Chapter Four

Some Battalion! Some Colonel!

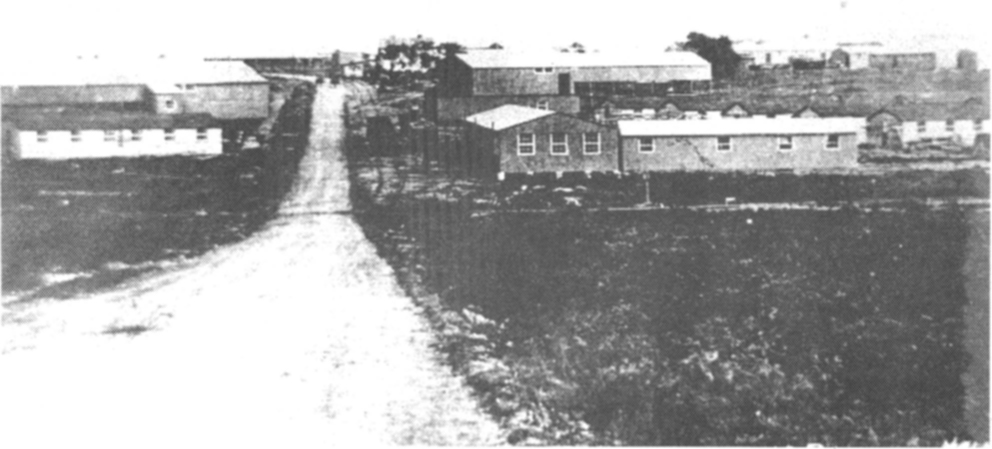

In August 1914, only 175,000 men could be accommodated in military barracks. By December 1914, over a million had enlisted and accommodation problems became acute. 800,000 men were housed in hired buildings and billets and mustering men from billets scattered over wide areas, as in Caernarvon, was irksome and inefficient for training at Battalion strength and impossible at Brigade and Division. In the winter of 1914 and the spring of 1915, therefore, dozens of hutted camps were hastily erected throughout the British Isles, each camp designed to house an Infantry Division (18,000 men).

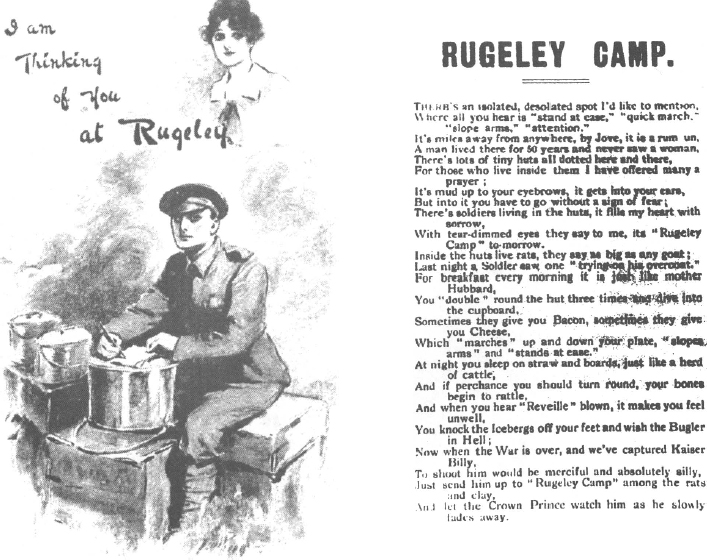

In addition to new camps in the established military encampments of Aldershot, Catterick and Salisbury Plain large open spaces in non-military areas were used, e.g. near Ripon, York-shire; Kinmel Park, North Wales and Prees Heath, Shropshire. Two others, Rugeley and Brocton Camps, were on adjacent sites on Cannock Chase, the ancient Royal hunting forest in Staffordshire. Rugeley Camp’s first occupants were the newly formed 94 Brigade, 31 Division.1

Moving in on May 12th, 1915, the advance party of the 11th East Lancs. Battalion found, as at Grantham, nothing ready. Many huts were roofless with no lights and no water within half a mile. With a dozen or so civilian joiners to help them, the advance party laboured a day and a night to make the thirty-man huts, the offices, stores and stables at least habitable. In the afternoon of May 13th, after a four and a half mile march from Rugeley station in pouring rain, the Battalion arrived to a welcoming lit coke-stove in each completed hut — and little else. At 8 p.m. the men ate a supper — the only meal of the day — of corned beef, bread and butter. Their tea, with neither sugar nor milk, was drunk from basins, jugs and whatever could be borrowed or stolen. Beds were just a straw palliasse on a board and trestles, with three blankets. The ablutions were in the open air, the camp a sea of mud, and chaos reigned supreme. The pleasures and comforts of Caernarvon were already but a dream. The realities of army life had begun.

Fine weather and drying winds quickly made camp life more bearable. Fatigue parties spent the first weeks improving roads, paths, and the water supply. Rugeley Camp and the Battalion along with it, rapidly took shape. Together as a unit for the first time since its formation, the Battalion specialist groups were organised. The regimental police, the transport, medical and sanitary sections came into being. Regimental cobblers and tailors were busy. The cookhouse, most important of all in most men’s eyes, started from scratch.

“We had been marching about an hour, but it seemed more like a day, when we saw ‘Hutments’. It might have been land in the middle of the ocean by the way the lads stared at it. We arrived absolutely wet through and we anticipated a drink of hot tea but alas nothing doing. It was the first taste we had of camp life and I can assure you it was a bitter pill to swallow.”

J. Bridge

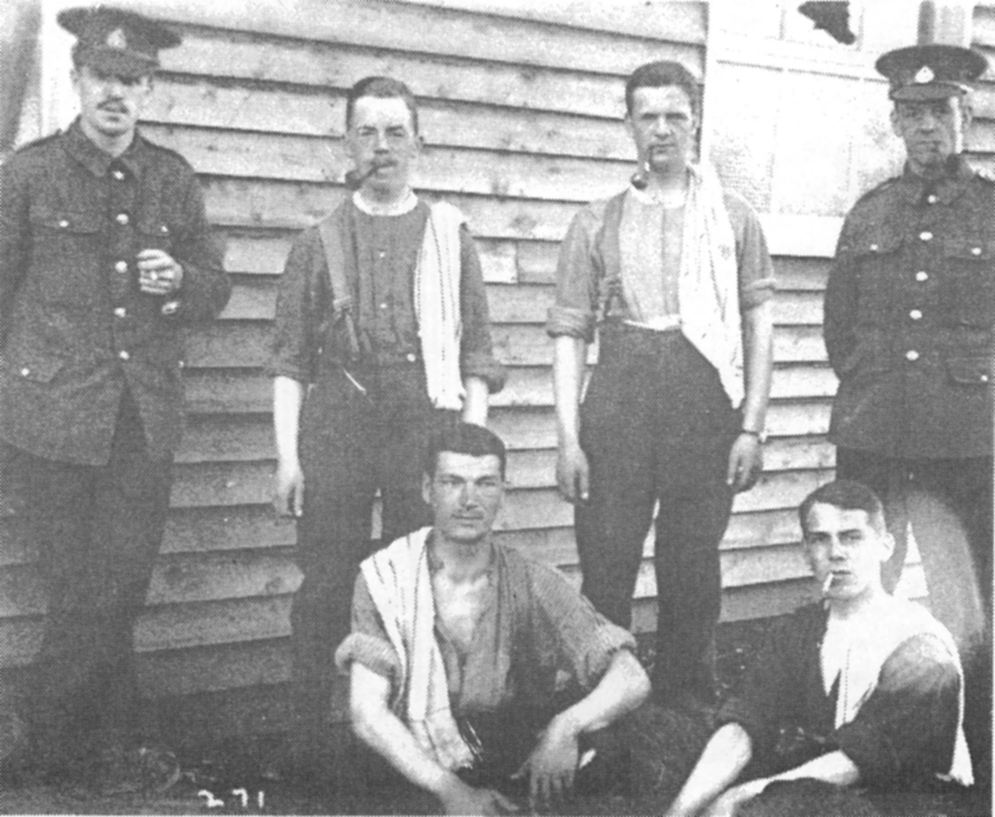

Men of ‘Z’ (Burnley) Company at Rugeley Camp. Note the civilian workmen.

