Chapter 14

Bear Saints and Devils

From there Elisha went up to Bethel. As he was walking along the road, some boys came out of the town and jeered at him. “Get out of here, baldy!” they said. “Get out of here, baldy!” He turned around, looked at them and called down a curse on them in the name of the Lord. Then two bears came out of the woods and mauled forty-two of the boys.

2 Kings 2:23–24

Around CE 590, Saint Columba took twelve companions and left Ireland and Wales for continental Europe (it is rumored he had to leave because he found the Irish women too beautiful, making it hard for him to keep his vows). In the name of Christ, these descendants of Celtic magicians walked through the realm of the Franks (more or less today’s France) with the front of their heads shaved in the Druid fashion and wearing white gowns; they were burdened with books and had bone relics of holy martyrs in bundles tied to their walking sticks. Steeled by severe asceticism, they advocated morals and good manners in the princely courts—so much so that these courts usually very much encouraged them to move on soon after the customary obligatory rights toward guests had been observed. As they roamed the countryside in southerly direction, they came to the Alemannic lands. Only the unswerving belief in their God and mission kept them from being afraid of the wilderness, wild animals, and evil pagans. The Alemannic tribes had berserkers into the seventh century.

When the holy men, fasting and praying, were walking along the banks of Lake Constance, they happened upon a loud, boisterous blót ritual, a festival in honor of Wotan and other pagan gods where beer flowed like water. The pious men were appalled at this devilish carrying on. Especially young Gailleach—known as Saint Gall—the son of an Irish king, was outraged. He turned over the beer vat, smashed the idols against a cliff, and threw the pieces into the lake. The fearlessness of the monks puzzled and impressed some of the pagans so that they let themselves be converted. Most of them reacted with hostility, however, and battered some of the monks to death.

The Messenger of the Age of Pisces

Saint Columba felt compelled to move on across the Alps, but Gailleach preferred Lake Constance—he loved to fish. Shamelessly naked Alemannic girls who occasionally happily splashed and bathed in the lake disturbed him; but he was able to drive them off with prayer and a ban.

As Columba was preparing to travel on, a temporary fever befell his friend Gailleach, who then stayed on the lakeside with his friend, Hiltibold. They were not afraid of the wolves, wild boars, and bears that populated the subalpine territory; after all, they were men of God and nothing had happened to the prophet Daniel in the lion’s den. They strayed through the wilderness for weeks until, weak from fasting, Gailleach fell near a waterfall on the Steinach River. When the bundle of sacred relics tied to the knob of his walking stick touched the earth, the monks saw this as a sign to stay at that place and build a monastery.

Gailleach went fishing to regain some strength by eating and got enough fish for the two of them. After they had eaten, a bear came roaming through and ate the leftovers. Gailleach crossed himself, talked to the bear in a brotherly way, and then commanded the bear to bring wood for the fire and logs to build the cloister. In the name of Christ, he asked the thick-skulled bear to drive the other wild animals off and then retreat into the mountain. As a token of thanks, he gave the vanquished bear consecrated bread and pulled a thorn out of its paw.

The bear that Saint Gall (Gailleach) subjugated also stands symbolically for the ancestral soul of the Alemannic peoples. The bear was the totem animal of the Alemannic warriors and was connected to the two main gods of the tribes, along with Woutis (Odin) and Donar (Thor). When the bear accepted the consecrated bread, it accepted communion with the spirit of the new Piscean Age that was coming into its time. Simultaneously, the bear gives the new spirit warmth, protection, and shelter by bringing wood for fire and building. In old representations, the bear comes from the left side, from the heart side. This indicates that the Alemannic soul had accepted the Christian message (Burri 1982, 86).

