5

Enslaved Agricultural Labor at Mount Vernon

When Washington returned from a meeting of the Potomac Company in July 1786, he rode immediately to the fields where he could observe the wheat harvest just underway. Before reaching the Mansion House for breakfast, he counted at Muddy Hole Plantation six cradlers at work, including the enslaved overseer Will, and Tom, a cooper who usually worked at the mill. With them was Jack, a field laborer from Dogue Run, “who tho’ newly entered, made a very good hand; and gave hopes of being an excellent Cradler.” At Ferry Plantation, Boatswain and the postilion Joe, both from the Home House, worked as cradlers with Caesar. Over the next ten days, Washington made daily visits to the plantations to monitor the progress of the harvest and to assess the work of individual laborers. He took special note of those who left their usual work to assist in the harvest while the wheat was ripe and the weather clear. At River Plantation, he watched Tom Davis, an enslaved bricklayer, “who had never cut before, and made rather an awkward hand of it.” Two women from the Home House, Myrtilla and Dolshy, worked with the combined gangs from Muddy Hole and Dogue Run to complete the harvest at the first plantation and then the other. A group of young boys and girls who had never worked in the fields before assisted in making hay after two hired white men cut the grass under the direction of James Bloxham. Upon the completion of the harvests at the Ferry and River plantations, Washington “Gave the People employed in it the remainder of the day for them selves.” It was a rare respite in the increasingly rigid work schedule he imposed.1

As soon as the season’s grain harvest was finished, Washington compiled a list of changes he intended to introduce for the following year. His first objective was to make the enslaved laborers at each plantation carry out the harvest by themselves, without help from elsewhere on the estate and without hired white laborers. Washington believed he could accomplish that goal by prescribing an exact sequence of cradling, raking, and binding based on his observations. Cradling would begin earlier to allow a smoother cut and time for the straw to cure for two days before it was raked and gathered. For every two cradlers, Washington would assign four rakers and one binder. The children, he concluded, would be competent to carry the bundles. He expected these changes to have the effect that the work “will be done with more ease, regularity and dispatch, because it becomes a sober settled work—there being no pretext for hurrying at one time, and standing at another.” By making each raker follow a single path, “the authors of bad work may be discovered and every person marked.” Washington further intended to eliminate any possibility for time not spent on productive work. If the enslaved laborers remained on their assigned plantations, with their tools at hand, they would be prepared to undertake other work if weather interrupted the harvest. Washington envisioned days filled with the regular and deliberate work he prescribed for the enslaved field laborers, and he spent much of the next few years devising ways to extend that “sober settled work” throughout the agricultural calendar. He also resolved to rely more exclusively on the enslaved laborers he owned, finding ways for them to perform all the varied tasks of the more complicated system of farming.2

Under the new farming regimen, work for the following season began almost as soon as the wheat harvest was over. Sometimes as early as August and continuing into October, field laborers sowed the wheat that would be harvested the following summer. The threshing of wheat could wait until winter or even spring, but that used for seed needed to be threshed and cleaned before fall. The sowing of rye and timothy coincided with that of wheat. Much of the fall was spent gathering and processing the other grains grown over the summer. The field laborers at each plantation hauled rye and oats to barns where they cleaned the grains. Corn required substantial labor at every stage of its cultivation, and in late fall and early winter, the husking of corn frequently brought “hands gathering” for the work. Usually in late December, a group of enslaved men butchered hogs for the meat that was distributed to the overseers and used by the Washington family. In 1786, over a hundred hogs were slaughtered.3

During the winter months, the field laborers spent much of their time constructing or repairing the fences that divided fields and separated the meadows and pastures. The increased number of livestock, particularly the draft animals that pulled the plows and harrows, created more need to assemble and relocate pens. If the ground was not frozen, field laborers in January grubbed in the swamp land, pulling up roots and stumps to prepare it for cultivation, and broke up the ground in the fields. By February, weather permitting, plows were running everywhere. Winter was also the season for field laborers to gather dung and then cart it for scattering in the fields. When snow or cold prevented work in the fields, the laborers dressed the flax used by weavers making clothes for all the estate’s enslaved laborers and their families. Threshing wheat continued in February and March.

In early spring, the field laborers worked more regularly to clear and to break up ground for the plows. The sowers put in oats as one of the earliest crops, followed by fodder grasses and barley in early April. Men and women drove the plows and then crossed the fields of oats with harrows. By late April, they were planting corn, some of it in the traditional practice of hilling, but increasingly sowed with the drill plows constructed by the carpenters and smiths on the estate. When corn was planted in rows with the drill plows, sowers returned to plant potatoes and carrots between the rows, in a practice Washington thought would reduce the erosion associated with corn. Later they sowed turnips. Once the crops were growing, the field laborers began weeding with hoes, and in some of the cornfields the plow drivers turned the soil between rows. June frequently brought hurried tasks so that all field laborers would be available for the harvest that began with hay crops and continued with wheat. July was also the harvest time for flax and rye. Some years the plow drivers turned the buckwheat into the soil as a green manure; other years the field laborers harvested it as a fodder crop.

Throughout the year, the essential work of preparing the ground and cultivating crops fell to the field laborers whom Washington designated “hoe people.” Washington regarded their labor as particularly onerous and undesirable, as evidenced by his threat to make a bricklayer “a common hoe negro” if he did not improve his work. He made a similar threat to send a group of seamstresses at the Mansion House to work as “common laborers” under the overseers at the plantations if they did not increase the pace of their shirt making. The majority of the “hoe people” were women, and when Washington recorded their work he seldom referred to them by name. He clearly knew them as individuals and named them when they were sick or gave birth, but in the record of their routine work the enslaved women in the fields remained largely anonymous. The women field laborers often worked together in small groups, occasionally with one enslaved man directing their tasks. The adoption of British husbandry and the introduction of more sophisticated farm implements did little to relieve the drudgery and physical burden of those who still worked with hoes. Outside the growing season, much of their time was spent clearing and grubbing fields to prepare the soil for plowing. They were consigned to monotonous tasks like cutting down corn stalks. While the men prepared posts and cut tenons in rails, the women used the framing to construct fences.4

Women were more likely than men to work spreading dung in the fields, and in late winter months they often filled gullies with brush and corn stalks to halt further erosion. Although men worked in most of the tasks associated with the diversification of farming, such as sowing and mowing, the most challenging new task for the women was to join with the men in plowing and harrowing with draft animals. After childbirth, an enslaved woman typically returned to the fields in less than a month. Although able to stop work to care for their sick children, women were no more likely than men to be listed in the weekly reports as sick themselves.5

The work of the field laborers depended on that of the enslaved carpenters, ditchers, and spinners. In the spring of 1786, before the harvest Washington monitored so closely, Isaac and three other carpenters manufactured many of the implements used to gather the wheat. They made new rakes and cradles, and mended others. They fixed sneads, or handles, to the scythes. They also constructed harrows, likely based on the drawings Washington traced from his edition of Lord Kames’s The Gentleman Farmer. Over the next several years, the carpenters regularly constructed plows, carts, and axletrees. They made nine-foot rake handles and plow beams, using ash cut for the purpose from the estate’s woods. After 1789, the enslaved carpenters worked with the hired joiners, or house carpenters, in the construction of the great agricultural structures, like the barn at the Ferry and French’s plantations, while they continued to produce many of the implements used in fieldwork.6

The ditchers made possible the division of fields for the system of crop rotations, and they maintained the boundaries at each plantation. Ditching was skilled work for which Washington had previously hired white men. After a white ditcher, the indentured servant Daniel Overdonck, left Mount Vernon in late 1788, the enslaved ditchers who had trained under him became a dedicated corps of five or six men working across all the plantations and at the mill as needed. Under the supervision of the Mansion House overseer, they drained swampland for the creation of arable fields and meadows. They maintained the millrace and dug the ditches that separated other fields. Washington considered their work “a kind of trade” that he could employ across the estate, and he exempted the ditchers from his expectation that enslaved laborers work only on the plantation where they resided.7

The spinners and seamstresses on the estate, often working with a hired tailor, were by the mid-1780s able to produce much of the clothing worn by the enslaved field laborers and artisans. What had once been purchased from Great Britain or Philadelphia was now fabricated largely from the wool and flax produced on the estate. In 1786, field laborers received a spring distribution of coats, breeches, shirts, and trousers, and for the women, a summer “petty coat.” In November they received one pair of shoes and stockings. Most of the spinners and seamstresses were enslaved women, although they were often joined by men who were incapable of work in the field.8