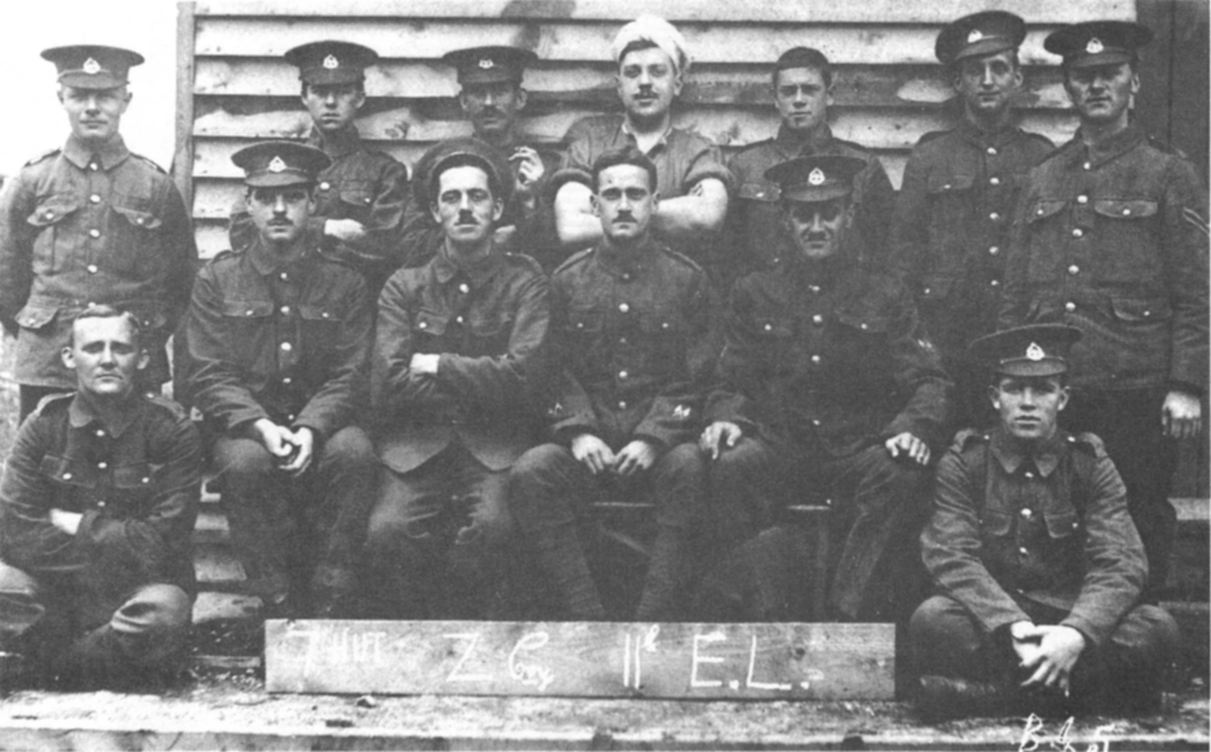

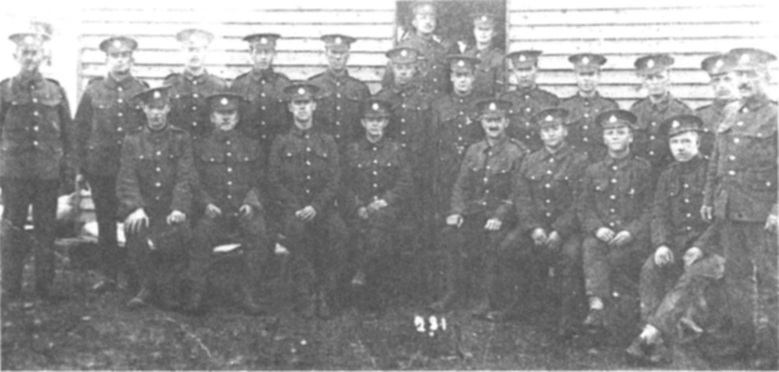

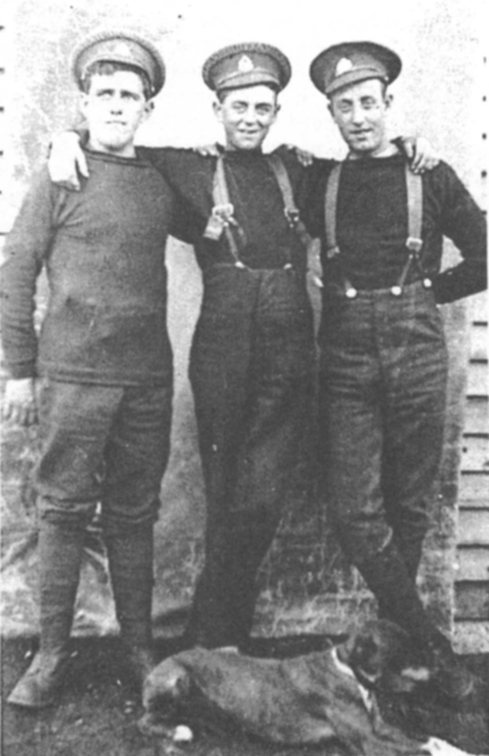

A group of ‘Z’ (Burnley) Company at Rugeley Camp. Of these men five were killed or died of wounds and seven wounded on July 1st, 1916.

Pte. J. Walton (second left, standing) of ‘Z’ (Burnley) Company with friends at Rugeley Camp.

No. 7 Hut ‘Z’

(Burnley) Company. Cpl. Holt (first right standing) in charge. Pte. Davy is third right standing.

Men volunteered, or if necessary were appointed as Sergeant Cooks, past experience not essential. Sgt. Clegg of ‘W’ Company, an ex-weaver, volunteered. Sgt. Kay of ‘Z’ Company, the motor-cycling corporal of early Burnley days did not. With the benefit of a short course in cookery they had the task of providing meals for hundreds of men. Their efforts were not always appreciated. “Some believed Sgt. Kay’s mind was still concentrated on internal combustion engines — but he was the persevering type and when one considers the cooks he had, it is a wonder anyone survived to tell the tale.”2

Others, including Pte. Marshall, took matters much more seriously. “Things were badly organised. Trouble started one day when we were very short of food. Some of us in ‘Z’ Company refused to parade at dinner-time in protest. We were then given a good meal. Later we were paraded and given a long lecture by the C.O. He told us we could have been shot for disobeying orders. A voice from the rear rank said, ‘Tha cor’nt do thad, tha’d shoot all your best sowdgers!’ With that, the matter ended.”3

The social and sporting activities of the Battalion continued. Pte. Coady, now in ‘W’ Company, with A.Q.M.S. Jack Hindle of Accrington, re-formed the Concert Party and Glee Club. A regimental Institute opened, with gifts of books and games from Burnley townspeople. Inter-Company football matches began. The Battalion football team (seven of whom were Burnley Lads Club members) with great pleasure consistently defeated the Yorkshiremen of the three York and Lancaster Battalions in the Brigade. Pte. Birch of ‘X’ Company whilst on home leave (fifty per Company per week) borrowed ‘for the duration’ the instruments of a local comic band. He re-formed the band on the returning train. The Battalion first knew of the existence of the ‘Pals Comic Band’ when it marched into camp at 2.30 a.m. playing The Bluebells of Scotland.’4

Training continued Caernarvon style — still limited by lack of specialist equipment — with Brigade exercises confined to continual route-marches. In the hot, dry, early summer of 1915, these tested the fortitude of many. As training progressed there were operational changes. On May 18th, the Battalion formally transferred from Western Command to join the three York and Lancaster Battalions in Northern Command.

Training intensified after the transfer. With no ammunition for the rifles, the bayonet remained the main weapon. The battalion learned how to form section, to advance and deploy in section, then push home a mock attack against one of the York and Lancaster battalions with the bayonet. At night the exercise was complicated by the total darkness on the open lands of Cannock Chase. Exercises often ended in total confusion as even sections lost touch with each other.

“Here we received our Brigade training. Route marching with the fullest of real training and at the finish moment, including attack and defence manoeuvres all along the moors. With so many troops passing over the heather the dust rose in clouds and when the lads returned they were covered in dirt. The lads settled down to real training and at the finish they became to somewhat like Rugeley Camp.”

J. Bridge

Rugeley Camp, 1915.

General views.

Parade ground and offices.

The battalion helped build an assault course made up of a series of belts of barbed wire and low hurdles. With the bayonet at the ready the men charged down the course, bridging the barbed wire with planks. After clearing the hurdles they charged and bayoneted ‘Gerry’ — still a bag of sawdust. Although the enemy had changed these were still the tactics of the South African War.

Three weeks after the transfer, on May 31st, every available man paraded for the acceptance of the Battalion by the War Office. The Army Ordnance Department first closely inspected the camp, equipment, clothing, stores etc. of the Battalion. The ‘camp-correspondent’ of the Accrington Gazette later described the acceptance ceremony. “All the officers and men were on parade, and after expressing his satisfaction in all he had seen, and with the smart appearance and bearing of the men, the War Office representative ceremoniously walked down the lines and touched one man in each platoon on the shoulder, thus formally claiming them as soldiers of His Majesty the King.”5 From that moment Harwood became officially free of the responsibilities, however nominal by then, as Raiser of the Battalion.

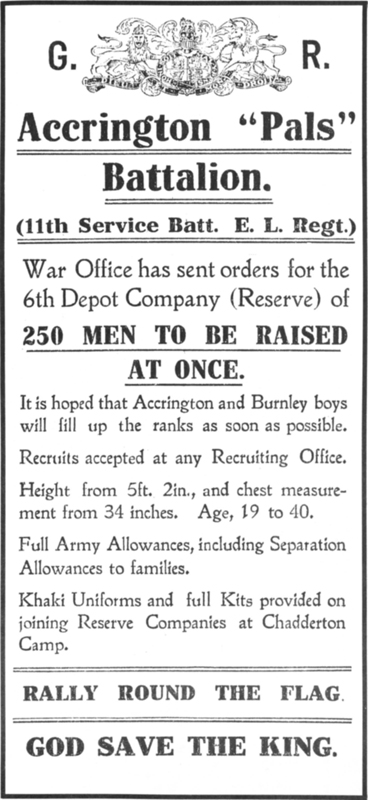

These developments convinced the men they were fit to go to the front. News also of a War Office request to Harwood, although not now officially connected with the Battalion, to raise a second reserve company of 250 men, convinced the men they were to go.6 Ever since the formation of the reserve company in December 1914, there had been a common belief in the Battalion they would need a second reserve company before the Battalion went abroad. With this news the men were convinced and many wrote home, prematurely, for what they thought was the last time.7 In spite of their own beliefs however, the men needed more training before they were fit for active service — their time at the front was yet to come.

