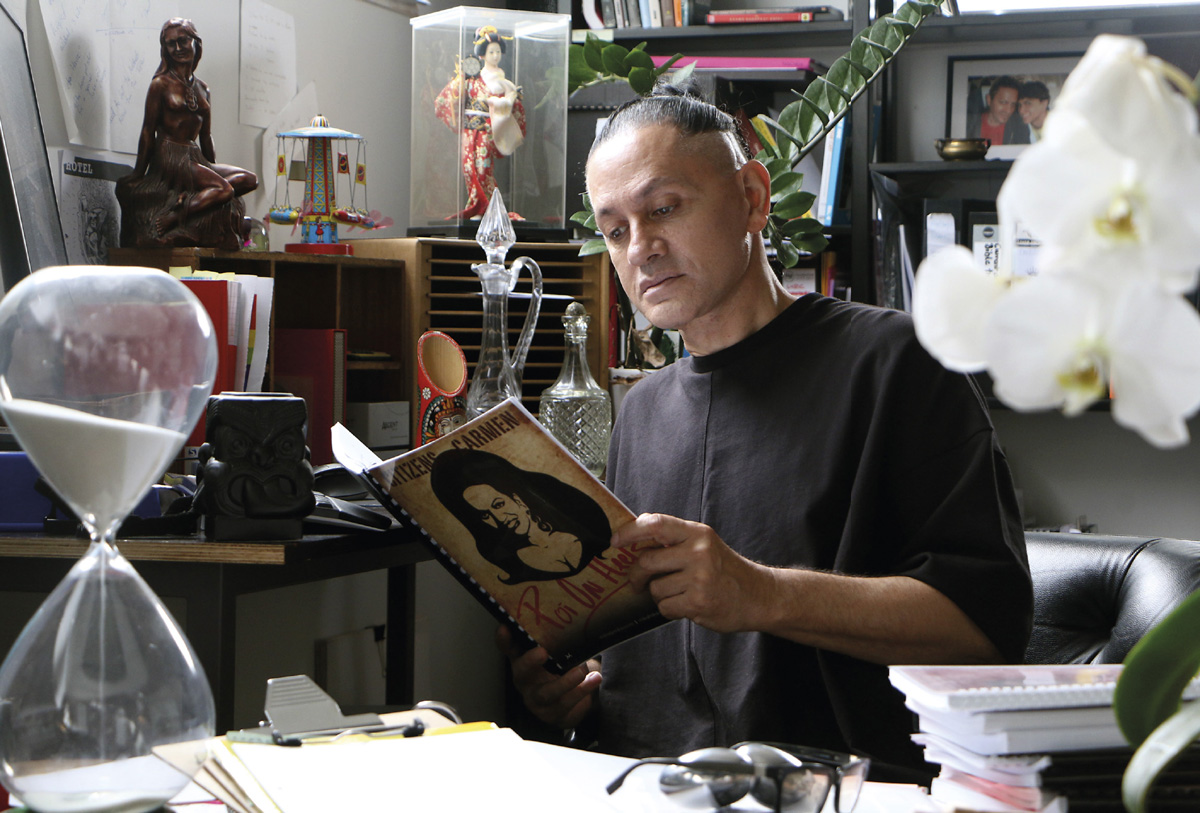

Mika at work in his studio, March 2018. Photo by Jay Tewake.

What I want, always, is to be an artist.

— Mika