Epilogue

John Harwood’s name did not appear in the 1919 New Year Honours List. During the war no man in Accrington worked harder in his patriotic duty. He put the name of the town in the title of a British Infantry Battalion and an Artillery Brigade (158 (Accrington and Burnley) Howitzers, R.F.A.) His appointment by the War Office as their military representative on the Accrington Military Tribunal took place in January 1916.1 In this lay his downfall.

The Accrington Military Tribunal quickly gained a reputation for harshness and bias. Objections to military service on the grounds of conscience were subjected to humiliating interrogations, with questions often deliberately phrased to produce laughter from an audience there ‘to see the fun.’ Shop-keepers and the self-employed were often exempted without hesitation. This rarely happened to employed persons, regardless of circumstance. As early as March 1916, a current of ill-feeling in Accrington led Philip Snowden, M.P. for neighbouring Blackburn, to criticise Harwood in a debate in the House of Commons, as “a prominent Conservative, instrumental in deciding whether political opponents should or should not, be granted exemption.”2

The good regard held for him in his home town had become diminished by his zeal and lack of objectiveness. Perhaps because of this he got neither recognition nor reward from his country. In 1919, aged 70, tired and worn-out, he retired from public life.

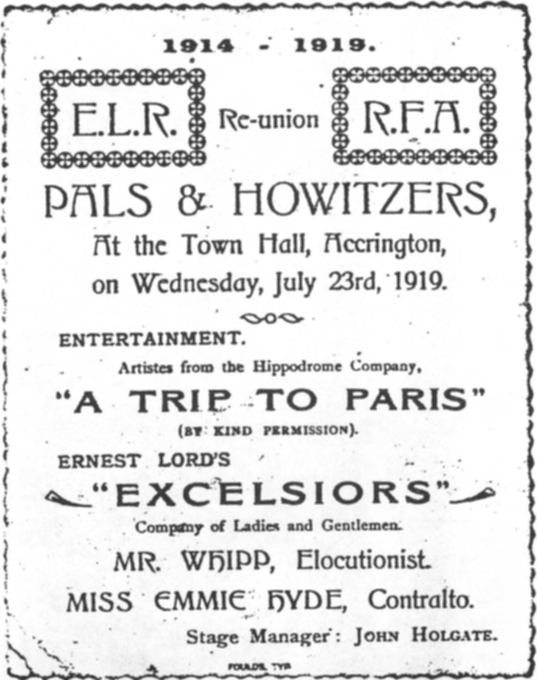

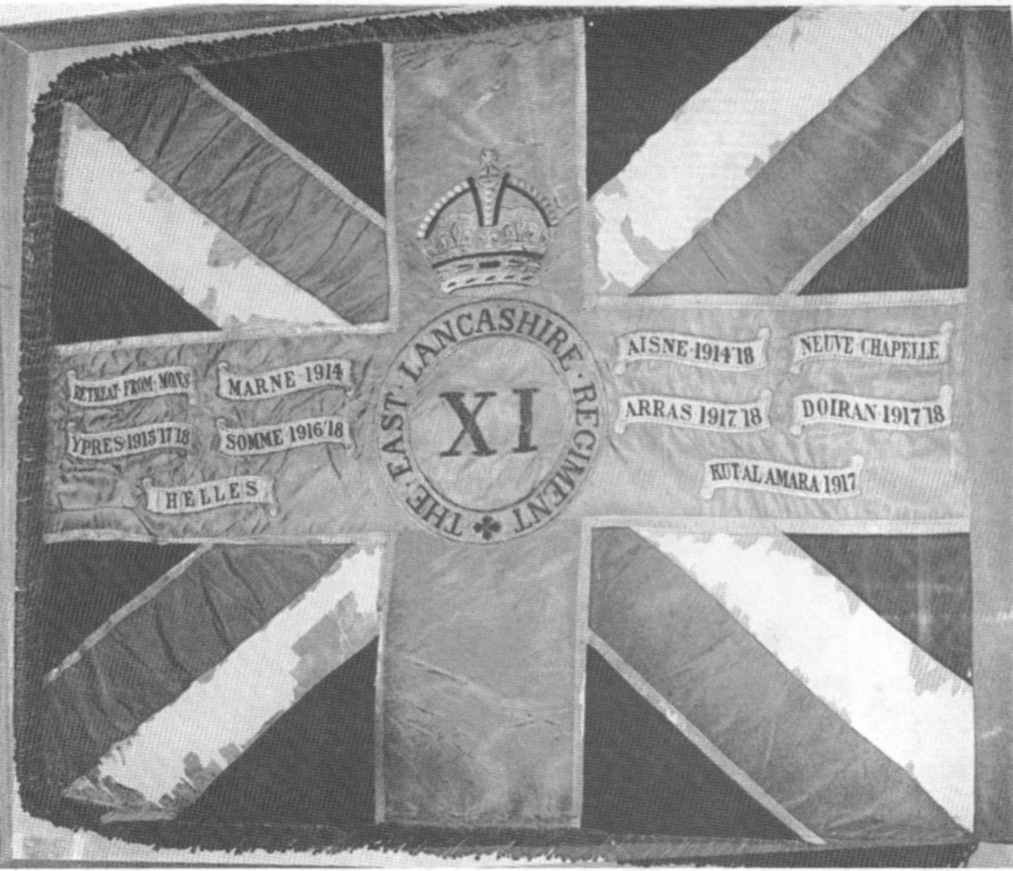

Harwood, nevertheless attended three functions concerning the Battalion. He helped organise a combined ‘welcome home and reunion’-party for the Battalion and 158 Howitzer Brigade in July 1919. On October 18th, 1919, as guest of honour he attended the ceremonial handing over of the Battalion Colours to the town of Accrington by Lt. Col. Rickman’s successor, Lt. Col. Ingpen, D.S.O.3 In his final public act Harwood laid the first wreath in memory of the fallen of the Battalion at the ceremonial unveiling of Accrington War memorial in Oak Hill Park on July 1st, 1922.

When published, the order of procession to the ceremony became a source of controversy. The Accrington Company of the 5th East Lancs. Territorials — some but youths too young to have served in the War — were to lead. Following were simply ‘Ex-Servicemen’, i.e. any who were eligible and willing to march. A group of ex-Pals protested. They considered that they, as an ‘Accrington’ Battalion, held the right to lead the procession. The protests revived wartime resentments by the Territorials and their families who often felt the Pals received an undue share of publicity and ‘glory’. The controversy ended and the Town Council’s original intention fulfilled, when ex-Pals and ex-Territorials marched side by side. John Harwood laid the first wreath as the sole concession to ‘his’ ‘Accrington’ Battalion.