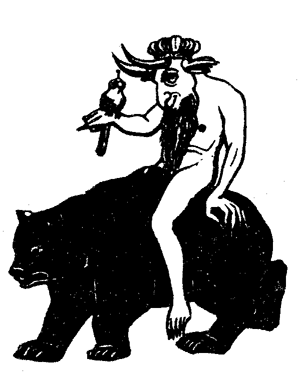

The Abbey of Saint Gall (Switzerland) developed out of the hermitage that was founded in this way—an incubator cell for the new Christian culture. The conversion of the wild Alemannic tribes pushed forward from here. An iconic design portrays this meeting, which depicts how Gailleach blesses a bear and gives it consecrated bread while the bear walks upright and gives him a log.

Saint Gall subjugates a bear (left: seal of the monastery library in St. Gallen, Switzerland).

Between the bear and Saint Gall in the illustration, a cross signifies their meeting and conciliation. The bears that help and protect him are not necessarily wild forest bears, however. It is more likely that they are genuine bearskins, dressed in bear furs and acting on the orders of their chieftain, Duke Kunzo, who told them to be hospitable to the stranger. Earlier, pagan chieftain Kunzo had called the monk, this unusual magician, to his daughter’s sickbed. Saint Gall was able to heal her with holy water and prayer, and from then on he stood under the Duke’s protection, of which he was much in need—he still had to fear the pagans’ revenge for insulting them and smashing their idols.

The festival of Saint Gall is held on October 16th, the time of year when the bears get tired and start to long for the quiet feeling of security in their earthen dens. By sending the bear away, Saint Gall also dismisses the old heathen heritage out of the realm of consciousness. It dwindles away from everyday consciousness and sinks into the cave of the unconscious. Some day—in the twilight time of a new age—this bear will emerge from the dark depths again. Maybe now, the beginning of the Age of Aquarius, the time has come?

The Bear as a Porter and Plowman

Not only Saint Gall but also other holy men and missionaries had to deal with the Germanic totem animal. Saint Mang, who legend says founded three cloisters in Allgaeu (in southern Germany) with Gailleach and Columba, also had to come to terms with bears. When he caught one nibbling on apples in the cloister garden, he successfully commanded it to stop and forced it to shake the tree so that the monks could gather up the fallen apples. Another bear scratched around on the root of an ancient pine tree and revealed a vein of iron ore. The discovery of the iron ore brought a financial boon to the cloister near Fuessen (where King Ludwig’s famous castle Neuschwanstein is) as well as to the surrounding area. Saint Mang rewarded the bear with consecrated bread and the promise that no harm would come to it. On another occasion, the holy man tamed a whole pack of bears and trained them to fight against the demon of Lechtal. He drove them like a pack of docile dogs to attack a lindworm that was terrorizing the area of Ronsberg (Germany). The united bears destroyed the dragon that had eaten many cattle and humans (Endroes and Weitnauer 1990, 526).

Other holy men were not impressed with the bear’s wildness either—for example, Saint Corbinian, missionary of Bavaria. When the devil appeared to him in the shape of a bear and slashed his packhorse, the man of God commanded the evildoer to carry the baggage in the horse’s place. And Saint Maximin was on a pilgrimage to Rome when a hungry bear also attacked his pack animal and devoured it. This bear also had to obey the holy man in the same manner. Not until it had carried his baggage to Rome and back to the German countries was it relieved of its compulsory labor.

Under the circumstances of the times, the “pilgrimage to the Holy See” seems to be a euphemism for a dangerous undertaking, and the inhabitants of the canton Valais in Switzerland tell a similar story to those of Saints Corbinian and Maximin: In the vicinity of the San Bernardino Pass, Saint Martin was attacked by a wild bear that clawed his pack mule. This bear, too, then bowed down to the spiritual superiority and carried the holy man’s baggage to Rome and back. The site of this event was named after the bear, Urseris (from Latin ursus = bear), and is today known as Osières. In another place, the tale is told of a severe bishop who made a bear plow for him after it had tore into his ox. And yet another similar tale tells of Saint Lucius who made a bear help him plow and carry firewood for a poor widow.

