In 1857, a year after her marriage, Eva became pregnant and the couple moved from a country estate to Berdichev, one hundred miles southwest of Kiev, to be near her mother. Seven years earlier, in March 1850, Honoré de Balzac had traveled through the countryside, “sandy tracts studded with clumps of pines,” and had married Evelina Hanska in the Polish Roman Catholic church of Santa Barbara in Berdichev. In Conrad’s fictional fragment, “The Sisters,” the Ukrainian hero remembers scattered white huts with high thatched roofs and uneven windows, and the green cupola of a village church, topped by a gleaming cross. In “Prince Roman” Conrad also recalls his native landscape and portrays the great hedged fields, the dammed streams that made a chain of lakes set in the green meadows, the cold brilliant sun “above an undulating horizon of great folds of snow,” the hidden villages of peasants and the region where wolves were to be found.

Berdichev, like nearby Zhitomir, where Conrad also lived as a young child, was typical of many towns in the Polish Ukraine. It had been fortified against invasions in the sixteenth century, but was later destroyed by Tartars and Cossacks. In 1630 a Polish Carmelite monastery was built and in 1739 a Roman Catholic church. The town prospered by supplying flour to Napoleon’s troops during the invasion of 1812, became a major grain and cattle market, and began to manufacture shoes and clothing. Berdichev also became a place of pilgrimage and a center for publishing, though these were suppressed by the Russian government in 1866.

When Apollo and Eva married, Berdichev, the fourth-largest city in the Ukraine, was the second-largest Jewish community in Russia. Ever since 1790, when Jews had been allowed to open shops, the Jews represented eighty to ninety percent of the total population. It had a Jewish hospital and three Jewish schools, and was a major Hasidic center, founded by the charismatic eighteenth-century leader, Rabbi Isaac ben Levi.1 Sholom Aleichem portrayed the town in Gants Berdichev (1908). Conrad, who grew up among persecuted and patriotic Jews, was, for his time and place, astonishingly free of anti-Semitic prejudice. For historical, familial and personal reasons, he was essentially sympathetic to the Jews, and portrayed Hirsch in Nostromo and Yankel in “Prince Roman” quite favorably.

Jozef Teodor Konrad Nalecz Korzeniowski was born in Berdichev on December 3, 1857. Jozef was the name of his maternal grandfather, Teodor of his paternal grandfather and Nalecz was the szlachta name. Konrad, which he later anglicized and adopted as his surname, was the name of two of Adam Mickiewicz’s creations: Konrad Wallenrod, the eponymous hero of that patriotic poem, and Konrad, the main character of Forefather’s Eve. To a Pole, the name symbolized an anti-Russian fighter.

Conrad was born one year after the end of the Crimean War, when Russia’s defeat by Britain, France and Turkey had once again raised hopes of Polish independence. Apollo celebrated his son’s christening with a characteristically patriotic-religious poem, “To my son born in the 85th year of Muscovite oppression.” It alluded to the partition of 1772, burdened the new-born child with overwhelming obligations and urged him to sacrifice himself (as Apollo would do) for the good of his country:

Bless you, my little son:

Be a Pole! Though foes

May spread before you

A web of happiness

Renounce it all: love your poverty. . . .

Baby, son, tell yourself

You are without land, without love,

Without country, without people,

While Poland—your Mother is in her grave.

For only your Mother is dead—and yet

She is your faith, your palm of martyrdom. . . .

This thought will make your courage grow,

Give Her and yourself immortality.

Andrzej Busza explains that Apollo’s commitment to Polish patriotism, and scorn for those who rejected it, was absolute: “Conrad had been brought up in an intensely patriotic atmosphere; amongst people who constantly thought in such categories as the national cause, duty to one’s country, sacrifice for the nation; and, on the other hand, such [reprehensible] notions as the lack of patriotism, the neglect of patriotic duties, and, above all, betrayal.” There were four possible attitudes toward Russian rule in Poland: loyalism, conciliation, resistance and emigration. Uncle Tadeusz chose the second, Apollo the third and Conrad the fourth. Conrad’s refusal to follow his father’s exhortation and example, and his voluntary exile from Poland in 1874, were a source of lifelong guilt.

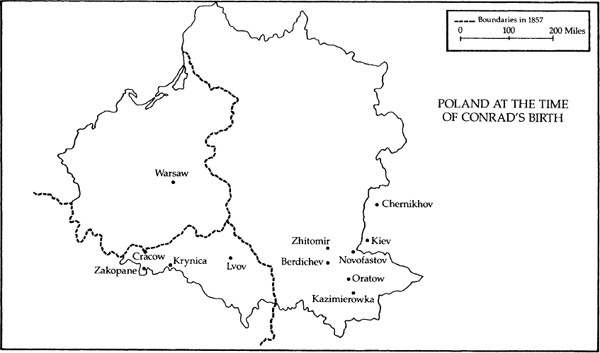

Conrad moved almost as frequently during his Polish childhood as he did during his years at sea, and he formed no close friendships in Poland. He lived in Berdichev, Zhitomir, Warsaw, Vologda, Chernikhov, Novofastov, Kiev, Lvov, Cracow and Krynica, and took holidays abroad in Odessa, Switzerland, Austria, Germany and Italy. At the beginning of 1859 the family moved thirty miles north to Zhitomir, where Apollo wrote, translated and worked in a short-lived publishing company. Conrad’s first childhood recollection was of a scene that occurred early in 1861, just before the family’s happiness was shattered forever. It concerned his mother and music; and was associated with a precious experience, a dramatic entrance and a benison of maternal love that focused exclusively on himself: “my earliest memory is of my mother at the piano; of being let into a room which to this day seems to me the very largest room which I was ever in, of the music suddenly stopping, and my mother, with her hands on the keyboard, turning her head to look at me.”2

Apollo belonged to the revolutionary generation of Mazzini, Garibaldi, Herzen and Kossuth. But as the failed plotter of a failed insurrection, living amidst violence and catastrophe, he had to survive on his memories and his dreams. Roman Dmowski, a late-nineteenth-century right-wing nationalist, condemned the self-destructive legacy of Polish Romanticism, exemplified by Apollo, which built “political prospects on purely illusory grounds . . . [and embarked] on political activity with no specific aim in view and with no prior estimation of the means at disposal.” Nevertheless, if the choice were between passive acceptance and reckless action, Apollo would certainly choose to act.

