“SURPRISE ATTACK…”

“OUT OF THE BLUE…”

“NO ONE COULD HAVE SEEN IT COMING…”

When people talk about Pearl Harbor, these phrases are often part of the story. But the truth is, while no one knew the exact date and time Japan would strike Hawaii, the attack wasn’t a total surprise. Or at least it shouldn’t have been. There were all kinds of warning signs. It didn’t really come “out of the blue,” and someone did see it coming, seventeen years before it happened.

In 1924, US Army officer William “Billy” Mitchell predicted the attack. Mitchell had coordinated a huge air campaign for the US Army during World War I. After that war, he argued that America needed a separate air force. (Back then, the army and navy had planes, but the US Air Force wouldn’t exist as a separate branch of the military until 1947.)

Mitchell had been sent on a tour of the Pacific and Far East to evaluate the preparedness of US forces. When he got home, he warned that Japan’s ideas about expanding its empire would eventually lead to war with the United States, starting with a surprise attack. And check out the details he included in his report….

![ATTACK WILL BE LAUNCHED AS FOLLOWS: BOMBARDMENT ATTACK TO BE MADE ON FORD’S [SIC] ISLAND [IN PEARL HARBOR] AT 7:30 A.M…. ATTACK TO BE MADE ON CLARK FIELD [PHILIPPINES] AT 10:40 A.M.](../images/9780593120392_Page_018_Image_0001.jpg)

Mitchell nailed it, right down to the hour of the Pearl Harbor attack. The first bombs would be dropped just before 8:00 a.m. And Japan would, in fact, attack Clark Field in the Philippines a few hours later. But at the time of Mitchell’s warning, nobody paid much attention. Perhaps that was because Mitchell had a reputation for being loud and opinionated. He had little patience for anyone who didn’t agree with him, and he often criticized his bosses. Or maybe it was because people were busy and there was just too much to keep track of. Whatever the reason, they tossed Mitchell’s report in a file and forgot about it.

Mitchell wasn’t the only one who thought Pearl Harbor might be a target. In 1938, a US War Department survey said the same thing and added that if the Japanese did attack, there would be no warning. By early 1941, Japanese military leaders had their sights set on Pearl Harbor, too.

1941: WHO WAS IN CHARGE?

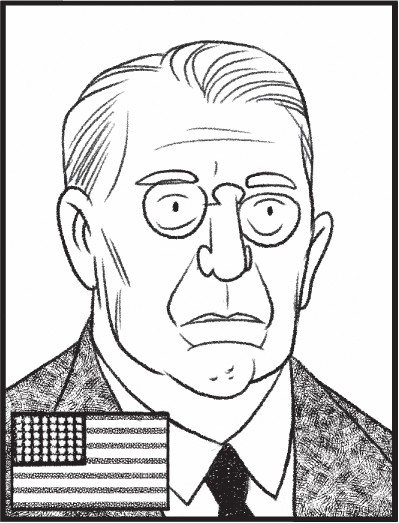

THE PRESIDENT: Franklin Delano Roosevelt had just been reelected president of the United States. He knew that most of the American people didn’t want war, so he kept talking with Japanese leaders, trying to come up with an agreement to keep the peace. But at the same time, Roosevelt believed that war might be inevitable.

THE EMPEROR: Hirohito was Japan’s longest-ruling monarch. He served as emperor from 1926 to 1989. Officially, he was the country’s leader in 1941, but historians believe that Japan’s military leaders were holding most of the real power at that time.

THE PRIME MINISTER: Konoe Fumimaro was Japan’s prime minister. He was trying to keep the military’s power in check and hoped to avoid war with the United States. He spent months negotiating with America, but in October he was forced to resign over differences with Japan’s army minister.

