In his book The Riddle of the Sands, published in 1903, Erskine Childers – one-time Royal Naval officer and fervent Irish nationalist, who was to die at the hands of a Free State firing squad and to whom the whole genre of the modern spy novel can be ascribed – presented the contention that Imperial Germany was making preparations to invade England’s east coast with a seaborne invasion issuing from the small harbours laying in the shallow waters behind the East Frisian Islands.

In the book, the German efforts are frustrated by two young British yachtsmen who, while sailing the waters around and behind the low-lying islands of Borkum, Norderney, Baltrum, Langeoog and the twisting torturous channels and sandbanks between the River Ems and the Weser, expose the German invasion plan and alert their government to the danger.

At a time of increasing international tension, the publication of the book caused great excitement and disquiet both in the general public and in Parliament, where rapid German naval expansion was being viewed with increasing concern. Although there was in reality no such invasion plan in the German archives emanating from the Frisian Islands, there had earlier in 1894 been a plan for a seaborne invasion that had briefly been considered by the High Command, but was already abandoned by 1900.

However, the hypothesis expressed most forcibly in the novel was that the east coast and its ports that faced Germany across the North Sea were at that time almost totally unprotected, lacking any form of effective defence and open to invasion. The reason why the coast from Norfolk to the north of Scotland was so thinly defended by defensive works or coastal batteries has a long historical origin.

For the preceding five centuries or longer any seaborne threat to these islands had come from our traditional enemy, France, together with Spain, and for a period the Dutch in the 1600s.The geography of these threats necessitated positioning British major naval bases and defences mainly along the south coast at harbours where they could concentrate their naval strength, such as Dover, Portsmouth, Plymouth and Torbay, and from where the ‘wooden walls’, taking advantage of the prevailing westerly winds, would be in an advantageous position to sail out before the wind to keep watch and blockade the French ports of Brest, L’Orient, La Rochelle and other harbours.

Historically, British control of the narrow seas was so complete that any landing on Britain’s eastern shores seemed a remote possibility, although with changing alliances such threats did occur.

During the Dutch Wars in the 1650s–70s, for instance, English control was sorely contested, with defeats at sea. In 1667 the Dutch fleet, sweeping aside the paltry defences, sailed up the Medway, burnt the shipyard at Chatham and captured or destroyed sixteen ships.

By 1900, although there were existing fortifications and batteries controlling the entrances to the major seaports, advances in naval gunnery meant that modern warships far outperformed the obsolete artillery installed in most of these shore batteries that could no longer offer the protection to Britain’s shores, as had been the case in the past. The 3-mile limit – the distance of a cannon shot – that for centuries had been the arbiter of our safety was now no longer a shield against infection and the hand of war.

The paradox was that, following the rapid expansion of the German fleet after the ratification of the First Navy Law in 1898 under Tirpitz’s direction, and the British response, the Royal Navy found itself with an ever-growing fleet of huge modern battleships that, under the strategy for their use, dictated that they largely operated as a single unit to maximise their massive destructive power and ability to completely overwhelm any opposition.

The need to concentrate such a huge assembly of ships required the need to find a suitably large anchorage to accommodate them, and at the same time to be in a geographically advantageous location that answered to the strategic requirements of our naval policy.

By 1900 the requirement for a new naval base to control the east coast became ever more urgent and coincided with the recognition that in a future war the close blockade of enemy, or more particularly German ports, by our ships would be impractical and undesirable due to the developments of modern weapons such as long-range artillery, the mine and the development of fast torpedo boats and, latterly, submarines that could threaten capital ships. The new policy of distant blockade also required that the German fleet should be effectively contained within the North Sea or preferably within its harbours so as not to offer a danger to our merchant fleets on the world’s trade routes.

In March 1904 the Prime Minister Arthur Balfour announced to the House of Commons that a new naval base was to be established at Rosyth on the Firth of Forth where the main battle fleet, then referred to as the Home Fleet, would in future be based.

From here it was suggested the Royal Navy could exert control over the German fleet and their bases in the German Bight some 350 miles across the North Sea.

