Chapter Seven

God help the sinner

At Warnimont Wood on the morning of June 30th, each company held a final sick parade. A medical orderly visited those unable to attend, Pte. Pollard was still ill in his bed.

“I could hear him coming, calling at the huts before he got to mine —‘medicine and duty.’ ‘medicine and duty.’ Then he appeared. He looked around. ‘Everyone in here, medicine and duty, except Pollard — and the ambulance is coming for him.’ I was left in my bed, alone in the hut. I hadn’t seen a doctor for three days.”

The detailed final preparations continued. Each man tied onto his haversack a small triangle cut from a biscuit tin. On his shoulder he tied a three inch wide strip of cloth, appropriately coloured for his particular wave. In theory the metal and colours were to assist observers to identify each wave and so monitor progress over the enemy-held ground. All this part of the minutiae of detail developed by Divisional and Corps staff trying to legislate for every contingency. Even the two men per Company detailed to carry, in addition to their normal load, ‘a maul or mallet’ wore a separate distinguishing yellow armband. The detailed, complex orders designed so that no one, attacking infantry-men, company commanders, artillery observers et al, should lack anything, proved a burden in more ways than one. The desire of ‘staff to leave nothing to chance, neither in quantity of material nor in men’s behaviour, was to have disastrous consequences. Meanwhile men occupied themselves with the more prosaic tasks of bayonet sharpening and rifle cleaning.

In the late afternoon, the Battalion paraded for the last time. Col. Rickman read a message from the ever-optimistic Lt. Gen. Hunter-Weston, “My greetings to every officer, N.C.O. and men of the 31st Division in the coming battle. Stick it out, push on, each to his own objective and you will win a glorious victory and make a name in history. I rejoice to be associated with you as Corps Commander.”1 Col. Rickman added his own assurances. He reminded the men of the Battalion’s origins, the towns and villages the people they represented, and what was expected of them on the morrow. With a final “Good Luck,” and, “we will soon be on our way to Berlin,” he dismissed them to their last meal and rest before leaving. For Col. Rickman with his own inner doubts, and for many of his men, with their’s, it was a telling moment.

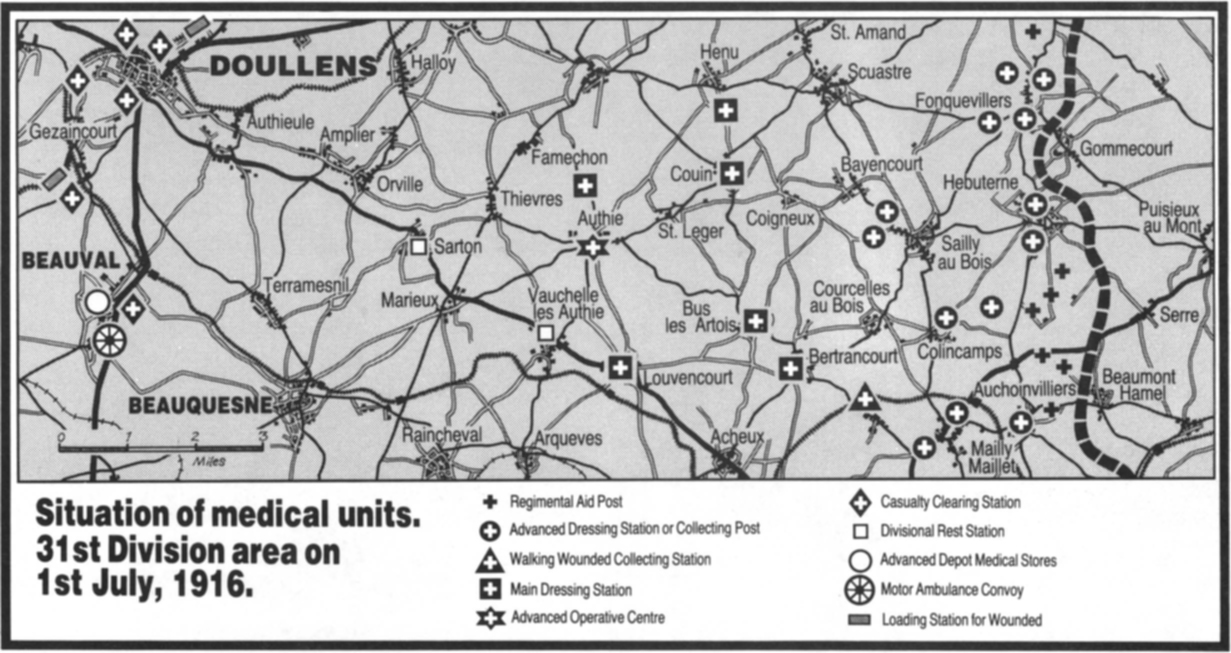

Pte. Sayer missed the occasion. In concession to his state of sickness he left, with Captain Riley’s permission, at 2 p.m. to make his own way to the front line. He later realised he possessed neither pass nor written authority to show why he was alone. He was never challenged. He was after all walking in the right direction. At 6.15 p.m. the Battalion moved out of Warnimont Wood to begin the seven mile march, via Bus les Artois, Courcelles and Colin-camps, to their front line positions before Serre. Pte. Pollard was moved from his bed to the roadside and lay awaiting transport to Gezaincourt (near Doullens) five miles to the rear. As ‘W’ Company marched by, his friend Pte. Place handed him his cap-badge, asking him to give it to his mother if he didn’t come back. Pte. Place, newly returned from hospital, went up to the line for the first time in two months.

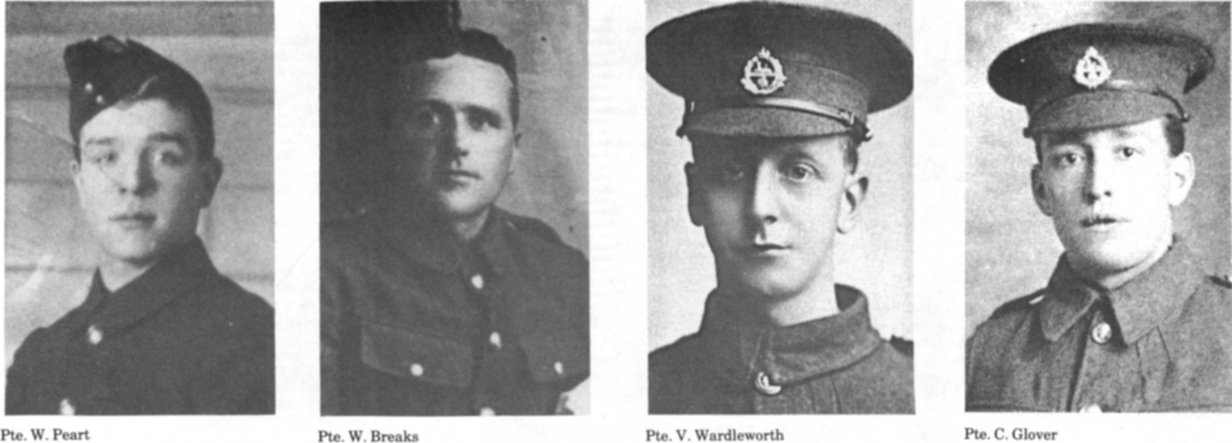

Behind the British lines on June 29th, 1916. The scene on the road between Mailly-Maillet and Colincamps as final preparations are made for the Big Push.

I.W.M. Q737

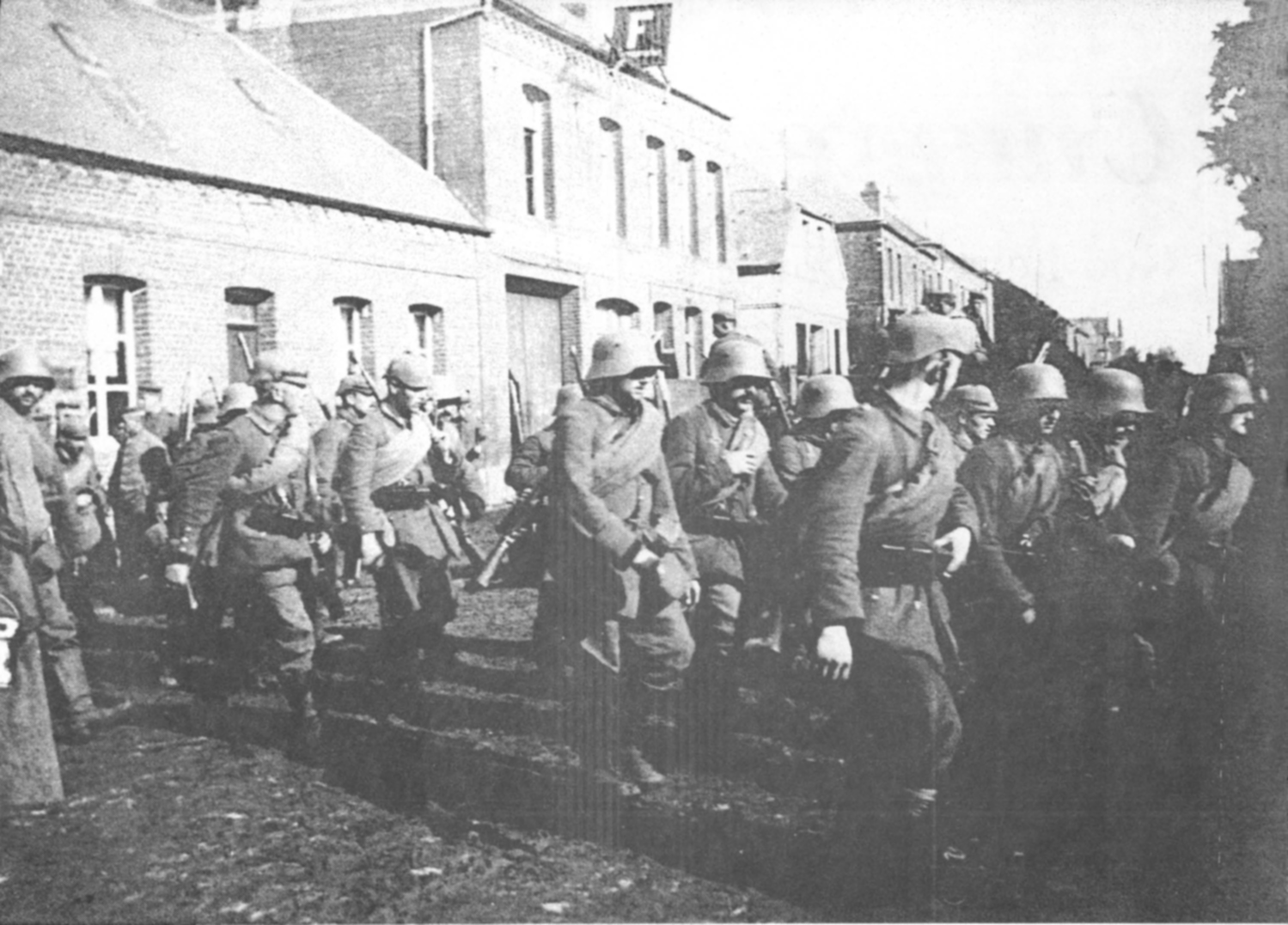

Behind the German lines. 169 Infantry Regiment troops move up to the front line after resting in the village. Note some wear spikeless covered Pickelhauben whilst others wear the steel helmet. Note also the rolled blankets worn crossed over the left shoulder.

R. Baumgartner

Through Bus les Artois then ‘overland’ through fields on a route marked by white-tape the Battalion marched to Courcelles. Those few villagers who had decided to stay watched silently as they passed. Just outside the village the Battalion encamped in a lane, where they had hot tea and hard biscuits and rested in the sunshine of a perfect, balmy, evening. After the meal each man received five bars of chocolate, a box of matches — and a sausage. The incongruity of this made men suspicious. Thinking they might have been drugged to ease the fear of going over the top, no one would eat them.

Pte. Sayer got his sausage at ‘Z’ Company’s field kitchen. ‘It reeked of garlic or something so I hung it on my haversack out of sight. Most people threw them as far away as possible!’

Each man also received a final addition to the already cumbersome burden of Field Service Order (with haversack only) a bandolier of S.A.A. (Small Arms Ammunition), gas-helmet, groundsheet, water-bottle and iron rations. Also there were four empty sandbags, to be used in trench repair on consolidation; two Mills bombs for the later reserve supply to bombing parties; entrenching tools (two men to carry shovels to every man carrying a pick) and for some unfortunates, a roll of barbed wire.2

Specialists had their own burdens. Each bombing party of eight men, for example, collected “100 Mills bombs and 25 rifle grenades with cartridges and detonators in Bucket Bomb Carriers, each party using six buckets for the purpose. Each party will, in addition, carry two empty bomb buckets to collect bombs from the men carrying the reserve supply.”3

With all issues complete the Battalion with Col. Rickman at its head, left Courcelles at dusk. They marched through Colincamps on to the half-mile straight stretch of poplar-lined pave road leading to the shattered remains of the Sucrerie. They made slow progress through the congestion of troops, horses and vehicles as other units made their way to their own places in the front line.

