Chapter 11

Berserkers and Guardians of the Threshold

The berserkers are ready,

Wolves will escort them,

Whether Middle Ages

Or modern times, is all the same.

They came once more from up above

But this time not to run riot,

Instead to give their power

For the earth and Life on earth.

The berserkers are back again,

So that the earth can come back into its own,

They are bringing all the gods along

And dedicating themselves to Mother Earth.”

Norbert J. Mayer, from Die Berserker sind angesagt! (author’s translation)

Positivist scientists would hardly join company with primitive peoples and their storytellers in their belief in a realm of light under the surface of the earth, inside the mountains where gold and precious jewels are strewn all over, where white stags with golden antlers graze peacefully near bears, and where the dead and unborn dance lovely round dances together. However, those who research the vast depths of the soul presume we are not dealing with a material, geographical place that can be found by following a map, but a realm in our unconscious that is usually blocked off from our daily consciousness. And there, under the surface, is the very real primeval fountain of all vitality, beauty, and wisdom—precisely such riches of the soul that are waiting to be discovered—there in the realm where the bear is at home.

Only great shamans, noble spirits, and gods, such as Krishna or Zalmoxis, are allowed to enter the cave and find treasures on the sunny meadows of the otherworld and then return to this world. Terrible “guardians of the threshold” keep those who have no business in these realms at bay. Fire, poison, and gall-spewing dragons and sphinxes, hell hounds with huge red-glowing eyes, or giant bears with their paws raised and jaws wide open guard these treasures from wanton seizure. (For the people of ancient times, these monsters were real beings—psychoanalysts see them as psychic repressions or fears that have taken form in the imagination.)

The devil is also never far away from such mysterious places. In Goethe’s most well-known work, learned Dr. Faust conjures the son of Mother Night, the spirit of hell, Mephistopheles. He turns out to be the ancient “earth daemon” that has command over all earthly treasures and possesses all the wisdom of the earth. Justifiably, the poet has him appear as a black poodle—in many old religions, a black dog is the guardian of the threshold to the netherworld. However, in the old medieval tales that tell about the excessive life of corrupt Dr. Faust, Mephistopheles usually appears as a black, or fiery, bear, or a bear with a human head—who comes out from behind the fireplace.

Anyone who wants to reach the hidden hoard of treasures has to deal with this bear. The hero must be willing to put aside the false pretenses and phoniness of the civilized world and must bathe in dragon’s blood or slip under a bearskin. He must be pure-minded, be uncorrupted, and have clear instincts, like a bear or a “noble savage.” This is the only way to find the precious gem of life. This is the only way to save, or even be able to save, the “maiden in distress” who is “captured” in the depths of the soul.

This is the heroic path that the young warrior embarked upon in the following story, “Bearskin.”

Once upon a time, there was a young fellow who signed up for the military, was very brave, and was always the first one forward when the bullets flew. Things went very well as long as there was a war somewhere. But when peace came, he was dismissed and his commander told him he could go wherever he wished. His parents were dead, and he no longer had a home to go to, so he looked up his brothers and asked if he could stay with them until another war started. But his brothers were hard hearted and told him to move on. “There is nothing for you here! We can’t use you around here. Move on and find a way to make it on your own!” they said.

The soldier had no other possessions than his gun. So he shouldered it and took off out into the world. He came upon a big area of heather and moorland where nothing was to be seen but a ring of trees. He sat down under the trees and mused about his fate. “I don’t have any money,” he thought, “I haven’t learned anything but the trade of war, and now that we are living in times of peace, it looks like I will starve.”

Suddenly, he heard a boom and just as suddenly an unknown person stood there in front of him. He had a green jacket and was quite smart looking, although one of his feet was a horrible-looking horse’s hoof. “I know what you need,” said the man, “you shall have money and property, as much as you want, but first I have to know whether you are afraid so that I don’t spend my money for nothing.”

“A soldier and fear, how does that go together?” asked the soldier, “You can put me to the test.”

“Well, then,” the man answered, “look behind you.”