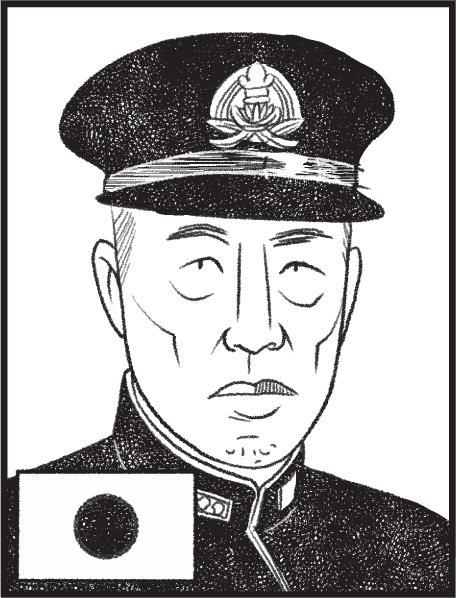

ARCHITECT OF THE ATTACK: Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto was in charge of the Japanese fleet and planned the attack on Pearl Harbor. Yamamoto had studied in America, at Harvard. He didn’t want war with the United States, but he was convinced that if it happened, Japan’s only chance would be to strike first. He’d called the US Pacific Fleet in Hawaii “a dagger being pointed at our throat.” In January 1941, he wrote to Japan’s Navy Ministry, “The most important thing we have to do first…is to fiercely attack and destroy the US main fleet at the outset of the war, so that the morale of the US Navy and the American people goes down to such an extent that it cannot be recovered.”

THE AVIATOR: Commander Minoru Genda was a well-respected pilot who helped Yamamoto plan the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Genda suggested that Japan strike Pearl Harbor in three waves, with bomber and fighter planes launched from aircraft carriers. Genda knew the attack had to be a surprise, so he urged Yamamoto to keep the plans top secret.

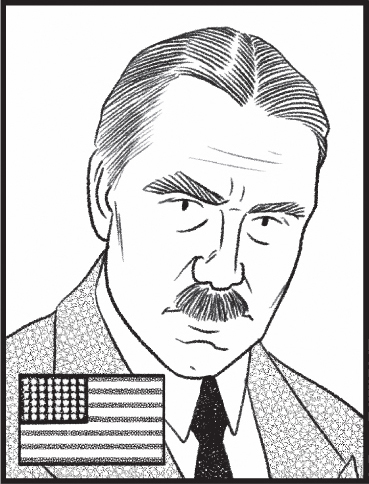

THE NAVY MAN: Frank Knox had been appointed US secretary of the navy in 1940. In January 1941, he wrote a letter to Secretary of War Henry Stimson, saying he believed a Japanese attack was possible. Knox promised the military would take another look at whether Pearl Harbor was prepared.

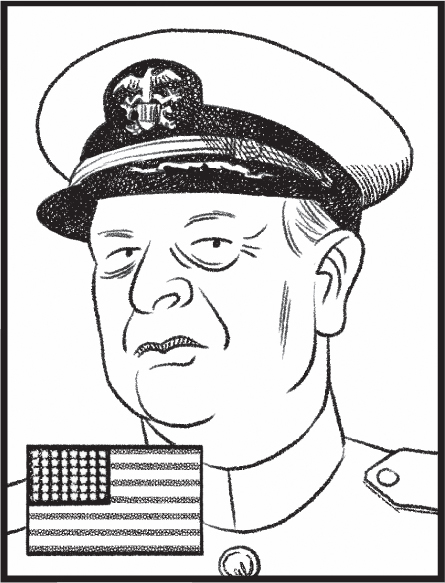

THE FLEET COMMANDER: In February 1941, Admiral Husband E. Kimmel was appointed commander of the Pacific Fleet stationed at Pearl Harbor. Right away, he requested better defenses there. It was his job to train the fleet so it would be prepared for war.

THE ARMY COMMANDER: Lieutenant General Walter C. Short took command of the US Army’s Hawaiian Department in February 1941. His main jobs at Pearl Harbor were to keep the fleet safe and to maintain the coastal defense of Oahu. Those jobs weren’t easy; his equipment was old, and he didn’t have enough men.

