The Cuban pianist Bebo Valdés, a living repository of the glories of twentieth-century Cuban music, lives with his wife, Rose Marie, in a small ground-floor apartment in Brandbergen, Sweden, just outside of Stockholm. Around the place is an index to his remarkable life.

Valdés, tall and bold-featured, stands in a suit on the cover of a book published in Havana in the 1950s for the English-language market, Cha Cha Cha & Mambo for Small Dance Bands. The book sits on a shelf of well-thumbed sheet-music books: 100 of the Greatest Easy Listening Hits, the Beatles, and the two volumes of Joseph Schillinger’s System of Musical Composition books, the dense works valued by composers in the 1940s and ’50s that break down melody, harmony, and rhythm into mathematic logic. Paintings by Haitian artists hang on the walls. Other objects haven’t lived here as long: a Grammy and a key to the city of Madrid.

Slavery was abolished in Cuba in 1884. Bebo Valdés was born in 1918. His mother came from a Spanish family; his paternal grandfather was a slave. Afro-Cuban jazz is the ultimate mixture of African, European, and New World culture; as an example, it puts the batá, the two-headed drum of Yoruban religious music, alongside European harmony and American swing. But Valdés remembers a time when it was effectively prohibited to use the batá in a dance orchestra. He was the first to do so, in 1952.

That was at the club Tropicana, the biggest nightclub in Havana, where Valdés was the pianist in the house orchestra, during the height of the mambo’s popularity. I asked him how it had come about, to put the batá into dance music. He shrugged. “Roderico Neyra, the choreographer of the club,” he said, winding up, “had African-themed shows in November, December, January. He said, ‘Why don’t you write something that isn’t just all drums?’ It had been used orchestrally, in the symphonies of Obdulio Morales and Gilberto Valdés. But I was the first to use the batá in dance music.”

I knew a little about Gilberto Valdés as a distant historical figure. A classical-music composer, he presented Afro-Cuban-influenced compositions at Havana’s Municipal Theater in 1937, taking a stand against cultural prejudices. But Bebo Valdés—no relation to Gilberto—knew Gilberto Valdés as a person. “Gilberto Valdés was white, blond-haired and blue-eyed, and yet he was the best composer of African music around,” he marveled. “What’s the name of that American who wrote ‘Yesterdays’? Jerome Kern, right. He was like Jerome Kern.”

He turned to the piano, for the first of many demonstrations. “I want to explain a pentatonic scale,” he said. He played a full C-major scale and then omitted the fourth and seventh scale degrees, the F and the B, making it pentatonic. Then he used those notes to pick out the melody of Kern’s “Old Man River.” “I have forgotten some of this!” He laughed. “But that scale, that pentatonic scale, is based on African music.”

Bebo Valdés graduated from Havana’s Conservatorio Municipal in 1943. “It was the poor man’s conservatory, and the best,” he insisted. A gifted arranger, he worked with his hero, Ernesto Lecuona—probably the greatest Cuban composer of the century—toward the end of the older man’s life, in the mid-1940s.

Valdés was in the inner circle of musicians that developed the mambo, along with the multi-instrumentalist Orestes López and the bassist Israel “Cachao” López. At the Tropicana—where he was also musical adviser—he played with, or arranged music for, most of Cuba’s star singers and musicians, including Beny Moré (who sang for the club’s orchestra), Miguelito Valdés, and Chano Pozo. When Nat King Cole, a habitué of the Tropicana, came to Havana to record his Spanish-language record Cole Español, Bebo Valdés played the piano and arranged the album. He was a one-stop paragon of playing and arranging, the epicenter of a thriving world.

He had five children in Cuba, including Chucho Valdés, who has gone on to become one of the greatest pianists in the world. In 1960, after the revolution, Bebo Valdés fled the country—landing in Mexico, where he worked in television and in recording studios and arranged for bolero singers, such as the very popular Lucho Gatica. He then moved on to Spain, where he became music director for the record label Hispavox. At a stop in Stockholm on a European tour with a group called Lecuona’s Cuban Boys, he met and fell in love with Rose Marie Pehrson. He was forty-four and she was eighteen. He stuck around.

It was 1963. He would have liked to relocate to New York City, but his sister, who had moved there, warned him against the United States; he was, after all, a black man with a white wife. For a while he bided his time. He remembers being of the common opinion, while he was in Mexico, that Castro would not last three months.

