Chapter Five

An eastern interlude

By the autumn of 1915, the British High Command recognised that the Dardanelles campaign had failed. After the landings at Anzac Cove and Cape Helles on April 25th, the assault against the Turks turned into one of the most arduous and costly operations of the war. What-ever advantage had been gained by a landing at Suvla Bay on August 6th had been lost by the second day and the enemy lines remained as impregnable as ever.

On October 11th, 1915, Kitchener asked the Commander of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force for estimates of the losses which might accompany a withdrawal from the Dardanelles. The Commander, Gen. Sir Ian Hamilton believed such a step ‘unthinkable.’ Four days later, on his recall to London, Kitchener informed him a fresh unbiased opinion from a ‘responsible’ commander was desired.1 Hamilton’s successor, Lt. Gen. Sir Charles Monro subsequently reported the British forces could be held down indefinitely. The lines had no depth, Turkish fire impeded all communications and approaches from the sea and deployment of fresh troops for offensive operations could not be concealed from enemy observation. Even a break-through would yield little military advantage, for an advance up the Gallipoli peninsula to Constantinople was now out of the question. Monro therefore advised that troops ‘locked up’ on the peninsula be given more useful work elsewhere. Such a withdrawal presented tricky strategic and political problems.

Both Monro and Lt. Gen. Sir John Maxwell, Commander of the Force in Egypt, considered withdrawal from Gallipoli would have grave effects unless Britain struck hard at Turkey elsewhere. One consideration was to use more troops for a landing at the Gulf of Iskenderun, near Alexandretta, now Iskenderun, on Turkey’s border with Syria. The purpose being to cut and hold the Turkish railway to Palestine and Mesopotamia. Another consideration was for the Allied armies in Mesopotamia and Macedonia (Salonika) to be reinforced.

As the withdrawal would give Moslem Turkey tremendous prestige with Moslems and Arabs in the near East, Egypt, with her vital Suez Canal, and now restless under a British protectorate, became a grave concern. The loss of the Suez Canal would be a disaster almost comparable with the loss of the Armies of the Western Front, so defence of the Suez Canal was an absolute necessity.

In Palestine, Turkish troops were massing, railways and water supplies were being extended and aerodromes built. In the minds of British generals came a vision of Turkish troops, fresh from their ‘Victory’ at Gallipoli sweeping through the Sinai Desert to the banks of the Suez Canal. With this, and the proposed landing at Alexandretta in mind, a further eight divisions were necessary to continue the British campaigns in the Near East. Two for the Alexandretta landing, four for Salonika and two — 31 Division and 46 Division — for the defence of Egypt. By November 19th, 1915, however, the Prime Minister and the War Committee decided against the Alexandretta landing and for an alternative, stronger defence of Egypt and the Suez Canal.

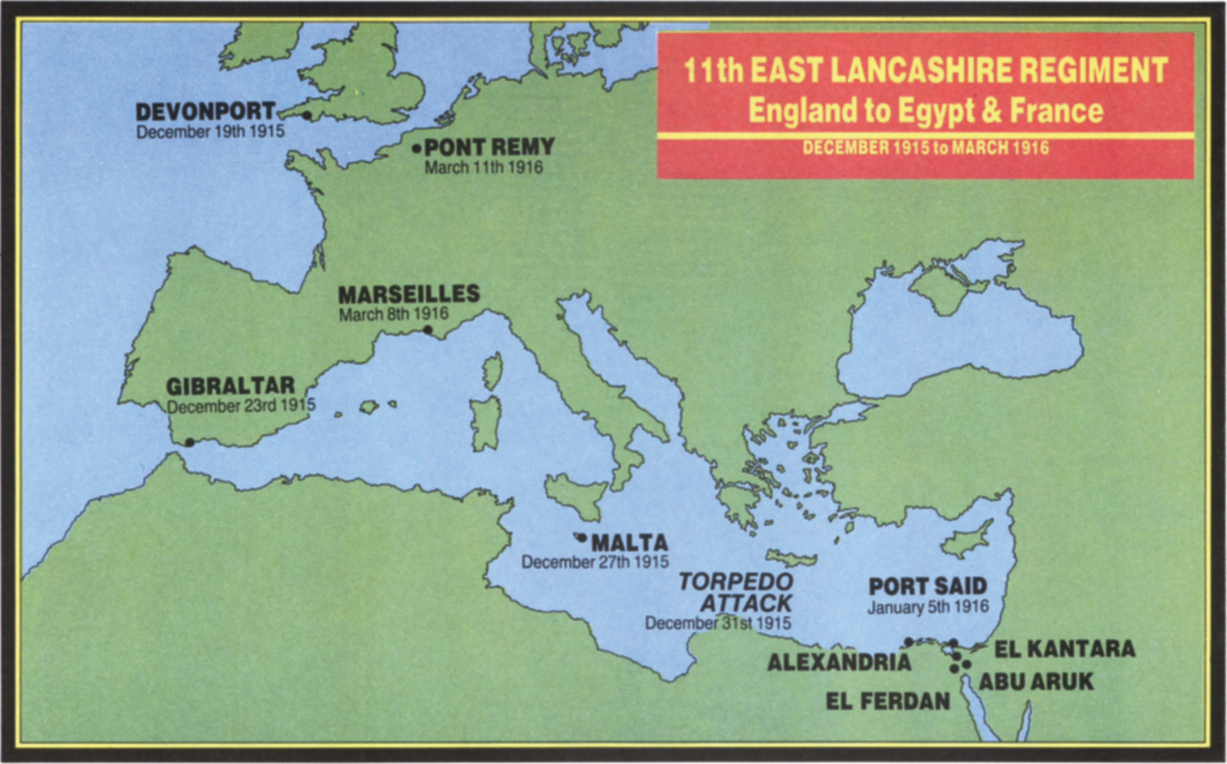

On the night of December 18th, 1915, as the 11th East Lancs were marching silently from Hurdcott Camp in England, the last of the British and Anzac troops embarked, as silently, from Suvla Bay and Anzac Cove. On January 8th, 1916, British troops successfully evacuated Cape Hellas, leaving Gallipoli and the Dardanelles in control of the Turks.