Despite Washington’s recurrent attempts to make each plantation self-sufficient in labor, the annual harvest of grains and hay still drew artisans away from their workshops and to the fields. The harvest remained a group activity that interrupted the focused tasks that characterized labor during most of the year. As Washington reminded a farm manager, “Hay time & Harvest will not wait, and is of the highest importance to me, every thing else must yield to them.” Carpenters were the most frequent additions to the force of field laborers at harvest, but ditchers, bricklayers, and spinners also joined in the work. Washington supervised all of them, sometimes visiting each plantation twice a day at the busiest time of a harvest. The annual harvests of hay and grains coincided with intense work in other fields, as plow drivers prepared soil for the sowing of the next season’s wheat, and other crops at the height of the summer required regular weeding by plow drivers and hoe workers. While in the fields, Washington frequently reallocated labor in response to weather conditions or the urgency of the work, and he, rather than an overseer, directly commanded the field laborers to shift from one task to another. During the harvest of 1788, when he was perhaps more closely involved than ever before or after, Washington noted that “I ordered the People” to different work or to a different plantation. Although he never recorded the independent decisions of the laborers, the complexity of sequencing the tasks and the variety of simultaneous work at each plantation would have depended on the self-management of experienced field laborers.9

Washington was largely successful in finding steady if not settled year-round work for the enslaved laborers he controlled. This was particularly true during the first several years of the new course of farming, when the demand for more arable land and the intense cultivation required to restore the soil placed an enormous burden on the field laborers. Over the next decade, the regular experiments and the introduction of new crops provided challenging work for the able workers among a steadily increasing enslaved population at Mount Vernon. The laborers were engaged in the frequently shifting work that blended new cultivation practices with the physical burden of preparing and maintaining the soil. Their work was alleviated only by the significant increase in the use of draft animals for plowing, harrowing, and carting, and by the customary rest on Sundays, at Christmas, and again on Easter and Whit Mondays.

Throughout these new seasonal routines of work, Washington was a daily presence on the plantations, and his personal supervision brought him into even more frequent interaction with individual laborers. A Scottish visitor who accompanied Washington on his daily circuit of the working plantations reported in the fall of 1785 that Washington “strips off his coat and labors like a common man.” Washington, to be sure, was not assisting the field laborers in their work, but he was determined to understand the practical tasks of the field and to impart to the enslaved laborers his presumed knowledge of cultivation. Over the next few years, he took every opportunity to be with the field laborers, whom he frequently called “my people,” as they carried out new and often experimental tasks.10

The cultivation of the land by enslaved agricultural laborers was for Washington the most salient characteristic of farming on his plantations, and he identified the management of the enslaved laborers as the most significant challenge to the successful adoption of the model of British husbandry that drove his reorganization of the estate. He believed each task of cultivation, each experiment in new crops, and each application of new farming implements needed to be incorporated within a system of supervision and enforcement for which no British agricultural treatise would offer guidance. The reliance on enslaved labor differentiated Washington not only from the practitioners of improved husbandry in Great Britain, but also from a broader community of enlightenment leaders with whom he shared visions of a new era of harmony among nations throughout the Atlantic world. At the same time that Washington undertook his comprehensive efforts to extract more labor and greater efficiency from the enslaved, he confronted a new and growing antislavery movement, often advocated by individuals on either side of the Atlantic who simultaneously celebrated him as the champion of American independence. On the eve of Washington’s return to Mount Vernon, Lafayette and William Gordon urged him to free the slaves he owned as the culminating act in his defense of the revolutionary ideals of liberty. Other prominent antislavery leaders, including many who knew him only as the public hero, turned directly to Washington to set a powerful and personal example by endorsing abolition and by manumitting the slaves he owned, and these appeals surrounded him as he reassessed the management of enslaved labor on his estate. Even as a private farmer, Washington could not escape the antislavery expectations placed uniquely on him.

In retirement at his estate, Washington received a succession of appeals from antislavery advocates who asked for his endorsement of some form of abolition. A Massachusetts merchant, recently back from London, visited Mount Vernon in January 1785 and delivered a set of abolitionist publications authored by the British antislavery leader, Granville Sharp, who personally requested that the pamphlets be presented to Washington. In May 1785 Washington met at Mount Vernon with the British Methodist leaders, Thomas Coke and Francis Asbury, who solicited his support for a petition calling on the Virginia General Assembly to enact a general emancipation. According to Coke, Washington explained that he had shared with the leading men of his state his support for the principle of their cause, but he declined to sign the petition. He indicated to the Methodist clergy that if the assembly took the petition under consideration, he would present his support by letter. Several months later, James Madison, a member of the assembly, informed Washington that although several prominent members professed support for the petition, the assembly rejected it without debate, thereby eliminating any possible call for Washington’s public comment.11

That Washington was a slaveholder as well as the hero of the Revolutionary War made him all the more compelling an object of the abolitionists’ appeals. After the failure of the antislavery petition in Virginia, Robert Pleasants called on Washington to extend to the slaves under his ownership the same “Liberty and the Rights of Mankind” that had been the cause of the Continental Army. Pleasants, a Quaker plantation owner in Henrico County, Virginia, who had freed and then hired the slaves on his estate, called attention to the paradox, if not outright hypocrisy, of those who fought for the cause of liberty and now sit down “in a state of ease, dissipation and extravigance on the labour of Slaves.” He speculated that Washington’s continued ownership of slaves resulted from a mix of habit and racial prejudice, but he stressed the urgency of emancipation, which he described as a sacrifice that “the Lord is requiring of this Generation.” Washington as “the Successful Champion of American Liberty” had a unique opportunity to crown all his earlier military achievements with support of abolition. “Thy example & influence at this time, towards a general emancipation, would be as productive of real happiness to mankind, as thy Sword may have been.” Washington made no known response to Pleasants, but he filed the letter among his papers.12

In private correspondence, Washington in the spring of 1786 reiterated his support for gradual abolition enacted by a state legislature. He assured Philadelphia merchant Robert Morris that on the subject of slavery “there is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do, to see a plan adopted for the abolition of it—but there is only one proper and effectual mode by which it can be accomplished, & that is by Legislative authority: and this, as far as my suffrage will go, shall never be wanting.” In reply to Lafayette’s announcement of his own recent efforts in support of abolition, Washington wrote, “Would to God a like spirit would diffuse itself generally into the minds of the people of this country.” With the failure of the petition to the Virginia Assembly, Washington despaired of seeing that spirit, but he assured Lafayette of his support for gradual abolition, carried out by legislative authority.13

No public pronouncement in favor of abolition followed these private assertions in 1786 or at any later moment in Washington’s life. Washington was scarcely alone among Virginia slaveholders who voiced support for the principle of abolition and then declined to offer any public encouragement for antislavery legislation. He professed support for abolition, however, at the same time that he increased his reliance on enslaved laborers in every aspect of the new and complicated course of British husbandry he was establishing at Mount Vernon. Nothing in his organization of the labor force or in his new methods of supervision indicated any expectation of changes in the status of the enslaved.

Nor did Washington ever explicitly link any modifications in his own management of enslaved labor to his exposure to antislavery arguments. But in the years following the Revolutionary War he adopted a management system that differed in principle and practice from his organization of enslaved labor before the war. Only incidentally, over the course of the first several years of his new farming initiatives, did Washington reveal several resolutions to mitigate what he perceived to be the most brutal and inhumane aspects of the institution of slavery. He also demonstrated a heightened, self-conscious concern with protecting his reputation as a slaveholder. Without any apparent knowledge of similar developments in the Caribbean, Washington quietly adopted practices associated with the amelioration movement, by which planters sought to make slavery more efficient, more humane, and more easily adapted to British models of agricultural improvement.

