Chapter 9

The Bear King of the Celts

Al primo die febbraio l’è fuori l’orso della tana;

se l’è nuvolo dall’inverno siamo fuori

e se sereno per quaranta giorni si ritorna dentro.

(On the first day of February, the bear comes out of his cave,

If the sky is overcast, winter is over.

But if it is sunny, there will be forty more days of winter.)

Almanacco del Grigioni Italiano, 1937

The warring cattle nomads came to Europe from the West Asian steppes. Their shiny bronze swords and battle-axes, but especially their battlewagons drawn by horses, terrified the late megalithic hoe farmers in Europe. The haughty invaders brought along herds of cattle, of which ownership was considered the very epitome of wealth. They also brought warring gods, and they worshiped light. Not even willing to give their bodies back to the earth, they burned their dead to ashes.

These Indo-European tribes, whose descendants included the Celts, soon subjugated all of Central Europe. They began to extract iron ore from the earth and forge iron swords; their rule ranged all the way to the Atlantic coast, to Britain and to Spain. Their warriors, who honored the strong, unflinching, and fearless bear as their totem, took over the earthen fortresses of their predecessors and used them for banquets. Their priests, who honored the sensitive, nervous stag as their totem, retreated into the forest and became known to us as “wise hermits,” or Druids. These Druids, adopting the stone circles and menhirs that had been built in honor of the earth goddess, recognized the cosmic rhythm and order, including the summer and winter solstices, by observing the shadows thrown by the stones.

For farming peoples, it is a matter of survival to know the right time to sow the fields, when to bring the animals to pasture, when to harvest. The Celts mixed with the peoples and came under the influence of the time-measuring stones and the great goddess. They recognized the daughter of the heavenly goddess, Dagda, the white goddess, in the earth mother. The shadows thrown by the megalithic stones measured her steps as she tread upon the earth, the phases in her life: her appearance in the spring, her marriage in the joyful month of May, her birthing in the early fall with the fruits of the earth, and her disappearance into the gray fog in the fall.

Celtic bear amulet from Lancashire (Northern England, made of anthracite/jet)

Warrior fighting a bear-like monstrosity

The white goddess chose the first of the warriors, whose totem was the bear, as her hero and lover. She chose the chieftain of the tribe as only a chieftain, the bravest and best among the people, was worthy of her. The bear was the king of the animals, so it only followed that the king of the people, her spouse, would also be called “bear.” Artur, Arto, Mato, Matus, and similar Celtic names represent the terrifying king of the forest. Thus, they named their tribal rulers as such, from King Math of the Irish with his magic powers to the king of kings, King Arthur of the Round Table.

