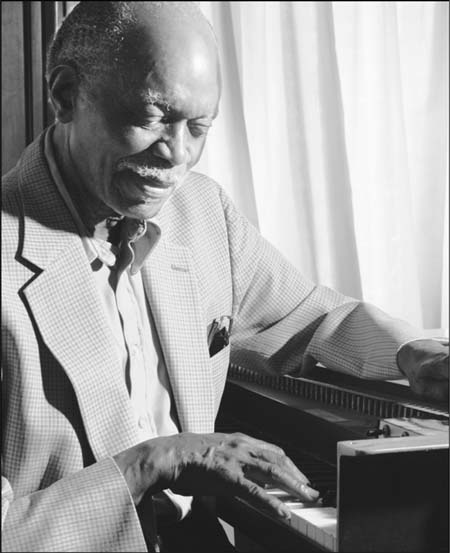

The last sixty years of jazz seems to be retained in the pianist Hank Jones’s head: a labor history of all the jam-session, studio, one-night, and concert-hall gigs he has played since moving to New York City in 1944. Jones has been one of the hardest and most consistent workers in the history of jazz. As a result, his focused, organized, subtle touch—one of his devices is to turn up the energy of his improvising while still playing softly—shows up repeatedly in any accounting of the music.

The recorded history of Jones’s playing begins with a Hot Lips Page session in 1944 and then works through Charlie Parker and Billy Eckstine and Artie Shaw and Ella Fitzgerald. It gets a bit obscure in the 1960s—Jones was working as a staff musician at CBS from 1955 to 1972—but becomes fully trackable again in the mid-1970s, with a serious renewal of his trio playing.

Unlike Oscar Peterson, he never had a Norman Granz to keep his career consistent and to control the flow and quality of his recordings. Since the 1970s, his discography has become a bramble; no other jazz musician of his stature has made so many records for so many labels, some of them great, others homely or compromised or badly conceived. Once I saw him play a gig in a senseless trio, set up by a record producer, with Omar Hakim, the loud-and-bland fusion drummer. It was like a Ford Escalade against a loom, or a watchmaker’s lathe. I know I’m mixing metaphors; the performance did that, too. But he rolled on unperturbed, retaining his professionalism.

When I got together with Jones in 2005, he was having a stout year: working in Joe Lovano’s spectacular quartet, with the bassist George Mraz and the drummer Paul Motian, and getting ready to release a new trio record, For My Father, under his own name, at age eighty-seven. After all these years, Jones plays as if hitting the highest level of small-group jazz playing were as easy as walking. He has the sound of wisdom.

Jones rarely listens to jazz at his home in Hartwick, New York, near Cooperstown, where he lives with his wife, Theodosia. When he isn’t working, he prefers to practice, two to four hours a day, rather than hear anyone else’s music. What’s the point of accepting a mediated version of jazz, when you can trace its family tree through your own life and work? (If you had been around Nat King Cole as a fellow musician, as Jones was, and heard him play at his best in jam sessions, Nat King Cole records might sound to you like contrivances.) Anyway, Jones likes to keep his focus on what is to be done tomorrow.

In his gracious way, Jones posed a challenge to my project. He stalled at step one: given the assignment, to which he quickly agreed, he had a Bartleby-like resistance toward choosing any music in particular.

“I’m really not much of a listener,” he explained in a preliminary phone conversation. We isolated a few areas of interest, including solo style, small-group arrangement, unaccompanied piano, and pianists backing up singers. Beyond that, he left it up to me.

He had one other desire, though: “I’d like to choose something by Count Basie,” he said. “Because everything he did was so unpretentious.”

We met at a hotel room in midtown Manhattan one evening, during one of his visits to the city for meetings and rehearsals. His day’s work was done, but he greeted me in a coat and tie. Jones spoke rapidly, with a melodious roll in his voice; when forming an opinion, his eyes flashed. Records may not mean much to him per se, but when zeroing in on individual performances, he was an astute, original thinker.

When Jones was a young musician working in Detroit during the late 1930s and early ’40s, Art Tatum was important to him, along with Teddy Wilson, Fats Waller, and Earl Hines. “They represented a level I was trying to attain,” he said. “Trying to attain. I’m not saying I ever attained that level, but you keep trying. It’s a never-ending process.”

Talking about his strivings as a pianist, or about his betters, he adopted a different tone. He never lost focus and became resigned or defeated; on the contrary, he grew factual and energized. And Tatum was the one pianist Jones talked about most as a paradigm, though a conceptual one rather than a practical one.

