Chapter 1

Bear Shamans and Plant Healers

The souls! They are not in the bodies. The bodies are in the souls!

Christian Siry, Die Muschel und die Feder

We have almost forgotten: animals are our helpers and companions. All too often we see them only in a utilitarian way. Cats are useful because they hunt mice, dogs protect property, cows produce milk, and horses are here for us to ride. But when we see animals with the eyes of the heart, we realize that their value cannot be expressed in merely economic and utilitarian terms. While studies have shown that children who grow up with pets are psychologically more well-balanced and that old people also fare better, especially if they are alone, with even just a goldfish or a bird, psychological well-being is not the aspect I want to emphasize. My area of interest goes into a much wider perspective, into the archetype of the animals, and, in this particular case, the mythological bear archetype.

Animals have very subtle senses and often sense what is approaching the people, or even other animals, they live with long before the people themselves become aware of something. It seems they can see into energetic, astral dimensions that are invisible to us. I believe that they even sometimes deflect the karmic suffering, or a similar serious illness meant for their owner, by taking it on themselves, even to the point of dying from it. Animal allies can help us understand and comply with our own fates better by communicating to us telepathically. Pets can do this, but wild animals are even more powerful because they haven’t been through the process of domestication. Some of us have close contact with wild animals and may have the opportunity to experience the phenomenon with deer, wild rabbits, coyotes, birds, snakes, and even tiny animals such as ants and bugs. For people who go far enough into the wilderness, contact with mountain lions, big game, and bears is possible.

In our schools, we do not learn about this connection to animal souls. Our attention is focused on other “more important” things, on lifeless mechanisms and abstract data, which makes it possible for us to function in “the system.” But the soul needs something else in order to be happy. Some of us are lucky enough to learn in childhood from relatives or friends how to connect with animals. But even beginner adults can connect with animals simply by opening their souls more when out in nature. Animal spirits tend to appear when we are open to them. Maybe a certain kind of animal has always interested you, or someone in your family knows about an animal that your ancestors were connected to or has always had a special friendship with your family.

Understanding the Nature of Animals

Animals are very much closer to our souls than inanimate and completely mute plants or rocks are. They are embodied souls, just like we are. Just like us, they live within a wide realm of likes and dislikes, pain and pleasure. I believe that plants and minerals also actually possess something like a sentient soul and a wise spirit—but these are not directly connected to their physical bodies, as is the case with animated, breathing human beings and animals. Plant and mineral “souls” and “spirits” are definitely much more distant; they exist far beyond their physical bodies, effused in macrocosmic nature. For this reason, logic and material rationality cannot help us behold “soul” and “spirit”—and that is why science, which focuses only on what is logical and can be measured and weighed, cannot show us this aspect of our existence. But shamans have the ability to step outside of ordinary daily consciousness. A strong shaman, who may even have a bear as a totem, can also communicate with these even more remote kinds of spirits.

Animals are living beings. Every animal breathes. Its soul flows along with the rhythm of each breath. Feelings, moods, and emotions are closely connected to the rhythm of breathing in and out. The old English word deor, related to our word “deer,” comes from Indo-Germanic dheusóm (Old English deor, Dutch dier, Swedish djor) and means “breathing, animated being.” The English word animal, which is from Latin animal, animalis, is related to the concept anima, animus (soul, breath, wind, spirit, living being). When an animal or a human being stops breathing, the anima, or soul, leaves the body and goes back to another dimension; the warmth of life disperses, and the body stiffens and begins to dissolve into its material components.

As any shaman or anyone who knows animals will tell us, animal souls are pure and cannot be false like human souls can be. No abstract thoughts, no “creative intellect,” no “cultural constructs of reality,” and no lies split animals from their direct natural environment. Animals are directly and undividedly involved in their environment and surroundings. Smells, sounds, and moods of the environment; sun and moon rhythms; and the seasons determine their activities. They are very much unlike humans who have complicated and abstract symbol systems, who communicate with words, and whose thoughts are linked to a complex and huge physical brain. Nature itself “thinks” for animals. They partake in the orderly intelligence of the macrocosmic spirit.