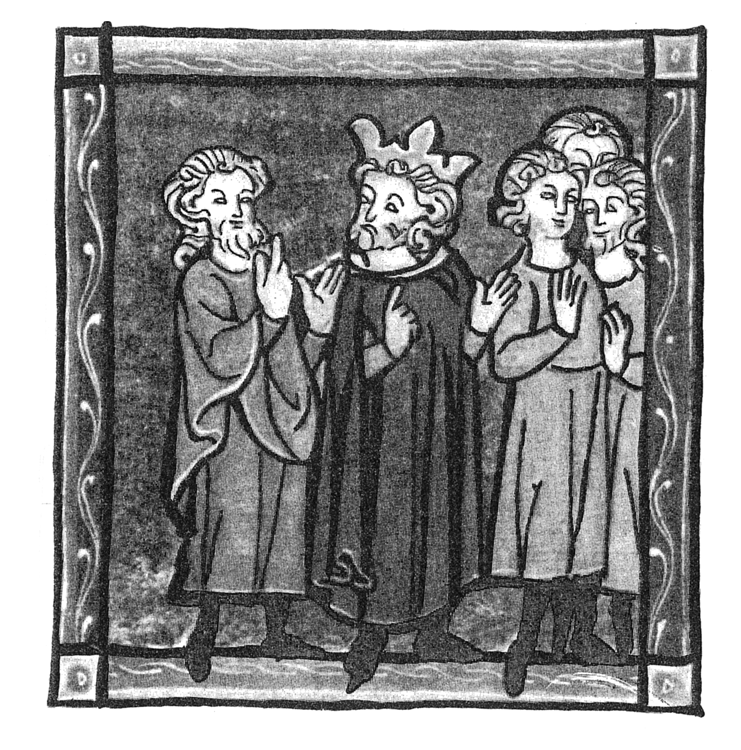

King Arthur with Merlin (Arnulfus de Kay, Plusieurs Romans de la Table Ronde, 1286)

The Celts saw the royal loins, male potency, as a prerequisite for ensuring the thriving and fruiting of the earth. The bear was the plow and the goddess was the virginal furrow. If he became old and weak, the fields and herds would also decline; then, it was time to dethrone or ritually sacrifice him so that the merciless fair lady could choose herself a new king.

Just like the bear that disappears into a cave when the green of the summer has passed, the king also disappeared into the “otherworld,” the realm of the dead, only to come back later, completely rejuvenated. Even if he appears to die, the king is immortal. Rex quondam, rexque futurus, the once and future king, refers to King Arthur, the bear king, who comes back again and again to love the goddess anew. This pre-Christian culture seems strange to us today, but a lot of these ideas are still alive. Let us have a look at how diverse country customs and festivities have their roots in the cult of the white goddess and her bear lover.

The Wheel with Eight Spokes

The Celts divided the rural year into eight phases and celebrated the transition from one to the other with fire festivals and sacrifices. The four solar cardinal points, the so-called quarter days—the fall equinox, the spring equinox, and the longest and shortest days—divided up the year. The four segments were then halved, resulting in the cross-quarter days: the full moons of February, May, August, and November.1 In this way, the wheel then had eight spokes. The goddess danced over the earth in eight steps.

These so-called witches’ days had special meaning for the Celts. They were in-between times, times of transition, times in which the old was passing but the new had not yet completely taken hold. During these short pauses, when everything was hanging in the balance, ghosts, gods, elves, and other ethereal beings from the otherworld could slip into human beings, take on their shape, and tell the future. The bear, who needs no calendar stones to recognize cosmic rhythms, celebrated the festivals of the goddess in his own way.

The Festival of Light

The beginning of these sacred festivals took place during the February full moon. Irish Celts called this festival Imbolc. Although northern climates are still in a frozen winter state at such a time of year, the days slowly are getting longer and the sap unnoticeably begins to flow in the trees. In this new light, the goddess appears as a beautiful maiden of light. In pre-Christian times, it was called the Festival of Lights, and, in Christian times, it became known as Candlemas Day (in the United States, Groundhog Day). Spirits of fertility and nature spirits were believed to come out of the earth with the goddess of light, who in other northern European countries was known as Birgit (from Indo-Germanic bhereg = radiant, shining). The bear, the goddess’s furry, divine companion, also ventures out from the earth at this time.2 According to legend, Bruin, still quite stiff and drowsy, sticks his nose out for the first time on this day to see how far spring has come along.

Celtic peoples greeted Birgit with festive fires and consulted oracles. The goddess of light was so adored as a muse, poet, healer, and magician that not even the Christians wanted to discontinue the festivities honoring her. After renaming the festival Candlemas, household candles that would be used for religious purposes for the rest of the year were blessed on that day.