A. P. Coleman states that after the death of Czar Nicholas I in 1855, Apollo became the prime mover behind a secret society called The Trinity, which opposed conciliation and urged active resistance to Russian oppression: “At first its objective was purely spiritual: to nourish resistance to the idea then insinuating itself into the class from which most of the [university] students came, that national emancipation could be achieved through political cooperation with Russia or with the Tsar. Its purpose was thus to keep alive the flame of Polish nationality and the conviction that, though the Powers considered Poland as dead, enough energy to save the nation still survived.”3

In Warsaw, in the autumn of 1861, Apollo helped found a newspaper and the clandestine Committee of Action of the Red organization, which had developed from several conspiratorial groups. His extreme views were not generally accepted and he narrowly escaped death at the hands of a terrorist group, the Stilettists. Conrad later objected to a critic (probably the left-wing Edward Garnett) calling him “the son of a Revolutionist” and unconvincingly insisted that “No epithet could be more inapplicable to a man with such a strong sense of responsibility in the region of ideas and action.” But Apollo, one of the most radical Red conspirators, clearly advocated violent revolt and national insurrection.

When the elections to the town and rural councils began in Warsaw on September 23, 1861, Apollo urged the electorate not to cast their votes. His leaflet “The Mandate of the People” “insisted that the electoral law was an attack on Polish national unity, both in the sense that the franchise was too narrow and that Lithuania and Russian Ruthenia [the Ukraine] were denied constitutional freedoms.” Despite his extremely precarious position, Apollo was reckless about his own safety, and deliberately provoked the authorities by his outlandish dress and his public pronouncements: “ ‘An honourable but too ardent patriot, [he] went about Warsaw dressed in peasant fashion, in a peasant smock, frightful cap and knee-boots, attracting universal attention and exerting quite an influence on the youths gathered around him, by his intelligence, education, talent as a writer, and by his eloquence.’ ”4

Apollo paid dearly for his rash courage. Shortly after midnight on October 20, 1861, while he was writing and Eva reading in their flat on Nowy Swiat, a main street in the center of Warsaw, the doorbell suddenly rang. Apollo was arrested by the Russian police and was taken away in a matter of minutes. He spent seven months locked up in the Warsaw Citadel, suffering from rheumatism and scurvy, and waiting for the charges to be drawn up against him.

Under the “wide-browed, silent, protecting presence” of his mother, who was dressed in the black of national mourning in defiance of ferocious police regulations, the three-year-old Conrad remembered standing in the large prison courtyard and looking at his father’s face staring at them through a barred window. Though Apollo’s conspiratorial comrades offered to help him escape, he refused to consider this—ostensibly because he did not want them to risk their lives for his sake, but also because he wanted and welcomed this martyrdom for Poland.

Heightening the drama of his trial, Apollo later wrote that the Russian authorities were well aware that he “was not only a participant in but [also] the principal leader of the entire rebellious movement and the demonstrations designed to overthrow the government of our most gracious tzar.” In fact, he was merely suspected of complicity in plotting the rebellion. If anything had been proved against him, he would either have been shot or sentenced to Siberia, where death would have been almost certain.

Since Apollo pleaded not guilty and no witnesses could be found to testify against him, the Russians, suspecting he was guilty, accused him of less serious charges: 1. that he had formed a committee which opposed elections to the Warsaw City Council, 2. that he had been the chief instigator of brawls in a confectionery shop, 3. that he had advocated an illegal union between Lithuania and Poland (a union had existed from 1569 to 1795), 4. that he had organized communal prayers for political martyrs. The court stated that “indirect evidence of his activities and of his alien way of thinking was found in the letters from his wife,” foolishly written before she had joined him in Warsaw, which warned “him against returning to [Zhitomir] where he may be arrested.”

Though Zdzislaw Najder speaks of Eva’s “unshakable decision to participate in all his activities,”5 she was actually forced into exile. Her letters had incriminated Apollo, and on May 9, 1862, she was convicted with him. Both were sentenced to indefinite exile in (as Apollo requested) the town of Perm. Sixteen years after leaving St. Petersburg, he was forced to return to the country where he had received his university education. His place of exile was changed, however, at the insistence of the Governor of Perm, who had once been a friend of Apollo in St. Petersburg. After traveling east for several weeks, the family was diverted to the more severe Vologda, 250 miles northeast of Moscow. Like many Polish patriots who remained faithful to their political principles and moral convictions, Apollo and Eva were thrown into the wilderness of penury and prison.

