Chapter Eight

The aftermath

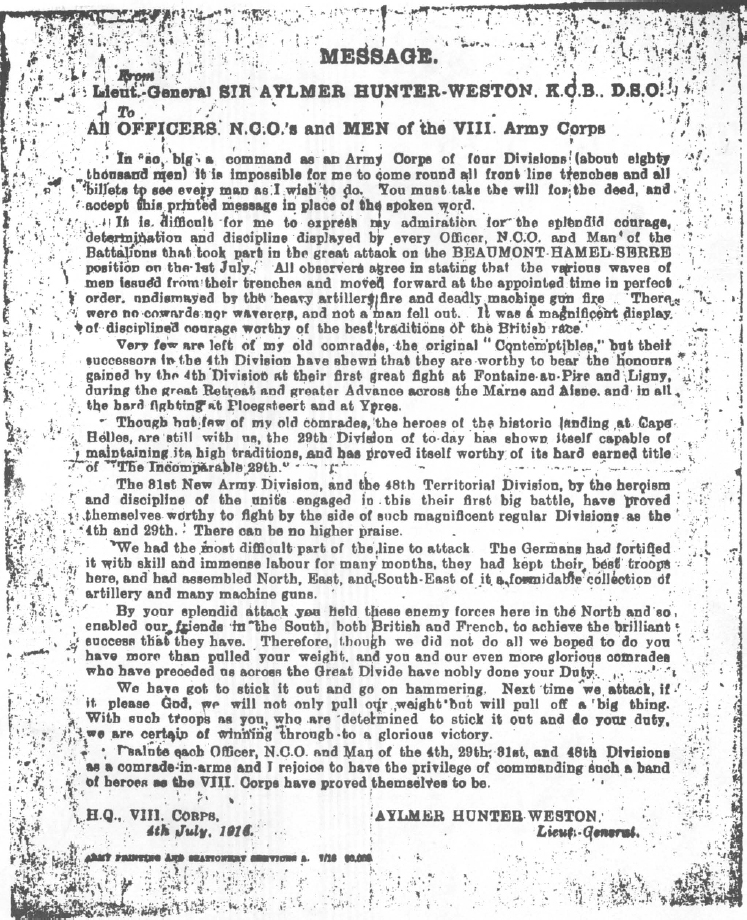

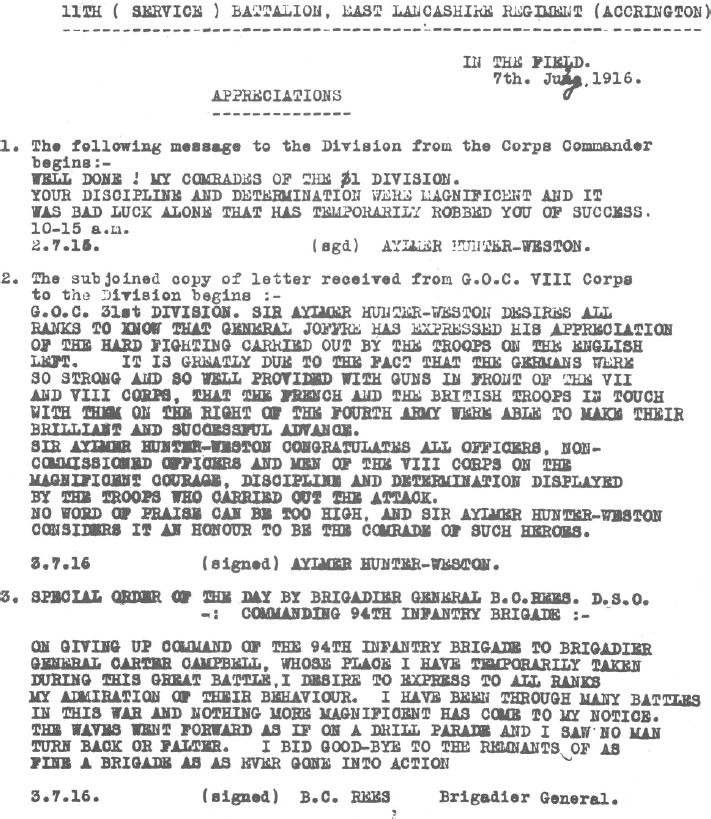

At Louvencourt laudatory messages from Hunter-Weston and Rees awaited the survivors. The compliments provoked a cynical reaction from the exhausted men. Hunter-Weston’s pre-battle assurances, ‘there would not be a rat alive in the German trenches,’ now had a hollow ring. Just over 400 men of the 11th East Lancs gathered at Louvencourt after the battle. Of these about 135 were survivors of the fighting platoons, the remaining 265 or so were men of Battalion and Company H.Q. administration and clerical sections (e.g. transport, stores, sanitary, etc.), stretcher-bearers and reserves who had succoured wounded and buried dead in the days after the attack (all but one of the medical staff and stretcher-bearers were casualties). At Louvencourt the burnt-out survivors rested for the first time in six days, the nightmare over.

Whatever the reasons for the failure of the attack — poor planning, bad tactics, staff incompetence, over-confidence of the British High Command, quality of the German defence — those remaining of the 11th East Lancs slept knowing none could have bettered their efforts in the attack.

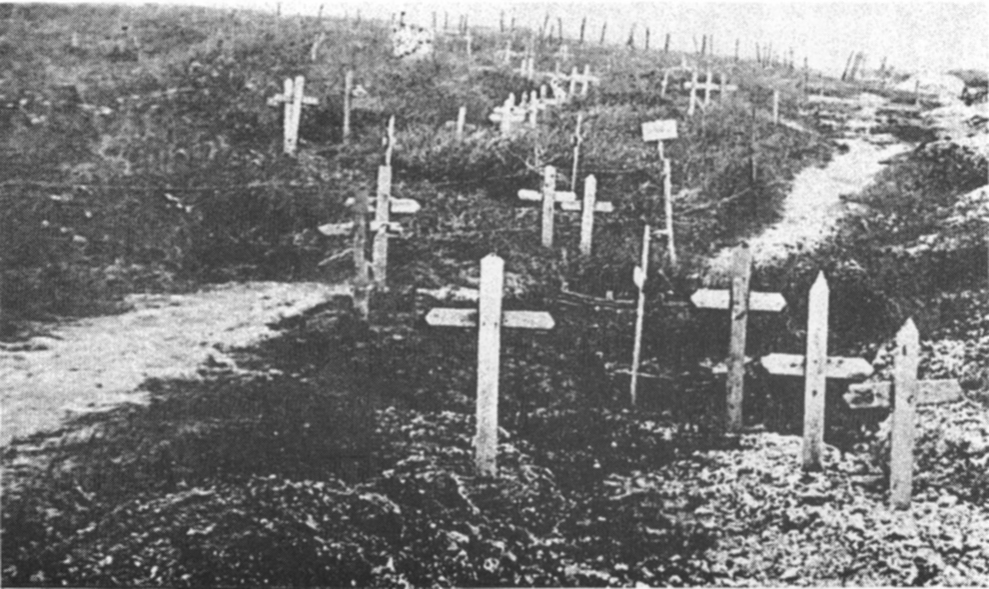

After the battle, temporary wooden crosses for men buried where they fell.

