Chapter 12

The Heavenly Trail of Ursa Major

Ursa Major, descend, shaggy night

nebula-furred animal with those ancient eyes,

Star eyes,

your clawed paws break shimmering

through the thicket,

Star claws,

We keep vigil over our herds,

yet you hold us in your power, and we mistrust

your tired flanks and sharp,

half-bared teeth,

old Bear.

Your world is a pinecone

and you its scales.

I propel them, roll them

from the firs at the beginning

to the firs at the end.

I blow them, test them in my mouth

and grasp them with my paws.

From Invocation to the Great Bear by Ingeborg Bachmann, translated by Angelika Fremd

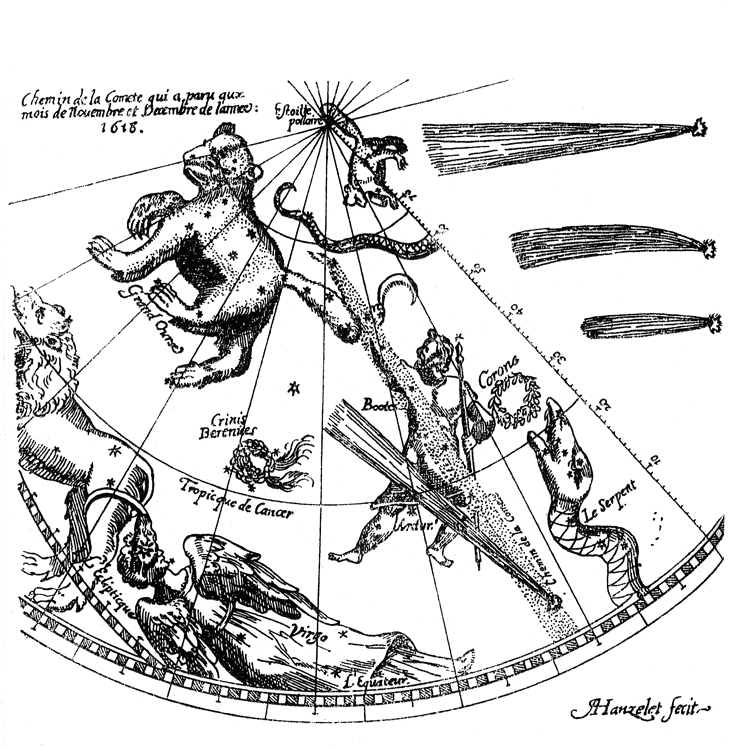

In the myths of the peoples of the northern hemisphere, one happens again and again upon the imagination of a big bear that roams around the North Star. We all know the constellation of the seven bright stars called Ursa Major (or the Big Bear, also known as the Big Dipper and in older times in northern Europe as “the Wagon”). It is easy to identify and often the first constellation that beginning astronomers learn. Close by, one can see the small bear, Ursa Minor, whose long tail points to the North Star.

Ursa Major and Ursa Minor

The Power That Moves the Heavens

In India, the seven stars in the constellation Ursa Major are called “the seven luminous ones” or “the seven rishis” who are gathered around God (the North Star) on the top of the world mountain (Mount Meru). According to an even older version, the Hindus speak of seven shining bears. The North Star is the hub around which the heavenly vault turns, and the bears represent the elemental power that makes the turning possible. They drive the stars that rise and set daily. They push and shove the wheel that turns summer to winter and back to summer, brings rain and harvest, but also wind and drought.1 These bears are identical to the Maruts, the storm gods that whirl around the god Shankar-Shiva with thunder and lightning bolts. The androgynous god of yoga, Shiva, sits in the quiet eye of the storm, and out of the unfathomable depths of his meditation the entire creation emerges. The North Star is the spring out of which the worlds flow, the place of birth, and the bears are the guardians of this cosmic womb.

For the ancient Germanic tribes, the North Star that was surrounded by vital bear power was not only a physical point of orientation but also a spiritual one. It is the tip of the conical firmament, the tip of the mystical mountain of glass; in the Edda, the North Star is called Leidharstjarna and in Old High German, Leitesterre, which means “leading star.” It is the star one looks for to avoid getting lost, to “get one’s bearings.” For some Siberian tribes, the heavenly bear appears in the constellations Booetes and Arcturus—the same constellations in which the ancient Greeks saw the oxen driver and the bear guardian. They call Ursa Major a huge elk that the hungry heavenly bear is chasing.