But Valdés has never returned to Cuba. He stayed in Stockholm, starting a new family and playing piano in hotel lounges for more than thirty years. (Hence the easy-listening songbooks.) He has a working musician’s pride, and no regrets; he is happy with all that he knows.

In 1994, the Cuban jazz saxophonist Paquito D’Rivera called, inviting him to Germany, to work on a record together. It was to be a loose, jam-session record, but Valdés wanted structure. He orchestrated nine of his own songs for a nonet in two days. And it was going to be a D’Rivera record, but it ended up as Bebo Rides Again, his first record in three decades.

In 2000, he took part in Calle 54, Fernando Trueba’s documentary film about Latin jazz. Valdés’s imposing wisdom and the lightness of his demeanor gave his scenes, and the movie as a whole, a kind of magic lift. Trueba, not satisfied to close that chapter, formed a record label with the film-and-music historian Nat Chediak and made a series of records involving Valdés. One of them, Lágrimas Negras, a record of boleros by Valdés and the Spanish gypsy singer Diego El Cigala, sold nearly a million copies, mostly in Europe. In Madrid and Barcelona, particularly, crowds started to applaud him on the street.

Since then he has kept moving, making a run of albums including Bebo De Cuba, a double-disc that won a Grammy and a Latin Grammy in 2005; it included his original “Suite Havana.” He toured the world with Cigala in 2004 and played a sold-out week of duo shows with the bassist Javier Colina at the Village Vanguard in late 2005, at the age of eighty-seven. What a remarkable late chapter.

Valdés was to turn eighty-eight shortly after I visited him. I came to his house in Stockholm with Chediak, the producer for Calle 54 records, to whom Valdés has become extremely loyal. Valdés is cheerful and punctual—so much so that his tour with Cigala thoroughly stretched his patience. (Cigala tends not to show up on time.) He and Rose Marie live not far from their two Swedish-born sons, Rickard and Raymond, whom he dotes on.

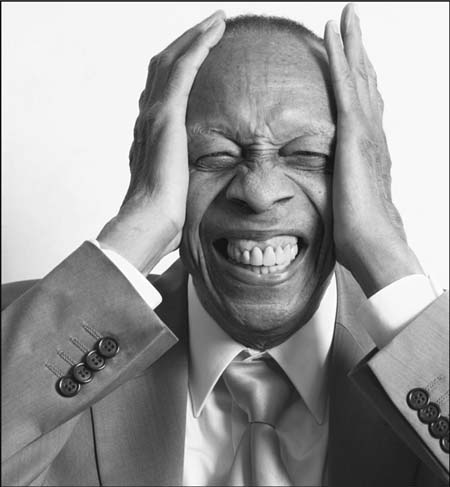

Valdés takes small steps, and moves quickly, especially toward his piano. He scoffed witheringly when asked about arthritis, and claimed to be never tired. (“And I’m not bragging,” he added.) He practices scales and arpeggios for thirty minutes daily and prefers to eat one meal, around lunchtime. He does not dance well and seems to take a kind of pride in this fact. He does not drink alcohol—though he noted that he would take a sip when “Lágrimas Negras” is certified a million sold—but takes in prodigious amounts of American coffee throughout the day.

He speaks mostly in Spanish, but with sprays of Swedish and English, depending on whom he’s talking to. (His son Rickard, who plays percussion in a Stockholm salsa band, finally learned Spanish in his midthirties.) His memory for names and dates is sharp, and for my visit, he prepared a precise list of music to listen to, each piece keyed to particular fascinations.

The first was his hero, Lecuona, who died in 1963. We heard Lecuona himself play “La Paloma,” which stitches two-beat and three-beat rhythms together; Lecuona plays it with pronounced rhythmic shifts. It has the beauty of the French formal dances that originally accompanied slave masters when they moved from Haiti to Cuba in the nineteenth century. “I first heard of Lecuona when I was in conservatory, in 1934,” he said. I asked if Lecuona’s music was taught in conservatories back when Valdés was a student. “Oh, no, no,” he said, surprised by the idea. “Only classical. Everything we learned in conservatory was before Cervantes.”

He was speaking of Ignacio Cervantes, the Cuban composer who died in 1905. A conversation with Valdés tends to go this way: an immersion in a full history of Cuban music, stretching from the days of Spanish rule, to Yoruban abakuá chants, to contradanzas to mambo to modern Latin jazz. At the mention of Cervantes’s name, he sat at the piano and performed all of Cervantes’s short “Danza No. 1.”