B.C.P.L.

Several interlinked reasons caused the tragedy on the slopes before Serre. In common with the rest of the British front the seven day bombardment by British artillery proved for the most part ineffective against the German trench system. Contrary to High Command belief, shrapnel shells failed to completely cut the wire. Many H.E. shells failed to explode. In the relative comfort of twelve-feet deep dug-outs the Germans endured the shelling of the heavy guns. After five days the decrease in intensity of the bombardment convinced them the worst was over. When the bombardment suddenly ceased on the seventh day, an imminent attack was obvious. Within minutes, as the British troops were leaving their front-line positions, the Germans with great skill and gallantry brought their machine-guns up from the deep dug-outs and opened fire on the advancing waves.

The pace and spacing of the four waves provided perfect targets. Succeeding waves continued their slow, remorseless advance to be cut down with the machine gunners having ample time to fire at each wave before the next took its place.1 The troops who got as far as the German lines were stopped (as L/Cpl. Snailham was) by unbroken wire up to five feet high. Had this been cut, those who survived the initial advance might possibly have dealt with the machine gunners.

This was not to be as the survivors were too few, mostly wounded and perforce sheltering in shell-holes (one of the ‘blessings’ of the artillery bombardment). Of the wounded survivors only Pte. Clarke and Pte. Bewsher record firing a shot. The Battalion bombers and Lewis gunners were too few and too short of ammunition, the trench-mortars, unable to advance, were out of range. Those who were left could neither see nor reach the enemy machine-gun emplace-ments. However Cpl. Earl Whittaker of ‘Z’ Company, on his return, swore he saw a German machine-gunner in his shirt-sleeves.

Although much can be said in hindsight, the importance of Stokes mortars in the attack was over-rated. The stocks of bulky shells took up an enormous amount of room in trench and sap. Putting them there consumed precious time and energy. The general belief in their effectiveness was probably based on a demonstration behind the lines, on June 8th, for the Brigadier and his staff. 94/1 and 94/2 Trench Mortar Batteries fired a hundred shells at a line of trench and barbed wire. The wire ‘was well-cut’ and ‘much damage’ done to the trench.2 This ‘success’ undoubtedly gave Brigade staff confidence in Stokes mortars as support for the unopposed advance they anticipated. Those staff officers who proposed more machine-guns instead were brushed aside. These men believed machine-guns firing over the advancing waves would keep German heads down the moment the artillery bombardment ceased, so enabling the waves to overcome the front line trenches. In the event, the Stokes mortars, after their hurricane bombardment at 7.20 a.m. could not later help the attacking infantry because of the hold-ups in No Man’s Land and at the German wire. Also — ironically — the heavy German machine gun fire raining on the British front and support trenches.

The battle plan itself, however, became a major cause of failure. The over elaborate plans drawn up so carefully to cover every contingency were rendered useless by the over-looked contingency of the enemy contesting the ‘walk’ across No Man’s Land. The elaborate plans, much too cut and dried and inflexible, meant the 11th East Lancs. along with their comrades in the York and Lancaster Regiment lost the battle before it started. From zero hour Rick-man remained powerless and impotent with no communications to Brigade, Division or Corps. With his signals wire destroyed and his signallers in the waves dead or wounded, he lost control over the attack. The momentum and conduct of the attack remained in the hands of small, isolated, groups led in many cases by N.C.O.s or men. (C.S.M. Leeming, with all his officers killed or wounded, continued to lead a ‘Z’ Company wave into the attack. He received the D.C.M.).

Few of 94 Brigade were taken prisoner on July 1st, 1916. those who were would spend the rest of the war in the desolate confines of a German prisoner of war camp, such as this at Zwickau, Saxony.

Brigade also lost control. Brigade H.Q., a steel shelter ten feet underground in Observation Wood, lay 500 yards behind the line. On July 4th, Rees could only say — “From bits of information and from what the intelligence officer saw, it appears some of the East Lancs. got into Serre. He is very positive about this — also that after they entered the village the Germans shelled half way up the village, lifting off our front line. Two men of the 11th who saw this also bear it out, one was in the third line —.”3

When the survivors of the attack on the village of Serre arrived at Louvencourt they found these messages affixed to the Battalion notice board.

The courageous attempts of the 11th East Lancs. and the 12th York and Lancasters of 94 Brigade to continue the attack — which may have taken some into Serre village — were not brave ‘forlorn hopes’, but the actions of men who believed the success of others depended on them. The rigid instructions which left nothing to individual discretion were followed to the death. Only men wounded and alone turned back, their obligation to go on at an end, thus saving their lives. Those wounded and unable to return lingered for up to three days, isolated and in agony from wounds and thirst, until they died.4

Many varied reasons for the failure, all interlinked, can be put forward. The absence of an effective counter-battery attack by the British Artillery enabled the German guns to fire an intense and accurate counter-bombardment until 2 a.m. on July 2nd, causing many casual-ties.5 The 11th East Lancs orders meant a pre-battle seven mile, ten hour journey, each man carrying a load half his own weight. Men collapsed exhausted in their attack positions only three hours before zero hour. In spite of the training sessions, inexperienced men were used. Some of the 11th East Lancs men — replacements for the May and June casualties — were raw conscripts, who only nine weeks before were clerks and shop assistants in Blackburn or Burnley. Nineteen such men died in action on July 1st.