Seen in this light, it is not really all that clear that the cerebral-cognitive abilities of animals are less developed or less evolved than those of humans. An animal’s spirit is not an individually incarnated one; rather, it is part of a “group spirit”—as most indigenous peoples describe it—or part of the spirit of the “lord of the animals” or “in the otherworld,” with the “mother of the animals” in a cave, inside a mountain, or “on green pastures in the otherworld.” As anthropologists hear from native peoples, this “group spirit” is a spiritual being, a deity, a deva. It is that which guides the wild geese to the sunny south in late fall, guides the birds as to how to build their nests, warns the animals about tidal waves or earthquakes, and lets them know which plants are edible, which are healing, and which are poisonous. In modern times, this is called “instinct,” a word that was introduced into science in the seventeenth century and simply means “drive” (from Latin instinguere = to prod on, to drive on as a shepherd drives sheep with a stick). But what is it that drives the behavior of the animals? Today, we believe we know: “genetic programming” guides hereditary, stereotypical behavior that has not been learned and can barely be changed by learning processes. Exogenous forces (warmth, light, smells, etc.) trigger endogenous, genetically fixed reactions—this is the present materialistic-positivistic doctrine based on analyses and measurements in laboratories.

Native peoples are not known to have laboratories occupied by busy scientists wearing white jackets, nor have they developed an exclusively rationalistic method to achieve knowledge. Their knowledge of animals is based on living near the wild feathered or furry animals of their surroundings. These human-animal communities stretch over many generations. Humans and animals know each other. They have always had relations with each other—positive and negative—and live in a symbiosis. Native peoples know every sound in their wild natural surroundings. They can also read the finest traces of other beings exactly, such as when leaves have been nibbled on, fresh tracks have been made on moist ground, fur has been snagged by bushes, or feathers are found in unusual places. They have observed animals closely and intensively and over many generations.

But they not only observe externally; they also go beyond the ordinary senses. Dreams and visions as well as shamanic techniques such as deep meditation, long fasts and vigils, trances, dances and drumming for some tribes, and mind-altering plants for some others connect them to the specific animal spirit, with the lord, or the mother, of the animals. They dress in the fur of the animal of a bison, an elk, or a bear, move and dance the way the animal moves, and sing age-old songs about that animal until they are in unison with it and the border between human and animal disappears. Their soul flies then as a raven, owl, or eagle, swims like a dolphin, lopes as a wolf with the pack through the tundra or prairie, or moves as an elk through the forests. Unlike scientists, who only observe animals externally and measure their external reactions, they experience the animals, so to say, from the inside.1

According to Cheyenne medicine man Bill Tallbull, humans are not even necessarily the initiators in this intensive interaction. He explained to me that the animals themselves usually seek contact with certain people rather than the other way around. The animals want to give humans inspiration, dreams, helpful instructions, or warnings. Shamans do not look for their totemic animals. Instead, the animals reach out to the humans that they are willing to protect. Anthroposophist Karl Koenig (2013, 90) writes in a similar vein:

Animals intervene in human lives and humans intervene radically into animals’ existence. They interpenetrate each other’s lives, and it is not only fear and superstition that determine the different taboos, festivities and magical rites. The inner world of the animals, their actions, their behavior, their imaginations and extrasensory experiences have, in fact, a definite impact on the imagination, feelings, and actions of the native people who live in the same environment.

Animals’ telepathic communication with people can be experienced sometimes even from pets or other domesticated animals: One night a cow on the pasture near my house fell into a big, abandoned cement pit full of water that had not been fenced off, and it could not get back out. In the form of the Egyptian cow god Hathor, the cow appeared to me in a dream telling of her distress and where to find her. Authorities arrived just in time to heave her out and save her life. If we are open for it, the connection is there. I also remember how the ants taught me to write when I was a young, slow pupil. I had observed them for hours on end and wrote about what I saw. It was the first time I was really able to write a story. And, once a cormorant’s wing was frozen to the ice in a canal behind our house in northern Freesia because a drastic temperature drop had frozen the ice so suddenly. I felt drawn to go out even into the extremely bitter cold, found the bird, and was able to get its wing free. I felt like the bird had literally called me out to gain my attention and help.

