Chapter Two

And we be brethren

The 7th (Service) Battalion (Accrington) East Lancashire Regiment was part of Lord Kitchener’s Fourth New Army, (K4). Four companies, each with four platoons, made up the Battalion.1 ‘A’ Company, composed mainly of Accrington men and ‘B’ Company, men from the ‘Districts’ i.e. Clayton-le-Moors, Church, Oswaldtwistle, Rishton and Great Harwood were to train in Accrington; ‘C’ Company in Chorley and ‘D’ Company in Burnley. The fifty men of the Blackburn Detachment of ‘C’ Company were to train in Accrington. Kitchener’s directive of September 4th ensured the T. A. drill halls in Accrington, Burnley and Chorley were available, with officers such as Captain Robinson and Lt. Cockshutt of Burnley T.A., together with some senior N.C.O.’s to temporarily assist with training.

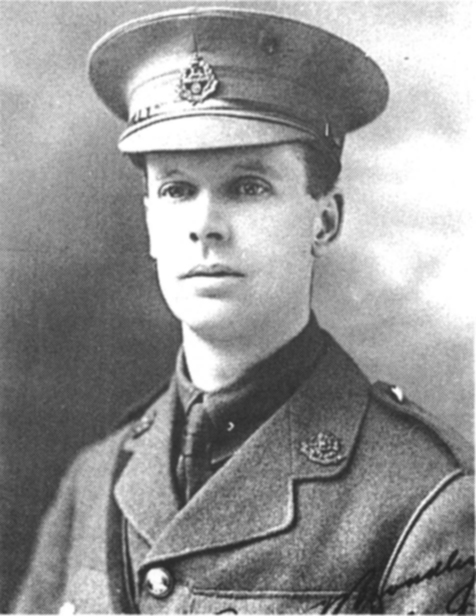

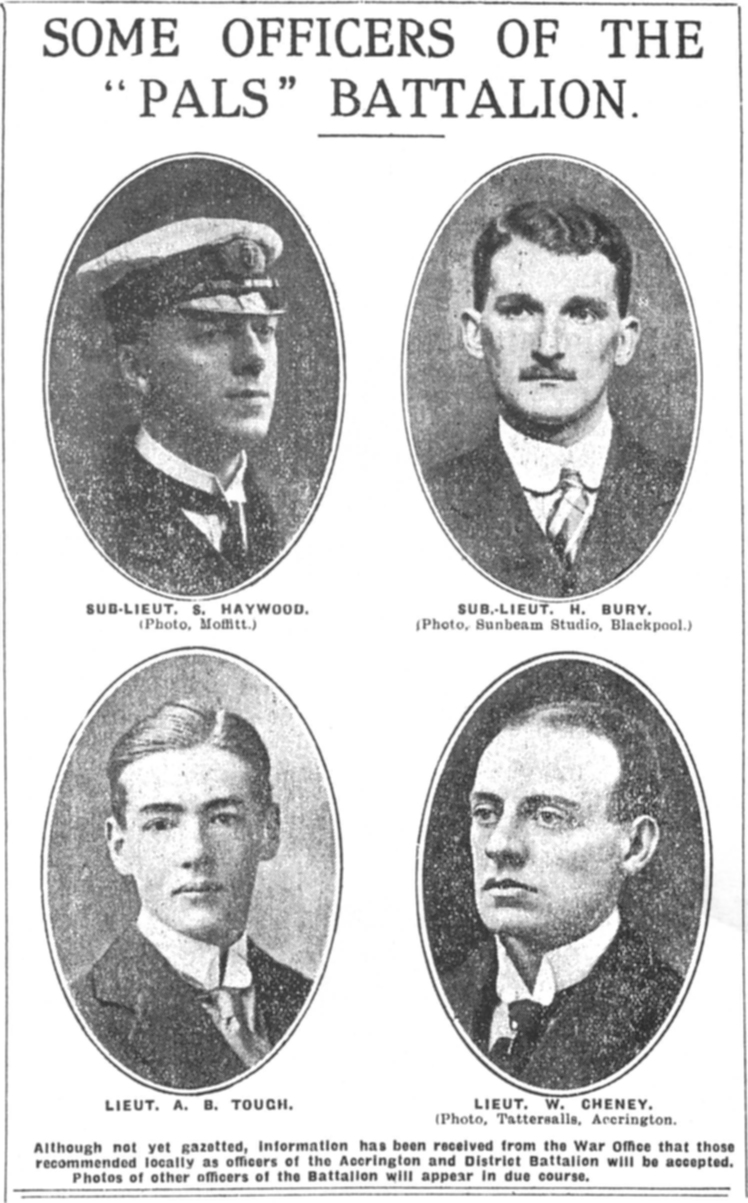

Candidates for commissions with the Battalion, however, went directly to Harwood. Twenty year old Tom Rawcliffe decided to leave the Accrington Company of Frontiersmen and enlist in the Battalion. His father, a Clayton-le-Moors cotton manufacturer ‘had a word’ with his friend Harwood.

“I went to the Town Hall first thing next morning. It was just like applying for a job on the Corporation. I had a short interview with the Mayor (Harwood) and Colonel Sharpies. They must have liked me — I was in as a second-lieutenant, temporarily gazetted, of course.”

2/Lt. Tom Rawcliffe

The War Office, still limiting its involvement to the issue of directions, allowed Municipalities — “ £7 per man to provide two suits of clothing — if they undertake to do so,” paid no doubt from Miltons’ sanguine ‘bank account for an unlimited amount.’2 Knowing he had to provide for a thousand men for at least the next six months Harwood had no time to lose. Whilst still recruiting he advertised in the local newspapers for tenders to be submitted, by September 22nd, from local firms to supply ‘clothing and accessories’ for the Battalion. The clothing included great coats, jackets and trousers in Melton blue and accessories ranged from kit-bags, toilet-requisites and eating utensils to socks, braces and towels.3

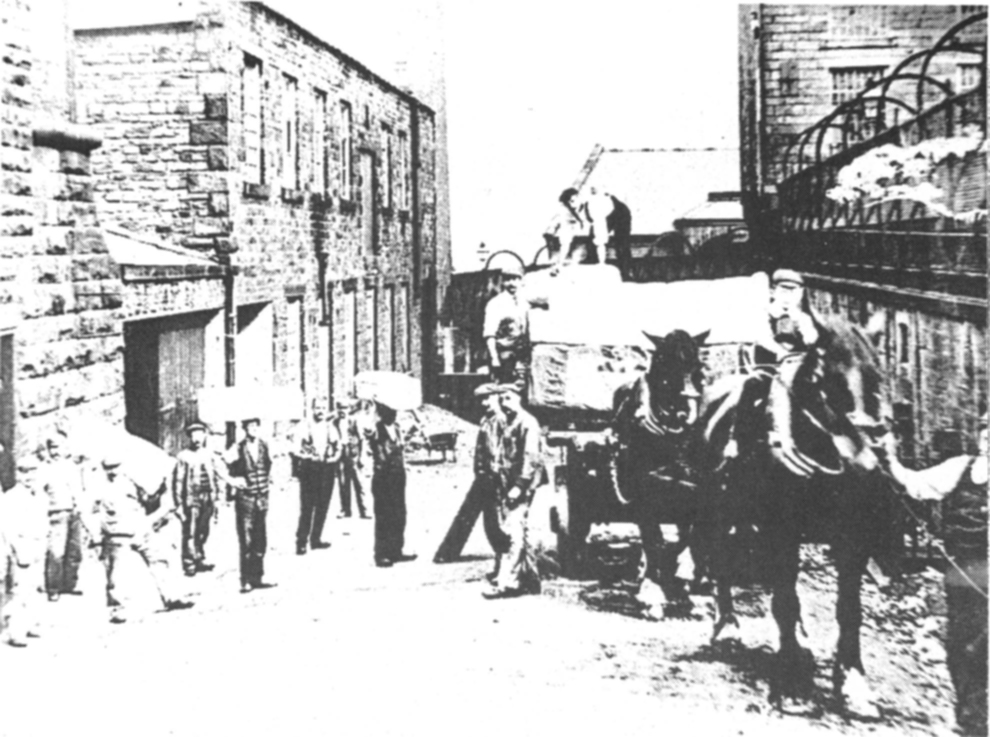

In 1914 the chief industries of the towns of East Lancashire were cotton weaving, mining and engineering. Many of the Pals worked in these industries before enlisting.

Labourers at a Burnley cotton mill load woven cloth for delivery to the major warehouses of Manchester.

Two weavers (left and centre) pose with a tackier (loom mechanic) before a typical ‘Lancashire’ loom.

L.L.B.D.

A group of miners underground at Duxbury Hall Colliery, Chorley. Note there are no safety helmets. There is however a Davy Safety Lamp on the leg of the miner in the foreground.

The pit-head and loading stages of Duxbury Hall colliery.

L.L.C.D.