Similarly the untrained 31 Division Cyclists transferred to fighting companies in May. Of these, eight men from the East Yorkshire Regiment and Hull died. Also, whatever tactical and logistical difficulties the Battalion overcame, the complex wheeling manoeuvre to be carried out as they advanced would not be an easy exercise for a battalion in training, let alone in the battleground conditions before Serre.6

In Rees’ opinion the time for the manoeuvre was also too short. Rees had a severe argument with Hunter-Weston before he induced him to allow an extra ten minutes for the capture of an orchard 300 yards beyond Serre. “In twenty minutes I had to capture the first four lines of trenches in front of Serre. After a check of twenty minutes I was allowed forty minutes to capture Serre and twenty minutes later to capture an orchard on a knoll 300 yards beyond.” He added, “My criticisms on these points are not a case of being wise after the event. I did not like them at the time but I do not profess to have foreseen the result should a failure occur. A great spirit of optimism prevailed in all quarters.”7

An officer much closer to the men than Hunter-Weston and Rees also praised the men in their defeat. 94 Brigade’s Brigade Major F. S. G. Piggott, later wrote, “The New Army 31st Division was no whit behind the Regular 4th and 29th Divisions in gallantry, determination and efficiency.” Speaking of 94 Brigade on July 1st he went on, “In spite of its failure, it was a very remarkable feat of arms by the temporary soldiers of Accrington, Barnsley and Sheffield.”8

British wounded sent to ‘Blighty’ sometimes went to small hospitals run by the British Red Cross Society or the St. John’s Ambulance Brigade. The photograph shows a group in a St. John’s Ambulance hospital in Elmfield Hall, Accrington. Many of the nurses and staff were related to Pals’ officers and men. As far as is known, however, none of the Pals wounded on July 1st, 1916 were lucky enough to arrive here.

L.L.H.D.

Lt. General Sir Aylmer G. Hunter-Weston, D.S.O. Commander of VIII Corps.

I.W.M.

At G.H.Q. Haig knew nothing of individual battalions and saw matters differently. His earlier judgements about the effectiveness of VIII Corps were unchanged. VIII Corps, on July 1st, lost 662 officers and 13,363 men, but Haig still noted in his Diary — “few of VIII Corps left their trenches.”9 Such a view surely could only rest on the fragmentary reports of the observers. In fairness to Haig he later, in a despatch written on December 23rd, 1916, spoke of “striking progress made at many points” north of the River Ancre (VIII Corps sector) and of parties of troops penetrating enemy positions at, amongst other places, Pendant Copse (4 Division) and Serre (31 Division).10 He referred also, in his diary for July 1st, 1916, to “two battalions which occupied Serre village and were, it is said, cut off.”11

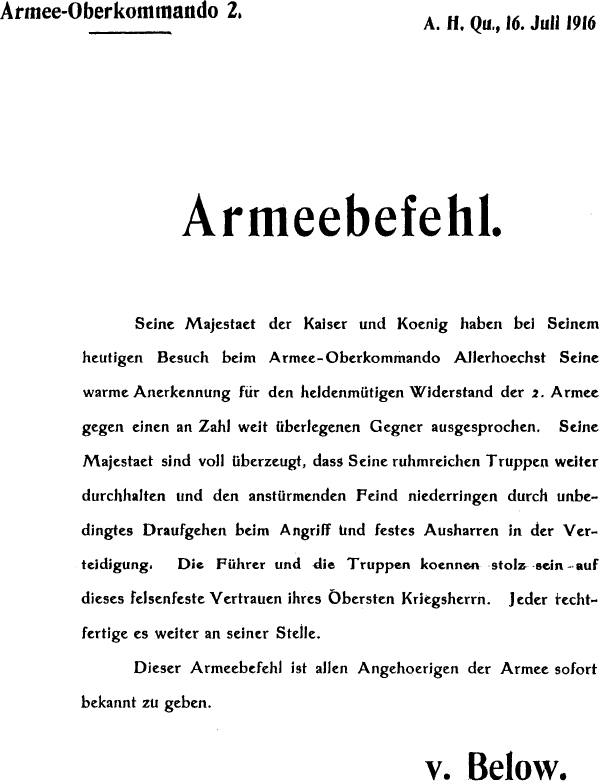

ARMY ORDER

His Majesty the Emperor and King has expressed at his visit today to the Army High Command his warm appreciation of the heroic resistance of the 2nd Army of an opponent by far superior in number. His Majesty is fully confident that his glorious troops will continue to hold out and resist successfully against the enemy’s persistent attacking, remaining steadfast in defence. The commanders and troops can be proud of the unshakeable confidence of their Supreme Commander.

This Army Order is to be issued immediately to all members of the Army.

As early as 7 p.m. on July 1st, Rawlinson, Commander of the 4th Army, agreed with Haig to transfer VIII Corps, with X Corps, to Lt. Gen. Sir Hubert Gough’s Reserve Army on the morrow. Haig’s comment being, “The VIII Corps seem to need looking after.”12 This criticism, directed more against Hunter-Weston, whom Haig disliked personally and wanted out of the way, again reflected on the officers and men of VIII Corps. Gough, though disappointed at the turn of events, reacted more favourably towards VIII Corps. “In one day my thoughts and ideas had to move from consideration of a victorious pursuit to those of the rehabilitation of the shattered wing of an army.”13

In East Lancashire, with the rest of the country, the long anxious wait for the ‘Great Offensive’ with its Victorious pursuit’ was ended. At first the news was optimistic. ‘The Times’ on Monday, July 3rd, gave unofficial news (from a German source) of the capture of Serre and La Boiselle with heavy losses. In Burnley on July 5th, the day of Pte. Wilkinson’s death in Colincamps, the Burnley News, not knowing the offensive had already ground to a halt, spoke of the magnificent start made and of British troops steadily making headway.14 However, by Saturday, July 9th, the story radically changed. Although the East Lancashire newspapers published the official, censored reports which gave an optimistic view of events, their editors could not contain a growing anxiety. They knew a stream of letters from the East Lancashire Records Office at Preston had been arriving in local homes since Wednesday. Earlier in the week a train full of wounded stopped outside Accrington station. A voice shouted to a group of women,

“Where are we?”

“Accrington!”

“Accrington? The Accrington Pals! They’ve been wiped out!” The news quickly spread, adding to the tension.15 Rumour now abounded and scores of people called at the newspaper offices every day asking for news. Something was ‘up’.

By the end of the week, wives and mothers whose regular flow of letters from France had dried up, visited friends and neighbours for news of others in the Battalion. Letters of assurance from wounded men in hospital in England were already arriving for some families. The numbers of these alone were enough to feed the rumours that the unthinkable had happened. Pte. Glover, placed in No. 2 Western Hospital, Manchester, by Wednesday July 5th, received a visit from his father on July 7th. He brought back Pte. Glover’s story for publication in the Accrington Observer and Times.