When amelioration efforts appeared on plantations of the British Caribbean beginning in the 1770s, some planters explained their new focus on improving working conditions and diet explicitly in terms of the financial advantages to be gained by reducing sickness and mortality among the enslaved. For others, however, such as Joshua Steele in Barbados, amelioration of the condition of the enslaved was a frankly humanitarian effort that anticipated some form of gradual abolition. A small number of Chesapeake planters adopted comparable changes in management in response to similar impulses rather than as a result of any direct influence of the Caribbean examples. In Virginia and Maryland, where mortality was significantly lower than in the Caribbean and the enslaved population was growing by natural increase, the changes in slave management were more likely to reflect humanitarian sentiments or self-professed benevolence. For some, including Washington, amelioration efforts represented mixed and even contradictory intentions to make slavery function more efficiently while demonstrating the enlightenment of the landholder in the face of a rising critique of slavery. Amelioration in the Chesapeake as well as the Caribbean frequently merged with the adoption of agricultural improvement. Jefferson after his return from France resolved to make the management of slaves more “rational and humane” at the same time that he adopted the program of agricultural improvement he learned about from Washington and others. Across the range of ameliorative changes adopted by planters both sympathetic and hostile to antislavery arguments were common efforts to make enslaved labor more efficient and to replace coercive force with persuasion and incentives.14

Among the deliberate changes Washington made in managing the growing number of enslaved people under his control were decisions to end all participation in the commercial slave trade, to protect slave marriages and families, to provide adequate food and medical care, and to restrict violent punishment. Washington believed that by fixing these minimal conditions on their treatment, he could establish a kind of transactional relationship through which he expected the enslaved to provide him with their labor in return. The new terms of managing enslaved laborers were a critical part of what Washington hoped to demonstrate through the implementation of a new course of farming on a Virginia estate, and he initially believed his new system of supervising labor would be a further demonstration of his enlightenment.

Following his return to Mount Vernon, Washington, who steadily purchased slaves up until 1775, was reluctant to participate in any commercial exchange of slaves, even expressing a “great repugnance to encreasing my Slaves by purchase.” During the Revolutionary War, he thought the sale of slaves might be a first step toward fulfilling his wish “to get quit of Negroes,” but by 1785 he was as reluctant to sell as to purchase any slaves. (His only purchase of slaves after 1785 was intended to relieve the financial burden of a relative rather than to gain a new source of labor. In 1788, Washington agreed to purchase thirty-three slaves valued at more than £1300 from the estate of his late brother-in-law, Bartholomew Dandridge, which remained in debt for a loan made by Martha Custis in 1758. Washington left all of the slaves in the possession of Dandridge’s widow and exercised almost no role in the management of the laborers.) Washington, however, was so deeply invested in slavery and so frequently involved in commercial transactions with other slaveholders that he faced several decisions that challenged his determination to end his purchase or sale of slaves.15

In 1785, as he prepared to rent his settled lands in western Pennsylvania, Washington wanted to avoid any sales or transfers counter to the wishes of the enslaved persons who remained on his lands. (He never mentioned the option of manumission, by then legal in Pennsylvania and Virginia.) Washington’s preference was to bring the enslaved individuals to Mount Vernon, but only “if the measure can be reconciled to them.” He reminded his Pennsylvania agent, Thomas Freeman, that Simon’s African countrymen and Nancy’s family would be glad to see them back at Mount Vernon, and he promised to employ Simon as a carpenter alongside his shipmate, Sambo. If Simon or Nancy, the only ones originally from Mount Vernon, or any of the other slaves declined to relocate to his estate, Washington told his agent he would “not suffer them to go down the river, or to any distance where you can not have an eye over them.” None chose to move to Virginia, even though it meant sale to new owners. After Freeman sold the nine individuals to five different buyers, he informed Washington that he would “not have Sold the Negroes but they would not be Prevailed with to come down from any Argument I could use.” The sale also exposed Washington for the first time to the impact of the Pennsylvania Abolition Act of 1780. Freeman reported that the enslaved girl Dorcas, for whom he expected to receive £30, sold for less than half that amount because, under the terms of the act, she would be free at the age of twenty-eight.16

Although he stated his aversion to acquiring slaves by purchase, Washington was willing to make an exception if he could gain the skilled labor he wanted for his new course of farming. In 1786 he seriously considered accepting slaves as a payment on the long-delinquent debt owed by the Mercer family, and in his negotiations with John Francis Mercer, Washington agreed to accept six or more slaves, provided they were all men who could carry out specialized work. He wanted to employ three or four as ditchers at a time when he was still hiring white ditchers to direct the work and to instruct enslaved men on the estate. He agreed to accept the same number of enslaved men to work as artisans. Washington further stipulated that the designated individuals must be healthy “and none of them addicted to running away.” In his strict calculation of labor needs and with a disregard for the potential disruption of family connections, Washington insisted “women, or Children, would not suit my purposes on any terms.” Mercer prepared for Washington a list of all the enslaved laborers he would offer, with detailed descriptions of their skills, family connections, and appraised market values. Mercer also noted his reluctance to divide families “which have long continued together,” but would do so if necessary. To accommodate Washington’s preference, Mercer added to the list the names of six enslaved men, and it was those individuals whom Washington agreed to accept, as long as the younger ones were ready to learn a trade from the white artisans hired for the purpose. After Mercer offered other means of repayment in lieu of the slaves, Washington readily agreed. “The money will be infinitely more agreeable to me than property of that sort,” but he also left open the possibility of procuring the slaves on more favorable terms “if I should want any of those people.”17

While again insisting he was opposed in principle to the purchase of additional slaves, Washington in 1787 authorized Henry Lee to buy for him an enslaved bricklayer recently advertised for sale. If the man proved to be “in the vigour of life” and a good worker, Washington had much work for him in the construction of his new barns. He had no interest in the purchase if the man had a family that came with him or from whom he was reluctant to separate. John Lawson of Dumfries, not Lee, purchased the enslaved bricklayer, Neptune, whom he then agreed to sell to Washington. Neptune, however, protested the sale and relocation that would separate him from his wife, who lived on a neighboring plantation. After Lawson persuaded Neptune that Washington would permit him to visit his wife, Neptune arrived at Mount Vernon in April 1787. Although Neptune did “not profess to be a workman,” Washington found he had enough knowledge of bricklaying to learn the trade, but when he told Neptune he planned to purchase him, Neptune seemed “a good deal disconcerted” because of the separation from his wife. Washington complained to Lawson of his own embarrassment, “as I am unwilling to hurt the feelings of any one.” Neptune soon presented himself before Lawson at Dumfries, twenty miles from Mount Vernon. He acknowledged that he had left Mount Vernon to avoid being sold so far away from his wife, but that he would agree to be hired to Washington. Neptune then delivered to Washington the letter explaining Lawson’s proposed terms of hire.18

Although Washington may not have hired Neptune (no further record of him survives), the discussions with the enslaved bricklayer revealed how the ties of marriage and family provided the enslaved with the most powerful means to exert some limited influence over the conditions of work and their place of residence. Washington rejected a merchant’s proposed exchange of slaves from Mount Vernon because he did not believe “it would be agreeable to their inclinations to leave their Connexions here, and it is inconsistent with my feelings to compel them.” He agreed to keep Peter Hardiman, the enslaved stable worker owned by David Stuart, because Hardiman seemed unwilling to leave his wife and children. At the death of his mother, Mary Ball Washington, Washington offered to accept ownership of an enslaved man long resident at Mount Vernon, even though he deemed his monetary value far below other slaves in his mother’s estate. “I shall readily allow the difference, in order that the fellow may be gratified, as he never would consent to go from me.” On other occasions, Washington surrendered claims to slave property or debt repayment if he thought the transaction would force a sale or family separation.19

Fig 5.1 Edward Savage, “The East Front of Mount Vernon,” c. 1787–1792. Savage’s sweeping view sets the Mansion House in the context of the working estate, with a rare view of a residence for enslaved laborers to the right. The House for Families was constructed in the 1760s and razed in the early 1790s, when families of the enslaved moved to new quarters behind the greenhouse. Courtesy of Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association.