John Harwood, J.P. Mayor of Accrington

John Harwood attended this welcome home’ and grand reunion for the Pals and Howitzers in the Town Hall, Accrington in July 1919. A high tea in the Wesleyan School, Union Street preceded the Smoking Concert and Social which commenced at 7 pm.

Laying wreaths on the steps of Accrington War Memorial after the unveiling ceremony on July 1st, 1922.

A general view of Accrington War Memorial after the unveiling ceremony.

The reluctance of Accrington Town Council to have any special post-war relationship with the Battalion is evident in the town’s absence from any association with the villages on the Somme. Burnley, home of many 1st Battalion men as well as ‘Z’ Company, in 1920 adopted Miramont, Colincamps and Courcelles and helped finance the rebuilding of those villages.4 Official links ceased in 1930 with a visit by the mayor of Burnley to lay wreaths on the graves of Burnley men in Euston Road, Queens and Railway Hollow cemeteries. Nevertheless, no public memorial to the Burnley Company was proposed or considered by the Town Council.

In contrast, Chorley Town Council, although at first reluctant, did pay tribute to its Chorley Company. As early as November 1916, a group of women led by Miss Knight proposed at a public meeting, the erection of a home for twenty five maimed soldiers to be known as “The Pals’ Memorial Home for Crippled Soldiers.” This led immediately to bitter controversy. Most men prominent in Chorley public life, including Dr. Rigby in his role as a Town Councillor, wanted instead the memorial to be for all the fallen of Chorley and forced a postponement of the idea. The idea, in time, died. Six years passed before Miss Knight could commemorate ‘her’ Pals in her three Golden Books of Remembrance in Chorley’s Memorial Room in Astley Hall. Chorley Town Council finally played their part with a Chorley Company Roll of Honour listing 55 dead and 158 survivors, and three large framed photographs of ‘C’ Company taken in 1914.5

Unlike East Lancashire, Sheffield kept contact with Serre and formed a post-war friendship with the village. Within the village is a Memorial in memory of the men of the 12th York and Lancaster Regiment who died in the attack. On July 5th, 1936 a hundred strong civic delegation from Sheffield attended a memorial service in the newly opened Sheffield Memorial Park. The event solely concerned Sheffield and Serre. Of Accrington, and the 11th East Lancs Regiment — no mention. The reason can lie only with Accrington Town Council’s lack of interest. The Sheffield Memorial Park, by a strange irony, stands partly on ground held by the 11th East Lancs Regiment on July 1st, 1916.