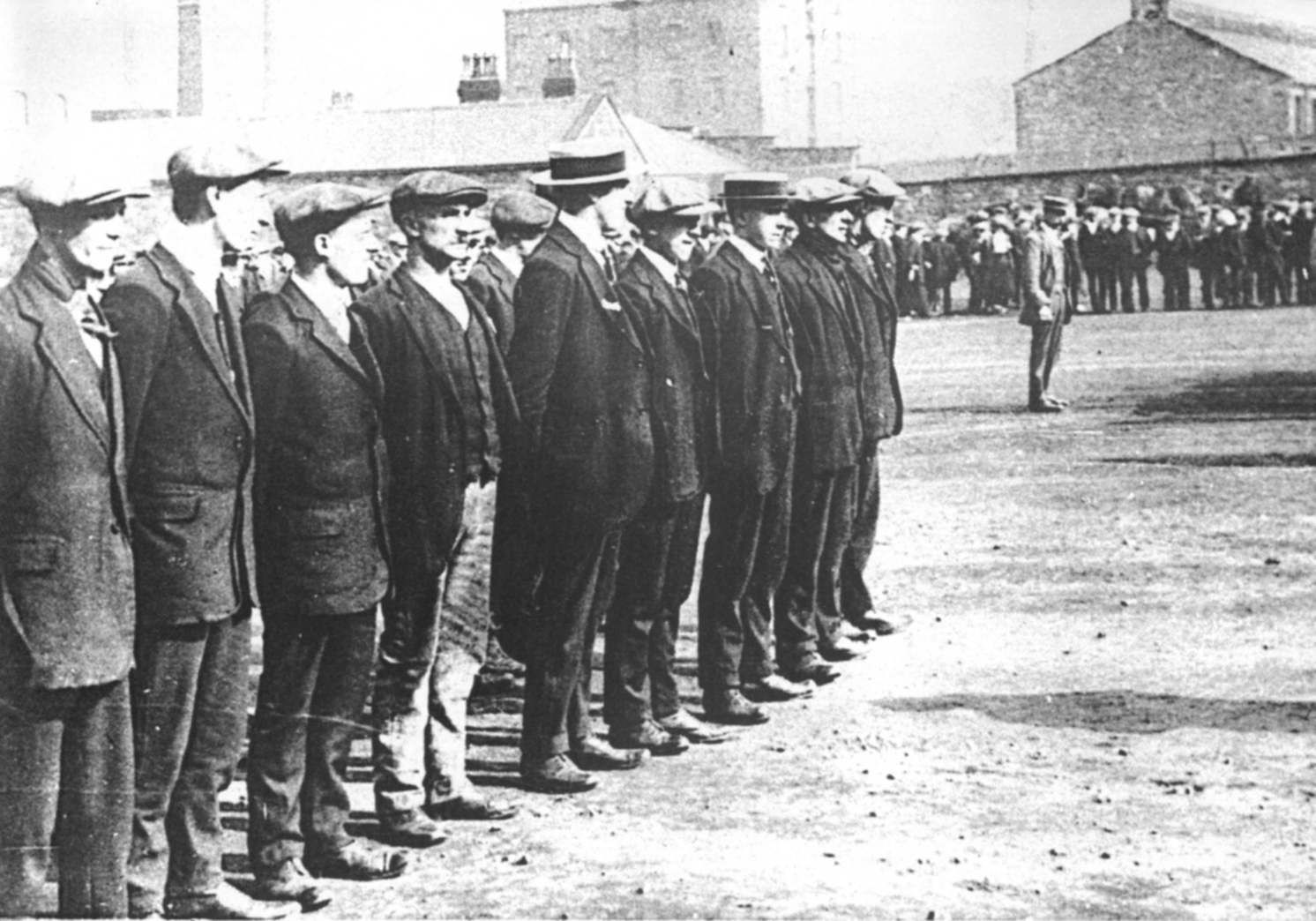

Pals awaiting orders to dismiss. On parade on Ellisons Tenement, Accrington on September 24th 1914.

“After forming fours a tremendous number of times, I presume on account of not doing it to the satisfaction of Major Slinger, we marched on to the Tenement. We continued forming fours. ‘Right, left and about turning’ until we were dismissed. Thus I received my First dose of military training.”

J. Bridge

“Tailors tendering for uniforms will be expected to measure and fit every man individually, guaranteeing a perfect fit.”4

With no time wasted after recruitment either, every morning newly enlisted men from Accrington and district assembled in the T. A. drill hall and marched to a public open space, Ellison’s Tenement, a short distance away, to be introduced to the intricacies of Company drill. R.S.M. Stanton, a 60 years old, who had answered the call for retired N.C.O.’s, instructed them.5 George Pollard enjoyed this period.

“I was in my element We paraded on the ‘Tenement’ every morning and afternoon. There were some, of course, who arrived for the afternoon parade after being in the pub at lunch time. We only had our civilian clothes to wear. Every day large crowds watched us parade, with so many not working there wasn’t much else for them to do. We weren’t used to marching so it was a bit of a shambles sometimes, especially when the Sergeant Major ordered ‘about turn!’ and some carried on marching! This always amused the onlookers of course and we became the daily entertainment for many. My platoon (Number 4, ‘A’ Company), did its physical training in Milnshaw Park (a small public park nearby) and here, as well as on route marches through the streets, crowds always watched us.”

The drilling and marching in public quickly brought comments from the onlookers. The first of many letters to the local newspapers complained about ‘the giggles of idle women and frivolous girls mixed with the sneers of supercilious men’ and suggested a guard to be put round Ellison’s Tenement to keep onlookers away. The ragged clothing worn and shoes and clogs of some marchers became noticeable, “- a man must be obtuse indeed if he did not feel what little self-respect he has is being lost by this public exhibition of poverty. I suggest these men are withdrawn and drilled while the rest are marching.”6 Harwood and Sharpies — and the men concerned — of course ignored the suggestion. Clearly, so early in its existence, the people of Accrington felt the Pals belonged to them, and with characteristic bluntness would never hesitate to praise or reprove them in print.

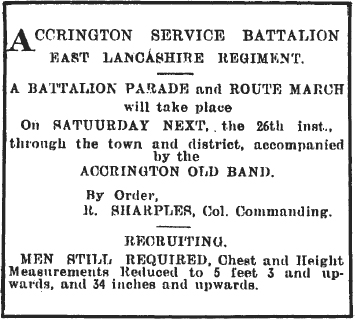

The advertisement placed in the ‘Accrington Gazette’ by John Harwood on September 12th, 1914. The chosen colour was melton blue.

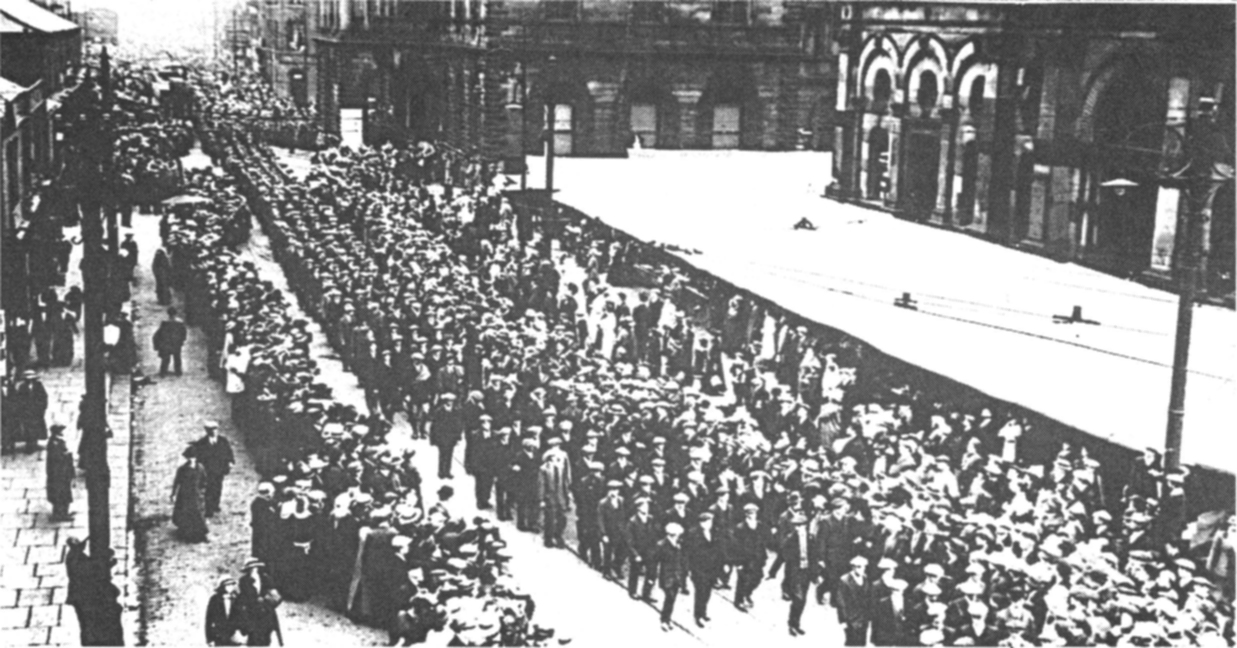

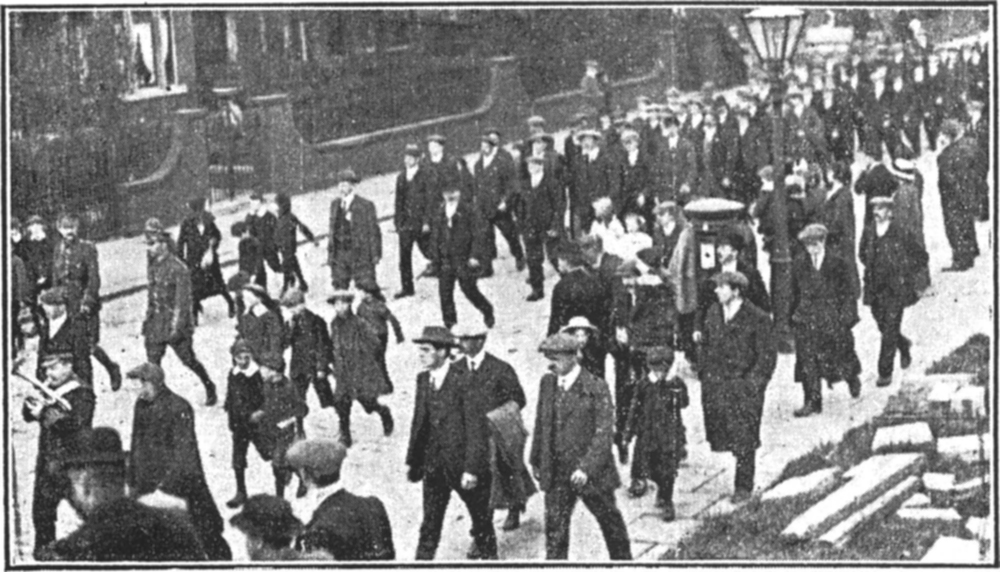

The first formal parade of the “Battalion” was a great success. ‘A’ ‘B’ and ‘D’ Companies assembled on Ellison’s Tenement at 4 p.m. on Saturday September 26th. (‘C’ Company, and its Blackburn Detachment, with Harwood’s blessing stayed at home). With ‘Accrington Old Band’ at its head, the three Companies, led by Sharpies, marched in a more or less military formation, four abreast, through the streets to the Town Hall. There the Band halted and played as the men, dressing in an assortment of smart or shabby clothes with headgear of either straw-boaters, trilbys or flat caps, marched past as Harwood took the salute. Thousands lined the streets as the Pals, rejoined by the Band, marched by a circular route around the town, back to Ellison’s Tenement.

The sight and sound of over seven hundred men, albeit in civilian dress, gladdened the heart of Harwood. He had raised a full Battalion for his town (although the compromises of Burnley and Chorley could not be ignored) and he had beaten his larger neighbours, Black-burn and Burnley. Accrington had already achieved distinction as the only non-county borough in the Country to raise a full battalion for Kitchener (not strictly true, the recruiting area was not solely in the town) Accrington enjoyed this prestige with much larger cities as Sheffield, Glasgow, Leeds, Manchester, Belfast, Cardiff etc. The legend of ‘little Accrington’ raising a thousand men had been born.