For people who still live as hunters and gatherers or as simple tillers, the lord of the animals—the archetypal animal spirit or the primordial animal deity—is not some abstract idea or merely a matter of belief. It is a direct experience. Shamans do not imagine they can talk to animals; they do talk to them. The shaman gets answers and acts accordingly, and this communication has concrete effects in the “real” world. What he or she finds out from the animals is not a product of subjective fantasy. Likewise, a young Native American man talks to the animal teacher that appears to him in a vision quest and learns from it what duties he is to fulfill in this life. Siberian shamans speak with the lord of the animals who tells them the location of the wild animals gifted to the humans to hunt and satisfy their hunger. The Inuit Angakkok seeks out Sedna, the mother of the sea mammals, to find out where the seals are and ask permission to hunt some of them. Animal spirits also show healers which healing plants to use. Animal spirits who have befriended people warn them of approaching danger.2 Animals also impose rules of conduct and taboos on people that must be adhered to. The gods will also often temporarily take on an animal form.

Our own human ancestors were generally much more connected to nature before industrial times demanded their constant attention, and they also had access to the magical side of animals. Fairy tales, myths, and supposed superstition, all of which have a very long pagan history, demonstrate it definitively. Helpful animals that speak appear again and again to the heroes in these tales, next to fairies, dwarves, and numerous otherworldly beings (Meyer 1988, 114). According to the original Grimms’ Cinderella tale, doves and birds help Cinderella with the nearly impossible task of separating the bad peas from the good ones in time to go to the ball, and two doves in a hazelnut bush (growing over Cinderella’s mother’s grave) tell the young prince which of the young women are the false brides—as he rides on his horse with his presumed bride, the doves coo, “Blood in the shoe, blood in the shoe, the wrong bride are you!” (In the original version, the first stepsister cut her toe off to fit into the shoe and the other cut her heel off, thus fooling the prince until the birds told him as they were on their way to his castle). In another Grimms’ tale, The Goose Girl, Falada the talking horse tells the princess what the imposter, formerly her servant, is hiding from her. Ants also help the dumbest and youngest of three brothers find hidden pearls, ducks help him find a key that was sunk in a lake, and bees show him who the true princess is by landing on her lips because she is the sweetest. They help him, whose brothers are always shaking their heads over his stupidity, because he is good and kind to the animals. Fairy tales are full of such examples. Even Christian tales are full of stories about animals that have befriended people. A dog and a raven bring Saint Roch bread every day so that he will not starve as he struggles with pestilence. Bears bring wood for Saint Gall so he can build chapels.

We modern, educated people may smile condescendingly and comment, “Yes, but those are just fairy tales.” Yes, those are fairy tales, in the literal sense of the word “tales.” The German word maer (Old High German mari, from which comes the German word Maerchen = fairy tale) means “lore, narration from an otherworldly dimension.” Everyone knows that fairy tales are not based on empirical, scientific facts, but they are still true—an older name in English is actually “wonder tales.” They allude to the more essential, transcendent nature of reality. The pure spirit of the different animals, which is filled with wisdom, can only be grasped with shamanic abilities. True tales and legends can tell us about these things.

Animal Allies

Indigenous peoples tell us that each person has his or her animal or animal helpers that are connected to the person for better or for worse. The Aztecs called a person’s doppelganger nagual, that is, the animal that mirrors the person’s wild nature. The nagual often shows itself during pregnancy. During the night of a birth, Central American Indios watch to see and hear which animals appear. If a jaguar, a boar, or another strong animal appears, then the newborn will surely have a strong personality and will possibly become a shaman. Often the child will be named after his or her animal doppelganger. For European peoples of ancient times, such thoughts were not at all strange either. In Scandinavia, animal doppelgangers were called “accompanying souls,” or fylgia (related to “follow”). The souls of strong men or women roam the woods as bears, wild pigs, stags, or wolves. They fly through the skies as eagles, ravens, and swans, and as salmon or otters they swim through the waters (Meyer 1988, 262). The warrior Bjarki (described in a story in Chapter 13) fought as a bear on the battlefield while his body lay rigidly in a deep trance.

