Chapter 15

Bear Plants, Bear Medicine

In the forest a leaf falls from a tree:

The eagle can see it,

the coyote can hear it,

but the bear can smell the falling leaf.

Native American proverb

When spring thunderstorms clash and the godly bear, Thor, smashes the bones of the cantankerous ice giants with his lightning hammer until their icy stronghold turns into thaw water, it is time for the terrestrial bear to leave its paradise of sweet dreams and come out of its den. After the long winter, Bruin does not look as mighty as usual. The bear has lost a lot of weight—about one third of its normal bulk—and its fur looks like a worn-out coat dangling around its bones. During the long winter sleep, the bear does not urinate or defecate. It has a terrible thirst—it is as thirsty as a bear!—so the first thing it does is quench it. Then it begins to eat purgative herbs, mainly looking for spicy hellebore, a strongly purgative and circulation-accelerating plant. The natural plug of excrement that has closed off the lower intestine over the winter is excreted, and then the proverbial hunger—“hungry as a bear”—comes into play.

Brooklime, watercress, wild onions, chickweed, young nettles, sour dock, and many other edible spring plants that make up the bear’s first meals and reactivate its metabolism and circulation also fire up its glands and inhibit anaerobic fermentation and putrefactive agents in the intestines. They are the same herbs that our ancestors ate as blood-cleansing cures—usually also in the spring after a long winter without fresh greens.

Willow bark, willow buds, and meadowsweet shoots (Filipendula) that contain natural aspirin (salicylic acid) flush excess uric acid out of blood and tissue (for bears as well as for humans) and free the bear of the back pain that usually comes from lying for so long in the cold. Bears like to eat the young shoots of hogweed as much as traditional European farmers will make a soup of them as a stimulating and digestive spring meal. Bears also like young dandelions, a traditional addition to a spring salad that humans also enjoy. Dandelion increases gall secretion, is diuretic, clears out slag, and tones the intestines. Bears clear winter catarrh and phlegm out of their lungs by eating plantain and colt’s foot leaves. As one can see, in the bear’s apothecary we find the Celtic-Germanic “nine herbs” that people also traditionally ate during spring festivals and are still occasionally found in cleansing Maundy Thursday or Good Friday soups.1

Plants That Induce Sleep

Just as Bruin looks for fresh greens in the spring, he also finds sleep-inducing herbs in the fall that help him go into hibernation. Humans of olden times, as well as early scholars, were certain that Bruin knew these plants very well. A Swiss legend tells of a cattle herder in the high Alps who saw a bear greedily eating a certain herb. It made him curious, and he tasted the plant himself. His eyelids became so heavy that he lay down under the upside-down cheese vat to take a nap. When he woke up, it was spring; he had slept soundly over the winter despite bitter cold.

Another story tells about a poor, old widow who lived alone in a drafty cottage on the edge of the forest. She was weak, and it was hard for her to gather enough wood for the winter. One day, when she was gathering brushwood, she noticed a bear in a meadow. She observed how the bear carefully dug up a creeping plant and ate it while grumbling happily. Afterward, the bear did some somersaults and then trotted off happily on its way.

The old woman was curious and tried some leaves of the plant, too. On the way back home, she got so tired that it was all she could do to make it to her bed of straw before falling asleep. In her dreams, she floated up into heavenly realms with blossoming meadows where happy people were dancing in rounds and singing songs. She also saw a beautiful woman with billowing hair and big pearly white teeth and thought it must be the goddess herself. At the feet of the goddess, the same bear lay that she had seen earlier in the forest. He let her pet his furry coat and grunted happily as if he were licking honey. When the old woman awoke, she thought she was still dreaming because a mild spring wind blew through the window and outside in the greening trees she heard spring birds singing. Though it seemed to her she had only slept for a few hours, she had actually slept the whole winter and the frost giants were long gone into the high glacial mountains. When she saw her reflection in the water, she was shocked. In the reflection, she saw a young woman with rosy cheeks and full hair without any gray streaks looking back at her. The “sleeping plant” had rejuvenated her.