Harwood took the salute of ‘his’ battalion with all his hopes and ambitions realised. The Accrington newspapers, enthusiastic from the beginning, took a great interest in the ‘daily doings’ of the Battalion. The Accrington Observer and Times in editorial and feature columns attempted to dub the units ‘Accrington’s Own.’ This did not catch on — Pals was easier to say perhaps, and of course Burnley and Chorley would not have agreed. Nevertheless, local newspapers chose to refer to the Pals as belonging to Accrington alone, with only rare references to the neighbouring towns. The Observer and Times enthusiasm continued unabated. An edition carried a typical vignette: “I met a fellow of my acquaintance who is engaged in business in the town. ‘Well, I enquired, how is business in these uncertain days?’ ‘Oh,’ was the reply, ‘I’m not much concerned with business just now, I’ve joined the Pals, and now my chief end in life is drilling and marching.’ ‘And what does your mother think?’ ‘Oh,’ she’s quite proud of me, in fact … she was the recruiting sergeant.”7

Not all Accrington businessmen became so free from care. Those hopeful of a share of the advertised clothing contracts were very troubled. Hardwood’s purchasing policy had showed more of an eye for a bargain than support for local tradesmen. The first public protests, by a local bootmaker about the ordering of five hundred pairs of boots from a national wholesaler came in early October. At the same time, local tailors also learned of Harwood’s singular business methods.

On Saturday September 26th, 1914 the new battalion (except for ‘C’ [Chorley] Company) parades through Accrington.

Authors collection

It seemed Harwood, in a gentlemen’s agreement, promised local master tailors the clothing contracts on condition they cut their prices to the minimum. Nevertheless, he later told them he was about to accept a much lower tender from a Leeds firm of multiple tailors. Loud protests from the local tailors were met by Harwood’s offer to grant them part of the contract at the multiple’s price. This the locals could not meet. Profits and wages already were pared to the bone. In spite of private meetings and public protests Harwood awarded the contract to the multiple tailors. The economics of multiple tailoring and the business acumen of Harwood, combined to defeat local partialities. Although Mayor, Harwood gave no concessions to his businessmen ratepayers.

The resultant bad feeling and recriminations persisted in Accrington for many months. The high esteem for Harwood diminished among the town’s tradesmen. He had broken a gentlemen’s agreement, but worse still, allowed some three thousand pounds to go out of the town — a town desperately in need of work and wages. The quarrel also caused the issue of the blue uniforms to ‘A’, ‘B’ and ‘D’ Companies to be delayed until the early days of December.

No such problems arose at Chorley. Captain Milton, in a shrewd move, arranged with Harwood for ‘C’ Company’s clothing to be supplied locally. More mindful perhaps of good public relations, Milton appreciated the extra business would give a needed impetus to local trade. Approving this, the Chorley Guardian on September 19th asked Chorley tradesmen to return the favour by encouraging their employees to join the Pals. The Chorley-made uniforms were ready by the middle of October. A national shortage of brass buttons delayed their appearance in public until November 15th.

The advertisement for the parade placed in the Accrington Gazette on September 19th, 1914.

The blue melton uniform, although admired by the local population, was not particularly popular with the men. To them, the private soldiers dress of blue tunic, with red piping on collar and cuffs and blue trousers, looked suspiciously like a tram-drivers uniform. The N.C.O.’s, although adorned by wide gold stripes of rank on tunic sleeves, wore blue, peaked, ‘tram-drivers’ caps. The forage cap ‘special army pattern,’ of the private soldier needed adjusting with great care and skill for it to remain on the head. Weeks of wear and tear of civilian clothes in cold, wet weather made everyone pleased to get something — even though considered a stop-gap until the coveted khaki arrived. Chorley Company at least, with uniforms much better made with much better material, endured them with more grace than the Accrington and Burnley Companies.

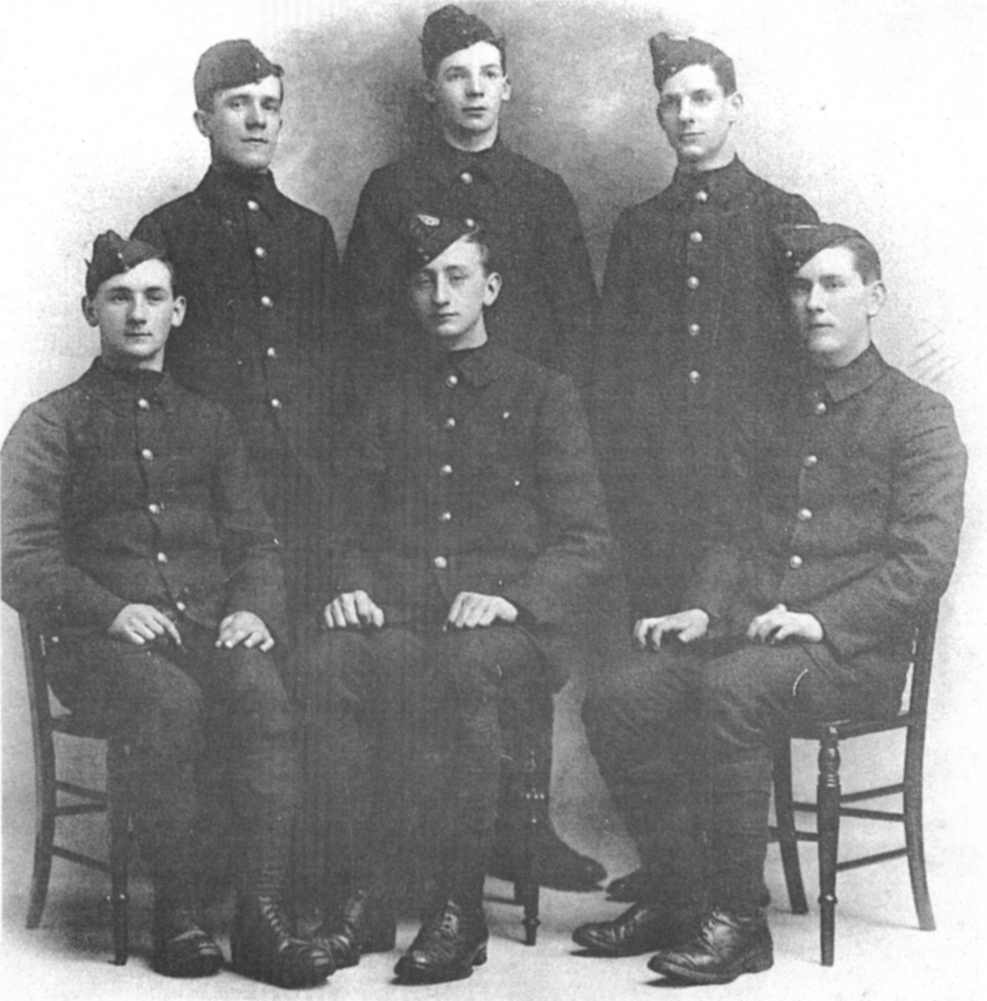

A group from St. Chad’s Roman Catholic Church Wheelton, near Chorley pose in the new uniforms.

J.Garwood

N.B. Pte. Wilfred Ellison (1st left rear) was to be the first Chorley Pal to die in active service. He died in France of untreated appendicitis on May 25th, 1916. (See page 124)

‘C’ (Chorley) Company parade for inspection outside the Technical College (now Chorley Library) in Union Street on Saturday December 19th, 1914. They are wearing the new melton blue uniforms for the first time.

Authors collection

Lance Corporal James Henry Woods ‘C’ (Chorley) Company.

Meanwhile training continued in the three towns. The newly issued training manual, ‘Infantry Training (4 Company Organisation)’ became required reading for ex-regular N.C.O., instructors and raw subalterns alike. The recommended six months training syllabus consisted of forty-two hours per fortnight on physical training, squad drill, musketry and lectures supplemented by regular route marches. The hours per fortnight increased gradually to fifty five and included platoon and company drill, field work (day and night) and entrenching as well as longer route marches. “The object to be aimed at in the training of the infantry soldier is to make him a better man than his adversary in the field of battle, — The preliminary steps necessary for the efficent training of the soldier are:-

i) the development of a soliderly spirit;

ii) the training of the body;

iii) training in the use of rifle, bayonet and spade.”8

From the beginning officers, N.C.O.’s, and men set about putting these principles into practice with lots of enthusiasm, energy and not a little lightheartedness and hilarity.

The ‘Accrington’ and ‘District’ Companies, led by Col. Sharpies, return from a route march over the ‘Coppice’.

A.O.&T.

The training in the winter months of 1914 and early 1915, formed the character of the Battalion. In this time all ranks strengthened existing friendships and made new, often life-long ones. The officers were already well known to most men, as sons of employers or men in public life. Some private soldiers, family men with sons as old as the younger subalterns, were not inclined to take seriously the orders of these callow youths, particularly when already acquainted with them in civilian life. There was no strong discipline in the manner of the Regular Army. The bases of spit and polish could hardly be imbued in men wearing civilian clothes who went home to their families in the evening. The Accrington Battalion shared this attribute with many other Kitchener Battalions. “In those great volunteer armies, discipline was a matter of the natural respect of the men, and their willingness to learn. The officer who found himself in charge of a thousand men had no means actually to enforce discipline — he would have been lynched if he had tried. But with any officer of any common sense, no need for enforcing discipline arose — at least no need opposed to that of the general instinct of the men themselves.”9 The Accrington Bat-talion, officers and men, wished to be soldiers, friends, volunteers together in their own home town company. The pride and expectations of their home towns bonded them together and formed their distinct qualities.

Full time training took over only gradually. For many, domestic and social routine changed little. Colonel Sharpies, even after his official appointment, on October 16th, as Lieutenant Colonel (temporary) of the Battalion, visited his solicitors’ office most mornings. Major Slinger (now Second in Command) and Captain Milton, as solicitors; Captain Watson as a General Practitioner; and Captain Broadley, in his family printing business; only gradually wound up their business affairs as training proceeded. Only Captain Ross, as an employee of Burnley Corporation, immediately served full-time with his Company. These six officers however with the sprinkling of ex-regular army N.C.O.’s, were the core of experience of the Battalion. Its junior officers were completely inexperienced as yet.

Captain Philip Broadley. Officer commanding ‘B’ (District) Company.

On parade on Ellison’s Tenement. Note the newly constructed tram depot in the background. In wet weather the Pals used the building as a drill-shed.

A.O.&T.

On November 4th, Harwood and Sharpies published their official list of officers. Local families prominent in the area’s business and social life were well represented.10 Harwood’s wide powers had allowed him to appoint as officers the relatives of business associates and magisterrial colleagues. He saw such appointments as an extension of the authority and leadership which their public standing had given them. This belief rationalised their appointment as officers. It is therefore not remarkable to see how closely the social structure of the Accrington Battalion mirrored the social structure of the town. Whatever the reasons for their appointments these youthful officers integrated into the battalion. Without exception their enthusiasm and readiness to take on any task quickly earned them the friendship and respect of the N.C.O.’s and men.

‘A’ (Accrington) Company, along with an assortment of children and spectators, march along Queens Road, Accrington.

A.O.&T.