THE AMBASSADOR: Despite all the secrecy surrounding plans to attack Pearl Harbor, Joseph Grew, America’s ambassador to Japan, caught wind of the plot within a month. He sent a cable (a message transmitted via undersea cables) to Washington:

There it was—a warning of what was about to happen, clear as day. So why wasn’t America ready? The truth is, no one took Grew’s warning very seriously. Military officials had decided that Japan was probably going to attack the Philippines instead.

By February 1941, Yamamoto was fine-tuning his idea to attack Pearl Harbor. The plan was to destroy the American battleships and aircraft carriers stationed there. Yamamoto figured that would give Japan six months to conquer more of Asia before the United States could rebuild its fleet.

LIKE SOMETHING OUT OF A NOVEL

A 1925 novel called The Great Pacific War by Hector C. Bywater included a Japanese attack on American naval forces in the Pacific. Could Yamamoto have gotten the idea for his attack on Pearl Harbor from this book? No one knows for sure, but the book was translated into Japanese, and there are some reports that Yamamoto had read it. Either way, an attack on Pearl Harbor made sense to Japanese military leaders at the time. Japan wanted to build its empire so it could have more natural resources like iron, oil, rubber, and tin. It wanted to expand farther, into Malaya, the Philippines, and the Dutch East Indies, and hoped that an early attack on Pearl Harbor would keep America from getting in the way.

American military leaders had obviously thought about the possibility of an attack. In March, commanders of the army and navy air fleets in Hawaii wrote a memo outlining a plan to defend Oahu. It suggested that the military start regular air patrols around the island, going as far out to sea as possible so they’d be more likely to spot signs of a coming attack. That was a great idea, but with a shortage of both people and planes, it was easier said than done.

Meanwhile, back in Japan, Commander Minoru Genda was put in charge of preparing the men who would carry out the attack. His pilots trained through the summer at Kagoshima Bay in southern Japan, which had a layout similar to Pearl Harbor. That was important when it came to torpedoes, the underwater missiles that explode when they hit a target. Most torpedoes had to be dropped into water that was at least sixty to seventy feet deep or they’d hit bottom before they reached their target. But Pearl Harbor was only thirty to thirty-five feet deep, so the Japanese had to redesign their torpedoes. They came up with a new version, known as the Thunder Fish, that worked in shallower water.

This torpedo was discovered during a dredging operation in Pearl Harbor in 1991. The torpedo was nearly intact when it came up from the sea in the bucket of a crane. Its warhead was still armed, so navy explosives experts took it out to sea and detonated it. After the blast, they were able to recover this section of the rear part of the torpedo, which is now on display at the Pearl Harbor Visitor Center.

You might think that with all this training going on in Japan, America would at least hear rumors about what was happening. But Yamamoto and the other military leaders were careful to keep the plan a secret. They were so careful that Japan’s ambassador to the United States, Kichisaburo Nomura, claimed that even he didn’t know about it.

The United States had intelligence officers and code breakers working to figure out what Japan might be planning. In the summer of 1940, they’d cracked the code that was used to send messages to Japanese diplomats. That was thanks to a new code-breaking tool called “Purple.” It was a special machine that helped code breakers decrypt information. They called that decoded intelligence “Magic.” But they hadn’t managed to crack the code that Japan’s military used, so they weren’t getting all the information that was being relayed. By late 1941, American intelligence officials had intercepted enough messages to know that war was imminent. They understood that Japan was planning some kind of attack. They just didn’t know precisely when or where it was going to happen.

Intelligence gathering was tricky business. Sometimes there simply weren’t any messages to decode. Many messages that were decoded also had to be translated. And sometimes, when code breakers did manage to learn important information, it wasn’t communicated to the right people.

In September 1941, American intelligence officers found out that Japan’s navy was looking for information about where Pearl Harbor’s battleships were located. You’d think that would be a huge warning sign, but it was mostly ignored. Nobody even told Admiral Kimmel that Japan was asking where he kept his ships.