But no matter where the hunting peoples of the north see the divine bear in the starry sky, it is always the center of their religious life. The bear appears on earth, the middle world (of the three-fold heaven, earth, and netherworld), as a benevolent visitor. He is the cosmic shaman who connects the higher cosmic and lower earthly worlds. He is a higher being created by star power but at the same time the son of Mother Earth. Only to deceptive, everyday consciousness does he appear as a wild animal, bulky and clumsy and covered with fur. This ancient view lingers in the fairy tales that we sometimes tell our children. As we have seen, they also tell about the light and starry secrets of the bear. According to ancient Finnish belief, the heavenly bear descends from the northerly regions in the sky to the earth in a golden crib. Finnish reindeer herders describe dying as “mounting the bear’s shoulder,” what we know as “going to heaven.”

The Guest from the Twelfth Heaven

The Algonquian tribes lived as hunters and corn farmers in the northern forest areas of North America. They also worshiped the mystical bear and saw it in the four brilliant stars that form the square in Ursa Major (the dipper part of the Big Dipper). The three other stars that are the handle of the dipper, or for the ancient Germanic tribes the shaft of the wagon, were seen as three hunters with their dog, the star Alcor,2 who are hard on the bear’s heels. A star song of the Passamaquoddy, an Algonquian tribe that lives in Maine, goes like this:

We are the stars who sing,

we sing with our light;

We are the birds of fire,

we fly over the sky.

Our light is a voice . . .

We make a road for the spirits,

for the spirits to pass over.

Among us are three hunters

who chase a bear.

There never was a time

when they were not hunting.

We look down on the mountains.

This is the song of the stars.3

In the deepest wintertime, shortly after the January new moon, when it seemed that everything was going to petrify in the freezing cold, the Mohicans celebrated a twelve-day festival for the rejuvenation of creation. At that time, the cosmic bear, as a messenger for the Great Spirit, descended from the Twelfth Heaven down to the wintery world on earth. He took on the shape of a simple forest bear and appeared to a woman in a dream, revealing to her where he was hibernating. When it became known that a woman had dreamed the sacred dream, twelve hunters, under the leadership of a flawless bear ceremony master, set out to find the hibernation place. Without speaking a word, the hunters made their way through the deep snow in the forest. When they found the bear’s den, they waited—fasting and still not speaking—for one more day and night in the bitter cold. Only then did the ceremony master enter the den, greet the heavenly messenger as the lord of all animals, and ask him to follow him. Presumably, the master successfully contacted the bear telepathically because it is said that the drowsy bear followed the men willingly into the village. There, the divine guest was brought into a longhouse. The bear was tied to the center pillar and sent back to its star-lit, heavenly home when it was killed at the end of the all-night ceremony. The bear was then to tell the Great Spirit that everything on earth is in good order, that people are faithfully carrying out their duties, and that they deserve divine blessing.

The spacious sacrificial longhouse was covered with elm bark, built on an east-west axis, and seen as a reflection of the cosmos. The center pillar, on which the bear was killed, was seen as the world tree. The two fires that burned between the pillar and the two doorways symbolized the all-permeating duality: day and night, male and female, life and death. The bear on the martyr stake was the universal messenger, the being in which all dualities were obliterated. The seats in the longhouse represented the stars in the heavens. The ceremonial dances portrayed the movement of the stars and the life of the cosmic bear.

After the killing, the ceremony master skinned the bear with an obsidian knife, cutting in the opposite direction of that used for normally slain furry animals. Afterward, the bear’s body was carried out of the longhouse on the east side through the women’s doorway, the doorway of life, and prepared for a sacred communion meal. Neither salt nor vegetables were allowed in the broth. The dogs were shooed away. Under no circumstances were they to gnaw on the bones, which were all gathered and burned to pure ashes in the fire on the east side of the center pillar.

In the last four nights of the bear festival, as the full moon was approaching, the Mohicans danced until dawn. During this time, the festival escalated into an orgiastic, trance-like celebration. The bear that was now shining down from Ursa Major again was to watch over them. Through the festival, the necessary bear’s strength was given to the tribe so that all could grow and prosper for another year. Around 1850, the Mohicans were converted to Christianity. They were a defeated people, demoralized and decimated. No woman ever dreamed of the divine bear again—and, consequently, as the Mohicans came to say, compared to the height of their culture, hardly any bears roam the New England forests in modern times.