The difference between official news stories and the reality in their home towns at first forced newspaper comment to be equivocal. The Accrington Observer declared, “What is certain is the Pals Battalion has won for itself a glorious page in the record of dauntless courage and imperishable valour — the dead and wounded are more numerous than we would fain have hoped.” In an attempt to allay fears, it continued, “In the case of the wounded it is consoling to know the injuries are comparatively slight.”16

Other editions tried to say one thing and mean another. “The Chorley Pals have suffered considerable losses in the offensive. So far none have been officially reported killed. In the majority of cases the men are wounded, many only slightly.” It added, with more candour, “We fear next week the casualty list will be augmented, for the attack was of such a nature one cannot possibly think otherwise.”17

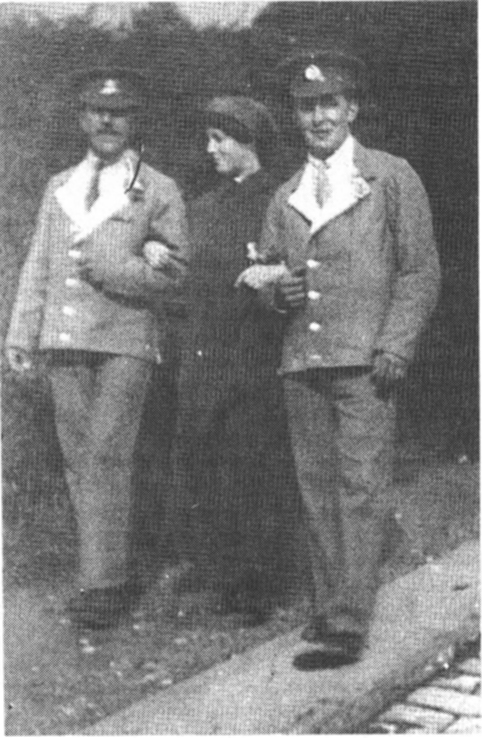

Pte. Clarry Glover, wounded on July 1st, 1916 spent two months in hospitals at Manchester and nearby Radcliffe. Clarry, here seen on the right, along with a friend escort a St. John’s Ambulance Voluntary Aid Detachment nurse on a walk in Radcliffe.

The Burnley comment though more direct — had a sting. “The Burnley Pals have earned themselves a glorious mention in the records for dauntless courage in the face of the heaviest odds. They were some time getting to the Front, but that was not their fault. Though many have fallen the Pals have earned the laurels of fame.”18 All editorials, shared a pride in the achievements of their respective Pals Companies, with sorrow for the losses and sympathy for the bereaved. Over a week passed, however, before any real conception of the Battalion’s disaster spread through the community.

Firm news — and more letters and telegrams — began to arrive on the eve of the annual Summer holiday. In Burnley they began on July 8th, in Accrington and Chorley on July 15th.19 Families hurried from sea-side resorts to get what news they could, or to letters already delivered. In Accrington, Harwood naturally became the focus of many enquiries at the Town Hall and his home. He wrote to the War Office to request an advance list of casualties. He soon discovered no privileges accrued to the raisers of battalions. On July 13th, the War Office replied that a list of ‘other rank’ casualties had not been compiled and that only next of kin would receive news direct from Army Records Office. No advance copies could be supplied to individuals. Harwood, therefore was in the dark as much as anyone else. A week later Rickman, from his London hospital sent Harwood a list of officer casualties — 7 killed, 12 wounded, one missing.

Lt. Heys became Company Commander of ‘Z’ (Burnley) Company.

Burnley was luckier. Contact with ‘Z’ Company in France had not broken down. Lt. Heys, now Company Commander, wrote to the Mayor offering help with individual enquiries.20 Rickman could do little more than send his own condolences to the Mayors of Accrington, Burnley and Chorley. To Harwood he expressed his pride in the Battalion he had cared for for the past sixteen months and his own despair. “No words can express what I feel for the losses, but it may be consolation to those who have lost their all to know the Battalion contributed its share of the offensive.”21

The War Office list of ‘other rank’ casualties arrived in the newspaper offices on August 5th, it listed just 31 wounded. Three days later, 40 killed in action were officially named and thereafter weekly lists of dead, wounded and missing appeared. For most the lists were out of date. As soon as the news of the offensive came through and the truth suspected, local newspapers appealed to readers to supply them with news and photos of the killed and wounded. In this way 17 casualties were reported in Accrington on July 8th. Then, with obituary after obituary, photo after photo, the tragedy unfolded to the readers, there were 32 featured in the paper on July 11th, 40 on July 15th, 32 on July 18th — until they decreased in number in mid-August. The official casualty lists, when finally published, were almost superfluous. The row after row of biographies and photographs had already made its dramatic effect on public morale.

The last of the next of kin of the dead were officially informed in mid-September. Anxieties about those missing increased as time passed. Wives and mothers, desperate for news, advertised in the newspapers — “Mrs. Florence Mercer of Rishton, would be grateful for any news of her son, 15085 L.Cpl. Albert Mercer. ‘Pte. Herbert Aspin of Church. Mother would be pleased if any soldier can give information on his fate.’ Pte. George Stuttard, machine gunner, ‘W’ Company Accrington, any information gratefully received by his parents.”22

Pte. J. Birch of ‘W’ Company, a survivor of July 1st, helped by arranging with his mother in Accrington to receive enquiries from relatives of missing men. Within two or three weeks she forwarded thirty seven names. Pte. Birch devoted all his spare time out of the line in search of information.

Some families were lucky. Their ‘missing’ men turned up wounded in hospital. Others would never know. Pte. John Laffy, who enlisted in the July 1915 recruiting march, disappeared from the face of the earth. On January 25th, 1919, he was still officially listed as ‘missing’. Some information came from comrades in France or in hospital, but often the only information to be gleaned came as ‘he simply disappeared;’ ‘I saw him wounded, then never saw him again.’ Scores of wives and parents, up to their own deaths, clung to the slight hope this gave them that ‘he’ was not dead but might somehow, some day return. Sometimes a letter, sometimes a tattered photograph, the sole object of grief throughout their lifetimes.

Some men died in circumstances so horrific their comrades could not describe them, even many years later. Pte. Ormond Fairweather of ‘Y’ Company saw his friend Pte. Carswell Entw-histle die on July 1st, 1916. “After the war Mrs. Entwhistle begged Ormond many times to tell her how Carswell died, but he always refused. She desperately wanted to know and he couldn’t tell her, both of them were heart-broken.23 Lt. Williams, the only Company Commander to survive July 1st, 1916, was too shocked to be interviewed by anxious relatives, when home on sick leave in August 1916.