“As far as Tatum is concerned, it may take a few hundred years before I can get there,” he said. “I don’t want to play exactly like Tatum. I’d like to adapt some of his technical ideas, but as far as imitating him note for note, I don’t think that’s good for anybody. I’ve heard pianists who can play Tatum’s solos, or at least that’s how it sounds. But there’s one thing about creativity. You can do that with classical pieces, even the most difficult—you can play them note-for-note, the way the composer wrote them, right? Or you could play Tatum’s solos, if you had the technique. But the inventiveness, the creativity, is not there.

“It’s one thing to interpret, in other words, and it’s another thing to create,” he concluded. “Tatum did both simultaneously: creative and interpretive. Simultaneous composition, you might say.”

Jones first heard Tatum in the late 1930s, at his family home in Pontiac, Michigan, on a radio broadcast from Detroit. (By 2005, he was the last survivor of ten siblings, who included two other superior musicians: the drummer Elvin Jones and the trumpeter Thad Jones.) Then, he was convinced that the Tatum broadcast was actually two pianists, with the gimmick of sounding like a single, invincible one. Later, after moving east, he finally saw Tatum in Buffalo, where Jones’s band was working at the Anchor Bar, and Tatum was at McVan’s, across town. Jones watched Tatum each night after work. “Funny thing is, he was playing on a piano which wasn’t a grand; it was a spinet,” Jones said. “But he made it sound like a Steinway D.”

I chose a solo performance of “Sweet Lorraine” from Tatum’s 1955 private-party recordings in Los Angeles. Jones had heard the recordings, but it had been a while; though he didn’t anticipate the details, he quickly picked up on them, as if they pricked his memory. Before the first bridge, Jones started chuckling; in the bridge, Tatum dislodges a titanic, disruptive run, a microcomposition in itself, referring to the song’s chords along the way. Then, for comic effect, he quotes the melody of “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen.” Jones laughed again.

“One of the most impressive things is, of course, those runs,” he said, “which he played at blinding speed with either hand, and he sort of set up the next chord progression with them. And the run itself is, of course, a chord progression; you can hear the chords in there. A lot of people say, ‘Why does he play all those runs?’ Well, they’re an integral part of his style.”

So what a lot of people take as exclamation points, or pure ornament, was really functional for Tatum, a means of binding all the action together? “In a sense they’re exclamation points,” Jones said. “It’s like we’re having a conversation, and the runs illustrate where he’s going, or maybe illustrate that part of the melodic harmonization or harmonic progression that he’s using. Melodic, harmonic; they’re interchangeable. They’re not separate; they’re part of a whole. He integrated everything so well that you can’t separate any one part from another.

“But without the runs, what he was doing would probably not be as effective. He made a lot of excursions. He’d spot a progression, and on the way there, he takes a little excursion and plays a run to illustrate his point; maybe he’s describing something that he saw on the way there and on the way back,” he said. “His playing is very descriptive, you know.”

We listened to it again, starting from the beginning. “He definitely shows you parts of the melody,” Jones said, during Tatum’s introduction. “Now here he goes,” he said, at the obvious beginning of the melody proper. The first real explosion of technique went off during the bridge and startled Jones. “His playing is almost beyond description!” he said.

At the end of one chorus, as it led into the next, Tatum’s run set up the harmonic motion to follow. During the longest, most percussive run in the performance, Jones’s face lit up. “You see? He’s changing chords with every beat of that run.”

Another bridge came along, with another excursion. “Everything he does is a concerto,” Jones said, wonderingly. “He knows exactly what he’s doing.”

I asked Jones who else impressed him when he was working in Detroit. “There wasn’t a lot of great music being played,” he said. “They had a lot of studio bands, radio bands, and there was one guy, Bill Stegmeyer, who later became one of the writers for The Jackie Gleason Show, an excellent arranger—he was working with one of those bands. He was an excellent teacher, by the way. I studied with him later.” Jones studied classical piano repertory, especially Chopin, with private teachers into his fifties. “And there was a pianist named Lannie Scott, who had a style similar to Art Tatum’s. Both Lannie and Art had a trick where they’d play ‘Tea for Two’ with the left hand and smoke a cigarette with the right.”

Jones left Detroit for Cleveland in 1942, working at the Cedar Gardens nightclub, where there were also dancing girls and a comedian. On Sunday afternoons, he said, a fight routinely broke out in the middle of Cedar Street, near the club’s front door. “I think a lot of people came just to see the fight,” he noted dryly. “It was very interesting.”