The winter bear festival of the Mohicans (painting by Dick West)

The Forbidden Name

The children who merrily play among the car junkyards, trailer houses, and army barrack–like prefab houses on the northern Cheyenne reservation play hopscotch and tag like any other children do. But sometimes they also play a bear game: A girl hides in a dark hole and the other children come as hunters. They have sticks and try to pry the girl out of the hole. They act like they don’t know what animal is in there and try to guess. A badger? A mountain lion? A prairie dog? A porcupine? They name all the animals they can think of. Only one animal they are not allowed to mention by name—the bear! It is a sacred animal, and its name is taboo. If one of the little hunters mistakenly calls out the bear’s name, the “enraged” little “bear” storms out of the cave to punish the excitedly squeaking and fleeing culprits.

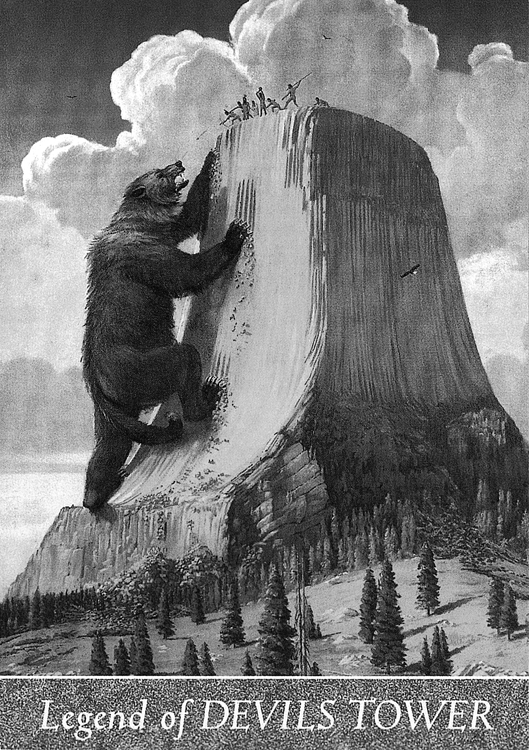

This simple child’s game has its roots in the mythology of the Cheyenne. In the myth, the godly bear storms down to earth to punish those who have called out his name and insulted him. Medicine man Bill Tallbull told the following story regarding this myth:

A very long time ago, a tribe had their teepees set up near the Black Hills, in what is today called South Dakota. It was a careless tribe that did not honor traditional taboos. Because they constantly called the bear by name, it got so angry that it stormed down from the heavens, destroyed their settlement, and killed all of the people. Only one girl escaped his claws. She ran out into the prairie as fast as she could. But he chased her with great strides. He wanted to wipe her out, too. The seven brothers, the constellation Pleiades, heard her heartbreaking cries. They tried to obstruct the bear, but they could not.

The earth felt sorry for her, too. Mother Earth quickly let a glass mountain grow up right under her feet. It grew very high, and so the girl came out of the bear’s reach. The mighty bear tried to climb it, but it constantly slid down and its claws left deep crevices in the mountain. It did not give up though. Because it was a magical being, it painted its face with red mud and yelled at the Pleiades with its voice of thunder, “Toss the girl down to me or I will squeeze the mountain until you all fall down and I will eat all of you!”

Although the bear yelled this threat four times (four is a magical number, universally, for Native Americans), the seven brothers did not waver. The bear grabbed the mountain with its front paws and squeezed it with all of his might. The mountain became so small that it looked like a gigantic tree stump. The Pleiades were shocked and flew back up into heaven with the little girl. The bear chased them. When we look up into the night sky, we see the bear that is still chasing the Pleiades.

Anyone who doesn’t believe this story should travel to eastern Wyoming. There, Devil’s Tower, the core of an extinguished volcano, looms as a lonely pillar or huge “tree trunk” above the sagebrush prairie. The Cheyenne call this pillar Nakoeve, “the bear’s peak,” which the angry heavenly bear formed.4

Grizzly trying to climb Devil’s Tower

Artemis’s Children

For the peoples of the Mediterranean region, the image of the cosmic bear—which they saw as female—leisurely walking around the North Star was also familiar. The Greeks saw Ursa Major and Ursa Minor either as (1) the hands of the divine mother of the gods, Rhea, that are turning a spindle out of which come the threads of fate or (2) two bears that keep the heavy millwheel—its hub is the North Star—in motion for the goddess. The Hellenes also saw the nymph Phoenicia who was having a secret affair with Zeus. When his jealous wife, Hera, found out about it, lightning-bolt-slinging Zeus turned his lover into a bear and placed her in the stars. In the constellations of the big and small bears, the people of Crete saw the two bears that sheltered baby Zeus in their den and suckled him.