A Master of Botany

When the famous American grizzly bear researcher and wilderness expert Ernest Thompson Seton wrote that the bear knows more about plants and roots than a whole college of botanists, he was not telling us anything new. The bear’s incredible herbal knowledge has impressed many observers. But what else could one expect of the wise king of the forest? A bear’s nose is at least as good as that of a bloodhound. Researchers debate about how many hundred times better a bear’s nose can smell than a human’s modest olfactory organ. A bear can already smell from a great distance very exact nuances regarding what it can eat and what it cannot eat. For this reason, especially old bears with a lot of life experience can hardly be fooled by poisoned bait.

Even in antiquity, the bear was considered the doctor among the animals. For the hunting peoples of olden times, it was always the bear spirit that showed the healers which healing plants to use for lack of appetite, for fertility, or to drive off bad spirits in general. It is not by chance that an old Celtic coin shows a bear with a root in its mouth. For the Native Americans across the board, medicine is not medication like we understand it to be. A medicine being—whether a healing plant, peace pipe, medicine man, medicine woman, or medicine animal—is a being with power, a being with mana, that can be tapped into under certain circumstances. Hardly another among the animals has as much “medicine” (mana) as a bear does. Accordingly, the strongest healing plants, especially roots, were known as “bear medicine.” The Midewiwin, the grand medicine society of the Ojibwa, carved the strongest healing roots to look like bear claws and wore them as a necklace, just like a genuine bear claw necklace.

So that medical plants do not lose their power, they are not to be dug out with metal tools but with wooden or horn tools, or even like a bear itself would do—with bear claws. Such rules for gathering herbs are universal amid native peoples and can be traced back to the Stone Age—that is, to the time before metal was ever used. According to medicine man Bill Tallbull, bear medicine is so strong that it should not be kept in the house or even in the cab of a pickup truck as one could be overwhelmed by it.

The “doctors” of the Californian Native Americans often wore bearskins or mountain lion skins and lived, similar to the berserkers, away from the rest of the tribe in the wilderness. They were considered so full of power that they could not be tolerated in the villages; their power could be dangerous for normal people. Their medicine had the power to heal but also to kill. One would find bear claw tracks on whomever had been their victim.

Native American bear images from the northwestern coast. Left: Tsimshian; right: Kwakiutl.

Among the Iroquois, the bear mask society followed the instructions of the bear spirit and had the shamanic medicine power (orenda) to heal gout and rheumatic ailments. Long ago, the bear spirit had appeared to a half-starved hunter who was lost in the forest. Out of pity, the bear gave the suffering human medicine songs and taught him dance steps. With these, humans could conquer the plagues brought on by the cold, moist weather.

The Celtic, Germanic, and Slavic ancestors of the northern Europeans also knew about potent bear plants. Contrary to wolf plants like baneberry, daphne, stinking hellebore, or spurges that are caustic or highly poisonous, or useless, foul-smelling “dog” plants, they saw bear plants as motherly, protective, and refreshing. They called especially big and vital plants “bear plants,” such as hogweed, burdock, angelica, or lovage. They saw a bear character in such tough plants as bearbind. Plants with especially strong magic—for instance, club moss, bear’s garlic, burdock, and maidenhair moss, or bear’s bed—were known to drive off witches, demons, and nightmares, just as bear teeth, claws, and hair do. Bear’s bed is also known in German as Widerton, meaning “opposing magic,” because, usually worn in the hair or on a hat, it was used to counter black magic.

Bear and elk with fly agaric (Siberian drawing, author unknown)

Plants that encourage hair and beard growth, such as stinging nettle, burdock, or Alsatian broomrape, were also categorized as bear plants. Furthermore, the plants that make milk rich and sweet (in animals and in humans), increase potency, and strengthen or protect the uterus were seen as bear plants provided they were not put directly under the protection of the great vegetation goddess herself, Freya or Mother Holle, or later on under the Virgin Mary. And finally, also classified as veritable bear plants were the consciousness-altering, magical plants that allowed the berserkers to get to know their own animal nature.