Subsequently, he took the gig in Buffalo, where he first saw Tatum, and then moved on to New York City. He deposited his Detroit union card at the New York Musicians’ Union, Local 802, and played a series of pickup gigs while waiting the requisite six months before landing an extended job—a rule back then, to limit the bulging union rolls. Then, at the invitation of the saxophonist Lucky Thompson, he joined Hot Lips Page’s big band, first at the Onyx Club on Fifty-second Street and then on tour.

“We went out on the road, doing three months of onenighters,” Jones remembered. “And I learned a very valuable lesson at that time. Which was: never do that again.”

We pushed on to Count Basie, another of his models. “The thing about Basie, which to me is very significant, is that the band was the main focus,” Jones recalled. “He played maybe only an eight-bar or twelve-bar or thirty-two-bar solo. He integrated his style into the big band, which was usually a single-finger style—although I heard him play stride piano, by the way, and he was also a great organist. In a big band you play a lot less, because you have to play in the spots, and that has to relate to the whole. I think he used taste in the best possible way, you know. By not overplaying, and yet being effective. That’s very difficult to do—to play minimally and yet have a maximum effect.”

We heard “Time Out,” from 1937. Jones didn’t recall the title but recognized the song after a few seconds. Each player in the Basie band contributes an equal share to the total sound, with slangy phrasing and a deep, relaxed groove. It’s a spacious, natural record. Soloing, Basie starts out with his usual edited phrases, then begins a stride passage and grows more voluble. “Oh?” Jones said at that point, cocking his head and listening hard.

“I heard a certain amount of discipline there,” he said, when the song ended. “Duke Ellington had a great band, but it didn’t have that kind of discipline, in my estimation. Duke wrote a lot of great music. It’s just that when the reed section was playing, you heard a lot of Johnny Hodges, but not a lot of the other horn players.”

Starting in 1947, Jones played with Ella Fitzgerald in Norman Granz’s Jazz at the Philharmonic concerts. (While many of his colleagues drank or gambled, Jones said, he read novels and practiced the piano.) During this period he developed an admiration for Jimmy Jones—no relation—who became Sarah Vaughan’s regular accompanist in the 1950s. (Jones himself didn’t work much with Vaughan: only two concerts and a record date.)

He wanted to hear something by that pair, and because he wouldn’t put his finger on anything in particular, I chose Vaughan’s “Embraceable You,” from 1954. It’s among the best-known things they did together, but it has a fairly sleepy tempo.

He listened as Jimmy Jones played chords softly, on every beat, under Vaughan. “Jimmy’s accompaniment on this particular tune isn’t typical of what he could do,” he quickly decided. “This is fairly subdued; he’s providing a harmonic background, not interfering with her. But I’ve heard him play accompaniment that, to me, sounded as if he were thinking along the lines of Ravel.”

He elaborated a little. “Here he’s using what I think of as a continuous style. He’s not playing just on fills. He’s using a melodic foundation behind her, which is continuous, almost like a counter-melody.” Suddenly Jimmy Jones picked out five treble-clef notes, a short, original fill, just before Vaughan sang the line “Come to Mama, do.”

“Now, I think Sarah liked those kind of fills,” Jones said. “Singleline fills. In my estimation, if you do that, you run the risk of interfering with the singer’s train of thought. But I think Sarah liked the pianist to lead the train of thought and for her to follow. Ella’s preference was for block-chord fills, to make her feel comfortable—never leading, always playing in response to her.”

Jones’s next request was Charlie Parker, who fit into the same category as Tatum—a virtuosic, fascinating soloist—but whose music also qualifies as great small-band music. (Jones recorded with Bird in the early 1950s.)

I chose “Ah-Leu-Cha,” which Jones surprisingly said he didn’t recognize, from a 1948 recording. “Perfect control,” Jones muttered during Bird’s first solo, with its clean, strong sound even through double-time runs. “He always had that beautiful tone. And he never played extended solos, maybe two choruses, but that would be all you wanted to hear.”

The song banged shut, and Jones laughed again. “Bird would play a thirty-two-bar song, and then he’d play a blues, but he always had that same kind of tone,” he said. “That’s what makes him distinctive. I think his tone is equally distinctive as his style. They go together. Without the tone, the style wouldn’t be as impressive.”

What did Parker want from a pianist in his groups? “He required a pianist to follow the chord changes correctly, and not to overplay but just play in spots,” Jones said. “Bud Powell did that; Al Haig did it. Anyway, if you didn’t listen for a while, you wouldn’t know what he was doing. You had to listen to find out what direction he was going in, and you played the fills accordingly.

