On the wall of his wood-paneled basement in suburban Long Island, the drummer Roy Haynes has hung a large poster of his idol, the Count Basie band drummer Jo Jones. In the picture, taken in 1940 in Quincy, Massachusetts, Jones stands outside of a building in a hat, suit, and full-length overcoat, holding a cymbal with his left hand and a brush with his right. The attitude is casual defiance: Jones’s feet are spaced apart; his chin and his eyebrows are raised. “He was the man,” Haynes said. “And he carried himself like that.”

In the summer of 2004 Haynes invited four other drummers to his house in Baldwin, New York, where he lives alone. Haynes, Eddie Locke, Ben Riley, Louis Hayes, and Jackie Williams ended up standing around the picture, drinking champagne and talking about Papa Jo. Likewise, a year later, when I showed up at Haynes’s house to talk about music with him, the conversation kept turning back to Jones.

Jonathan Jones, who died in 1985, made the high hat significant in articulating jazz rhythm, and it has ever been thus. He played authoritatively with brushes, not just on ballads. He snapped down his patterns with subtlety and force; he plowed powerful grooves for a band. He didn’t get involved in long solos; above all, he had vitality, magnetism. You could learn just by watching him move around. He was confident and inspired some fear. He was proud of his “kiddies,” the musicians he influenced. (He became known as Papa Jo in the late 1950s, in part to distinguish him from Philly Joe Jones, Miles Davis’s drummer.) Toward the end of his life, he liked to perform sections of concerts on the high hat alone.

Haynes never took a lesson from Jones. But he developed a whole area of technique around the high hat, treating it as an instrument unto itself, building on Jones’s principles. Really, he isolates every part of his drum kit in a similar way, letting it sing. He is attention-seeking, breaking up time, making his drum set react, hitting hard, and then leaving space. And he is naturally modern. During our conversation he kept reminding me of his breadth, that his sound must not be too quickly understood, that he plays in many different ways.

But a musician is not only what he plays. Jones approved of Haynes for his self-possession, too. Haynes bought his first car in the summer of 1950, the same week Miles Davis did. “Young jazz musicians buying cars was not heard of,” he said, proudly. “Let alone a supposed bebop drummer.” When I spent time with Haynes, he was eighty, and he owned four. One was a Bricklin, a rare machine with gull-wing doors, manufactured for only two years in the mid-1970s.

Haynes likes some crackle in his leisure. When he comes into Manhattan and he’s not working, he said, he often rents a limousine. “I’m like a little kid. I’m so excited, man. I just party, enjoy.” Though he doesn’t particularly like gambling, he bought a second house in Las Vegas in 2001; he travels there every few months and goes out to clubs and restaurants with his friends. “I used to play Vegas when I was with Sarah Vaughan, when there was still prejudice. I never thought I’d buy property there.”

And the clothes. He often cites his inclusion in a list, created by Esquire magazine in 1960, of the best-dressed men in America. A musician in his thirties told me he met Haynes one night at the Village Vanguard. He mentioned to Haynes that he had just played there himself. “I was wearing jeans and a flannel shirt, and my hair was dirty,” the younger musician recalled. “Roy just looked me up and down. And then up, and then down again. He said, ‘Huh.’ ”

Jo Jones was the obvious place to start, and our other subjects flowed from him. At the top of Haynes’s list was Count Basie’s “The World Is Mad,” from 1940, with Jones on drums. But since all CDs that include it have gone out of print, I brought instead a Basie box set called America’s #1 Band! since it covers that same period of the band.

We listened to “Swing, Brother, Swing,” which is about as good as American music gets. It comes from a radio broadcast in June 1937, recorded at New York’s Savoy Ballroom; it is the Basie orchestra with Jo Jones on drums and Billie Holiday singing. The groove is vicious, menacing; as the band restrains itself for the first chorus and then gradually turns it on, the guitarist Freddie Green drives the rhythm, chunk-chunk-chunk, and Holiday phrases way behind the beat.