Equally with East Lancashire the news of July 1st, 1916 shocked Caernarvon. The close ties formed in the early Spring of 1915 had been maintained by correspondence and courtship and the town closely followed the Battalion’s progress. On July 11th, 1916, copies of East Lancashire newspapers, showing photographs of dead and wounded were posted in Caernarvon shop-windows. The news spread quickly and scores of friends and ex-landladies came to learn the fate of their billetees. On July 21st, the Caernarvon and Denbigh Herald published its own list of 26 officers and men dead and 114 wounded. Most were Accrington men, the names probably supplied by Accrington newspapers. Captain Livesey and Pte. Tom Coady were especially mourned as men popular with the townspeople. For Caernarvon in July 1916 the sorrow from the loss of friends in the 11th East Lancs became intensified by the loss of many local men of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers and the Welsh Brigade at Mametz Wood on July 10th, in the continuing fighting on the Somme.

In East Lancashire, as elsewhere, the impact of July 1st, 1916, lessened in time as other battles, in France and Flanders, in Mesopotamia and Salonika, brought more casualties and losses to local families. The sacrifices of the men of the 11th East Lancs faded and their families adjusted to their grief as best they could.

For the survivors at Louvencourt, Gough’s ‘rehabilitation’ did not last long. With Carter-Campbell returned from sick leave and back in command, the remnants of 94 Brigade, including the 11th East Lancs, moved, on July 8th, north to Calonne-sur-Lys as 31 Division transferred into XI Corps, First Army. A composite company of two officers and 160 men, formed from two depleted companies, again held front line positions in the Neuve Chapelle sector, near Bethune, on July 24th. The line lay in swampy, mosquito-infested country. Trench conditions were particularly foul. Here the Battalion inherited ‘Tupper’, “a huge piebald rat with three legs and one bloodshot eye. He was handed over with trench stores to every incoming Battalion.24 94 Brigade was now so weakened that the combined strengths of the 11th East Lancs, the 12th York and Lancasters and one company of the 13th York and Lancasters equalled only a Battalion.

This postcard was returned to the family of L/Cpl W. Briggs with his effects after his death on July 1st, 1916 (see page 149.) Sent by his fiancee Amelia, it bears a verse on the reverse side which said: ‘I’ll never love another boy but you I’ll never love another boy with eyes so blue Night and day while you are away my love For I’ll never love another boy but you.”

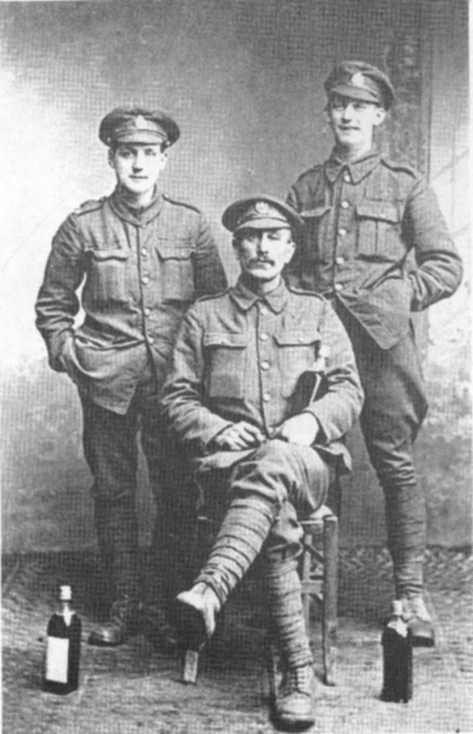

After July 1st, 1916 specialist groups were reformed. Here are Z’ (Burnley) Company bombers ‘Somewhere in France,’ in 1917.