The soldier looked behind him and saw a big bear that was trotting straight toward him, grumbling loudly. “Look at that,” the soldier called out, “I will tickle your nose so much you won’t be grumbling anymore!” He grabbed his gun, aimed, and shot the bear so that it dropped dead in an instant.

Bearskin, bear, and the devil

“I see that you certainly do not lack courage,” the stranger spoke, “but there is one other condition that you must fulfill.”

“If there is no damage to my soul, I will,” said the soldier, who very well knew who was standing in front of him, “otherwise, I will make no deal.”

“You will see,” answered the man with the green jacket, “you may not bathe for the next seven years, may not comb your hair or beard, not cut your nails, nor say the Lord’s prayer. I will give you a jacket and overcoat that you have to wear during this time. If you die within the seven years, you are mine. But if you stay alive, after seven years you will be free and will be wealthy for your entire life.”

The soldier thought about his needy situation and decided to accept the offer. The devil took off his green coat, gave it to him, and said, “As long as you wear this coat and search the pockets, you will always find a hand full of money.” Then he skinned the bear and said, “This will be your overcoat and also your bed because you have to sleep on it and use no other bed. And because of this overcoat you will be called Bearskin.” The devil then disappeared.

The soldier put the jacket on, reached right away into a pocket and found that things were as had been promised. Then he put the bearskin on, went out into the world, and left nothing undone that did him some good and didn’t do the money quite as much good. During the first year, it went quite well, but already in the second year he looked like a monstrosity. His hair almost covered his whole face, his beard looked like a piece of coarse felt, his fingers had claws, and his face was so packed with dirt that if one had sown cress into it, it would have sprouted. Anybody who saw him ran away. But because everywhere he went he gave the poor money to pray for him that he would not die during the seven years and because he paid up front for everything, he always found room and board. In the fourth year, he came to a lodging where the innkeeper did not want to let him stay. He did not even want to give him a place in the stall because he was afraid his horses would get spooked. But when Bearskin reached into his pocket and pulled out a handful of ducats, the innkeeper softened and gave him a room in the far back, but he had to promise to not show himself lest his inn get a bad reputation.

As Bearskin sat there alone in the evening and was wishing from the bottom of his heart that the seven years were over, he heard loud crying in the room next to his. He had a compassionate heart, so he opened the door and found an old man sobbing and wringing his hands. Bearskin came closer, but the man jumped up and wanted to flee. When he heard a human voice, he sat back down, and, with his friendly manners, Bearskin convinced him to tell him the reason for his grief. Bit by bit, he had lost his wealth and he and his daughters had to live in utmost poverty. He could no longer pay the innkeeper and was soon to be sent to prison. “If that is all,” said Bearskin, “I have enough money.” He sent for the innkeeper and paid the old man’s debts. Then he gave him a bag of gold to put in his pocket.

When the old man saw that he had been saved from his dire state, he thought about how he could thank Bearskin for his help. “Come with me,” he said to him, “my daughters are very beautiful. You may choose one as your wife. When she hears what you have done for me she will not refuse. You do look mighty strange, but she will get you nice and cleaned up.”

Bearskin liked the sound of that and he went along. When the eldest saw him, she was so shocked that she screamed and ran away. The second daughter stayed put but after looking him up and down quite thoroughly, she asked, “How can I accept a man who no longer has a human form? I liked the shaved bear even better that was once here pretending to be a man—at least it wore hussar’s cloak and white gloves. If it were only that he is ugly, I might be able to get used to that.”

But the youngest daughter said, “Dear father, if he helped you out of your troubles, he must have a good heart and your promise must be kept.” It was a real shame that Bearskin’s face was so caked with dirt and covered with hair; otherwise, one would have been able to see how his heart leapt for joy as he heard these words. He took a ring out of his pocket and broke it in two, giving her one half and keeping the other half for himself. He wrote his name in her half and her name in his half and asked her to guard it well. Then he took his leave, saying, “I must continue to roam for three more years. If I do not come back, you are free, because I will be dead. But pray to God to protect me and keep me alive.”