The connection to powerful animals is shown in such names as Rudolf (Old High German hrod and wolf = glorious wolf), Bernhard (Old High German bero and harti = powerful, persevering bear), Bjoern (Swedish for “bear”), Bertram (Old High German behrat and hraban = shining raven), Arnold (Old High German arn and walt = he who rules like an eagle), Falko (Old High German falkho = hawk, falcon), Art and Arthur (Old Celtic arto = bear), and Urs or Ursula (Latin ursus = bear). Such names are echoes of totemic name-giving in the realm of European culture.

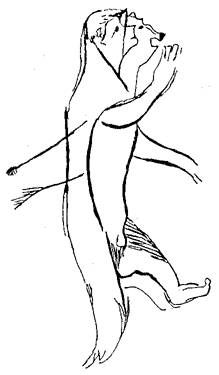

A shaman on a magical journey, riding a bear. The drawing on the shaman’s costume is that of a Samojedic shaman from Siberia.

A shaman without an animal familiar would be weak and helpless, while any animal can be this kind of friend. Ravens can fly out for the shaman and find things that remain otherwise hidden, as was the case for the Old Nordic god, Odin. While his body is lying rigid and in a trance, a South American shaman can send his spirit out in the shape of a jaguar to roam the jungle. With the help of a wild boar spirit helper, a jhankrie, a Nepalese shaman, can sleuth out the disease or the magic arrow that is in the patient’s body making him sick. Native American shamans, or dream dancers, fly in the form of an eagle while doing the sun dance and return with messages from high spirits to help guide the tribe. “Changed into werewolves,” Lithuanian peasants used to comb through forests and wilderness in the full moon night of May, fighting the winter spirits that bring the last harmful frosts of the year.

Legends are also full of prophetic swans, talking horses, magical stags, and other animals that interact with shamanistic personalities. Albeit our long-forgotten heritage, shamanism is also even relevant for modern people. Shamans, who were once rivals to Christian missionaries, were discredited and bedeviled in the course of Christian conversion in Europe. But, for a long time, many not-quite-converted people remained and would send their animal familiars, spiritus familiaris, to roam the forests at night as wolves or bears, moving stealthily as black cats through the villages, or flying as wide-eyed owls.

Although brutally abolished during the Inquisition of the late Middle Ages, witchcraft is one of the last vestiges of old European pagan shamanism (Mueller-Ebeling, Raetsch, and Storl 2003, 48). However, animal alliances did not die with the ascendance of Christianity; Christian traditions, too, include animal companions. Examples include the donkey at the crib, Joseph’s riding animal, cows, and sheep at the holy infant’s manger, Luke as a steer, John as an eagle, and the Holy Spirit as a dove. Konrad von Wuerzburg even saw Christ as a weasel: “Christ the high weasel in all of his power, slipped down into the depths of hell and bit the murderously poisonous worm to death” (Zerling and Bauer 2003, 333).

The tradition of shamanism and its acquaintance with protective animal spirits is still very much alive for native peoples around the world. For Native Americans, every medicine man or woman has an animal helper that gives them strength, sends dreams, and accompanies them on trips into the spirit world. The animal spirit can adopt the medicine man or woman as a child or even marry him or her—even if the person concerned already has a human spouse. “Eagle dreamers,” “bison dreamers,” and other medicine people who are bonded with the coyote, the ants, or the badger usually show characteristics of their animal familiars in their own personalities. A shaman who has a stag familiar, the “stag dreamer,” will be robust, very healthy, and, like a stag with his harem, enjoy many women. He will be able to heal sick women and possess love magic to bring young men and women together (Lame Deer and Erdoes 1972, 155). A buffalo shaman is a great visionary who can lead his tribe safely, like a buffalo bull would. A snake shaman, who is usually summoned to this role by the bite of a poisonous snake, is connected to these reptiles and knows the herbs and songs that can cure snake bites. The soul of the wolf shaman is pure like freshly fallen snow and can roam far into the spirit world. A rabbit medicine man is very clever, but, like a rabbit, he can also die of shock (Garrett 2003, 29).