As 1915 ended the War Committee re-formed the troops freed from the Alexandretta operation and from Gallipoli, together with 31 and 46 Divisions already en-route, into an Imperial Strategic Reserve to be based in Egypt under the command of Lt. Gen. Sir A. Murray. The War Committee had decided that France was to be the main theatre of war and Gen. Sir W. Robertson, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, told Murray that as the situation in the East became clearer, no more troops would remain there than absolutely necessary. “You should therefore be prepared to detach troops from Egypt, when and if the situation makes this advisable.”2

Lt. Gen. Sir Charles Munro

Lt. Gen. Sir John Maxwell

A Turkish shell exploding on ‘V’ Beach near the ship ‘River Clyde’ during the evacuation of Gallipoli.

Barnsley Chronicle Picture Library

Meanwhile, the men of the 11th East Lancs Regiment, not knowing, nor caring much about war strategy and the role of 31 Division, were enjoying their sea voyage. Rumours about their destination were rife. Was it to be Mesopotamia, Salonika, or — heaven forbid — garrison duty in India? Most, however, were convinced they were bound for Gallipoli. After all, men reasoned, the East Lancs. Territorials were there, ‘they’ (the High Command) were bound to put the ‘Pals’ with them.

A stormy passage through the Bay of Biscay brought the Ionic to Gibralter on December 23rd for further orders and to collect two destroyers as escorts. On the way to Malta, Christmas Day celebrations started with a dinner of stewed mutton, potatoes and peas, served in Army tradition by the officers. The choice of afters limited to a bottle of beer or sixpence. Songs and recitations by the Concert Party and a selection of seasonal music by the Regimental Band followed dinner. Two days later, the Ionic, with her escort, sailed into Grand Harbour, Malta for a two day stay.

Malta, a view of Grand Harbour from the Saluting Battery looking towards Isola Point and French Creek.

Barneley Chronicle Picture Library.

Only officers were allowed ashore. Disgruntled at the freedom allowed the officers, scores of men clambered down ropes and hawsers into Maltese bumboats and bribed their way ashore. The bars and nightspots of Strait Street (the famous, or infamous ‘Gut’) were the main attraction for most. A few, such as Pte. Cowell, went further afield sight-seeing and buying postcards and souvenirs. Lt. Rawcliffe and some of his fellow-officers legitimately visited the Opera House, “where we suffered the indignity of being asked to leave for being too noisy!” Corporal Walter Todd, of ‘W’ Company, went ashore to Hospital and remained there when the Ionic sailed. There then began for him a desperate struggle with the military authorities to allow him to rejoin the Battalion.3

For some reason the Ionic sailed the most dangerous part of her journey, through the eastern Mediterranean, without her escort. All men wore life-belts continuously and there were constant boat drills. Just a few hours out of Malta, Pte. James Wixted, of ‘X’ Company died of Siriais (heat exhaustion) and was buried at sea with full military honours on December 30th, the first battalion member to die on active service.4

The following morning, with the Ionic SSE of Crete, an enemy submarine suddenly appeared five hundred yards away on the port side. As lookouts gave the alarm and klaxons sounded, the ship quickly turned, leaving a torpedo to pass a hundred feet astern. According to the War Diary for December 31st, 1915, “all troops were at boat stations in three minutes,” and the Ionic charged full steam ahead to safety. Pte. Marshall, sitting on a spar watching a boxing competition, saw the wake of the torpedo travelling towards the ship.

“After the ship swung round we (part of ‘Z’ Company) were ordered to line the starboard side of the ship and told, ‘If you see a torpedo or a periscope — fire at it!’ Of course, we all grumbled, ‘How the heck can we damage a torpedo or a periscope with a rifle bullet!’ Nevertheless two hours passed before we stood down”.

Pte. Pollard missed everything.

“I was in my hammock reading when the hooter went for boat-drill — or so I thought (My section of fifteen men shared a raft, to be thrown overboard, if necessary, with us to follow. Trouble was, I couldn’t swim). I rushed up the stairway but took a wrong turn and found myself on the wrong deck. By the time I got to my boat-station the rest of the section were waiting. Lt. Ashworth my platoon commander said, ‘As usual, last! Get your boots and socks off! ‘I said, ‘What for?’ ‘You’ll know soon enough, you’ll be in the bloody water!” We stood there, our boots hung around our necks, for over an hour before ‘stand down’.”5

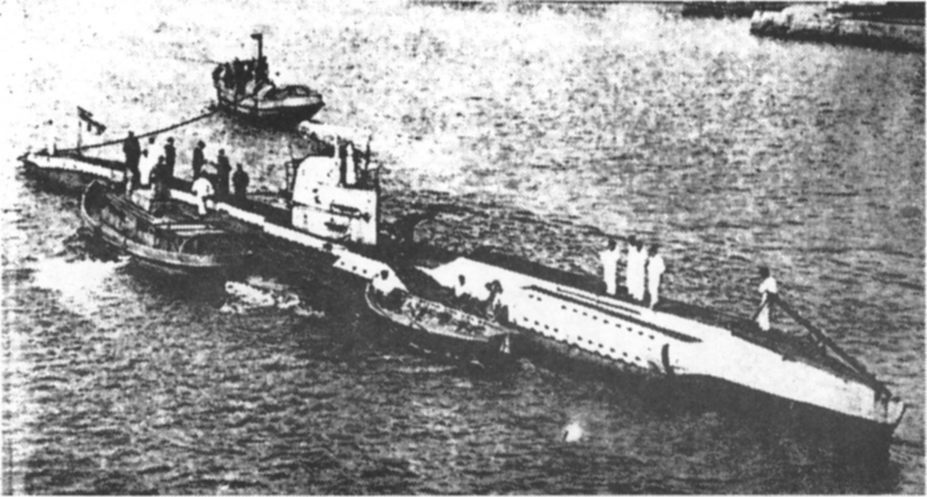

A German U-boat of the U38 class. By coincidence the U38 was launched at Kiel on September 9th, 1914, the same day John Harwood and his colleagues at Chester gained formal War Office directions for forming the Pals Battalion.