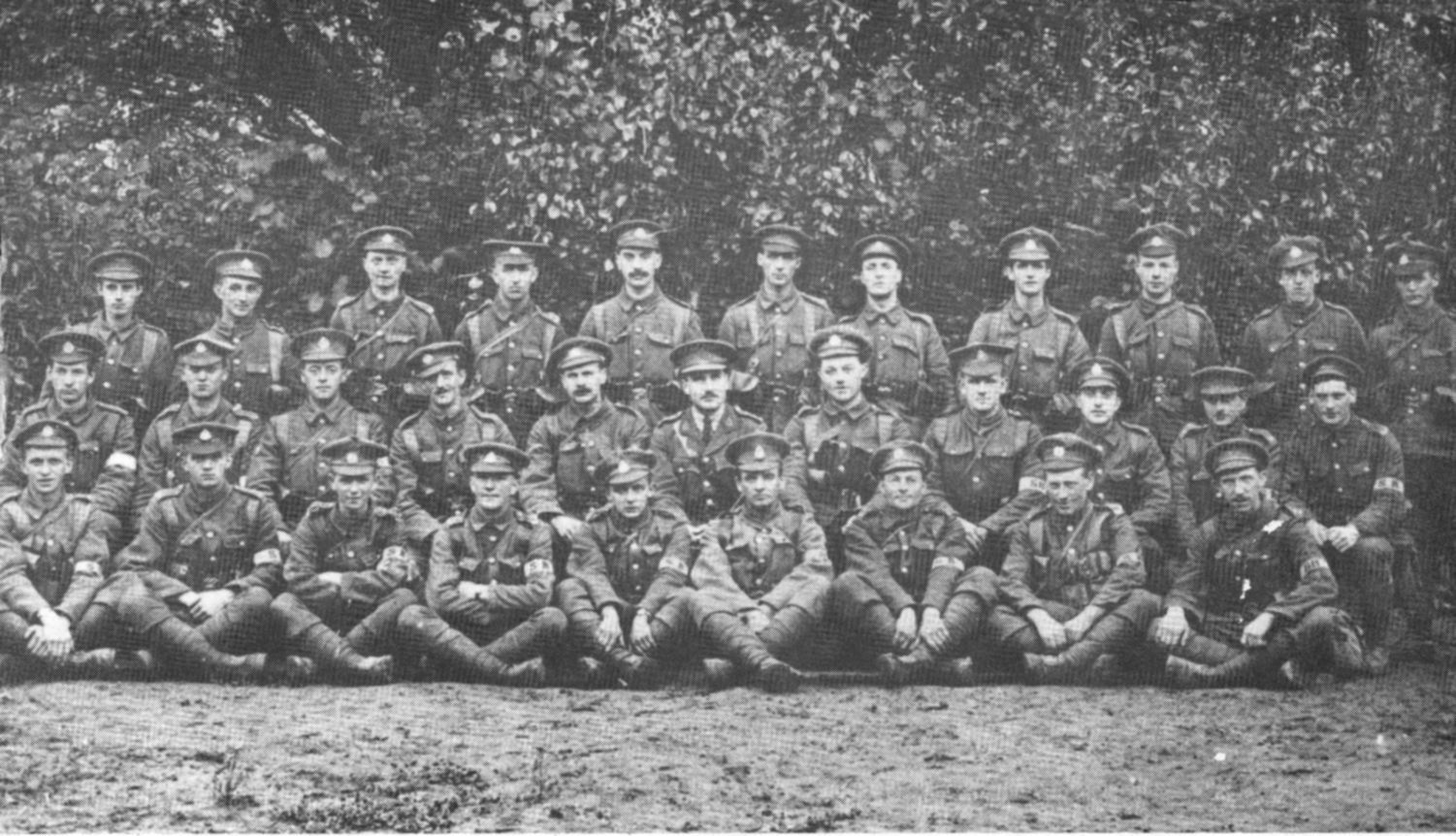

Regimental Band of the 11th East Lancashire Regiment after it was re-formed in February 1917. The former band had been wiped out on the morning of July 1st. All but one were either killed or wounded as they carried out their battle role of stretcher bearers.

After alternating between the front line and the reserve area for almost six weeks, 94 Brigade moved to the area of Festubert of Chorley Territorials ill-fame. Here, in mid-September 1916, a draft of 182 officers and men arrived from Prees Heath.

With these and later additions the subsequent story is of a new battalion. The events of July 1st had radically changed the survivors outlook. Their original enthusiasm had gone — blown away before Serre. With the High Command not so infallible as they once imagined, the war could go on for years. In spite of their misgivings the survivors of the old’ battalion passed something of their ‘Pals’ spirit of comradeship on to the new, although the loss of so many local officers, N.C.O.s and men weakened the old East Lancashire associations. The ‘old’ 11th East Lancs had lost its singular character formed by the close nature of its origins. It had also lost its innocent enthusiasm to become an exclusive group of veterans within a ‘new’ battalion. In this form, in October 1916, and now in XIII Corps, Fifth Army, (formerly the Reserve Army), they came again to Warnimont Wood and to John Copse, in the old shattered front line of even worse ill-fame.

Transport Section of the Pals outside their billet in France in November 1916.

A.O.&T.

In January 1917, 320 reinforcements joined. In the draft were some of those wounded on July 1st, newly discharged from hospital, Pte. Glover and Cpl. Whittaker amongst them, they considered themselves fortunate to return. Other wounded never returned but transferred to other East Lancs. battalions in France, Mesopotamia, Salonika and even Blighty. Still others served with a variety of infantry regiments from all parts of the United Kingdom. Many of the more badly wounded were still in hospital, some to be discharged as unfit for military service. A few, Sgt. Kay, L/Cpl. Challon and Pte. Platt of ‘Z’ Company amongst them, left for officer training and a commission.

Pte. Sayer returned from hospital to the job of training 32 volunteer bandsmen as stretcher-bearers.

“Major Kershaw, then on Brigade staff, told me he wanted me to train the replacement stretcher-bearers. ‘I can’t do it Sir, I’m a bomber.’ ‘Nonsense, I know you were a doctor’s pupil before you enlisted. You used to treat my wife’s mother in Burnley. If you can do that you can teach first-aid.’ From then on I taught first-aid on actual casualties, often under fire from snipers. It was tougher than being a bomber.”

In February 1917, six officers and 200 other ranks joined the Battalion making a total of 700 replacements and returned wounded since July 1916. Thus, the Battalion was brought up to full establishment. In the later groups were many recovered wounded from other regiments, partly a military expediency to flesh out depleted battalions with experienced men and partly War Office policy to break up the community based New Army Battalions whose losses had so affected public morale.

In February 1917, the Germans made a tactical withdrawal of approximately 18,000 yards from their front lines on the Somme to prepared positions known as the Hindenburg Line. The British forces, including the 11th East Lancs, moved up to fill the gap. The route of the 11th East Lancs, through Colincamps and Beaumont Hamel, took them some two miles south of Serre. The Germans evacuated Serre on February 24th and the incoming 22nd Manchester Regiment found the bodies of some of those who had fought their way through the German lines in July 1916. Some men, buried by their enemy, had their names and regimental numbers inscribed on wooden crosses. The remains of others lay where they had fallen or hung, still entangled, on the German wire.25 Two weeks later, in mid March, whilst in reserve at Courcelles and working near Serre on road repairs, it fell to some of the 11th East Lancs to discover the bodies of several of their comrades reported missing since July 1st, 1916.26

Bodies of many of the British dead of July 1st, 1916 lay in No Man’s Land or entangled in the German wire until February 1917 when the Germans withdrew to new positions and British troops moved into Serre. The ravages of rats, weather and time upon human remains are here depicted.

B.C.P.L.

During the early months of 1917 the Battalion had a ‘quiet war’, a mixture of holding and patrolling a relatively inactive sector of the front and training and re-organising behind the line. With newly returned Rickman in command, on June 28th, 1917, almost a year to the day, the Battalion attacked successfully, though at a cost of twelve dead, the German positions in Cadorna trench in Oppy Wood, near Arras. The remainder of 1917 continued ‘quiet’, although patrolling and German shell-fire caused casualties. Only three ‘nil’ monthly casualty returns were made by the Battalion in thirty three months service in France and Flanders. Endless ‘donkey work’ and training occupied their time out of the line.

Signalling Section of the Pals taken at Merville, April 1917.

A.O.&.T.

In February 1918, as part of a large scale Army re-organisation Infantry Divisions were reduced from twelve to nine Battalions, with Brigades reduced from four to three Battalions. 94 Brigade, 31 Division ceased to exist and on February 11th, the 11th East Lancs transferred to 92 Brigade, 31 Division to join the 10th and 11th East Yorkshire Regiments. The partners-hip of almost three years with the 12th, 13th and 14th York and Lancaster Regiments broke up. On the same day these Battalions were amalgamated and re-designated the 13th York and Lancaster Regiment. The 11th East Lancs thus escaped the fate of their comrades from Sheffield and Barnsley — and also the fates of the 2/4th, 2/5th, 7th and 8th East Lancs Regiments, similarly disbanded. Twenty officers and 400 men from the 8th East Lancs joined the Battalion.27 However diverse in make-up, the 11th East Lancs in the re-organisation were paid the compliment of keeping their name and Commanding Officer.