Washington’s professed regard for family connections, however, did not protect the family units of enslaved laborers on his estate. By 1799, over 70 percent of the individuals recognized as married in the estate records lived apart from their spouses, on separate farms, often at a distance of several miles from one another. Children of these marriages usually lived apart from their fathers, who were more likely to work and live at the Mansion House, where the workshops were located. Washington permitted visits only on Sundays, and, with limited success, he ordered overseers to prevent nighttime visits during the week. Although in his effort to prevent theft he instructed his manager to “absolutely forbid the Slaves of others resorting to the Mansion house,” Washington made an exception for those “as have wives or husbands there.”20

Prompted, as he said, “by motives of Justice,” but equally concerned with his own reputation as well as the deterrence of theft, Washington insisted that the enslaved be provided with adequate food. He expected his farm managers to determine exactly what amounts of corn meal the enslaved families needed, explaining that his “wish & desire is that they should have as much as they can eat without waste and no more.” On a visit to Mount Vernon during his presidency, Washington received repeated complaints from individual slaves who reported that changes in the distribution of food left many hungry. Washington also suspected that the overseers failed to distribute the full rations. He ordered his farm manager to distribute sufficient food, whether it be a peck or a bushel of corn a week. “In most explicit language I desire they may have a plenty; for I will not have my feelings again hurt with Complaints of this sort, nor lye under the imputation of starving my Negros and thereby driving them to the necessity of thieving to supply the deficiency.” At hearing the reports of want, Washington initially suspected that some of the enslaved were stealing corn to feed the poultry they kept in the quarters or to share “with strange Negros,” but he accepted the assurances of the enslaved overseer Davy Gray that the new ration was inadequate. At Dogue Run and Union farms, Washington heard further complaints, “which altogether hurt my feelings too much to suffer this matter to go on without a remedy.” The following year he received complaints from enslaved laborers who had not received their usual allotments of fish and who hinted that one of the white overseers, Hiland Crow, had surreptitiously sold the provisions. Rather than investigate the overseer, Washington limited access to the storehouse to a single individual who would distribute the fish to each farm.21

Although he acknowledged that the practice was falling out of favor among other improving estate owners, Washington continued to distribute liquor to the laborers during harvest, “as my people have always been accustomed to it.” He instructed his manager to be sparing in the allotment of spirits when the cost increased in the 1790s, but rum and whiskey were part of special tasks throughout the year. In the harvest of 1786, each of the plantations received gallons of rum along with one hundred pounds of beef from a cow butchered for the purpose of feeding the workers while in the field. When the fishery was in operation each spring, the laborers working there received multiple deliveries of rum, and, one year, whiskey drawn from a thirty-two-gallon barrel purchased in Alexandria. Rum was available to those butchering hogs during the Christmas holiday, and throughout the year, the enslaved received rum when they were sent to Alexandria for deliveries by boat.22

The provision of adequate food was the most basic obligation that Washington believed he owed the enslaved, followed by medical care. The written agreements with overseers required them to “be very careful of the Negroes in sickness,” and to distribute sweet milk to sick persons and children. In medical care, as in so many other matters, Washington suspected the negligence of the white overseers, whom he accused of ignoring illness and injury in those under their supervision. He wrote one manager: “I am sorry to observe that the generality of them, view these poor creatures in scarcely any other light than they do a draught horse or Ox; neglecting them as much when they are unable to work; instead of comforting & nursing them when they lye on a sick bed.” The burden for ensuring medical care fell then on the managers, whom Washington expected to discern with a heartless precision when a doctor’s attendance was necessary. In Washington’s estimation, if the call came too late, “in the last stage of the complaint it is unavailing to do it. It is incurring an expence for nothing.” Just as he thought the manager could determine the precise amount of food needed by the enslaved, and provide not “an oz. of Meal more,” so Washington expected the managers to uncover illness that was feigned as carefully as they determined when it was life threatening. He reminded William Pearce that he never wanted the enslaved to work when “they are really sick, or unfit for it,” but he warned Pearce to investigate complaints of illness that might instead be the effect of fatigue from traveling about the estate at night.23

The instruction that Whitting must deliver to the slaves “every thing that is proper for them” reflected Washington’s belief that he had, with his provisions and protections, established mutual responsibilities for both slaveholder and slave. The presentation of the work reports in the form of financial ledgers was the very embodiment of Washington’s conviction that the enslaved and the enslaver owed each other something, and the slaves’ side of the ledger could not be balanced until it accounted for every day of their labor. As he later explained his management of the enslaved, “it has always been my aim to feed & cloath them well, & to be careful of them in sickness; in return, I expect such labour as they ought to render.” Washington defined the labor he expected in return as a duty of the enslaved. He expected the managers and overseers to see that “my people can be brought into good habits, & a regular discharge of their duty.” He wanted the hired head of the carpenters “to make the hands entrusted to his charge, do their duty properly.” What Washington defined as a duty of the enslaved required “that, every labourer (male or female) does as much in the 24 hours as their strength, without endangering their health, or constitution, will allow of.”24

On at least one occasion, Washington compared the costs of the provisions distributed to the enslaved and the value of their labor. When he agreed in 1786 to hire enslaved laborers from Penelope French as part of the terms of a land purchase from her, Washington drafted a memorandum detailing the provisions he distributed annually to the enslaved laborers and their children. To clothe ten adults, Washington would provide sixty ells of coarse linen, fifty yards of cotton, one pair of shoes and socks for each adult, and five blankets among them. The thirteen children would receive clothing valued at between one-third and one-half that distributed to the adults. For the twenty-three individuals hired from French, Washington projected an annual allotment of three barrels of corn per person, ten barrels of salted fish to be shared by all, meat “now and then,” and occasional distributions of milk and fat. He anticipated the need for a doctor to attend the enslaved about six times a year, and for the services of a midwife at least twice a year. Washington paid county taxes of twenty shillings on each enslaved adult and ten shillings on each child. He estimated the cost of farming implements for each adult field laborer at £1 per year. Washington balanced the estimated costs of the provisions and equipment against the projected yield of cash crops, with eighty acres devoted to corn “for a gang chiefly composed of breeding women,” and eighty acres in wheat. As long as he paid the additional rent to French, he expected to lose money on his operation of the new plantation. As with any purchase or extended hire of laborers, Washington stood to gain from any births by the enslaved women. Several years after he first hired the slaves of French, he explained that “the chance of the increase of the Negroes, & consequently their work, was placed against the decrease; & no deaths have happened, whilst five or Six are not of full size for half sharers.”25

The overseer’s account book for 1786, the first full year of the new system of farming, measured costs of food and clothing by the market values of what was consumed at each plantation, even though almost all of these goods were produced at Mount Vernon. In addition to what was distributed directly to the enslaved overseers, each plantation received roughly one thousand herring per person and slightly more than three barrels of corn per person. The account book recorded the market value of clothing, most of it also produced on the estate, and the costs of tools and supplies from the estate’s store and of seeds purchased for sowing that year. The expenses for each plantation included the taxes paid on the number of tithables and, for the parish levies, the number of children as well as adults. Each plantation was debited for the value of the smiths’ and carpenters’ work, including the value of the carpenters’ days spent in the harvest. The accounts thus monetized the value of the work of these artisans who were not a part of the labor force of the respective plantation, although none of these individuals was hired, and no monies exchanged. On the credit side, only some of the crops produced and livestock sold were recorded, although accounts recorded the monetary value of commodities, such as wool and fodder crops, which were used on the estate rather than sold on the market. These accounts and the broader range of records suggest Washington relied on an estimation of market values of labor, provisions, and farm supplies to measure the effectiveness of his allocation of artisans across the estate. For the most part, the extensive, labor-related records initiated after 1785 focused on what, in Washington’s mind, the enslaver and the enslaved owed one another.26

