Chapter 8

The Vital Spirit of the Vegetation

Tell us of the birth of Otso!

Was he born within a manger,

Was he nurtured in the bathroom

Was his origin ignoble?”

This is Wainamoinen’s answer:

Otso was not born a beggar,

Was not born among the rushes,

Was not cradled in a manger;

Honey-paw was born in ether,

In the regions of the Moon-land,

On the shoulders of Otava,

With the daughters of creation.

Kalevala, Rune 46

The archetypal imagination that linked the cave, the bear, and the woman in a large mythological web lived on beyond the hunters of the Old Stone Age. This god-like woman, primeval mother of all game, healing plants, and shamans, lived on with the first sedentary farmers and became Mother Earth, whose cornucopia showers onto the fields filling them with grains and all of the other fruits of the field.

Mother Earth was, to express it in modern language, the personification of nature itself. Primeval peoples, especially the matriarchal first planting peoples, would hardly have understood our word “nature,” which was a word created much later by Latin Church scholars. They did not think abstractly, but in pictures. They saw their world as absolutely alive and animated. That which we noncommittally call nature was for them the Great Mother, the one who bears and nourishes all of life, but also the mother of death who takes her creatures back, mourns, and weeps for them, only to bear them once more anew in the great cycle of all that is.

The first planters, including the megalithic farmers in Europe, scratched open the virginal skin of this great mother and planted bulbs or sowed grains into her—a process that they saw as a sort of sexual procreation.

Bloody Sacrifices

Because Mother Earth was a woman who was to become pregnant and bear many children, she needed a lover and sire who was worthy of her. And who would be more suitable than the wild bear, who goes in and out of her subterranean realm with impunity? As has been mentioned earlier, already the old hunters regarded bears as potent, libidinal, and fertile. It was only fitting that the bear was integrated into the Neolithic fertility cult as the son and lover of the goddess. Of course, his relationship with her is, in fact, downright incestuous, but, after all, we are dealing with gods who are often allowed to do things forbidden to mortals.

Contrary to the self-domesticating human beings with all of their artificial behavior, bears live in harmonious unison with nature and its seasonal rhythms. They appear with the balmy breeze and first green in the spring and disappear when the leaves fall and the vegetation retreats into the root realm below the ground. Bears follow their drives just like wild human beings did, who were still untouched by civilization. For this reason, the bear was suited to be honored by many tribes as their primeval forbear. Bears are still bonded with pristine, unbridled fecundity, with the pure beginnings of life. Because primitive and primal are regarded everywhere as potent and fertile, the bear is the natural fitting paramour of the goddess.

“Fertility cult” is a favorite but fairly nebulous concept often used by anthropologists. It refers to the rituals regarding the welfare of humans (and animals) and their “daily bread” (in reality, in earlier times, it was the daily mush as bread was not yet baked). In order to ensure prosperity, magical help from the old, experienced clan members who knew about the secret of the goddess and her lover was necessary. So it followed that, amid the first sedentary farmers, a caste of priests developed to carefully guard their knowledge. Their purpose was to influence the goddess with strict rituals, ceremonies, rites, and sacrifices during which often plenty of blood flowed. These priests even often sacrificed a son or lover for the goddess so that his blood—this precious red juice of life—would give her womb new strength. They had observed that blood and fertility are obviously connected: blood flows when women lose their virginity as well as during birth, and the beginning of menstruation is the beginning of fertility for women just as menopause presages the end of fertility. These observations supported their conviction about blood and fertility in a wider dimension.

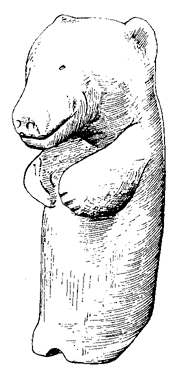

Sandstone figure from a Neolithic field of graves near Tomsk, Siberia

It is possible that late Neolithic planters, lake dwellers, and megalithic farmers sacrificed bears in elaborate rites believed to ensure fertility for humans and fields. There is also reason to believe that young bears were raised in villages as honored guests and then sacrificed, as eastern Siberian tribes still did until recently. In northern Europe, bear figures carved into amber were found from this time period; in the Balkans, terracotta figures of bear-headed women nursing bear children1; and in many places, especially in the late Neolithic lake dwellings surrounding Swiss lakes, well-polished bear teeth with many holes drilled in each one.