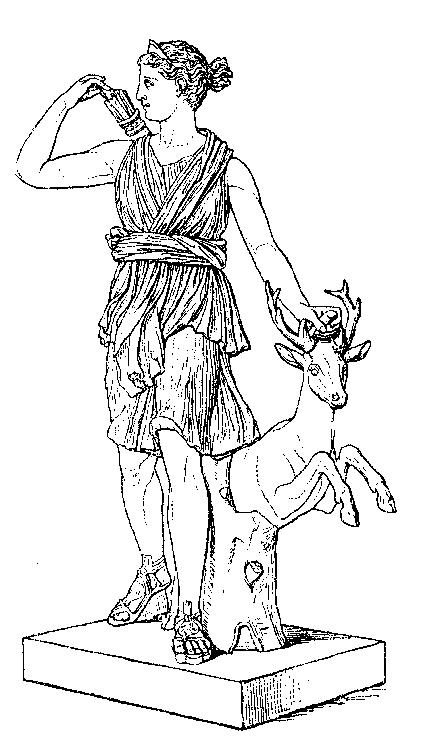

Each of these legends is from another epoch and another tribal mythology that over thousands of years grew to be the mythological treasure of antiquity. However, the most popular legend of this region regarding the bears in the northern sky comes from the cult of the wild female hunter, Artemis. Artemis, the “bear goddess,” who immigrated to Greece from the cold hyperborean forests of the north along with her brother, the sun god, was seen as the lady of all the wild animals. The beautiful, lithe hunter was untamable like the wild animals themselves. Her arrows brought quick death to forest and wild game desecrators. Only to childbearing women did she reveal herself as a gentle helper—as these conditions find themselves outside of conventional behavior patterns. In temples and groves dedicated to the goddess, often wearing a silver crescent moon as a crown, bears and other wild animals were free to roam.

In Athens and on the eastern coast of Attica, the festival of Artemis-Brauronia was celebrated as part of the midsummer festivities. Girls danced cult dances naked or in saffron-colored robes during the rite called arkteia. They were the virgins of Artemis and were called arktoi (bears). A ten-year-old and a fifteen-year-old girl played the roles of the big and little bears. They wore fur-like gowns the color of the Syrian bears that were at home in the forests of the Near East. Similar to the Cheyenne children’s game, the Brauronia “bears” lunged at the boys who came too near and pretended they would devour them.

Artemis was honored in the entire ancient world, but nowhere as much as in Arcadia in the mountainous, inaccessible Peloponnesus, the home of fauns, nymphs, and lustful Pan. The Greeks saw the “acorn-eating Arcadians” as bear people who were “older than the moon.” The temples of the aboriginal people were decorated with bear paws and skulls from bears that had been sacrificed, and the female priests wore bearskins. They were rumored to be, just as the Arcadian warriors were, very ferocious. The warriors wore bear’s heads with wide-open mouths on their helmets.

In these impassable, forested mountains, there once lived a girl named Kallisto who joined the wild band of virgins who honored the goddess and roamed the countryside. Just as her name indicates (Kallisto = the most beautiful), she was enchantingly lovely. This fact had not escaped Zeus, the father of the gods, and, driven by desire, he stalked her.

Artemis (Roman representation)

Kallisto’s father, Lycaon, the king of Arcadia, was a werewolf that delighted in feasting on human sacrifices. Zeus was so angry about the heinous crimes of Lycaon’s sons that he even sent a deluge because of them. But before it came to that, he was possessed by the desire to seize Lycaon’s beautiful daughter. However, the beautiful virgin had devoted her life to Artemisia and had sworn, like the goddess herself, to remain untouched. And so, wrapped in a bearskin, she roamed the mountains and forests with the other wild women and wild animals. She fended off all of lustful Zeus’s advances. But the father of the gods was a master of deception and could take on any shape he wished to. He had seized beautiful Europa in the guise of a wild bull, and he had even seduced Phokos’s daughter while disguised as a bear. This time he approached the innocent girl disguised as a female bear and was able to kidnap her and impregnate her.