Some country folk still shake the trees on Candlemas to wake them up and tell the bees, “Bees, be happy, for today is Candlemas!” “If the sun shines on Candlemas, it will be a good year for the bees” is a saying in the countryside in England. On this day, it is time to take down the holly and pine branches that were winter decoration. Traditionally, by the time Candlemas comes around, the threshing and spinning should all be done because the new grain bear, or pea-bear, comes around (as has been described earlier) and brings new fertility. The day is also traditionally seen as an oracle day—who will marry, who will die, and how the harvest will be. To find out how much longer the winter will last, the animals that have been hibernating in the ground are observed. Foxes and badgers are observed as substitutes for bears. In many northern European countries, this saying is known: “If it is warm and sunny on Candlemas Day, the bear has to stay in his cave for six more weeks.” According to this saying from Baselland, Switzerland, “As many hours as the bear can sun himself up above, so many more weeks of winter” (So maengi Stund der Boer z Liechtmess dr Doope cha sunne, so maengi Wuche wird’s no Winter) (Hauser 1973, 114). In France and England, the saying goes, “If the bear sees its shadow on Candlemas, it will have to go back into its cave for forty more days.” In the United States, the groundhog has taken over the role of the bear. After forty days, it will be spring equinox and then Bruin can really shake off his winter drowsiness and the bane of winter is broken.

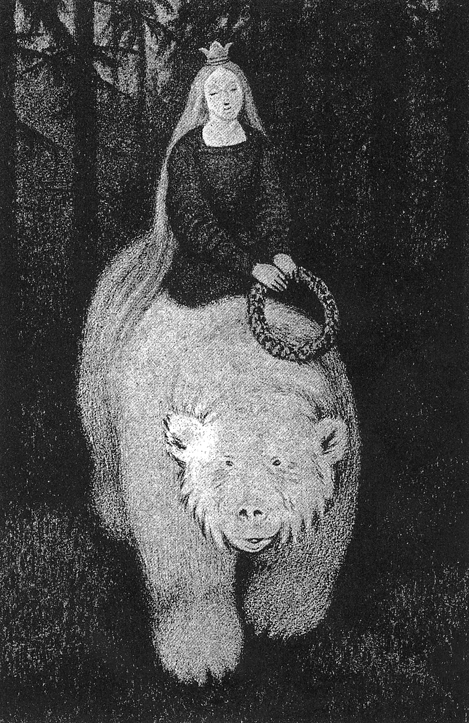

The spring goddess riding a bear

Bears, which bring fertility, and bees that produce beeswax out of which golden, shining candles can be made, are radiant Birgit’s favorite animals. In the colorful ways of country thinking, the two extremes belong together: massive, virile, lazy Master Bruin and tiny, chastely, industrious bees.3 Bees were especially admired because they draw the nectar out of the blossoms without destroying them. For the early Europeans, honey, which was not replaced by cane sugar until the seventeenth century, was the only sweetener. It was so sacred that it was given to the gods and ancestors as an offering, and only in the holy nights of midwinter were cakes sweetened with honey eaten as sacred food. The Indo-Europeans saw honey as a remnant of a long ago, golden age, when honey was the dew on the primeval world tree. It is truly a divine food for the chosen one of the white goddess, the honey-eating king of the animals in the forest, as well as for the king of the people. The king and his noble companions drank wine made of honey (mead), and the peasants, servants, and workers drank beer made of barley.

May Joy and August Fires

When nature begins to turn green again in the spring and flowers begin to blossom, when the sun shines ever warmer and the queen bee swarms out for her nuptial flight with her entourage, the goddess of nature also celebrates her wedding. When the hawthorn blossoms and the full moon in May light up the landscape, the goddess becomes the radiant bride of the sun god. In honor of the divine couple, young men and women dance around the maypole, which has been decorated with colorful ribbons, and fall in love with each other. The bears in the forest also fall in love in the joyous month of May if the female bears no longer have small bears with them. They romp around joyfully in flowering meadows. Their wedding lasts until the summer solstice, which the Christians named Saint John’s Day. Then the female bear is pregnant.