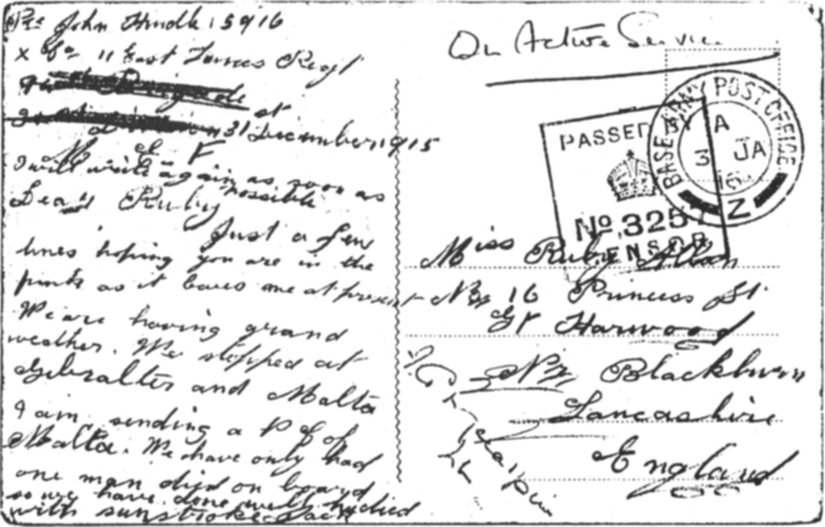

Postcard from Pte. John Hindle posted on arrival in Egypt. Censored by Lt. A. G. MacAlpine.

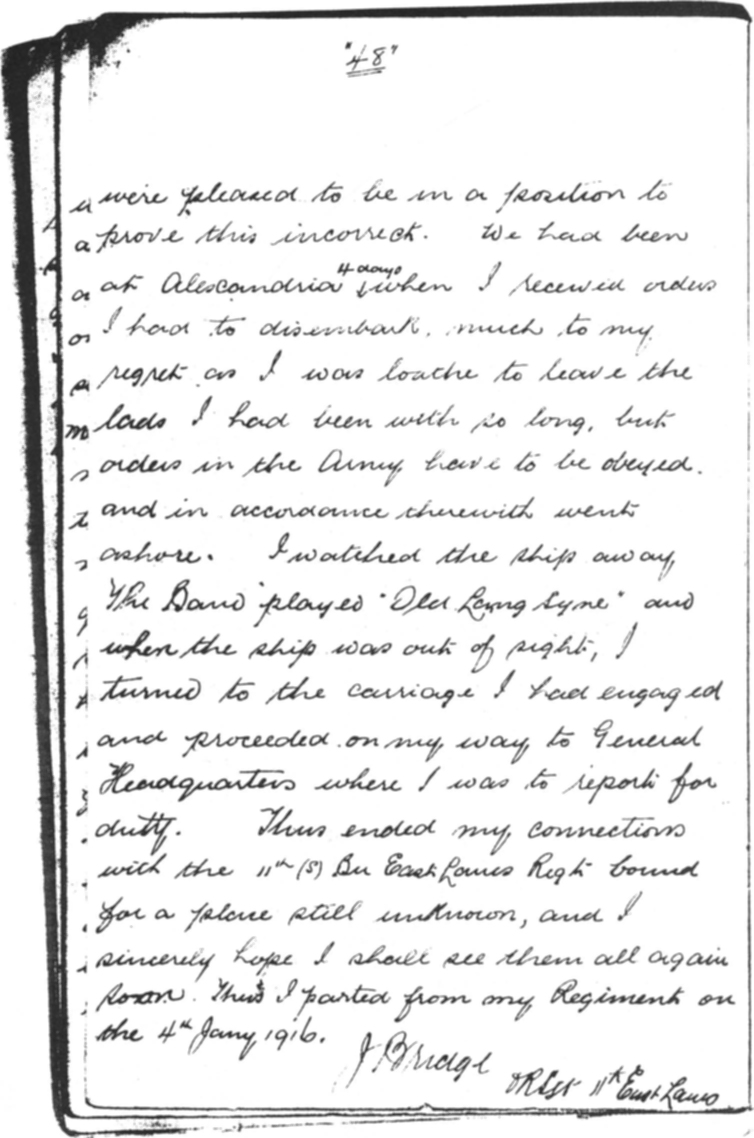

Twenty-four hours later the Ionic passed the Ras-el-Tin lighthouse to enter Alexandria harbour. While the ship lay at anchor the men watched, with a host of mixed feelings the arrival of the survivors of the S.S. Persia, which had been sunk in the area of Ionic’s escape, very probably by the same submarine. The Persia had gone down in five minutes, with the loss of 334 lives. The men also watched, with some alarm, some of the Ionic’s ballast cargo of high explosive shells being unloaded.

With a celebration of their escape in mind, many more men decided to have a night out in Alexandria, officers or no. Against explicit orders, over a hundred men made a concerted rush down the gang plank, brushed the guards aside and headed for the town. This time the indulgencies over a few men in Malta could not be repeated and a furious Rickman ordered the arrest and confinement to ship’s quarters of all involved. There is no record of any further punishment, but it is clear this was the first, and only time, any significant group tarnished the good relationship Rickman had with his men.

“A parade was called at 6 a.m. for his burial. The ships engines stopped thus everything being perfectly quiet, the ship’s bell rang once and Pte. Wixted was placed in the sea. I never saw anything so sorrowful.”

J. Bridge

Pte. James Wixted

“Here our berth had been filled as they presumed we had been sunk, as a matter of fact a cable had been despatched to the White Star Line to this effect, but we were pleased to be in a position to prove this incorrect”

J. Bridge

After four days the Ionic continued her journey to Port Said where the Battalion disembarked on January 5th, 1916. By nightfall all were encamped under canvas near the Railway Station, together with the rest of 94 Brigade. All rumours faded away, they had arrived.