The 1920s and early 1930s passed with most of East Lancashire preoccupied in surviving the inter-war industrial depression. (As early as 1919, Accrington had some 11,000 unemployed). The heartbreak of the war continued. Each November 11th, looms and lathes stopped at 11 a.m. and schoolchildren gathered at War memorials, for silent remembrance.

July 1st, became a date filled with poignancy. Each year scores of family ‘In Memoriam’ notices appeared, each year editorials condemned the war and the tragic losses on the Somme. In 1926 the ‘Accrington Observer’ compared July 1st, 1916 with the economic chaos of industrial life of the General Strike — “As we revere the memory of those who fell at Serre, we reflect if some of those whose mission it was to give us a brighter and better England would have played their parts as resolutely as those who sacrificed their lives to win the war, the years that followed would have been a good deal less troubled and uncertain.”6

The survivors of the war — and the widows and children of the dead — continued to endure the indignities of the ‘Means Test’ and the semi-starvation of unemployment. Some escaped by emigration. Pte. Bloor, Pte. Clark and Pte. Davy went to Canada, Cpl. Bath to Australia. But the shadow of war remained. The Battalion still had its casualties. Amongst many, Pte. Varley died, aged 36 in 1924, directly of pneumonia, indirectly from gassing. A parsimonious government denied his widow a war pension because the medical authorities diagnosed his death as ‘natural causes’. Sgt. Rigby M.M., wounded July 1st, 1916, wounded in April, in August and again in September 1918 died, aged 41, in 1928 of Tuberculosis contracted as a result of war service.

Sheffield Memorial Park, by the copses in France.

Serre village in 1932, the houses have been rebuilt and the villages have returned to normal life.

IWM

Col. R. Sharpies.

By a sad coincidence four men closely concerned with the Battalion’s early days died in the 1920’s; Captain Slinger, aged 43, in October, 1923; John Harwood, aged 74, in December of that year; Lt. Col. Rickman, aged 51, in October 1925 and Col. Sharpies, aged 79, in August 1929.

Lt. Col. Rickman’s accidental death (his clothing caught in the flywheel of an electricity generator) shocked his many admirers, but Col. Sharpies’ death broke the final link with the memorable, often semi-comic, days of the autumn and winter of 1914. Each man had his favourite memory of the Colonel’s amiable discipline — his sending home, with mild reproof, those who paraded with a ‘pint or two’ inside them; his taking a parade, in full military uniform except for a workman’s flat cap, ‘to keep the wind out;’ the occasional late parade because of pressing business matters in his solicitor’s office; and his admonishment to a private (age 40) who swore at a Second Lieutenant (age 18) — ‘don’t use that naughty word to a lad again.’

Col. Sharpies’ paternalistic eccentricity and his men’s good-natured respectful, response helped, no doubt, form the good character of the Battalion. No greater contrast with Lt. Col. Rickman’s command from 1915 to 1919 and those early formative years can be imagined, but the Battalion’s active service performance and reputation had its origins in the early leadership of Col. Sharpies.

The spirit of comradeship which produced the protests of 1922 did not last. No organised group of ‘ex-Pals’ formed in any of the three main towns, although individuals did charitable work within the newly-formed British Legion branches.7

Many personal friendships, strengthened by the shared experiences of the Somme, continued to endure. Old comrades, often unknown to the bereaved family, but warned by the ‘bush telegraph’, would turn up to pay their last respects at the funeral of an ex-Pal. In Burnley, when Major Ross, a bachelor with no family died alone, ex-Ptes. Edwards and Walton, ex-Sgts. Kay and Barrow and ex-Capt. Kershaw were his chief mourners. From this accord in 1935 emerged a revival of interest in the Battalion. A small group led by A.Q.M.S. Hindle organised the ‘First Annual Reunion’ of the 11th and 12th (Reserve) Battalions in Accrington in April 1935.