Local leave was available and welcomed. Here two Burnley Pals, with a comrade from the York and Lancaster Regiment (seated) pose in mock seriousness.

The first major trial of the Battalion in 1918 started on the morning of March 21st. After an artillery barrage of almost 6,000 guns, 62 German infantry divisions attacked the British Third and Fifth Armies along a line from the Somme to Cambrai. The 11th East Lancs with the rest of 31 Division rushed to meet the enemy at Hamelincourt, near Arras. For eight long days, until relieved, 31 Division resisted the forces of five German divisions. Between March 27th and April 4th, the 11th East Lancs lost 240 men killed, wounded or missing. Cpl. Earl Whittaker was one killed in the attack.28 In the same period no less than twenty eight awards including the V.C. were won by the Battalion.29

On April 9th, the Germans broke through the line held by Portuguese troops on the River Lys. The 11th East Lancs, with 31 Division, again raced to fill the gap and again suffered heavy losses. By June, however, the Allied Armies steadily regained the initiative. On June 28th the Battalion took part in a successful counter-attack on a German salient in the Nieppe Forest and gained 2,000 yards of ground. Pte. Cheetham, an ex-member of the 8th Battalion, took part in the attack.

“I was in ‘X’ Company as a Lewis Gunner. We saw the Germans running away. I fired just two shots, then the Lewis gun jammed (they were very prone to do so). We thought we were going to miss getting the Germans, but my No. 2 on the gun cleared it and we fired seventeen magazines without a stoppage. We thought of claiming it as a world record!”

On July 1st the Battalion handed over the captured ground to relieving forces.30 By a coincidence the three major attacks of the Battalion were at almost yearly intervals.

German troops look on as a hitherto undamaged village is shelled before they move in to take possession, during their advance in the Spring of 1918.

Re-formed stretcher bearers of the Pals at Merville 1917. Pte. Fred Sayer is seated in the middle row to the officer’s left, Captain De Courcy Keogh.

The Battalion’s final main action — to clear Ploegsteert Wood — started on September 28th. They achieved it at a high price of 370 killed, wounded and missing. Although October and November brought several more casualties, on this day, September 28th, Pte. Fred Leeming died, the last of the original Tals’ to be killed in action.31

The weeks leading up to the Armistice on November 11th, were free of major incidents. The Battalion, now in II Corps, Second Army, was busy pursuing the retreating Germans. On October 25th cheering crowds welcomed them into the textile towns of Wattrelos and Roubaix. On the evening of November 10th, the Battalion halted east of Renaix (Ronse) in Belgium, and settled for the night in barns, outhouses and stables. At 4 a.m. on November 11th, a sentry, Pte. John Pollitt of ‘Z’ Company, challenged an approaching motor-cyclist.

“He dismounted, and to my surprise, threw his arms round my neck and asked where the C.O. was billetted. Then he read me his despatch in code —‘Armistice signed 3 a.m. this morning; all firing to cease at 11 a.m.’. I immediately ran to my comrades to break the good news.”32

In this way all ‘Z’ Company knew of the Armistice before the C.O. It was specially fitting that the bearer of the news was an ‘original’ Pal.

At 9 a.m. as the Battalion assembled to continue their march, Rickman went through the formality of reading them the despatch. At 11 a.m. the Battalion halted and every man listened. For the first time in their Western Front service no sound could be heard — no guns firing, no transport rumbling on the pave, no marching feet. Unbelievably the war was over. At dusk the Battalion entered Grammont (Geraadsbergen), twenty miles east of Brussels. Here, at Grammont, Pte. Andrew Magrath, a bandsman/stretcher-bearer and survivor of July 1st, 1916, in a terrible irony, caught a chill whilst out celebrating Peace and became ill with pneumonia. He died on November 21st, 1918, the last of the original Pals to die on active service.33

Pte. Fred Leeming of Great Harwood, the last original Pal to be killed in action, September 28th, 1918.

CQMS Jack Hindle poses with officers of W’ (Accrington) Company. Written overleaf: Turcoing, France. Almost Armistice Day prior to the last push. The lady was the photographer’s wife.

Pte. A. Magrath, a survivor of July 1st, 1916 caught a chill and died as the war ended thus becoming the last of the original Pals to die on active service.

As the remainder of II Corps advanced into Germany to become part of the Army of Occu-pation, on November 13th, the 11th Battalion started its return march, through Courtrai, Menin and Ypres, to St. Omer, northern France. In spite of an appeal by Rickman to the War Office to allow him to bring the Battalion to Accrington for a farewell parade before demobilisation, the break-up of the Battalion started in December as men in certain occupations, particularly coal-mining, were released.

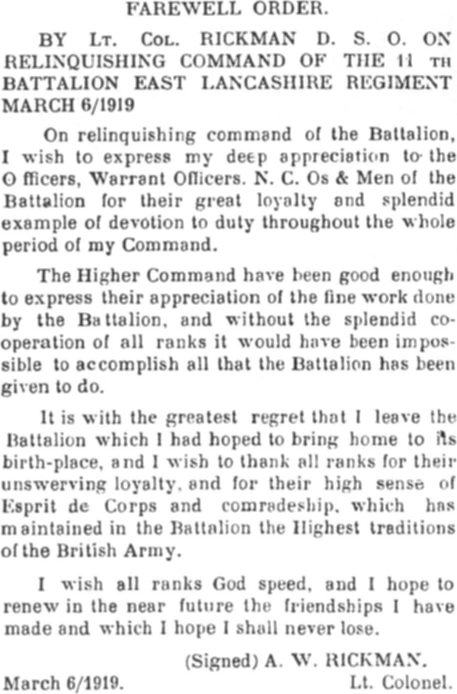

On February 7th, 1919, at St. Omer, a cold wintry day, the Regimental Colours were presented to a fast dwindling Battalion by Brig. Gen. T. de L. Williams. Four weeks later, just four years and one week after his memorable take-over at Caernarvon, Rickman relinquished his command. In his Farewell Order, he spoke of his regrets at leaving the Battalion he had hoped to take home to its birth-place. He thanked all ranks for their unswerving loyalty, their high sense of esprit-de-corps and comradeship and wished them all God Speed.