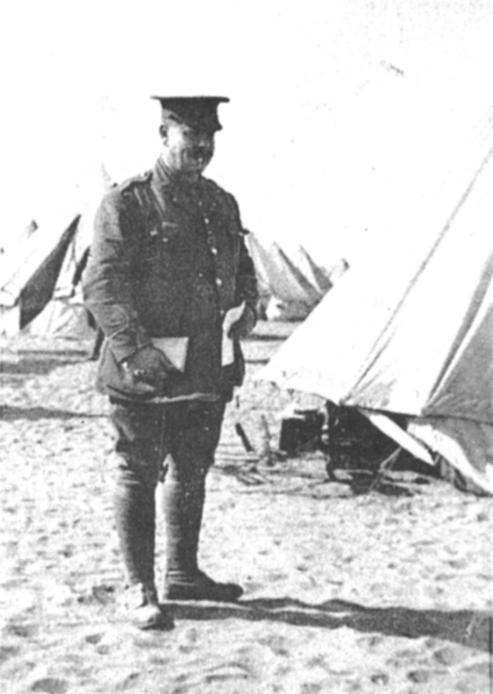

Two views of ‘X’ (District) Company going ashore at Port Said. Lt. Col. Rickman is standing on the floating platform.

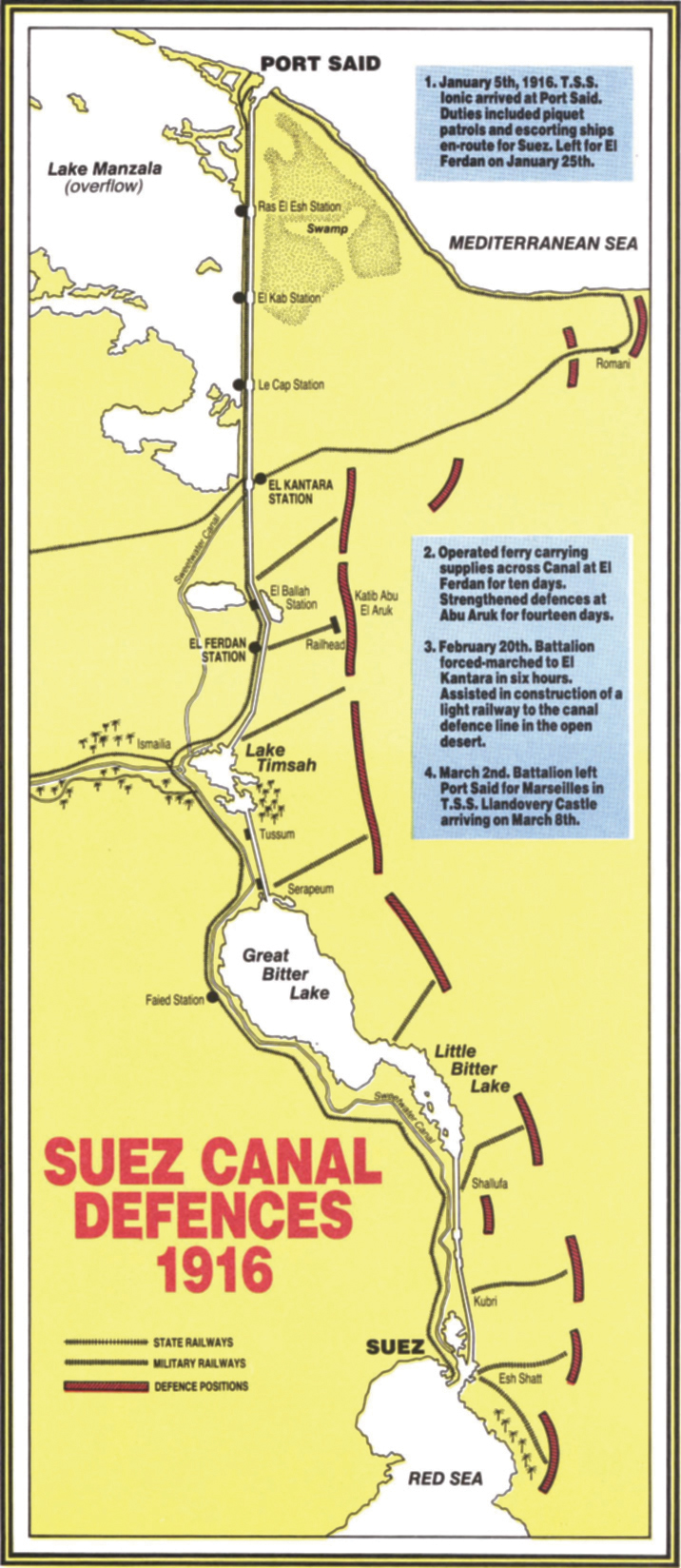

The Imperial Strategic Reserve’s twelve divisions confronted but one Turkish division bivouacked a hundred miles away on the eastern edge of the Sinai Desert. Kitchener’s remit to Murray on the role of the Reserve included, “You should maintain as active a defence as possible — to ensure no formed bodies of the enemy come within artillery range of the Suez Canal. Every care must be taken small hostile parties do not reach the Canal and interfere with its navigation.”6 The 11th East Lancs, with the rest of 94 Brigade and 31 Division, put to work to carry out these instructions.7

At first the Battalion’s duties were undemanding camp guards with occasional guards of honour for visiting dignitaries. Piquet patrols in the narrow streets of Arab Town in Port Said were less so. Ideas of a ‘romantic East’, based on childhood Bible illustrations quickly changed in the noise and squalor of the aptly named Rue Babel. Not all Port Said however was Arab Town. There were several quiet squares and tree-lined boulevards in the French style. Pte Cowell wrote to his wife, Polly “I went to church here on Sunday and although it is such a far-away country it was glorious to hear Mass said as it is at home.” Always optimistic about getting home, he continued, “I don’t think we will see any fighting here — so it is only a matter of time and then home once more.”8

Occasionally, despite Kitchener’s remit, small hostile parties peppered ships on the Canal with rifle bullets. Aimed primarily at ships’ pilots, a successful shot could cause a ship to run aground and perhaps block the Canal. Consequently a fifteen man section of troops travelled on each ship as lookouts. Parties sailed from Port Said to Suez and returned by train. This became the most popular duty in the Battalion. Pte. Snailham’s section was one:

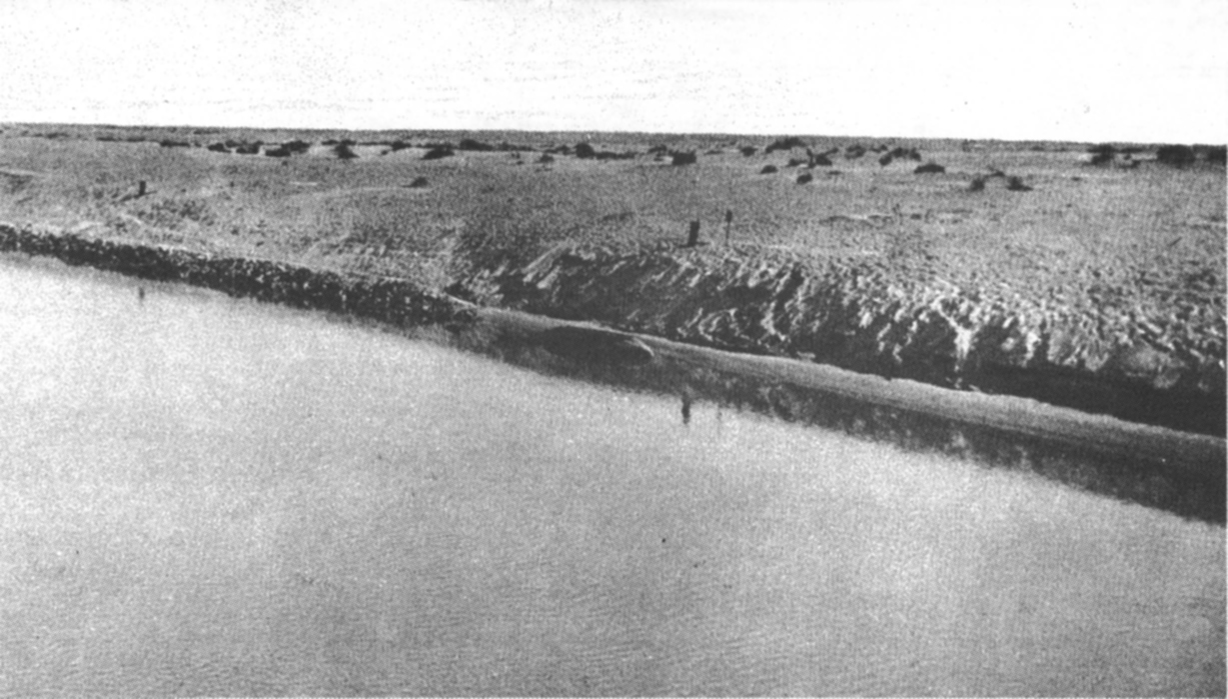

The empty desert through which much of the Suez Canal passes. At this point in February 1915 a surprise attack by Turks using flat-boats was repulsed by British forces. One of the boats still lies on the water’s edge.

Barneley Chronicle Picture Library

“A lot of us were only lads. I was still only seventeen and not worldly-wise. When we got to Suez, the ship’s captain, a Swede, said ‘Thank-you, boys. Would you care for a night-cap?’ I replied, not knowing any different, ‘No thanks, we don’t wear them!’ A quick kick on the ankle by Walt Smith, an old soldier, soon educated me!”

At the Battalion camp at Port Said a short time later Pte. Snailham happened to walk past Rickman.

Port Said railway station. The Pals were encamped half a mile away behind the station.

“The Colonel looked at me, passed on, then called me back. I wondered what I’d done wrong. He said, ‘What are you doing here?’ ‘I thought you were in the Reserves because you were under age.’ (I was amazed how he remembered me — a private soldier — from ten months before at Caernarvon.) I explained how I joined the Battalion on Salisbury Plain. I thought, ‘This is it, back to England I go.’ He looked at me for what seemed at age, then said, ‘You shouldn’t be here, you know, but we can’t do anything about it now.’ He then dismissed me. I’m sure he knew I would have been broken-hearted to be sent back”.

Rickman’s reason for allowing Pte. Snailham to stay will never be known, but he clearly had the authority — indeed an obligation — to return from active service anyone under eighteen.

Lt. Col. Rickman at Port Said.

In spite of the easy duties, life in the windy, sandy, tented camp at Port Said soon became miserable. No pay, ‘we were stony-broke;’ no mail, rumoured lost at sea; and a reduction in rations, added to the misery. On January 23rd, however, the 6th (Service) East Lancs Regiment of 13 Division, moved into the next camp. These survivors of Gallipoli had left leaving over two hundred dead mates behind and many were sick and exhausted. Although glad to be among friends and relatives most, with nerves shot, were reluctant to talk about their experiences. Their appearances — gaunt, emaciated, burnt by the sun, told its own story. Pte. Pollard’s uncle Joe was something of an exception. An ex-regular, ‘old sweat’, he seemed remarkably unaffected. “After enthralling us all with his adventures, he borrowed the little money I had Tor a drink or two’. He offered to apply for me to go with him in the 6th Battalion, but I declined, I thought I’d better stay with my mates!” Pte. Connor, however, did transfer to be with his brother.9

The reunions were cut short on January 25th, by a move south to 94 Brigade H.Q. at El Ferdan, on the west bank of the Canal. Starting at 4 a.m. they journeyed in open railway trucks, with innumerable halts and delays, in pouring rain, to reach El Ferdan at 12.30 p.m. Their baggage and tents arrived six hours later. It took another six hours to make camp and settle in. The Battalion had the task along with the 12th York and Lancaster Regiment operating from the east bank, of transferring men, horses, stores and food across the Canal. They used a heavy, flat-bottomed ferry, pulled by teams of sixteen men hauling on two chains which lay on the Canal bed. It was arduous work for men with empty stomachs. Dates or figs, on bread with no butter, with one loaf between seven men became the rule for tea. A few Huntley and Palmers biscuits and a little stew and potatoes for dinner. When sacks of raisins or dates and crates of corned beef and biscuits were unloaded from ships onto the ferry, Pte. Marshall and his companions, ever hungry, could not resist the temptation;

“Crates were ‘dropped’ and broken, and the contents pushed into the sand, to be retrieved at night. Someone on guard duty usually helped us find what we’d hidden! We finally got ‘sacked’ from that job — they said we stole more than the natives!”