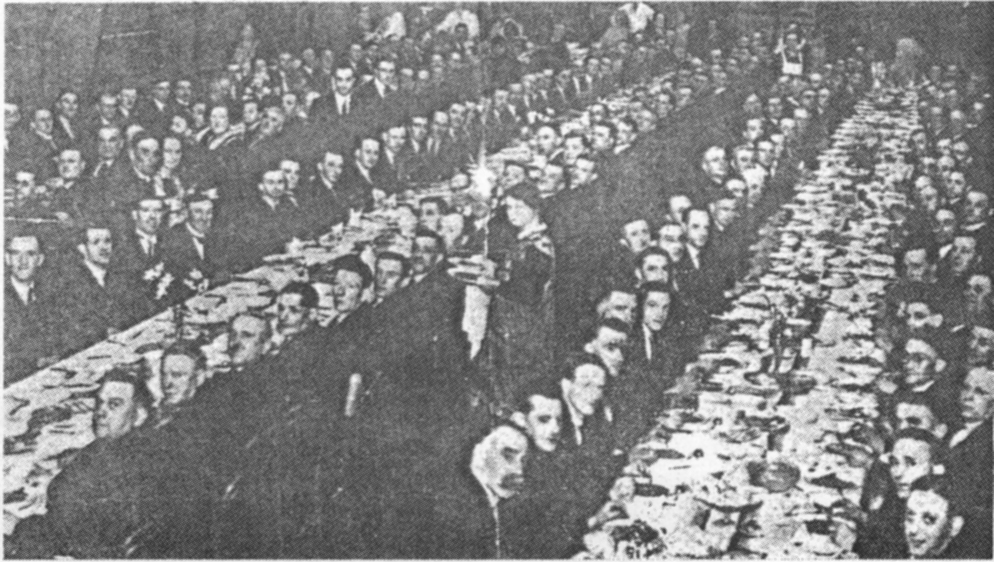

The event was an immediate success, three ex-Officers and 318 ex-N.C.O.s and men attended. Although most came from Accrington and Burnley (only two from Chorley) men travelled from other parts of the country to be there. With the exception of the ex-officers who, from 1919 until Lt. Col. Rickman’s death in 1925, held their own reunion dinner every July 1st, some met old comrades for the first time since July 1st, 1916. For many the reunion became a deeply moving experience, as men thought long dead met again.

The ‘Hindle’ group organised other events. On July 1st, 1936, they placed a large wreath ‘in remembrance of the Pals who gave all’ on the Accrington War Memorial. A similarly worded ‘In Memoriam’ notice appeared in the local newspaper. At the group’s suggestion the Battalion Colours were removed from the Accrington Town Hall Council Chamber where they had hung since 1919. On November 6th, 1938, over a hundred Pals led by 80 year old ex-C.S.M. Muir, escorted the four man Colour Party into St. James’ Parish Church for the Colours to be formally blessed and laid up. Three months later, on February 20th, 1939, again in St. James’ Church, the lamp of the Accrington branch of TocH was dedicated to the officers and men of the Battalion.8 Regrettably, the 1939–45 war ended the revival. Two hundred attended the fifth and last reunion dinner in April 1939.

First Annual Reunion of the Pals, held in the Drill Hall, Accrington in April 1932.

Regimental Colours of the 11th East Lancashire Regiment in St. James’ Parish Church Accrington. Because of the deterioration of the white fabric the Colours were mounted in a glass case in 1968.

Public interest faded for almost thirty years, the only reminder being the annual ‘Somme Sunday’ service held in Blackburn Cathedral on the Sunday nearest July 1st, to commemorate all the East Lancs Regiment war dead. In 1966 the Accrington Observer, ever since 1914, a supporter and friend of the Battalion, suggested a special service in their memory be held in St. James’ Church on the 50th anniversary of the first day of the Somme. Public interest quickened and many hundreds attended.9 Unfortunately a public squabble also began. This revived the old differences with local Territorials. Pte. Bloor, who since his return from Canada in 1934, made an annual pilgrimage to the Somme, suggested the town organise commemorative events every July 1st. This provoked a reply in the Accrington Observer by the local British Legion secretary (an ex-Territorial) saying not only the Pals were worthy of special remembrance. Other correspondents joined in and some acrimony arose. Bloor’s idea faded away, again leaving remembrance to individuals.