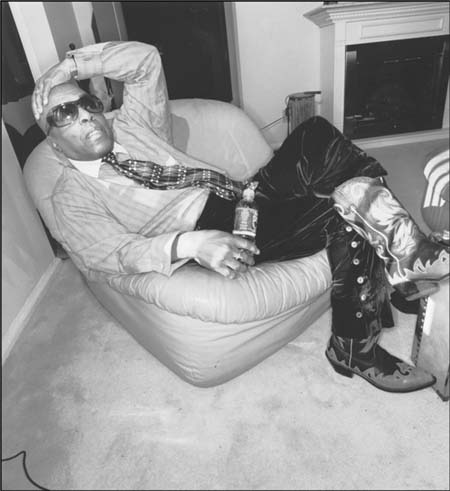

“Ra-rin to go, and there ain’t nobody gonna hold me down,” she sings. Haynes, wearing velvet pants and cowboy boots, sat on his living-room sofa and crouched close to the speaker to hear the details. “Can I hear that little part again?” he said. “I thought I heard a cowbell.”

He did. Jones hits the cowbell three times at the start of the second chorus, linking the bars together. From that point the band surges a little, makes the song meaner. “Aaah-haaa!” Haynes hollered.

“That’s a hell of a one to start with, man,” said Haynes, shaking his head. “If anybody wants to know what swing is, check that out. Everybody’s in the pocket. You know, you just feel it: I see people dancing.”

Haynes played with three masterful singers: Sarah Vaughan, Ella Fitzgerald, and Billie Holiday. His time with Holiday came during her last run at a club—Storyville, in Boston, in 1959. Late Holiday is different. It communicates frailty; it’s not rhythmically invincible, like this. “But there were still nights when some of that feeling was there,” he said. (It’s true; on the surviving radio broadcasts of Holiday’s shows from that week, you can hear him help to trigger that feeling with his drumming.)

He was born in Roxbury, Massachusetts. His parents had moved from Barbados, and his father had a job at Standard Oil. There were a lot of jazz bands in Boston but, according to Haynes, few good drummers. One of them, Herbert Wright, lived across the way from the Haynes house, on Haskins Street. He played drums with James Reese Europe and gave Haynes a few lessons in playing paradiddles. (Later, he earned the distinction of reportedly stabbing Europe to death in a fight.)

Haynes grew up among four smart, accomplished brothers. One was Michael Haynes, who has been a pastor at Roxbury’s Twelfth Baptist Church since 1964, in addition to serving as a Massachusetts state representative from 1965 to 1970. Michael was close to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., befriending him while King was studying for his doctorate in Boston. Another brother was C. Vincent Haynes, a photographer and writer, who died in 2002.

His brother Douglas Haynes was a trumpet player who attended the New England Conservatory of Music after serving in the army; he traveled to New York City when Roy was still in high school, and came to know musicians socially at the Savoy Ballroom. He introduced Roy to a number of them, including Papa Jo Jones, one night at the Southland Café, before Haynes left Boston in 1945 to work in New York himself.

Haynes’s next choice was “Queer Street,” again by Basie. “There was a White Castle, a hamburger joint, on Broadway and Forty-seventh Street,” he remembered, as the song played. “They had a jukebox there. I would put dimes in, and keep playing it over and over.” What he wanted to hear, he said, was Shadow Wilson’s complicated two-bar fill on the snare drum near the end of the song.

The tune is sharp Harlem-ballroom swing from right after the war—1946—with huge dynamic shifts and a deep four-four bass line. During the last fifteen seconds of the three-minute piece, Wilson comes in, playing double-time drum rolls and then turning his beat around. “Ohh, that’s it,” Haynes said, looking happy, and momentarily dazed. “Man, that’s something. Like I’m twenty years old listening to that.”

Wilson later played, off and on, in a short-lived quartet with Thelonious Monk and John Coltrane, the group that famously occupied the Five Spot Café for the second half of 1957, when Coltrane began to realize his own potential. “But I took him as a big-band drummer,” Haynes said.