The men entered the Sucrerie in single file and entered the communication trench. The British artillery bombardment had temporarily eased, but the familiar battery of ‘eighteen pounders’ fired as they filed past. L/Cpl. Marshall thought of his first time along the same trench. He wondered what happened to the Accrington sergeant who had been thrown into a state of shock when the Battery had fired. “Better off than me, anyway,” he mused. A more optimistic Pte. Hindle, of the Concert Party and ‘X’ Company later wrote, “You can judge how cheerful we were. On our way in the trenches we passed the Royal Field Artillery Battery. One of our chaps said, ‘What do you want bringing back — a German helmet or an officer’s watch?’ Jokes abounded. We all promised each other a drink in the village of Serre.”4

The journey along the communication trench aptly named ‘Excema,’ although a tributary was ‘Zambuk’, became a nightmare. The men fell silent and apprehension took hold. At the junction with Sackville Street, every mans’ head turned to look at a large open common grave, dug by the 12th (Service, Miners Pioneers) K.O.-Y.L.I. the Pioneer Battalion of the Division, at the side of the new R.A.M.C. Advanced Dressing Station in Basin Wood. Quantities, only to be guessed at, of wooden crosses were stacked outside a wooden hut.

Loaded as they were, men struggled along the narrow congested trench. “I had round my neck two sandbags filled with Lewis gun drums. They alone must have weighed forty pounds.” (Pte. Kay). In places, because of heavy rain, muddy water rose above men’s knees. Each traverse brought bunching and confusion as men struggled round corners. Those who fell needed the help of their comrades to regain their footings. “We struggled; Nansen, Peary and Scott struggled no less.” (Pte. W. Clarke). Telephone wires strung along and across trench sides became an added abomination.

A party of British bombers move up to the front line.

B.C.P.L.

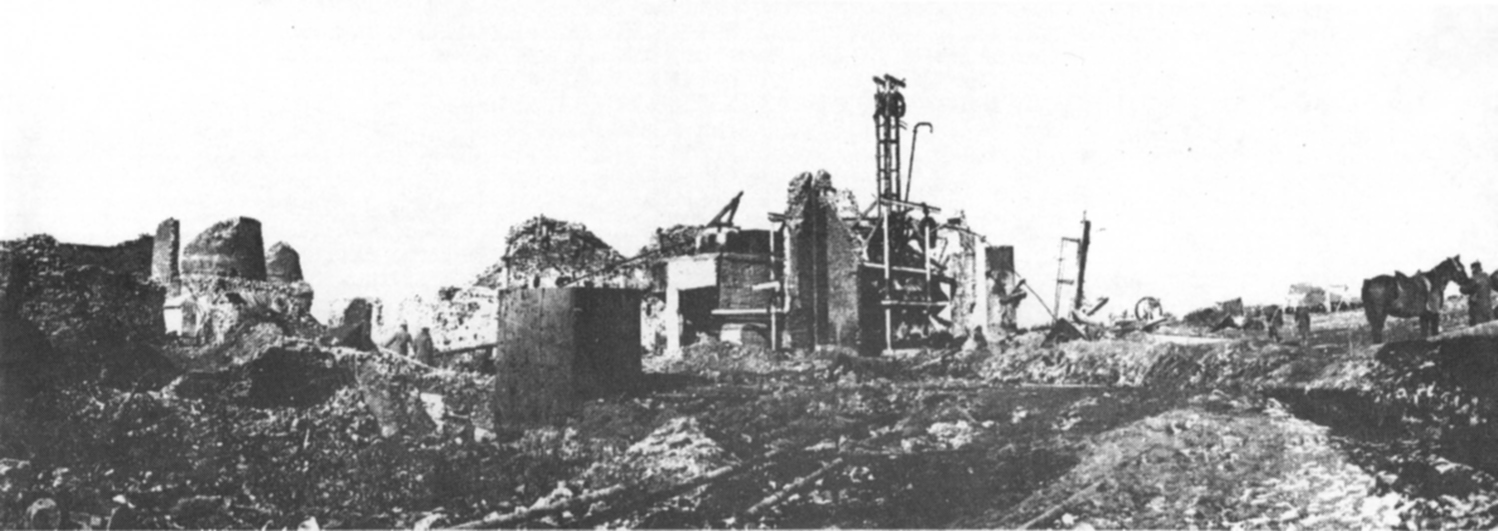

The Sucrerie. Here began the nightmare journey through the trenches up to the front line.

I.W.M. Q1815

Frequently, ‘normal’ difficulties turned to chaos as other units got lost as direction signs and tapes disappeared. Working parties on trench repair held up progress. Officers became agitated as they fell behind their scheduled time. Fortunately, throughout the night, only a desultory enemy shell-fire intervened. In the minds of the men, at least the German trenches and wire had been ‘getting summat’ in the past few days, which would eventually make their own job easier.

The last thousand yards or so from Observation Wood to the splintered remains of Matthew and Mark Copses lay on a downward slope and the going eased considerably. At 2.40 a.m. with great relief, the Battalion reached the blown in, waterlogged traffic and front line trenches.

Minutes after Col. Rickman formally took over from the 10th East Yorks Regiment of 92 Brigade, Brigadier Rees decided the blown in trenches were too badly damaged to accommo-date the first wave and ordered the whole attacking force back one trench.5 Moving the lines of tired, grumbling men into their new positions created further chaos and exhausted the men. It took until 4 a.m. and daylight before all were in place. The journey from Warnimont Wood to Matthew Copse, seven miles as the crow flies, had taken almost ten hours. The Battalion War Diary recorded the cryptic entry:- “6.15 p.m. marched via Courcelles to positions in assembly trenches, arriving in position 4 a.m. 1/7/16.”6 Pte. Sayer, in ‘Z’ Company’s dug-out/bomb-store, and now with Ptes. Rountree and Pickering, also ‘unfit for duty,’ did not know that with the move back one trench left them forward of the first wave until 7.20 a.m.

Brig. Gen. Hubert C. Rees D.S.O.

I.W.M. 51889

At this time, 720 men of the Battalion were disposed over a frontage of some 350 yards as follows:-

| First Wave:- | Two platoons each of ‘W’ and ‘X’ Companies under Captain A. B. Tough, occupied numerous bays of the front and traffic trench between Matthew and Mark Copses. |

| Second Wave:- | The two remaining platoons of ‘W’ and ‘X’ Companies under Captain H. Livesey in Copse Trench. |

| Third Wave:- | Two platoons of ‘Y’ and ‘Z’ Companies under Lt. G. G. Williams in Campion Trench. |

| Fourth Wave:- | The two remaining platoons of ‘Y’ and ‘Z’ Companies under Captain H. D. Riley in Monk Trench.7 |

The remainder, i.e. two officers and sixty men in reserve, the transport section and cooks, etc., and those detailed for carrying forward food, water, ammunition, etc., after the advance waited at Courcelles.

The open secret of the 7.30 a.m. zero hour confirmed, the men settled down to await the next three hours. Both British and German shelling, intermittent all night, eased off. Men with nothing to do huddled in any funk-hole or dug-out they could find. With neither blankets nor greatcoats (left behind at Warnimont Wood) they tried to snatch some sleep. Officers and N.C.O.s checked and re-checked their battle orders. From habit or instinct men checked and oiled their rifle bolts again and again. Lt. Rawcliffe with his men struggled to set up the Stokes mortar positions in readiness for his own zero hour of 7.22 a.m. Somewhere behind the lines Pte. Clark and his three colleagues sheltered in their ‘dump’ still forgotten, still afraid to move.

As the four waves rested, German artillery fire of every calibre intensified. The German observation posts on the rising ground on which stood Serre village, overlooked the whole of 94 Brigade front and assembly trenches. At day-light the Germans knew of the impending attack. The gaps in the Brigade’s own wire and the white tapes laid on No Man’s Land overnight as guides for the attacking waves could be easily seen from their lines.8

The German artillery, which in theory should have been destroyed by the ‘counter-battery.’ i.e. locating and knocking out enemy artillery, part of the British bombardment, quickly found the range of the front and assembly trenches. More German guns, not used until then to prevent British observers spotting them, joined in. Machine-guns added to the barrage and sprayed the front line parapets.

Lightly camouflaged German artillery.

B.C.P.L.

As the shells burst in and around the crowded trenches — “they were throwing most of Krupps at us” — the men sprawled on the floor, pushed themselves against the trench sides and took what limited cover they could. Inevitably some were hit and well before zero hour a steady trickle of wounded made its way to the Regimental First aid Post in Excema Trench, then on to the Advanced Dressing Station at Basin Wood.

The interminable wait passed in different ways. Small groups quietly sang favourite music hall songs together, others, ignoring Brigade orders, sat and smoked.9 Each N.C.O.’s small bottle of thick black rum passed between those who wanted it. Many men prayed silently and thought of home and loved ones. Some even tried to sleep. Yet others, remembering it was Saturday with weather perfect for cricket, bantered each other about their respective home team chances in the Lancashire League matches in the afternoon. Accrington, the League leaders were to play Rishton, Burnley to play Church, and rivalry between supporters often got intense.10 During the wait, Pte. Tom Coady the devout, comical doyen of the Concert Party, died instantly when a machine-gun bullet hit him in the head.11

At 6.25 a.m. complying with their week-long time-table, the British artillery started to bom-bard the German trenches intensively. Until the barrage lifted at 7.20 a.m. the men endured a colossal, tumultuous cannonade of shells rushing and whining overhead to crash onto the enemy lines three hundred yards away. In time the noise became almost unbearable. It seemed to those waiting, that there could not indeed ‘be a rat alive’ in those trenches.

As 7.20 a.m. approached the Battalion first wave received the order to ‘fix bayonets’, then with nerves tense the men watched and listened for Captain Tough’s signal to move out of the trench. C.S.M. Hey suddenly walked along the trench, revolver in hand, and pulled aside the makeshift covers over dug-outs looking for ‘skivers.’ “He had no need to do that — all the lads were ready to go.” (Pte. Bewsher).

At 7.20 a.m. precisely the British bombardment stopped. Captain Tough blew his whistle and after hastily shaking hands and wishing each other good luck the men went over. Handicapped by the weight and bulk of their loads (supposedly 66lbs but often much more) they struggled up ladders and steps and made for the narrow gaps cut in their own wire. As quickly as they could, under a hail of German shellfire they advanced into No Man’s Land. Captain Tough was wounded immediately, but urging the men on, he led them to their positions one hundred yards forward of the trenches. They laid down and waited — in the ‘shilling seats,’ as they had been christened during training at Gezaincourt.

It was not going to be like Gezaincourt, however, and it was desperately clear the British bombardment had failed. In the face of unexpected heavy fire there was no plan, nor indeed desire, to do anything other than carry out the rehearsed battle orders. For the time being, those in the shilling seats, forward of the German shells raining on the trenches, were com-paratively safe. “I felt more at ease when we got over than I ever had in the trench.” (Pte. Hindle) They were past the critical first test of courage in climbing over the parapet in the face of shell fire aimed directly upon them.

Men reacted differently to this supreme test. Pte. Bewsher, ‘number one’ in his Lewis gun team on the extreme right of the Battalion (the next man to him was in the 15th West Yorks, Leeds Pals) treated it as another training exercise and felt inwardly calm. C.S.M. Hey appeared to be unable to move until encouraged by Captain Tough, but then was immediately wounded in the arm and leg. Most men were as Pte. W. Clarke; later in a letter home he wrote: “At 7.20 a.m. with a prayer commending my soul to my Heavenly Father’s keeping, we sprang up and climbed out of the rapidly disappearing trench (we weren’t getting it all our own way) and doubled forward to be greeted by a murderous fire. How gently my comrades fell to earth! What was left of us got down in position. I looked round and to my utter surprise I saw moving human beings.”12

Capt. A. B. Tough

Capt. H. Livesey

Lt. G. G. Williams

Capt. H. D. Riley

It was the second wave Pte. Clarke saw as they left Copse Trench at 7.22 a.m. and entered the front trench. At 7.25 a.m. led by Captain Livesey, with walking stick in one hand and revolver in the other, they advanced under heavy fire and lay in position fifty yards behind the first wave. Also at 7.22 the Stokes mortars of the Brigade Trench Mortar Battery started their barrage. For ten minutes, each of the four mortars fired over twenty five bombs per minute. At the same time Col. Rickman, Major Reiss and Captains Peltzer and MacAlpine moved into the Battalion H.Q. in ‘C’ Sap.13

A German shell burst close to the British trenches.

B.C.P.L.

In spite of the British Stokes mortar and artillery barrage, German shells and bullets continued onto the Battalion front line and assembly trenches as the third and fourth waves awaited the signal to go at 7.30 a.m. Amongst the awful noise at least one man slept, overcome by exhaustion. Pte. Roberts, of ‘Z’ Company, in Mark trench, later wrote home: “As the bombardment went on and we were waiting, men were smoking and joking. I squatted down, as miners do, and fell asleep. I woke to see Captain Riley leaning against the trench side. He said, ‘Sleepy, Roberts?’ and as I said ‘Yes, Sir,’ he was called away as a shell had burst a few yards away. I never saw Captain Riley again.”