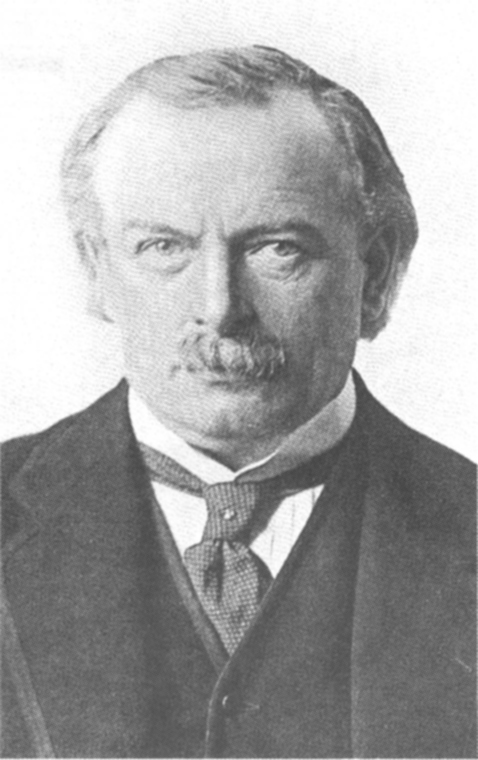

The Rt. Hon. David Lloyd George. In July 1915 he became Minister of Munitions. B.C.P.L.

‘The Comic Band’. Men of ‘X’ (District) Company dressed in the uniform of ‘The Village Pirate Band’.

With the Battalion an official part of the New Army, Rickman continued his efforts to make ‘his’ Battalion at least the best in 94 Brigade. Although tolerant of the ‘Comic Band’ for its entertainment value, he knew, as a regular soldier, a Regimental Band would be a more dignified acquisition. A good Band would be a prestigious possession, a morale booster and an entertainer. At the sugestion of Sgt. Ashmead of ‘W’ Company, a well known local bandsman and instructor to the Battalion’s buglers, Rickman contacted Harwood and within days a complete set of instruments, some new, some borrowed from Howard and Bulloughs Works Band, were provided by Sir George MacAlpine, and a group of anonymous donors.8

‘W’ (Accrington) Company at Rugeley Camp.

Company officers. Left to right: Lt.T.Y. Harwood, Capt. A. G. Watson, 2/Lt. H. Ashworth, Capt. H. Livesey and 2/Lt. H. Brabin.

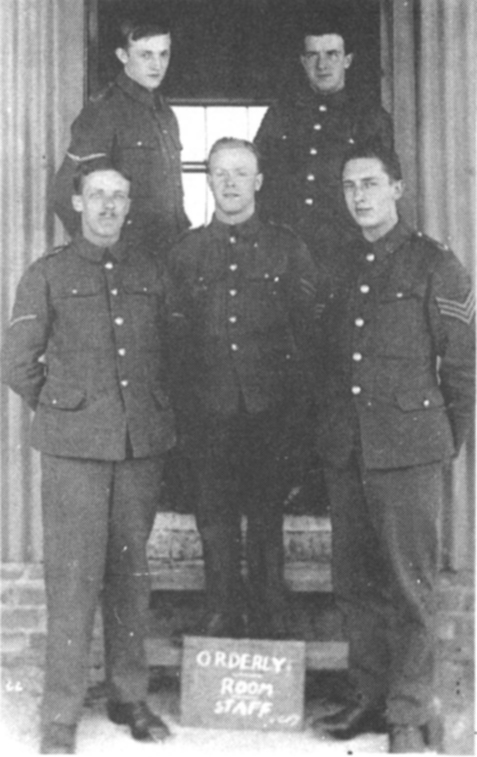

Orderly Room staff. Back row left to right: L/Cpl.Haywood, Sgt.J. Bridge. Front row: L/Cpl. Jackson, Cpl. Aspinall and Sgt. Hodgson.

Pte. C. Glover (second right) with friends.

Pte. V. Wardleworth (second right) with friends.

A more formal group including Pte. Harry Wilkinson (second left back row) and Pte. W. Clarke (fourth from left front row).

Twenty serving ex-bandsmen were anxious to join, with no lack of volunteers to fill the remaining places. Sgt. Ashmead, as an ex-Territorial skilled marksman, unfortunately was almost immediately posted to the School of Musketry, Hythe, as an instructor. Rickman therefore invited Mr. ‘Joe’ Whitworth of Chorley, to be his bandmaster, with the honorary rank of Lieutenant.9 After a little practice, the 11th East Lancs Regimental Band, the only band in the Brigade, proudly led the Battalion on the next Brigade route-march. “One moment it seems Col. Rickman was lamenting he had no band; almost immediately afterwards he had a band leading his men on the march.”10

Such developments firmly established the Battalion as a tightly knit unit. Men extended their loyalties from ‘their’ Company to ‘their’ Battalion and ‘their” Commanding Officer. Brigade exercises and sports promoted a friendly inter-battalion rivalry and a loyalty to ‘their’ Brigade.

As the Battalion improved in confidence and effectiveness, some thought the label ‘Pals’ gave an impression of ‘Saturday afternoon soldiers’ and so should be dropped, but most disagreed. Kitchener ‘Pals’ battalions, as a whole, had already gained themselves a good reputation. In contrast to the ‘happy-go-lucky’ impression of some, the Kitchener volunteers were turning out to be of a surprisingly high quality.11 For the 11th East Lancs, admittedly, compared to conditions at the front, the happy-go-lucky impression may have been reinforced by the mixture of training and recreations at Rugeley Camp as Rickman continued his policy of using as much sport as possible to supplement training.

‘W’ (Accrington) Company at Rugeley Camp. A variety of headgear is a feature of this group. Pte. C. Glover stands first left.

Sgt. J. Rigby stands in the doorway. Pte. H. Bloor is second left back row.

‘Z’ (Burnley) Company at Rugeley Camp.

The group includes Pte. J. Power (with arms folded front row) and Pte. L. Bentley (in doorway, left, with monkey on his shoulder). Pte. Bentley wrote to the Burnley News on May 29th, 1915 requesting help in obtaining a replacement for the monkey when it was accidentally killed.

Sgt. A. K. Entwistle (second night middle row) with some of his men.

Names not known. A chalked sign on the hut side states ‘Sweeny Todd, Barber. Rag-time or slow time. Next Please 2/6d (12p) each. Boston Barred.

On May 14th, 1915 after the British setbacks at the battle of Festubert the shortage of shells on the Western Front had been revealed to the public.12 The resulting ‘shell scandal’ contributed to the fall of the Asquith Liberal government on May 17th.13 David Lloyd George became Minister for Munitions in the new Coalition Government, with his first task to re-organise the munitions industry to meet the demands of the war. Already the one fifth of male workers in engineering serving in the forces meant a major shortage of skilled labour.

The 11th East Lancs had many such skilled engineers in its ranks. Most were ex-employees of Howard and Bulloughs who enlisted when the works closed in September 1914. In July 1915, many of these were interviewed by Ministry of Munitions inspectors under the ‘Bulk Release Scheme’ and returned to Howard and Bulloughs as munition workers.14 Others, as on July 12th, 1915, were drafted in small batches, direct to shipyards in the North East. At least 150 men, mostly from ‘W’ and ‘X’ Companies, left the Battalion under this Scheme.

In Accrington meanwhile, Harwood attempted to recruit a second reserve company. A detachment of fifty men from Chadderton, with the band of the 10th (Service) Lancashire Fusiliers, toured the area ‘buttonholing every young man they met.’ They had little success. In one disappointing week they enlisted just twenty-nine men — a sharp contrast to the heady weeks of September 1914.15 Clearly a second full scale recruiting campaign to get the second reserve company and also replace those lost to munitions work was urgently needed. The opportunity soon came.

As early as the first week in June, Rickman had been endeavouring to move the Battalion to South Camp, Ripon, in the West Riding of Yorkshire, for a musketry course. He intended to march the Battalion from Ripon to East Lancashire, accompanied by the band, over a period of eight or nine days and then recruit in the area for a few more days. Authority for the move did not arrive until mid-July so the idea had to be dropped. The campaign, therefore, had to be conducted on the way to Ripon, not from it. With this intention the Battalion left Rugeley at 4.20 a.m. on July 30th, by train to Chorley. With them travelled Pte. Joseph Bell, who only four weeks before returned as Cpl. Bell from Accrington under escort, absent without leave.16

‘Y’ (Chorley) Company at Rugeley Camp.

An athletic group pose outside their hut. Pte. W. Cowell is seated second from left, front row. Pte. L. Saunders fourth from right, front row.

A common feature of many group photographs was the symbols of kitchen fatigues. Pte. L. Saunders (in shirt) stands in the doorway.

A similar group with Pte. S. Rollins third from right back row.

J.Garwood

A group of the Reserve Company at Chadderton Park Camp, near Oldham, Lancashire. After the recruitment of the second Reserve Company to replace those released for munitions work in the summer of 1915 they became the 12th (Reserve) Battalion. Note the mascot — the seven-year-old son of a Sergeant.

A group of ’X’ (District) Company. Back row: Cpl. Duckworth, Ptes. J. Grimshaw, E. Kenyon and C. Hindle. (brother of J. Hindle, see front cover photo). Front row: Ptes. E. Culley, L. Kenyon and J. Hindle. Of this group one was killed in action on 20th June, 1916 and one on 23rd June, 1916. Two were killed in action and three wounded on 1st July, 1916.

Blank postcards as kept by Pte. W. Cowell of ‘Y’ (Chorley) Company.

