The Mechanists’ Guild was the grandest building Robert had ever seen. Lily paid their hansom fare and they climbed the stone steps that led up to the arched entrance, hidden beneath a three-storey-high classical pediment of finest marble. A single gold cog hung above the entrance – the insignia of the guild.

Robert and Lily pushed open the front door and entered, while Malkin gave one last glare at the cabbie’s horse and slunk in behind them.

At the end of the long foyer, a mechanical man in a porter’s uniform sat behind a big mahogany desk. His squashed-tin-can of a head was bent over a large ruled ledger and he was softly muttering sequences of binary numbers. “O-one-zero, z-zero-one, one-one-zero-one.”

Lily approached the desk, grateful that this time she didn’t have to ask after Selena, or the Doors. “Excuse me, Sir,” she said.

The porter looked up, his irises whirring as they focused in on her.

“We wondered if you could help us? We’re looking for our father, Professor John Hartman.”

“Lily’s father,” Robert added. “He’s working on a project for the Queen’s Jubilee.”

The porter shut his ledger with a snap. “I know the professor. He’s been in and out. Using one of our labs, as a matter of fact, the biggest one…z-z-zero-one. Shall I take you there?”

Lily nodded and gave him a relieved smile.

“What is wrong with your voice?” Robert asked the mechanical man as he led them along a ground-floor corridor.

“I w-was attacked in the s-street by Luddites,” the porter said, “and n-now I have a b-binary stutter.”

“How horrible!” Robert exclaimed.

“We’re so glad you’re all right,” Lily added. “But what are Luddites?” she whispered to Malkin.

“People who are against new technology – who want to destroy mechanicals.” Malkin shivered to the tips of his ears. “To wipe us from existence.”

“Why would anyone want to do that?”

“Because they think we take their jobs. But mostly because we’re different,” Malkin replied.

“And t-to make us scared,” the porter added.

“Oh.” Lily put a hand to her heart. She knew what being different felt like.

“H-here we are then! One-zero!” the porter exclaimed, stopping at a door at the end of a long passageway.

The room did indeed have a number ten painted on its double doors. The porter opened them and ushered Robert and Lily inside.

They stepped into a hall that was almost the size of an airship hangar. A tall sliding screen door at the far end was rolled aside to reveal a courtyard beyond. Floor-to-ceiling shelves ran down one side of the room, filled with arms, legs and torsos – spare parts for mechanicals.

But the most amazing thing about the hangar-sized space wasn’t any of this. Instead it was the creature that stood at the room’s centre: the Elephanta – the world’s largest mechanical elephant.

Lily had only seen a real elephant once before, when, as a young girl, her mama and papa had taken her to the Zoological Gardens in Regent’s Park to show her the two Indian and the one African elephant kept there. The Elephanta was larger than any of those. Her legs looked to be the height of two men, and the round body, towering way above them, was as big as a small house. Lily reckoned her to be about three times the size of her real-life counterparts.

The Elephanta’s skin was sculpted from wood and covered in hand-etched scars and wrinkles. Her ears were made of big flat leather hides, bound together with rivets, and her eyes were made of blue crystals. Rusty iron tusks sat either side of her trunk, which was made up of hundreds of wedge-shaped segments of wood that fitted together in a snaking shape. A ladder leaned against the far side of the Elephanta, and a panel in her flank had been flipped open, rather like the hood of a steam-wagon.

An iron figure with bow legs and wearing a leather belt of tools was standing on the top step of the ladder, leaning forwards and fiddling around deep inside the cogged stomach of the Elephanta. The figure was simultaneously humming and hammering loudly.

The porter’s jaw creaked as he opened his mouth wide and called up, “Captain Springer, there’s some human children belonging to z-z-zero-John to see you!”

The figure straightened and there was a clang of metal against metal as it banged its head on the Elephanta’s hood. Then there was a prink-pronk-clank! that sounded like something being dropped and tumbling down into the workings, and then a jittery shout. “Curse these jangling interruptions! And curse this clunking thing! Why won’t it work?”

“Oh zero-dear!” the porter muttered. “Have we caught you at a bad time?”

“No, no, Mr Porter!” came the echo from above. “It’s a perfectly acceptable hour, according to my clockwork!” Captain Springer emerged from inside the Elephanta’s interior and as he climbed down the ladder towards them his face broke into a bolt-filled grin.

“Well, grind my gaskets!” he cried. “If it isn’t the tiddlers and Malkin! By all that ticks,” he continued, “what the devilled kidneys are you doing in London?”