Of all the medicine people, the bear shaman, or bear dreamer, has a very special status because bears are, in fact, almost like humans. The Quechua people in the Andes call bears ukuku, which means half-human. Those who know bears well tell us that each bear has a very individual personality. However, unlike humans, its ego is not capsuled off and caught up in a net of culturally specified verbal and symbolic constructs. Despite the bear’s particular individuality, it remains intimately connected to the macrocosmic group soul, to the bear spirit, to nature. In this way, the bear is a mediator between the worlds, and this is exactly how many indigenous people have experienced the bear. For them, a bear is not simply an animal; a god-like being is hidden under his bearskin. For many Native American and Siberian peoples, such as the Khanty, Tungus, Samoyed, and Finns, the bear is a go-between for the heavenly god and the earth goddess. The bear, this animal of Earth and caves, is attributed to the earth goddess and the fertile female realm. But at the same time, it is also attributed to heavenly spheres, highest gods, and fertile weather deities. Like a genuine shaman, it is a being of both worlds. A bear is a forest animal and a forest human, a strong guardian of the threshold to the otherworld. The bear is the messenger of the gods and as such, a benevolent guest of the middle world, the human world.

An Old Stone Age engraving from La Marche, Vienne, France

A bear shaman partakes of the bear’s being. He wears a bear mask, bearskin or a necklace, or amulet of bear teeth or claws, all showing that the bear spirit is his totem; he also possesses the ferocious power of a bear, which can cause even the worst demons of sickness to flee in fear. It follows that a shaman who has been called by the bear spirit is one of the strongest healers. For the Kirati, a tribe in eastern Nepal, which still follows an old shamanistic nature tradition, the bear (balu) is considered the grandfather of the shamans. Their shamans always have bear claws with them that function as a talisman, a guru, and a protection (Mueller-Ebeling, Raetsch, and Shahi 2002, 177). They also prefer bearskin for their drums. Anthropologist Christian Raetsch tells that bear parts are taken neither from living bears nor from hunted bears—in order for them to be truly powerful, the shaman has to find them in a trance (Mueller-Ebeling, Raetsch, and Shahi 2002, 251). Even the bark from a tree where a bear has scratched can give power. Mongolian-speaking Burjatians, who live east of Lake Baikal, dry and crumble such bark and mix it with their smudging plants in order to give them more power.3

Tungusic shaman with bear paws (Witsen 1692)

The Plant Healers’ Teacher

According to northern Native Americans and many Paleo-Siberian peoples, bears not only know plants but can also pass this knowledge on to human beings. In addition to observing these animals when they dig up the roots and try out the herbs and barks, the shaman can receive dreams from the bear spirit that inspire healing. Consequently, one who has a direct vision or dream about a bear has been summoned to be a plant healer, or plant shaman. Ojibwa medicine man, Siyaka, explained it to anthropologist Frances Densmore:

The bear is quick-tempered and is fierce in many ways, and yet he pays attention to herbs which no other animal notices at all. The bear digs these for his own use. The bear is the only animal, which eats roots from the earth and is also especially fond of acorns, juneberries, and cherries. These three are frequently compounded with other herbs in making medicine, and if a person is fond of cherries we say he is like a bear. We consider the bear as chief of all animals in regard to herb medicine, and therefore it is understood that if a man dreams of a bear he will become an expert in the use of herbs for curing illness. The bear is regarded as an animal well acquainted with herbs because no other animal has such good claws for digging roots. (Densmore 1928, 324)

The famous Sioux medicine man Lame Deer tells that the Wícása Wakan, the shamans, get their power (“medicine”) through a dream or vision sent by an animal teacher.