Conrad’s friend and collaborator Ford Madox Ford later recorded an incident that took place in May 1862: “The oldest—the first—memory of his life was of being in a prison yard on the road to the Russian exile station of the Wologda. ‘The Kossacks of the escort,’ these are Conrad’s exact words, repeated over and over again, ‘were riding slowly up and down under the snowflakes that fell on women in furs and women in rags. The Russians had put the men into barracks the windows of which were tallowed. They fed them on red herrings and gave them no water to drink. My father was among them.’ ”

The family soon had to suffer far worse than cold and thirst, for both Conrad and Eva became seriously sick en route. When Conrad fell ill with pneumonia, near Moscow, the guards refused permission to break the journey. While the protesting parents refused to move, a sympathetic traveler sent a doctor from the city, who arrived in time to save the child. Apollo related that after the doctor had applied leeches and calomel (a purgative) and Conrad began to feel better, the guards started to harness the horses: “Naturally I protest against leaving, particularly as the doctor says openly that the child may die if we do so. My passive resistance postpones the departure but causes my guard to refer to the local authorities. The civilised oracle, after hearing the report, pronounces that we have to go at once—as children are born to die.”

They were still traveling east toward Perm when Eva became ill at Nizhni Novgorod. The family asked permission to stay there until she recovered; though the request was refused, they gained a few days before turning north to Vologda. After a five-week journey, they arrived on June 16. In Under Western Eyes, Conrad described the vast, formless Russian landscape in which he had traveled and lived: “Under the sumptuous immensity of the sky, the snow covered the endless forests, the frozen rivers, the plains of an immense country, obliterating the landmarks, the accidents of the ground, levelling everything under its uniform whiteness, like a monstrous blank page awaiting the record of an inconceivable history.”6

Though it is not clear why the Korzeniowskis took Conrad into exile instead of leaving him comfortably in Poland with his grandmother or his uncle, Eva probably could not bear to part from her frail only child and Apollo may have wanted him to experience the suffering that would turn him into a Polish patriot. Whatever their reasons, Conrad certainly shared their anxiety, grief, poverty, hardship and sickness. The governor of Vologda, Stanislaw Chominski, was a kindly man, able to fulfill the duties of his office and yet maintain a humanitarian attitude toward the twenty-one Poles, mostly priests, under his authority. Though his treatment of the prisoners was quite tolerable, the severe climate took its toll.

The penal town, east of St. Petersburg and north of Moscow, on the Moscow–Siberia road, was spread out on both sides of the Vologda River. It had been founded in the twelfth century, when a monastery and a wooden church were constructed; a cathedral and Roman Catholic chapel were built later on. First defended by a wooden palisade and then by a stone fort, Vologda had traded furs and timber with England and Holland during the sixteenth century. Its large market-place sold hides, tobacco, eggs, grain and salt fish, and its factories made candles and furs. In 1861 the population was 16,500, including a number of Polish exiles from the revolutions of 1830 and 1846, who had been allowed to return home after the accession of Alexander II in 1855, but had married, become acclimatized and remained in northern Russia.

Apollo provided a personal and bitter description of the harsh and hostile physical conditions in a long letter of June 27, 1862:

What is Vologda? A Christian is not required to know. Vologda is a huge quagmire stretching over three versts [two miles], cut up with parallel and intersecting lines of wooden foot-bridges, all rotten and shaky under one’s feet: this is the only means of communication for the local people. . . . A year here has two seasons: white winter and green winter. The white winter lasts nine and a half months, the green winter two and a half. Now is the beginning of the green winter: it has been raining continually for twenty-one days and it will do so till the end.

During the white winter the temperature falls to minus twenty-five or thirty degrees and the wind blows from the White Sea. . . .

The air stinks of mud, birch tar and whale-oil: this is what we breathe. . . . All one does is pray with confidence and blind faith, although common sense says that prayers from here can never reach heaven and that God always looks another way, or else the view of the world would become too repugnant for Him. . . .

Is it not better to die here? As a memory, exile and death will provide a better and more substantial evidence of service to the cause of truth and of one’s beloved country than the return of someone driven to desperation by homesickness, rotten, and carrying that rottenness back home. . . . We do not regard exile as a punishment but as a new way of serving our country. There can be no punishment for us, since we are innocent.7

In October, after white winter had arrived, Apollo described the savage iciness and the difficulty of heating the crude, low-pitched log house: “We are bitterly cold here. For the last couple of days we have had plenty of snow. Firewood is as expensive as in Warsaw, and the number of stoves equals that of the windows, so we must heat furiously; but even when the stoves are red-hot, after several days of frost a white moss appears in the corners of the warmest of dwellings.” The historian Edward Crankshaw, who visited Vologda in recent times, confirms the crude conditions and the insalubrious climate: “It was, and still largely is, a wooden town with streets and sidewalks of logs built on a swamp in the back of beyond, a station on the railway running east from St. Petersburg, or Leningrad, to the Urals. The people of the surrounding district are very poor indeed, and the summer climate is wretched and unhealthy into the bargain.”8

The Korzeniowskis were supported in Vologda by remittances from Eva’s brother Kazimierz. And Apollo’s hot-house religious patriotism was the main consolation for shattered hopes in that remote penal settlement. His nationalistic sentiments led to one of Conrad’s earliest pieces of writing (probably dictated by Apollo, who may also have guided his hand) on the back of a photograph taken in Vologda: “To my dear grandmother who helped me to send cakes to my poor father in prison—Pole, Catholic, gentleman. July 6th, 1863. Konrad.” In The Arrow of Gold, Captain Blunt, a South Carolina supporter of the Confederacy, repeats this autobiographical description when he claims, “Je suis Américain, catholique et gentilhomme.” Though Apollo was deadly serious in engendering these noble sentiments in his son, Conrad later classified them among the “absurd illusions common to all exiles,” and deflated his father’s ideals by declaring: “A class that has been under the ban for years lives on its passions and on prejudices whose growth stifles not only its sagacity but its visions of reality.”9

Apollo could bear his martyrdom, an essential part of the Polish patriotic tradition, as long as he felt that his sacrifice had not been entirely in vain and that there was still some hope for the rebellion he had planned but failed to carry out. All the political disappointments that had tormented Poles for the last hundred years—the decline of the nation in the late eighteenth century, the three partitions, the false expectations raised by Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812, the reinstatement of Russian rule after the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the failures of the revolutions of 1830 and 1846, the defeat of Polish hopes after the European risings in 1848 and the Crimean War in 1856—could (Apollo felt) have finally been remedied by the rebellion that broke out in January 1863, while he was suffering arctic temperatures of thirty degrees below zero.