“Time passed on and I at last heard we were about to make a move. I remember quite well parading at 3.30 a.m. one morning and marching to Rugeley Station. It developed into a beautiful morning and the lads were awfully jolly at the prospect of marching through Accrington again. People were peeping from behind the blinds, it being too early for them to be up”

J. Bridge

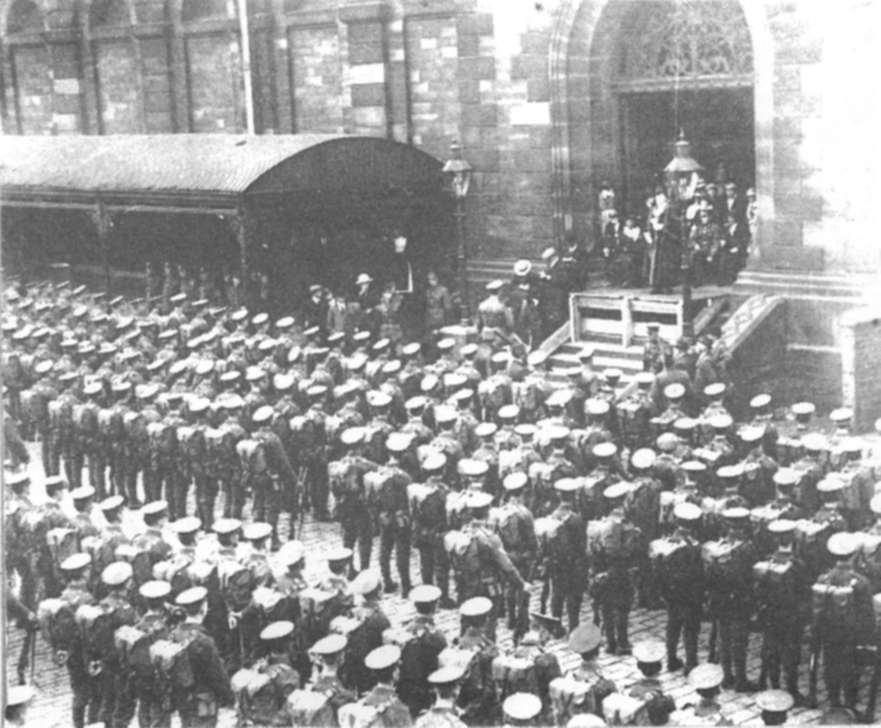

At Chorley, the Mayor, delighted Chorley was the first home town to welcome the full Bat-talion, accorded the men ‘a right hearty Lancashire welcome’ at a civic reception. With Lancashire candour he asked Rickman to take back with him “the shirkers on the street-corners” and asked the Battalion to “do its utmost to get the war over as soon as possible — we are all miserable and want it to end.” He then asked Rickman to give Chorley Company a day’s holiday “when it is convenient.”17 The next morning the Battalion marched seven miles to the Royal Lancashire Agricultural Show at Witton, near Blackburn. Here, as the main event of the day, they gave a drill display. Lt. Rawcliffe, newly promoted, led his platoon in a display of Swedish Drill (Physical Training). After an hour or so of entertaining and being entertained, they marched two miles into Blackburn and were allocated to billets for the overnight stay. Pte. Pollard and others, succumbed to the temptations of home.

“It was a beautifully sunny Saturday afternoon. After we were dismissed in Black-burn, we Accrington lads strolled on the Boulevard (the main tram terminus in front of the railway station) for a while, just to let the girls look at us, you know, and then caught the tram to Accrington and home. We came back to Blackburn the following day, then marched back to Accrington. The whole town turned out to see us”.

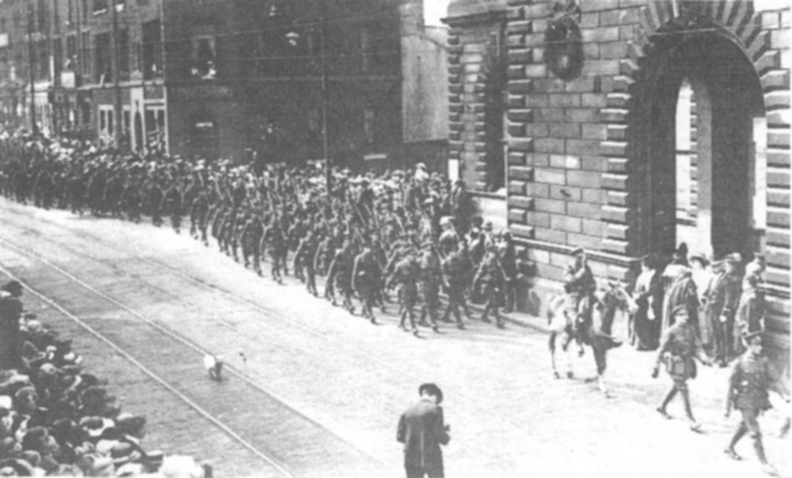

The whole town did indeed turn out. An estimated eighteen thousand lined the streets as John Harwood took the salute at the march-past in front of the town hall, the Battalion back in its ‘home’ town for the first and only time as a complete unit and for the first time in khaki. Six months training and discipline had made a tremendous improvement in their bearing, physique and self-esteem. They were proud in their belief that they were one of the best of the ‘Kitchener’ battalions and considered themselves the equal of any in the British Army. With the same old spirit they sang the same old songs. “It brought blushes to the faces of the young ladies out walking with their fellows when the massive choir blasted forth, ‘Hello, Hello, Who’s your lady-friend? Who’s the little girlie by your side?’ as they passed by on the road”18.

The Battalion stayed three days in Accrington for a programme of recruiting marches, drill displays and evening band concerts in the local parks. At a dinner given by Harwood and his associates for Rickman and his officers, Rickman spoke of his gratitude that he, a stranger who had never even been to Lancashire, had been supported so loyally by his Lancashire troops. He was very moved by his acceptance by the men, by his reception in the town and ‘absolutely astonished’ by the great number of people who had greeted them so warmly. This reception given to Rickman by the town, more than anything else, helped turn a formal association into a deep and lasting friendship sustained throughout the long, hard years of the war.

‘Y’ (Chorley) Company in Commercial Street, Chorley on the recruiting visit on August 1st, 1915.

L. L. Chorley District.

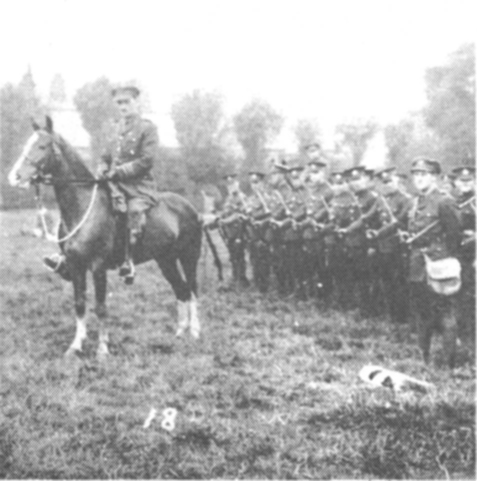

Major Milton and ‘Y’ (Chorley) Company in Coronation Park, Chorley. Note the mascot dog lying down.

The Mayor of Burnley, Ald. Sellers Kay, addressing the parade on the recruiting visit to Burnley on August 4th, 1915.

At Burnley, the civic reception committee were delighted the Battalion should visit the town on the first anniversary of Britain’s entry into the war. The enthusiasms of Chorley and Accrington were repeated as the Battalion entered the town. Several thousands watched as the Mayor welcomed them in the Market Square, the jealousies and apathy of September 1914 long forgotten. The speeches ended with the Mayor’s hope that the Battalion would enjoy itself in its evening in Burnley (free tickets to the Empire Theatre were available) and the men again were allocated billets. Once again scores of ‘we Accrington Lads’ decided to forgo that pleasure, and went again absent without leave, back home. The following day Thursday, August 5th, 1915 the Battalion reached South Camp, Ripon.

A family snap of Pte. A. S. Edwards (fourth from left) as ‘Z’ (Burnley) Company march through Accrington on the recruiting visit.

As a public relations exercise the Battalion’s visit home was a triumph. As a recruiting drive it was an abject failure. In Chorley just four joined the Battalion from a total of eleven of the Mayor’s ‘shirkers’ who enlisted that week. In Accrington, Rickman admitted results ‘had not been good’. Time and events had faded the euphoric enthusiasms of 1914. Since then the Territorial Battalions of Chorley, Blackburn and Burnley had suffered the disasters of Festubert and Gallipoli.19 Local military hospitals were overcrowded with the wounded of France and Belgium. Alarming letters from survivors of heavy fighting filled the newspapers. War-time restrictions, food shortages and higher prices were beginning to add to the problem of poverty. The shell-scandal, with Harold Baker’s involvement, affected public morale and convinced many the war was going badly wrong.

John Harwood, Mayor of Accrington and raiser of the Battalion takes the salute from Lt. Col. Rickman as the Pals march past the Town Hall.

“We dismissed on the market square, and permitted to go to our homes, a privilege much admired. On Monday we had to parade for a route march through the District, i.e. Rishton, Great Harwood and Clayton-le-Moors, but I received orders that I, along with Sgt. Kay, had to proceed to Ripon that afternoon. Three o’clock saw myself in the side-car of Sgt. Kay’s motor-bike speeding along to Ripon.”

J. Bridge

The demand for munition workers, with their high wages, for a war which was not going to end for some time, also affected recruiting. Old style recruiting marches seeking out ‘likely young men’ in a crowd watching a parade could not compete with the Munitions Work Bureau, which in Accrington during the Battalion’s recruiting visit, enrolled a hundred workers. Also those already in employment, particularly in the cotton-mills, were loth to enlist because employers in 1915 would not assure them of their jobs after the war.20 It remained also that those with good health, patriotism and a sense of adventure had already enlisted for Harwood in 1914.