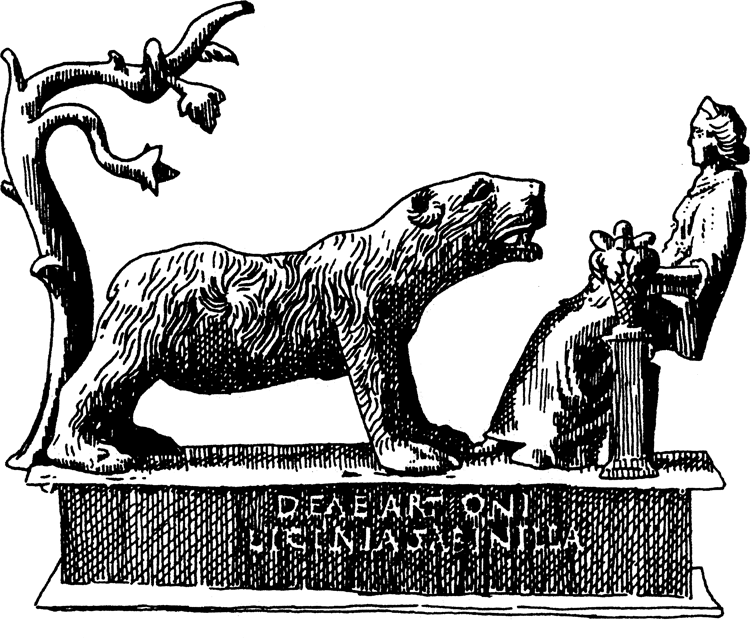

Forty days after the summer solstice, another magical point in time arrives: the fire festival Lugnasad (Anglo-Saxon Half-mass, Lammas = festival of the bread loaf) in the full moon days of August. Again, the bear appears, this time in the form of the last sheaf, as the grain bear. The goddess now appears as the mother of the grains. She is no longer a shy young maiden or freshly married bride. She is a matron whose cornucopia is over-abundantly filled with fruits and grains. We recognize her in the Dea Artio, the Celtic-Roman bear goddess, whose statue was found in 1832 in Muri, near Berne, Switzerland. She is sitting majestically on a throne, in front of her is her companion, a big bear, and she holds a full basket of fruit.

Dea Artio (bronze, from Muri near Berne, second century BCE)

For the Celts, the August fire was at the height of the summer. At this time, the goddess pours out her blessings—but she also already begins to retreat from the outer world and head back toward the otherworld again. Under the custody of the Church, this festival became known as Mary’s Assumption. At this time, when God’s mother leaves the earthly world, the herbs are at their peak as far as their healing virtues are concerned. In Alpine regions, country women and herbal healers bring a bouquet of healing herbs to be blessed during mass.

This is also the time of the so-called dog days, these hot, humid summer days when the grasses dry up, the water in the ponds evaporates or dries up completely, and nasty gadflies pester the animals in the pastures. They begin in late July when Sirius, the Dog Star, ascends above the horizon, and end in late August when Arcturus, the bright guardian of the bear, ascends. The bear guardian walks along near the oxen driver, Booetes, protecting the heavily laden wagon from the hungry Big Bear (Arctus Major), which is filled with grains and wine, gifts from the goddess. In any case, this is how the old Greeks saw it when they looked up into the August sky. Harvest time continues beyond the fall equinox. The bears in the forest also harvest as much as possible and celebrate regular eating orgies. They become sluggish and fat like aging lovers. Soon the time will come when the goddess lets them be hunted or calls them into her cave.

Modraniht (Mother’s Night)

The Celts called the November days Samain (Irish samhain; Gallic Samon; English Halloween). It is the time of year when the light begins to leave the northern climate, the birds flock and fly south, and the pasture animals return to the barns for the cold time of year. It is the time of the dead, the time of gray fog, of quiet, the time for hunting and butchering. The bears, these virile symbols of fertility, and the nature spirits descend down into the sphere of the roots.

The goddess, now seen as a wrinkled old woman, also descends into the netherworld; or, according to other Celtic versions, she turns on her husband, the sun-bear, sun-god, or sun-stag, and marries the god of the underworld, to reign in his realm of the dead and ghosts. (In the Celtic-Welsh tale of King Arthur, this motif also surfaces: Sinister Mordred wounds the bear king fatally and takes his wife, the white fairy, Genevieve, as his mistress.)