The story of the hermit Gerold, who turned his back on the sinful world and retreated into the Vorarlberg forest, shows a friendlier side to the erstwhile king of the forest. A bear that was being chased by a count and his dogs and nearly dead from exhaustion fled into the hermitage and laid his head subserviently into the hermit’s lap. The hermit blessed the animal and commanded the hounds to be quiet. Deeply moved by this miracle, the hunter jumped from his horse and took a knee in front of the holy man. He gave him the piece of land and the wood to build a cloister.

What is being expressed in these saints’ legends that are often almost interchangeably similar? Clearly, the new cloister culture was competing for the bear’s habitat because it was seen as pleasing to God to clear the dark forest and expand the area of cultivation where wheat and vineyards could grow. The legends also show the power of the new Christian moralism that was replacing the old natural, instinctive native way of life. The bear, which in this case represents the old heathen ways, learns to obey and do good deeds. Likewise, the heathen peoples are being wrested away from the devil and subjugated by the Church. It is highly probable that the bears in these stories are again not real bears but either heathen bearskins or feral people who had retreated into the forests. Besides incorrigible animists, the forest sheltered outcasts, escaped servants and vassals, and others who lived a bear-like and wild life in caves.1 They were seen as fair game, and the nobles sometimes made a sport of hunting them down and killing them like any other wild animals—bears, wolves, wild boars, and other game.

Saint Columba and Saint Gall with bears (L. Auers, Heiligenlegende, 1962)

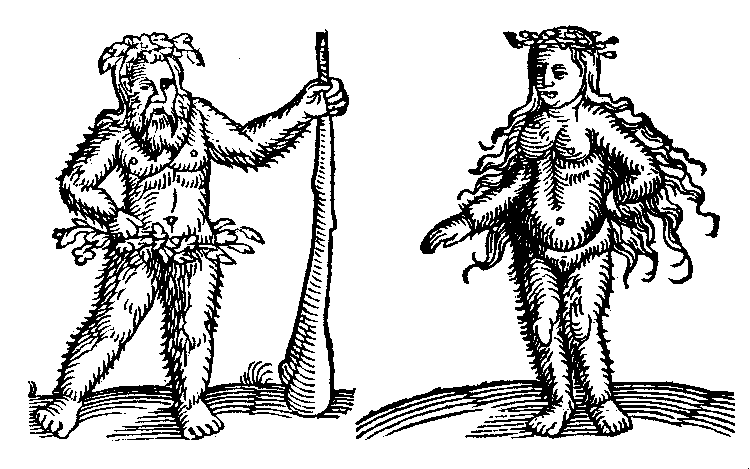

According to legend, wild people were naked or dressed in furs, had matted hair, and gathered or stole their food—fruit, roots, sheaves, and animals—at night. They loved music and dancing, carried clubs, and were shy but willing enough to be of service when captured. A subject of fascination all throughout the Middle Ages, they live on even today in carnival customs and costumes in Alpine countries in Europe. They were believed to have similar abilities as bears, such as being able to foresee the weather, find iron ore, and know the secrets of all the healing plants. But especially their alleged sexual instinct excited the imagination of the pious Christians. In the legend of Wolf-Dietrich of Berne, we hear about the wild woman who desired the knight:

When the master fell asleep, the wild woman came

To the fire and saw the prince’s body.

Walking on all fours, she looked like a bear;

Are you quite of this world, which devil brought you here?

Because the young knight rejected her she put a spell on him, so that he

had to stray through the woods for half a year and eat roots and herbs.

After Wolf-Dietrich gave in and slept with her, the story ended happily.

She accepted his faith and a miracle happened.

She was baptized, until then called Rough Ilse,

she was now called Siegesminne, the most beautiful far and wide.