‘X’ (District) Company digging in near Port Said.

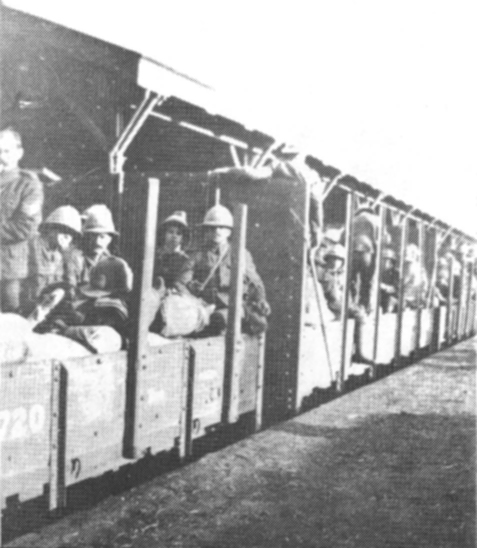

The open carriages of the Egyptian State Railway train to El Ferdan.

Barnsley Chronicle Picture Library

Setting up camp at El Ferdan. Captain Livesey knocking in a tent peg.

Lt. Ryden and n unidentified officer.

‘X’ (District) Company N.C.O’s supervise the loading of the chain operated ferry at El Ferdan.

‘X’ (District) Company men watching the Monitor H.M.S. M15 passing along the Suez Canal from Port Said to Ismalia. (The M15 was to be sunk by the U38 on November 11th, 1917).

By now the mail arrived, not as feared, lost at sea. The men received a weekly allowance of four packets of cigarettes or two ounces of tobacco and gradually supplies of legitimate food improved. The camp lay on ground rising from the bank of the Canal and rest-days were pleasantly spent watching the variety of Canal traffic — stately Nile sailing dhows and dahabiehas bringing stone from Suez; troopships en-route to and from the East, and Royal Navy gunboats and destroyers on patrol. No-one, however, mourned the end of their ten-day stint at El Ferdan when news came of a move to Abu Arak on the outer-most point of the Canal defence line, seven miles into the Sinai Desert.

At Abu Arak, a mere huddle of small, poor dwellings in the arid desert, ‘W’ and ‘Z’ Companies constructed strong-points of trenches and barbed wire. Digging trenches in the soft sand proved easy. Revetting trenches with wattle, hurdles and tarpaulins grew to be a frustrating and confounding task. They better enjoyed escorting pairs of camels dragging ‘gates’ across the front of their sector to smooth out the sand, to be followed later by the ‘dawn patrol’ to examine the cleared area for the footprints of intruders. Meanwhile ‘X’ and ‘Y’ Companies in turn, collected water supplies and materials from El Ferdan. At Abu Arak, with water restricted to one pint per man per day, the food at least improved. This didn’t stop Pte. Marshall and his ‘Z’ Company colleagues, still hungry, paying a penny each for chappatis from the Indian troops of their cavalry screen.

‘W’ (Accrington) Company Lewis Gun section pose for a group photograph.

An officer’s servant (name unknown) enjoys a quick shave.

Captain Peltzer and Major Milton share a joke.

Quartermaster Captain Smith.

Part of the camel train taking supplies from El Ferdan to Abu Aruk.

Members of ‘Z’ (Burnley) Company with an Egyptian camel drover. Pte. James Walton first right.

After fourteen days, on February 20th, the Battalion marched six hours northwards alongside the Canal to El Kantara, thirty miles south of Port Said. The men arrived exhausted in the heat of mid-day; their baggage and tents followed, eight hours later. They seemed fated, as always, to arrive at unprepared destinations. Despite the poor beginnings, El Kantara proved an enjoyable break and for a few days everyone relaxed. Many had a welcome dip in the Canal and some joked, ‘I’ll just swim to Africa and back.’ Pte. Pollard, with the Ionic torpedo incident in his mind, vowed to his friend Pte. Harry Kay he wouldn’t go back ‘over there’ (across the Mediterranean) until he learned to swim.

“We cut open sacks of emergency rations, ate the food, and from the sacking made swimming trunks (we would have been shot if anyone found out.) The Canal, at that point had a waist deep shelf about two yards wide. On this shelf, with lessons from Harry, I learned to swim. I was then quite satisfied.”

The railway junction of El Kantara was an important link in the defence of the Suez Canal. From here the Battalion now constructed a light railway to Hill 108, a point in the outer defence line in the Sinai Desert. More arduous than El Ferdan and without its compensations, the men laboured to dig cuttings and build embankments. Tragically, on February 23rd, Lt. Harry Mitchell of ‘Z’ Company, was seriously injured in an accident and died two days later.10 L/Cpl. Bradshaw and the signallers had other work.

The interior of Lt. Rawcliffe’s tent at Abu Aruk.

“We had an easy but boring job. From a tower near the railway station we kept watch for, by day, a heliograph, by night, a green lamp, situated far out in the Sinai at an outpost watching the Turks. Any message by heliography or the lamp turning red, we were to report to H.Q. Not a thing happened.”

Lt. Henry Mitchell.

A group of ‘Y’

(Chorley) Company men at El Kantara. Pte Ormond Fairweather first left front row.

By mid February, it came clear the Turks were unlikely to risk an attack on the Suez Canal across the Sinai Desert. The British High Command therefore decided by April 1916, (the beginning of the dry season) that three divisions could defend the Canal instead of the present twelve.11 As the situation in the East cleared, more troops could be spared for the more important campaigns in France and Belgium.