It is highly probable this was the shell which killed Pte. Arthur Tyson and wounded his brother-in-law L/Cpl. Nixon. The men were in a group of bombers. Sgt. Ernie Kay got to the scene first. “Arthur was lying there in the trench — his face had a lot of loose dirt on it and I noticed he had difficulty in opening his eyes. I asked him how he felt. He told me he was ‘easy’ but thirsty. I borrowed a water-bottle from a man nearby and wiped Arthur’s face. He was quite cheerful and not in any pain, though I could see he was badly hit. It was then 7.26 and I had to lead my platoon at 7.29. Before I left him I told him it would be some time before he could be moved. He said it didn’t matter, it would be alright. He thanked me as I was leaving, though he was quite helpless.”15 Pte. Tyson died a few minutes later.

“As ‘Z’ Company moved out of Monk trench into the front line, L/Cpl. Marshall saw his constant friend from Burnley Lads Club days, Sgt. Ben Ingham being carried from the trench. “I knew he had been killed.”

At 7.20 a.m. before Serre, as on the whole of the British front the Stokes mortars and artillery lifted their fire. For a few minutes there was silence as the artillery gunners elevated their gun-sights to locate the German second line. In those vital few minutes the German infantry, alerted by the sudden cease-fire, came from their safe, deep dug-outs and bunkers and with machine-guns and rifles manned their front line.16

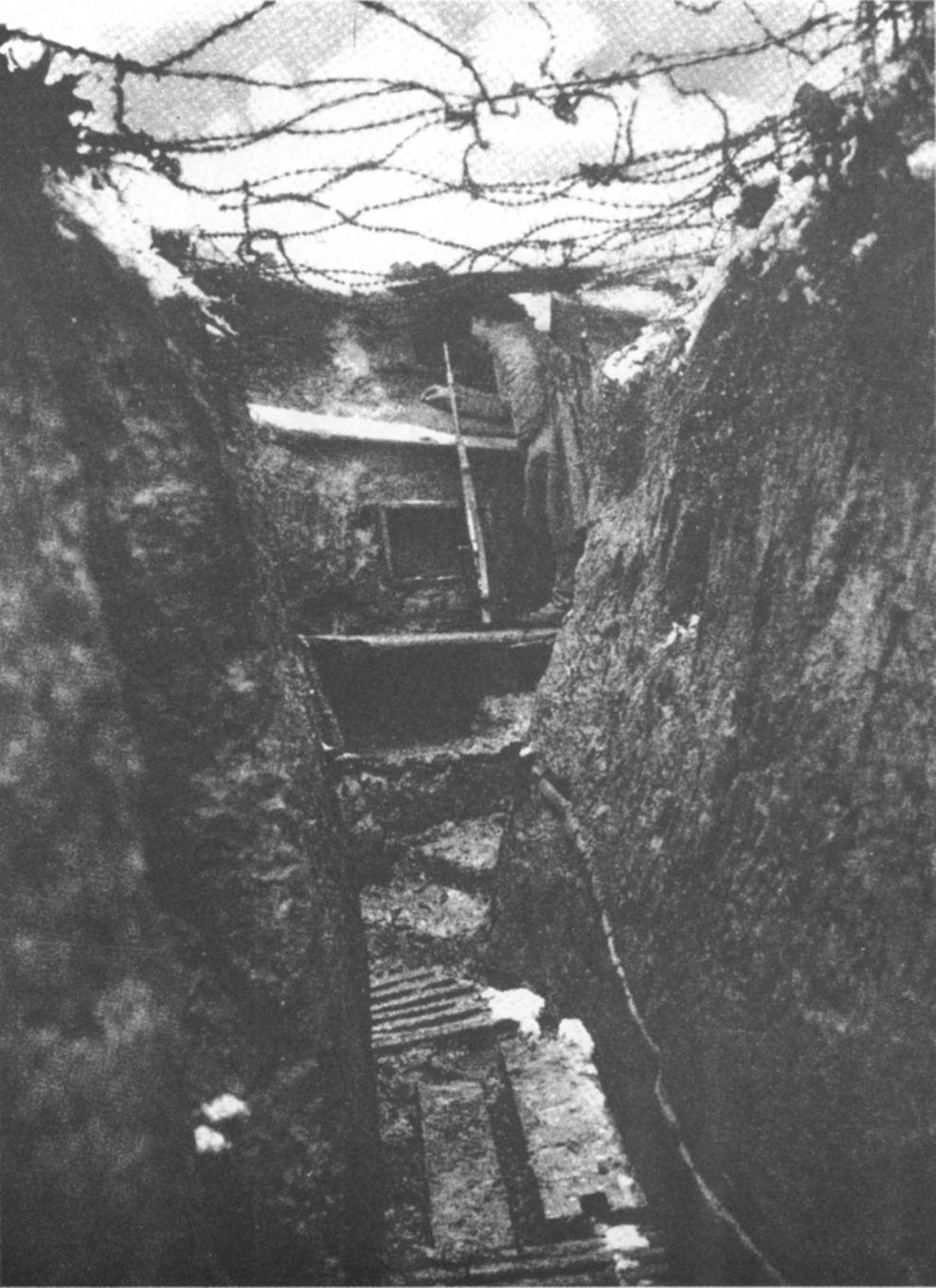

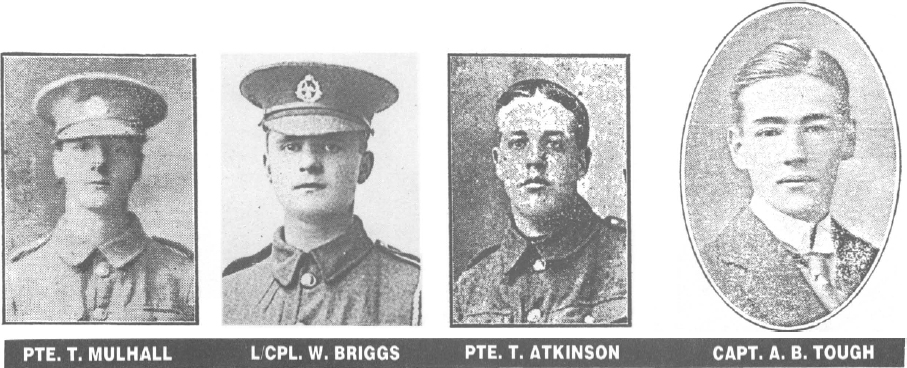

A German sentry in a wet and muddy trench looks out towards the British lines.

B.C.P.L.

The terrain before Serre 1916. The view from the British lines south of the 94 Brigade sector.

I.W.M.Q48152

At the precise moment of 7.30 a.m. signalled by whistles and shouts of encouragement by their platoon commanders, all four waves rose up and moved forward. They walked, ‘dressing to the right’, up the grassy slope towards the enemy positions, leaving their dead and wounded scattered in No Man’s Land and huddled in the trenches. Lt. Rawcliffe and his Stokes mortar teams took what rest they could after firing 1100 rounds in less than ten minutes.

In the face of continuing German artillery fire and now heavy machine-gun and rifle fire, the waves continued their advance.

“I saw many men fall back into the trench as they attempted to climb out those of us who managed had to walk two yards apart, very slowly, then stop, then walk again and so on. We all had to keep in line. Machine-gun bullets were sweeping backwards and forwards and hitting the ground around our feet. Shells were bursting everywhere. I had no special feeling of fear except I knew we must all go forward until wounded or killed. There was no going back. Captain Riley fell after thirty yards. I didn’t see him killed, but I knew immediately. When we stopped once, the message passed down the line, from man to man —‘Captain Riley has been killed’.”(L/Cpl. Marshall).

As the waves moved forward they were quickly torn apart by enfilading machine-gun fire from the direction of Gommecourt Park on the Battalion’s left. The guns were in much greater strength than realised but there was a simple answer — when the Germans saw 143 Brigade of 48 Division on 94 Brigade’s left were not attacking, they quickly turned their artillery and machine-guns to enfilade the attack of 94 Brigade.

Moments after the first wave moved forward Captain Tough was wounded a second time. A few minutes later he was killed outright, shot in the head. At 7.39 a.m. Lt. Col. Rickman reported to 94 Brigade H.Q. by runner (the telephone lines were already destroyed) that his first two waves had crossed ‘according to time-table’ and that there was still intense German fire of all description. By 7.50 he reported all waves gone forward and heavy machine-gun fire was still coming from the north (Gommercourt Park).

At least two Maxim machine guns ‘M.G. Kaiser’ and ‘M.G. Schloss’ faced the Battalion. Unteroffizier (Sergeant) Fritz Kaiser and his team fired at the advancing Pals up to twenty metres range in spite of four men wounded and one killed. The machine gun later jammed and had to be replaced. On Kaiser’s right, Unteroffizier Schloss and his team fired until the firing-pin broke. No sooner were repairs completed than shrapnel hit the gun casing, putting it out of action. ‘In order not to let the machine-gun fall into enemy hands the service team of the M.G. took it to Leutnant (Second Lieutenant) Bayer in the third trench, where a makeshift repair was carried out. Lt. Bayer, together with the service team, returned it to the first trench. There the M.G. continued firing.’17

A ration party brings food and water to German troops in the trenches. B.C.P.L.

By now the survivors of the first wave with those of the leaderless second wave were mixed together and yet split into small groups each struggling to go forward to the German front line. Capt. Livesey, with his orderly, Pte. Glover and several others, got through the German wire and into the front line trench.

“Five Germans came from nowhere, the Grst of whom hurled a bomb which grazed Captain Livesey’s face but didn’t explode. Captain Livesey shot at the group with his revolver. More Germans came so Captain Livesey and I made for a shell-hole just as a shell landed nearby. I must have been knocked out. When I came round I looked for Captain Livesey but couldn’t find him. At length I gave him up as lost. I was wounded but felt myself lucky to be alive. My cigarette case had turned a bullet which made a slight wound in my side and my gas-helmet had stopped another from doing much damage. I was also wounded in the thumb.”18

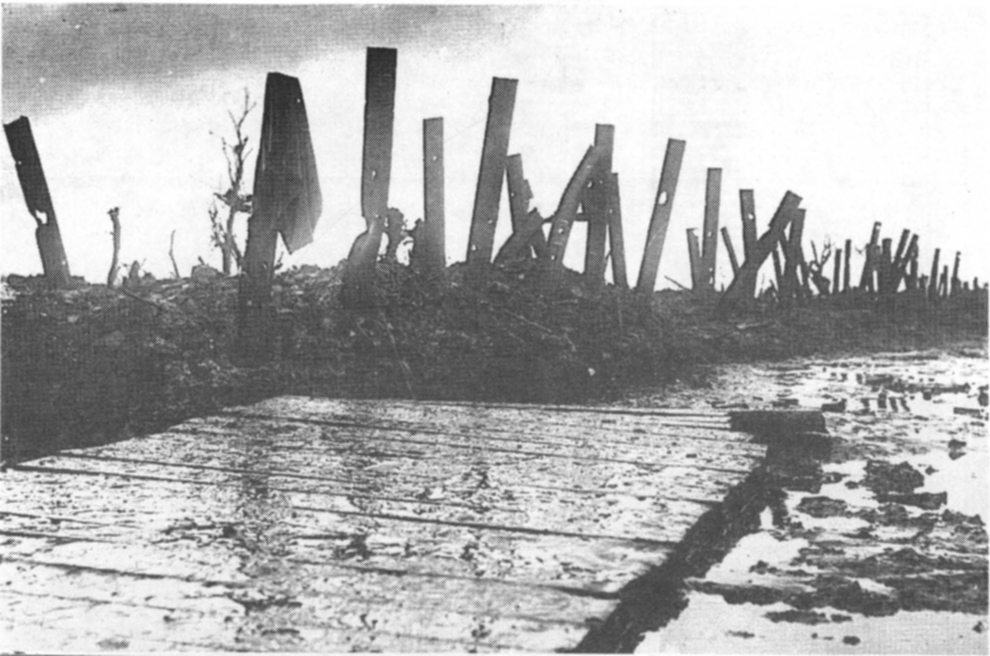

Serre Village after the artillery bombardment. A photograph taken in February 1917 after British troops finally entered the village.

I.W.M.Q1909

The German infantrymen facing the Battalion fought courageously. Oberleutnant (Lieutenant) Emil Schweikert, commanding 6 Company, although almost immediately wounded in the head by a shell splinter, kept command until the first wave of Pals was broken. Later, as the small parties of Pals continued their attack, he stood high on the side of the trench ‘half-bandaged, with a naked upper body and heavily bloodied bandages’ leading the firing and encouraging his Company. Only after an hour, after much persuasion, did he go to the rear for medical treatment. Forty year old Landsturmer (Private) Freidrich Essig was wounded in the right arm shortly before 7.30 a.m. Unable to use his rifle, and in severe pain, he supplied his comrades with ammunition and hand-grenades during the attack. He also reluctantly went to the rear for medical treatment.19

Most German trenches were deep and wide. Here a timber built observation post is incorporated. B.C.P.L.