Twelve months later however, Harwood’s ability and experience were still required by the war Office, as they made clear in their formal letter of thanks for raising the Battalion. The opening compliments were somewhat diminished by the broad hint of his continuing responsibility to provide recruits.21

By that time, recruiting had become a national and a political matter. In October 1915, as a last attempt to make a voluntary system work, Lord Derby introduced a scheme by which men of military age ‘attested’ their willingness to serve when called upon. The scheme failed, therefore in January 1916, Asquith introduced conscription for single men, followed in May by universal conscription. So, as recruiting was starting to lie outside the range of the Battalion’s military duties, the men settled down at Ripon.

Ripon, the ancient market town between the Vale of York and the hills and pastures of Nidderdale and Wensleydale, in 1915 became a military town, with its normal population of 7,000 swollen to 47,000. South Camp was one of several on the town’s outskirts. In contrast to Rugeley, the sun shone on the Battalion as it arrived, the huts were electrically lit, the recreation rooms, stores, stables and offices, etc., ready for use. The men looked forward to an enjoyable stay in what many believed to be the finest scenery in the North of England.22

Men were again allowed leave, and the return to military life came harder for some than others. Pte. H. Riley of Clayton-le-Moors, Ptes. Tom Winchester, Jack O’Connor and William Pye of Church, Pte. John Winter of Accrington and Pte. Thomas Iddon of Chorley, needed to be brought back under escort. In Rickman’s farewell speech in Accrington, he spoke proudly of there being only one man absent from the final Battalion parade. Pte. Iddon was that man. Whilst absent without leave, Pte. Iddon had been drunk and disorderly (damaging a policeman’s uniform) and fined 14/- ‘for a dis-graceful exhibition for a man in uniform.’ There is unfortunately no record of how he fared before his inevitable appearance before Col. Rickman.

Returning home from Burnley had its difficulties. Pte. Marshall started the journey with a group.

Members of ‘X’ (District) Company have tea at South Camp, Ripon.

“Some of the lads went for a drink when we changed trains. They missed their connection so were late back to camp. They told the Company Commander they were returning for the train when a band on the station played, ‘God Save the King’, and as they stood to attention, the train left without them! The Company Commander didn’t believe them, of course, but they got away with a reprimand.”

It became fashionable for relatives to visit the camp at weekends as Ripon lay only about three hours by train from East Lancashire. Pte. Glover’s father, from Accrington, more fortunate than most, could visit both his sons — Clarrie at Ripon, and Willie, ten miles away at Masham with the 158 (Accrington and Burnley) Howitzer Brigade in 34 Division.23 L/Cpl. Bradshaw’s father described Sunday afternoons at South Camp, “The whole area is crowded with visitors. The huts are comfortable and clean and the situation is dry and healthy.”24 Not all agreed. Pte. Marshall:- ‘Our huts were crawling with earwigs. We all slept with our cap-comforters on for protection.’

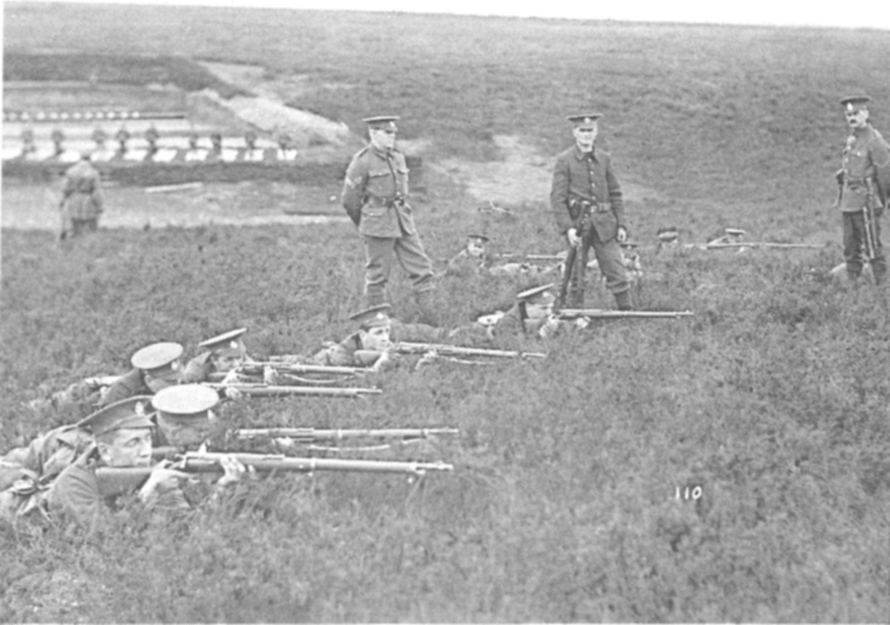

‘W’ (Accrington) Company practice aiming on the rifle range at Wormold Green.

Apart from this, most men remembered their eight weeks at Ripon with pleasure. ‘W’ and ‘X’ Companies ‘christened’ a brand new rifle range at Bishop Monkton, four miles away. They were able to relax, walking in the countryside or swimming in the River Ure, as the other Companies fired their part of the course. ‘Y’ and ‘Z’ Companies in their turn then relaxed as the other two Companies fired the next course, and so life went on for all. The complete firing course on ranges with targets at 100 yards to 600 yards took four weeks. Everyone, officers, N.C.O.’s, cooks, sanitary men, etc. became proficient to some degree. Col Rickman, who also fired, considered the course results with their high percentage of first class shots — as very satisfactory indeed. The results were remarkable as the rifles were worn-out Lee Metfords. Most men enjoyed the course for they found it individually more satisfying than trench-digging and bayonet-charging dummy ‘Gerries.’ The results were so consistently good there was more than a suspicion of a ‘fiddle’. After all, in a ‘bulls-eye’ a pencil made the same sized hole as a bullet. No one cared very much — the results were too good for morale.

Men of ‘X’ (District) Company await their turn on the rifle range. Some men are still wearing Melton blue uniforms.

“We were usually on parade by 4.30 a.m. and marched to the range, usually returning about 5.30 p.m. Rations were issued in the field; to which I did full justice, although the tea was always smoked, which I understand is quite unavoidable.”

J. Bridge

The Battalion was taking shape. The transport section became fully equipped with the delivery of forty four mules for drawing the new field kitchens and ammunition wagons. The unbroken mules were a problem from the beginning. Six hundred arrived by rail at Ripon. Men from 34 Division (also based at Ripon) unloaded them only to find they were for 31 Division. Minutes later another train load of six hundred mules arrived for 34 Division. In a station yard full of squealing, kicking mules, Lt.Bury, O.C. Battalion Transport, and his men, selected their forty four mules from the confused mass and got them back to camp. Lt. Rawcliffe watched them arrive—and leave.

Captain H. D. Riley leads his men of ‘Z’ (Burnley) Company on the march through Ripon on the way to the rifle range.

“Poor Harry Bury! Mules are fractious beasts at the best of times, but these were devils. They were no sooner in the compound, when they broke out and headed for the open countryside. They scattered in every direction, with Harry and his men after them! Some went up to four miles away. It took days to round them up again. It was hilarious for us of course —we hadn’t to catch them!”

By the Summer of 1915 the Battalion was used to inspections by the ‘top-brass’ but two at Ripon gave Rickman particular pleasure. On August 11th, Major Gen. Sir A. Murray K.C.B., D.S.O., Deputy Chief of the Imperial General Staff, told Rickman “I have inspected tens of thousands of troops in Kitchener’s Army but I have never seen a smarter, better turned out Battalion. A great deal of trouble has been taken and I am delighted.”25 Rickman, understandably, shared his pleasure in Battalion Orders, that, ‘We are some battalion.’ A few days later Major Gen. R. Wanless O’Gowan, G.O.C., 31 Division, added to the Battalion’s high opinion of itself when he told them he, as an ex-East Lancashire man (he had served with the 1st Battalion) had expected them to be smart and they had exceeded his expectations.

These compliments specially pleased Rickman. On his responsibility alone, he at forty one, a comparitively young Commanding Officer, had to bring the Battalion to active service standards. He achieved much in his six months without the help of a single officer or N.C.O. with recent battle experience, although he was not to know that the ‘active service standards’ were unrealistic for trench warfare.

Rickman’s responsibilities did not distance him from his men, his reputation for kind hearted autocracy being enhanced on the day of the G.O.C.’s inspection. Pte. Fisher was eighteen. “We had just come off parade and a telegram awaited me at the Company Office. My mother had died, I was only a lad and was in tears. The C.O. came in, very stern and formidable, and to my utter surprise, said very softly, ‘My boy, try to compose yourself.’ He then turned to the Sergeant and literally roared, ‘Take that man’s name and send him home immediately!”

After the G.O.C.’s inspection, 31 Division prepared to move to Salisbury Plain, always considered a staging post for the Front. With 94 Brigade the first to go, the Battalion immediately got one week’s home leave. Smarter, fitter, better nourished than the ‘Harwood’s Babes’ of the year before, men in their hundreds visited the photographic studios of East Lancashire, some alone, some with friends, some with wife and children for the final ‘keepsake to remember me by.’ An air of finality spread — this was ‘it’ — the ‘Pals’ were going to the Front. In an effort to supply the Battalion with appropriate material, a thousand sand-bags were hurriedly made by the officer’s wives or girlfriends of the Pals Comforts Committee. “The process of daubing the sand-bags with irregular patches of green and brown, said to render them invisible to the enemy, was not undertaken by the ladies, however.”26

By a sad coincidence, as Accrington streets were crowded with men on leave, two of the reserve company died from illness.27 As leaves ended there came sadness also to many homes. This time no cheering thousands ‘saw the Pals off as they caught the special trains to Ripon. The crowds round the station approach were subdued and tearful as families and friends bade their farewells. Many were convinced that their men were bound for Gallipoli to share the fate of the Territorials.

