There’s a story I like about Wayne Shorter. It’s told in Footprints, Michelle Mercer’s biography of Shorter, a book that folded in his voice and which may have to serve as his autobiography, unless he writes a proper one. It is told by Hal Miller, a jazz historian who sometimes traveled on tour with Weather Report, the band Shorter played saxophone with from 1971 to 1985.

“I remember once I asked Wayne for the time,” Miller told Mercer. “He started talking to me about the cosmos and how time is relative.” Miller and Shorter were waiting somewhere—an airport, a train station, a hotel. The band’s keyboardist, Joe Zawinul, who took charge of such matters as what the road crew was supposed to do and when, set Miller straight. “You don’t ask Wayne shit like that,” he snapped. “It’s 7:06 p.m.”

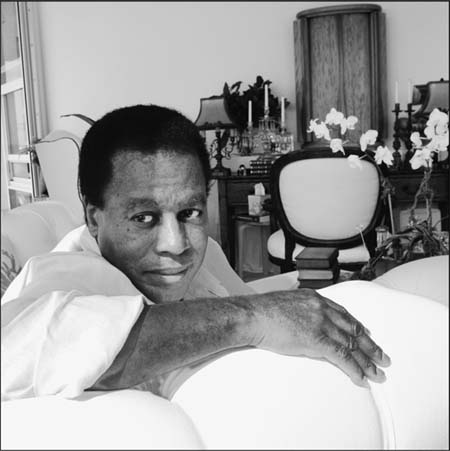

I have had similar conversations with Shorter over the years. Not long after I read that book, I got in touch with him, hoping we could listen to some music that he admired, as a way into having a conversation about music and, ultimately, about his own work. I figured that the exchange might be one ballooned 7:06 p.m., but I also figured that as long as we were listening to the same music at the same time, the conversation wouldn’t break down. After he finished a European tour with his quartet, we got together on a December afternoon at his home in Aventura, Florida, less a town than a thicket of tall condominium towers near the ocean.

Since he went back on the road with an acoustic jazz quartet in 2001, after an extended period of fits and starts following the breakup of Weather Report, Shorter’s shows have built up a consensus of awe seldom encountered in the splintered world of jazz. He has been playing his own compositions—from his days with the mid-1960s Miles Davis Quintet to pieces from later solo records—and establishing that there is a way of writing tunes for a hard-core jazz group that are not codified by style as soon as they hit the music paper. The pieces are open-ended, a function of his temperament, as a few hours in his company makes clear.

Shorter, born and raised in Newark, New Jersey, has a cast of mind that makes his jazz almost zenlike. His songs are succinct, clever, sometimes even cute, but they also pose unanswerable questions. Many of his songs from the mid-1960s, when he was turning out one small masterpiece after another—“Fall,” “Limbo,” “Nefertiti,” “Et Cetera,” “Orbits”—are dressed in odd phrase lengths and rarefied harmonies. They can seem too fragile to be bruised in a nightclub.

A test of jazz musicians and composers is whether their writing can succeed outside their own creators’ preferred context: a trio, a quartet, a big band, or whatever. Wayne Shorter’s “Footprints,” “Speak No Evil,” and “Infant Eyes” have been common standards for a long time now, played in many different types of bands, with other compositions of his approaching that level. Likewise, it’s not just with his quartet that he can slay audiences. I once saw him walk on stage for a single solo, on a version of Antonio Carlos Jobim’s “Dindi,” with the singer Flora Purim. It was spectacular, a grainy, evocative, playful thing that kept striking earthy and far-out patterns. He had just turned seventy-one at the time and gave no indication of having decided that he could rely on a boilerplate version of his own sound.

Standing at the windows of his apartment tower, Shorter pointed out the nearby buildings where Whitney Houston and Sophia Loren lived, then showed me a catalog of new work by his wife’s cousin, a sculptor from São Paulo. (In 1999 he married Carolina dos Santos, a singer and actress, his third wife.) Finally, he produced a box set of music by Ralph Vaughan Williams, conducted by Sir Adrian Boult. “I got something good for you,” he said.

I had been expecting classical music. Some of his recent works have been rearrangements, for orchestra and jazz quartet, of Villa-Lobos and Sibelius. I thought he might pick Stravinsky, the bebopper’s idol. But this choice made sense, too; the English composer Vaughan Williams, directly or indirectly, influenced many postwar film composers, and if there’s one artistic stimulus that Shorter always seems open to, it is the movies.