Much power comes from the animals, and most medicine men have their special animal which they saw in their first vision. One never kills or harms this animal. Medicine people can be buffalo, eagle, elk, or bear dreamers. Of all the four-legged and winged creatures a medicine man could receive a vision from the bear is the foremost. The bear is the wisest of animals as far as medicines are concerned. If a man dreams of this animal, he could become a great healer. The bear is the only animal that one can see in a dream acting like a medicine man, giving herbs to people. It digs up certain healing roots with its claws. Often in a vision it will show a man which medicines to use. (Lame Deer and Erdoes 1972, 152)

Old medicine men of the Sioux used to have bear claws in their medicine pouches. They pressed the claw into the flesh of the sick person so that healing bear power could flow into the patient’s body. The songs of the Sioux bear dreamers ended with mato hemakiye—“A bear told me this.” Then, everyone knew that this medicine man had received his healing power from a bear. The bear dreamers were especially gifted in straightening out and healing broken bones. “These bear medicine people could heal! We had people who were ninety and one hundred years old and still had all of their teeth!” (Lame Deer and Erdoes 1972, 153).

A bear shaman (Catlin 1844–1845)

Sioux medicine man, Two Shields, tells, “The bear is the only animal which is dreamt of as offering to give herbs for the healing of man. The bear is not afraid of either animals or men and it is considered ill-tempered, and yet it is the only animal which has shown us this kindness; therefore, the medicines received from the bear are supposed to be especially effective” (Densmore 1928, 324). A depth psychologist would say someone who can connect with the “bear” in his or her soul, with his or her deeply buried instinct, and also has clear and sharp senses like a bear, will have easy access to comprehending healing plants.

To what degree bears are honored as healers and knowers of wild plants can be seen in the following tale from Algonquians of the eastern forests.

Tale of the Medicine Bear

One day an old man appeared in the village. He came empty-handed and was hungry and sick. His skin was full of abscesses, and he gave off a terrible smell. At the first wigwam, he called out, “Help me! I need a place to stay and some food.”

He was sent away because the family was afraid he had something contagious and the children could get it. He fared no better at the second wigwam and was sent away again. This was repeated again and again throughout the whole village. Finally, at the very last wigwam, he was taken in. A very poor woman who had only a few relatives and lived alone in a tiny wigwam at the edge of the village took pity on him. She invited him in and gave him something to eat and a place to sleep. Because he was even sicker the next morning than the day before, she tried to cure him with her familiar house remedies; however, it was no use and he got even sicker. After a few days, he told the woman that the Great Spirit had visited him in a dream and shown him which plant would heal him. The old man described the plant in exact detail, and the woman went out in search of it in the forest and found it. After the woman used this plant as the patient had been told to use it in his dream, he got well again, and, after a few days, as he was preparing to say goodbye, he suddenly got an attack of fever and fell sick again. Again, the house remedies of the poor woman could not cure him. He was already on the brink of death when he dreamed of another healing plant. Again, the woman found the plant and he became well afterward. As he was preparing to say goodbye once more, he began to shake and suddenly had to vomit. Again, he was sick and again he dreamed of the right healing plant. This went on for one year. Then, finally, he really was healed. He got up from his sleeping place and turned around one more time before going to the door and said, “The Great Spirit had told me that there was someone in this village who should learn how to heal the sick with plants. I was sent to you to teach you and this I have done.”

He stepped out into the sunlight and the dumbfounded woman stared as he left. Just as the old man was disappearing into the forest, he turned into a big bear. It had been the bear spirit who had summoned the woman to become a plant healer.

Black Foot bear shaman during a healing ceremony (Catlin 1844-1845)

A bear shaman or bear dreamer is not only a master of healing herbs but also someone—as seen among the Germanics, Romans, and Celts—who can inspire warriors and bestow them with courage, strength, and discretion in battle. The following is a story about a Pawnee who was a bear shaman and a war chief (Spence 1994, 308).