Soon, though, other animals superseded the bear as lovers of the great goddess, such as bulls, billy goats, boars, and rams. Especially powerful, drooling bulls, as the very incarnation of male virility, were favored as a sacrifice. (Spanish bullfights with their culminating sacrifice are remnants of such archaic sacrificial rites.) Despite its wild nature, a bull is a domesticated animal and therefore more accessible to farming peoples. With remarkable virility, a bull sires an entire herd. In some of the old agricultural cultures that were known to be matriarchies, even young men in their prime were sacrificed within the framework of orgiastic festivals.

“Straw-Bear” and “Pea-Bear”

Even though fertility cults took on new forms as times changed, they could not completely displace the ancient bear cult. Even in modern traditional farm culture, the bear plays a role as a bringer of fertility. In this context, anthropologists describe the bear as a “vital spirit of fertility.” Northern Germanic peoples also called Thor, the god of farmers, by the nickname “Bjørn,” which means “bear.” Thor roars over the fields in a wagon pulled by two goat bucks when there is a thunderstorm, thus bringing fertility to the fields. In the countryside in Sweden, it is still said, when the wind blows over a field of grain, “there goes the grain bear.” In Saxony, the grain bear is believed to be the son of the grain mother. In many places, the “bear” is believed to be in the last sheaf that is cut and bound during the harvest. In lower Austria, the “bear”—usually a young man dressed as a bear—comes to the farm that finished harvesting last. Such harvest customs are even still widely practiced in Europe despite modern machinery.

At the time of the winter solstice when, during the twelve days of Christmas, the cosmos revitalizes the earth and the new light is born, festivals of fertility were also traditionally celebrated. All of the festive foods, the nuts and apples and cakes, represent—in the language of symbolism—the renewal of life, the seeds for new harvests. Cakes and cookies were already baked in pre-Christian times in the Old Nordic-Celtic midwinter festivities. Motifs of men and women as well as boars, roosters, the Christ child, stags (also an ancient symbol of the sun), oxen, white horses, or bears in favorite festive breads and cakes developed into baked Santa breads, as one still finds in northern Europe at Christmastime. These festive breads were usually baked from the grain of the last sheaf. They represented the concentrated power of life sprouting out of the earth and were given, just as apples and nuts, as nourishment for the dead. They were offered to the ancestors, who were waiting in the depths of the earth under the protection of the great goddess until they returned to life on earth.

The grain mother, a typical symbolic Christmas cookie

On these holy nights in Europe at Christmastime (also the winter solstice), here and there a “bear” appears, or some other wild animal, usually accompanied by a holy man, such as Saint Nicolas, or by a servant, such as “Servant Ruprecht” (German Knecht Ruprecht) in Austria. Here again, the bear is associated with fertile prowess, just as the hazelnut rods that the old man carries are. Originally, this rod of life was used in a playful way on women and cows so that they would be fertile; there are still festivals today in which the young men of the village run around and playfully “beat” the young women with hazelnut rods on the holy nights of midwinter.2 On these nights in which the spirits promise fertility, treats used to be offered to the bears. In Norway, the leftovers from the Christmas feast were brought into the forest for the bears; in northern Bohemia, the leftovers were tossed under the fruit trees for them.

But especially during the wild post-Christmastime, the time of fasting, but more traditionally the time of carnivals and bawdy fooling around, the old bear spirit appears. The Church and the Enlightenment, which both agitated against this ancient survival of heathen fertility festivals, had their hands full trying to curb this wild, often obscene behavior.3 But it did not work. Even today in many areas in Europe, young men with blackened faces, wild animal masks, and furs run around at night and ritually tease the young women, who are more than happy to play along.4 During this time of year, the powerful, uninhibited bear comes very much into its own. It represents the wild energy beyond civilized manners and mores without which sexuality and proliferation are hardly possible.