Small and cheery, dressed in I’m-not-going-outside-today clothes and bedroom slippers, he spent some time struggling to set the Krell home-theater preamp so that it could play a CD. I was forming a suspicion that he didn’t listen to music much.

“Hey, man, the Krell. You ever see the movie Forbidden Planet?” he asked. “There was this planet full of people called the Krells. And nobody had been there from Earth—the explorers from Earth didn’t see anybody when they arrived. But they all went to sleep one night in their spacecraft, and you hear the first sound of special effects that really came to the fore in movies—this chrrmmm! Chroooom! And you see the ground that’s been depressed by huge footprints, not human . . .”

He first chose the opening of Vaughan Williams’s Symphony no. 1: “A Song for All Seas, All Ships,” composed in 1910, with orchestra and choir singing lines taken from a poem by Walt Whitman. After the fanfare, twenty seconds into the piece, as the strings begin to rise dramatically, Shorter smiled. “Life, that’s what he’s saying,” he said. “It’s a metaphor for life.”

It is superhero music. (Shorter, who is not cagey about his enthusiasms, wore a blue Superman T-shirt that day.) “Behold,” the chorus sang out again, “the sea!” The cymbals crashed, illustrating a wave, and then the tempo fell off, the sound dispersing like spray.

“I like that,” he said. “It’s almost saying, ‘Look at your life.’ If anybody wants to commit suicide, just take a look at your life. Look in the mirror. Because we are the ship.” The brass lines grew denser. “I like that, the little line in the bass going down, the contrary motion. It’s like describing a thing that you don’t need to worry about. It’s like, life should be awesome. The lyrics are saying something else, but there are some things that lyrics cannot express.” The chorus came back again. “Power!” he said, grinning.

“I only heard this piece eight or nine months ago,” he explained, motioning to the box set we were listening to, which he had just unwrapped. “But Ralph Vaughan Williams, I’ve been tracking him since I was about sixteen or seventeen. I used to listen to a program called New Ideas in Music, which came on every Saturday at noon on the radio.”

Shorter’s mother worked for a furrier in Newark. His father was a welder at the Singer sewing machine factory in Elizabeth, New Jersey. As Footprints tells it, Shorter and his older brother, Alan, cultivated radical artistic temperaments, encouraged by their parents. By their teenage years, they had formed their own clique of surrealists.

In 1950, when bebop was still largely a thing of mystery to high schoolers outside of the big city, Wayne and Alan performed Dizzy Gillespie tunes at a school concert, dressed in wrinkled suits and galoshes, pretending to sight-read the newspapers on their music stands. In those days, Shorter painted the words “Mr. Weird” on his saxophone case, and he still could; he speaks in disjunctive bursts, frequently lapsing into silence halfway through a sentence. Sometimes you think you get his meaning, and then, sadly, you discover you couldn’t have been following a colder trail.

But in many ways his youth was quite normal for the 1940s: filled with radio, comic books, and movies. His study, where he composes at a small desk with score paper, pen, Wite-Out, and a half-size keyboard, is filled not with music CDs but with videocassettes and laser discs: Dean Martin celebrity roasts, For the Love of Ivy, The Bad Seed, Quilombo, The Ugly American.

Next Shorter wanted me to hear Vaughan Williams’s “The Lark Ascending,” which he performed both in the concert band at New York University, when he was a music education major, and then in the army band during his service from 1956 to 1958. (He was stationed in Fort Dix, New Jersey.) But as I found out later when I bought my own copy of the box set, there is a manufacturer’s mistake in the track numbering for that particular disc. We couldn’t find the “Lark,” so we settled instead for “Norfolk Rhapsody no. 1,” composed in 1905 and 1906, which he also likes.

A clarinet bubbles up with a tendril of a line, following a violin; they are complementary versions of the same melodic idea. The strings slither quietly underneath. As the clarinet and violin gestures keep repeating, a tense feeling of stasis begins to take over. “Happening,” he muttered. Later in the piece, when further iterations of the line move higher, through different keys, it reminded me a little bit of his own “Nefertiti,” from 1967, with the Miles Davis Quintet, whose long melody tensely runs a five-note pattern through different chords, without a solo ever actually coming to pass.