In Burnley training quickly settled down. The Company soon found the T.A. Drill Hall too small so for most of their early drill practice they used nearby Bank Hall Meadow.”Here in the atmosphere of a Sunday School field day, in the fresh air and sunshine, blossomed the family spirit of the Company. A big crowd, all in little groups clumsily trying to learn squad drill from army training manuals.”11 As sections and platoons were formed men with qualities of leadership became N.C.O.’s. Anyone with service in the Regular or Territorial Army, Boy Scouts or indeed anyone who volunteered, gained promotion. On October 1st the Company moved to Burnley Barracks and Lt. Riley and Lt. Heys took over from Captain Robinson and Lt. Cockshutt of the T.A.

The newly appointed officers of ‘D’ (Burnley) Company. (Left to right) Capt. R. Ross, Lieut. J.V. Kershaw, Lieut. F.A. Heys and Lieut. H.D. Riley.

L.L. Burnley District

‘D’ (Burnley) Company drilling and marching on Bank Hall Meadow. Note (above) several Territorials temporarily attached to the Company to assist with drilling.

L.L. Burnley District

The Burnley Company spirit of irreverent enthusiasm soon evolved. Section rivalled section in keeness and platoon rivalled platoon. In contrast they responded only slowly to the strictures of the training manual. “The jigsaw was piecing together and now able to form itself into a square of four lines, each double. ‘Platoons.’ we heard them called. ‘Platoons!’ I thought those bloody things were for crossing rivers on!”12

Elementary military discipline did not come easily, “discipline was politely requested, by all, ‘The salute must be given to all officers.’ ‘What! off the parade ground?’ Many of the Company walked around street corners in town to avoid that salute, just shyness, said some. ‘Not bloody likely!’ said others. It was a long time before saluting came freely and in good style, but the leaders were men of understanding who had confidence and hopes for the best.”13

The Company, however, did begin to take training seriously. As early as September 21st seven mile route marches became routine. A typical week, for men in civilian clothing, was punishing by any standard. Starting Monday, November 16th, a 22 mile route march to Blackburn and back; Tuesday, drill parade, then baths parade at Burnley Public Baths; Wednesday, drill parade and a seven mile route march; Thursday, a 22 mile route march to Hebden Bridge and back; on Friday, drill parade and a five mile route march. Not surprisingly, they quickly gained a reputation for fitness and excellence in sports. The Burnley News commented on the number of excellent swimmers in the Company. “A few of the leading members of Burnley Swimming Club are in the ranks, and with members of Burnley Lads Club, this accounts for the good swimming to be seen at the Public Baths.”14

Their keeness and proficiency in marching also became known. Captain Ross bet the Accrington Company his men could march to Accrington and back in three hours. “Like a flash they were off, all on foot except Sergeant Kay, who drove his ambulance in the form of a motorbike and side-car, and saved his wind to sing ‘Cock-Robin.’ ‘Good luck, Bobby McGregor’ and ‘Tatty, will you go,’ etc. With the Captain in front and Ernest on his bike, blasting his songs into the ears of anyone showing signs of wearying, ‘D’ Company did it. The bet was won. Each man’s share of the bet was a bun and a bottle of pop.”15

The daily routine of the two Accrington Companies was no less arduous with the same combination of drills, marches and swimming. They also had their compensations. On the evening the Burnley bet was won, the Accrington Companies made a night march to Burnley. Tom Rawcliffe:

Visits to the Public Baths made a change from route marches and drilling. Here a group of Burnley Pals pose for the camera.

L.L. Burnley District

“We assembled outside Colonel Sharpies’ office in Avenue Parade at 8 p.m. He looked us over, then sent one or two home who had already had a pint or two. We set off for Burnley. It was a pitch black, moonless night and on the open road half way there, there were no lights at all. An order by Captain Slinger to halt went unheard by ‘A’ Company which disappeared into the darkness ahead. Moments later I heard, ‘Where the hell are ‘A’ Company, Lt. Rawcliffe?’ Don’t know, Sir, somewhere round the corner, I should say. ‘Well damn well catch them up then!’ However, we didn’t, but we all got to Burnley Barracks about the same time. What a welcome! Burnley were a most hospitable crowd beer and sandwiches galore. Perhaps a bit too much for some. We put one or two officers into taxis to get them home, and then we left to march to Accrington. Some of the men weren’t really capable of walking and we were a bedraggled, but happy, lot when we got back home.”

The following day, the Accrington and Burnley Companies, with the Blackburn Detachment, were formally inspected by Colonel R.J. Tudway, C.B., D.S.O., of No. 3 District, Western Command. During the inspection, so the story went, Colonel Tudway asked an Accrington man, ‘Did you ever drill before?’ He replied, honestly, ‘Yes Sir, I worked at Howard and Bulloughs.’ Colonel Tudway, when asked his opinion of the men, told the parade they would be pefectly capable of taking the field abroad in three months time. Whether this reply reflected Colonel Tudway’s honest view of the Bat-talion’s qualities is conjectural, but his words encouraged all in the Battalion. In six weeks a mob of men, unversed in military methods, had been shaped into an acceptable sort of order, enhanced by a quickly established camaraderie. The approbation of Colonel Tudway gave confidence to all in the Battalion.

The Accrington Companies were becoming the source of a fund of stories in the town. In bit-terly cold weather in late November, night exercises took place on the moors between Accrington and Burnley. The Observer and Times reporter, attached to ‘A’ Company, wrote, “The manoeuvring was reasonably well done and Accrington can rest assured every effort is being made to make the Battalion an efficient fighting unit. Comical events, of course happened. Wandering inhabitants were captured, trying to get through the lines and in one case, a relative with a small Lancashire Hot Pot for one of the defenders was seized. It is hoped the savoury and welcome dish reached its rightful owner.”16

The evening lecture in the T.A. Drill Hall became another element in the development of the men’s soldierly spirit and a source of other stories. The lectures were given by officers who themselves had scant knowledge of the subject. The men saw lectures as a relaxation rather than a serious part of training. Often their own views about the subject helped shape the lectures into a battle of wits.

Lt. Rawcliffe underwent the ‘ordeal.’ “A typical week’s lecture started on Monday with Lt. Roberts on the subject of ‘Belgium.’ Unfortunately someone unknown changed the slide sequence on the magic-lantern. His description of Bruges Cathedral accompanied by a slide of a steamer entering Antwerp harbour produced great hilarity. On Tuesday, Lt. Ramsbottom, as O.C. Battalion Scouts lectured to a rapt audience on ‘Scouting.’ On Wednesday, Colonel Sharpies and Captain Slinger (christened by the men, ever ready to apply a nickname, Mick and Mack, the crosstalk comedians) gave a joint lecture on ‘Co-operation in Warfare.’ I gave my lecture of ‘The History of the British Army,’ on Thursday, and because of my habit of standing with my hand tucked into my belt, I was quickly dubbed ‘Napoleon.’ They didn’t care if you heard them either! We officers didn’t bother, it was without malice. They didn’t always win the battle of wits. In his lecture on shells and explosives, Lt. Bury (Flash Harry, because of his smart dress) was asked, ‘Sir, what would happen if we were in a trench and a Lyddite shell dropped in?’ ‘You would never know, replied Harry, but your friends would read about it in the paper the next day.’ ”

As in Accrington and Burnley, training for the Chorley Company was a combination of squad, platoon and company drill in the mornings and field exercises or route marches in the afternoons. Lieutenants Gidlow-Jackson and Rigby gave the evening lectures assisted by the Accrington officers. Chorley Company visited almost all the neighbouring villages on their route marches and often combined the visit with a social event. On November 28th the Company marched seven miles to Croston, to be entertained to a potato-pie tea in the Wesleyan School by the villagers. The Company gave a drill display and played football against a village team, then marched back to Chorley leaving the ten Croston members to go home. A fortnight later, at Eccleston, five miles from Chorley, the Company attended a social and dance in the National School before returning to Chorley.

Placed in the Accrington Observer and Times, September 26th, 1914.

Whilst equal to the Accrington and Burnley Companies in their cheerful enthusiasm and dedication, the Chorley Company retained a more formal association with the town. Milton clearly believed in involving the Company in local social life and the townspeople reciprocated. The town’s civil and religious leaders, from the beginning, cared for the welfare of the Company. As early as September 20th weekly public church parades were held for C. of E. and Roman Catholic members, with Non Conformists attending their own chapels.

A service at St. Georges C. of E. on October 4th typified the spiritual concern for the men. One hundred and thirty six of the Company were each presented with a small, inscribed testament. The text of the service ‘For we be brethren.’ A month later, at St. Mary’s, each Roman Catholic member received a prayer book, a rosary, ‘a soldiers guide book’ and a medallion inscribed, ‘Our Lord, Mount Carmel.’17

In early November, the three Chorley officers’ wives set up a comforts fund for the Company and made a public appeal for gifts of socks, mufflers, body-belts, etc. News of the appeal disquieted several local Territorials then serving in Sussex. One wrote to the Chorley Guardian appealing for a similar comforts fund. He added “The men in the Pals are lying at home at night and do not feel the cold as we under canvas do. The only cry is for the ‘Chorley Pals.’ We are all fighting for one King, so why not let us chaps have the same honour as the Pals they seem to have it all at present.”18

A week later, an indignant ‘One of the Pals’ outlined some of the disadvantages of being a Pal. “Does he know we have been ten weeks without a uniform, whilst a Terrier already has a uniform? Married men have to keep a wife and family on the paltry sum of three shillings a day (21 shillings per week.) Understand we receive no separation allowances. So what have the Pals got? Nothing, except a small testament from St. George’s Church. Again, is he aware the East Lancashire Pals Battalion is one of the worse paid in the country? How is it a married man in the Salford Pals (15th Service Battalion,-Lancashire Fusiliers) gets 3/11d per day (27/6d per week) and those in the Manchester City Battalions, 7/6d for using their own overcoats? Men in Kitchener’s army in the South of England are compensated for clothing, wear and tear, whilst we receive nothing. How would you like to pay your own rail fare to go to your training, as a few of the Pals have to do?”19

Public airing of the Chorley Company’s grievances worked. Harwood, as paymaster of the Battalion reacted quickly and in the same week, the Chorley married men received 3/11d per day with back pay, for the weeks the correct pay scale had been in existence. It is a minor mystery why, when the pay-scales were already in force, Harwood had not voluntarily paid his men. The Territorials also benefited. The same week, 134 shirts, 132 mufflers and 506 pairs of socks were sent to Sussex by the Chorley Ladies Committee.