Hans Amann — a soldier of 169 Infantry Regiment. He enlisted in August 1914 at the age of seventeen. By 1916 he was the longest surviving member of his company. All others were either dead or prisoners. He was four years on the Western Front and came through without a scratch. His mother believed he had special luck because he was born on Christmas Day. Hans Amann finished the war with the rank of Vizefeldwebel.

R. Baumgartner

When Col. Rickman made his report at 7.50 a.m. he knew the attack had failed. From that moment he could only watch in despair the slaughter of his Battalion. The past fifteen months of his life, since his celebrated entry into Castle Square, Caernarvon on St. David’s Day 1915, had been devoted, not simply to train a New Army Battalion for its role in battle, but to the well-being and care of men whom he knew represented the best in camaraderie and fellow-feeling. Those friendships formed in pre-war days in factories, mines, offices, Sunday Schools and sporting-clubs were matured and shaped through his military discipline and training into a battalion equal to any in the New Army. Col. Rickman now impotently watched its destruction.

As Col. Rickman anxiously awaited reports from ‘his waves’, hundreds of dead and wounded men lay in No Man’s Land — the wounded left behind by comrades pushing forward. Now the elaborate battle plans had been literally blown apart, it was up to individuals to survive.

“While we were walking in line, my section came to a shell-hole. We had to decide which way to go round. Some went to the left I went to the right. A shell came over and I was thrown to the ground by the blast of the explosion. I picked myself up and realised I had a flesh wound in the leg. I looked around and to the left of me was nothing — not a man. For fifty yards on either side, no other man was going forward, only dead and wounded on the ground. I went forward about twenty yards and again was wounded, this time in the arm. The wound was quite bad. My hand dropped and was useless. I remember it felt cold. I thought ‘I’m not going forward with this hand, I’d better get back and get a dressing on it’. Then another shell burst and knocked me over.

“I was still lying prone on the ground when a piece of shrapnel hit me behind the ear. I slipped into a shell-hole about 25 yards from the German front trench, wiped away the blood and pulled the shrapnel out. Creeping forward I spotted some Germans. I fired just one shot. Then, thud! I thought my head was blown in two. I was blinded with blood”. (Pte. Clarke). “I was blown off my feet twice but got up unhurt each time and carried on. Suddenly, I don’t know how, where or when, such was the clamour and confusion, a piece of shrapnel went into my hand. It must have struck my rifle at the same time. I just stood there, in complete surprise and watched my rifle go up into the air, spinning over and over. My hand felt dead, and quite calmly — I wasn’t a bit afraid ) I thought ‘It’s no good I can’t do anything now, I’d better go back. I looked around me and I was by myself, there was nobody there.” (Pte. Fisher).

“We advanced about eighty yard or so in a small group separated from the rest. We got so near to the German wire that they were throwing grenades at us. I got hit in the leg and I made for a shell-hole and dived in it. They must have known I was there because they kept throwing grenades in. I was on my own. I could see no signs of anyone else. I looked again and saw some Germans coming towards me. A shell exploded right on them. I got another flesh wound in the leg. It was cruel for them but lucky for me. It gave me a chance.” (Pte. Anderson).

Pte. Kay had a similar experience.

“My job in the attack was to follow my No. 1 on the Lewis gun team and supply him with the drums I carried round my neck. The Germans had their machine-guns on us as soon as we were over the parapet. We waited for our artillery to lift their fire from the German front to the second line. We got as far as their wire and I was wounded in the leg. My Corporal, Sam Smith, was killed outright A piece of shrapnel went right through his entrenching tool. I dropped into a shell-hole with Pte Bill Bowers. We were no sooner in there than the Germans threw stick-grenades in at us. I caught a wound in the arm.”