Bear’s Garlic, Bear Leek, or Ramsons

Blossoming bear’s garlic

Anyone who has been in the Alps in the spring has noticed how bear’s garlic (Allium ursinum) still has the status of a somewhat sacred plant. In the spring, no mountain farmer would go without blood-cleansing bear’s garlic soup (made of the leaves before the plant flowers) even though in modern times the winters are not like they used to be as far as a lack of vitamins go. Just like the bear’s appearance drives old man winter away from the countryside, this delicate green soup drives winter weariness—scurvy, scrofula, iron-deficient anemia—out of the limbs and entire body. The sulfuric mustard oils of this plant that is related to the onion clean out the stomach and intestines, regenerate intestinal flora, release tension, and give a warm, fuzzy feeling like that of a bear hug.2 It is said one should eat bear’s garlic on Walpurgis Eve (April 31st) to avoid harm from the witches who fly around especially throughout that night.

Otherwise quite sober-natured herbal pastor Johann Kuenzle could not help but grow effusive when he wrote about bear’s garlic: “People who are chronically sick,” he writes, “people with eczema, rashes, scrofula and anemia should revere bear’s garlic like gold. . . . Young people will blossom like a rose arbor and open up like pinecones in the sun,” and “people who are full of rashes and eczema, their whole bodies scrofulitic, as pale as if they had already been lying in their graves and the chickens had scratched them back out, will look completely refreshed and healthy after a good, long cure of this goodly gift from God” (Kuenzle, 1977, 30). Bears also enjoy this liliaceous plant, which smells like garlic, as a purifying cure in the spring. Kuenzle proclaims “our ancestors learned about this plant by observing bears” (Kuenzle 1977, 31).

Clubmoss

Common clubmoss

Common clubmoss (Lycopodium clavatum) is even more “beary” than bear’s garlic. In ancient times, it was believed that this dark green forest floor plant had the same kind of magical power as a bear’s paw. Indeed, the word “lapp” on the end of the German word for the plant (Baerlapp) goes back to a Celtic word meaning “paw.” The plant sprouts really do look like shaggy animal paws. The botanical name Lycopodium means “wolf’s paw.”

Other names of clubmoss are stag’s-horn clubmoss, wolf-paw clubmoss, foxtail clubmoss, running clubmoss, running ground-pine, running pine, running moss, and princess pine. In German, it is also called devil’s claw (Teufelsklaue), witches moss (Hexenmoos), and Drude plant (Drudenkraut). The last one most likely refers to Druids because, for Celtic magicians, the plant was shrouded in legend. A sacred plant for them—they called it selago—they were very careful about how they picked it. Barefoot and robed in unstitched white gowns, they sought the plant in new moon nights. After a long incantation, they picked the twigs with the left hand. No iron could touch the plant because it would drive away its spirit. They offered the plant mead (honey wine) and bread in reconciliation and used it for amulets to protect from all kinds of harm, from “the evil eye,” bad magic, and bewitchment.

Even today clubmoss still has a reputation. An old neighbor of mine would stick a twig on his hatband on occasion, claiming it would help him when having to deal with officials and higher authorities. Young girls who want to get married used to be advised to sew some clubmoss onto their dresses so that they would be irresistible. The sick were advised to put some of it in the Saint John’s belt (a garland of various plants woven and worn as a garland or around the waist at midsummer) and toss it into the Saint John’s fire (the traditional midsummer fire) so that all their suffering would burn there. To a certain degree, some of these customs even still live on in rural areas in Europe.

The yellow pollen of the spores are called lycopodium powder (German Hexenmehl = witch’s flour, Blitzpulver = lightening powder, Erdschwefel = earth sulfur, Drudenmehl = Drude [Druid] powder). When these oil-emulsifying and aluminum-containing spores are tossed into an open fire, lycopodium powder sizzles and pops as if Asbjørn (the godly bear) himself were striking with his mighty paws. Stone Age shamans used this dramatic light-explosive effect as did theater directors in past centuries. The powder was also used as the flash in early photography.