Burnley Company shared Chorley’s grievance over pay. Some men, disappointed with their pay and also anxious for active service, took their complaints to Mr. P. Morrell, Burnley’s M.P. On February 10th, 1915 Mr. Morrell raised the matter in the debate on the Army Estimates in the House of Commons. Referring to married men in local battalions who were billeted at home, he stated, “Many left excellent jobs in civil life and they are still receiving payment which compares very unfavourably with their civilian wages, and also with the pay of men training away from home. A soldier away from home pays his family 3/6d per week plus a separation allowance of 17/6d making £1 1s. per week. A man at home receives £1 1s. per week pay and billeting allowance. He gets 6/5d for light and fuel, so his wife has to keep him in everything on 6/5d per week. These men suffer from a double sense of grievance. They are willing to earn less than in civil employment, but they are receiving less than they would if they were away from home. They joined entirely from the highest motives and all they ask is to be sent away or have terms of service which corresponds with those who are away from home.” Unfortunately, Mr. Morrell’s question came too late. Two weeks later the Battalion left home and qualified for the separation allowance.

The criticism of the Chorley Company comforts fund did not affect the people of Chorley. Three weeks after their first appeal the officers wives advertised for furniture and other articles for a jumble sale and auction to be held in the Town Hall. A total of 1,079 articles was donated, making it necessary to divide the auction into three sections:- furniture, farm produce and clothing. Over seven hours of bidding and ‘knocking-down’ bought £85 14s 11d for the fund. The ladies were pleasantly surprised. In spite of the poverty in the town, people had responded very generously. In the same week 460 children had free meals in the Town Hall. Only four of Chorley and district’s forty cotton mills were working full-time. By a special irony, on New Year’s Eve 1914 the Canteen Committee of Chorley Town Council decided the Pals pay increase brought them above the minimum income of 26/- per week, so their children no longer qualified for free meals.

Two days after the C. of E. members received their Testaments, the Chorley Company received their first rifles. Two hundred, fifty per company, were allocated to the Battalion in early October. The Lee Metfords, relics of the South African War and before, were unfit for firing so were for drill purpose only. It also meant lectures on the elementary theoretical instruction in musketry of the Training Manual could now begin.

Chorley Company attended voluntarily, lectures of a different sort. When war was declared, Miss K. Knight, a French teacher at a Chorley school, as her patriotic duty taught French free of charge, to local servicemen. She offered her evening classes to the newly formed Chorley Company and from then on each evening taught the men elementary French. Phrases thought to be useful whilst on active service ‘Do you know which way our soldiers have passed?’ ‘Madam, I want something to eat as I am very hungry’ were taught. French speaking Belgian refugees and wounded soldiers helped with practical exercises. Miss Knight became a staunch friend and advocate of the Chorley Company and is still remembered with affection for her concern for them and their families. She died in 1948.

Christmas 1914 provided the first break in training along with the first opportunity for relaxation and entertainment. Celebrations started on December 19th, when the Accrington N.C.O.’s, repaid the Burnely N.C.O.’s, for their hospitality a short time before, with a concert and supper in the Old Black Bull. On December 23rd a more formal concert took place in Accrington Town Hall. Harwood spoke to a hall filled with ‘men and officers of the Battalion, officers wives and a few lady friends.’ He spoke of his pride in them and his confidence that they would do their duty in a manner which would bring credit to themselves and the town. A concert followed of which all the entertainers except one, were men from the Battalion. The evening closed with the presentation to each man of two pairs of socks, with the officers also receiving a khaki silk handkerchief, the gift of Mrs. Sharpies. The socks, twelve hundred pairs, were provided by the Accrington Pals Comforts Fund set up by Col. Sharpies’ daughter and the officers’ wives.

In Chorley, Miss Knight arranged two Christmas celebrations, the first, for her French class, on December 16th, the second, for all the Chorley Company on December 22nd. Local tradesmen supplied free food and drinks, and the Company members, with a few wounded Belgian soldiers, entertained with songs and monologues. The whole Battalion, in all Companies, appeared to have a wealth of musical talent in the ranks.

In the three main towns church parades and services were held. In Accrington, while the Roman Catholics went to Sacred Heart Church, four hundred men marched to St. John’s C. of E. Baxenden. Here the Reverend Mills, concerned as many were, for the moral and spiritual welfare of the men, appealed to them to keep themselves pure and sober. “They had the chance of a lifetime in going to the front”, he told them, but, “no man disregarded God when he was in the trenches with shells or bullets shrieking about him. It was then they needed religion, and plenty of it, but if they were right in their Christian faith, he had no doubt they would do great deeds.”21

It might be said, Harwood lost an opportunity to unite at least socially, the four Companies of the Battalion at Christmas 1914. For over three months, the Accrington Companies, with the Blackburn Detachment; the Burnley Company and the Chorley Company trained quite separately, albeit to the liking of individualists such as Ross and Milton. For them the opportunity had come to form and train their own company. Understandably, they were not inclined to share their company with anyone, however senior. The resulting quality of their companies showed their success. Harwood supported this view in a speech on his re-election as Mayor on November 9th, 1914. He had refused a War Office offer of £10,000 with which to build a barracks for the Battalion in Accring-ton. He believed the men would be better looked after at home, and so was content that the advantages of separate companies outweighed the disadvantages. Nevertheless, he knew Christmas 1914 would likely be the only one the Battalion would spend at home and the only opportunity to gather the whole Battalion together. In speeches, conversations etc. Harwood always referred to the two Accrington and District Companies as ‘the Battalion,’ so it is not surprising Accrington people believed this to be so. (Only the two Accrington and district companies were present at the ‘Battalion’ concert on December 23rd.) Happy in their semi-independence, the Burnley and Chorley Companies seemed not to hold any ill-will.

The Men’s Class of a Roman Catholic Church pose with their priest before the camera.

J.Garwood

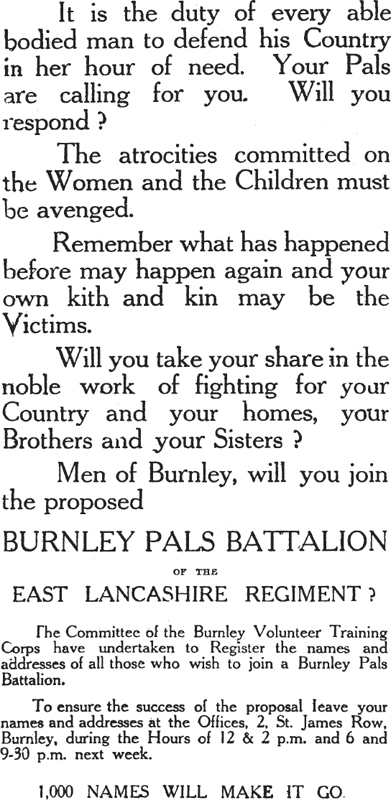

The attempted Burnley alternative to the Accrington Pals. This advert appeared in the Burnley News on November 28th, 1914.

L.L. Burnley District

Burnley Company’s part in civic life never achieved the prominence of Accrington’s or Chorley’s. They had no Mayor sufficiently interested to give them prestige, no Miss Knight to work on their behalf. Burnley had 106,000 population, the ‘Company’ but a small fraction of those who had enlisted. One Company of Pals in an Accrington battalion still rankled in a few hearts in Burnley. The weeks before Christmas saw an attempt to form a Burnley Pals Battalion. Letters in the Burnley News demanded the Mayor form such a battalion.22 The Mayor kept a diplomatic silence, leaving the enthusiasts to call their own public meetings. In spite of strong support by the local newspapers the idea, within a week or two, languished and died, killed by the realisation that official War Office sanction for raising Pals battalions ceased in September. The idea of Burnley’s own Pals battalion ended when sixty men who met weekly at Briercliffe, near Burnley to drill and Burnley Pals by name only, disbanded at the end of the year, their ranks reduced through enlistment. Although some Burnley folk did not like the idea, the Burnley Company of the Accrington Pals, was the only Pals unit in the town.

The Burnley Company, carefree as always, were too busy training to bother. In a night attack on Townley Hall (a 17th century house, set in acres of parkland) arrangements for ‘casualties’ to be inflicted were made. “After the first rush it was good to see what good marksmen the imaginary enemy really were. Half the defenders, evidently tired by their walk through town, died peacefully and were fast asleep ere the shouts of the attackers had echoed through the woodland.”23

On December 10th, 1914 the Fifth Army (37th to 42nd Divisions) was formed by the War Office. As a result the 7th (Accrington) Service Battalion became officially designated as the 11th (Accrington) Service Battalion, East Lancashire Regiment, and became part of 112th Infantry Brigade, 37th Division. The full complement of a New Army Battalion was now thirty officers and 1,350 men, including a new reserve company of five officers and 250 men. The War Office requested Harwood to recruit these at once. Recruitment for the new company designated ‘E’ started in Accrington, Burnley and Chorley on December 8th, 1914 and ended January 26th, 1915.

A group from No. 4 Platoon ‘A’ (Accrington) Company in Milnshaw Park, Accrington. Three were killed, one died of wounds and at least nine were to be wounded on July 1st, 1916. At least two in the Pals were only fifteen in 1914. One, Pte. Frank Bywater, stands third from left, back row.

The existence of ‘E’ Company meant some necessary re-organisation, four months had been hardly long enough for the ex-regular N.C.O.’s to train many junior N.C.O.’s. Miracles enough had been performed in getting the Battalion to its present standard. However, several barely-experienced lance-corporals and privates were promoted and transferred to ‘E’ Company to impart their military skills to the new recruits. At the same time, following Lord Kitchener’s recent recommendations that future commissioned officers should come from the ranks, five N.C.O.’s and privates were gazetted temporary second lieutenants. It so happened, four of them had a similar social background to those officers already serving:- Sgt. Williams, the son of a prominent businessman; Cpl. Ruttle, (on business in Japan when war broke out, he hurriedly returned to Accrington to enlist) the son of a local doctor; Pte. Slinger, son of Major Slinger; Pte. Whittaker, the nephew of Alderman Whittaker, Chairman of Clayton-le-Moors District Council. The exception was Lance Cpl. Kenny, a member of a theatrical touring company in Accrington in September 1914, and among the first to volunteer. The Battalion, now fully part of the New Army and up to full strength, was impatient to leave for active service. There was still some time to wait, mean-while the mundane tasks of training continued.

At the end of 1914, both the Blackburn Detachment and the Burnley Company became involved in controversy. On November 26th, passengers on the 7.55 a.m. Blackburn to Accrington tram complained of overcrowding. Many of the Blackburn Detachment used the tram, free, to attend morning parade in Accrington. Because of the complaints Blackburn Corporation decided men in uniform must pay tram fares. (How this would solve the overcrowding problem was not made clear.) The Blackburn men at once boycotted the tram service. Each morning, after assembling at the tram terminus, they marched the five miles to Accrington and marched back to Blackburn in the evening. The sight of ‘Kitchener’s volunteers’ having to march ten miles a day for the sake of a 4d tram fare each, incensed many of the public. Comparisons with Accrington’s free transport for five hundred men were made and in the face of such bitter criticism, Blackburn agreed to a special free tram for the Detachment, leaving at 8 a.m. and returning at 6 p.m. The boycott quickly ended. An arduous day’s training was quite enough without having a ten mile march added to it.