The controversy nevertheless rekindled interest in the Battalion. In February 1969, an article appeared in the Accrington Observer. Full of inaccuracies (e.g. “On July 2nd, 1915, the Battalion suffered terrific casualties.” “At the roll-call only forty men responded”) the article tendered the improbable view of the Battalion not being commemorated in Accrington because there were so few survivors. It concluded “Accrington never made a great deal of the memory of the Pals — the sheer size of the disaster rather numbed the imagination.”10 The The happiest cameraderie was once again in evidence at the Argyle-strect Drill Hall on Saturday, when the fifth annual reunion of. the “Pals” Battalion (11th Service Battalion, East Lancashire Regiment) drew an attendance of over two hundred. A full report of the proceedings appeared in Tuesday’s “Observer.” “Observer” Photo article neglected to say only one Company of four came from Accrington so implying the forty respondents to the roll-call to be solely from the town. The article ignored the wounded who served again and ignored the numbers who attended the reunions of 1919 and 1935 to 1939. From such stuff myths are made. The story, with all its inaccuracies and distortions found many believers — except among those who served in the Battalion.

Fifth and last Annual Reunion held in March 1939.

A.O.&T.

A group of ex-Pals march to St. James’ Church on Rememberance Sunday 1952. Harry Bloor front right, Fred Illingworth front centre.

Similar articles subsequently appeared with some frequency in East Lancashire newspapers. All continued — and added to — the myths and exaggerations. July 1st became, not a time for simple remembrance, but a focal point for an emotive imagery of the wholesale massacre of Pals. This overrode the normality of the experiences, horrific as they were, the Battalion shared with many other British and Empire Battalions on July 1st, 1916, of whom several suffered more killed and wounded than the ‘Accrington Pals’.11

The myths, together with a romantic view of ‘little’ Accrington raising its ‘own’ battalion in competition with the major cities of industrial Britain, placed the ‘Accrington Pals’ as the epitome of the Kitchener New Army Battalions of 1914. In the minds of many the ‘Accrington Pals’ represent those, who in the innocence of youthful ideals of patriotism and service, ‘started early in the fight.’ They represent those whose abstract ideals were destroyed — with their youth — in the terrifying realities of the slaughterhouse of the Somme. Myths notwithstanding, by their loyalty, endurance and sacrifices, the 11th East Lancs earned the right to be so honoured.