Just as the Europeans of long ago did, wherever it grew, Native Americans also used the spores as wound powder that absorbed moisture and accelerated healing. It was sprinkled on the navel of newborn babies to accelerate healing and used as powder for baby bottoms. Pastor Kuenzle prescribed the plant, or baths of the cooked plant, for cramps and varicose veins; he also recommended the plant cooked in wine and taken as a cure for gall and bladder stones. Maria Treben, who brought the natural “God’s Pharmacy” (herbal healing) back to modern people, recommends it for cirrhosis, cramps, high blood pressure, shortness of breath, and other ailments (Treben 1982, 9).3

Bearberry

Bearberry

Anyone who has suffered from a painful bladder or kidney infection and been lucky enough to cure it with bearberry tea (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi) has learned to appreciate the healing power of this plant. A decoction of the leaves disinfects the urine. However, one should avoid eating meat when taking bearberry tea because its effect is dependent upon an alkaline reaction in the urine.

Bearberry is a creeping dwarf shrub from the heather family that is part of the bear biotope from Europe to Siberia and North America. It is guaranteed that no hungry bear will amble past these berries with indifference in the fall. Wherever it grows, for the Native Americans bearberry is one of the most important “medicine plants” (powerful plants). The berries were threaded for necklaces or roasted in bear fat or fish oil in a pan where they puff up and pop like popcorn (Moermann 1999, 88). But mainly the leathery leaves were added to a mixture of tobacco, staghorn sumac leaves, and the inside bark of common dogwood. This mixture was known as kinnikinnik (Algonquian = smoke mixture). According to Bill Tallbull, this smoke attracts the spirits and makes it possible to contact talking coyotes, thunderbirds, and the bear spirit, as well as distant chiefs of other tribes.

Burdock

Another bear plant worth mentioning is burdock. Burdock radiates a bear-like vitality with its huge, elephant ear–like leaves, mighty taproot, and a flower head with many scratchy hooks (miniature bear claws). The botanical name Arctium lappa, means, “bear paw” (Greek arktos = bear; Celtic lapp = paw). As a genuine bear plant, it also promotes hair growth. In apothecaries in Europe, one may still find burdock hair oil made from the roots or seeds. One can make the hair oil by macerating the crushed root in oil for three weeks in a warm place. The oil is also used to treat rheumatism and joint and skin ailments.

The Germanic tribes dedicated this composite to mighty Thor, the godly bear, whose lighting strikes could drive off dragons and other creepy, crawly creatures. It follows that Germanic folk medicine had a tea made of the roots for any “worms” that can nestle into the body and rob people of their strength. The tea does indeed stimulate liver and gall bladder functions, is sudorific, and flushes toxins out of tissue and organs. The root also has bacteriostatic and fungicidal attributes and can be used externally for acne and infected wounds. Burdock is definitely a bear of a plant. It is even claimed that the plant can be used to counter bad magic: Burdocks in the hair keep the devil away; burdocks in cows’ tails keep away witches who like to sneak up and drink the milk; and a burdock leaf under the sole of her shoes was believed to help a woman with a prolapsed uterus.

Bear’s Milk, Licorice, and Hogweed

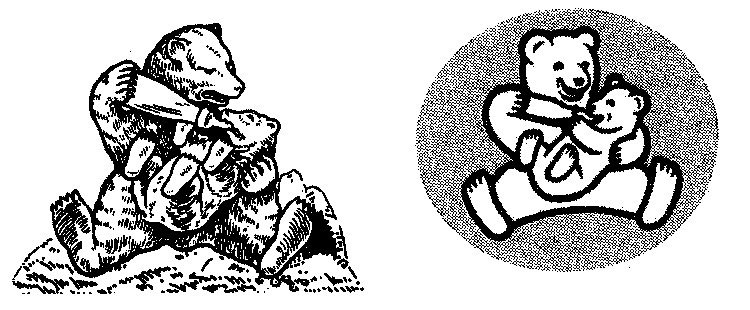

As has already been mentioned, a bear’s milk is very rich (30 percent fat) and very sweet. Legends tell that anyone who drinks bear’s milk will become a hero. A Russian tale tells of one such hero who had to get milk from a forest bear to heal his ailing sister.