He stepped from the ladder and gave Lily and Robert a big creaky hug, ruffled Malkin’s fur and gave Mr Porter a friendly slap on the back, which produced a loud bang like a bell.

“We came to find Papa,” Lily explained, when Captain Springer had quite finished greeting everyone.

“I’m in trouble,” Robert added, “and we need his help.”

Captain Springer tapped a hand absent-mindedly against the Elephanta’s stilled leg. “Your father went back to Brackenbridge this morning,” he explained. “He sent a telegram to Mrs Rust to check everything was in order, because he was so worried about the news he had been getting. Then, when he sent a second telegram and didn’t receive a reply, he thought it best if he went back home – straight away tickety-tock! – to find out what had been going on. But it sounds as if he’s gone off on a bit of a wild moose chase!”

“Oh dear,” Lily said, “I feel rather guilty.” She stared up at the grey flank of the Elephanta. “And we’ve interrupted his work for the Queen’s Jubilee parade.”

“Bilge pumps and brake levers!” Captain Springer gave a shuffling shrug. “Don’t you worry about that, young madam. There’s no way on this green earth that we could have this clattering mech-elephant up and running in two days, no matter how much we tinkered with it. Not even for the Queen and her jamboree parade!”

Robert peered up at the massive breastplate of the beast. Its side was open and he could make out an interior filled with cogs the size of cartwheels and ratchets and springs as big as his head. The Elephanta was one of the most impressive mechanical engines he’d ever seen – the workings were almost as grand and complex as those in the Big Ben clock tower. To his inexperienced eye they looked all present and correct – there didn’t seem anything particularly wrong with it.

“How is she damaged exactly?” he asked. “Maybe Lily and I can help?”

Captain Springer shook his head. “Oh no, no, nope! If John can’t fix the blessed thing then – sure as eggs is chickens – you won’t be able to. You see, there’s a part missing.” He beckoned them round the front of the beast and they stared up at its still head. In the centre of the forehead was a massive dimple.

Captain Springer pointed it out. “That space used to house the Blood Moon Diamond… People think the diamond’s ornamental. But it’s what makes the creature run, what makes her clockwork turn, her insides jigger. Same as for every mechanical. No, she won’t take a single step without it. She hasn’t moved a cog since it was stolen fifteen years ago. I don’t know what Professor Hartman was thinking when he took on this repair job. Even with all the time in the world, it would be an impossible task.”

“The same for every mechanical?” Lily said. “What is? What do you mean?”

“Crenellated clockwork! Did John never explain that part?” Captain Springer asked. “Us mechanicals –” and here he gave Lily a nudge with his elbow – “we’ve all got fragments of Blood Diamonds in our hearts. They’ve a special energy that makes our motors turn, keeps our little synaptic-springs snapping!”

Lily put a hand to her chest. Blood Diamond…inside her? Occasionally she felt as if there was something alien in there – perhaps it wasn’t just the Cogheart, but the lump of diamond at its centre?

“The gemstones mined in the Red Caves,” Captain Springer continued, “like the Blood Moon Diamond, they contain life-energy. They’re what you might call living-diamonds, and they power us. But the Blood Moon Diamond was the biggest of them all, found in 1815, on the date of the century’s shortest total lunar eclipse – so they say. It was gifted by Prince Albert to Queen Victoria on her birthday. She wanted to use the stone to power a mechanical, so she had the Elephanta built, and set the jewel in her forehead. It was perhaps the greatest mechanimal of all time – until Jack Door stole the Blood Moon Diamond and it stopped working!” Captain Springer wrung his hands together. “Anyway, enough of all that. You still haven’t told me what you’re doing here?”

“We’re searching for my ma. She’s in grave danger,” Robert said. “But all this stuff about the Blood Moon Diamond – it ties in with that too.”

Captain Springer looked confused. “What d’you mean?”

“He means we’ve had a few run-ins with the Jack of Diamonds himself,” Lily explained, flourishing the card Mrs Rust had found.

“Gridirons and girders!” clucked Captain Springer. “Did you get this from Jack?”

Lily nodded. Admittedly it had sounded a little too casual the way she’d put it.

“We think Jack Door is looking for my ma,” Robert explained. “And for this…” He pulled the locket out from beneath his shirt.

“By my iron britches, that’s a most marvellous thing!” Captain Springer examined the locket. “What is it?”

“A locket,” Malkin said dourly.

“What’s it do?”

“It’s some sort of map,” Lily said. “To what, we don’t know. There’s a code but we can’t translate it. Robert’s ma would know the answer, we believe, but we haven’t been able to find her.”

“Yet…” Malkin added.

“Your father would be the person to ask, when he returns,” Captain Springer advised. “He’s an expert on cryptographs and cyphers.”