The poor young betrothed bride dressed in black, and, when she thought of her groom, tears came to her eyes. Her sisters mocked her. The eldest said, “Be careful, when he comes back and you want to give him your hand, he will hit it with his claws!”

The second sister said, “Be careful, bears love sweet things and if he likes you he might eat you!”

“You will always have to obey him,” the other one chimed in again, “otherwise he will growl.”

Then the other added, “Well at least the wedding will be fun because bears can dance well.”

The youngest sister remained silent and did not let them vex her. In the meantime, Bearskin traveled from place to place doing as much good as he could and giving generously to the poor while asking them to pray for him. Finally, at daybreak of the last day of the seven years, he went to the moor where the ring of trees stood and sat down again near the trees. It did not take long for a wind to come up, and there was the devil standing in front of him again with a peeved look on his face. He tossed Bearskin his old coat and asked him to give the green one back. Bearskin said, “We are not that far down the line yet. First you clean me up!” Whether the devil wanted to or not, he had to go get water and scrub Bearskin clean, comb his hair, and cut his nails. When he was done, Bearskin looked like a gallant warrior and was even more handsome than before.

When the devil disappeared, Bearskin felt very lighthearted. He went into town, bought a splendid velvet jacket, and took a coach drawn by four white horses to go to the house of his bride. No one recognized him and the father thought he must be a very high colonel, so he brought him into the parlor where his daughters were sitting. He had to sit between the two elder sisters; they poured him a glass of wine and offered him special tidbits to eat. They both thought they had never seen a more handsome man before. But the young bride sat in her black dress across from him and did not speak a word or even raise her eyes to look at him. When he finally asked the father if he could have one of his daughters as a wife, both of the elder sisters jumped up to put on their best dresses because each of them was smug and believed she would be the chosen one. As soon as the stranger was alone with his young bride, he put his half of the ring in a glass of wine and reached it across the table toward her. She accepted it, but, when she saw the ring in the bottom of the glass, her heart began to pound. She took her half of the ring that she wore on a necklace, fitted the two halves together, and saw that they fit perfectly. Then he spoke, “I am your promised groom that you saw as Bearskin. Through God’s grace, I was able to get my human form back.” He went over to her, hugged her, and gave her a kiss. Right then, her two sisters came back into the room. When they saw that the handsome man had chosen the youngest and heard that he was Bearskin, they ran outside in a rage. One of them drowned herself in the well, and the other hung herself on a tree. That evening someone knocked on the door, and, when the groom opened the door, he saw it was the devil with his green jacket on. The devil said, “You see, now I have two souls in place of your one!”1

The fairy tale tells of brave souls, who are not afraid of their own untainted, instinctive side, their “bear nature.” It also tells of those who are pure and humble, such as the youngest daughter, who dares to trust the bear and follow him through the dark labyrinth of life to achieve wholeness and the marriage of the opposites (the marriage of animus and anima, the male and female aspects of being). Souls like this will not be in need of anything. The devil is also not a problem for them because, after all, he is also only a servant of the pure and divine human being.

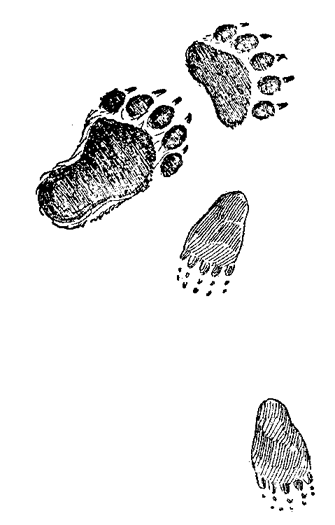

In this sense, it may very well be true that it is a sign of good luck to happen upon bear tracks, as believed by gypsies, Transylvanians, and many native peoples (who often hardly distinguish between internal and external reality).