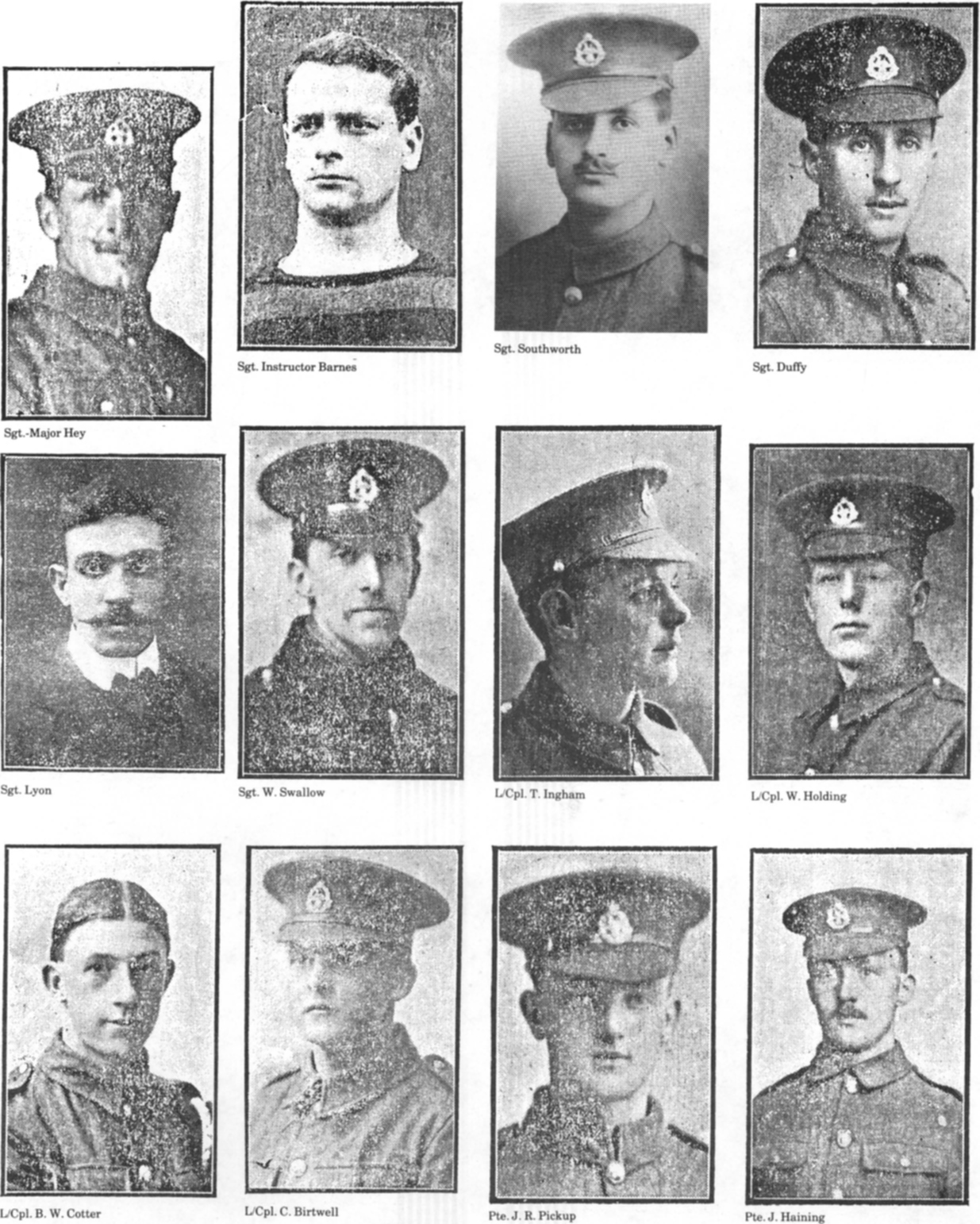

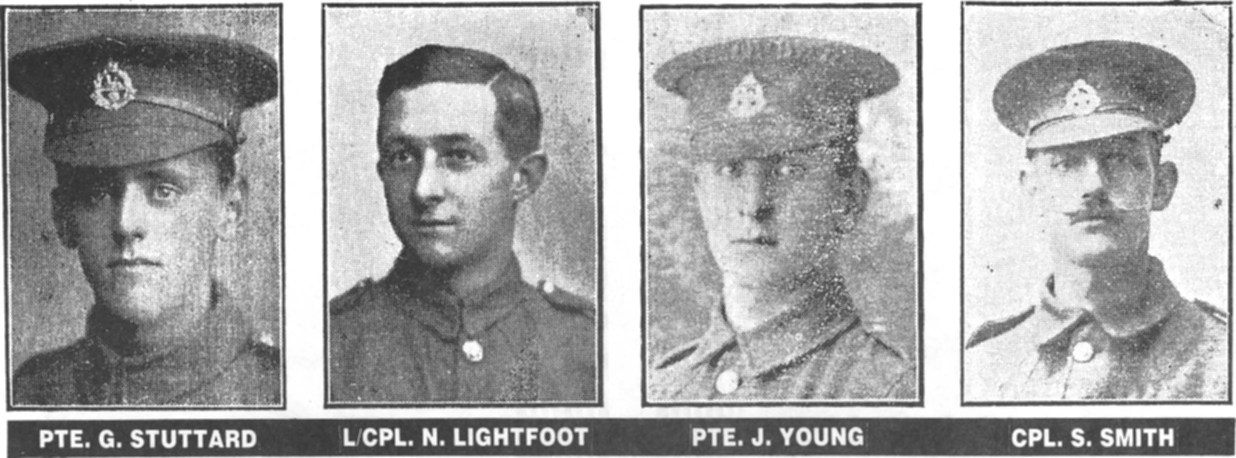

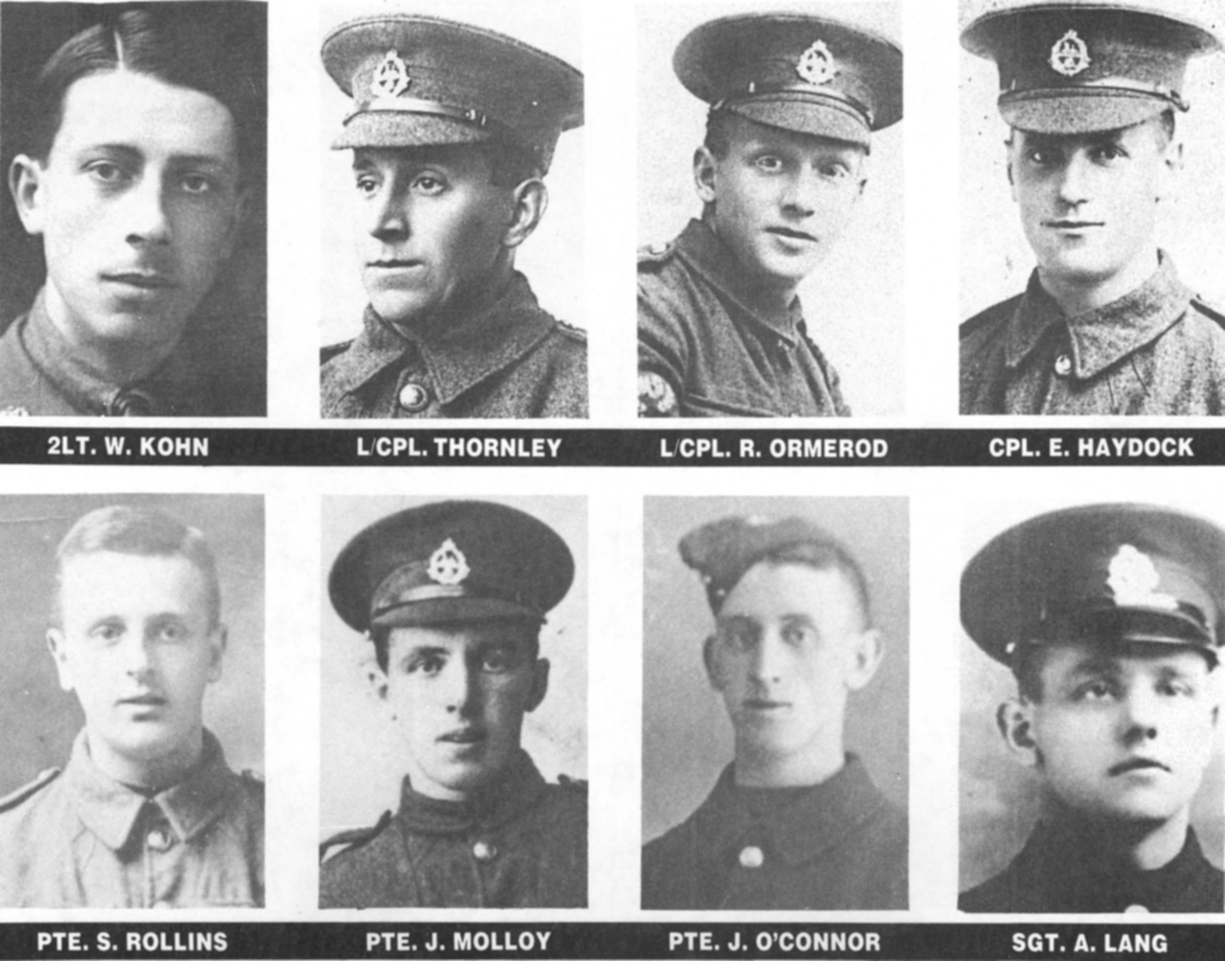

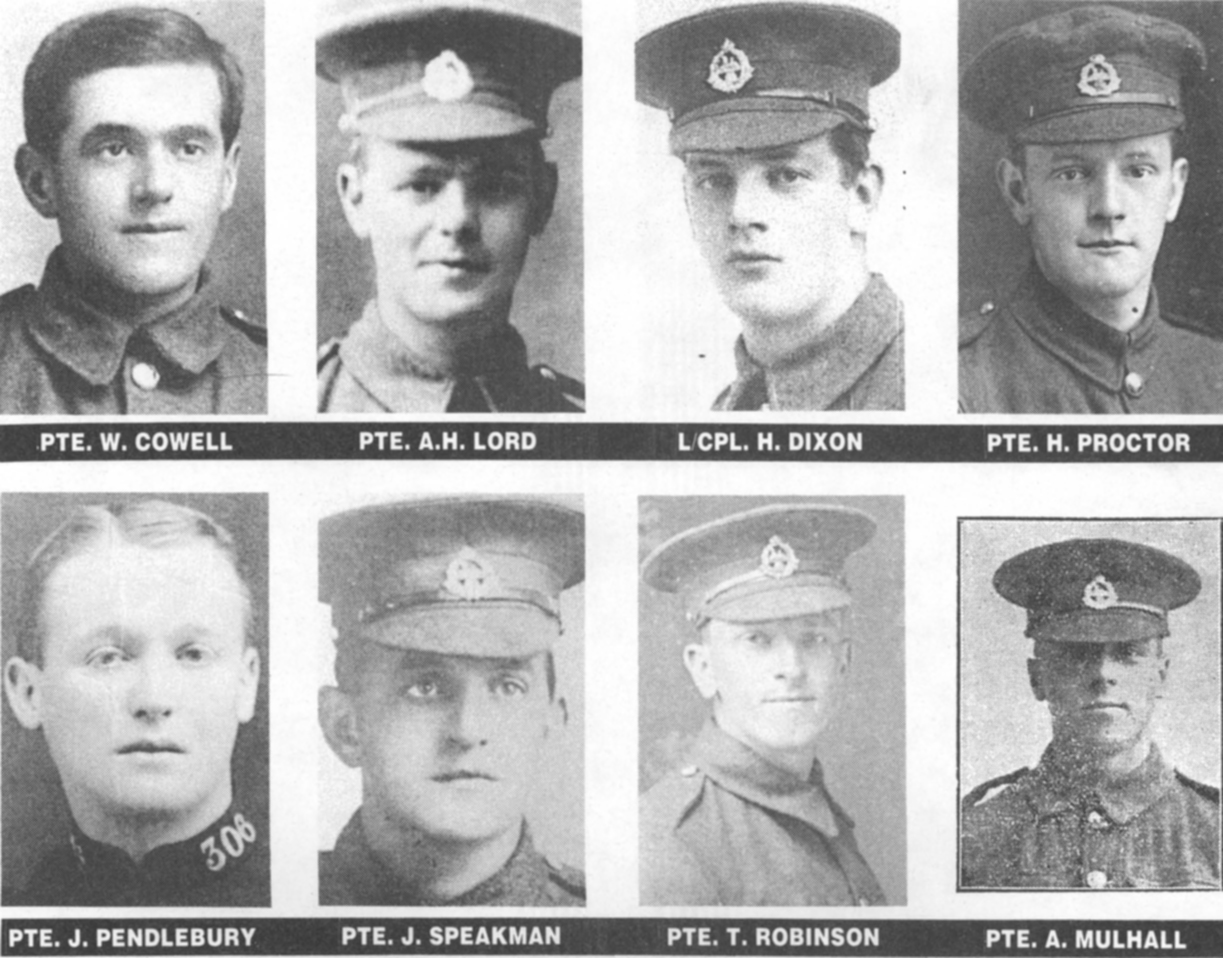

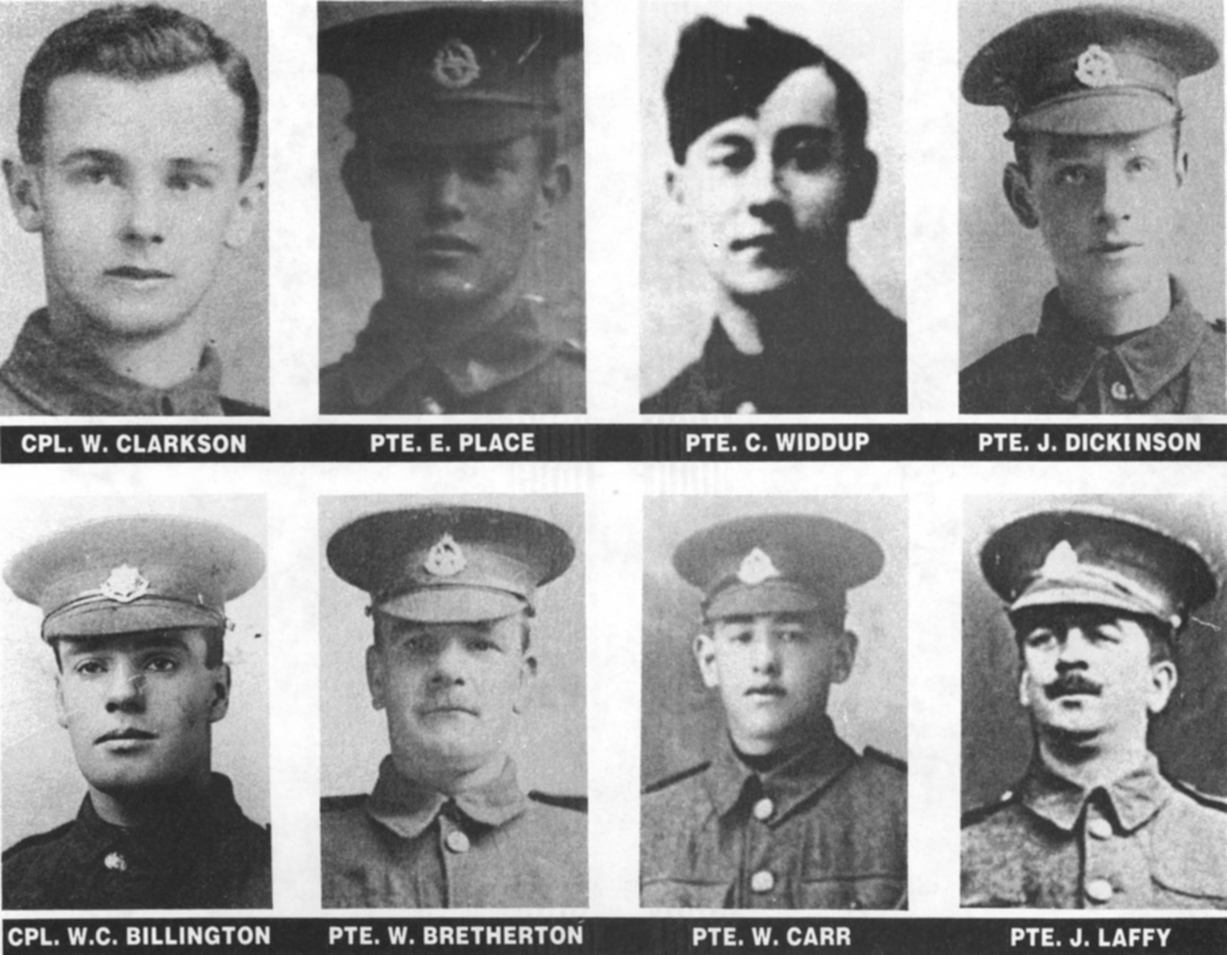

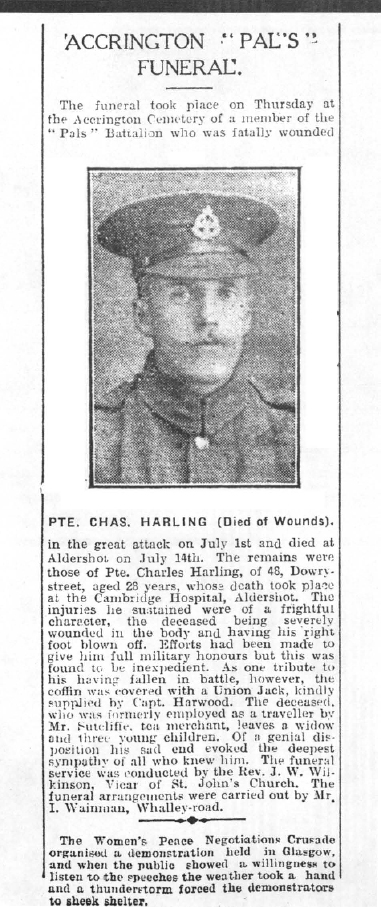

and on succeeding pages are shown 46 (20% or 1 in 5) of the 235 killed in action on July 1st, 1916. 135 (57%) of the total have no known grave.

“Six men were killed in our section of the trench before the whistle blew to go. My best friend, Pte. James Leaver, was killed by my side as we struggled out of the firing-step towards the gap in our wire. We found our wire had not been cut for us to get through.20 We couldn’t run because of the weight of our packs and men were going down like ninepins. By some miracle, I got to the German wire about ten yards in front of their trenches completely untouched. I then dropped to the ground. I looked round and saw not a soul moving, just dead and wounded. The Germans must have thought I was dead. Moments later a shell burst above me. I felt a pain and a piece of shrapnel was sticking out of my leg. It started bleeding. There was a German on top of the trench playing a machine-gun over my head. There was still nobody to be seen. Another shell burst and a piece of shrapnel went in my other leg. I couldn’t move and I could feel blood running from me. I must have gone unconscious because the next thing I remember was the sun sinking down over the horizon.” (L/Cpl. J. Snailham).

During the attack the Battalion signalling section had two main functions. Firstly, three signallers each were attached to the second and fourth waves. During the advance they were to ‘take out a wire’ from the signal office in Mark Copse to the respective objectives of the ‘bounds’ and prepare a forward report centre to maintain telephone communication with Battalion and Brigade H.Q. as, in theory, the advance progressed. A second group of signallers, ‘H.Q. group’, were to maintain the lines between Company H.Q’s in the forward trenches and Battalion H.Q. in ‘C’ Sap and the Brigade H.Q. in Observation Wood, on the rising ground some five hundred yards behind Matthew Copse. Unfortunately these lines were destroyed by shell-fire as early as 7.50 a.m. so consequently communication was by runner.

Cpl. Bradshaw and his friend L/Cpl. Harry Bury were in H.Q. group. They stood outside their shelter, next to Brigade H.Q. 500 yards behind the lines and looked down the slope into the ‘arena’ of the attack. “We were able to see our comrades (the Pals) move forward in an attempt to cross No Man’s Land only to be mown down like meadow grass. I felt sick at the sight of this carnage and remember weeping.”21

During the morning Cpl. Bradshaw and L/Cpl. Bury saw men moving from shell hole to shell hole in their attempts to return to the British front line. One who returned was a fellow signaller, Cpl. Harry Hale. Cpl. Hale, with Pt. Orrell Duerden and Pte. Bill Stuart was attached to the fourth wave.

“At zero hour we advanced a hundred yards when a shell burst a dozen or so yards from us. The force knocked me down. Orrell and Bill said Are you hit?’ I said, ‘No, I’m O.K.’ so we carried on. We could see the lads dropping all around, and we remarked it was marvellous we were being missed. We got to the German front line and I was hit in the hand by a bullet. Orrell and I got into the trench and he bandaged my hand. He then said, ‘Will you remove this piece of shrapnel from my head?’ This surprised me because it was the first he’d said about it. He must have got it from the shell which knocked me down. I took it out — it was only a small piece, and although near the temple he said it didn’t hurt. Anyway, he didn’t look any the worse for it. A shell came over and knocked the parapet in, burying two chaps and almost smothering us. Orrell and I decided it was rather unhealthy there so we had to part — he to go onward to keep communication going and me back to the dressing station, for my left arm was now useless. We shook hands and wished each other ‘good luck’.”

Cpl. Hale never saw Orrell Duerden again.22

It was a frustrating ninety minutes for Col. Rickman who could see no sign of his four waves, except for small groups of wounded. Then Sgt. Rigby, of ‘W’ Company returned to report seven of his platoon with Captain Livesey (and presumably Pte. Glover) had got into the German front line and held it for twenty minutes before running out of bombs. Later at 11.15 a.m., Pte. Glover returned to say the remains of the first, second and third waves had combined, under the command of Captain Livesey to attack the Germans in their own front line. Such reports from wounded men were to be the sole source of direct information for Col. Rickman. Months of meticulous planning to ensure good communication during the attack ended in a dreadful irony.