“At one point, I was with Luis Russell,” he remembered. (This would have been in the mid-1940s.) “We were playing in Detroit, and Illinois Jacquet was in town, too.” After the gig, the Russell band went to see Jacquet, who was a star then. “I was good for sitting in with anyone I wanted to, mainly saxophone players,” he said. “I was known to be able to swing. Anyway, Shadow Wilson was the drummer that night. Shadow must have called on me, because I wouldn’t have asked him to let me sit in—I don’t think I was that game. But I went and played, and Jacquet didn’t know. When he turned around, it was me. He often talked about that. Because”—he hissed—“Shadow could swing. He didn’t have to play no solo.

“And I sort of fell into that category, too,” he added, with an if-I-do-say-so-myself tone. “I was known to be able to swing. That’s one of the things that I’m sure carried me in this business this long—having that thing. I talked to my grandson about it.”

Haynes’s grandson, the son of his daughter Leslie, is the drummer Marcus Gilmore—now in his early twenties, but a knockout musician even at eighteen. In some ways, Haynes sees his life relived in his grandson’s. Gilmore was born in a house in Queens that Haynes had bought. While studying at the Manhattan School of Music, he lived in a Morningside Heights dorm building next door to where Haynes lived when he played with Charlie Parker in the 1950s. And as Haynes was in the 1950s and ’60s, Gilmore is a stylebook of outward and sophisticated new jazz drumming.

What are the drummers from Marcus’s generation doing differently from those of yours? I asked Haynes.

“Oh, they’re doing a lot of stuff different,” he said.

But what? I pressed. For instance, in the 1940s and ’50s, there was a bottom-line responsibility to swing hard. Is that still as important as it was?

“That’s a funny word. What did you just say?”

“No, what did you just say after that?”

To swing hard.

“No, it wasn’t necessarily to swing hard. I was with Stan Getz for a while, and you know, it wasn’t particularly hard swinging. Sarah, for five years. We did some big-band stuff, too, but it was light. A lot of it was just mellow swinging. I played with Lennie Tristano and Lester Young, who were not exactly hard swingers. Though there were nights,” he considered. “I would say Art Blakey would be more hard. And Elvin Jones maybe would be more hard. So I did that if the situation called for it.”

That matter defused, he answered the original question. “But what are they doing different now? Mmm, they’re studying more, to start with, whereas people like myself, most of our studying was on the bandstand. And drummers now—not only drummers but players in general—they talk. There’s more talk, discussing what they’re doing and how they do what they do—theory. There are more drummers today than there were during the period when I was coming up, the forties and fifties. I don’t know what I would do if I was just a youngster coming up now. Even sometimes when you go to Europe now, they’re becoming more Americanized; they want to do the same type of thing that’s being done here.”

Max Roach was born two years before Haynes; they were important drummers in bebop’s first wave. “When I heard Max the first time,” Haynes recalled, “I said to myself, ‘He loves Jo Jones too.’ ”

We listened to Coleman Hawkins’s recording from February 1944 of “Woody’n You,” written by Dizzy Gillespie. It is considered the first bebop recording session. Gillespie is in the group, and Max Roach is the drummer. “I was impressed,” he said about Roach. “It was like he was talking to me.”

Haynes especially identified one detail: as Hawkins finishes his first solo in “Woody’n You,” Roach makes the final beat of the bar part of a figure that enjoins the bar with the next, and also the next chorus of the song. It sounds like one TWO three FOUR ONE BOOM three FOUR one TWO three FOUR. It breaks up the flow of time; it creates tension, and it stabilizes, too. Later in the song, during a trumpet solo, Roach thuds the bass drum, creating a single offbeat palpitation in the middle of a bar. “There,” Haynes said.

Bebop was just beginning to take over then, and Haynes stood at the middle of it. He saw some older musicians’ dissatisfaction with the way jazz was changing then—becoming more melodically fractured, more staccato, more drum-centered. Roy Eldridge was one, he remembered.