The choice of Rosyth as a base had many advantages: being near to the cities of Dunfermline and Edinburgh across the Firth, there was an availability of labour to construct and service the port. Moreover, it was connected by the main rail line to all other parts of the country for the supply of materials, munitions, coal and so on.

A disadvantage to the location was voiced early in the scheme by the First Lord Admiral Fisher and others, who objected on the grounds that it lay on the upstream side of the great iron Forth railway bridge, which, should it be damaged or destroyed in an attack or through some act of sabotage, would effectively trap the entire fleet, rendering it impotent.

Fisher also suggested that the long and relatively narrow sea entrance to the proposed harbour rendered it vulnerable to the laying of mines and attacks from torpedo craft in a similar manner to that experienced by the Russians at Port Arthur at the hands of the Japanese.

Progress on building the base over the next few years proceeded slowly, as there were conflicting views both in Parliament and at the War Office, as well as the Admiralty, as to the value or the necessity of building it at all.

The influential Admiral Fisher, in the throes of developing his revolutionary fleet of dreadnought battleships and completely reorganising the Royal Navy from the top down to make it fit for purpose under the changed conditions, considered Rosyth to be unsuitable, being too far inland. Instead, it favoured the more northern Cromarty Firth, or the River Humber, and expressed his opinion that Rosyth was an unsafe and poor choice for a fleet anchorage.

The defence of harbours and ports devolved on the War Office, as did the protection of naval storehouses, building facilities and magazines – a situation that was far from satisfactory, as the amount of money the War Office was prepared to expend fell far below that necessary to adequately ensure their security.

By 1912 the strategy of the distant blockade had become the accepted plan to be employed. In the event of war with Germany, and while the narrow waters of the English Channel were seen to be adequately taken care of by the naval forces at Harwich, Dover and Portsmouth, the gap between Scotland and Norway required further northern bases to be developed.

Belatedly, work on Rosyth and the Cromarty Firth were accelerated with a minimum of shore-based artillery being installed, sufficient only to fend off light enemy forces, but at the time inadequate to repel any determined attack. The rate of progress and lack of political will to complete these bases left them largely unfortified at the outbreak of war in 1914.

The other anchorage being considered was Scapa Flow, a vast body of enclosed water in the Orkney Islands at the northern point of the Scottish mainland, covering 120 square miles of protected water, and considered to be one of the great natural harbours in the world.

Separated from the Scottish mainland by the Pentland Firth, Scapa Flow consists of 10 miles of stormy water where daily tides flow between the North Sea and the Atlantic at a rate of between 8 to 10 knots. The tides also flow strongly in and out of the various entrances, making navigation difficult when, as frequently occurs, sea fogs, mists and storms beset the anchorage, particularly in winter, when due to its northerly position the short days mean the Flow can be in darkness for up to 18 hours a day.

It has a fairly shallow (around 50 to 100ft in depth), sandy bottom and three main entrances: Hoy Sound to the west and Hoxa Sound to the south, a mile wide and used during the Great War as the main entrance and exit for the fleet. Apart from other very much smaller entrances used by fishermen, the Switha entrance leading in to Longhope Sound was used as the base for trawlers and other boats such as boom vessels that were required for the management of the anchorage.

Scapa Flow had been used as a harbour since historical times, being known to the Romans and the Vikings, and King Haakon IV of Norway anchoring his fleet there in 1263 before the Battle of Largs, in an attempt to reassert Norwegian rule over northern Scotland. This came to nothing when the Scottish forces of King Alexander III beat them off, ending Norwegian control.

During the flight of the Spanish ships around the wild rocky coastline of Scotland following the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, several unfortunate vessels were cast ashore on its inhospitable coastline.

Scapa Flow had previously been used since the 1890s by ships of the Royal Navy for summer fleet exercises, and from 1909 under Fisher’s directions more frequent use was made of it, with the Home Fleet using it as the base for exercises from April to October.

In 1909 no less than eighty-two warships were anchored in its environs, consisting of thirty-seven pre-dreadnought battleships and cruisers including the new Dreadnought, supported by forty-four destroyers, colliers and repair and store ships.