It took until October 1919 for the Battalion to finally fade away and for the men to return unheralded, unnoticed, to their home towns. For the original Pals the return to East Lancashire saw no cheering crowds, no mayoral speeches — five years had seen too many changes. The Pals themselves, who in their innocent enthusiasm bade their farewells so cheerily in February 1915, were also changed. Too many of their comrades were lying in France, the Middle East and Blighty. Too many had perished on the slopes before Serre. For those left, war-weariness had long replaced the high spirits of Rugeley, Ripon and Salisbury Plain and the impatience of ‘getting to the Front.’ The High Command errors of judgement and organisation of July 1st, 1916 were still seen by many Pals as deliberate decisions made by men indifferent to their fate.34 ‘Not a rat alive’ was still a sardonic joke.

‘Somewhere in France’ 1918. Members of ‘W’ (Accrington) Company. Fifth from the left front row is AQMS J. Hindle. Fourth from right front row is Sgt. J. Rigby, M.M.

‘X’ (District) Company in the public gardens St. Omer in December 1918. By this time men were being demobilised in small groups.

The Colour Party with the Battalion Colours immediately after they had been presented at St. Omer, France, February 7th 1919. On the left of the picture is AQMS Jack Hindle.

The Farewell Order by Lt. Col. Rickman. Every officer and man in the Battalion received his personal copy.

NOTES

1. Survivors of the 12th York and Lancaster Regiment who reached the German wire said they looked towards their own lines and could see every movement. “This being so, any attack by day was hardly likely to succeed”. (Battle report 1/7/16, 12th York and Lancaster Regiment.)

2. P.R.O. WO95/2366.

3. Note to Maj. Gen. R. Wanless O’Gowan, O.C. 31 Division, July 4th, 1916. (File 77/179/T, Brig. Gen. H. C. Rees, A Personal Record of the War I.W.M.).

N.B. Unfortunately, there is no confirmation or otherwise from German sources. The war diaries of 2, 3 and 6 Companies, 169 Infantry Regiment (opposing 94 Brigade) are unavailable ‘presumed lost through enemy action in W.W.I.’ (B.G.K., letter to author dated 3.7.87.)

4. It is estimated as many as one third of those ‘killed in action’ died as a result of wounds, and left to die on the battlefield. (See ‘Face of Battle’, John Keegan, Penguin 1978, P 274.)

5. See ‘The Somme’, A. Farrar-Hockley, Batsford 1964, for a detailed analysis of the artillery bombardment and the counter-barrage.

6. Captain MacAlpine, later asked for his comments for the Official History of the Great War, specifically requested the ‘wheels’ (manoeuvres) to be carried out by the 11th East Lancs during their attack to be explained in detail. The request was ignored. (P.R.O. CAB/190).

7. See ‘Brig. Gen. H. C. Rees, A Personal Record of the War’, I.W.M.

8. P.R.O. CAB/190.

9. The Private Papers of Douglas Haig 1914–1919, ed. R. Blake, Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1952 pp 153–54.

10. Sir Douglas Haig’s Despatches 1915–1919, ed. J. H. Boraston, Vol.1, Dent 1919, p 26.

11. The Private Papers of Douglas Haig 1914–919, p 153.

12. Ibid.

13. ‘The Fifth Army’, Gen. Sir H. Gough, Hodder & Stoughton, London 1931, p 139.

14. July 1st, 1916, was the worst day in the history of the British Army. 57,470 officers and men were killed, wounded or missing. By November 18th, 1916, the official end of the battle, casualties totalled 415,000.

15. Recalled by Edith Roughsedge who vividly remembered the women coming directly into her parents’ shop with the news. She later related the story to her daughter Mrs. Enid Briggs.

16. A.O.T. 8/7/16.

17. C.G. 8/7/16.

18. B.E. 15/7/16.

19. By coincidence the dependents of those of the Chorley Company who enlisted before December 26th, 1914, attended a meeting at Chorley Town Hall on July 10th. Each received on behalf of the men, from the Mayor a Christmas 1914 present of a tin-box containing tobacco and a pencil, etc. from H.R.H. Princess Mary’s Comforts fund.

N.B. (The Accrington Companies, or the survivors, were not to get theirs until August 1919.)

20. Advert B.E. 5/8/16.

‘The Mayor wishes to announce that Lt. F. A. Heys, O.C. ‘Z’ Company, has given him facilities for obtaining particulars as to the killed, wounded and missing of his Company. If any friends of men in the Company have been unable to obtain news, the Mayor will take up the matter with Lt. Heys’.

21. A.O.T. 11/7/16.

22. A.O.T. 2/9/16.

All were ‘killed in action’ July 1st, 1916.

Pte. Stuttard’s parents received official confirmation in April 1917.

23. Conversation with Mr. H. Entwhistle, Chorley 1983.

24. History of ‘Z’ Company Page 39.

25. Those recovered were buried, with men from other regiments, in the Serre Road (1, 2 and 3) group of cemeteries, by troops of V Corps in the Spring of 1917.

26. Very probably amongst these was Pte. Stuttard’s body. (See Note 22).

27. The 8th East Lancs Regiment, formed at Preston, September 1914 (K3), had been in France since July 1915.

28. 15735 Cpl. Earl Whittaker, of Burnley, was reported as wounded, then missing. His body was never found. In November 1918, his wife, firmly believing him alive and a prisoner of war, visited Arras in an effort to find him. For the rest of her life she never believed he was dead. Cpl. Whittaker’s name is on the Arras Memorial.

29. The awards were: V.C. — (2/Lt. B. A. Horsfall of the 1st East Lancs attached to the 11th East Lancs); Bar to the D.S.O. (Lt. Col. Rickman’s D.S.O. awarded after July 1st, 1916); 2 D.S.O s; 7 M.C.s; 3 D.C.M.’s and 14 M.M.s.

30. 31 Division, then in XV Corps, Second Army, transferred to XI Corps, First Army for this operation. Brig. Gen. T. de L. Williams of 92 Brigade later told Rickman he had chosen the 11th East Lancs to attack the strongest part of the German line because they were his most capable troops. This compliment cost the 11th East Lancs 51 men killed in action.

31. 15774 Pte. Fred Leeming, of Great Harwood, is buried, with fourteen other men of the Battalion, at Underhill Farm War Cemetery, Ploegsteert.

32. Letter to ‘Twenty years after’ feature, B.E. 12/11/38.

33. 15860 Pte. Andrew Magrath, of Chorley, died in a Base Hospital in France and is buried in Terlincthon British Cemetery.

34. This belief persisted after the war. Ex-Cpl. R. Bradshaw, addressing Burnley Rotary Club, spoke of ‘94 Brigade purposely massacred and activities shown to the enemy to deceive them and mask preparations further south’. B.E. 11/11/31.