But from 1947 to 1949, Haynes played with Lester Young, the paradigmatic soloist of the period before bebop, and had no problem. “I had heard Lester didn’t like people getting too involved,” he said. “But he liked the way I was getting involved. I was dancing with him from up here,” he said, holding his hand up at the level of his head—meaning the ride cymbal. “I was doing stuff with my left hand and right foot, too, but I was always feeding him that thing from up there. I was swinging with him. And the word that you used earlier—hard—it wasn’t particularly hard. We were moving, you know, trying to paint a picture.”

He did something similar with John Coltrane, when he filled in for Elvin Jones in the John Coltrane Quartet in 1961 and 1963. After you become used to Jones’s drumming in the Coltrane group, hearing Haynes is a big difference; since the emphasis pulls away from the bass drum and toward the snare and cymbals, you can hear the bass and piano more.

Despite his protests against being known as a hard-swinging drummer, Haynes has always been a forceful one. I wondered whether each time he started with some new bandleader during those early years—whether Miles Davis, Charlie Parker, Kai Winding, or whoever else—he felt an instinct to see how much he could get away with, musically, before they started pushing back or objecting.

“No, I didn’t think that way at all,” he said. “Whoever I was playing with, I think they probably wanted me for what I was trying to do.”

The photographer Lee Friedlander, who visited Haynes with me that day, asked him if he knew a ten-inch instructional record from the 1940s by Baby Dodds, the early New Orleans jazz drummer.

“Yeah, man.” Haynes smiled. “I used to travel with that record.”

The record contains “Playing for the Benefit of the Band,” a wise and trenchant lecture. In it, Dodds says:

Anybody can beat a drum, but anybody can’t drum. You must study those things—study a guy’s human nature. Study what he will take or what he will go for . . . that’s why all guys is not drummers that’s drumming.

For a fact, you got to use diplomacy. You must use that. You got to study something that will make them work. You can’t holler at a man, you can’t dog him. Not in music. It’s up to me to keep all that lively. That’s my job . . . There’s more beside drumming than just beating. It’s my job to know what that part is—I got to find it. When I sit down in a band, that I hunts for . . . I find the kick to send ’em off with.

. . . You see a band dead: a drummer can liven up everybody, make everybody have a different spirit. And he can make everybody pretty angry, too. And he can have ’em so that they be so angry with him, but they have to play.

“We’ve grown a lot since then,” Haynes said, speaking for all drummers. “Baby Dodds said he would want to know what tunes his band was going to play, and the guys in the band would say, ‘What do you care? You’re only the drummer.’ Shit. Makes a difference, man.”

It has become almost a cliché to compare Haynes’s improvising to the sound of the timbales player in a Latin band, but he has never talked very specifically about Latin music. He told me that he used to be friends with Ubaldo Nieto, the timbalero from Machito’s orchestra. I suggested that we listen together to Machito’s “Tanga,” recorded at Birdland in 1951.

This “Tanga” changes its atmosphere several times, through switches of key or tension building from different sections of the bandstand. Then suddenly the entire governing language alters. Cuban rhythm becomes swing; you hear a drum kit and cymbals instead of conga and timbales, and Zoot Sims starts playing a jazz tenor saxophone solo. Haynes confirmed that it was Nieto, changing over to a drum kit midsong.

“We were always playing opposite Machito in Birdland in those years,” he said. “And I always did like the sound of timbales, the approach. Sometimes when I’d play my solos, I’d approach the traps with that same effect, like when I hit rim shots,” catching the head and the rim of the drum at the same time. “A lot of the older gentlemen, like Chick Webb and Papa Jo, they did rim shots too. But doing it with no snares on, with that tom-tom sort of Afro-Cuban feeling, I always liked that. So lots of times my solo would be sort of patterned on that style of playing. On one record I did called We Three, with Phineas Newborn and Paul Chambers, I’m playing the high hat with a sort of beat that Uba would play.” (The recording is from 1958, and the song is “Reflection.”)