Feral man and woman

The Bear Goddess in Nun’s Attire

Rather than become fully bedeviled and banned, many of the gods of the Mediterranean region simply changed their form. Suddenly, they appeared as saints and still populate Christian calendars as well as altars and niches in the walls of the churches. In this way, virginal Artemis, the bear goddess, made her way into the Christian era as a Christian virgin. She appeared as Columba the Virgin, who lived at the time of Christian persecution under emperor Aurelius. After her pursuers had put her in a dungeon because of her beliefs, coarse henchmen aimed to amuse themselves by raping her, but a bear that happened to live in the back of the dungeon defended her. She was later put to death as a martyr—tied up, slashed and torn with a hook, and beheaded—but, thanks to the bear, she had remained a virgin.

The cult of the goddess Artemis used to be celebrated in a bear’s den on the peninsula Akrotiri, on the island of Crete. The bear goddess transformed into “the sacred Virgin Mary of the Bear,” and her festival is held, significantly, on Candlemas Day. A bear-shaped dripstone that used to be the centerpiece of the heathen cult is now interpreted to be a bear that, upon disturbing Mary when she was drinking some water, was turned into stone.

The bear also appears in the legend of the arch martyr Thecla, an attractive maiden from a distinguished household who did not want to succumb to fleshly pleasures and refused to marry. So she dressed as a man, followed the apostle Paul, and was baptized by him. Her family was so upset with her that her own mother reported her to the governor who was a notorious Christian persecutor. She was arrested and thrown to the wild animals. When a bear was about to maul her, a lion, in answer to her prayer for aid, lunged and saved her. After then living to ninety-one years old despite much persecution and castigation, the saint left this world by entering a cave that closed behind her forever.

Killing a wild man (Pieter Brueghel the Elder, sixteenth century)

In the form of Saint Richardis we find another bear saint—this time, once again, in the Alemannic region. This daughter of an Alsatian prince was the wife of Emperor Charles the Fat. Accused of adultery, she took the test of fire and passed it. But afterward, she had had enough of the world and its ungodly doings and decided to devote her life to religious service in the name of the Lord. She retreated into the forest to live as a recluse, and there she met a bear that showed her a cave where she could set up a hermitage. A cloister was eventually built above this bear den at the foot of the Vosges Mountains in Alsace. Soon, it was discovered that the cave had healing power, especially for leg ailments. From the eleventh century onward, a bear was kept in the crypt and each pilgrim who came in the hope of being healed was required to give the bear trainer three coins (guldens) and a loaf of bread to the bear.

Forest Demons and Malicious Wild Animals

The Christians did away with animal worship; especially magical, sacred animals such as the bear, the wolf, and the raven were stripped of their divine nimbus. The bear, as the totem of warriors, ancestral spirits, bringer of fertility, and companion of the great goddess (by then degraded to a witch) now had to do compulsory service for the Church at the command of the saints (a similar punishment as given to the cheated devil). The bear had to haul heavy rocks to build churches and bridges, plow fields, gather wood, or even herd sheep, as for Saint Eutychius, for instance. However, the bear remained an ominous animal that possessed magical power. The more the animal was bedeviled, the more the fear of it grew.

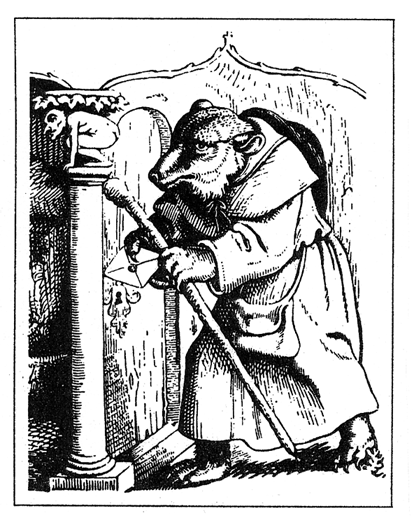

Bear in a monk’s cloak (unknown artist)

The same courtesies the bear bestowed on the Christian saints it had actually bestowed on magicians and shamans in earlier times. The bear was their companion and animal of power. In medieval times, the bear was believed to serve non-baptized beings by, for example, watching over the devil’s treasures or pulling the wagon for the mythological mountain spirit, Ruebezahl. People continued to only whisper its name because, just like the devil, the bear would come when called. People also believed that bears, like forest devils do, steal the colors from ferns and play other tricks.