By a miracle, Pte. Bewsher returned to ‘C’ Sap unwounded. Carrying his Lewis gun, Pte. Bewsher had reached a German communication trench with the first wave.

“I was right in front of a machine-gun post I emptied a drum at a few Germans who were on the trench parapet They were throwing ‘potato-mashers’ (stick bombs) over my head — I’d got a bit too near. Some of them went back down the trench — I was surprised to see how wide it was — and I went after them. I got nearly to their second line. I looked around and there was only me there so I decided to go back. Still holding the Lewis gun I went back to a shell-hole about twenty yards into No Man’s Land. I waited there thinking the lads (the rest of the wave) would be coming. I suddenly saw some Germans coming back up their communication trench. I didn’t know whether they were picking up wounded or not, I didn’t wait to see. I fired at them and they vanished. I was sure they were going to counter-attack so I ran back to our own lines. I had some near squeaks. One bullet hit my water bottle. I felt the water on my leg and I thought it was blood. Another went through my haversack. It broke all my biscuits and hit a tin of bull-beef. A piece of shrapnel hit my Lewis gun. It bent the barrel and knocked the foresight clean off. I saw a dead Sheffield Pal with his Lewis gun alongside him. I threw mine down, picked his up and dropped into a shell-hole. Then Gerry came back and I had another go at them. I picked up my gun, then made for our front line. By a stroke of luck I’d got to ‘C’ Sap. Lt. Col. Rickman was there with Captain MacAlpine, the Signals officer. The Colonel said, ‘Was that you firing that gun out there?’ I said, ‘Yes, Sir, I thought they were going to attack, I didn’t know whether they were stretcher-bearers or infantry men, but I had a do at them.’ ‘That’s my lad’ — he said. Then he turned to Captain MacAlpine and said, ‘Take his name and number.’ I thought, ‘What the hell for?’ Having your name and number taken was always for a crime.”23

The original front line trench, now almost levelled to the ground by shell-fire, became untenable so the ‘line’ moved back to part of Excema and Rob Roy trenches. These were held by those remaining of two companies of the 13th York and Lancaster Regiment under Captain Gurney. They were originally brought forward to reinforce the 11th East Lancs but stopped on the orders of Brigadier Rees when it became obvious the attack had failed. With Lt. Rawcliffe’s Stokes mortars and some slightly wounded East Lancs, plus four East Lancs officers and forty other ranks hurriedly sent from Colincamps, they were, under intense German shell-fire, awaiting a possible counter-attack.

At least one German M.G., that commanded by Unteroffizier Spengler, fired from the German second trench over the heads of those embattled in the German first trench. This concentrated on the two companies of the 13th York and Lancaster Regiment held in the new British front line. “They paused only to fire, with great success, at small groups of English who were to be seen over the first (German) trench parapet. Their steel helmets were clearly recognisable.”24

Col. Rickman, after ensuring Pte. Bewsher was alright, sent him to join the defenders.

“I was just setting my stall up (preparing his Lewis gun position) when I was hit on the head. I didn’t know what hit me. Next I knew I woke up in the Advanced Dressing Station at Colincamps.”

Pte. Clark had a meeting with Col. Rickman of a remarkably different kind. With his three colleagues he had been guarding the advanced store of ammunition and iron-rations for six days — since June 24th. During the morning of July 1st, he left the store and met a sergeant who took him to Col. Rickman.

“I was very worried about what he would do to us. I didn’t know the half of it. He greeted me in a rage. ‘Where the hell have you been?’ ‘Do you know you’ve been posted as deserters?’ He then added, for good measure, ‘You could all be shot for cowardice!’ I soon learned C.S.M. Hey had got a ‘Blighty One’, and I realised the only person who could help us was gone. The Colonel’s final words were, ‘I’ll deal with you when this business is over!’ He then ordered us into the front line with the others. We reported to L/Cpl. Frank Bath. He stared at us in amazement. His first words were also, ‘Where the hell have you been?’ ‘You’re in real trouble!’ We knew that alright. With this in mind we stayed in the front line until we were relieved.”25

Throughout the assault and bombardment, Ptes. Sayer, Rountree and Pickering waited to issue the bomb reserves but nobody came.

“Suddenly a piece of shrapnel hit Joe Rountree on the leg. His clothing set alight, I knocked the shrapnel away and smothered the flames. I asked Pte. Pickering to go for the stretcher-bearers. I made Joe as comfortable as I could with splints made from box lids. He was in agonising pain, his leg smashed. A runner on his way to Brigade came into the dug-out He obviously knew me but I didn’t know him. ‘Hallo Fred, how’s things?’ he said. I told him, ‘It’s a wasted effort to come here to issue bombs, nobody wants them.’ He replied, ‘Bugger t’bombs, everybody’s gone — it’s been a wash out’ He told me as much as he knew. As he left I gave him a postcard for my sister. She later got the postcard so I knew he had made it to Brigade. Sometime later the stretcher-bearers came for Joe”. (Pte. Sayer)

By now it was almost mid-day. Although the British trenches — and their own front and second line — were under fire from German artillery, the machine-gun fire eased off. “There was nothing left for them to shoot at.” (L/Cpl. Snailham).

An area, once meadowland, approximately 700 yards by 300 yards was filled with some 2,000 dead and wounded of the 11th East Lancs, 12th York and Lancasters and the supporting companies of the 13th and 14th York and Lancasters. Hundreds of dead stretched from British parapets across to German parapets and beyond. In shell-holes with the dead, lay the ‘lucky’ wounded, who had managed to scramble in. Others, less ‘lucky’, lay in the open in the searing sun of a glorious sunny day. By some insane contrast, unknown to those who earlier had dreamed of cricket, it was pouring with rain throughout East Lancashire. ‘Accrington versus Rishton’ was rained off. Burnley scored one run in one over against Church before they too, were rained off.

As wounded men crawled and inched themselves painfully back to their own lines, some of their comrades, amazingly, continued their advance. Staff officers, acting as observers, and positioned on the rising ground behind the lines, at first sent optimistic — and completely erroneous — reports to VIII Corps H.Q. At one stage during the morning the whole of 31 Division was reported on the western edge of Serre and consolidating. By 2.45 in the afternoon this had been amended to — “It is believed there are still some men in Serre but the remainder are back in our front line.”26

In spite of months of intricate planning it was now obvious events were out of Division, Brigade, even Battalion control. There were no means of knowing what was happening, let alone exercising any measure of command. Information came only from returning wounded and, less reliably, from individual observers. The G.S.O. (Operations) later wrote “The striking thing was the gradual change in the outlook and in the information received. Very elaborate arrangements had been made to get information back. Reports at first were very rosy and it was not for some time that we realised something was amiss”.27

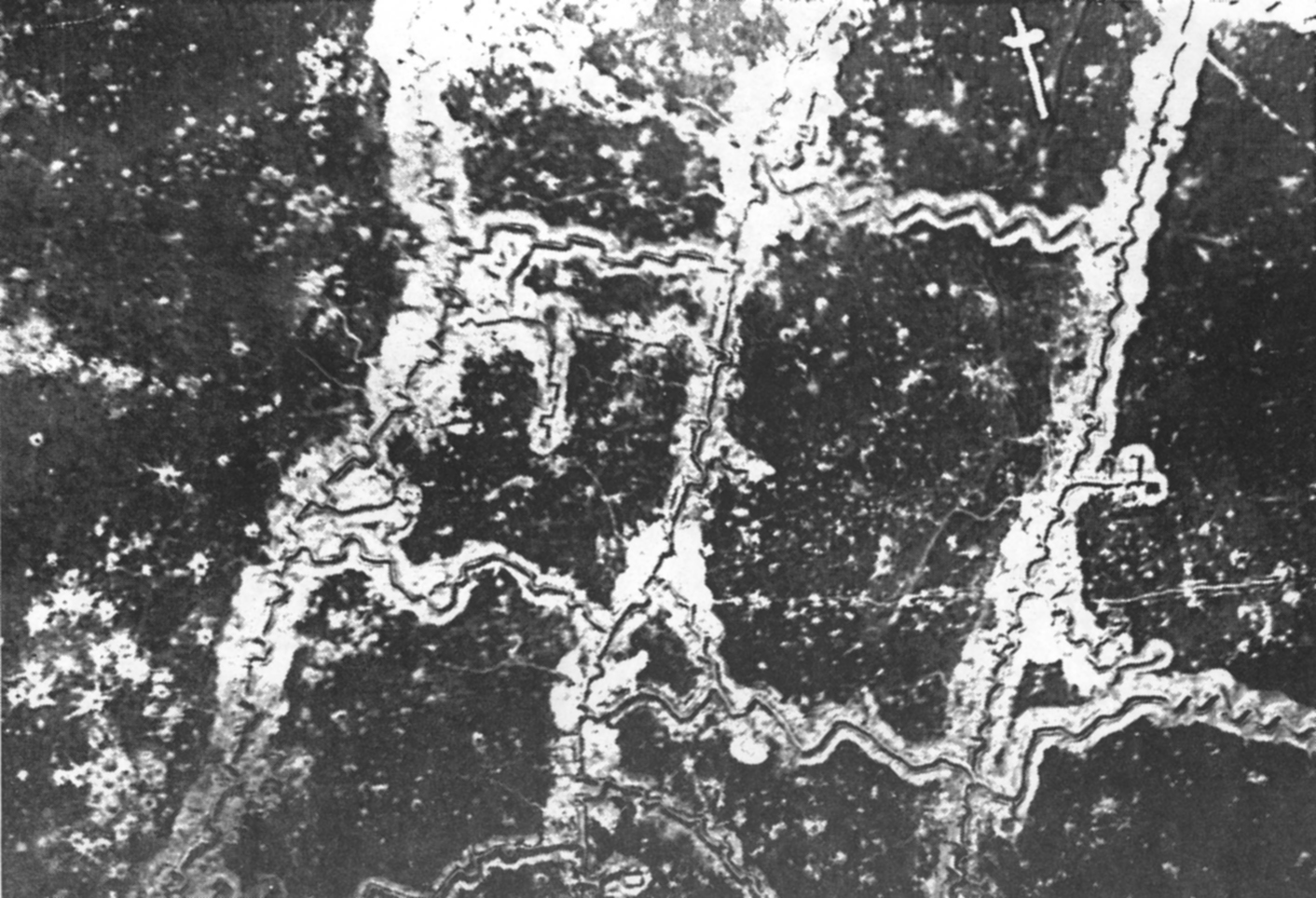

The killing ground. An aerial view of the German trenches attacked by the Accrington Pals. The first, second and third lines of trenches are clearly seen.

B.C.P.L.

By then it was too late. The attack had failed. Brigadier Rees realised this and so decided not to bring forward any reinforcements into the horrific enemy fire. Col. Rickman’s preoccupation was solely to get information from his wounded, to prepare as best as he could to defend his own front line and desperately get information to and from Division and Brigade H.Q.s.

Several observers saw isolated parties of 11th East Lancs men beyond the German front line, still following the rehearsed plan of attack. Brigadier Rees — “We could see these men from Brigade H.Q. when the smoke cleared. They were in a definite line and were probably all shot in the back from trenches they had crossed. An aeroplane later reported our troops in Serre, which I couldn’t believe.”28 Observers from the 18th Durham Light Infantry and the 15th West Yorks (93 Brigade) also saw men from 94 Brigade in the German trenches and in Serre village.29 92 Brigade reported about one hundred East Lancs just west of Serre.

As the gallant, encircled, men behind the German lines fought for their lives, every wounded man in No Man’s Land knew that all that was left of the plan of attack was for him to get back alive. So began a nightmare journey which would push some to the edge of their reason. The fatalism of the advance was now gone, in its place a desperation to survive. For those slightly wounded, who got back within hours, it was nightmare enough. For others who spent up to three days and nights in No Man’s Land it was a harrowing experience, the memory of which haunted them always.

“The shell blast must have knocked me unconscious. I don’t know how long I was out I had to get back although there was as much danger going back as forward. I could hear machine-gun fire all around. I was knocked over again by a shell burst. Another few yards and I got into one of our dug-outs. Someone put a piece of rag over my arm so I went forward into our trenches for it to be properly attended to. The trench was crowded with wounded so I crawled, best as I could, to another trench. That was as bad. It was unbelievable. Someone at the Regimental Aid Post innoculated me against lock-jaw but ignored my wounds. I couldn’t get near to get bandaged. I met Sgt. Ernie Kay. He was also wounded. He suggested we went back to Colincamps on our own. We walked and rested, walked and rested. Some Royal Artillery men gave us water, I remember, that was all we had. Somehow we got to the Advanced Dressing Station at Colincamps and I collapsed through loss of blood. I came round, outside, in a Geld. There were hundreds and hundreds out in the open. I asked a man where we slept. He said, ‘Here, with one blanket to five men, if you’re lucky’.” (L/Cpl. Marshall)

“I was blinded with blood. I started to roll back to our lines but my equipment prevented me. In spite of the machine-gun Bre, I knelt up, and God knows how, I threw off my equipment. Crawling, stumbling and rolling over our own barbed wire I reached our lines. I was dazed with loss of blood and someone, unknown to me, saved my life and bound my head up. What followed was a dream, I knew nothing until I was in hospital.” (Pte. Clarke).