But—like the insurrections of 1794, 1830 and 1846—the revolt of 1863, which Coleman calls “the most heroic, if ill-advised, armed uprising in all Poland’s history,” was doomed to failure when it challenged the overwhelming might of absolutist Russia. According to a legend that began in the eighteenth century, most Polish men dreamed of dying in a hail of rifle fire while leading a cavalry charge in a hopeless attack on foreign invaders. Balzac, who was well acquainted with the Poles, confirmed their self-destructive courage when he wrote in Cousin Bette (1846): “Show a precipice to a Pole and he’ll make the leap. As a nation they are like cavalrymen; they think they can overcome all obstacles and emerge victorious.” (This daring tradition continued until September 1939, when Polish cavalry charged Nazi tanks during the Blitzkrieg.) Conrad, writing to his Russophile friend Edward Garnett and attempting, as always, to distinguish Poles from other Slavs, contrasted Poland’s “delirium of the brave” with Britain’s confident expectation of victory: “you seem to forget that I am a Pole. You forget that we have been used to go to battle without illusions. It’s you Britishers that ‘go in to win’ only. We have been ‘going in’ these last hundred years repeatedly, to be knocked on the head only.”10

The 1863 rising, which began on January 22, was defeated by internal dissension as well as by external repression, for there were two violently antithetical political parties in Warsaw: the Whites and the Reds. Both were opposed to conciliation with the Czarist government and wanted to re-establish the pre-partition boundaries of Poland. But while the Whites, protecting their material interests, tried to undermine revolutionary feeling and postpone the revolt to the indefinite future, the Reds—Apollo’s party—advocated land reform, the abolition of serfdom and immediate revolutionary action. The Whites were supported by the gentry and the prosperous middle class; the Reds by students, intellectuals, clergymen, workers and the lower middle class. In The Rainbow (1915), D. H. Lawrence describes the political background of Lydia Lensky and her husband, who fled to England after the defeat in 1864: “They represented in Poland the new movement just begun in Russia. But they were very patriotic: and, at the same time, very ‘European.’ . . . Then came the great rebellion. Lensky, very ardent and full of words, went about inciting his countrymen. Little Poles flamed down the streets of Warsaw, on the way to shoot every Muscovite.”

Vladimir Nabokov’s grandfather Dimitri—aide-de-camp to the Czar’s brother Constantine, who had been appointed viceroy of Poland in 1862—helped to suppress the rebellion that was incited by Conrad’s father. Davies explains the immediate cause and eventual extent of the rising:

[The Russian viceroy could] smell a rebellion, but was unable to trace its source. He decided to force it into the open. His chosen instrument was the Branka, or “forced conscription.” After saturating the Kingdom with 100,000 troops, he prepared to draft 30,000 young men into military service. . . . The Branka was timed for 14 January 1863. It was the immediate cause of open hostilities. . . .

[The Poles] did have a fully fledged political programme, an extensive financial organization which was already raising funds, and the cadres of an underground state. . . . He was faced from the start by a guerrilla war, which was master-minded by unseen hands from within his own capital, and which kept Europe’s largest army at bay for sixteen months. . . .

Of the two hundred thousand Poles who were estimated to have carried arms during the Rising, there were never more than thirty thousand in the field at any one time. Most of them were scattered among hundreds of partisan bands operating in all the woods and wildernesses of the land. In the sixteen months that the Rising lasted, 1,229 engagements were fought—959 in the Kingdom, 237 in Lithuania, the rest in Byelorussia and the Ukraine.

In 1863 Ivan Turgenev, the only Russian writer Conrad admired, told a friend: “It is impossible not to wish for the speediest suppression of this senseless rebellion.”11 The Poles’ hopes for foreign intervention were disappointed; Warsaw was paralyzed by dissension; and the partisan groups in the countryside dissolved and were eventually destroyed. The repression was severe, and all the leaders were captured and hanged. The uprising had been a costly failure that had destroyed the finest elements in the nation and provoked even greater repression.

In 1864 a policy of Russification was adopted: “the tsar and the bureaucracy took the decision to administer the Polish areas as occupied territory in which the inhabitants of Polish speech were to enjoy a minimum of civil rights.” The rising left permanent scars in Poland, where a whole generation were deprived of their careers and their future. After 1864 there was no longer any hope for a successful revolution, and “the Franco-Prussian War and the Eastern crisis in the seventies finally removed the Polish question from the agenda of European diplomacy.”12

The Korzeniowskis’ immediate family suffered terribly from the defeat. Apollo’s father died on the way to join the Partisans. His older brother, Robert, was killed during the insurrection. His younger brother, Hilary, a hunchback, was arrested just before the rising and died in Siberian exile in 1878. And the remnant of the Korzeniowski fortune was confiscated by the Russian government. His maternal uncle Tadeusz, fond of contrasting the cautious conservatism of the Bobrowskis with the reckless defiance of the Korzeniowskis, was opposed to the rising. He naïvely believed that Poles should place all their hopes in the “noble impulses” of Alexander II, thought there was absolutely no hope of defeating the Russians and wrote: “Without exaggeration it may be stated that the events of 1861–63 were begun in falsehood and that they ended in falsehood.”