The maiden kept a secret of what had happened and did not tell the goddess. But one day, as Artemis was bathing with the nymphs in a forest pool, Kallisto was hesitant to take off her cloak. When she did at last, her bulging belly revealed that she was expecting a child. The goddess was enraged, “Leave my circle of virgins immediately, you perjurer, and do not desecrate our water.” As punishment, she turned the girl into a bear, and the poor girl who still had a human heart and mind had to roam all alone as a shaggy, pregnant bear. Soon, she bore a strong son whom she named Arkas (the bear). Because his father was a god, he was a hero. He became the founder of the Arcadians, and the idyllic country praised by poets was named after him.

Very soon, fate separated small Arkas from his mother so that he could not remember her. The irony of fate also let him turn into a passionate bear hunter. One time, he encountered his mother in the dark forest. She recognized him and came up to him grumbling in a friendly way. But he did not recognize his mother who had given him his life. He only saw a wild animal and began to chase it mercilessly until they came to a sacred region of the Wolf’s Mountain where Zeus was worshiped as a wolf. Those whose shadow was seen in this sacred place were doomed to die and damned to go to the underworld into the realm of shadows. However, Zeus took pity on his lover and her son. He put Kallisto and Arkas up into the night sky in the most beautiful spot, as the big bear (Ursa Major) and the star Arcturus (in other versions as the small bear, Ursa Minor). Up there, the son is still stalking his mother, but he will never catch her.

However, Zeus’s jealous wife, Hera, did not grant the poor girl who had enjoyed her husband’s favor any pity. She arranged it so that Kallisto could never take a refreshing bath in Oceanus, the world stream that flows around the Earth and the seas; for that reason, the constellation of Ursa Major never dips below the horizon.

Bear hunter Arkas (Arcturus) in Booetes

The Once and Future King

All of the ancient indigenous peoples, the early hunters and gatherers of the northern hemisphere, saw a mighty bear circling the North Star in the night sky. In Neolithic times, when people became sedentary and started cultivating grains and building wagons, their imagery regarding the constellation changed. The Romans saw the seven main stars in Ursa Major as seven threshing oxen that unceasingly walk around the axis of the North Star. When they looked up into the night sky, the Germanics and Celts saw a huge wagon that slowly drives around the North Star. Three horses, or three oxen (the three stars of the shaft), pull the wagon. The small Tom Thumb, or rider, sits on the middle star of the shaft as a coachman (Fasching 1994, 102).

The pagan Swedes called this heavenly wagon “Thor’s Wagon.” But have we not just learned that Thor was also called “Bear”? Indirectly, the bear is still connected to this constellation for these peoples. These Swedes of long ago also believed that Thor sometimes came loudly clattering down close to the earth at midnight and that peace and fertility came in the wake of these nightly journeys.

In the early Middle Ages, this heavenly vehicle became hero king Dietrich of Berne’s hearse. When this Gothic king died, a wagon appeared and drove him up into the sky where he still sits in it circling the North Star. Christian zealots of the early missionary times tried to change this hearse to Elias’s or Paul’s coach of triumph, but it did not strike a chord with the only recently converted peoples.

In England and Scandinavia, Thor’s Wagon eventually turned into Charles’s Wagon (Charles Wain). This Charles is none other than mighty Charlemagne, and the wagon is his hearse in which he circles the North Star until his return. Like the Celtic King Arthur, Charlemagne is the great Rex quondam, rexque futurus, the once and future king, the archetypal universal king; he is not dead. He is only sleeping in the beyond, far removed. The beyond is in the stars, or, without it being a contradiction, deep in a mountain (such as for German King Friedrich Barbarossa and also Charlemagne) or on a faraway island (such as for King Arthur or Irish King Bran). It could also be a megalithic tomb, such as, for example, where the Bernese giant Botti rests. Botti sleeps in this grave and will only then awaken when the Bernese are in great need and call for him.

In these images of the faraway sovereign, we recognize the archaic legend of the bear king and his lover, the great goddess. Just like the king of the animals hibernates in the winter and returns in the spring, the human king withdraws until he rides down to earth again in a golden heavenly wagon, bringing a new time of happiness and justice. The Greeks called the Goths Amaxoluoi, “Men of the Wagon,” which may go back to the covered wagon, the vehicle in which this nomadic warrior people had arrived from the hyperborean north. But Amaxa is also occasionally used to describe the Big Dipper and Little Dipper. The Goths described themselves as descendants of a totemic bear. Fabled Berig (bear) is their ancestor, and their chieftains also called themselves Berige. The bear, the totem and coat of arms of the Goths, became the coat of arms of many cities that they conquered or founded, such as Bjorneborg, Hammerfest, Novgorod, or Madrid (Sède 1986, 63).