The following year, ninety warships under the command of Prince Louis of Battenberg, including battleships, cruisers and destroyers, conducted summer manoeuvres and night-firing exercises during August and September from Scapa Flow. In 1911, with the international situation worsening again, the anchorage was used for naval exercises, with destroyer and cruiser flotillas conducting practice torpedo attacks and countermeasures exercises, while the battleships practised deploying from cruising formation to line of battle, and firing exercises in the Atlantic.

Even though up to the outbreak of war Scapa Flow was extensively used by the Royal Navy, the thought of using it as a permanent war station was not seriously considered until 1912 when the policy of the distant blockade had been reluctantly accepted by a Liberal government who were unenthusiastically supporting the massive naval rearmament programme, and who were anxious to cut expenditure in other areas to save money.

At the time Scapa Flow was being considered as a base, it was completely lacking in any form of defence and there was no will within Parliament to expend vast sums on making it safe.

At the same time, the discussions on the various merits of Scapa, Rosyth and Cromarty were seemingly endless and served only to put off any decision on a final choice of a preferred base.

At Scapa, apart from the light guns landed with the Royal Marine Artillery during exercises and a few field guns used by the local Territorial Army artillerymen, the islands were without any other form of defence. Furthermore, apart from the town of Kirkwall and the even smaller community of Stromness, there were no social amenities on the islands to cater for the off-duty crews or any dockyard facilities to service and repair the ships.

In 1912 a proposal was made to mount twenty-four guns and searchlights to secure the harbour, but nothing came of this. It was only in 1913, with a further change of plan after Winston Churchill had belatedly announced in Parliament that Cromarty had been chosen as the preferred major North Sea base, that work at last started, much to the relief of all concerned.

The parsimonious attitude towards expenditure on the construction of new harbour facilities and coastal defences was in contrast to the German approach to the problem, where, following the introduction of the larger dreadnought battleships into their fleet, they had constructed new docks of larger dimensions which allowed for ships of greater beam than their British counterparts to be built and, therefore, possessed of greater protection. Over a seven-year period they had also spent millions of marks in enlarging and deepening the Kiel Canal to allow the rapid passage of their ships between the North Sea and the Baltic, while at the same time installing modern protective batteries and forts.

In Britain the naval defence estimates year by year, while providing the necessary money to build new dreadnoughts, were lacking in the provision for new harbour construction or their defence. British naval estimates for 1913–14 were a massive £46,500,000, of which as little as £5,000 was set aside for improvement work to Scapa Flow.

The Admiralty requested £380,000 for the installation of what they considered minimum defences to secure the anchorage, but even this cost, the price of a destroyer, was turned down by the Liberal chancellor Lloyd George as being too expensive. So, when war broke out, the fleet found themselves entering what was the ideal anchorage, but wholly unprotected from the enemy.

As the British fleet departed Portland on 29 July for their war station, colliers had already been sent ahead, together with fleet oilers and supply and repair ships, anchoring in protected inlets to form the basis of a real base.

The first to drop anchor were the destroyers of the 4th Flotilla, returning from duty in the Irish Sea, where tensions were high with the continuing Home Rule problem that had seen opposing groups arming for a possible confrontation.

The battle fleet arrived on 31 July, with the great ships entering through Hoxa Sound to anchor in lines off Scapa pier on the north side of the Flow off Flotta Island, their arrival largely concealed by a fog, and the last ships arriving in the short hours of the summer night.

By 1 August, Scapa Flow was the home to ninety-six ships, with three battle squadrons consisting of twenty-one dreadnoughts, eight pre-dreadnoughts and four battle-cruisers.

The Commander-in-Chief Admiral Sir John Jellicoe flew his flag in the Iron Duke with the 1st Battle Squadron under Vice-Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly, composed of Marlborough flag, with ten 13.5in guns and seven dreadnoughts with ten 12in guns.

The 2nd Battle Squadron contained eight of the later 13.5in super-dreadnoughts, with Vice-Admiral Sir George Warrender flying his flag aboard the King George V. The 3rd Battle Squadron was made up of eight pre-dreadnoughts, each mounting four 12in guns, with Vice-Admiral E. Bradford commanding aboard the King Edward VII.