The bear as a mount for a demon (from Jean Wier, Pseudomonarchia daemonum, sixteenth century)

The Church forbade contact with bears just like it forbade contact with evil spirits. The ecumenical council not only banned belief in astrology, interpretation of signs, reverence of nature, and other heathen practices but also the practices of keeping tame bears, wearing bear claws, and selling bear hair as medicine. The Quinisext Council decreed that former pagans who committed such crimes be sent to prison for six years. However, ninth-century artists were allowed to depict dancing bears.

Here and there, such as in Norway, for instance, farmers believed that bears protected their sheep, cattle, and goats from wolves. As a reward, they granted a bear one of the farm animals in the fall simply by turning a blind eye when a bear took one. In some communities in Allgaeu, Germany, farmers would put out the first calf born in the spring in the hopes that the bear would then leave the rest of the animals in peace on the summer pastures. But generally, people tried to avoid the bear, crossing themselves when they met the shaggy beast and reciting the traditional bear blessing from Saint Gall: “In nomini domini [in God’s name] my Jesu Christi, move on and retreat from our valley, you forest beast! Your territory is on the mountain and in the gorges. Leave us and our pasture animals in peace!”

An Alpine blessing, which is part of a larger blessing that used to be called out at night high up in the Alps for protection, goes like this:

Saint Peter, take your keys in the right hand.

Lock away the bear’s gait,

the wolf’s teeth,

the lynx’s claws,

the raven’s beak,

the dragon’s tail,

the vulture’s flight.

Protect us Lord from such dreadful hour,

that such animals bite or claw . . .”

One can see that the more these Christians tried to ban their own “sinful” animal nature, the more they began to fear wild animals in the forest. Bears became increasingly demonized as the incarnation of unruly powers. Saint Peter’s keys locked it away from the communities of good people. To meet up with the king of the animals was no longer awe-inspiring; instead, it only caused fear in humans and thus defensive reactions in bears. Nothing makes bears more aggressive than panicky people; or can they perhaps read thoughts as the Siberians and Native Americans claim?

Traveling artists with dancing bear (woodcut by Hans Weiditz, Augsburg, 1513)

Rigid medieval imagination divided the entire creation into good and evil, into creatures that were pleasing to God and those that had been ruined by Satan. Bruin found himself ever more on the wrong side in this kind of scheme. Believing they were doing deeds pleasing to God, people hunted down bears and wolves with almost fanatical determination—with poison, lances, crossbows, brutal traps, pitfalls, and nets. Accompanied by drums, trumpets, screeching women, and barking dogs, hundreds of hunters swarmed to drive out from their hiding places the “thrashing beasts” and “ferocious wild animals.” Bears were lured with honey, doused with brandy, and killed or taken into cruel captivity. (A liquor made from honey has its origin in eastern Prussia, in Germany, and is called Baerenfang, or bear trap.) It was not a rare sight to see a bear tied to a pole in the village square, eyes blinded, beaten until it had open wounds, and desperately trying to defend itself from the whipping and the dogs that were tormenting it. For the masses, the spectacle was less a gruesome form of entertainment than a moral edification. The bear incorporated sin and the devil, and the display showed how it had met up with its just fate.2

Animal researchers believe that bears actually did become more aggressive in the Middle Ages. The more often people intruded into their habitat so that they could not search for acorns, roots, and berries in peace, the more often they—driven by hunger—killed tame animals. Once the inhibition threshold has been crossed, a bear can turn into a habitual thief.