“Working with Charlie was quite an experience. You always heard something that made you think, and think in the idiom that he was playing in. He’d pull you along with him; you couldn’t just play your own way. He’d get you used to the idea of getting outside of yourself, because that’s what you have to do.”

Jones is one of the few leading musicians left from the early bebop era who can comment on what the greatest players were actually thinking about the new music.

“At that time,” he said, “a lot of musicians put that style down. They didn’t like it. You’d think that musicians would be the first ones to pick up on it, but a lot of them didn’t—‘What are these guys doing?’ I didn’t think that at all. My ears were wide open; my brain was receptive. I thought it was a change for the better, harmonically and melodically. It was a very difficult style to learn to play, and it still is. I don’t consider myself a master of the style. I consider myself a student of it.”

Starting in the late 1950s, Jones had been willing to sacrifice much of what many might consider an artistic life for his steady job doing live radio and television with CBS. He lived then in Cresskill, New Jersey, just across the Hudson River and slightly north of Manhattan, and he couldn’t leave the area. “You were always subject to get a call from the contractor for an unexpected rehearsal, so you had to be on the scene,” he explained. “It would be four or five, and they’d call and say, ‘Can you be here at six o’clock?’ This is a.m., mind you.”

He worked five days a week and was assigned to a round-robin of variety shows: Ed Sullivan, Jackie Gleason, Garry Moore. He played on two live radio programs—one Dixieland, one modern jazz. He played rehearsals. “I liked the challenge,” he said. “Every week there was a different challenge—some kind of sight-reading or adapting to a different style. And of course it was a substantial income; basically it was a year-round job, and it had a pension and health insurance. If you went on the road, you might do well for one tour, but then you might be out of work for six months. Well, that’s no good,” he said, shaking his head. “Mortgage payments have to be paid.”

At this point in our conversation Jones didn’t really seem like most of the jazz musicians I know, with their aristocratic pessimism and stubborn aesthetic ideals. Both in his listening and in his bits of autobiography, he reminded me of some other kind of highly refined worker-for-hire: a craftsman with an old-fashioned work ethic, someone sanguine to the truth that he won’t be making masterpieces on someone else’s clock, but who proudly delivers on time.

I asked if it was even possible, back in the CBS days, to stay up late at jazz clubs. “Well, that’s why I had to stop working at the Vanguard,” Jones said. (One of the jazz-club jobs he briefly tried to pursue during that time, starting in 1965, was as the pianist with the great, transformative big band led by his brother Thad and the drummer Mel Lewis; they had a regular Monday-night gig at the Village Vanguard.) “They would get out of work at two-thirty, but I had a seven o’clock rehearsal with Jackie Gleason.”

“I know I can do better than I’m doing now,” he commented, casually, toward the end of our talk.

You really mean that?

“Oh, yeah. There’s another level that’s reachable. I think it’s just a question of time, perhaps, or dedication. I know it’s there.”

Do you know what it sounds like?

“What you do is imagine what it should sound like,” he explained. “Once, I was working on Fifty-second Street with the Coleman Hawkins group. In the group was Max Roach, Miles Davis, and Curley Russell was the bass player.” (Jones reckoned this was around 1954. But it must have been 1946 or 1947, when Hawkins, an elder figure, was making a point of playing with the first wave of bebop musicians.) “I was living up on 101st and Madison, and I used to go to work every night on the bus. On this particular night I was a little bit late.

“When I walked in and started playing, I played things that I had not played before. It may have been caused by stress; I don’t know what caused it. But I was on a different level at that time. That may sound a little screwball, but that’s what happened. You can think thoughts you haven’t thought previously.

“I think people like Charlie Parker could do it consciously.” He laughed. “I’ve got to do it subconsciously.”

This was steadying to hear. Lateness, mysterious higher levels of accomplishment, the subconscious—now he was sounding very much like a jazz musician.

Art Tatum, “Sweet Lorraine,” from 20th Century Piano Genius (Verve), recorded 1955.

Count Basie, “Time Out,” from The Complete Decca Recordings (Verve), recorded 1937.

Sarah Vaughan, “Embraceable You,” from Sarah Vaughan with Clifford Brown (Polygram), recorded 1954.

Charlie Parker, “Ah-Leu-Cha,” from Best of the Complete Savoy and Dial Studio Recordings (Savoy Jazz), recorded 1948.