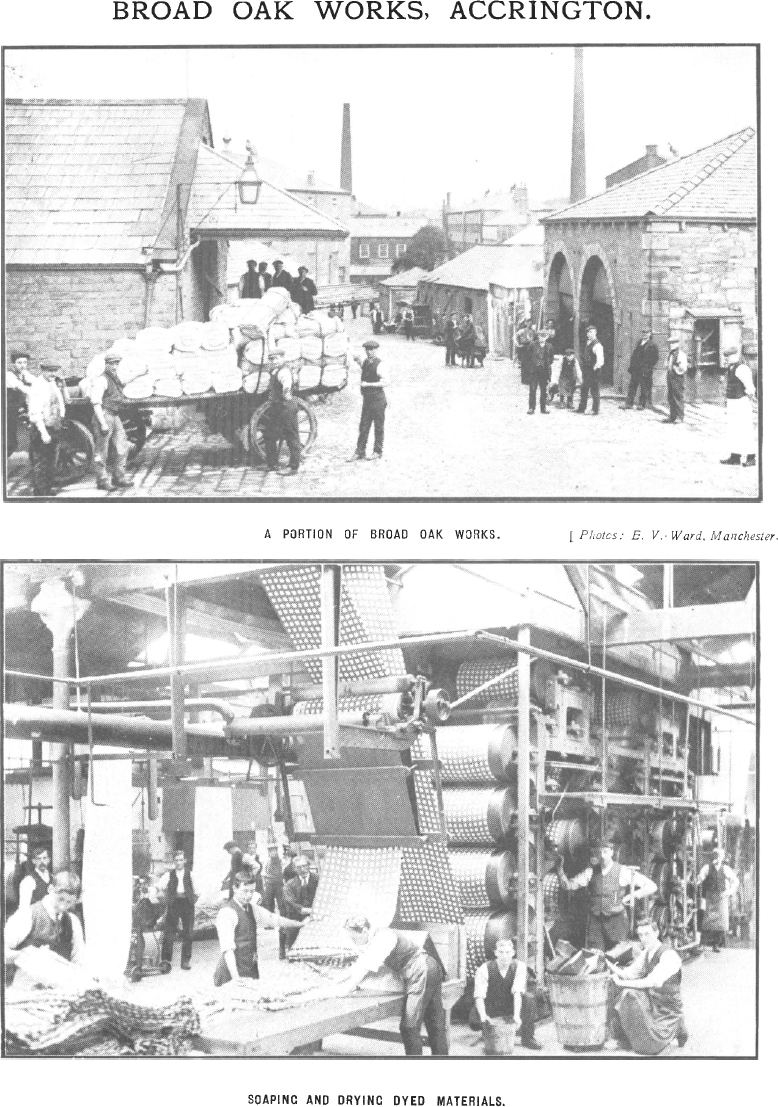

Many Pals were family men. Pte. Ernest Kenyon, age 37, of Accrington with his wife and young family. Before enlisting Pte. Kenyon was a calico-printer at Broad Oak works, Accrington. He was killed in action on June 23rd, 1916.

Calico printing was one of the chief industries of Accrington in 1914. A large group of employees from Broad Oak Calico Printing Works enlisted in the Pals. Pte. Kenyon (see previous page) was one of those presented to His Majesty King George V and Queen Mary when they visited the works on their Royal visit to Accrington on July 9th, 1913.

A. O. & T.

Only Blackburn had transport problems. The Accrington Companies, although some walked from their homes, travelled by tram from Church, Oswaldtwistle and Clayton-le-Moors. (The Rishton and Great Harwood men came by train from Rishton). From October 19th, when the fourteen week dispute at Howard and Bulloughs ended (one of the very few in the country to continue after the commencement of the war) the trams became much more crowded as over 3,000 men and boys returned to work. Sharing the journey were 300 ex-employees, now serving with the Battalion.

As the Blackburn controversy ended a different one began in Burnley. On the evening of December 3rd, Captain Ross and the Burnley Company were invited to attend free, the Palace Theatre, Burnley. The men, in their blue uniforms for the first time, were in high spirits. Even before the show began they entertained the rest of the audience with music-hall songs and encouraged the audience to join in the choruses. Understandably, the ‘military evening’ went down well. Encouraged, Ross arranged a visit to the nearby Empire Theatre. Here the professional musicians were on strike and had appealed to the public to stay away. Their protests about Ross’s ‘strike-breaking’ reached Mr. Arthur Henderson, Leader of the Labour Party, the Central Parliamentary Recruiting Committee and Colonel Sharpies himself. Mr. Henderson formally protested to the War Office against troops being paraded at places of entertainment at which there was a trades dispute, and angry Burnley trade unionists threatened not to help with future army recruiting.

Colonel Sharpies hastily visited the Burnley Company and the theatre finally arranging a ‘truce’ in that groups of men could not go but individuals could. The strikers final words were, “we have no objection to that if a Pal did not take another Pal with him”25 Ross’s action, from the best of motives the entertainment of his men succeeded only in bringing the Company, and the Battalion, to the unflattering notice of the War Office and threatened recruiting in the town. Even worse, in the eyes of some of his men, he had ended the type of night out they thoroughly enjoyed.

Messrs. Howard and Bulloughs Globe Works, Accrington. ‘Bulloughs’ as it was known in Accrington had a world-wide reputation as manufacturers of textile machinery. In normal times the street would be filled with men and boys as they made their way to and from work.

Men of the Blackburn detachment outside the Territorial Army Drill Hall in Accrington in September, 1914. The uniformed N.C.O.’s are ex-regular soldiers who re-enlisted to act as drill instructers.

A group of the Blackburn detachment in Milnshaw Park, Accrington, October 1914.

During those winter months the Battalion lost three men. Pte. Robert McGregor of Rishton drowned in the Leeds and Liverpool Canal in Rishton on November 9th. At the inquest the Coroner advised the jury, the deceased had ‘drowned himself whilst temporary insane.’ The jury disagreed and brought the more open verdict of ‘Found Drowned.” “The Coroner stated, That’s not in accordance with the evidence.’ The jury foreman replied, ‘I say it is, we knew him personally.’”26 How much the jury were influenced by McGregor’s membership of the Pals, is of course, conjectural. In Chorley, Pte. George Milton died at his home, of pneumonia, on February 1st, 1915. In Blackburn, Pte. John Brierley died at his home, also of pneumonia, the following day. Both men were buried with full military honours. Undoubtedly, the exceptionally cold, wet weather of January 1915, added to the rigours of trench digging, night exercises and route marches.

Times, however, were changing. After an inspection by Colonel Mackenzie of 112th Brigade on January 6th, 1915, speculation began about the Battalion leaving home. Inoculations against typhoid and the news of a plan to billet the Burnley and Chorley men in Accrington being abandoned added conviction. Further news of an inspection to be held on February 16th, by Major General E. T. Dickson, Inspector of Infantry, led everyone to conclude the Battalion’s imminent departure.

By this time, for some townspeople the novelty of troops in the town began to pall and attitudes were changing. Many local men had been on active service for some time. The 1st Bat-talion, East Lancashires, went to France on August 22nd, 1914; the 2nd Battalion in November. The 4th and 5th Territorial Battalions had been in Egypt since September. Chorley’s 1st Battalion, Loyal North Lancs, had also been in France since August 13th. Both 1st Battalions suffered heavy casualties and every week the local newspapers published disturbing letters from wounded men. Inevitably resentment arose; ‘Fred Karno’s Army’; ‘Petted Pals’; ‘Harwood’s Babies,’ were bestowed by those who believed they had ‘played at soldiers’ enough. Many of the men, sensitive to the criticism, wanted to go to the Front. As expressed by Burnley’s M.P., some had left good jobs to be less well paid than those away from home, so none were keener for active service.

In Chorley ‘One of the Pals’ wrote to the Chorley Guardian on January 30th, protesting against the, “insulting remarks of some Chorley inhabitants regarding the Pals not being drafted away we are all anxious to do our bit.” Support for the Pals came from the trenches. Bombardier Storey told a relative, “the man who comes out to France needs to be fully trained and then he needs his wits about him. So if perchance you hear any more unpleasant remarks about Kitchener’s Army please inform the bounders of the reason”.27

Private Walter Briggs of Accrington in the Melton blue uniform.

Sometimes the men themselves, in their irreverent enthusiasm, encouraged the critics. Lt. Rawcliffe:

“Sometimes we were not serious enough about the whole job. We Accrington officers lunched daily at the Station Hotel and one day we drank the health of some newly promoted second lieutenants. Time passed, of course, and when we eventually got to Ellison’s Tenement, a couple of hundred yards away, for the afternoon parade there were no soldiers there! Can you imagine it? We stopped passers-by to ask ‘Have you seen the Pals?’ Which way did they go?’ It seemed the Sergeant Major got fed up waiting for us and marched the whole lot off! We were a bit like Fred Karno’s Army at times, but nobody was happier!”

On Tuesday, February 16th, 1915, the day of Major General Dickson’s inspection, resentment and speculation vanished, the ‘bounders’ were to be satisfied. The formal inspection over and the General departed to Chorley, Harwood made the long-awaited announcement. He knew, he told them, they were anxious to leave the town and go into training elsewhere. “Now, he could say they were going, in a week’s time, to one of the brightest places on God’s earth, Caernarvon! (Cheers) The Battalion, at the suggestion of Colonel Sharpies, agreed to march through the centre of the town to give the townspeople an opportunity to see how well they looked.’”28