“One of Cervantes’s parents was German, and he was sent to Germany to study,” he said, on a tangent. “Entonces, he was Lecuona’s favorite. You can’t criticize Cervantes. He did wonderful things, but rhythmically, he copied Saumell.” (This reference was to Manuel Saumell Robredo, considered the father of Cuban contradanza.)

He played part of “Danza No. 1” again, emphasizing the five-note pattern called the cinquillo. “The cinquillo was present in the contradanza,” he explained, “and then Saumell Cubanized it, with Cuban melody and rhythm in the cinquillo. The blacks from the Antilles were the ones who took that rhythm to New Orleans. There are rhythms I’ve heard played at New Orleans funerals that I recall from the cabildos,” the African neighborhood associations in Cuba.

He got back to Lecuona. “You know who he reminds me of? My Chucho. He was a child prodigy, and he could really play from the age of four. There are passages there where he was playing bitonally—in two different tones—and I didn’t know that could be done at the time,” he said. “Really, he’s doing three things at the same time. The left hand plays the accompaniment, and the right hand the melody. On top of that, there’s a lot of improvising.”

Valdés appreciates difficulty. “He had a great left hand, and he wrote for it,” he said, returning to his piano and trying to play one of the lines in the music. “There are a lot of tenths in the music.” Valdés demonstrated, but suddenly he wasn’t playing Lecuona anymore; he was playing a boogie-woogie bass line with his left hand. “It’s very difficult to play boogie-woogie, too.”

Lecuona, he explained, developed his prodigious talents early, performing in public from the age of nine. “He was a great person, Ernesto, and a great musician. He had lots of women singing for him, students, and they all cooked for him, too. When he won a piano competition in Paris, in 1928, they asked him to play something of his own, and he played ‘La Comparsa.’ ” (It has become one of Cuba’s most famous songs.) “The ovation was enormous. With the money he made from winning the competition, he bought himself a farm which he called ‘La Comparsa.’ ”

Valdés started reminiscing again. “A man told me once that Lecuona could be the world’s greatest pianist when he was in good spirits, but when he was in a bad mood, or had some kind of problem, he could be the absolute worst.”

Was it just his mood—not drinking, or anything like that?

“Oh, no, he didn’t drink,” Valdés said, waving a big hand. “Just coffee. He smoked a lot of cigarettes, and his fingers were all yellow from nicotine. But he didn’t eat much, and he was asthmatic.

“I think maybe it’s spiritual,” he mused. “When we were filming Calle 54, I didn’t know what to play. So I played ‘La Comparsa,’ and a lot of people say it’s their favorite tune in the movie.”

We moved on to Art Tatum. “My favorite pianist!” he boomed. “He and Bill Evans.” He played Evans’s “Waltz for Debby,” complete with a full chorus of rigorous improvisation. “I love to improvise,” he said.

Turning back to Tatum, we listened to “Without a Song,” Tatum solo, from the 1955 recordings made at a private party in Beverly Hills. It is rhapsodic, with tremendous, crashing, full-keyboard runs—always through appropriate chord changes—functioning as stepping-stones. “It’s virtuosic in technique—totally classical, with modern harmony,” he said. “He was the first pianist I ever heard playing modern harmonies and playing them with heart. The runs he plays without ever making a mistake—and on top of that, he was blind! The first pianist I ever listened to in American music was Eddy Duchin,” he noted, picking out a little bit of “Heart and Soul.” “But when I heard Tatum, he wiped out everyone.”

Tatum had a kind of orchestral idea for the piano, I suggested. He was everything at once. Valdés disagreed. He understands the word orchestral to mean sealed off to improvisation. “But he never played rhythmically,” he said, meaning he never played in straight, fixed rhythm. “He was always improvising. He would change time signatures, put one harmony on top of another. I try to imitate him at times, but who am I?”

In the 1940s, Valdés wrote a piece called “Oleaje.” It was included on Bebo Rides Again, his comeback album; it is also near the end of Bebo, his carefully pedagogical solo record of songs by Cuban composers that covers nearly two hundred years. He wrote it thinking of Tatum and his wide, arpeggiated flourishes.