In the fall of 1941, Japan sent special envoy Saburo Kurusu to Washington, DC, to help Nomura in talks with US officials. Japan was in a tough spot. The iron and oil embargo that the United States had started after the Japanese invasion of French Indochina prevented Japan from getting the natural resources it needed. Emperor Hirohito was hoping for an agreement to keep the peace, but by then Japan had a new prime minister, the more warlike Hideki Tojo. He didn’t think Japan should give in to any of the US demands.

Still, Japan’s ambassador presented a proposal: if the United States would start trading with Japan again, the Japanese agreed not to make any new advances into East Asia. The two sides kept meeting and talking that fall. But at the same time, Japan was getting ready to attack. Negotiations were still happening when the Japanese fleet set out for Hawaii in late November. Six aircraft carriers braved enormous waves in the middle of the night, keeping radio silence so they wouldn’t be detected.

On November 27, 1941, US Secretary of State Cordell Hull rejected Japan’s offer. A promise of no more invasions wasn’t enough. The United States demanded that Japan pull out of China completely…or else. Japan considered that a declaration of war.

“IF JAPAN AND THE UNITED STATES REACHED SOME KIND OF AGREEMENT AND SUCCEEDED IN THE PEACE NEGOTIATIONS, WE WOULD RETURN TO JAPAN. BUT I HAD NO IDEA ABOUT THAT. I COULD ONLY PRAY TO GOD.”

—JAPANESE TORPEDO PLANE PLOT LT. HIRATA MATSUMURA

Two days later, Hull got his hands on a copy of a speech that Tojo had given to inspire Japan’s military. It sounded like the sort of speech someone would give when they were getting ready to go to war. Hull called Roosevelt, who was on a short vacation in Georgia. Hull told the president a Japanese attack seemed imminent and suggested that he come home. So Roosevelt packed his bags and headed back to Washington the next morning.

On December 1, Emperor Hirohito met with Prime Minister Tojo and gave the go-ahead for war. Chuichi Nagumo, the Japanese admiral who would oversee the attack on Pearl Harbor, was on his way there when he got a message from Yamamoto.

You might be thinking, “Hey, wait! The strike on Pearl Harbor happened on December 7, didn’t it?” You’re right about that. But Japan is on the other side of the international date line, so the morning of December 7 in Hawaii was actually December 8 in Japan.

As the Japanese fleet made its way to Pearl Harbor, the United States had some chances to learn what was happening. On November 27, Kimmel and Short had received a “war warning” from DC, letting them know that Japan might be preparing to hit an American military target in the Pacific. So on December 2, Kimmel asked for an update on Japan’s aircraft carriers. He was told that some of them were missing. Just…missing. Maybe they were somewhere in Japan’s home waters, but nobody was sure.

You might think that would be a major red flag and that it would prompt Kimmel to increase those patrols around Oahu. But that’s not what happened. At the time, both Kimmel and Short were more worried that Japanese Americans who lived in Oahu might sabotage America’s military.

In December 1941, more than a third of the people in Hawaii were of Japanese descent. Many were American citizens who’d lived on Oahu their whole lives. There had been absolutely no intelligence to suggest they were planning anything to harm their country. But military leaders still thought that was a major concern. Their fear was based on prejudice—not actual information—and it distracted them from the real threat. It even led them to line up the planes at Hickam Field, an army air base on Oahu, so they’d be safer from sabotage—a decision that we now know made the planes a better target for the air attack that was coming.

On December 3, American intelligence officers intercepted and decoded even more Japanese messages. One asked for additional reports about the location of the warships at Pearl Harbor. There was also a conversation between the Japanese ambassadors to the United States and Prime Minister Tojo. The ambassadors were wondering if it might still be possible to avoid war if they met with the Americans once more. Tojo replied that it would be inappropriate for them to suggest another meeting at that point.

Meanwhile, those “missing” Japanese aircraft carriers were getting closer and closer to Pearl Harbor.