“We’re gonna get into some Symphony no. 4 next,” he said. He put on the opening of the first movement, a dramatically brooding thing. “I guess some of the early writers of movie music got this,” he said, as a noirish romantic theme emerged from a thunder of kettle drums and bass trombones. “Like the John Williams music in the film of Hemingway’s The Killers.”

I asked if he particularly likes music that suggests something about human temperament. “Yeah!” he said, brightly. “And also going . . . ,” he said, making a pushing-out-into-the-universe gesture. “You know, the unknown! I’ll put on the scherzo.”

The gremlin music of the scherzo heated up, turning into a passage of gnarled, menacing little three-note jabs-and-parries in the strings and brass. “You know that Coltrane got some of that stuff,” he said, mimicking hands-on-the-saxophone. “Duhdeluh . . . duhdeluh duhdeluh . . .”

Shorter and Coltrane were close; he was Coltrane’s first significant long-term replacement in Miles Davis’s band, and had been very early to understand and absorb Coltrane’s improvisational style. (He saw Coltrane with the Davis band, in Washington, D.C., probably in November 1955; David Amram, the French horn player, remembered meeting Shorter that winter at the 125 Club in Harlem and hearing his raves about Coltrane.) Shorter chose to emulate where he thought Coltrane was going rather than where he had just been, and they ended up in very different places, Shorter with epigrams and Coltrane with epics.

“It’s like something from a movie! ‘Titanius! Agamemnon!’ ” he cried, assuming an actorly baritone. “It’s like Errol Flynn fighting with Basil Rathbone: chik-chik-chik! This is happening,” he said.

The music changed again, becoming less agitated and more hopeful. “And here’s the seafaring stuff, the sailor thing . . . or it could be astronauts. We need a large vehicle to get beyond this gravity and away from our decadent thinking,” Shorter intoned.

He still wanted to play me more. He found the dark, almost violent Symphony no. 6—Vaughan Williams finished it not long after the bombing of Hiroshima—and went right to the scherzo. “There’s a little Stravinsky in there,” he said, “but that’s all right; the pagan thing.” Then, about two minutes in, a tenor saxophonist enters, as the music scales down to a trio and shifts harmonically, with a new melody. “Dig him!” Shorter crowed. “He came right out of the wall! I like how that whole thing came out from the side.”

In the mid-1970s Shorter moved to Los Angeles and became involved with Soka Gakkai International, the American-based group associated with Nichiren Buddhism—the sect that chants Nam-myoho-renge-kyo. (His commitment to the practice shortly followed that of Herbie Hancock, his partner in the Miles Davis group of the 1960s.) The philosophy of Nichiren Buddhism—particularly the idea of “the eternal self,” and taking responsibility for one’s life—serves as the root of most of his big ideas.

“It comes down to people,” he said, “people awakening to this whole thing called eternity. And not thinking that ‘you gotta do it now,’ and ‘if you don’t do it now you’ll never do it because you only live once.’ If you think you only live once, you’re gonna have war. You’re gonna have bank robbers. They’re not gonna study or care about anyone else. It’s like Enron: ‘we need a quick way to get a house in the Bahamas.’ When a person gets rich, they’ve got half of something. But the half gets confused with the whole. If I thought that 106 South Street was the whole world—which I did, it was the house where I grew up—then I was an isolationist. If I’m still thinking that way right now, I’m a hell of an isolationist.

“People talk about connecting all the dots. But there have been experts at disconnecting dots. You know, the dogmatic thing is to say, the only time you’re gonna have to redeem yourself is now. And if it’s too late, you’re gonna go to hell”—he made a severe face—“or, heb’n,” he said, putting on a dumb, credulous voice. “I don’t believe that shit.”

He went on. “It’s no great mystery about why things are the way they are. Doubt, denial, fear, trepidation reinforce the artificial barriers to the real, the barriers that keep us from going into the real adventure of eternity. If you don’t believe we have eternity, it doesn’t matter; it’s there. You’ll never be bored. I think you’ll always be you, and I’ll always be me. When you say ‘what is life?’—well, life is the one time you have an eternal adventure.” He looked pleased. “Sounds like a contradiction. The one time you have an eternal adventure. I like that! It rubs against itself; it makes sparks. To me those sparks are fuel.”