“Suddenly, a shell burst near me and I was on the ground, with of all things, a plank of wood (probably from a dug-out) on top of me. That plank saved my life, I’m sure. Next I knew I was falling into our trenches. Things were so bad there I was left on my own to go to the Advanced Dressing Station for treatment.” (Pte. Fisher).

After getting a second chance, Pte. Anderson didn’t hesitate.

“I quickly made my way to another shell-hole. A wounded sergeant was in there. We daren’t move. Sniper fire was so accurate they could put a bullet through your hand with ease. The sergeant kept asking for a drink, but I had none to give him. I must have fainted, because the next I knew it was dark. The sergeant was dead. I was gasping for a drink and my leg was paining me. I knew I would have to make a move, so I started to creep back. The sky was lit up by shell bursts and Very lights. As I passed a shell-hole I heard a voice. Someone called my name and asked me to help him. I couldn’t, I was so weak I could barely crawl and I had no water. I never did know who it was, or whether he got back alive. I eventually got back to our trenches. A voice said, ‘Are you East Lancs? Your lot’s been wiped out’ An officer gave me a drink of water. Only then I realised my pack had been blown away, my rifle gone and every button on my tunic blown off. I was put in a dug-out and I laid on what I thought was a heap of sacks. They were dead men, piles of them. An order was given for anyyone who would walk to go down to the A.D.S. at Colincamps. I couldn’t stay where I was so went there best as I could. After treatment, open lorries took us down to the Casualty Clearing Station in the ‘Citadel’ in Doullens. This was crowded with thousands of wounded.” (Pte. Anderson).

“We laid in the shell-hole all night and the following day. Bill Bowers could see Lt. Stonehouse lying wounded a few yards away and went to see how he was. He got hit before he reached him. Later I thought, ‘Well, I’m going back’. I crawled out and passed Bill Bowers and Lt. Stonehouse. They were both dead. I took Lt. Stone-house’s revolver and put it in my pocket — I later lost it. I then managed to get to an old listening post and tried to get in. I couldn’t, it was so full of dead and wounded I couldn’t crawl over the top of them. As I got out I caught my tunic on our own barbed wire. I could hear bullets flying past as I struggled. Somehow I got loose and crawled to our line. I was just going to drop in when Frank Curran said, ‘Come on lad, I’ll give you a lift down’. It was quite a drop. I fell in, right on top of Harry Bloor, and onto the trench bottom where I could crawl into a dug-out. Tom Carey was laid out dead in there. It was full of dead and wounded mixed together. I tied my first aid pack round my leg. Later someone at Colincamps looked at my leg and shoulder. I was the luckiest man alive.” (Pte. Kay)30

Rigid in death. The body of a British soldier

B.C.P.L.

Lying two yards in front of the German wire, L/Cpl. Snailham knew he would have to move or die where he was.

“I unbuckled my equipment and pushed myself along, on my back, with my hands. I could hear their machine-guns all the time. I was getting near our line when I passed a shell-hole with three or four of the lads in. One shouted, ‘Watch out, there’s a sniper getting everybody who goes past there.’ I said, ‘I’m bleeding and I need treatment so I’ll have to get somewhere.’ So I chanced it and carried on. I was just get-ting through when he shot me through the top of my arm. I was lucky. I dropped into our trench and wandered about in a daze. The trench was empty. I was lucky again, ‘old’ Mather, ‘a general duty man’ now one of the Regimental Police, came towards me. (He was old to me, he was a family man, about forty, I was just turned eighteen). He said, ‘What’s up, Jimmy?’ I told him, and he half dragged, half carried me to the road leading to the Advanced Dressing Station at Colincamps. He left me there, with all the other wounded. An ambulance took me to the Citadel at Doullens (35 Casualty Clearing Station). When my turn came I was placed on a pig-trestle. One man held my arms, another my legs, while they took the shrapnel out of my leg. The bullet had gone right through my arm. Two days later I was on my way to Southampton.”

Some were not so lucky. Pte. Harry Fielding, of ‘Y’ Company and formerly the Blackburn Detachment, was wounded in the head and leg. Whilst crawling back, he was confronted by four Germans, who took him back to their lines as a prisoner of war. Pte. Fielding was one of only seven men of 94 Brigade taken prisoner that day. He spent the rest of the war in a P.O.W. camp in Nuremberg, Bavaria.

As L/Cpl. Snailham and the others lay at Doullens, Col. Rickman was en-route to hospital in London. At 9.40 p.m. on July 1st, after living through the anguish of seeing his Battalion all but destroyed, he was badly concussed and shell-shocked when a shell exploded nearby. Major Reiss became C.O. of what was left of the Battalion.

There were others not in the attacking companies who shared the horrors of July 1st and after. During the morning Cpl. Bradshaw and L/Cpl. Bury were ordered with others — transport drivers, sanitary men, general duty men, etc. — to help carry away the wounded and dead from what remained of the front-line trenches. The numbers of wounded had completely overwhelmed the Battalion medical services, in spite of an increase from 16 to 32 stretcher-bearers as part of the preparation. Many of the Regimental Band, traditionally stretcher-bearers in battle, were dead or wounded. Conditions in the front and assembly trenches were vile. Hundreds of wounded, mixed with the dead, were packed into half demolished trenches and dug-outs. Enemy shells were screaming everywhere at any signs of movement. The whole area was under constant German observation. Stretchers were almost useless because of the congestion.

“I vividly remember seeing two comrades carrying out on a stretcher a sergeant with his leg badly shattered. As I flattened myself to the trench side to allow them to pass, the sergeant said to the bearers, ‘If you keep jolting me I’ll bloody get off and walk.”(L/Cpl. Bury)

The German shelling lessened during the night of July 1st/2nd and Corporal Bradshaw and L/Cpl. Bury were able to snatch some sleep.

“We dug a hole in the trench side and hung a ground-sheet over the front We slept little and were out of the trench at dawn. On looking at Bradshaw, I recall saying, ‘Your eyes are sticking out of your head,’ to which he retorted, ‘And so are yours.’ We started immediately carrying out wounded and handing them over to the R.A.M.C.”31 (L/Cpl. Bury).

A wounded British soldier on the way to the rear and Blighty.

I.W.M. 721

On July 2nd, Pte. Sayer lay alone in the bomb-store, with neither food nor water.

“A Cyclist Company man dropped into the dug out He had been wounded in the attack and was now lost As he crouched with his back to me looking out towards the German lines I felt a blow on my helmet I choked with fumes and was blinded with blood and gore, I thought I was dead. A shell had exploded and shrapnel had pierced my helmet. The ‘Cyclist’ hadn’t moved — he was still looking forward. I crawled to him, then saw the lower part of his body was gone. It was his blood and gore, not mine.”

For four days and nights men laboured to bring wounded to the overburdened Regimental Aid Posts and the Advanced Dressing Station at Colincamps. From there men were taken on-ward by ambulance and lorry to the Main Dressing Stations at Bertrancourt and Louvencourt and the Casualty Clearing Stations (Nos. 11 and 35) at Doullens. For many it was then hospital in ‘Blighty.’ In the line, in Matthew and Mark Copses, rain on July 2nd, and a violent thunderstorm at mid-day on July 4th which flooded some trenches up to four feet deep, added to the wretchedness.

On the morning of July 1st, there began the worst 48 hours of Lt. Rawcliffe’s life. After the advance Lt. Rawcliffe and his Stokes mortar teams retired to Rob Roy Trench. They found it impossible to advance, as planned, when the infantry attack had failed. Only one Stokes mortar was able to fire, — and without much effect — at the enemy machine-guns enfilading on the Battalion’s left.

“We watched from behind the lines. We could see the men being simply slaugh-tered, then there seemed to be nobody there. The trench mortars never got a chance to help, our range was too limited. During the morning I decided to go down to the front line. I met a Staff Captain who said, ‘You can’t go down there, there’s been a wash-out’ I was so upset I said, ‘I’m not taking orders from you, sir,’ brushed past him, and carried on down. Things down there were unbelievable. Shells were continuously exploding all over the place. I came to a sergeant screaming and crying like a child, obviously shell-shocked. I was talking to him, trying to calm him, when a whizz-bang burst at our side. The blast caught my steel helmet under the rim, blew it back and the strap nearly choked me. I almost blacked out. When I got up the sergeant was nowhere to be seen. He had been blown to pieces. At nightfall I went into No Man’s Land, with my orderly and two volunteers, looking for wounded. We crept along and listened but didn’t hear a soul. Later, however, we helped about thirty into the trenches who had somehow dragged themselves back. That night I will never forget. We continued without rest into the following day.”

In a period of black horror there was just one incident which gave Lt. Rawcliffe some relief.

“I was making my way along a communication trench when I saw some feet sticking out from under a ground-sheet. I turned it over and thought ‘Poor old Gurney9 (Captain Gurney, 13th York and Lancasters) and prepared myself to move the ‘body.’ At this he woke up and ticked me off for disturbing the first rest he’d had in days. I was overjoyed to get that ticking off! I later came out of the line and went to Louvencourt. There, as one of the few officers unwounded, I got the job of going through the belongings of officers and men killed, in order to return personal belongings to their families. It was heart-breaking. I’d lost so many of my friends. My own brother-in-law Sgt. Harry Chapman was amongst them.”32

Major Ross came over from 31 Division H.Q. to help, presumably with the belongings of men from ‘Z’ Company, of which he had so long been the Company Commander. A fortnight later, Major Ross was in hospital in London, suffering a ‘break-down in health.’

Sometime in the afternoon of July 4th, Lt. Heys of ‘Z’ Company entered Pte. Sayer’s dugout. “Lt. Heys said, ‘Come on, we’re getting relieved shortly.’ I said, ‘I can’t walk because of my leg and back.’ He said, “You’ll have to, we can’t carry you. Go any time and any way you like, but get out of here.” ‘I still had no pass or written authority to travel alone but I didn’t need one this time.’ Long after darkness had fallen, and dead on his feet with pain and exhaustion, Pte. Sayer arrived at Colincamps.

“I fell in a heap and slept for ten hours. I awoke to find someone had removed my boots and equipment, bandaged my head and put me in a bunk.”

“I did get a laugh however when I saw the sausage was still on my haversack, quite undeterred by its adventures. I must say though, that was the worst birthday I ever had.”

On July 4th, 1916 Pte. Sayer was nineteen.

On the evening of July 4th, 144 Brigade of 48 Division took over the 94 Brigade section of the line. One company of the l/6th Gloucestershire Regiment relieved the 11th East Lancs. at 12.30 a.m. on July 5th. As the weary East Lancs., with spirits at their lowest ebb, came out of the line, the incoming Gloucesters watched in respectful silence. They were seeing men pushed to the limits of their endurance. After four days the East Lancs, were leaving many of their dead in No Man’s Land and in the forward trenches. The men made their way as best they could, asleep on their feet, to Colin-camps for assembly and roll-call. Even there the agony continued. As ‘Z’ Company assembled for roll-call a shell burst nearby and killed 18496 Pte. Wilkinson outright. This left 42 to answer the roll-call. From Colincamps they continued, through Courcelles, Bertrancourt and Bus les Artois, the five mile march to Louvencourt and Warnimont Wood.

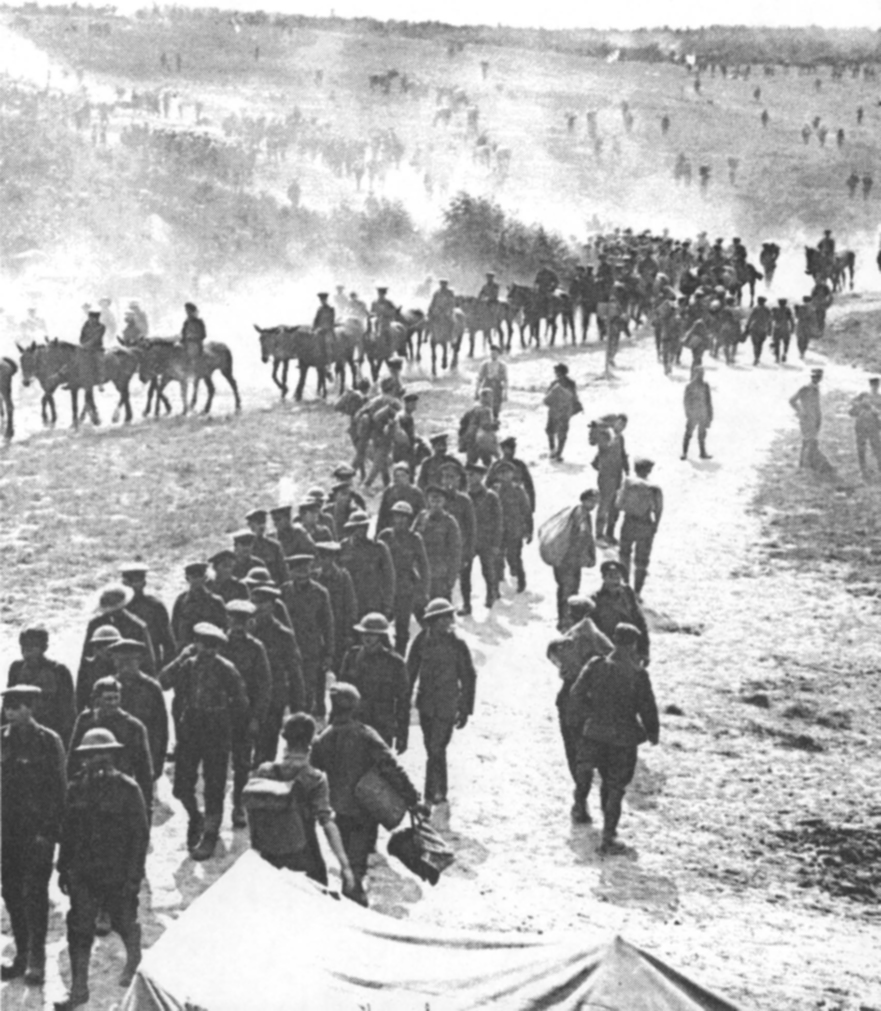

British prisoners of war are marched to the German rear.