Major-General E.T. Dickson, Inspector of Infantry 1914-16

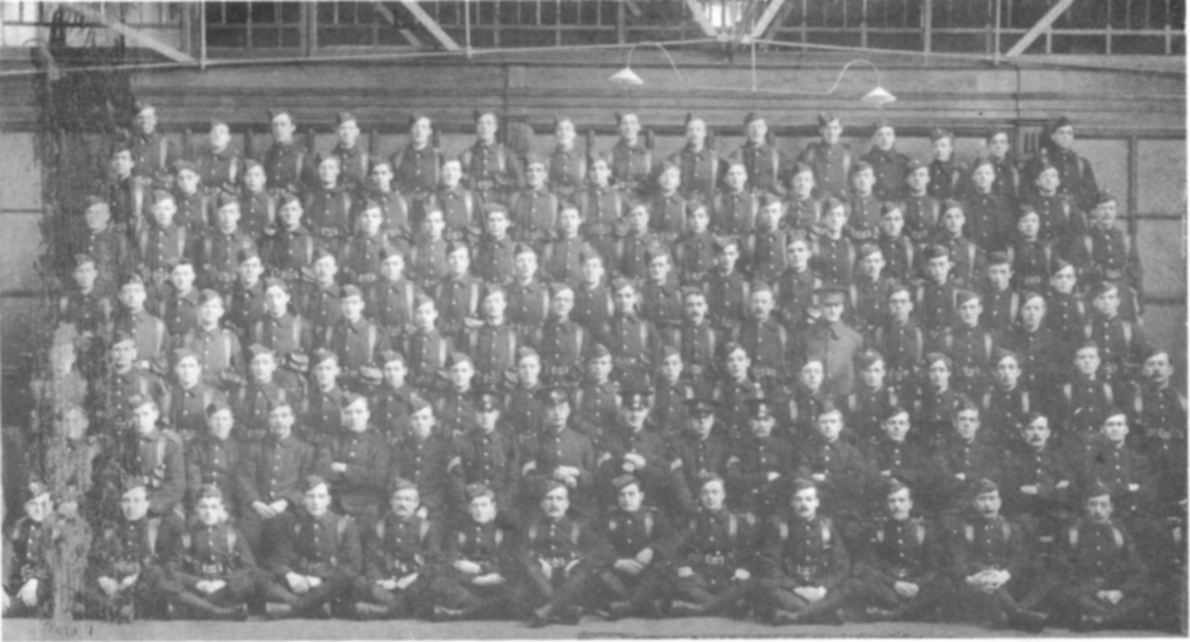

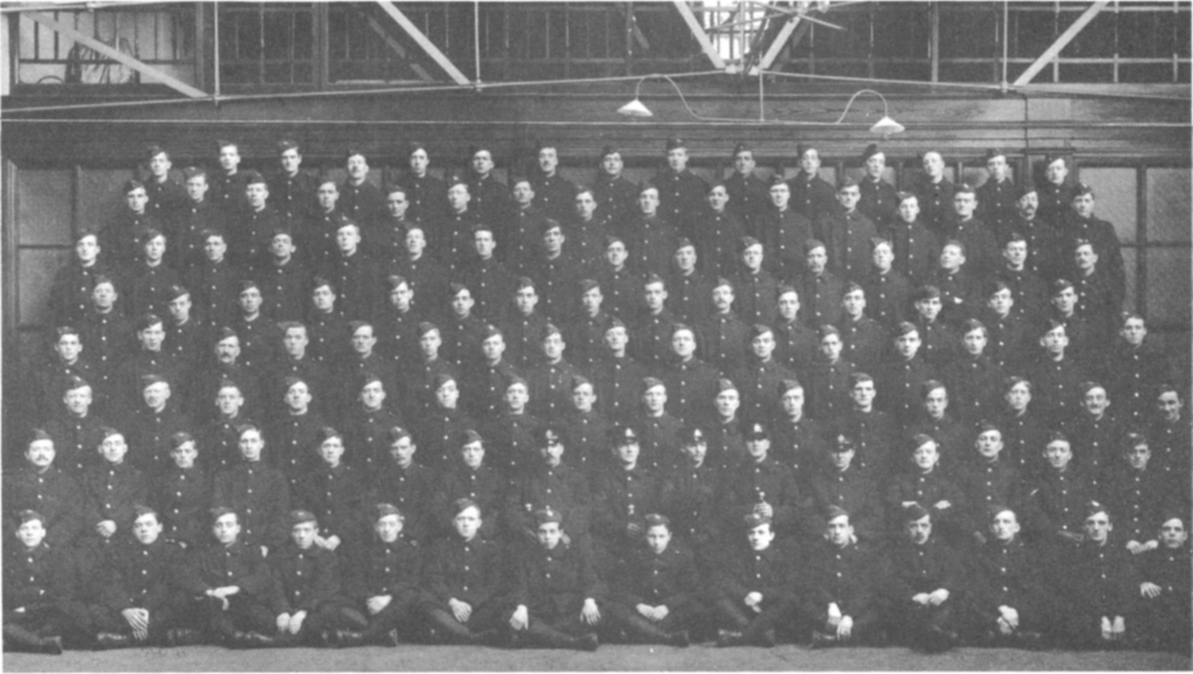

The Mayor of Accrington, Councillor John Harwood, J.P. with the Officers of the 11th East Lancs. Regiment (The ‘Accrington Pals’) February 1915.

Top Row (left to right) 2/Lt. J. Ramsbottom; 2/Lt. G. G. Williams; 2/Lt. W. Slinger; 2/Lt. C. D. Haywood; 2/Lt. H. Ashworth; Lt. C. W. Gidlow-Jackson; 2/Lt. F. Bailey; 2/Lt. W. R. Roberts. Second Row Mr. W. J. Newton (Accrington Borough Surveyor); 2/Lt. C. Stonehouse;2/Lt. T.W. Rawcliffe; 2/Lt. J.V. Kershaw; Lt. A. B. Tough; 2/Lt. H. H. Mitchell; 2/Lt. J. C. Shorrocks; 2/Lt. E. Jones; 2/Lt. W. G. M. Rigby. Third Row Lt. Campbell (R.A.M.C.); 2/Lt. F. A. Heys; 2/Lt. L. Ryden; 2/Lt. F. G. MacAlpine; 2/Lt. F. Birtwistle; Lt. T. J. Kenny; 2/Lt. T. Y. Harwood; 2/Lt. M. E. Whittaker;2/Lt. J.H. Ruttle; Lt. H. D. Riley. Front Row Hon. Capt. and Q.M.G. Lay; Capt.W.H. Cheney; Capt. H. Livesey; Capt. R. Ross; Major G. N. Slinger; The Mayor, John Harwood, J.P.; Col. R. Sharpies; Capt. J. C. Milton; Capt. P. J. Broadley; Capt. A. G. Watson; Lt. A. Peltzer.

A departure as early as February 23rd meant farewell parties had to be quickly organised. Chorley Company had two. At the first, a tea and concert, Milton (now Major) presented on the men’s behalf a leather travelling bag, with initials embossed, to Miss Knight. The second, in the Town Hall with the Mayor, the Town Council and many local employers and dignitaries present, was a more formal affair. In an evening of speeches in which the keynote was patriotism and devotion to duty, Milton, in keeping with his theme of spending War Office money in the town, said £742 12s. 2d had been spent with local tradesmen. He had also paid £5,276 8s. 9d in pay and allowances. Every single item of the Company’s equipment had been bought and paid for locally. He saw this as a small reward for the way Chorley treated them. The Chorley Weekly News commented, “The good wishes of the whole community will go with the Pals, the hope being they will remember the eyes of their native town are on them at all times.”29

Smaller townships bade their own farewells. Alderman Whittaker (Lt. Whittaker’s uncle) and Mr. J.H. Rawcliffe J.P. (Lt. Rawcliffe’s father) entertained the Clayton-le-Moors members of the Battalion to a tea and concert in the village Mechanics Institute, and each man received a pipe and an ounce of tobacco. Similar presentations took place in clubs, churches and chapels up to the eve of departure. Eight members of Oswaldtwistle Conservative Club received a hundred cigarettes each. Nine members at Rishton Conservative Club each got a pipe and tobacco and a khaki handkerchief with the flags of the Allies printed on them in colour. In Accrington, at Whalley Road Primitive Methodist Chapel, Ptes. Passmore, Proctor and Glover each received a Bible. “One would have thought the Pals were to sail straight for France and the trenches such was the fuss and palaver. Churches were crowded for valedictory services, at which sermons concentrated with extraordinary Christian unity on the dangers to the soldiers morals, rather than his life.”30

The official arrangements for Tuesday, February 23rd were for ‘A’ and ‘B’ company to leave Accrington at 9.15 a.m. ‘E’ Company and the Blackburn Detachment at 10.15 a.m. First parade 6.30 a.m. on Ellison’s Tenement to transport luggage etc., to the railway station, then breakfast at home and parade again at 8.30 a.m. At 9 a.m. headed by Slinger (now Major) and a fox terrier mascot, ‘A’ and ‘B’ Companies marched to the station. En-route, the crowds, lined six or seven deep, were surprised and disappointed to see there was no band. Several of the men taking matters into their own hands, started playing ‘Tipperary’ on concertinas or mouth organs. The march rapidly became more informal as men responded to the cheering crowds and shook the hands of friends. At least one man broke ranks, kissed his child and returned to his place. On the station approach mounted police forced a way through the crowd for the men to reach the station platform.