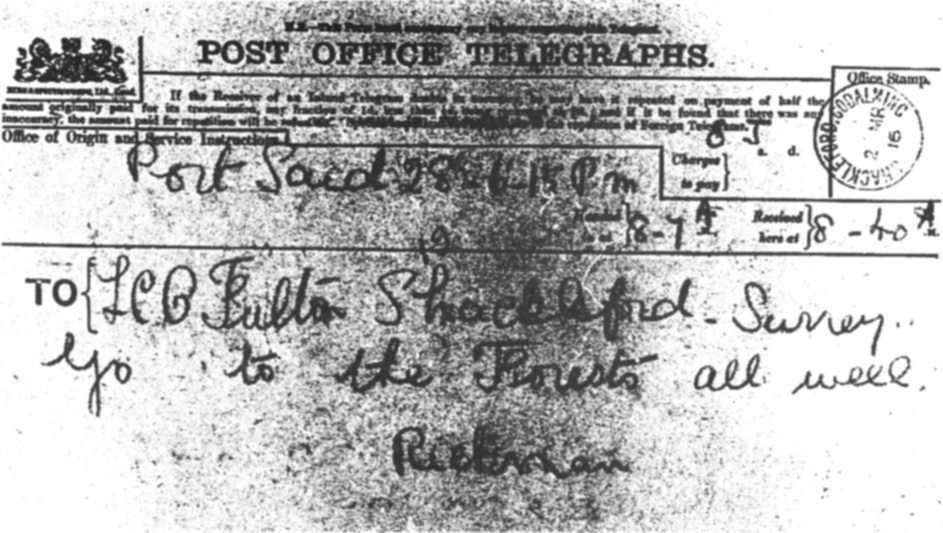

Before leaving England Lt. Col. Rickman arranged a coded message with his fiancee so she would know of his impending return. This telegram was the signal for her to prepare for their wedding. (They were married within a month).

As early as December 6th, 1915, at the second Allied Military Conference at Chantilly, held to discuss Allied operations for the coming year, Great Britain and France in a joint enterprise with Russia and Italy, decided to deliver simultaneous attacks with maximum forces on their respective fronts, ‘as soon as circumstances were favourable.’ probably in the Spring of 1916. By February 1916, this changed to June or July for a joint British and French attack astride the River Somme, where both forces met. After the Chantilly Conference the British High Command readied their full strength in men and munitions in preparation for the great offensive, with the ruling principle to place every possible division, fully equipped, in France by Spring. This released divisions in the Imperial Strategic Reserve, amongst them 31 Division, for France and the ‘Big Push.’

46 Division was the first to leave and sailed from Egypt on February 4th, 1916. On February 26th, 31 Division received its orders to embark for France. Three days later the 11th East Lancs Regiment got two short days notice to leave Port Said on March 2nd. In a letter to Harwood, Rickman described the speed of events. “We came in very hurriedly, handed in all camp stores, transport vehicles, horses and mules. (The transport drivers had already gone ahead with Lt. Bury.) We did a pretty quick embarkation leaving (‘El Kantara’ was deleted by the censor) by train at twelve noon and sailing five hours later.”12 The Battalion left behind Pte. William Baron, ill in hospital in Port Said; he later died on March 25th, 1916.13

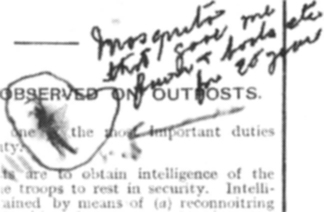

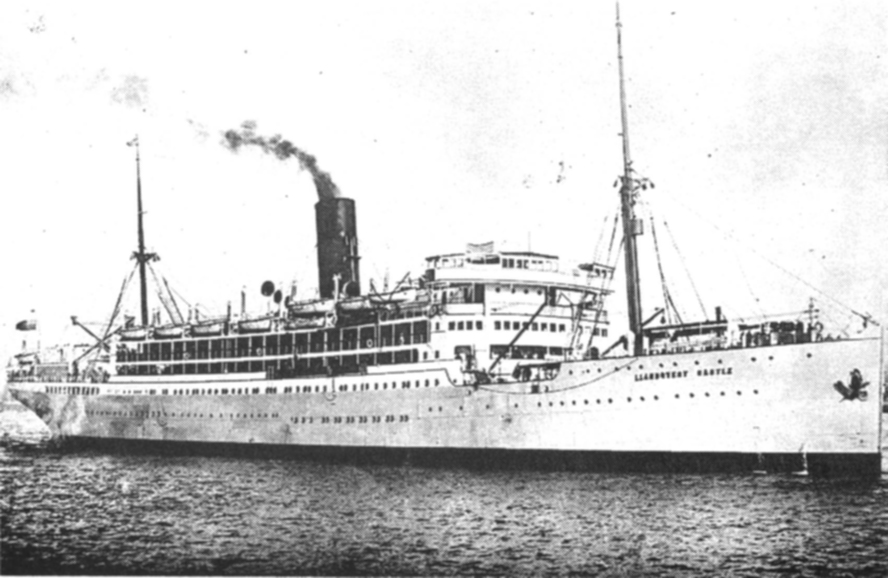

The voyage on the T.S.S. Llandovery Castle was comfortable and uneventful. For the men, after three months of hard sand, the hammocks ‘felt like feather beds.’ Officers had the luxury of a large lounge, a library and a smoking room. Pte. Cowell, optimistic as always, wrote to Polly his wife “I am expecting to be with you before long, as I am going to where — (censored), — so the chances of getting home will be a lot better.”14 Pte. Sayer of ‘Z’ Company did not enjoy the voyage. On February 29th a mosquito had bitten his wrist. ‘It was caught in the act then picked up and enmbedded in my small-book.’ After three days at sea his hand had swollen to twice its size and he had a fever. This fever, unknown to Pte. Sayer, was to recur at intervals for the next twenty years. The Llandovery Castle entered Marseilles harbour on the afternoon of March 8th. At 9 a.m. the following morning, two hours after disembarking, the Battalion entrained for the ‘Front.’15

The Battalion arrived in France fit, confident and high in morale. In spite of grumbles about trench-digging, outpost duties and poor food, they had ‘rested’ away from the rigours of a European winter. Egypt added to their life-experience and so they were tougher and more self-assured in consequence. They compared themselves, more realistically than in England, with Regular, Territorial and other Kitchener Battalions, and felt equal to any. Seeing the state that the 6th Battalion were in after Gallipoli gave them a glimpse of what war could do to men but paradoxically this spurred them on to want to ‘do their bit.’ Their ‘esprit de corps’ formed by the pre-war friendships, in which Lord Derby and Lord Kitchener had such faith, made the Pals, in their own opinion at least, the equal of any one. This belief shaped their loyalties and attitudes. Pte. Marshall described an illustration of this.