The 1st Battle-Cruiser Squadron was under the command of Vice Admiral Sir David Beatty and comprised the Lion, Princess Royal, Queen Mary and New Zealand. Also present were eight armoured cruisers, thirteen cruisers and forty-two destroyers. Overnight the population of these remote islands had swollen by 40,000 souls. Also under the command of the Commander-in-Chief was the Channel Fleet based at southern harbours and on the south coast, commanded by Vice-Admiral Sir Cecil Burney and composed of the 5th, 6th, 7th and 8th Battle Squadrons, containing twenty-eight pre-dreadnought battleships armed with four 12in guns apiece.

It is customary for modern writers to regard these older ships as useless, but, while inferior to the dreadnoughts in gun power, they performed much valuable work during the war.

The first task at Scapa Flow was to strip the ships for action, with any unnecessary woodwork and fittings, wardroom furniture or any other fire hazards, together with spare boats that were surplus to requirements, taken ashore and dumped. Although now installed at his northern base, Jellicoe (as had been his predecessor Admiral Callaghan), was deeply concerned by the lack of defences and was afraid of the possibility of an attack by either German destroyers or submarines.

He immediately stationed destroyers at the entrances to the Flow and instituted cruiser patrols off the islands. His confidence was hardly improved when the cruiser Birmingham rammed and sank the U-boat U15 in the first few days of the war off Fair Isle.

Alarmed by the dangers of an unprotected anchorage, Jellicoe took the fleet to sea in the first few weeks, as he felt his ships would be safer and in October he took the entire fleet to Lough Swilly on the north-west coast of Ireland while boom defences and gun emplacements were hurriedly installed, until by November Jellicoe was at last satisfied that the anchorage was secure.

The old battleship HMS Hannibal was permanently anchored to cover the entrance into Hoy Sound, while her sister ship HMS Magnificent was similarly positioned to protect Hoxa Sound. In addition, several old ships were sunk as block ships in the smaller entrances on the eastern side of the islands to discourage U-boats. Other anti-submarine measures included commandeering dozens of fishing trawlers equipped with light guns and towed explosive sweeps that could be detonated from the ship. The trawlers laid the steel anti-submarine nets of the boom defences and electrically controlled mines were also laid, which between them registered two successful sinkings.

On the morning of 24 November 1914, the U18 commanded by Kapitan von Hennig attempted to enter the Flow through Hoxa Sound, but her periscope was sighted by a patrolling trawler and rammed her, though not fatally. The damaged U-boat tried to run for home but had to be scuttled near the Pentland Skerries, where her crew were rescued by British destroyers.

Later, near the end of the war, great advances had been made in the protection of the entrances, with arrays of hydrophones installed to detect incoming submarines, and on 25 October 1918 a mine-laying submarine, the UB116, also attempted to enter Hoxa Sound. She was detected by hydrophones and was quickly destroyed when an electric mine was triggered from the shore. There were no survivors and it was the last German U-boat to attempt an entrance until Gunther Prien’s successful sinking of the Royal Oak in October 1939.

The island of Flotta was taken over and began to be developed as the on-shore headquarters establishment, with piers and an oil storage and ammunition dump being established. An athletics ground and a football field were constructed for the recreational use of the men, where games and boxing tournaments were entered into with great enthusiasm and in an intense spirit of competition between ships’ crews, while a nine-hole golf course was dug for the officers on the exposed treeless island that was frequently used by the Commander-in-Chief when he went ashore.

Other amenities added as the years went by included a much appreciated cinema and a YMCA hut that gave a welcome taste of the civilian world and a break from the strict naval discipline that prevailed on board ship. When the weather permitted, sailing and rowing regattas were a pleasurable diversion from the monotony of the regular and everyday duties.

Within the Flow, the battle fleet lay off Flotta Island, often in appalling weather conditions, when frequent gales struck the islands where the ships rode out the storm with both anchors down. Fog and rain were a regular part of the scene, with each ship isolated from its fellows when the sea state was too rough for boats to be lowered to visit neighbours.

Much praise must be given to the work of the attached steam drifters, manned by Scottish fishermen, who in all but the very worst weather continued their important work of delivering mail, provisions and supplies from the depot ships at Long Hope, while each day the attached minesweepers put to sea to clear the swept channels.