Long ago, in most of Europe, it was custom to thrash all of the grains before fasting time. The young fellow who thrashed the last grain sheaf, or pea sheaf, was masked and wrapped in straw and chosen to be the pea-bear (or straw-bear, oat-bear, or rye-bear).5 A “gypsy” or bear trainer led him through the entire village with loud music and tra-la-la where he danced on all fours and scared the women. He was brought into the stables to drive out wicked (invisible) witches and scratch at cracks in the walls with his claws to drive out bad spells that may have been put into them. One of the customs was to have the pea-bear refuse to enter a jinxed stable until the farmer gave his trainer a coin or until he recited the right phrase. The pea-bear also showed a lively interest in the supposed flirts of the village because he also symbolized manly drives that are hard to rein in. In some villages in mainland northern Europe and England, the pea-bear simply trotted from house to house asking for alms.

In many places, the pea-bear was brought to court after his rounds. He was accused, inevitably found guilty, and “beheaded,” at which time pig bladders hidden under the pea-bear’s disguise and full of blood were emptied. In other places, a bear made of straw was burned as a symbol of the old winter leaving to make way for spring. In even other places, there were “bear hunts” during this fasting time. A man dressed as a bear was hunted by a pack of “dogs” and a bunch of other carnival fools and “slain.” In the Rhineland, a bear, as the embodiment of the wild, crazy time, roars and romps for the last time on Ash Wednesday. Women pluck some of the straw out of his fur coat to place in the hens’ nests for fertility. Then, the bear’s fur coat is also burned to ashes. (In medieval Rome, a real bear is supposed to have been shown around like this and then ritually killed.)

The bear of the fasting time (Lent), doing the rounds in a Bohemian village

In some of the regions in French-speaking Switzerland, the bear appears once more as a May Bear or Pentecost Bear. For example, in Ragaz, Switzerland, a six-foot (two-meter) figure decorated with flowers and colorful ribbons is paraded through the streets by loud youths. This “bear” also has an inglorious end and is tossed into the river. Once again, civilization and law and order triumph over wildness and chaos, but only after the beast has bestowed its power and blessings for fertility. And finally, the old Scandinavian and Russian wedding custom should be mentioned, in which a hooded guest represents the honey-loving bear and crawls around on all fours during the festivities!

These customs, which live on as superstition and are barely understood, are surely remnants of the first sedentary peoples’ religions. The decorated young bride symbolizes the great goddess, and her companion, the wild bear, is the bringer of fertility. As is shown in so many of the folk tales, its death is not its end but a necessity for its transformation. By being sacrificed, it is freed of its animal existence, and, as a stately groom, it celebrates its resurrection as a human being.

In the year’s cycle, the bear, the companion of Mother Earth, symbolizes death and rebirth in harmony with the sun cycle. It is sacrificed into the earth, fertilizes the earth, and is then transformed into new life. The mystery dramas of antiquity (ritually celebrated plays) of the great goddess—Ceres, Cybele, Isis, Nana, and so on—and her mistreated lover and son—Adonis, Attis, Tammuz, Osiris, Baldur, and so on—are a distant echo from Neolithic farming cultures. They even live on, changed beyond recognition, in modern decadence, detached from the moist, fertile earth and cosmic rhythms: Who has ever thought about the deeper meaning of the Elvis Presley cult, for instance? His house, Graceland, where he apparently still appears, continues to be besieged by hysterical fans.

Baby, let me be your teddy bear.

Put your chain around my neck,

and lead me anywhere.

Oh, let me be your teddy bear.

Elvis sang this refrain while gyrating his hips slowly to the rhythm, as if he had a girl in his hands and not his guitar. But, as he said himself, it was always his “mom” who he worshiped.

Even Christianity shows some heritage of this Neolithic imagination. God’s mother’s son is sacrificed in a bloody ritual—his flesh and blood are our bread and wine. His mother weeps over him, and his body is put into a grave with a heavy rock closing the entry. The stone is later rolled away, and he is resurrected and glorified. The first witness to this was the eternal woman.