A page from Fred Sayer’s “Soldiers Small-Book” with the mosquito that bit his wrist, embedded into page 12.

The ‘Llandovery Castle’, 11,423 tons, launched in 1914. The sinking of the ‘Llandovery Castle’ on June 27th, 1918 was to be regarded as one of the worst atrocities of the war. She was sailing in the Atlantic as a hospital ship when she was torpedoed without a warning by the U-86. The U-boat then rammed or sank by gun-fire all expect one life-boat. 234 men and women died.

I.W.M.

Aboard the ‘Llandovery Castle’ March 2nd, 1916. Lt. Col. Rickman (with his back to the camera talks to Lt. Ryden (left), Capt. Riley (centre) and Capt. Watson.

“We were at El Kantara and marching past a Regular Army camp. Two men were strung up on a gun-wheel in the sun (i.e. Field Punishment No. 1, one hour each morning and evening.) ‘Potty’ Ross, (‘Z’ Company Commander) said, ‘That’s what happens if you misbehave.’ The reply came back, It won’t tha’ knows, if you did that to any of us, t’others would cut him down!”

Captain Ross’ remark may or may not have been serious, but the reply was.

Although in reality still poorly trained for their new role, all officers and men of the Battalion were glad to be in France, glad to be on their way to what they had so readily enlisted to do so long ago.

NOTES

1. History of the Great War, Military Operations, Gallipoli, Volume II Appendix 17, Page 69 Heinemann 1932.

2. History of the Great War, Military Operations, Egypt and Palestine, Note II pp 99 — 100 H.M.S.O. London 1928.

3. On January 17th, 1916, Cpl. Todd wrote from Ghain Tuffieka Convalescent Camp, Malta, to A.Q.M.S. Hindle in Egypt. “I am the voice of one crying in the wilderness. What a bleeding hole! I had hopes to get to the Battalion direct from hospital, but the C.O. said such movement must be done through Convalescent Camps and one must be classified either: I.H. (Invalided Home) L.C. (Lines of Communications) or A.S. (Active Service). I cornered the M.O. and told him I wanted to go A.S. to Egypt. After an administration of brandy, he recovered and said I was the only one who ever asked for that. He put me down A.S. straight-away. So far, so good. Yesterday a draft of Colonial troops (I.H.) left for Australia. I tried to get a passage with them as far as Egypt without success. I have written to Capt. Watson (now the Battalion Medical Officer) asking him to ask for my release as soon as possible. One of the staff here says he can easily get me I.H. on the next draft. All N.C.O’s and W.O’s seem to work that job alright. If the Captain writes the C.O. here, I think I shall escape such a fate”. (Cpl. Todd got to Egypt on the eve of the Battalions’ departure for France on March 2nd, 1916).

4. 15835 Pte. James Clarence Wixted, of Accrington, aged 24, a single man, is commemorated on the Helles Memorial, Gallipoli, Turkey.

5. The ‘torpedo incident’ caused some bitterness in later years. In 1918, the War Office decided members of the Battalion did not qualify for the 1915 Star because ‘they had not served on the establishment of a unit in a theatre of war during that year’. Many considered a torpedo being fired at them qualified them. Two formal appeals failed. As late as April 1935, Major Proctor, Accrington’s M.P., told the first Annual Reunion of the Battalion ‘he would not let the matter rest’. There is no record, however, of any further action, or applications to the War Office.

6. The only enemy submarine known to be in the area was the U38, commanded by Captain Valentine, later listed as a war criminal for shelling and machine gunning survivors of torpedoed ships. From December 27th, 1915, to January 4th 1916 he sank five British, including the ‘Persia’, and several allied ships with the loss of over 500 lives. The U38 survived the war. She was surrendered to France February 23rd, 1919 and broken up for scrap at Brest in 1921.

7. History of the Great War, Military Operations, Egypt and Palestine, Note I pp 98–99.

8. 31 Division with 11 and 13 Divisions, became part of XV Corps formed in Egypt on January 12th, 1916. XV Corps was responsible for No. 3 (Northern) Section, (El Ferdan to Port Said) Canal Zone Defences.

9. 18103 Pte. John Connor of Oswaldtwistle, aged 40, sailed with the 6th Battalion on February 13th, 1916, to Mesopotamia. He drowned crossing the River Tigris on April 10th, 1916. He is buried at Amara War Cemetery, Iraq.

10. Lt. Henry Harrison Mitchell of Blackburn, aged 29, a single man and a former insurance broker in Blackburn. He is buried in Port Said War Memorial Cemetery. Major Ross wrote to Lt. Mitchell’s parents:- “I have had the pleasure of being his Company Commander from the very first, and a better Lieutenant and comrade I could not possibly have wished for. His men were devoted to him and I can assure you we all feel his loss very greatly. He is the first officer in the Brigade to give his life for his country and we shall always hold his name in honour and reverence.”

11. History of the Great War, Military Operations, Egypt and Palestine, Note II pp 170–174.

12. A.0.18/3/16.

N.B. Rickman, using a pre-arranged code, informed his fiancee in England of his departure. His telegram, dated March 2nd, 1916, said simply, ‘Go to the florists. All well. Rickman’.

13. 15478 Pte. W. Baron, ‘X’ Company, was married and lived in Rishton. He is buried in Port Said War Memorial Cemetery.

14. Postcard, Egyptian scene, dated March 8th, 1916. Written at sea, posted Huppy, Northern France, March 12th, 1916.

15. 31 Division was the second of five divisions to leave Egypt for France during the first quarter of 1916. The men of 31 Division firmly believed that they left Egypt in order of military efficiency. Only the experienced 46 (North Midland) Division (Territorials), who left on February 15th, were deemed to be better than they.