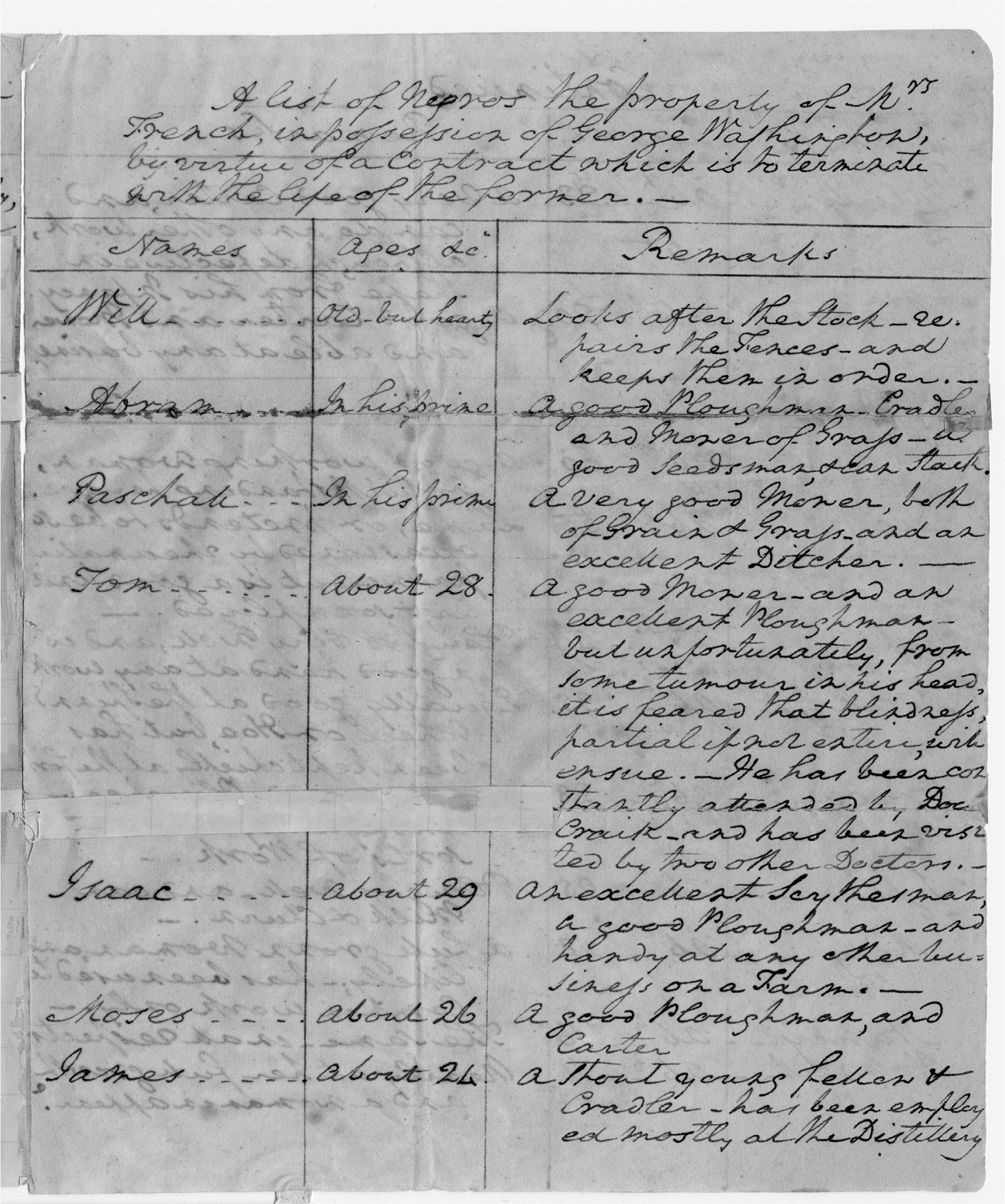

Fig 5.2 “A list of Negros the property of Mrs. French, in possession of George Washington” (excerpt). In the summer of 1799, Washington compiled a list of the forty enslaved persons whom he leased from his neighbor Penelope French and now proposed to return. In his description of the adults, Washington offered his most detailed assessment of the laboring skills of individual field laborers he closely observed in the tasks of his new system of farming. Courtesy of Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association.

Like many slaveholders in late-eighteenth century Virginia, Washington seldom wrote about or otherwise documented the violent punishment of the enslaved, but in the process of adopting the new course of husbandry and implementing the weekly reports, he explicitly discouraged the use of what he called “correction” or “severity” to extract labor from the enslaved. He instructed his several white overseers to rely instead on constant supervision as the only “sure way of getting work well done, & quietly by negroes; for when an Overlooker’s back is turned, the most of them will slight their work, or be idle altogether. In which case correction cannot retrieve either; but often produces evils which are worse than the disease.” After he suspected an overseer of repeatedly failing to spend the full day supervising the enslaved laborers at the Mansion House, Washington warned “the only way to keep them at work without Severity, or wrangling, is always to be with them.” Washington advised managers to secure the labor of the enslaved through supervision and verbal warnings, for reasons he cited as both practical and humane. In the farm manager’s supervision of the enslaved, Washington expected Anthony Whitting to prevent “all irregularities & improper conduct,” and emphasized that “this oftentimes is easier to effect by watchfulness and admonition, than by severity; & certainly must be more agreeable to every feeling mind in the practice of them.”27

Constant and vigilant supervision of enslaved laborers was Washington’s proposed alternative to whipping. Hiland Crow, in Washington’s opinion, was a capable overseer, but he was too often away visiting friends or entertaining them at his house rather than supervising the field laborers at Union Farm. The result of this inattention, Washington concluded, was “idleness, or slight work on one side, & flogging on the other.” The flogging created “dissatisfaction,” and it had on one or two occasions created what Washington described only as “serious consequences.” Washington distinguished between what he considered “just & proper” whipping and that which violated his sense of excessive force, and he expected farm managers to enforce his standard of limits on violent punishment and to regulate the overseers in the same. George Augustine Washington assured his uncle that he had not “improperly” imposed a punishment on an enslaved field laborer “by my intrusting it to the execution of an Overseer.” In fact, Jenny, suspected of intentionally destroying harvested flax, had been found not responsible for the act, but George Augustine in reporting her subsequent death of natural causes wanted to make sure Washington would never think him “capable of inhumanity.” When Washington instructed manager William Pearce to punish Abram as an example, he further stipulated that the overseer at Union Farm, where Abram worked, not be allowed to administer the punishment of the runaway. Washington did “not trust to Crow to give it to him; for I have reason to believe he is swayed more by passion than judgment in all his corrections.”28

Washington’s reference to “all” of Hiland Crow’s corrections suggests that punishment was frequent, while the assumption that violent punishment might be guided by judgment rather than passion indicates the limits of Washington’s intended protection of the enslaved. Despite his infrequent and brief visits to Mount Vernon while president, Washington was aware of the overseer’s use of the lash and was alert to evidence of unauthorized whipping. When a friend asked for a recommendation of Crow as overseer, Washington acknowledged he received “too frequent complaints of ill treatment” by Crow, although he added, “I never discovered any marks of abuse.” In his assessment, Crow’s skill as an agricultural manager outweighed his suspected cruelty. Washington told his friend that Crow would make a valuable overseer “if he is intended to be under your own eye.” Tobias Lear wrote a friend that Washington never approved of a whipping without an investigation into the alleged offense, but neither this process nor Washington’s instructions to the supervisors of labor shielded the enslaved from the regular threat of violence.29