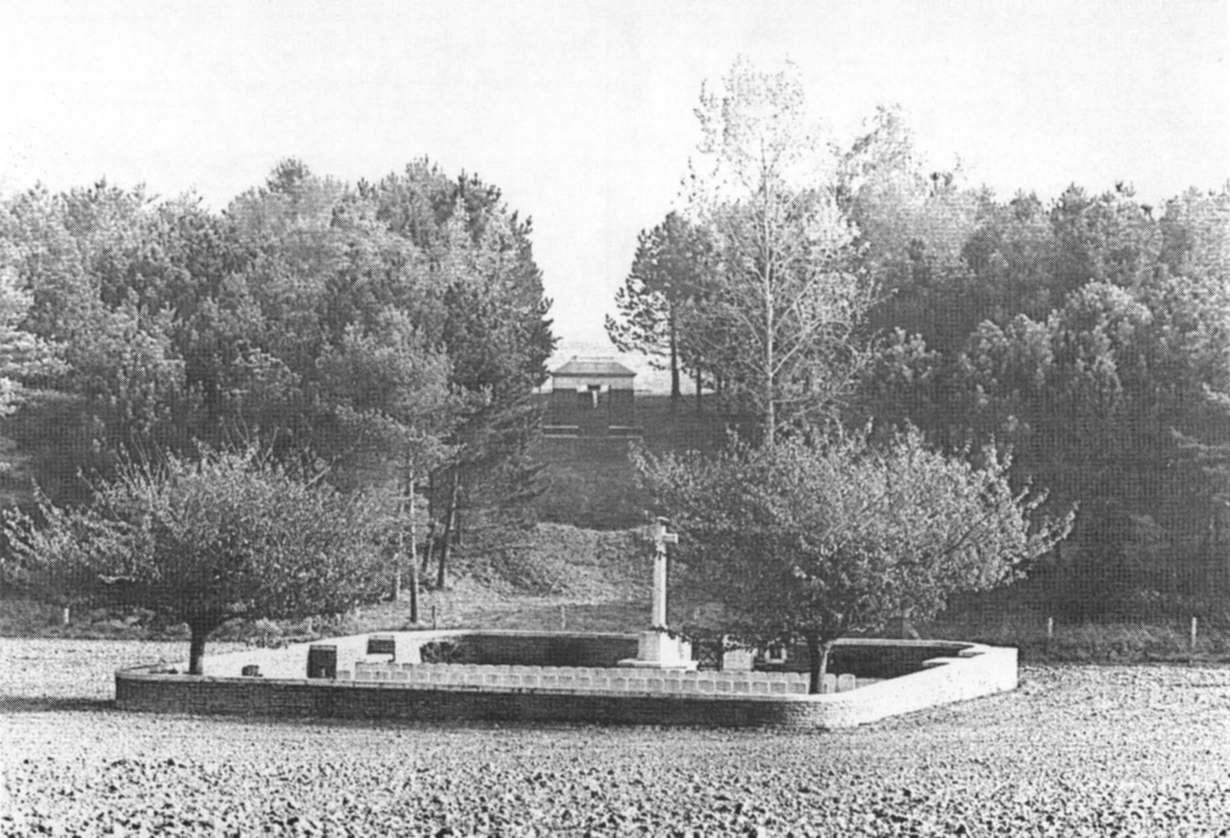

Railway Hollow Cemetery situated directly behind the old British Front Line in the fields in front of the village of Serre. Luke copse is on the left and Mark Copse is on the right, with Sheffield Memorial Park between.

The battlefield today looking from the old German Line towards the line of trees which were once the three copses Mark, Luke and John (Matthew Copse is no longer there.)

Queens Cemetery, in the foreground, stands in the old No Man’s Land.

Memorial to the Missing, Thiepval commemorates the officers and men who fought and died on the Somme from July 1915 to February 1918, and have no known grave. The names of 135 officers and men of the Accrington Pals are inscribed on the memorial.

NOTES

1. Under the Military Service Act of January 1916, objections to military service on family, moral or religious grounds had the right to apply for exemption before a Military Tribunal held in public. The Tribunals consisted of a small group of local civilians, representing different interests in the town, plus a Military Representative.

2. Hansard, Parliamentary Debates, House of Commons, No. 191, Volume LXXXI, March 1916.

3. The last man of the Battalion was demobilized on October 11th, 1919. The four N.C.O. Colour Party volunteered to stay on until October 18th. The Battalion officially ceased to exist on October 20th, 1919, when its records were delivered to the East Lancashire Regiment Record Office, Preston.

4. The movement for the adoption by British towns of devastated towns and villages in France, opened at a meeting at the Mansion House on June 30th, 1920. Lord Derby wrote to the Mayors of Lancashire towns expressing the hope they would participate. In East Lancashire, Blackburn adopted Perronne and Maricourt; Burnley adopted Miramont, Colincamps and Courcelles. There is no record of any response by Accrington to the appeal.

5. The ‘Memorial Room’, in Astley Hall, Chorley, dedicated to the men from Chorley who died in the war, was formally opened in 1922 as the town’s war memorial.

6. A.O.T. 3/7/26.

7. Apart from the Regimental Colours in the Town Hall, the only visible token in Accrington was a privately owned Pals Cafe, which served the mills and workshops in the Bull Bridge area during the 1920’s. Blackburn Corporation Museum and Art Gallery displayed a Maxim heavy machine-gun captured by the Battalion in the German retreat in 1918 and presented to the museum in 1919.

8. Toc H (Army signalling code for T.H.) started in December 1915 in Talbot House, Poperinghe, Flanders, as a chapel and club for servicemen. Toc H became a world-wide, inter-denominational, Christian fellowship for the continuance of comradeship and social service. The Accrington branch opened in February 1928.

9. On the same day Burnley Lads Club held their own commemorative service for Captain Riley and the Club members who gave their lives in the attack.

10. A.O.T. 15/2/69.

11. See The First Day on the Somme’, App. 5, p 320.

These casualties should be regarded as minimum figures from a variety of sources.