On Friday evening, September 24th, the Battalion left Ripon for Hurdcott Camp, Salisbury Plain. After an uncomfortable twelve hour train journey, via Sheffield, Leicester (tea served at 3 a.m.) and Cheltenham, they reached Wilton at 8.30 a.m. A five mile march in pouring rain on roads ankle deep in mud brought them to yet another new hutted camp — Rugeley all over again, with Ripon but a dream. The camp stood unfinished, with no lights, no tables to dine on, no cookhouse, the ground a quagmire — and bloody miles from anywhere.’

Hurdcott Camp lay on the southern edge of Salisbury Plain, seven miles from the Cathedral city of Salisbury. The nearby villages of Bur-ford St. Martin, Fovant and the town of Wilton had few recreational facilities. In the event, the men had little free time to visit these places as the Battalion entered its busiest phase so far. Almost at once brand new Short Magazine Lee-Enfield rifles and Lewis light machine guns were issued. Equipment for signallers, bombers and medical staff appeared. It became clear the previous slow pace of life caused by lack of materials and equipment was to be made up by intensive training. Now that almost all equip-ment had arrived the military organisation and structure of the Battalion was complete.

Pte. Sayer of ‘Z’ Company, now one of 16 bombers in the Company, described a typical day at Hurdcott for the specialists.

“Early morning cup of tea and a biscuit was followed by physical training in loose dress. After a good breakfast 9 o’clock ‘fall in,’ had everyone on parade. Col Rickman was a stickler for discipline and transgressors were ‘for it.’ Specialists marched off to their own jobs and the Bandsmen became stretcher-bearers. The Sanitary Squad enjoyed their buckets and spades. The Water-Cart team — what they did nobody really knew and were best left alone with their tanks of water and tins of chloride of lime. The Lewis-gunners and signallers were rather high-brow — they were ‘brain-workers’ and dignity was the acquisition. In contrast were we burly Bombers, housed in two separate huts, whether for our own welfare or the peace of mind of the rest is not known. The Police under ‘Ow’d Nick’ were near the general factotums, the Pioneers. Hidden away in nooks and crannies were the Officers servants, Mess waiters, Grooms, Cobblers, Tailors, Orderly Room staff and sometimes Detention men and Prisoners. Dinner was usually a big meal, then training until tea at five. Then the evening off unless there were manoeuvres or guard duty.”

“We started on our march to camp wondering what sort of a place we were going to now. It was a weary march after travelling all night. The mud was ankle deep but we arrived about noon quite ready for a good feed. The camp was a new one and therefore very clean. ”

J. Bridge

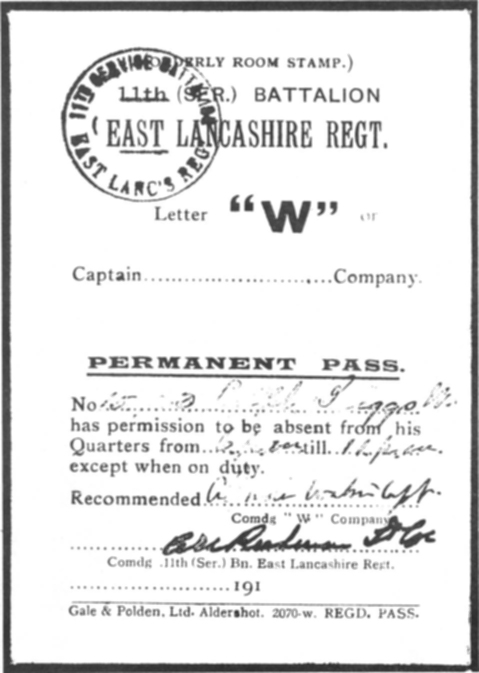

L/Cpl. Brigg’s permanent pass.

A wounded veteran of the front pays a visit to friends in the Blackburn Detachment at Hurdcott Camp.

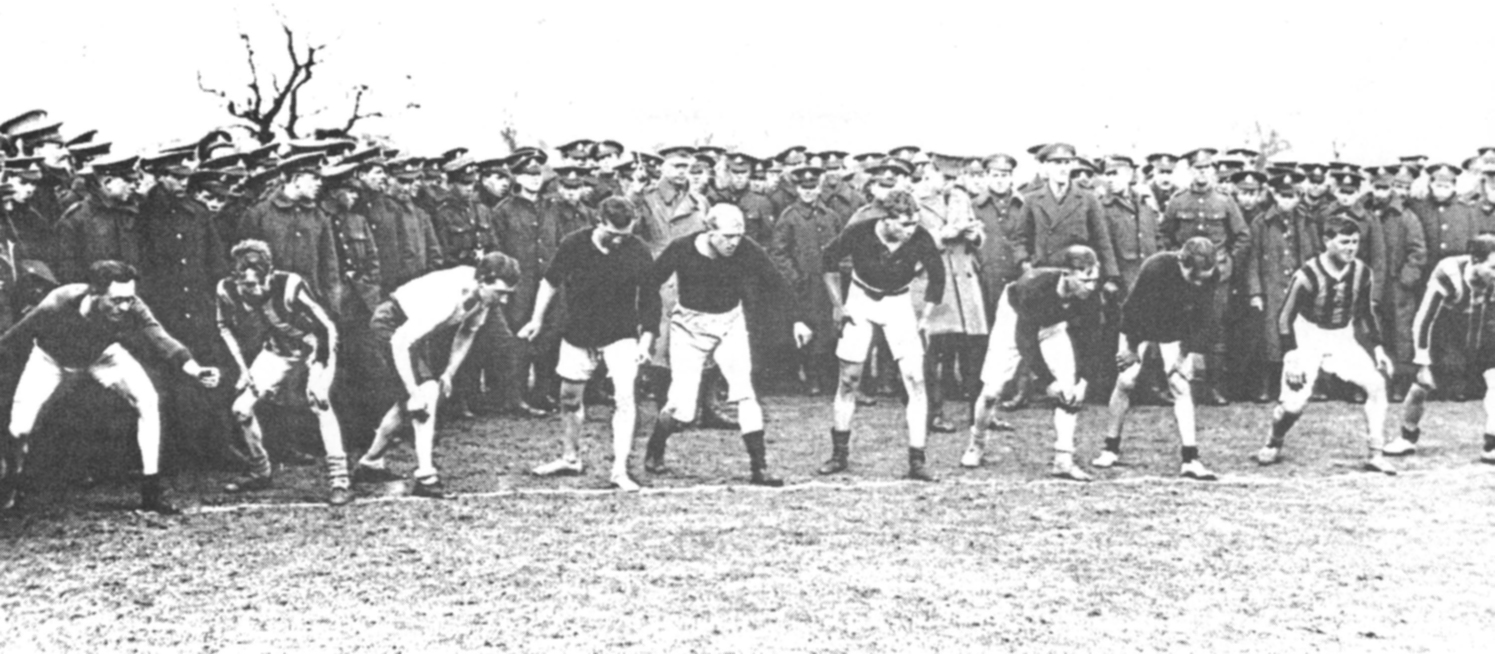

31 Division Sports Day on October 21st, 1915. Here the ‘Pals’ cross-country run team, mostly Burnley Lad’s Club members, line up for the start.

Although the Battalion Concert Party and Glee Club entertained in the Y.M.C.A., and the Regimental Band gave regular concerts, inter-Battalion and inter-Brigade sporting rivalries were still encouraged. The tempo of training contrasted greatly with anything before. Manoeuvres and field exercises came before all else as 31 Division made its final preparations for active service in the last four months of 1915.

New, tough, instructors fresh from the trenches of France appeared and training became more relevant to battle conditions. Crowded days were spent digging trenches and laying barbed wire. The bombers practised clearing ‘enemy’ trenches with the new Mills bomb. Lewis gunners learned just how many different ways a Lewis gun could jam in action (reputed to be twenty seven). Battalion, Brigade and Divisional manoeuvres tested the organisational skills of transport, cook-house and signal sections. Ten days training at Hurdcott contrasted completely with the same period at Rugeley (see Appendix 2 (b)). ‘Bloody miles from anywhere’ or not, after a strenuous day in the field Hurdcott felt like home to everyone.

A card posted to Miss Ada Woods from ‘Will’ (surname unknown) November 1915.

“Well, this place was about the limit. Inches deep in mud the hutments were filthy, the blankets similar and rats, mice etc., abounded. I took all my belongings and my bed into the Orderly Room, which I might add was the warmest place in the whole camp, so during my stay I made myself very comfortable.”

J. Bridge

Thoughts of home entered the minds of many with the realisation that their time in England was limited. Many had saved up the money, or wired for it from home, to have a final forty eight hours leave. Others, Lt. Rawcliffe in Accrington and L/Cpl. Race in Burnley amongst them, got extended leaves to get married. Lt. Rawcliffe returned to find that there had been a ‘to do.’

“Jack Ruttle and George Williams (both Lieutenants) had decided to shave off their moustaches. On morning parade Col. Rickman saw them. ‘You’ve shaved off your moustaches’, he roared, ‘Yes, Sir’, ‘Get off my parade and don’t come back until they’ve grown again!’ The lads were in a real dilemma. How on earth could they stay off parade for days on end? Old Rickman soon relented, of course, his bark was always worse than his bite.”