I don’t think Tatum ever made it to Cuba, I said. “No,” he said. “I also know that he died in 1956.” (He was right.) Yet Valdés heard lots of Tatum records in Cuba. “There was a constant flow from America to Cuba,” he explained. “Americans used to buy summer homes and retirement homes in Cuba. Sinatra and all those guys used to go there all the time. A lot of the places I played were American owned—mafia or no mafia. It was almost like a colony.”

When Valdés was solidifying his reputation in Cuba, several compatriot musicians were reorienting jazz in New York City. (He never spent time there; the only possible American visa available to him was for twenty-nine days, and he wasn’t interested in such a short stay.) Mario Bauzá, who had left Cuba in 1930, became enormously influential to Dizzy Gillespie. In 1947, Gillespie’s big band was joined by Chano Pozo, who drilled the band in how to play Cuban grooves, particularly the tumbao, the repeated bass pattern. (It was a new combination for everyone; even in Cuba, big bands were only beginning to use congas.) The great document of this period is the song “Manteca,” a hit record for Gillespie.

Valdés believes that Gillespie’s American band played the Cuban rhythms perfectly. He put the track on. “I really hear the conga and the changes in the bass. And the part going boom-BAH, boom-BAH”—he imitated the baritone saxophone—“that’s all the tumbao of mambo,” he said. “It’s completely the mambo style of Cachao.” The song lifted out of Cuban rhythm and into swing, with more arranged harmony, and he savored the shift. “Yeah!” he yelled, enjoying the swing rhythm just as much.

Right after this, he put on a Frank Sinatra record from 1960, “Nice ’n’ Easy,” arranged by Nelson Riddle. It has the easy midtempo bounce of Sinatra records at the time, and this thrilled Valdés. “Nobody can play music like that except in America, that kind of swing, that time,” he said. “It’s impeccable. The most difficult thing in the world is to play slowly and keep time. When I listen to this, I see American black people dancing.”

Was Sinatra known to listen to Cuban bands a lot?

“Yes,” he said, with certainty.

So what’s the secret Cuban influence in a record like this?

“I think it’s really an Italian influence,” he said, laughing. “No, it’s just that a lot of things that are called American really come from the Antilles. Like his incredible sense of swing. Yet America, from the thirties to the fifties, gave a lot of music to the world, of which we are all the children. Even though I’m Cuban, I’m really an American arranger,” he reflected. “Because the way I write has as much to do with American music as it does with Cuban music. And at the same time it has to do with the fugue.” (An example of his fugue writing comes in the middle of “Devoción,” part of his “Suite Cubana.”)

Chediak pointed out that fugues have little to do with Cuban or American music. “Yes, but I do it anyway,” said Valdés. “Why shouldn’t I, if I know how?”

We broke for lunch. Valdés puttered around nonstop in the kitchen, bringing out ham and tomato sandwiches, coffee, fruit. He refused to sit down. When we were finished, he brought out the sheet music to Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto no. 2 in C Minor, to use as a reference as we listened to it.

“I was studying composition and harmony when I heard this performed by the Havana Symphony, in the forties,” he said.

What he wanted to show was how the composer can build up a beautiful, fragile melody, then protect it as the orchestra swells around it. “When I hear the music build to a crescendo, I feel like crying,” he said.

I asked whether he was able to use this device in his own arranging. “Whenever I can get away with it!” he said. He put on the guajira section of the “Suite Cubana,” called “Copla no. 4,” to demonstrate. It has the same effect: big, brass-heavy crescendos, building in intensifying shades and colors around the melody.

“When you know classical music, you can do what you want to do,” he said, and then recited an old maxim to indicate that he had succeeded on his own terms: “Es mejor ser la cabeza de un perro que la cola de un tiburón.” It’s better to be the head of a dog than the tail of a shark.

Set List

Ernesto Lecuona, “La Paloma,” from The Ultimate Collection—Lecuona (RCA), recorded 1928.

Art Tatum, “Without a Song,” from 20th Century Piano Genius (Verve), recorded 1955.

Dizzy Gillespie, “Manteca,” from Dizzy Gillespie: The Complete RCA Victor Recordings: 1937–1949 (RCA), recorded 1947.

Frank Sinatra, “Nice ’n’ Easy,” from Nice ’n’ Easy (Capitol), recorded 1960.

Sergei Rachmaninoff, Piano Concerto no. 2 in C Minor, Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Vladimir Ashkenazy, piano; London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by André Previn (Universal/Penguin Classics), released 1990.