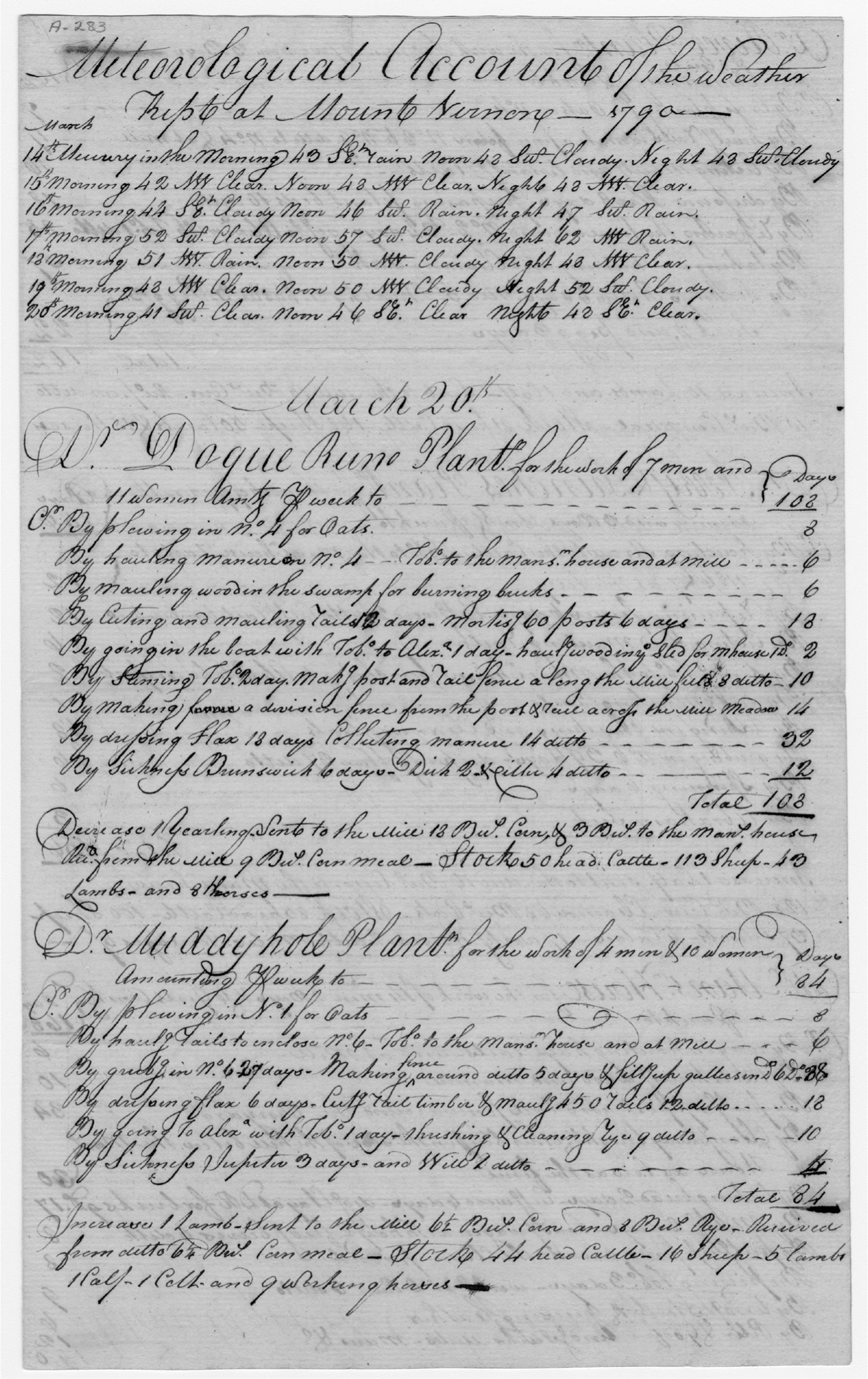

Fig 5.3 Farm Report, work done on the Mount Vernon farms, during week 14–20 March 1790. Beginning in 1785, Washington received weekly reports of the work completed by enslaved laborers at each of his plantations and in the workshops. By 1790, the reports designed by Washington were prepared in the form of double-entry bookkeeping, with each plantation debited for the number of enslaved laborers and credited for the days worked or the reasons for absence. Courtesy of Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association.

Any determination of Washington to limit physical punishment remained in conflict with his demand for more labor. By 1793 he conceded to his farm manager that if any of the enslaved refused to do their duty or were impertinent, “correction (as the only alternative) must be administered.” During his long absences from Mount Vernon during the presidency, Washington threatened to punish individuals who failed to carry out the work demanded of them. If the bricklayer Muclus did not demonstrate more industry, Washington authorized that he be both “severely punished and placed under one of the Overseers as a common hoe negro.” Isaac deserved “severe punishment” for his idleness and carelessness with the tools in the carpenter shop. The enslaved ditchers “ought to have been severely punished” for something as seemingly inconsequential as the “villainous manner” in which they repaired a fence at the mill. When Anthony Whitting wrote that he had given the enslaved seamstress Charlotte a good whipping for what he characterized as “impudence” and that he was “determined to lower her Spirit or Skin her Back,” Washington replied that the treatment of Charlotte was “very proper.”30

Washington required farm managers to enforce whipping or other punishments for various kinds of behavior unrelated to the performance of work, such as running away, stealing, or fighting. He expected Whitting to punish both individuals involved in any fight, unless the manager could be certain that only one person was at fault. After a slave he identified as Matilda’s Ben continued to misbehave following punishment for assaulting another slave, Washington explained to Whitting that if the young man “should be guilty of any attrocious crime, that would affect his life he might be given up to the Civil authority for tryal; but for such offences as most of his colour are guilty of, you had better try further correction; accompanied with admonition and advice. The two latter sometimes succeed when the first has failed.” This instruction to Whitting is among the few surviving documents in which Washington characterized behavior by race as well as condition of servitude. He reaffirmed his preference for the verbal warnings that might avert violent punishment, but he also made clear that he would enforce his own system of discipline and control separate from any court of law. He stipulated punishments for infractions small and large. When William Pearce reported that someone broke into the smokehouse and stole several pieces of bacon, Washington ordered him to find the thief “& bring him to punishment.” After an enslaved man from a neighbor’s property visited River Farm and brutally beat his wife who lived there, Washington sent orders to Pearce that if the man ever came back “you are to give him a good whipping, & forbid his ever returning.” After complaining about the loss of sheep and hogs and imposing strict restrictions on the number of dogs at each plantation, Washington declared to Whitting that “if any negro presumes under any pretence whatsoever, to preserve, or bring one into the family, that he shall be severely punished, and the dog hanged.” Washington’s expectation that an example be made of Richmond for stealing money from a hired servant or Abram for running away suggests that whippings were conducted in front of other members of the enslaved community. The enslaved individuals who voiced complaints to Washington about Hiland Crow must have expected him to enforce limits on violence, but Washington’s frequent threats of severity, often expressed in anger and frustration, exposed the tenuous and conditional protections against punishment.31

From Washington’s perspective, the most serious betrayal of the presumed duty of an enslaved laborer was the act of running away. During the years in which he established a new system of slave management and up until the end of his life, even as he developed a more critical perspective on slavery and considered emancipation, Washington defended the private property rights of slaveholders. When the enslaved servant owned by an Alexandria merchant visiting Philadelphia approached a Quaker group to help him win his freedom in court, Washington was so incensed that he wrote Robert Morris to express his concern. He assured Morris that he did not want to hold slaves in bondage, but considered the Quakers’ efforts to “seduce” enslaved persons into freedom an assault on property rights that would deter anyone with enslaved servants from doing business in Philadelphia, then the nation’s commercial center. Washington was particularly concerned that the Quakers had “tampered” with slaves who are “happy & content to remain with their present masters.” Several months later, Washington engaged in a complicated deception to return a runaway enslaved valet owned by William Drayton, who had stayed at Mount Vernon on his journey from a meeting of the Confederation Congress to his home in South Carolina. When Jack, the enslaved valet, ran away and returned to Mount Vernon, Washington devised a plan by which he sent Jack on an errand to Baltimore, where an associate of Washington had arranged his recapture and passage to Charleston.32

By the time of his presidency, Washington defended his right to recover slave property at the same time that he sought to shield his reputation, particularly in those sections of the country where popular sentiment might oppose the recapture of escaped slaves. When Paul, one of the enslaved field laborers hired from Penelope French, ran away in 1795, Washington offered to share with the French family the costs of recapture, but he asked that his name not appear in a printed advertisement or in any other way be associated with the effort. After the farm manager, William Pearce, placed an advertisement in an Alexandria newspaper that offered a reward for the capture of Paul, who was described as a runaway from one of the president’s farms, Washington explained that he “had no other objection to the advertising of Paul than that of having my name appear therein; at least in any papers North of Virginia.” When Ona Judge, the enslaved servant of Martha Washington, escaped in 1796, Washington’s steward placed an advertisement in the Philadelphia newspaper that identified Judge as absconding “from the household of the President of the United States.” In his determined efforts to recapture Judge and the enslaved chef, Hercules, who ran away from Mount Vernon in February 1797, Washington relied primarily on private correspondents and the work of hired agents.33

Just as running away continued to be the most serious perceived challenge to the authority of Washington and his overseers, so Washington considered sale and separation from family to be the most serious punishment he inflicted on any enslaved person. As he had before the Revolutionary War, Washington sold a man to the Caribbean in 1791 as a punishment. The offense of the man he designated as Waggoner Jack went unspecified in the account book that recorded his transportation to the islands and the return in wine and commission on the sale. Washington instructed the farm manager to warn Ben and his parents “in explicit language that if a stop is not put to his rogueries, & other villainies by fair means & shortly; that I will ship him off (as I did Waggoner Jack) for the West Indias, where he will have no opportunity of playing such pranks as he is at present engaged in.” While most runaways were punished and sent back to work after their recapture, Washington in 1795 approved the sale of a young man named Anderson who had run away from John Dandridge, who managed more than thirty slaves owned by Washington in New Kent County.34

From the time Washington recognized that he would be leaving to serve as president, he and his manager steadily replaced the five enslaved overseers serving as late as the fall of 1788, and by early 1793, only Davy Gray, by then at Muddy Hole, remained among them. Morris, who had been overseer at Dogue Run Plantation since 1766 became sick in 1790 and was initially replaced by Will, the former overseer at Muddy Hole. Will remained as overseer of Dogue Run until he was replaced by a hired man in late 1791. Another enslaved overseer named Will, at French’s Plantation, was replaced by James Bloxham in late 1788. In March 1789, as Washington prepared to leave for his inauguration, he placed Isaac, the overseer of enslaved carpenters, under the supervision of Thomas Green, a hired joiner in whom Washington had little confidence.35

Anticipating that he would be away from Mount Vernon for months at a time over at least the next four years, Washington decided to rely on white overseers to enforce a rigorous schedule of year-round work, even though he had little faith in most of the hired overseers. William Garner at River Plantation was a “rascal,” who “never turned out of mornings until the Sun had warmed the Earth; and if he did not, the Negros would not.” Washington accused Henry Jones at Dogue Run of allowing the field laborers to remain idle “to bribe them against a discovery of his own idleness.” Although Hiland Crow at Union Farm was a skilled farmer, he was too often away from home, “the consequence of w[hi]ch (supposing the negros had been idle during his absence) was, that he and his charge were perpetually at varience.”36