B.C.P.L.

“When I heard they were back, I got out of bed and went down to the end of the lane and found them. I spoke to Charlie Birtwell and two or three others but I never asked them about the attack, there were so few of them. Frank Bath was coming down the road. He managed to say, ‘George, Ernie’s gone.9930 (Pte. Pollard).

Of Pte. Pollard’s close friends and comrades only L/Cpl. Bath was unscathed. Ptes. Bowers, Carey, Stuttard and Place, and Cpl. Smith were dead. Apart from Pte. Birtwell (wounded on the left cheek), Ptes. Greaves, Kay and Wilkinson, and Sgt. Pilkington, were lying wounded in hospitals scattered throughout the United Kingdom.

The end came for Pte. Pollard.

“I was stretchered, taken by lorry to the hospital train and then to Etaples. Later via Boulogne I sailed to Folkestone. Four hospital trains awaited us. Orderlies came round. ‘Where you from, chum?9 I said, ‘North of England.9 I finished up at Keighley. The hospital was in the old workhouse. We were the Grst troops in.”31

Pte. Pollard

In a letter intended for his mother’s peace of mind, L/Cpl. Marshall later wrote from hospital in Liverpool. ‘— my wounds are only of a slight nature. Arthur (Brunskill) was still going on when I got hit. I can only hope he is alright and has got through. Ben (Ingham) was badly hit before we went over and I do not know how he is going on as yet. I have been a very lucky chap. I hope Arthur will be as lucky. As you know we were the best of chums. I need hardly say what it was like — but if hell is like a battle-field, then God help the sinner.’35

Despite the desperate valour of those who fought and bombed their way along the first, second and even third German trenches, the German troops at all times kept their nerve. They fought with great courage with their leaders always in control. The battle-report of their No. 1 Machine Gun Company summed up their feelings, ‘With great sacrifices but with great bravery a complete victory was achieved.’ To achieve victory, 169 Infantry Regiment used 74,000 rounds of M. G. and rifle ammunition, and over a thousand hand grenades. The Regiment lost 81 officers and men killed, 151 wounded and 10 missing.

German positions in Serre obliterated by shell-fire. A picture taken by a British photographer in February 1917.

I.W.M. Q1812

Not only did Pte. Sayer see a verbal play on the name ‘Serre.’ The writer of the battle-report of No. 7 Company, 169 Regiment (opposite 93 Brigade) could not resist ending his entry for 1st July 1916 with the pun, ‘SEHR HABEN SIE GEKRIEGT ABER NICHT SERRE!’ — ‘They had much but they did not have Serre!’

234 of the 11th East Lancs died before Serre. 131 of these have no known grave. At least 360 men were wounded. Fourteen died in hospital within a month. Numbers unknown died directly and in-directly of their wounds in future months and years. With Captain Riley died ten of his Lads Club members. Another died of wounds on July 9th. With their comrades, died 15259 Sgt. Walter Todd, who tried so hard at Malta to rejoin his Battalion, and 17882 Cpl. Joe Bell, who served with Rickman in South Africa; 15644 Pte. Will Cowell, also died, he who had so longed for leave to see Polly. Their bodies were never identified.36

Some of the officers wounded on July 1st, 1916.

Capt. B. Endean

Capt. A. Peltzer For many wounded the ordeal ended in a hospital in England. After treatment some returned to the Battalion. Others were transferred to other Battalions of the East Lancashire Regiment or to other regiments to serve again in the trenches on the Western Front.

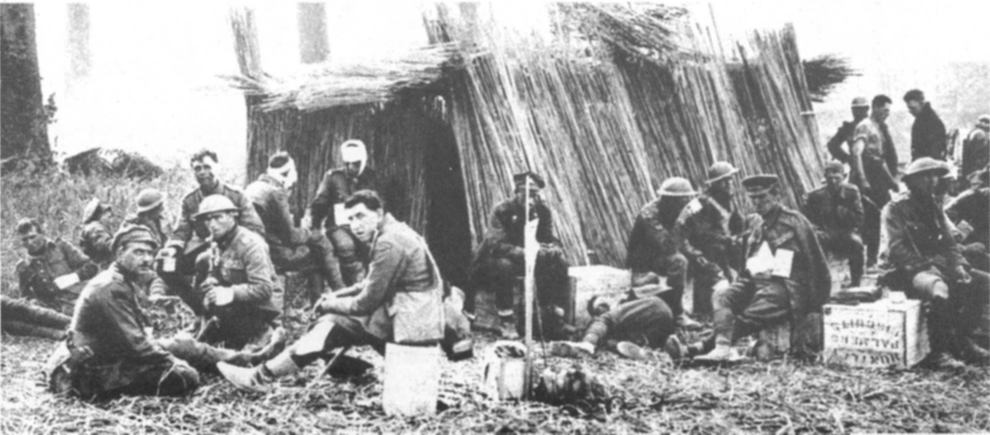

Their wounds now dressed, British troops await transport to the rear.

B.C.P.L.

1. See ‘The York and Lancaster Regiment’, Volume 2, p 235. Col. H.C.Wylly,1930.

2. In the haversack were small things, mess tin, towel, shaving kit, extra socks, message book, the unconsumed portion of the days ration, extra cheese, one preserved ration and one iron ration’. See Military Operations, France and Belgium 1916, p 313.

3. Operational Orders 94 Brigade 26/6/16 para 5, ‘Bombs’.

4. A.O.T. 22/7/16.

5. See Brigadier H. C. Rees Papers (77/179/1) Imperial War Museum.

6. 11th East Lancs War Diary WO 95/2366 Public Record Office.

7. See ‘History of the East Lancashire Regiment in the Great War 1914–1918’ p 526.

N.B. Subsequent material, and eye-witness descriptions, show Captain Tough, not Captain Livesey led the first wave.

8. Some tapes were seen before daylight. ‘A’ Company of the 12th York and Lancaster Regiment, on the 11th East Lancs immediate left, reported at 4 a.m. that there was no sign of the white tape which was laid during the night. “It had apparently been removed. It served no purpose at all except to give the enemy warning. The wire in front of our own lines had been cut away too much and as the gaps were not staggered our intention to attack must have been quite obvious”. (Battle Report, 12th York and Lancaster Regiment).

9. Troops will take up positions in the trenches during the night prior to the attack. Absolute silence will be maintained. No smoking will be permitted and great care will be taken that bayonets are not shown above the parapet prior to the advance’. Operational Orders 94 Brigade 26/6/16 para 8, ‘Assembly’.

10. The Lancashire League formed in 1890 had clubs representing Accrington, Bacup, Burnley, Church, Colne, Enfield (Clayton-le-Moors), East Lancs (Blackburn), Haslingden, Lowerhouse, Nelson, Ramsbottom, Rawtenstall, Rishton and Todmorden. Of these only two, Ramsbottom and Todmorden, were outside the Battalion recruiting area. Many supporters and ex-players served in the Battalion, e.g. Lt. Rawcliffe’s brother-in-law Lt. Ramsbottom had been captain of Accrington in 1914. Lt. Rawcliffe’s orderly was ex-wicket keeper for Enfield.

11. Often the first intimation to the family was not the War Office telegram but a letter from a comrade. Pte. Shorrock wrote to Mrs. Coady in Oswaldtwistle. “I am sorry to tell you your son Tom is killed. All the boys are down about losing him. He was a good soldier, always in for a bit of life and cheering the others up. He was my best pal. We went everywhere like brothers. We all send our deepest sympathy”. (A.O.T. 18/7/16).

12. A.O.T. 15/7/16 15193 Pte. William Clarke was wounded on July 1st and was in hospital in Sheffield.

13. ‘C’ Sap, one of four ‘Russian Saps’ i.e. shallow tunnels, like small mine galleries. Previously excavated by the ex-miners of the 14th York and Lancaster Regiment, ‘C’ Sap ran at a right-angle from the front line trench into No Man’s Land. It had been intended for the leading waves to enter No Man’s Land but it had been badly blown in by enemy shell-fire. (This caused the last minute change of plan which meant Lt. Col. Rickman’s delay on arrival).

14. B.E 19/8/16 15184 Pte. J. Roberts was wounded on July 1st and was in hospital in Kent.

15. B.E 29/7/16 Letter to Pte. Tyson’s father. Sgt. E. D. Kay was wounded in the arm, back and shoulder on July 1st.

16. Opposite 94 Brigade were the troops of 169 (8th Baden) Regiment from the province of Wurttemberg/Baden. To their right, in an enfilading position, were troops of 66 (3rd Magdeburg) Regiment from the province of Saxony. Both regiments were in 52 Division.

17. Baden Generallandarchiv Karlsruhe 456 EV 42 Bd 115 (hereafter B.G.K.).

18. A.G. 15/7/16 15013 Pte. Glover, with three wounds on July 1st, entered hospital in Radcliffe, Manchester, on July 8th.

19. Quoted in ‘Heroic deeds of members of 6 Company, Infantry Regiment 169, in the Battles of the Somme 1916’. B.G.K. 456 EV 42 Bd 127.

20. At 6.20 a.m. 94 Brigade H.Q. assured G.H.Q. the wire had been ‘perfectly’ cut.

21. See ‘The First Day on the Somme’, Martin Middlebrook pp 150/151.

22. A.G. 8/8/16 Letter to Mrs. Duerden in response to her newspaper advert asking for news of her son. 15463 Cpl. Hale was in hospital in Cheshire. Pte. Stuart wrote from France saying he would enquire about Pte. Duerden’s whereabouts. He was unsuccessful. 17870 Pte. Orrell Taylor Duerden’s body was never found. His name (incorrectly as C. T. Duerden) was placed on a supplementary panel on Thiepval Memorial in 1933. For the rest of her life his mother refused to believe he was dead.

23. 18048 Pte. S. Bewsher was awarded the M.M. for his coolness and bravery.

24. B.G.K. 456 EV 42 Bd 115.

25. 17859 Pte. S. Clarke, served with the Battalion, with Lt. Col. Rickman as O.C. until March 1919. The matter of his absence was never ‘dealt with’ and Pte. Clarke was content for it to remain so.

26. See VIII Corps Reports to General Staff H.Q. 1/7/16–3/7/16 P.R.O.

27. C.A.B. 45/188 P.R.O.

28. C.A.B. 45/190 P.R.O.

29. C.A.B. 45/188 (D.L.I.) and C.A.B. 45/190 (W. Yorks) P.R.O.

30. For reference to Pte. Bloor’s experiences, see ‘The First Day on the Somme’ p 248.

31. Quoted by kind permission of Mr. Martin Middlebrook.

32. Lt. T. W. Rawcliffe was awarded the M.C. for his conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty.

33. 15261 Pte. W. Greaves in hospital in Cosham, Hampshire with ankle, head and leg injuries wrote to Pte. Place’s mother. “The last time I saw him was in the front line, just before I got hit. I enquired about him as I got my wounds dressed and a stretcher-bearer told me he was dead. I am more than sorry. He was a good lad and a good soldier”. (A.O.T. 29/7/16).

34. 15139 Pte. G. Pollard was claimed out of the Army, as under age, by his father. He continued his engineering apprenticeship in munitions work in Accrington and Woolwich Arsenal, then joined the R.F.C. He served in France as armourer to Major Bill McCudden V.C. He left the R.F.C. in 1919.

35. B.E. 25/8/16. A later letter to L/Cpl. Marshall from Captain Heys of ‘Z’ Company, told him Pte. Brunskill’s body had been found.

36. By an oversight, discovered during research for this book, the names of 15644 Pte. W. Cowell, 15476 Pte. T. E. Francis and 15964 Pte. S. Rollins were not placed on the Thiepval Memorial. The author is grateful to the C.W.G.C. for their amendments to the Memorial and the Register.