Yet his younger brothers Kazimierz and Stefan were as radical and as violent as Apollo. Kazimierz was imprisoned during the rising and Stefan, the underground commander in Warsaw, directed the revolutionary government and kept the struggle going. Najder asserts that Stefan “was killed on 12 April [1863] in a duel provoked by his right-wing opponents,” but it was actually Stefan himself who provoked the duel. He called Count Grabowski (a leader of the Whites) a reactionary who had plotted against the revolution and wanted it to fail. Grabowski, cleared of the charge of treachery in a court of honor, asked Stefan to withdraw the accusation. When Stefan refused to do so and repeated the charge, the two men quarreled, a duel became inevitable and Stefan was mortally wounded.13

Apollo’s response to the rising was a rambling and repetitive, passionate and prescient political essay, “Poland and Muscovy,” which was smuggled out of Russia and published in an émigré journal in Leipzig in 1864. Its aim was to warn the European powers of the Russian threat to civilization. Apollo begins with a vitriolic account of his imprisonment and trial; he condemns Russia as the “terrible, depraved, destructive” embodiment of barbarism and chaos, as “the plague of humanity” and “negation of human progress”; he describes Russia’s horrible oppression of Poland during the last century; and he concludes with the idea—repeated in Conrad’s “Autocracy and War”—that the historical mission of humane, Catholic, democratic Poland is to protect their natural allies in western Europe from the destructive hordes of Moscow:

The whole of Moscow is a prison. Beginning with the Ryryks [ninth-century founders of the Russian monarchy], and then with the Tartar thraldom, the oppression of Ivan, under the knouts of various tzars and empresses and so forth, Muscovy has been, is and always shall be a prison—otherwise it would cease to be itself. In that prison committed crimes and flourishing deceit copulate obscenely. The law and official religion sanctify these unions. Their offspring: the falseness and infamy of all religions, of all social, political, national and personal relations. . . .

Ninety years ago the European governments and nations looked on impassively as swarms of locusts descended on the most fertile fields, as the miasma of the most sordid and lethal plague spread, as seas of foul muck poured over the fruits of the earth, as barbarism, ignorance, renegation swallowed up civilization, light, faith in God and in the future of mankind; in short, it all happened when Muscovy seized Poland.

Apollo’s frightening conception of Russia, “unrestrained, organized and ready to spew out millions of her criminals over Europe,” was developed by Conrad in The Secret Agent and Under Western Eyes. And the idea of the barbaric “Tartar whip and tzarist knout” recurs in The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann (a great admirer of Conrad) when the liberal Settembrini, alluding to the notorious prison in St. Petersburg, warns Hans Castorp: “Asia surrounds us. . . . Genghis Khan. Wolves of the steppes, snow, vodka, the knout, Schlüsselburg, Holy Russia. They ought to set up an altar to Pallas Athene, here in the vestibule—to ward off the evil spell.”14

In January 1863, the year of the fatal rising, Apollo was granted permission, on grounds of poor health, to move farther south to a less extreme climate. The family resettled in Chernikhov, eighty miles north of Kiev, where they remained for the next five years. In an atmosphere extremely hostile to Poles, Apollo continued to work on his translations. Despite the improved conditions, his wife’s health began to deteriorate. In the summer of that year Eva’s brother, who had served in the Russian Guards, used his influence to arrange a three-month “leave of absence” so that she and Conrad could get medical treatment and visit the family estate at Novofastov, between Berdichev and Kiev.

That summer—when Conrad played with his young cousins, first rode a pony and met his great-uncle Nicholas Bobrowski (who had fought with Napoleon and became the hero of Conrad’s story “The Warrior’s Soul”)—seemed the happiest time in his life. Yet in A Personal Record, he recalled his mother’s illness and connected it to the oppressive political conditions:

I did not understand the tragic significance of it all at the time, though indeed I remember that doctors also came. There were no signs of invalidism about her—but I think that already they had pronounced her doom unless perhaps the change to a southern climate could re-establish her declining strength. . . . Over all this hung the oppressive shadow of the great Russian Empire—the shadow lowering with the darkness of a newborn national hatred fostered by the Moscow school of journalists against the Poles after the ill-omened rising of 1863.

When the leave expired and Eva was too ill to return to exile, the provincial governor threatened to send her under escort to the prison hospital at Kiev. As they rode off in an open trap, harnessed with three horses, the tearful French governess who had taught him to read and speak his first foreign language, cried out: “N’oublie pas ton français, mon chéri.”

In late February 1865, Apollo described his wife’s terminal illness, which he ascribed to psychological suffering and to lack of proper medical treatment, and mentioned the disastrous effect this had on little Conrad:

My poor wife, who these last two years has been destroyed by despair and by the repeated blows that fall on members of our joined families, for the last four months terribly—gravely ill, has barely the strength to look at me, to speak with a hollow voice. This state has been caused by the lack of everything for the body and the soul—no doctors, no medicines. Today she is allowed to go for treatment to Kiev but her lack of strength makes it impossible. . . . I am unable to satisfy, help or console my poor patient. Konradek is of course neglected.