In a detailed evaluation of the overseers prepared for the arrival of manager William Pearce, Washington in December 1793 reported “Davy at Muddy hole carries on his business as well as the white Overseers, and with more quietness than any of them. With proper directions he will do very well, & probably give you less trouble than any of them, except in attending to his care of the stock, of which I fear he is negligent.” Washington’s opinion of Davy Gray stood in sharp contrast to his view of the white overseers. Henry McCoy at Dogue Run appeared to Washington “a sickly, slothful and stupid fellow.” James Butler at the Mansion House had no authority over the enslaved laborers, and Crow at Union Farm, though knowledgeable, was negligent in the supervision of the enslaved as well as the horses. Washington warned Pearce, “Thomas Green (Overlooker of the Carpenters) will, I am persuaded, require your closest attention, without which I believe it will be impossible to get any work done by my Negro Carpenters.” Only William Stuart at River Farm escaped Washington’s harsh assessment. Stuart was industrious and worked long days, and he also seemed “to live in peace & harmony with the Negroes who are confided to his care. He speaks extremely well of them, and I have never heard any complaint of him.” The only fault Washington could find in Stuart was that he talked too much and “has a high opinion of his own skill & management.”37

On his intermittent visits to Mount Vernon while president, Washington spoke directly with enslaved laborers, interposing himself between them and the manager or overseers and gathering information on his own terms. On several visits he received multiple complaints from the enslaved. He learned that the reduction in the amount of cornmeal distributed to the quarters left families hungry. On his ride to the plantations, Washington looked for signs of physical abuse, and he listened to complaints about mistreatment by white overseers. The enslaved workers at the plantations evidently considered Washington receptive to their appeals. When in 1790 George Augustine proposed to move Davy Gray from oversight of Muddy Hole Plantation to be overseer of the larger farm at Dogue Run, Gray protested that his earlier bout of jaundice left him too weak to take on the greater responsibility, and he was confident that Washington would agree not to relocate him. George Augustine informed Washington of Gray’s appeal, and though no response survives, Gray continued to supervise Muddy Hole until the end of Washington’s life. Washington trusted Gray enough to consult with him about complaints from other slaves.38

The success of Gray as an overseer never persuaded Washington to employ another enslaved overseer in place of the hired men, who, with the exception of Stuart, turned over with disruptive frequency. George Augustine Washington in 1790 proposed to avoid “the expence and frequently the perplexity of white Overseers” by installing James, an enslaved carpenter, as overseer of one of the plantations, and he believed James “might answer as well as an Overseer as any white man.” Washington rejected the proposal, as he would refuse a later suggestion that he place Will, formerly the enslaved overseer at Muddy Hole and Dogue Run, as overseer at the Mansion House. Washington was willing to entrust Will with special responsibilities, including tasks not subject to immediate supervision, but he was concerned that Will “feels hurt in being superceded in his Overseership.”39

In his written hiring agreements with the overseers and in his instructions to the managers who supervised them, Washington demanded that the overseers be present and with the slaves under their supervision throughout the workday. Washington ordered an overseer to “see the labourers at their work as soon as it is light in the morning” and each overseer should “be constantly with some part or other of his People at their work.” “With me, it is an established maxim, that an Overseer shall never be absent from his people but at night, and at his meals.” Even when the enslaved were not working, Washington expected the overseers to exercise a certain supervisory authority. He discouraged their entertainment of friends, other than family “now and then,” and he expected the overseers to remain on the plantation except on Sundays, when, as he specified for one, “he may occasionally go to Church.” The burden of enforcing these agreements, particularly during Washington’s absences, fell on the farm managers, who Washington expected to hire overseers of “good character” and reputation, “& knowing in the management of Negros.”40

Anthony Whitting arrived at Mount Vernon in 1790 with experience managing enslaved agricultural labor on a similar estate of even larger acreage on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. The Shrewsbury Farm had been owned by General John Cadwalader, Washington’s fellow officer in the Continental Army, and since Cadwalader’s death in 1786, Whitting had been the manager of farming at the estate. There he supervised nearly 50 adult slaves and more than 30 enslaved children in the same kind of improved farming found on Washington’s estate. The field laborers at Shrewsbury worked with a large inventory of plows, harrows, and scythes, and cared for the varied livestock. When Whitting presented himself as a candidate for overseer at Mount Vernon, George Augustine Washington found his manner of conversation “much superior to what is met with among people of that pursuit,” and Whitting quickly moved from overseer of one plantation to manager of all farming at the estate. As overseer, Whitting was required by the articles of agreement drafted by Washington to “be particularly attentive to the Negroes which shall be committed to his care,” and as manager he was advised by Washington that the example he set, “be it good or bad, will be followed by all those who look up to you. Keep every one in their places, & to their duty.” Washington reminded Whitting of something at the core of his own approach to the management of labor, enslaved or hired. “One fault overlooked begets another—that a third—and so on—whereas a check in the first instance might prevent a repetition, or at any rate cause circumspection.”41

A member of the Cadwalader family had cautioned Washington that Whitting, though knowledgeable about agriculture and the economy of a farm, was too indulgent of his pleasures. During Whitting’s three-year tenure, he gained Washington’s considerable confidence, in large part because of his knowledge of the practice of husbandry in his native England, but following the death of Whitting in June 1793, Washington received reports of the manager’s drinking and his association with “bad company” at Washington’s house in Alexandria. He had been, Washington concluded, “a very debauched person,” unable to govern the overseers or to manage the details of the estate’s business. Whitting, following James Bloxham, became for Washington one more example of a knowledgeable English farmer unprepared to supervise enslaved Blacks. Washington warned a subsequent manager of the inherent risks of hiring English farmers or European tradesmen unfamiliar with slavery: “Rather than persevere in doing things right themselves, & being at the trouble of making others do the like, they will fall into the slovenly mode of executing work which is practiced by those, among whom they are.”42

After the death of Whitting, Washington searched for a new farm manager who would bring both knowledge of mixed agriculture and experience in the supervision of enslaved laborers. He believed that he was most likely to find that ideal manager on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, where Whitting had previously worked and where there was the greatest concentration of large estates operating under the same farming system as Mount Vernon. It was also on the Eastern Shore where Washington was confident that he would find someone who met his second requirement: “a residence of some years in a part of the Country where the labour is done by Negroes.” It was that experience with the management of enslaved labor that Washington deemed essential to the direction of the several large farms under separate overseers. Washington made inquiries that brought him the names of managers on some of the largest and most successful estates on the Eastern Shore, and he then consulted with his friend, Eastern-Shore resident William Tilghman, to ensure that no measures taken on his behalf would have the appearance of enticing a manager away from an estate owner to whom he was engaged.43

Among those whom Washington consulted in Maryland was Jacob Hollingsworth, an innkeeper in Elkton. Washington occasionally stayed at the inn while traveling between Virginia and Philadelphia, as did Thomas Jefferson, who had hired a farm manager recommended by Hollingsworth. As Jefferson prepared to introduce at Monticello the crop rotations he had discussed with Washington and others in Philadelphia, he searched for a farmer from the area around Elkton because, as he explained to Hollingsworth, “the degree of farming there practised is exactly that which I think would be adopted in my possessions, and because the labour with you being chiefly by Negroes, your people of course understand the method of managing that kind of laborer.” Jefferson informed his son-in-law and manager “the farmers there understand the management of negroes on a rational and humane plan.” Hollingsworth assured Jefferson that the manager he identified for work at Monticello was “as neat a Farmer as Any in our Ne[i]ghbourhood,” and able to manage Negroes “tho not in a very harsh manar.” Jefferson, apparently alluding to an earlier conversation, told Washington he had “engaged a good farmer from the head of Elk (the style of farming there you know well),” and expressed his hope the farmer would assist him in the adoption of Arthur Young’s model of husbandry.44

Washington did not hire the manager suggested by Hollingsworth, selecting instead William Pearce, a long-time manager of a Ringgold family estate in Kent County, Maryland. Pearce would prove to be the most satisfactory farm manager with whom Washington ever worked, and from the beginning of their relationship, Washington demonstrated a surprising trust in Pearce. In their written agreement and in early conferences, Washington emphasized the necessity of reestablishing the accountability of the overseers and all superintendents of laborers, “for it may be received as a maxim that if they are away or entertaining company at home, that the concerns entrusted to them will be neglected, & certainly go wrong.” To that end, Washington delegated unprecedented control over overseers, all of whom Pearce was authorized to hire or discharge, according to his own judgment.45