Once a month, one of the battle squadrons would leave the Flow in rotation to sail down to Invergordon on the Cromarty Firth, which now belatedly was fully protected with guns and anti-submarine nets. Here conditions were more bearable for the crews, and the off-duty liberty men were able to enjoy some of the more normal everyday pleasures of life in a large town, such as pubs and cinemas, and the company of females available in the average seaport that were so lacking at Scapa Flow.

From here the same routine of training prevailed, with the Squadron putting to sea on North Sea sweeps, on the receipt of intelligence reports, searching for the elusive enemy, which all too often involved steaming at high speed at action stations, only to find the intelligence in error or that the alerted enemy had long slipped away.

The Grand Fleet through constant exercise were working the crews up to a high degree of efficiency, and at sea during battle practice the guns were fired at targets and signal-flag and wireless communications and the complicated manoeuvres necessary to deploy the fleet were practiced over and over again.

At any time the battleships and cruisers of the fleet needed to put to sea for battle practice, while the destroyers, between their duties in screening the larger warships from submarine attack, also had to take part in weapons training and tactical exercises in co-ordinated flotilla attacks and night-fighting training.

The process of organising the Grand Fleet to put to sea, whether for practice or North Sea sweep, was a complicated operation that required careful planning and timing, with instructions being sent to the various units to raise steam many hours before the indicated departure time.

The destroyer flotillas would be dispatched first to form a protective screen for the big ships, while the patrol vessels already at sea would be searching for any U-boats that might be laying off the approaches to the harbour.

Next, the cruiser squadrons and the armoured cruisers that were to scout ahead of the battle squadrons would depart to their rendezvous points and, finally, the battleships were ordered to sea by divisions.

Sometimes these operations would take place at night, often in atrocious weather conditions, with perhaps sixty ships showing no lights, steaming at speed into the darkness, with the danger of collision an ever present threat, requiring the highest standards of seamanship to accomplish successfully.

A line of twenty-four battleships at sea in the closest order would be 6 miles in length and, although this line of battle would be the preferred formation that an admiral would want to present to an enemy as he crossed his line of advance, putting him in the advantageous position of crossing the enemy’s T, it had severe disadvantages. For instance, to pass a flag signal from one end to the other could take 10 minutes and such a line would be the ideal target for a submarine attack.

Prior to disposing into line of battle, the fleet would adopt the cruising formation, where, for instance, twenty-four ships would form six columns of four ships in line ahead disposed abeam of each other, forming a compact box where signals could be more rapidly communicated.

The problem was to effect a smooth transition from this compact formation into the battle line, which was dependent on the direction the enemy approached. Only constant practice to cater for all possible variations could bring the ships and crews to the highest standard of efficiency.

The German High Seas Fleet in 1914 was composed of thirteen dreadnought battleships, comprising four Westfalen class ships – these being the first German dreadnoughts built and launched in 1909, mounting twelve 11in guns, together with four similarly armed Helgoland class of 1911, armed with twelve of the heavier 12in guns, and five Kaiser class of 1913 which, with a superimposed turret arrangement aft in the manner of the British Colossus class, carried ten 12in guns. There were also ten pre-dreadnought battleships, each with four 11in guns, and four modern battle-cruisers carrying ten 11in guns.

The German battleships had greater displacement than their British counterparts, class for class, as well as thicker armour protection and, while the calibre of the main armament was less in each case, thanks to the superior subdivision of their hulls and watertight integrity their ability to absorb punishment was greater. The provision in their construction of additional armoured longitudinal and transverse bulkheads to protect their vitals was superior to that found in the British ships, and rendered them almost unsinkable.

During 1915 the fleet were joined by three ships of the new and powerful Queen Elizabeth class, carrying eight of the new Mk1 45 calibre 15in gun that fired a shell of 1,920lb at a muzzle velocity of 2,575ft per second to a range of 30,000yd. The three ships were HMS Queen Elizabeth, HMS Warspite and HMS Barham, each of 32,000 tons’ displacement and with a length of 640ft.