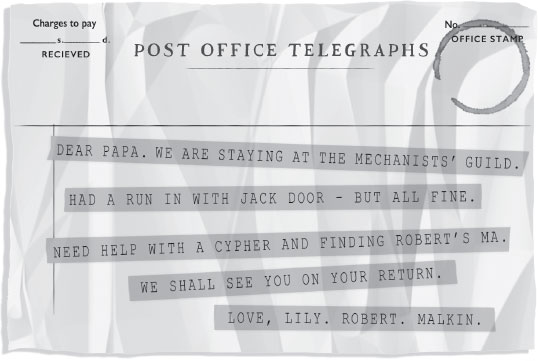

“Then we should get word to him immediately,” Lily replied.

“We have a telegraph office in the guild,” Captain Springer said. “We’ll wheel round there and you can send a wire. Let John know you’re safe and sound. Meanwhile, Mr Porter will find you a room where you can rest tonight.”

“Z-z-zer-oh-dear! Of course, of course!” Mr Porter said. “I shall see to it right away.”

Captain Springer led them to a small musty room with a glass door that stood ajar, on which were etched the words: Mechanists’ Guild Telegraph Office.

He nodded to the woman behind the counter, who sat beside the telegraph machine. “This is our telegraphist – Miss Dash,” he explained to Lily. “She’ll help you send your telegram.”

Miss Dash gave a shaky nod of her head. “Call me Dot, please – Miss Dash is so formal, don’t you think?”

She wore a visor hat bolted onto her forehead, and held a bunch of telegrams in one hand, reading them and then tapping out the letter codes at super-fast speed with the other using the telegraph key in front of her. Wires splayed from the machine out across the ceiling and through a hole in the back wall, and on, Robert imagined, to telegraph stations all around the country.

Lily opened her mouth to speak to Dot, but the telegraphist pointed at a wooden shelf that ran along the far side of the room holding a row of blotters and ink stands and dockets of telegraph forms.

“Fill out a telegraph form, please,” Dot said.

Lily did as she was told. Picking up a pencil, she stared at the docket.

So much had happened in the last two days, she didn’t know how to fit it into such a brief message; plus she was mindful of the fact she didn’t want to upset Papa with stories of danger and derring-do – best to keep her sentences short and calm in tone.

When she’d finished, she tore the page from the pad and headed back to the counter.

Dot had disappeared somewhere in the office out back, but Lily rang the bell on the desk and handed her the message when she reappeared.

“Dot, this wire is for Professor Hartman at Brackenbridge Manor,” Lily told her. “It is to be delivered directly to his hand; no one else must receive it in his stead.”

“Certainly, Miss,” Dot said. Lily watched as she tapped the coded words into the machine by her side, her fingers a blur. When she’d finished, she looked up and smiled at Lily. “Your father should get the telegram later this evening. I imagine he’s only just arrived home, so even if he makes his way straight back, he probably won’t return until tomorrow.”

“Zero-oh-dear-oh-dear, there you are!” Mr Porter had reappeared. “The guild’s accommodation is rather full, I’m afraid. All the professors and the mechanists are arriving for the Queen’s Jubilee. But I’ve given you both your father’s room until he gets back. There’s a camp bed for one of you to use. I suggest whoever’s joints are the least rusted.”

“Thank you,” Lily said. “I’m sure we’ll be most comfortable.”

The room itself was in a separate wing at the end of a long corridor filled with odd glass cases, each containing strange inventions.

“These are some of the earliest mechanicals,” Mr Porter explained, pointing them out as they passed. He indicated a scruffy-looking duck in a case: “That’s Vaucanson’s famous pooping-duck.”

Waving at another case: “This is James Cox’s singing peacock clock.” And nodding at a third: “That’s Whisty, the first card-playing mechanical. He was a bit of a gambler, but he had a good poker face, as you can see, because he couldn’t change his expression.”

Robert noticed that Whisty, though run-down, had laid the Jack of Diamonds on the green baize table in front of him. It made him think of Jack Door, and he shuddered at the thought that the criminal was still looking for him and his ma.

Suddenly he felt rather downhearted. They couldn’t just wait around for Lily’s papa to return – that would be a whole extra day. They needed to find his ma as soon as possible, before Jack got to her.

They had arrived at their room. Mr Porter showed them in. A long tapestry of cogs filled one wall, a big four-poster bed another, and beneath the large picture window, a camp bed had been set up. The furniture was practical and sparse and dotted with Papa’s things, and the floor was filled with his cases and trunks.