By now the October ‘Indian Summer’ changed to a wintry November. Days of heavy rain alternated with severe frosts. Mettle was tested as nights with temperatures as low as minus ten degrees of frost were experienced. Letters home pleaded for tins of cocoa and OXO cubes to be sent — quickly. Other nights were spent in trenches deep in ‘slutch’ (mud) as rain poured on ‘defender’ and ‘attacker’ alike. On bright, clear nights young officers tested newly acquired skills in astronomy by setting courses for route-marches by the stars — luckily, always successfully.

On November 16th, the Battalion marched fifteen miles to Larkhill Camp, in the centre of Salisbury Plain, to take their final firing course. At Larkhill, no preparations for their arrival had been made — no food, no bedding, no coke for the stoves. The Battalion seemed fated to arrive at places unprepared to receive them. Chaos reigned for five hours — from 2 p.m. to 7 p.m. — until all were settled in. L/Cpl. Bradshaw wrote “God only knows how we would have gone on but for Col. Rickman. At 7 p.m. he had not taken his full pack off. He was everywhere. He is ‘some’ Colonel.”29

When finally underway, the firing course turned out to be even more enjoyable than that at Ripon. Everyone felt infinitely more satisfied to fire his own personal rifle, the rifle he had to take and use on active service. The Lewis gunners, though, did not share the same sort of feeling towards their light machine-guns, but they also passed their proficiency tests and for-med into permanent teams.30 After sixteen days the Battalion returned to Hurdcott Camp with a feeling of readiness for the Front and a great anxiety to be there.31

More new equipment arrived, but to the men’s disappointment the new haversacks, valises and straps were the “old fashioned’ leather, rather than the canvas webbing more generally in use. For the Lewis gunners of ‘W’ and ‘X’ Companies, ‘the best machine-gunners in the Brigade,’ came eight pairs of binoculars bought with £10 raised by an auction of jewellery by officers’ wives in Accrington.

Officers were posted in — and out. Major E. L. Reiss, on active service in France since November 1914, reported as Second in Command. Amongst a batch of new subalterns came 2/Lt. Wilfred Kohn, son of a family friend of Rickman, whom Rickman had promised to “take under his wing.’ 2/Lt. Rigby of ‘Y’ Company was the senior of several men who volunteered for transfer to the newly formed Machine Gun Corps. A final batch of men were transferred to munitions work.

Company Commanders combed out their unfit and less than soldierly members for transfer to Prees Heath. A replacement draft of twenty four men from Prees Heath arrived in late November. A delighted Pte. Snailham came with them.

“I saw on Company orders the Battalion required men, so I appealed to my Company Commander to be allowed to go. He knew I was seventeen but he granted my appeal. I came, not to my own Chorley Company, but to ‘Z’, Burnley Company, but I didn’t mind, I was glad to be back.”

On Monday, November 29th, 31 Division received orders to move to France on Tuesday, December 7th. The waiting was over! At once a frantic rush for forty-eight hour passes arose, with Accrington Post Office inundated with telegrams asking for money for the fare home. Many ‘straining at the leash’ to get to France suddenly felt a desire for the ‘great day’ to be delayed for just a week, the better to say goodbye to those at home.

Pte. Glover, as one of the Battalion advance party, had no such opportunities. The advance party were informed at 11 p.m. on Monday of their departure for Le Havre at 6.30 a.m. on Tuesday. While they were there, however, the order for the Division to move was cancelled. The day after, Pte. Glover with family souvenirs of Le Havre and a sense of anti-climax, returned with a disconsolate advance party to Hurdcott Camp.

While the advance party were away Pte. Snail-ham was very busy.

“They suddenly realised our draft hadn’t Gred the musketry course, so we were rushed off to Larkhill. We knew we had to pass to go on active service. We fired our course in the most dreadful wind and rain imaginable. It was a farce. We couldn’t see the targets, let alone hit them. By a miracle — or a fiddle — we all passed with good marks!”

With the recall of the advance party, rumours abounded about the Battalions future destination. These were partly answered by the issue of solar topees and puggarees — it was to be the East, but no one knew where or when. The ‘when’ came sooner than expected. With embarkation leave arranged and a special train for East Lancashire steaming up ready in Wilton station, a Divisional Order arrived for the recall of officers, N.C.O.’s and men already on leave and all future leave cancelled. Bad as this was, at least the Battalion escaped the fate of the 12th, 13th and 14th York and Lancaster Regiment who were almost in Sheffield when their trains were stopped, engines coupled to the rear, and the trains brought back.

Another card to Ada from ‘Will’. “Dear Ada, just a line hoping you and all at home are well. Dear Ada I did not know they would alter our leave. I will try to come on Thursday if I can get off.”

Following this disappointment the Battalion had a final inspection by Brig. Gen. G. T. C. Carter-Campbell, O. C. 94 Brigade. For the second time in four months, Rickman said how proud he was of his men and from the whole Battalion only one man was absent. (Meanwhile at Church Magistrates Court, Pte. Thomas Grundy, absent since November 28th, was remanded for escort back to camp, — and, no doubt, an interview with Rickman.)32

On December 2nd, 31 Division received orders to embark for Egypt on December 6th. 94 Brigade to embark between December 18th and 28th. With this news, the men, confined to camp for the past week, were allowed out for short intervals. Those with relatives in the ‘Howitzers’ went to Bulford, others went sight-seeing in Salisbury. This leisure time ended on December 10th, when the Battalion rehearsed its move from camp. Each man was heavily laden, with all his possessions, in Field Service Marching Order complete with solar topee. The transport section, with mobile stores, kitchens, etc. accompanied them. The march ended in disaster, because all maps of the district had been handed in, consequently the Battalion lost its way. An intended three miles march became ten miles. In pouring rain the roads became churned into ankle-deep mud and when at last they returned to camp the men were completely exhausted.33

Three Burnley ‘mashers’ names unknown, at Hurdcott Camp.

The Battalion leave camp on the rehearsal march on December 10th, 1915. Leading are the Pioneer Section carrying axes.

N.W. Film Archives

As embarkation time approached a busy Rickman found time to ensure the different Comforts Funds of Accrington, Burnley and Chorley were spent wisely and fairly. For some reason the Accrington fund lagged far behind those of Burnley and Chorley (each of which had almost £300 in the kitty). Reminding Harwood of this, Rickman optimistically wrote, “As soon as I know what they (the men) are likely to require I will let you know. I think it is better than having things sent which are not wanted.” 34 The men decided on tobacco, cigarettes and writing-paper but in the event Rickman ordered that these would come only after Battalion specialist equipment needs.

The Battalion hourly expected to receive its detailed orders to move. At last on Wednesday, December 15th, orders came to embark on Sunday, December 19th. At once, a flood of fare-well postcards, letters and telegrams went to hundreds of homes. To Harwood from Rickman, a letter:- “Just a short line to tell you we embark on Sunday. The men are well and in good spirits. Thank you for all you have done. Goodbye and Good Luck.” Harwood wired in reply, “To Lt. Col. Rickman, officers, N.C.O.’s and men, wishing you God Speed, Good Health and a safe return.” 35 To the Mayor of Chorley from Major Milton, a telegram:- “Chorley Pals wish you and all the inhabitants of Chorley farewell and prosperity.”36

Postcard from Pte. A. T. Lomax. “Dear Mother, I am glad you are all well. If father is in Liverpool on Monday or Tuesday he might see some of our Division leaving there. Their colours are red and white chevron just below the collar on the back and are wearing sun-helmets. We expect to leave on Thursday but don’t know where we will sail from.” Abel.

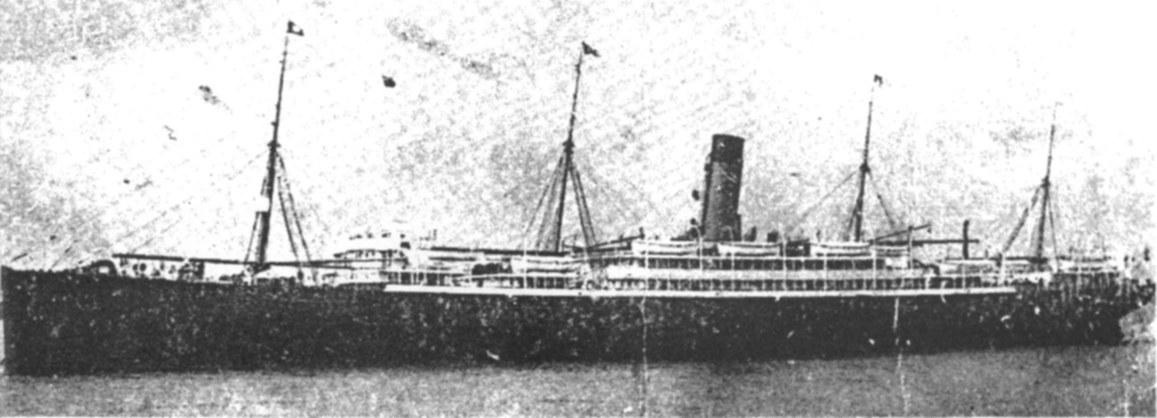

Farewells made, the final march of the Battalion in England took place in the quiet, early Sunday morning hours along the empty roads and sleeping streets of Wilton and Salisbury. There were no cheering crowds, no songs to bring blushes to the cheeks of young ladies, as they silently entrained at Salisbury station for Plymouth and Devonport. At Devonport, Company by Company, the Battalion boarded the T.S.S. ‘Ionic.’ The Battalion War Diary recorded the figures. “Twenty nine officers, including one R.A.M.C. and one Roman Catholic Chaplain, plus 956 O.R.’s.” (Two officers and forty seven O.R.’s [the transport section] boarded the T.S.S. ‘Huanchaco’ at Plymouth).37

As the men awaited the ‘Ionics’ departure they bought hundreds of postcards of the ship for a final brief message home. Pte. Cocker of Accrington wrote. “Dear Wife and child, Goodbye until I return. We set sail today, Sunday.” Pte. Cocker, with all the other writers, was not to know that the postcards were taken along on voyage and not sent home until passed by the censor, Lt. H. Ashworth in Pte. Cocker’s case — this was on January 16th, 1916. The carefree days of ‘Camp Correspondent’ were now replaced by the exigencies of censorship, although pictorial views of Egypt were soon to arrive at many homes in East Lancashire.