Ten days later, when the crisis deepened, Apollo was more specific about her hemorrhages and mentioned “a sudden consuming fever, a lung condition and an inner tumour, caused by an irregular blood flow, requiring removal. . . . [The doctor] sees the operation as imperative but cannot perform it owing to her lack of strength. . . . The lung disease becomes more menacing. . . . There is a threat of death from every side.”15 On April 18, 1865, Eva died of tuberculosis in Chernikhov at the age of thirty-two. The seven-year-old Conrad, who witnessed her agonizing decline, was devastated by the loss. Apollo was also tormented by the guilty feeling that his arrest and exile had been largely responsible for Eva’s death.

The death of his mother, the second great turning-point (after exile) in Conrad’s childhood, weakened his own frail health and threw him into morbid conjunction with his father. As a boy, Conrad was pale, delicate, unstable and epileptic; as an adult, hypersensitive, intensely nervous and frequently ill. He had inflammation of the lungs in May 1862, en route to Vologda, and again in 1863. Three years later, he had a series of epileptic attacks. In June 1868 he suffered from what Apollo called a new onset of his old illness: urinary deposits in his bladder that caused constant stomach cramps. And in his early teens he had severe migraine headaches and nervous attacks.

Apollo gives a terribly depressing account of his solitary existence with Conrad. After the failure of the revolution and the death of his wife, his courage gave way to despair. He devoted himself to his son, but was not an effective teacher; he tried to protect Conrad from the pernicious Russian influence, but realized he was stifling the child by cutting him off from normal life; he tried to keep the memory of Eva alive, but was tormented by grief and guilt, which no penance, however harsh, could absolve:

Poor child: he does not know what a contemporary playmate is; he looks at the decrepitude of my sadness and who knows if that sight does not make his young heart wrinkled or his awakening soul grizzled. These are important reasons for forcing me to tear the poor child away from my dejected heart. . . .

Since last autumn my health has been declining badly and my dear little mite takes care of me. . . .

My life is, at present, confined solely to Konradek. I teach him all I know myself—alas, it is not much; I guard him against the influence of the local atmosphere and the little mite is growing up as though in a cloister; the grave of our Unforgettable is our memento mori and so every letter . . . brings us fastings, hair-shirts and flogging.

Apollo taught his son at home, partly because he did not want the delicate child to be educated in Russian schools. But Apollo was too demanding and Conrad, living in almost complete isolation, burrowed “too deeply” into books. Though Apollo frequently asked friends to send him school materials, he mentioned in 1868 that Conrad’s poor health, especially his epilepsy, had prevented him from studying during the past two years.

For a year and a half, from May 1866 until the autumn of 1867, Conrad was “torn” from Apollo while receiving medical treatment in Kiev, Zhitomir and Novofastov. In November 1866, Apollo wrote, with an element of self-pity: “I am lonely. Konradek is with his granny. . . . We both suffer equally: just imagine, the boy is so stupid that he misses his loneliness where all he saw was my clouded face and where the only diversions of his nine-year-old life were arduous lessons. . . . The boy pines away—he must be stupid, and, I fear, will remain so all his life!”16

Apollo was a poor estate administrator, a mediocre poet and a disastrous revolutionary—in short: a failure. These failures intensified his sacrificial patriotism, deepened his despairing mysticism and led to a morbid cult of his dead wife, all of which made life unbearably dreary for young Conrad. Apollo’s religion—his only hope in life, apart from his son—“was based on a kind of Christian stoicism rather than on reasoned belief. ‘Everything that surrounds me,’ “ he wrote from Chernikhov, “ ‘bids me doubt the existence of a divine omnipotence, in which I nonetheless place all my faith and to which I entrust the fate of my little one.’ ”

It is scarcely surprising that Conrad, from the age of thirteen (two years after Apollo’s death) rejected the doctrines, ceremonies and festivals of his father’s despairing religion. Later, he equated these beliefs and observances with Russians, especially with his bête noire Dostoyevsky, and dismissed them as “primitive natures fashioned by a Byzantine theological conception of life, with an inclination to perverted mysticism.” Writing to the atheistic Garnett in 1914, and thinking of his deluded and long-suffering parents, Conrad condemned Christianity as “distasteful to me”:

I am not blind to its services but the absurd oriental fable from which it starts irritates me. Great, improving, softening, compassionate it may be but it has lent itself with amazing facility to cruel distortion and is the only religion which, with impossible standards, has brought an infinity of anguish to innumerable souls.17

In January 1868 Prince Gollitzen, the Governor of Chernikhov, declared that the dying Apollo, after five and a half years in Russia, was no longer dangerous, and released him from exile. Apollo received permission to travel to Algiers and Madeira, but—living frugally on Eva’s inheritance, his modest literary earnings and handouts from the family—had neither the funds nor the energy to do so.

Austrian Poland, which recognized Polish nationality and allowed Poles civil rights if not political independence, was much freer than the parts of the country under German and Russian rule. In the Ukraine, for example, the school system had become thoroughly Russified after 1864; Polish, even in private conversation, was forbidden in school buildings. For these reasons, father and son moved west to Galicia, lived in Lvov, the provincial capital, for six weeks during January–February 1868, and then in the old royal and academic city of Cracow. In 1868 Apollo wrote that Conrad was having German lessons so that he could go to school. He passed the entrance examination for St. Anne’s Gymnasium, but probably attended St. Jacek’s school.

By the time they reached Cracow, Apollo was a desperately ill and mortally weary man—vanquished by disillusion, bereavement and gloom. Embittered by Galician indifference to the cause of Polish freedom, he told a friend: “I am broken, fit for nothing, too tired even to spit upon things.” In “Poland Revisited” (1915), Conrad—who had witnessed his mother’s slow death and now suffered the same experience with his father—gives a moving account of Apollo’s final weeks.