“I don’t really listen to music,” he said later in the day, not to my great surprise. “I listen to music when I’m making a record; I listen to what we’re doing. But I don’t listen to music because there are not that many close sequences of chance-taking over any period of time. You have to wait until someone has the courage to come and jump into deep water. You have to wait a long time for a Marlon Brando. You have to wait a long time for a good close encounter of the third, or fifth, or tenth kind. I have Steven Spielberg Presents: Taken, the miniseries,” he said, excitedly, “and it’s still in its cellophane. I’m waiting to match that kind of time, to see it all at once, when it can really be appreciated—not just to see it because I have it.”

What has he heard in passing lately that he liked?

“Occasionally I will hear twenty seconds of something in a film score,” he allowed. “I liked John Williams’s opening music to Catch Me If You Can. I like the depth and breadth of sound that he can get to reflect the vastness of something—of space. I like James Newton Howard, too, his way of not always seeming like he has another film to score. James Horner, I liked his score for Glory, with the Harlem Boys’ Choir. I like Bernard Herrmann’s score to One Million BC, the movie with Victor Mature and Carole Landis—she committed suicide . . .”

But his comment as we listened to Symphony no. 4 had me curious. Did Coltrane listen to Vaughan Williams, too? “I don’t know,” he said. “But like Charlie Parker, he probably listened to everything.” Did Shorter ever meet Parker? “No, but I saw him about five times. I sneaked into a theater one time, when I was about fifteen. The fire escape, back of the theater, mezzanine, and there was Bird with strings, playing ‘Laura.’ I liked Bird with strings. The word was like, it’s a novelty, it won’t last, but Bird really wanted to work with the orchestra.”

Shorter said he had been looking at semiretirement, which meant less time on the road and more time thinking about composing music that would contain only a little of his playing—“not all over the place, just where it counts.” One such piece is “Aurora Leigh,” a composition which he started when he was eighteen and at NYU, named after an Elizabeth Barrett Browning poem; he said he might bring it to David Robertson, the principal conductor of the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, who wanted to work with him. Recently, he said, he had begun to work with the soprano Renée Fleming, writing original music for her to sing.

“When I listen to music, I’m not thinking about the workshop aspect of it,” he said. “ ‘Oh, that sound goes good against that one.’ Boring. But, you know, Elgar, who wrote something about people that he knew, characters he knew?” (He was describing The Enigma Variations.) “Each theme was antiphonal. You say, ‘Describe this person in music,’ and he’d do it, whether the person was rotund or skinny.

“I need to find out more about other people’s cultures, with the time I have left,” Shorter said, jumping over a conversational hedgerow. “Because when I’m writing something that sounds like my music . . . well, not my music, I don’t possess music—but when they say ‘Wayne Shorter’s playing those snake lines,’ I should take that willingness to do that, that desire I have to do that, and extend it to the desire to find out more about what is not easy to follow, what is difficult to follow in someone else’s life.”

I asked if he would like to hear one more piece of music.

“Do you think that would enhance what you’re writing, so people could hear through your words?” he asked, without really waiting for an answer. “I used to think, what the hell is music for?” Shorter mused. “Like, what is law for? Is it for immediate checks and balances and controls? But then what is it really for? And music—is it an aphrodisiac, a convincer, a manacle? You know, ‘I gotta have my rhythm and blues, man . . . ’ ”

What if I were to ask him if there was some piece of music, or some kind of music, that had altered his life in a positive way? How would he reply to that?

“Actually, music hasn’t changed my life; it’s the other way around. Somebody asked me that once, a young guy in Spain. He said, ‘What has life taught you?’ I said, wait a minute, think of it this way: what can you teach life?” He talked further about this “human revolutionary process,” then concluded: “For me to be aware of something that has great value, I change my life.”

I tried rephrasing the question. Is there music that embodies a value for which you would change your life?

“See, to me, the sound of music is neutral,” he returned. “What I do is arrange the dialogue, the musical dialogue, in a way that has not been spoken to me before.”

Does he often hear a piece of music and think that he hears himself represented in it?

“Oh, yeah. I used to play all kinds of records, and I’d get my clarinet and get right in it. One thing I liked about Charlie Parker: he’d play that song ‘South of the Border, Down Mexico Way.’ That’s a nice song. One of Gene Autry’s hit songs. Nothing complicated, but I like it.”

Set List

Ralph Vaughan Williams, The Complete Symphonies, conducted by Sir Adrian Boult, EMI boxed set, recorded 1967–75.