As they made themselves at home, Lily realized they hadn’t eaten since the meat pie at breakfast, so she asked Mr Porter to bring them some jam sandwiches and a glass of milk each before they went to bed.

“We should go tomorrow and ask Anna for help,” Robert said, after Mr Porter had left. “In the meantime, I’m going to try my best to decode the message on the back of Selena’s locket.”

“Good idea,” Lily said. “And I shall look through her book.”

When the tray of food arrived, they sat on the floor amongst Lily’s papa’s trunks and ate with gusto. The night was muggy and humid; with the city’s closeness, the air felt completely different to the freshness of summer in the countryside. As they ate, Malkin crawled down the end of the four-poster bed, settled himself on a cushion and promptly fell asleep, his cogs fizzing slower and slower as they wound down.

When Robert and Lily had finished their milk and sandwiches, Robert took the Moonlocket from around his neck and stared at the back of it. He was still trying to work out what the map and the message meant.

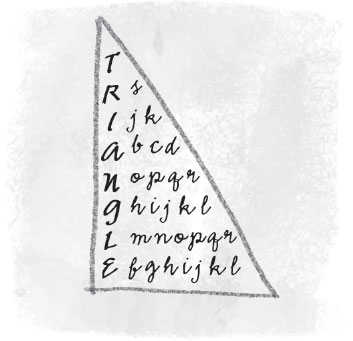

Lily had been flicking through Selena’s book, The Boy’s Own Book of Games and Tricks, when she noticed a chapter on cyphers. There was one called the Triangle Cypher. Suddenly she remembered the triangle at the end of the two-word code on the locket. This book had belonged to the Doors once…could that be it then?

She pointed at the page of the book. “Robert, I think I might have worked out how to solve the Moonlocket code!”

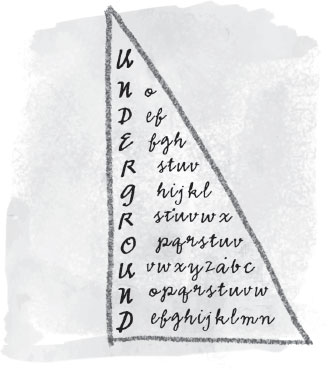

Robert leaned closer, peering at the page as Lily read the instructions. “You draw a right-angled triangle and place your word down the straight side, see? Then add letters to fill the space of the triangle after it; with each line you add one more letter.” She wrote a word down the page to demonstrate:

“When you’ve finished, you read the code off the angled side, so triangle becomes tskdrlrl – understand?”

Robert nodded. “And if we reverse that method with the locket code words,” he said, “we’ll get their translation.”

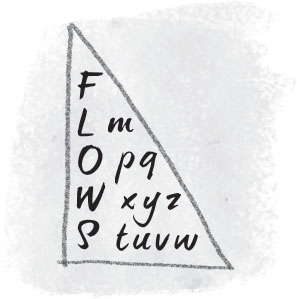

So Robert took the locket off and they looked at the two words:

fmqzw uofhvlxvcwn

They took one word each and set to work on separate sheets of paper decoding them. When they’d finished they put the two sheets together, and this is what they had:

Robert’s word was: flows.

And Lily’s was: underground.

“Flows underground,” said Robert. “What does that even mean?”

“It must mean something.” Lily gave a big yawn. “But I’m too tired to try and work it out this evening. It’s getting late, we should probably call it a night.”

Lily found two fresh nightshirts in Papa’s trunk; one she handed to Robert and one she kept for herself.

“Why don’t I take the camp bed?” Robert said.

“You’re sure?” Lily asked.

He nodded. “Of course.”

Shyly, they turned turned away from each other and began to change. Lily hunched her shoulders as she put on her nightshirt. She was self-conscious of the vivid white scars on her chest and back – the lasting evidence of the steam-wagon crash from that winter’s night seven years ago that had killed Mama. Some of the scars had healed since then, until they were barely visible, but others – like the cuts on her chest from the Cogheart transplant Papa had done to save her – were still evident. Tonight those scars throbbed painfully at the sudden memory of her loss. She felt for Mama’s ammonite in the pocket of her folded pinafore, and held the gift tight against her chest.

Robert was distracted too. He put the Moonlocket back round his neck. He didn’t even like to take it off to sleep any more – he was so scared that someone might sneak in and steal it from him.

When he turned to face Lily, she was in her nightshirt and climbing into bed. Malkin was curled up on the pillow beside her. Lily pressed a button on the wall above the big four-poster bed, and they heard a clicking of clockwork in the walls as the curtains drew themselves around her.

“Goodnight!” she called out to Robert.

“Night!” he whispered back.