In the following tale about the mill bear, we can see how the once sacred animal had become a demonized being:

A spirit bear haunted a mill near Niederbronn in Alsace. The miller became desperate, fearing poverty and the ruin of his mill. No handworkers were willing to fix anything there and no apprentice stayed longer than one night. However, one day a perky young fellow showed up and offered his services. He had heard a bear spirit haunted the mill, but he was not afraid of it.

That night the wind was favorable, and the windmill blades turned at a good pace. The young man set to work. Toward midnight, he stretched out on some bags of flour to rest up. Just as he was about to nod off, a creaking could be heard. A black bear trotted in and sniffed the cases and bags. When it saw the apprentice, it lifted its paw.

But the apprentice was prepared. He had a freshly sharpened axe right next to him. He defended himself with the axe and cut off the paw of the attacker. The bear left the mill howling loudly.

Parading a captured bear in Valais, Switzerland (eighteenth century)

The master was happy to see the apprentice in good shape and content the next morning when he came in for breakfast. But there was no porridge—the miller’s wife was not there. They found her moaning and feverish in bed. And her lower arm was missing! She was exposed as a wicked witch and arrested.

Who is this black witch who appears as a bear? Knowers of mythology will recognize the grain goddess, the grain mother, who appeared in pagan times as a bear or accompanied by a bear. Now, having been banned from consciousness, she has become an evil nocturnal spook—so it happens to all gods and goddesses who are no longer honored and are pushed into the unconscious. They become black demons of the night.

Brother Klaus’s Bear of Light

The visions of Swiss saint Nicolaus von Fluee show a pleasant picture by comparison. Brother Klaus was a poor mountain peasant but had shown himself to be a courageous warrior and councilman. One day—it happened to be October 16th, the patron day of Saint Gall—he left his wife and ten children and retreated into the forest as a hermit. It is said that he lived for twenty years from nothing but the sacrament, from bread and wine. Princes and rulers made pilgrimages to his hermitage to ask him for advice, and, thanks to his clear spirit, he was even able to hinder a civil war in Switzerland. He also had interesting dreams and visions while he was living in his hermitage.

Nicolas von Fluee, 1417–1487

In one of his visions that shook him to the core, a magnificent wayfarer appeared to him. He had a wide-brimmed hat, a walking stick, and a large cloak. The wayfarer began to sing and it seemed like the entire creation sang along. The Pilatus Mountain (near Lucerne, Switzerland) sank down to the level of the earth and the blessed ones—the dead—appeared. In the midst of this overwhelming scene, the clothes of the wayfarer changed, and suddenly he stood in front of the monk dressed in bear’s fur. The fur was sprinkled with a radiant gold color. Brother Klaus felt that the stranger had communicated to him the mysteries of heaven and earth.

It was surely “Woutis” (Wotan), the god of his Alemannic ancestors, who had entered his subconscious and taken shape in his vision. (Wotan, the wayfarer, is known to appear with a wide-brimmed hat, staff or spear, and a wide cloak). Brother Klaus had been able to recognize this old god and not see him as a devil—as was usually the case in the Middle Ages; he had united the vision with his steadfast Christian faith and had seen the radiant divine bear, the chieftain of the dead spirits that lived in the mountain (Burri 1982, 97).

In another vision, three noble-looking men appeared to him. They asked him whether he would put himself with body and soul into their hands. The hermit answered, “I will not give myself to anyone but almighty God.” After hearing this, the three men laughed merrily and prophesied that goodly God would free him of his earthly burden in his seventieth year of life, and then they gave him “a bear claw and the banner of the mighty army.”

Who may the three men have been? They were probably the ancestral gods, Wotan, Donar, and Tyr. They could laugh merrily with this saint because he did not ban them back into darkness. His Christianity was not exclusive, narrow, and dogmatic. So they blessed him with the power of the bear, as well as his ancestors, the Alemannic warriors. In this way, Brother Klaus helped the Alemannic soul reconcile with the inflexible beliefs that the Irish-Scottish monks had brought to his country.