Finally we listened to Sarah Vaughan singing “Lover Man,” from 1945, with Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker. (The drummer is Sid Catlett.) It wasn’t what Haynes expected; it is what he called a walking ballad, but not as extravagantly slow as the kind he had in mind, the version he recorded with Vaughan in 1954.

Haynes loved the five years he worked with Vaughan. She had impeccable timing, heard well enough to correct a bass player’s chord changes, and filled in on piano when necessary. She sang virtuosically on stage and hung out virtuosically afterward. Haynes suffered his first hangover after going to an after-hours bar with her. (It was Philadelphia, 1953, and Gordon’s gin.)

“She sang some of the slowest ballads, probably, in the world,” he said. “And in the fifties, we had bass players like Joe Benjamin. Bass players in those days had a way of letting the notes ring out. We don’t get that with a lot of young bass players today. Musicians used to say that Joe Benjamin was like a whole band. He could make a sound last—instead of saying boomp, boomp, boomp, like a thumper, thumping on the bass instead of drawing out the beauty in the instrument—he would play BOOOOM, BOOOOM, BOOOOM.

“With drumming, there was an art to playing it and making it sustained, making it sound full with brushes. But you’ve got to have the right rhythm section to make it sound effective. And we did, every night. Moment by moment, there was always something musical happening,” he said.

“To have played with all the people we’re talking about? Jesus Christ. When I go through it, I’m reliving everything I’m talking about. It feels like a dream, going back.”

He had talked about Billie Holiday and Sarah Vaughan. What about Ella Fitzgerald?

“I played with Ella Fitzgerald for the whole summer of 1952,” he said. “That was hard. It wasn’t like playing with Sarah. Hank Jones was the pianist, and Nelson Boyd was the bassist. It was like playing with a big band; she had a lot of energy, and she could swing. One night we played in Rhode Island, a club. That weekend, opening up, they had one of those organ trios. Now, this organ trio was on fire. And after that, Ella said to us, ‘Y’all are not swinging.’ Can you imagine me and Hank Jones on the bandstand not swinging?

“But it’s understandable. She was feeling the threat of having that organ trio opposite her. She was a beautiful person; she’d give you good money. I remember one night we played outside of Baltimore, Sparrows Beach—that’s where all the black people could go, because they couldn’t go to a lot of other beaches in D.C. or Baltimore. We did a gig there on Sunday afternoon. Her driver’s nickname was Mississippi. He drove us from New York, in her Cadillac, to Baltimore. Coming back, we had a gig that night in Harlem, at a place called the Renaissance. Traffic was backed up all the way from Maryland to New York. When we got to New York, it was twelve midnight. She sat in the car and cried; she said it was the first time she ever missed a gig. And gave us some money anyhow.”

It is the time he spent with Vaughan—1953 to 1958—that he rates highest. “The audiences were dressed,” he remembered. “People were respecting the music. Not that they didn’t respect it when I played with Bird, but sometimes you didn’t know whether he was going to show up, or whatever. The musicianship during those years, the places we played—it was enjoyable. Plus I got a check every week. And during that period, man, her voice was . . . mmm. That shit was uncanny.

“And that was the first time I ever went to Europe. In Paris, we played with Coleman Hawkins and Illinois Jacquet on the same show. I backed up Coleman. And that was the first time I ever had my picture on the cover of a magazine. In Paris.”

Set List

Count Basie, “Swing, Brother, Swing,” from America’s #1 Band!: The Columbia Years (Sony Legacy), recorded 1937.

Count Basie, “Queer Street,” from America’s #1 Band!, recorded 1946.

Coleman Hawkins, “Woody’n You,” from Rainbow Mist (Delmark), recorded 1944.

Machito and His Afro-Cubans, “Tanga,” from Carambola (Tumbao), recorded 1951.

Dizzy Gillespie, “Lover Man” (with Sarah Vaughan), from Odyssey: 1945–52 (Savoy Jazz), recorded 1945.