The last time Apollo was seen out of bed, propped up with pillows in a deep armchair and attended by nursing nuns in white coifs, he supervised the burning of some of his manuscripts. The atmosphere around his deathbed was an uneasy mixture of pity, resignation and silence:

My prep finished I would have had nothing to do but sit and watch the awful stillness of the sick room flow out through the closed door and coldly enclose my scared heart. . . .

Later in the evening, but not always, I would be permitted to tip-toe into the sick room to say good-night to the figure prone on the bed, which often could not acknowledge my presence but by a slow movement of the eyes, put my lips dutifully to the nerveless hand lying on the coverlet, and tip-toe out again.

On May 23, 1869, Apollo, like Eva, died of tuberculosis. His funeral turned into a patriotic demonstration by several thousand people. Conrad, emotionally exhausted and no longer able to cry, led “the long procession [that] moved out of the narrow street, down a long street, past the Gothic front of St. Mary’s under its unequal towers, towards the Florian Gate.” The words cut into Apollo’s gravestone were: “Victim of Muscovite Tyranny.”

Thirty years later, Conrad gave Garnett an idealized yet essentially negative portrait of his father:

A man of great sensibilities; of exalted and dreamy temperament; with a terrible gift of irony and of gloomy disposition; withal of strong religious feeling degenerating after the loss of his wife into mysticism touched with despair. His aspect was distinguished; his conversation very fascinating; his face in repose sombre, lighted all over when he [rarely] smiled. I remember him well. For the last two years of his life I lived alone with him.

Apollo was also the model for Heyst’s father in Victory, a kind of third-rate Schopenhauer whose books were ignored by the world and whose only disciple was his unfortunate son.

Søren Kierkegaard’s perceptive analysis of his own father’s destructive love illuminates Conrad’s final relation to Apollo as well as his portrayal of Apollo in Victory:

Once upon a time there lived a father and a son. Both were very gifted, both witty, particularly the father. . . . On one rare occasion, when the father looking upon his son saw he was deeply troubled, he stood before him and said: poor child, you go about in silent despair. (But he never questioned him more closely, alas he could not, for he himself was in silent despair.) Otherwise, they never exchanged a word on the subject. Both father and son were, perhaps, two of the most melancholy men in the memory of man.

And the father believed that he was the cause of the son’s melancholy, and the son believed that he was the cause of the father’s melancholy, and so they never discussed it. . . . And what is the meaning of this? The point precisely is that he made me unhappy—but out of love. His error did not consist in lack of love but in mistaking a child for an old man.

The pervasive gloom of the Kierkegaards and the Korzeniowskis was characterized by a melancholy atmosphere, mutual unhappiness, lack of understanding, poignant silence and bitter despair. “Conrad’s father must have seemed to him at once awe-inspiring and absurd; his attitude towards him was a mixture of admiration and contemptuous pity. And he could never forgive his father the death of his mother.”18 Apollo’s legacy to Conrad was a volatile temperament, an anguished patriotism, the bitterness of shattered hopes, the trauma of defeat and a deep-rooted pessimism.

After Apollo’s death, Conrad became the ward of his uncle Tadeusz Bobrowski, who grew wheat and sugar beet on an estate at Kazimierowka, about thirty miles southeast of Zhitomir. Tadeusz was short and balding, with sharp Roman features and a bushy beard. A fussy, pedantic but essentially kind-hearted man, he was the temperamental antithesis of Apollo, and had the mind and cautious character of an accountant. He had married in 1857 and ten months later, when his wife died in childbirth, was left a widower and the father of a frail little girl. She had been treated in various spas and had died, at the age of thirteen, in 1871. Tadeusz, who had a completely different set of values, replaced Apollo and became Conrad’s surrogate father. He transferred all his affection to the orphaned child of his beloved sister, and looked after his education, moral progress and material welfare. At the end of a long financial account in 1876, Tadeusz wrote: “the upbringing of Master Conrad to manly status has cost (apart from the capital sum of 3,600 roubles given him) 17,454 roubles”—about $25,000. After Tadeusz’s death, Conrad called him a distinguished man of powerful intelligence and great force of character, who had cared for several wards and had had an enormous influence among conservative landowners in the Ukraine.

Conrad remained in Cracow: during the first year in a pension for boys run by Ludwik Georgeon, a veteran of the 1863 rising, on Florianska Street; and during the next three years at his grandmother’s flat on Szpitalna Street. During this time he was frequently in poor health, attended school irregularly and was tutored by a medical student at Jagiellonian University in Cracow, Adam Pulman. Conrad and his tutor spent the summers of 1870–72 at Krynica, in the Carpathian mountains, southeast of Cracow; and during the spring and summer of 1873 they traveled in Switzerland, Bavaria, Austria and northern Italy. In a Swiss boarding-house, Conrad first heard English spoken by some British engineers who were helping to build the St. Gotthard Tunnel. Though Conrad claimed that he had never seen the sea until he arrived in Venice with Pulman, he had actually visited Odessa, on the Black Sea, with Uncle Tadeusz in the summer of 1867. But in his memoirs, he wanted this crucial experience to be associated with the Mediterranean rather than with Russia. In 1881 Tadeusz wrote Conrad that Pulman had tricked many people out of money and refused all demands for repayment. But after Pulman’s death, five years later, at the age of forty, Conrad recorded that all “the bereaved poor of the district, Christians and Jews alike, had mobbed the good doctor’s coffin with sobs and lamentations at the very gate of the cemetery.”19