There was once a boy of the Pawnee tribe who imitated the ways of a bear; and, indeed, he much resembled that animal. When he played with the other boys of his village he would pretend to be a bear, and even when he grew up he would often tell his companions laughingly that he could turn himself into a bear whenever he liked.

His resemblance to the animal came about in the following manner. Before the boy was born his father had gone on the warpath, and at some distance from his home had come upon a tiny bear-cub. The little creature looked at him so wistfully and was so small and helpless that he could not pass by without taking notice of it. So he stooped and picked it up in his arms, tied some Indian tobacco around its neck, and said: “I know that the Great Spirit, Tiráwa, will care for you, but I cannot go on my way without putting these things around your neck to show that I feel kindly toward you. I hope that the animals will take care of my son when he is born, and help him to grow up to be a great and wise man.” With that he went on his way.

On his return he told his wife of his encounter with the little bear. He told her how he had taken it in his arms and looked at it and talked to it. Now there is an Indian superstition that a woman, before a child is born, must not look fixedly at or think much about any animal, or the infant will resemble it. So when the warrior’s boy was born he was found to have the ways of a bear, and to become more and more like that animal the older he grew. The boy, quite aware of the resemblance, often went away by himself into the forest, where he used to pray to the Bear Spirit.

On one occasion, when he was quite grown up, he accompanied a war party of the Pawnees as their chief. They traveled a considerable distance, but ere they arrived at any village they fell into a trap prepared for them by their enemies, the Sioux. Taken completely off their guard, the Pawnees, to the number of about forty, were slain to a man. The part of the country in which this incident took place was rocky and cedar-clad and harbored many bears, and the bodies of the dead Pawnees lay in a ravine in the path of these animals. When they came to the body of the bear-man a she-bear instantly recognized it as that of their benefactor, who had sacrificed smokes to them, made songs about them, and done them many a good turn during his lifetime. She called to her companion and begged him to do something to bring the bear-man back to life again. The other protested that he could do nothing.

“Nevertheless,” he added, “I will try.” If the sun were shining I might succeed, but when it is dark and cloudy I am powerless.”

The sun was shining but fitfully that day, however. Long intervals of gloom succeeded each gleam of sunlight. But the two bears set about collecting the remains of the bear-man, who was indeed sadly mutilated, and, lying down on his body, they worked over him with their magic medicine till he showed signs of returning life. At length he fully regained consciousness, and, finding himself in the presence of two bears, was at a loss to know what had happened to him. But the animals related how they had brought him to life, and the sight of his dead comrades lying around him recalled what had gone before. Gratefully acknowledging the service the bears had done him, he accompanied them to their den. He was still very weak, and frequently fainted, but ere long he recovered his strength and was as well as ever, only he had no hair on his head, for the Sioux had scalped him. During his sojourn with the bears he was taught all the things that they knew—which was a great deal, for all Indians know that the bear is one of the wisest of animals. However, his host begged him not to regard the wonderful things he did as the outcome of his own strength, but to give thanks to Tiráwa, who had made the bears and had given them their wisdom and greatness. Finally, he told the bear-man to return to his people, where he would become a very great man, great in war and in wealth. But at the same time he must not forget the bears, nor cease to imitate them, for on that would depend much of his success.

“I shall look after you,” he concluded. “If I die, you shall die; if I grow old, you shall grow old along with me. This tree”—pointing to a cedar—“shall be a protector to you. It never becomes old; it is always fresh and beautiful, the gift of Tiráwa. And if a thunderstorm should come while you are at home throw some cedar-wood on the fire and you will be safe.”

Giving him a bearskin cap to hide his hairless scalp, the bear then bade him depart.