In November, when the days grow ever shorter and darker and snow begins to fall, the bears in the forest become very drowsy. Soon, they will be sleeping cozily on soft beds of moss, dry grass, and leaves in their dens. They are not in torpor when they hibernate, such as, for example, rodents are. Their state during hibernation is more like a trance, similar to that of yogis in India when they go into samadhi (these yogis are also able to survive the entire winter in Himalayan caves, snowed in and without any nourishment). The bear’s heartbeat and breathing slow down during hibernation. Its pulse decreases to twelve beats per minute, and its body temperature sinks from 38˚C (100˚F) to 32˚C (89˚F). Bears do not excrete during this time and live from their fat reserves, so to say, on automatic pilot.4 In the spring, they weigh one third less than when they went into hibernation.

At the time of the winter solstice, or Christmastime, the bear cubs are born—one to three naked, blind, and helpless cubs, no bigger than puppies, weighing about 500 grams (one pound) each. The ancient Celts and Germanic peoples of the north called this sacred time of year Modraniht, “Mother’s Night”—a time when the new light, the child of the sun, is born deep in the earth. In earlier tales of Christ’s birth, he was also born in an underground stone cave and not in a manger.

For the early Europeans, it was evident time and time again that a bear’s life unfolded in synchronicity with the sacred yearly cycle. Just like the vegetation, bears appear in perfect harmony with the sun in the spring and disappear again in the fall. Bears are natural sons and daughters of the earth and have not removed themselves as far from their origin as the species Homo sapiens has. According to Rudolf Steiner, founder of anthroposophy, early humans in northern European latitudes were much more bound into the natural sun rhythms. They also wooed only in the early summer, and their children were born nine months later during the winter solstice. This pattern slowly changed as they became more independent of natural rhythms, and cultural acclimation (clothes, tools, institutions) replaced biological acclimation (pure instinct).

So far, we have mostly pursued ancient Celtic customs and their bear mythology because they are closer to native English-speaking, European cultural roots; however, other peoples also saw the bear as closely related to nature’s yearly cycle. For the Abenaki in Maine, for example, the seasons are mirrored in the life cycle of the cosmic bear: In the spring, the bear appears in the sky, and all summer long it is hunted by hunters with dogs. That is, the constellation of the Northern Crown (Corona Borealis) is a cave to the Abenaki; the shaft of the great wagon (the Big Dipper), Arcturus, and some of the stars in Booetes are the dogs. When the hunters shoot the bear down in the fall, the leaves in nature turn bloody red, orange, and yellow. The first snow is the fat of the bear dripping down to the earth when the hunters melt it down. After the heavenly hunters have eaten the flesh and put his bones back together in the right order, the bear comes back to life and goes into hibernation. In the spring, the eternal drama of the bear hunt starts over once again.

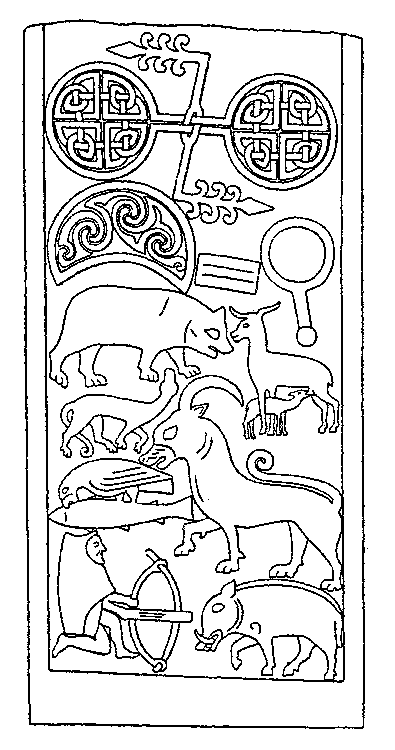

Animals, including the bear (Celtic Cross from Drosten, St. Vigeans, Forfarshire)