“Bear’s milk makes us strong!”—the slogan of the Bernese Alpine milk producers. Left: original print; right: present version.

Understandably, Alpine meadow flowers that give cows’ milk an especially aromatic flavor are also connected to bears. One of these milk herbs is bear wort (Meum athamanticum), which is also called baldmoney or spignel. The signature of this aromatic umbelliferous herb is very distinct: It has a thick brown bunch of “hair” on the rootstock that looks similar to bear fur. Wherever this native of northern Europe grows, it is a highly respected plant in folk medicine. It is known to strengthen the stomach and heart and is usually taken in the form of schnapps (it can be macerated in clear alcohol, such as vodka, for a couple of weeks).

Alpine lovage, or mountain lovage (Ligusticum mutellina), is equally cherished as a milk herb. An Alpine saying goes:

Panicle, mountain lovage and Alpine plantain are the best things our little cow did eat.

According to legend, long ago a lazy, disrespectful female Alpine herder cursed mountain lovage because the cows had so much milk from eating it that she was forced to milk three times a day, and it was very hard work to get the cheese wheels down the mountain. The curse went into effect, and the milk-giving power of the plant receded. The prayers of an old man canceled the curse—but only to a degree.

Native Americans recognize a warrior plant with bear power in osha (from osa in Spanish, meaning “female bear”), also known as bear medicine or wild lovage, which grows in the southern Rocky Mountains. Regarded as a cure-all, the warming, sudorific root is chewed for flu, viral diseases, and stomach and intestinal ailments; women use it to activate menstruation; and the dry root is used for incensing to purify the atmosphere. The Crow mix it with kinnikinnik. Warriors chewed on the root when they had to run long distances because it had a good effect on the lungs, and an amulet made of osha helps protect from rattlesnake bites. When asked about the plant by anthropologist (animal behaviorist) Shawn Sigstead, the Navajos he was interviewing claimed, “We learned about the healing power of this plant from the bear.” The skeptical Harvard scholar, however, wanted to find out for himself if bears were really interested in the plant. When he tossed the plant into a bear cage, the bears pounced on it like cats do on catnip or valerian and chewed it with obvious delight, spread the chewed-up plant matter onto their paws, and then rubbed it onto sores and areas where they had fungus. Follow-up research done with grizzlies in Alaska showed that they reacted just as “crazily” when they happened upon the plant. In the wild, they ate it as a means against intestinal parasites, chewed the root, and washed wounds with it or even washed their faces with it. A male bear in love will also dig it out and bring it to the female bear he is wooing (Storl 2001, 203).

Wild licorice (Astragalus glycyrrhiza), closely related to licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra), is another bear plant that grows in sparse forests or as a cover after clear cutting. In the Middle Ages, the juice from the root was cooked into a syrup and made into a medicament with some honey, blood, various herbs, and a good amount of opium. It was then used to remedy poisoning, wild animal bites, and the pestilence. For Native Americans, licorice was also considered a strong bear medicine. Indigenous prairie tribes chewed on the root while in the sweat lodge because it helped them withstand the last nearly unbearable rounds of heat while sweating. For them, the sweating that drives out impurities of the body and soul serves as a preparation for contacting mighty spiritual entities.

Hogweed

A common plant called hogweed (Heracleum sphondylium) dominates over all the other plants and grasses in the meadows with its mighty, juicy stems and big, lobed, hairy leaves. The bear nature of this giant becomes evident with the seeds’ aphrodisiacal effect. After all, the bear was known since earliest times as a veritable fertility beast. Hogweed should not be confused with giant hogweed, or giant cow parsnip (Heracleum mantegazzianum), from the Caucasus, which has recently become an invasive plant in Europe and North America and should be avoided as much as an angry grizzly bear. Just to touch the plant—especially when the sun is shining—will cause an inflammation with a blister as big as a hot iron would leave.4