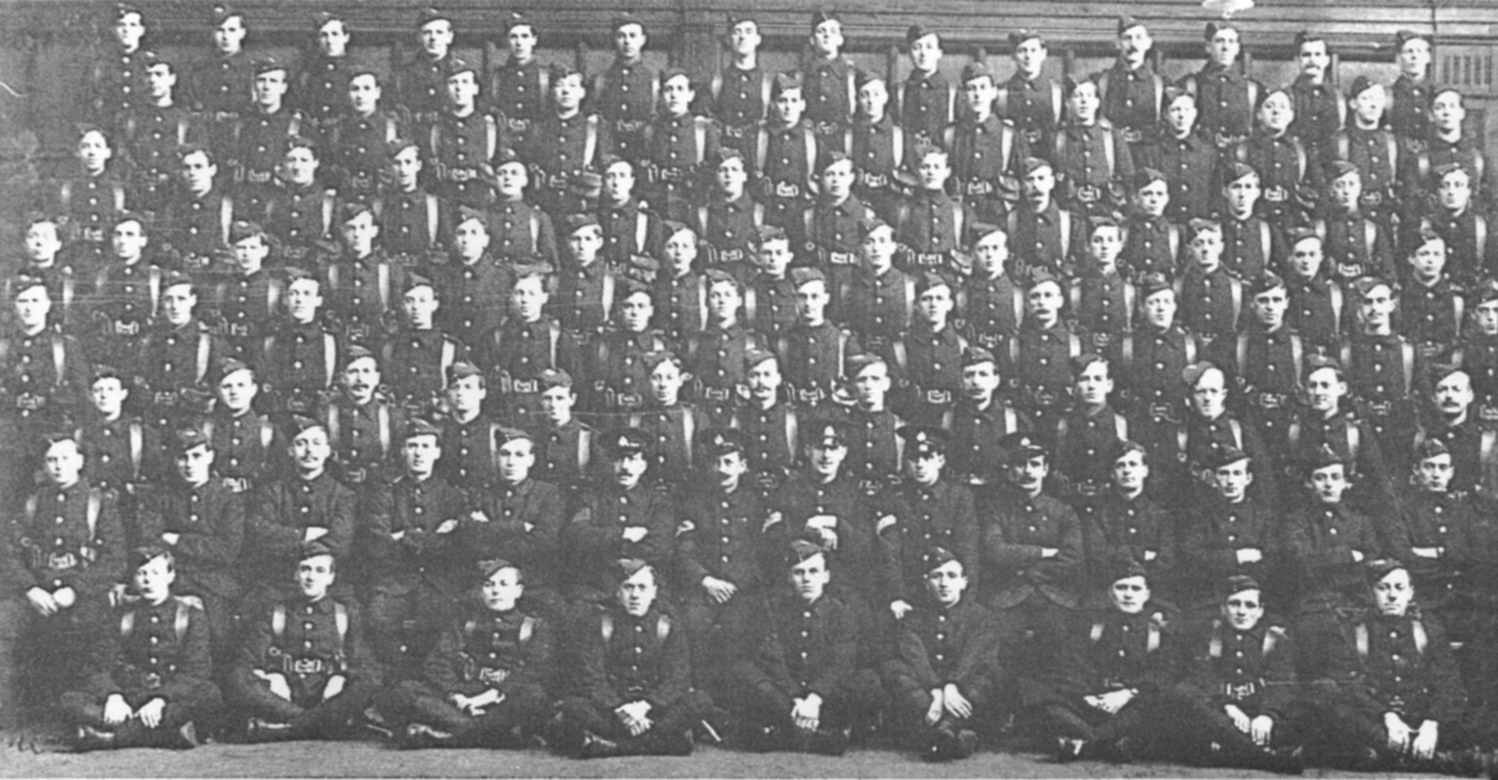

‘A’ (Accrington), ‘B’ (District) and ‘E’ (Reserve) Companies paraded in the St. John Ambulance Drill Hall for official photographs before leaving for Caernarvon (now Caernarfon) on February 23rd, 1915. Below are 3 and 4 Platoons ‘A’ (Accrington) Company.

Two Platoons of ‘B’ (District) Company.

Promptly at 9.15, ‘A’ and ‘B’ Companies left for Caernarvon, the men leaning out of the carriage windows to return the farewells of the crowd and Harwoods civic party. At Church and Oswaldtwistle station, half a mile up the line, crowds, including school children given the morning off, waved Union Jacks and cheered them on their way. An hour later the second train drew away to more farewells. After its departure the crowds waited in vain as it turned out for the advertised march of a second contingent not realising they had watched the whole contingent march past at 9 a.m. A misleading newspaper announcement had caused the crowd to believe that the two contingents would march separately to the station. The good humour of the crowd helped compensate for the disorganised manner of the leave-taking. “The event smacked of a public holiday. Many of the workshops and mills granted leave of absence, at other large works the employees took matters into their own hands and left without consent. It was a striking tribute to the Battalion that such a large crowd (estimated at 15,000) should assemble.”31

‘C’ (Chorley) Company on parade in the Territorial Army Drill Hall, Devonshire Road, Chorley in February, 1915. Col. Sharpies, Commanding Officer, on extreme left front row.

L.L. Chorley District

Burnley fared far better. At 10 a.m. the Company, led by Ross (now Major) and the bugles and drums of the T.A. Depot Company marched from the Barracks to the Town Hall. In the first civic recognition of the Company, the Deputy Mayor, Alderman Keighley, said “Burnley is proud of those who have volunteered to serve their King and Country in this hour of greatest need. I congratulate you on your smart appearance and wish you every success.”32 The formalities over, the Company marched through crowded streets to the railway station. They were given a ‘good send-off by the people and in true Burnley Company style they responded. “Plenty of cheers and tears and most of the men felt a fondness for their smoky old town for the first time. They sang cheerfully along Standish Street, but why it was ‘Wash me in the water that you washed your dirty daughter’, is past understanding. There were songs more appropriate, but there is no accounting for taste.”33 As the train drew away many men had mixed feelings, although good to be away, many left families to a world of anxiety and uncertainty.

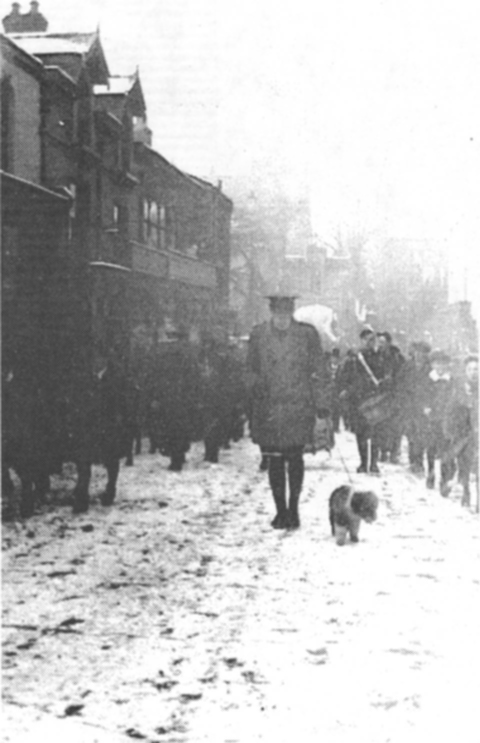

As the crowds in Accrington finally dispersed and those in Burnley gathered outside the Town Hall, the Chorley Company attended their private civic send-off in the T.A. Drill Hall. It was a celebration almost, the Chorley North Lancs Band played light music, and good humour abounded. The Mayor, in his speech, spoke inevitably, about his concern for their welfare away from home, then Mr. R. E. Stanton, a local businessman, in a mock-serious ceremony, formally presented to Milton a small terrier as a Company mascot. Milton, calling the dog Ned, after its donor, promised on behalf of his men to be ‘kind to the pet.’ He then called for ‘three cheers’ for the Mayor and Corporation of Chorley, followed by three cheers, amidst much laughter, for Ned. The Mayor thanked the men, amongst more laughter, on behalf of the dog.

At 11.20 the Company with Lt. Rigby and Ned at its head, marched to the railway station to the music of the Chorley North Lancs band. Although cold and wintry, with a light snow drifting down onto an overnight fall, crowds lined both sides of the route. Many in the crowd recollected it was fifteen years to the day since active service volunteers from Chorley had left for the South African war. All those men came safely home. It seemed a good omen. At the station a large crowd, including children excused from school, watched the Company march onto the platform. As they waited, the men, in a carnival mood, sang songs to entertain the crowd. The train, carrying Burnley Company, arrived at 11.50. Five minutes later, to the cheers of the crowd, to the sound of fog detonators on the line and the strains of ‘Auld Lang Syne,’ Chorley Company left for Caernarvon.

In Accrington the recriminations started, letters to the newpapers complained bitterly about the missing band and charged that its absence devalued the men and disgraced the town. All the local bands quickly pointed out they had always offered their services free for route marches, parades, etc., and each time were turned down by Colonel Sharpies. For his own reasons he kept to his ‘no bands’ policy on February 23rd. He might have reconsidered if he had known how deeply local people were affected that morning and in the days to follow. The controversy soon fizzled out, the Pals were gone and life had to continue.

The three towns settled back to normal life. All knew Caernarvon, in billets, did not compare with the trenches, but it did mean a step nearer active service and the Front.

2/Lt. W. G. M. Rigby, accompanied by Ned the mascot, leads ‘C’ (Chorley) Company up Chapel Street, Chorley, on the way to the railway station en-route to Caernarvon on February 23rd, 1915.

L.L. Chorley District

‘C’ (Chorley) Company marching along Chapel Steet, Chorley on their way to the railway station, February 23rd, 1915. Note the light snow fall on the ground.

L.L. Chorley District

Wives and dependents are now eligible for a separation allowance of 17/6d(87p) per week. Here wives in Burnley queue in the rain for their allowance books.

L.L. Burnley District

‘C’ (Chorley) Company on the march to the railway station (see preceding pages).

NOTES

1. A New Army Battalion consisted of four companies, 250 strong. Each company divided into four platoons, each platoon into four sections. The Battalion was commanded by a lieutenant-Colonel, with a Major as Second-in-Command. An Adjutant (Major) was responsible for administration, food, clothing, etc., Each company was commanded by a Major, assisted by a Captain; each platoon by a subaltern (Second Lieutenant) assisted by a Sergeant; each section by a Sergeant or Corporal assisted by a Lance Corporal.

2. See WO 163/44/M63 + M22 P.R.O.

3. Blue melton cloth, the traditional material for policemen’s, firemen’s and tram-driver’s etc., uniforms was in plentiful supply compared to khaki cloth.

4. Accrington Gazette (Hereafter A.G.) 12/9/14.

5. As a youth R.S.M. Stanton served with the U.S. Army in General Custer’s campaigns against the Sioux Indians. Later, in the Connaught Rangers he fought in the Zulu and South African Wars. He retired as C.S.M. in 1905. He died on March 2nd, 1915.

6. A.G. 26/9/14.

7. A.0.3/10/14.

8. Infantry Training (4 Company Organisation) General Staff. War Office, H.M.S.0.1914 Page 1.

9. The Kitchener Armies Page 141.

10. Typical examples include:- H. Livesey, Blackburn engineering firm director (Harwood was Chairman of the Company); A. Peltzer, the son of Howard and Bulloughs Company Secretary; A.B. Tough, the son of Accrington Medical Officer of Health; W.R. Roberts, M.D.; H.D. Riley, secretary and founder of Burnley Lads Club and J.P.; J.Ramsbottom, son of a leading building contractor; H. Bury, son of a Church chemical manufacturer and J.P.; T. Harwood, grandson of Captain Harwood; F.G. MacAlpine son of Sir George MacAlpine, colliery and brickworks owner, past Mayor and J.P.; J. Heys, son of a Burnley cotton manufacturer and J.P.

11. History of Z Company Page 2.

12. Ibid Page 2.

13. Ibid Page 3.

14. B.N. 21/11/14.

15. History of Z Company Page 4.

16. A.O.T. 28/11/14.

17. Genesis, Chapter XIII Verse 8 ‘and Abram said unto Lot, Let there be no strife, I pray thee, between me and thee, and between my Lordsman and thy herdsman, for we be brethren’.

18. C.G. 21/11/14.

19. C.G. 28/11/14.

20. Hansard, 5th Series, Volume LXIX, 10/2/15.

21. A.O.T. 15/12/14.

22. B.N. 28/11/14.

23. History of ‘Z’ Company Page 4.

24. The 24th (Service) Battalion, Manchester Regiment (Oldham Pals), 11th (Service) Battalion, South Lancashire Regiment (St. Helens Pals) and the 11th (Service) Battalion, Border Regiment, (The Lonsdales) made up the rest of 112th Brigade.

25. B.E. 30/12/14.

26. A.O.T. 21/11/14.

27. C.G. 6/2/15.

28. A.G. 20/2/15 (N.B. Modern spelling Caernarfon).

29. C.W.N. 20/2/15.

30. History of the Accrington Pals Page 30.

31. A.O.T. 27/2/15.

32. B.N. 24/2/15.

33. History of ‘Z’ Company Page 6.