Bear tracks

Interpretations

Let us go back now to the story of Snow White and Rose Red. The hero in this story is also a “bearskin.” The bear that appears so late at night at the cottage is in reality a young man who, after his trial as a wild animal, will discard his bearskin, return to society, marry, and come into his true inheritance. Depth psychology would see here the process of spiritual individuation, of finding one’s true being. In most Western European cultures, the true being of a young man, the innermost noble spirit, was traditionally usually seen as a prince. It is his destiny to free the maiden, who symbolizes the human soul, from prison or some other distress, marry her, and rule the country—symbolic for human life—with wisdom and justice as the king with her as his queen.

But before things get that far, a drama happens. The ugly lower self, the ego that feels shortchanged—this godless dwarf—is envious of the higher self and its treasures: the gold of wisdom, the pearls of tears spent while gaining clarity through catharsis, the gems of a crystal-clear spirit. The cunning gnome hexes the prince into a wild animal and steals his treasures. As a bear clothed in shaggy fur, the hero experiences the forest and wilderness—the dark world of the unconscious. He gets to know primeval, wild nature that is older than civilization. In this wilderness, he meets the female anima. She is his bride, the other half of his soul. But not until he overcomes the venomous dwarf—this appropriate symbol of lower, egotistical intelligence and materialism—can the bear cast aside his disguise. The soul then recognizes that its other half is waiting there beneath the rough exterior of the enchanted prince, and, through the marriage of the two halves, the human being becomes complete.

A cultural anthropologist would interpret the fairy tale, with regard to the cultural history of Europe, as follows: The three women, Snow White, Rose Red, and their mother, who live deep in the forest, represent the female trinity that was once prevalent in the entire Indo-European cultural area. Fairy tales that were recorded by the Grimm brothers and other collectors—and thus saved from being lost forever—contain many treasures of spiritual vision and wisdom common to the pre-Christian forest peoples of Europe, the Celts, the Germanics, the Slavs, and others. The three women are different aspects of the same one goddess. It is the goddess who reveals herself in the yearly changing of the seasons: as a white virgin; as the beautifully blossoming whitethorn goddess in the spring (Celtic Brigit); as the red goddess of the blood of life, summer warmth, and plentiful harvest; and as the dark lady of wisdom and death in the fall.2 We see here the ancient Paleolithic goddess of the cave, Mother Goose, in her changing appearances.

The bear, who finds shelter with the three women and from under whose fur pure gold shines, is the sun—is the sun god himself. Like the bear in the wilderness that holes up in a dark cave, the sun conceals itself mostly under the horizon in the winter (in northern climates), and a gray coat of fog muffles its light. In the spring, the bear tosses off its bearskin. When the whitethorn and blackthorn are in full blossom, the sun radiates like a young hero—bringing them to blossom. As Belenus (Celtic for “radiant, shining”), he woos the whitethorn goddess. His “brother,” who marries Rose Red, is the hero in the form of Celtic Lugh or Lugus (Celtic for “burning brightly”), representing the fiery sun in August that drives everything into ripeness and completion. As an old woman, as a grieving widow, the black goddess (Celtic Morrigan) accompanies the dying sun god in the late fall into the womb of the dark earth. On the darkest day of the year—the winter solstice—she bears the new light, the new sun, like a bear does its young.

Fairy tales are not clear cut; instead, they are usually ambiguous. Each interpretation can be correct. The shiny jewels guarded by a mystical bear not only exist in the womb of the earth or in the depth of the soul but also shine as stars in the high heavens—inaccessible to mortals. In the imagination of the alchemists and also some primitive peoples, crystals and precious gems are magically connected to the stars by invisible threads. According to the alchemical law “as above, so below,” precious jewels are reflections of the stars in earthly matter.

Both the depths of the earth and the distant heavens were regarded by archaic people as the otherworld, as the barely reachable “beyond,” as the realm of the gods and ancestors that is full of mystery. Bears and other guardians of the threshold watched over the thresholds to these worlds. Consequently, these peoples also saw bears in the heavens at night—shining, godly bears that roam along paths near the stationary North Star. We will now follow the star tracks of these heavenly bears.

The three-fold goddess (Renaissance representation, Vincenzo Cartari, Venice, 1674)