During the Cracow years, the solitary, hypersensitive and well-read young Conrad impressed friends by memorizing and reciting long passages from Mickiewicz’s Pan Tadeusz and by writing patriotic plays, like The Eyes of Jan Sobieski, in which Polish nationalists defeated the Muscovite enemy. Pleased with himself and accustomed to the undivided attention of his parents, Conrad once disturbed an adult conversation with the egoistic question: “ ‘And what do you think of me?’ To which the reply was: ‘You’re a young fool who interrupts when his elders are talking.’ ” Conrad’s distant cousin in Lvov, with whose family he lived in 1873–74, later described his intelligence, ambitions, Apollo-like sarcasm, desire for freedom, informal manners and ill health:

He stayed with us ten months while in the seventh class in the Gymnasium. Intellectually he was extremely advanced but disliked school routine, which he found tiring and dull; he used to say that he was very talented and planned to become a great writer. Such declarations coupled with a sarcastic expression on his face and with frequent critical remarks, shocked his teachers and provoked laughter among his classmates. He disliked all restrictions. At home, at school, or in the living room he would sprawl unceremoniously. He used to suffer from severe headaches and nervous attacks; the doctors thought that a stay at the seaside might cure him.20

Conrad left high school early in 1874 without finishing the course. An indifferent scholar, he had studied some Greek, Latin and German, Polish Romantic literature, mathematics, history and his favorite subject, geography. But he had also read widely on his own, especially books on distant voyages and exotic exploration. Hugo’s Toilers of the Sea, and adventure novels by Captain Marryat and Fenimore Cooper inspired him to become a sailor. Like Lord Jim, he was attracted to the adventurous aspects of nautical life and lived “in his mind the sea-life of light literature. He saw himself saving people from sinking ships, cutting away masts in a hurricane . . . always an example of devotion to duty, and as unflinching as a hero in a book.” Conrad may also have been drawn to Cooper who, in his appeal “To the American People,” had nobly supported the Polish cause after the revolution of 1831:

The crime of Poland was too much liberty. Her independent existence, in the vicinity of those who had reared their thrones on the foundation of arbitrary will was not to be endured. Fellow Citizens, neither the ancient institutions nor the ancient practices of Poland have been understood. The former had, in common with all Europe, the inherited defects of feudal opinions, but still were they among the freest of this hemisphere.21

Though Conrad’s motives for leaving Poland were extremely complex, he had good political and personal reasons for going into voluntary exile. He believed the 1863 rebellion had been a pointless and unqualified disaster. When he left Russian Poland in 1874, his country had suffered more than one hundred years of servitude and had absolutely no prospects for independence. Like Apollo, Conrad found the enormous Russian garrison, the despotism of petty officials and the extreme hostility to all things Polish oppressive and intolerable.

Conrad’s sense of humiliation, his bitterness and anger, could never be extinguished. Speaking of Poland later in life, he told friends: “[I] spring from an oppressed race where oppression was not a matter of history but a crushing fact in the daily life of all individuals, made still more bitter by declared hatred and contempt. . . . I can’t think of Poland often. It feels bad, bitter, painful. It would make life unbearable. . . . [The Russian] mentality and their emotionalism have always been repugnant to me, hereditarily and individually.”22 Conrad felt his family had suffered sufficiently; he wanted to escape from what he rightly considered a hopeless political situation. He loved Poland as a memory of the past, but her present frightened him and her future looked like a dark abyss. It is essential to emphasize and to remember the most crucial facts of Conrad’s early life: the Russians had enslaved his country, forbidden his language, confiscated his inheritance, treated him as a convict, killed his parents and forced him into exile.

His motives for going to sea were both practical and romantic. A family physician, fearing that Conrad might die of the same tuberculosis that had stricken his parents, believed he could be saved by living near the sea and getting plenty of physical exercise. He had been thrilled by the Black Sea at Odessa and by the Adriatic at Venice. Inspired by reading fictional sea adventures, he had as a child wanted to enter the marine cadet school at Pola, across from Venice, in Austrian Croatia. He found Austria the most liberal and least antipathetic of the three powers ruling Poland, had some sympathy for the Hapsburg dynasty and wished to serve in the Austrian navy. But when his application for Austrian citizenship was refused, he was unable to enter the school.

Conrad’s destiny was also determined by another practical consideration. As the son of a political convict, he was liable, when he reached military age, for conscription into the ranks of the Russian army for twenty-five years. Conrad had to leave Poland. His question, like Razumov’s in Under Western Eyes, was: “Where to?”

Ever since Adam Mickiewicz and Frédéric Chopin had left the country after the rising of 1831, France, the enemy of Russia and Austria, had become the traditional, congenial refuge of Polish exiles. Conrad spoke French, his family had some useful contacts in Marseilles and he could join the French merchant marine in that pleasant Mediterranean seaport. So he decided to reject Apollo’s sacrificial legacy (“Be a Pole!”) and to cut himself off from the tragic past of his landlocked country. On October 13, 1874, the sixteen-year-old Conrad became one of the three and a half million emigrants—including his close contemporaries Ignacy Paderewski and Marie Sklodowska Curie, as well as Guillaume Apollinaire (né Kostrowitsky), Lewis Namier and Bronislaw Malinowski—who left Poland between 1870 and 1914. Like Jasper Allen, the handsome hero of “Freya of the Seven Isles,” Conrad, “an old man’s child, having lost his mother early, [was] thrown out to sea out of the way while very young, [and] had not much experience of tenderness of any kind.”23