Having arrived at his home, the young man was greeted with amazement, for it was thought that he had perished with the rest of the war party. But when he convinced his parents that it was indeed their son who visited them, they received him joyfully. When he had embraced his friends and had been congratulated by them on his return, he told them of the bears, who were waiting outside the village. Taking presents of Indian tobacco, sweet-smelling clay, buffalo-meat, and beads, he returned to them, and again talked with the he-bear. The latter hugged him, saying:

“As my fur has touched you, you will be great; as my hands have touched your hands, you will be fearless; and as my mouth touches your mouth, you will be wise.” With that the bears departed.

True to his words, the animal made the bear-man the greatest warrior of his tribe. He was the originator of the Bear Dance, which the Pawnees still practice. He lived to an advanced age, greatly honored by his people.

The story tells of the initiation of a bear medicine man. The young man died and was revived by the animals, and through this his real mission in life was revealed to him. When Native Americans who live in bear country kill a bear, they conduct a similar revival ceremony so that the spirit of the bear can reincarnate.

The Bear Spirit Posture

A bear draws its immense power out of its middle region, out of the solar plexus, the power chakra that is located between the navel and the heart area. One can witness such power when observing bears. Bear shamans also draw their energy from this center, which Hindus call the manipurna chakra. “The yogi who concentrates on this chakra achieves continuous siddhi and is able to find hidden treasures.4 He is freed of all sickness and knows no fear of fire,” says Sivananda (Friedrichs 1996, 53). Carlos Castaneda (1925–1998) also describes the solar plexus as the source of the shaman’s magical power.

The first bodily reaction to sudden shock or panic is experienced in the ganglia of the sympathetic nervous system behind the solar plexus. The feeling can be described as a “punch in the gut.” On the other hand, it can be experienced as a sudden surge of energy, which enables the shocked person to react instinctively and overwhelm the enemy in an instant or save someone’s life by courageous action. Shamans or mediums often feel that their solar plexus “opens” during their popularly termed OBEs, or out-of-body experiences. The “spirit body” or “subtle body”—according to the testimony of spiritual mediums—floats on a gossamer-thin “silver string” coming out of this energy center and can experience nonsensory dimensions (Storl 1974, 206).

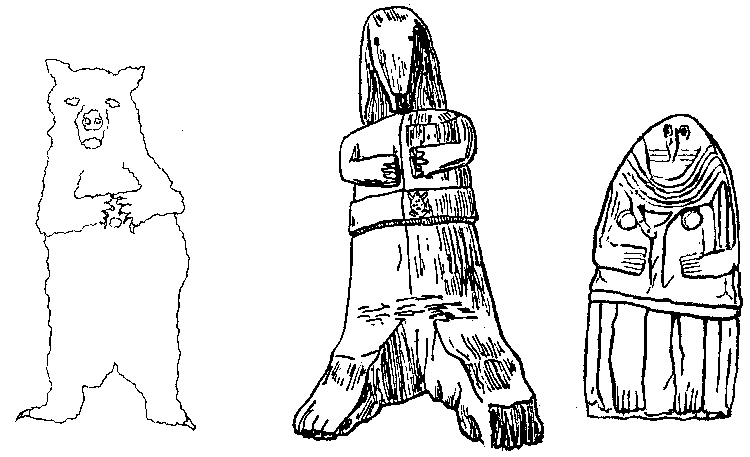

Left: Bear spirit posture (drawing by Nana Nauwald, 2002) Middle: “Shaman in contact with the bear spirit” (Nivkh wood carving, Siberia). Right: Menhir, Saint-Germain-sur-Rance, France, approximately 2000 BCE.

Elaborate research carried out by cultural anthropologist Felicitas Goodman shows the connection of this chakra with the bear spirit and its healing power. She investigated states of trance and different body positions taken by shamans when they connect with a god or an animal spirit. Each spirit being requires that the human take a different body position when seeking contact. The “bear position”—also called the “healer position”—makes it possible to open the soul for the bear spirit and let its healing energy flow in; it is usually a standing position. The fingers are rolled in and held over the navel so that the knuckles of the index finger touch slightly. The knees are slightly bent, and the feet are parallel to each other and planted solidly on the floor (Goodman 2003, 165). This typical bear position can be verified in statues and carvings in many historical and modern cultures.