At 5 p.m. the ‘Ionic’ moved off to The Sound to await its escort of destroyers. As the band of the quayside farewell party played ‘Auld Lang Syne,’ Rickman’s thoughts could only be guessed at as he viewed the end of one phase in his — and the Battalion’s — life, and the beginnings of another. He was a soldier too experienced to be afraid for himself, but certainly he must have felt afraid for the future of his men. Few had little idea of what lay ahead, simply to go abroad being adventure enough. A letter to Harwood expressed his thoughts, “You have given me a big charge in the men’s lives. I only hope I shall be able to help them in the life that’s before them.”38

After the lonely and exacting task of producing a Battalion the equal of any in Kitcheners’ Army although admittedly not perfect — (not many Battalions could get lost on a three mile route march) Rickman had the more exacting task of leading his Battalion through its longed-for active service.

The 12th Reserve Battalion was left behind at Prees Heath Camp, Shropshire. With them were Lt. T. Y. Harwood (grandson of John Harwood), back, 2/Lt. Goodall, left, and 2/Lt. Standring, right.

The 12,232 ton White Star Liner T.S.S. ‘Ionic’, a sister ship of the ill-fated ‘Titanic’.

1. Described also as ‘Cannock Chase’, Tenkridge’, Tenkridge Bank’, confusion exists about the actual name of the camp. Both ‘Rugeley Camp’ and Tenkridge Bank Camp’ postmarks were in official use during the war. (See Great War Camps on Cannock Chase, C. J. Whitehouse and G. P. Ibbotson).

2. History of ‘Z’ Company Page 8.

3. The Army School of Cookery, which had been gradually raising the standard of cooking in the ‘old’ Army, unforunately disbanded at the beginning of the war. However, schools of instruction in the home Commands and close supervision of the Quar-termasters-General quickly improved the quality of the meals and supplies of food were mostly adequate. (The ‘Z’ Company protest was an isolated, domestic affair).

4. The ‘Comic Band’ of an Accrington engineering works played in carnivals, charity parades, etc. Its instruments were washboards, bin-lids, tin whistles, etc. The Tals Comic Band’ subsequently played in many Battalion concerts raising money for Accrington charities. An unofficial ‘duty’ was to play ‘Home Sweet Home’ and similar ditties, as batches of men went on leave thereafter.

5. A.G. 5/6/15

N.B. At Rugeley Camp, L/Cpl. Russell Bradshaw, the son of an Accrington draper and close friend of John Harwood, became ‘Camp Correspondent’ for the Accrington Gazette. He kept his unofficial post, in spite of later censorship, for over three years. In a letter to the author in November 1983. Mr. Bradshaw said, “It’s a wonder I didn’t get shot for some of the news I sent!”

6. In May 1915, ‘S’ Company became, at Chadderton Camp, Depot Company of the Battalion. The 11th Battalion, therefore, alone in the East Lancashire Regiment, had the privilege of its own Depot. The War Office request increased its establishment to two Companies and they became the 12th (Reserve) Battalion. In October 1915 the 12th Battalion moved to Prees Heath Camp and in September 1916 became 75th Training Reserve Battalion, 17th Reserve Brigade.

7. Pte. Coady wrote a poignant farewell letter to his friend Isaac Edwards in Caernarvon. For some reason it appeared in the Accrington Observer and Times on June 12th, 1915, ‘Dear Mr. Edwards, It looks as if we will be in France before long. I do not care how soon, I joined the Army to fight Germany and I am pleased I did so. When I go into battle I know the game because I am in the hands of God and whatever will be my fate I won’t grumble. If I get killed I hope to go where there are no battles. — Yours Tom Coady.’

8. It is highly probable the group included the several businessmen, magistrates and civic leaders whose sons were serving in the Battalion.

9. Mr. J. Whitworth, former conductor of the 4th Loyal North Lancs (Territorial) Band and the North Lancs (Chorley) Band. From September 1914 to February 1915 the latter band led the Chorley Company on their civil marches and church parades. Several former bandsmen were serving in ‘Y’, (Chorley) Company.

10. A History of the Accrington Pals Page 72.

11. As early as January 1915, Lloyd George, in a memorandum for the War Council of the Cabinet, described the Kitchener Army — “In intelligence, education and character it is vastly superior to any army ever raised in this country”. (See Lloyd George: Twelve Essays, Ed. A. J. P. Taylor Page 99).

12. Many in Chorley Company lost friends and relatives at Festubert. The l/4th Loyal North Lanes (Territorials) lost 10 officers and 250 men, killed, wounded or missing.

13. H. Baker, Accrington’s M.P. was one held responsible for the shortage of shells and was replaced, on June 19th, as Financial Secretary of the Army Council by Mr. H. W. Forster, M.P. He was, however, immediately, in the June King’s Birthday Honours list, appointed a Privy Councillor.

14. The Bulk Release Scheme consisted of a call by the Ministry of Munitions to all skilled men within ‘non-barred’ units, i.e. units which had not undergone advanced training or did not require skilled men. (See ‘Arms and the Wizard’, R.T.Q. Adams Page 96).

15. One recruit was Arthur Riley. A single man, he returned from Pawtucket, Rhode Island, U.S.A. in 1915 to his parents’ home in Accrington to enlist. He was the town of Accrington’s first fatal casualty in France when he died of wounds, April 30th, 1916.

16. Pte. Bell, an ex-reservist, by coincidence, served with Col. Rickman in the South African War. He was killed in action on July 1st, 1916.

17. C.W.N. 31/7/15.

18. History of ‘Z’ Company Page 9.

19. The 1/4th and 1/5th East Lancs Territorials had suffered severe losses in Gallipoli since May 1915. In late August, Burnley received news of the loss of thirty six men of the 2/2nd East Lanes Field Ambulance on the troopship ‘Royal Edward’ sunk in the Mediterranean with the loss of 861 lives.

20. Put as a reason when not one man responded to a recruiting appeal for the reserve company in Oldham (admittedly not a traditional East Lancashire Regiment recruiting area) in September 1915. (See Oldham Chronicle, 4/10/15).

21. War Office, London 18/7/16. Sir, I am commanded by the Army Council to offer you — their sincere thanks for having raised the 11th Service Battalion East Lancashire Regiment (Accrington) of which the administration has now been taken over by the military authorities. The Council much appreciate the spirit which prompted your assistance and they are gratified at the successful results — which added to the Armed Forces of the Crown, the services of such a fine body of men. — I am to add that its (the Battalion) success on active service will largely depend on your efforts to keep the depot companies up to establishment. — I am, etc. B. B. Cubitt, Secretary. (A.G. 21/7/15).

22. By the end of the month the whole of 31 Division assembled at Ripon: i.e.

| 92 Brigade: | 10th, 11th, 12th and 13th East Yorkshire Regiment; |

| 93 Brigade: | 15th, 16th, 18th West Yorkshire Regiment and 18th Durham Light Infantry |

| 94 Brigade: | 11th East Lanes Regiment. |

| 12th, 13th and 14th York and Lancaster Regiment. |

In addition were Artillery brigades, Engineering and Transport Companies, Pioneers, etc. (See Order of Battle of Divisions, Part 3B, History of the Great War, H.M.S.O. London 1945).

23. On January 14th, 1915 the War Office requested John Harwood to raise a Howitzer Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, in East Lancashire. Recruitment ended after four weeks.

24. A.G. 11/9/15.

25. B.E. 14/8/15.

26. A.O. 21/9.15.

27. Pte. Sam Ollerton, aged 20, a single man, died at his home in Accrington and buried in Accrington Cemetery.

Pte. Fred Hacking, aged 22, a single man, died at his home in Oswaldtwistle and buried at Immanuel Church.

28. A.G. 20/11/15.

29. There were sixteen Lewis gun teams, four per Company. Pte. Pollard completed his course and became No. 6 in his team. The rest of the team were:- Cpl. Sam Smith, Ptes. Harry Kay, Tom Carey, Walt Greaves and Harry Wilkinson, all from Accrington.

30. Only four days were spent firing, the rest spent on ‘butt duty’ for other Battalions in the Brigade. Many men used their free time to visit relatives and friends in 158 (Accrington and Burnley) Howitzer Brigade, R.F.A. coincidentally, from September 1st, at Bulford, two miles away.

31. Northern Daily Telegraph 4/12/15.

Other plans went awry. At the same court Thomas Duckworth of Clayton-le-Moors, fined 6/- for having a fox terrier dog without a licence, told the court his son, Pte. Thomas Duckworth, asked him to keep the dog as a mascot for the Battalion. Pte. Duckworth, of course, was unable to collect.

32. On hearing the news of the impending embarkation, Harwood arranged for a cine-photographer to film the Battalions’ departure for showing in local cinemas. The cameraman however, filmed the men leaving camp on the rehearsal march. It is fortunate he did not film the return.

33. A.G. 11/12/15.

34. A.G. 25/12/15.

36. C.G. 25/12/15.

37. 11th East Lanes Regimental War Diary, December 19th, 1915. The War Diary, started December 18th, 1915 continued until March 3rd, 1919.

38. A.G. 11/12.15.