By the time Washington hired William Pearce, experience in the management of enslaved laborers had become a priority in any hire involving supervisory duties at Mount Vernon. The disappointment with Bloxham and Whitting was reinforced by other hires of artisans and overseers inexperienced in the management of enslaved labor. As early as 1787, Washington had dismissed a suggestion to hire the newly arrived brother of Cornelius Roe, a bricklayer at Mount Vernon, because, as Washington wrote George Augustine, “I can hardly believe that a raw Irishman can be well qualified to manage Negros.” When Washington met the Irish immigrant James Butler in Philadelphia in 1792, he was so impressed with his knowledge of farming and livestock that he hired him to manage the Home House farm, but from their first meeting, Washington was apprehensive that Butler “will be at a loss in the management of Negros—as their idleness & deceit, if he is not Sufficiently cautioned against them, will most assuredly impose upon him.” When he first saw him at work at Mount Vernon, Washington thought Butler lacked the requisite “activity & Spirit.” By the end of the year he was persuaded Butler “has no more authority over the Negroes he is placed, than an old woman would have; and is as unable to get a proper days Work done by them as she would.” After Butler was dismissed as an overseer, Washington provided him with a certificate attesting to his honesty and hard work, further explaining “I part with him for no other cause than for his not being accustomed to the management of negros prone to, & who had been long in the habits of idleness.”46

The perceived inadequacies of Butler included his appearance and demeanor, both of which Washington considered essential components in the exercise of authority over enslaved laborers. His initial reason for doubting the ability of Butler to manage slaves was “his clumsy appearance, and age.” Washington had also questioned the wisdom of hiring Roe’s brother because “his appearance may be very much against him.” Washington doubted the Scottish carpenter he hired in Philadelphia would have any authority over the enslaved carpenters at Mount Vernon, “as he appears to be a simple, inoffensive man.” When Washington was approached by a man who hoped to replace Butler as overseer, he explained to William Pearce the need to balance the applicant’s bearing against his experience: “He is a tolerably good looking man and has the appearance of an active one—but how far any man, unacquainted with Negros, is capable of managing of them, is questionable.”47

Despite his largely successful efforts to train enslaved laborers in the varied skills he required for his increasingly complex farming operations, Washington continued to hire some artisans with valuable skills, even if those individuals did not have experience in the supervision and direction of enslaved laborers. British experience continued to hold sway with Washington. James Donaldson, the Scottish carpenter whom Washington met and hired in Philadelphia in 1794, brought to Mount Vernon essential skills as a wheelwright and manufacturer of plows. Washington anticipated that Donaldson would be valuable for making equipment for the farms and repairing spinning wheels, as well as for training enslaved artisans in the same skills, and the agreement presented by Washington required Donaldson to instruct any of the enslaved carpenters who were committed to his care and management. Washington expected Donaldson to “take pains to teach those who work with him,” especially the experienced carpenter, Isaac, and a boy named Jem, that they would learn more about making essential agricultural implements, including plows, harrows, and carts. Two months after the arrival of Donaldson, however, the farm manager confirmed Washington’s suspicions that the man might be inadequate to the job of managing the enslaved carpenters. Although a good and industrious workman, Donaldson “has not spirit and activity enough to make the hands entrusted to his charge, do their duty properly.” Washington so doubted Donaldson’s ability to manage the enslaved artisans that he was willing to hire an additional, if less talented, carpenter “more competent to the Management of the Negros,” to work alongside him.48

Donaldson was one in a succession of hired artisans Washington expected to instruct slaves who then might be able to assume the greater variety of tasks that supported the agricultural improvements adopted after 1785. The ditcher James Lawson was required by articles of agreement to train any slaves put under his direction, and to keep them closely at their work “without relaxing (under the idea of being an overseer) or neglecting, in any shape whatever, his own labour.” John and Rachel Knowles, hired as a bricklayer and spinner, respectively, agreed “to take under their directions and carefully instruct such Negroes as the said George Washington may think proper in the different duties required of them.” Once Thomas Green assumed supervisory duties as joiner and carpenter, Washington expected him to instruct in his trade any enslaved carpenters placed under his direction.49

As Washington recognized, the hire of artisans unfamiliar with slavery or of overseers with insufficient authority threatened to disrupt the racial and social order at his estate. In the weeks following Donaldson’s arrival at Mount Vernon, Washington was anxious that the carpenter and his family might “get disgusted by living among the Negros,” but he was equally concerned that Donaldson might become too friendly with the enslaved carpenters or other laborers. He instructed William Pearce that Donaldson should be “kept as seperate, and as distinct as possible from the Negros—who want no encouragement to mix with, & become too familiar (for no good purposes) with these kind of people.” A month later, Washington again asked Pearce to caution Donaldson “against familiarities with the Negros.” Washington was especially concerned that the overseers at the plantations would associate too closely with the slaves under their supervision. When John Allison became the overseer at the Mansion House in 1794, Washington feared “that he would be too familiar with those he overlooked, and of course would carry no authority.” The renegotiated articles of agreement with Thomas Green as overseer of carpenters in 1790 required “that neither he nor his family will have any connection or association with any of the Negroes except those immediately under his direction and with those but where it relates to their business.” The agreement apparently had little effect, since among the many criticisms Washington later directed against the carpenter was that “he is too much upon a level with the Negroes.”50

Washington believed the authority of the farm managers depended on some kind of social distance from the white overseers as well as the enslaved. He cautioned William Pearce that “to treat them civilly is no more than what all men are entitled to, but my advice to you is, to keep them at a proper distance; for they will grow upon familiarity, in proportion as you will sink in authority, if you do not.” The reserve and detachment that Washington expected from every supervisor of labor introduced the potential for suspicion and mistrust in nearly every personal interaction among overseers, hired laborers, and the enslaved. Washington assumed the need for a social order that divided whites between those who might dine at his table and those who did not enter the Mansion House, and he expected all of the whites to maintain a greater separation from Blacks, even as they spent their days together in close work. No surviving record reveals Washington’s acknowledgment of what he knew well, that hired white men fathered children with enslaved women.51

On varied occasions, often in the field where the practical evidence surrounded him, Washington recognized the agricultural skill and knowledge of the enslaved. When peas failed to come up as usual at Muddy Hole plantation in 1786, Washington noted “this my Negros ascribed to planting them too early, whilst the earth was too cold—& not sufficiently dryed.” When he briefly reintroduced tobacco cultivation in 1789, Washington consulted with the enslaved overseer at French’s plantation, as “Frenchs Will understands the managemnt of it better than I do.” Washington included the enslaved overseers in the direction of his agricultural experiments, and conferred with the plow drivers, although he disagreed with their assessment, about the performance of a new plow sent from Arthur Young.52

His most detailed recognition of the agricultural skills of laborers appeared in an annotated list of the slaves Washington hired from Penelope French. Intent on reducing the number of slaves under his management during his retirement, Washington in the summer of 1799 proposed to return these hired slaves to French. He suggested the two parties select disinterested persons who would produce a valuation of the slaves, “after comparing the old with the young—and the chances of increase and decrease,” and then determine an annuity to be paid to Washington during the remaining term of the agreement. Washington had an incentive to present the hired slaves in a favorable light, but the specificity of his comments and his knowledge of their work reflected a lifetime of monitoring and assessing individual laborers on his estate. What is perhaps most striking about Washington’s summary is how many of the individuals he described excelled at their work. Pascal was a “very good Mower, both of Grain & Grass, and an excellent Ditcher.” Tom, also good at mowing, was “an excellent Ploughman,” despite the serious impairment that would eventually leave him blind. Julius, though physically impaired since infancy, was “a very good Carter, and can do any other work.” Isaac’s skills spanned the seasons of work: “an excellent Scythesman, a good Ploughman, and handy at any other business on a Farm.” Sabine, at sixty, was “a good working woman, notwithstanding her age.” Daphne “Ploughs very well,” and Washington said the same of Grace and Siss. Other women carried out only “common work,” and Washington described them largely by their appearance. Milly was “a full grown woman, and likely,” and Hannah “nearly at her full growth and a woman in appear[anc]e.” Will, once an overseer and later a foreman, was now “old, but hearty” and tended the stock and repaired fences. Only Lucy prompted Washington’s suspicions. At about fifty-five years old, she was “Lame, or pretends to be so,” but Washington admitted she was “a good knitter, & so employed.”53