With geared turbines of 75,000hp they could achieve 25 knots and were not only remarkably fast, but were also more heavily armoured than earlier classes, with 13in belt and 6in armour to the upper deck, 2in anti-torpedo protection and later retrospectively fitted with anti-torpedo bulges. They were joined in 1916 by HMS Valiant and HMS Malaya, which was a gift from the Government of Malaya.

These ships formed the 5th Battle Squadron of the Grand Fleet and were considered to be the most effective and successful British battleships ever built and gave sterling service in both World Wars. They were oil fired, and the extra 4 knots allowed them to be used as a fast battle squadron that supported Sir David Beatty’s battle-cruisers most effectively at Jutland.

The name ship Queen Elizabeth was sent shortly after completion to the Dardanelles in 1915 to assist in reducing the Turkish forts during efforts to force the narrows, but was soon withdrawn after receiving hits from Turkish batteries, as it was considered to be too hazardous and an ineffectual way to employ such a modern vessel that had cost £2,400,000 to build.

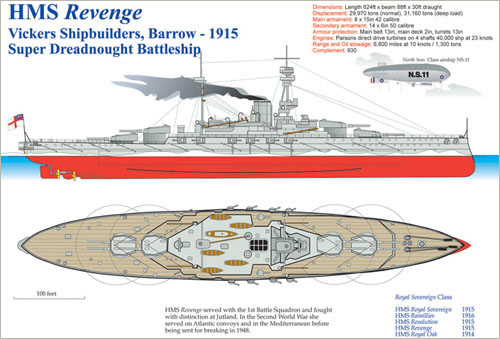

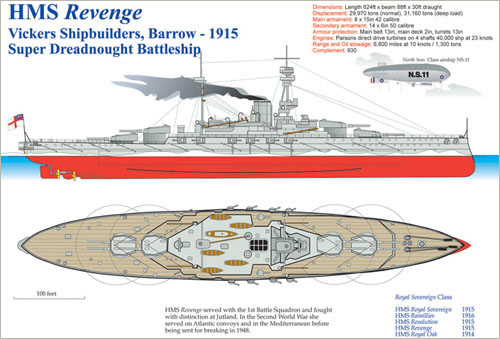

The following class were the Royal Sovereigns, which entered service in 1916–17. They were originally designed as 21-knot coal-burning versions of the Queen Elizabeth class, as there was concern over the possible interruption of oil supplies during a conflict, whereas Britain had all the secure reserves of coal required to serve the needs of the fleet.

The Revenge, Royal Oak and Royal Sovereign joined the fleet in May 1916, allowing the first two ships to be in action at Jutland on 1 May 1916, while Resolution and Ramillies joined the 1st Battle Squadron at Scapa in late 1916. These ships had only eighteen boilers, compared to the Queen Elizabeths’ twenty-four, reducing the horse power from 75,000 to 40,000, which, with the change to oil-fired boilers, gave the very respectable speed of 23 knots.

The length of this class of ship was reduced to 620ft, while the tonnage remained approximately the same, with the reduction of the number of boilers allowing for the installation of a single funnel, giving these ships a distinctive outline. They were regarded as having too low a freeboard and proved to be very wet forward in heavy weather, with a tendency to roll heavily, but, like their predecessors, they were to serve with great distinction in both world wars.

As the war progressed into 1915, with newer battleships and cruisers being added to the fleet, our strength increased with further units of the Iron Duke and King George V class being added, together with the purchase of HMS Canada in October 1915 that was being built for Chile as the Almirante Latorre of 32,000 tons armed with ten 14in guns, unique at that time in the British fleet. The Canada was present at Jutland with the 4th Battle Squadron, where she made good practice on the German line.

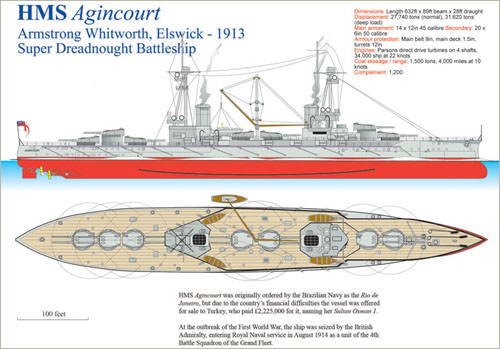

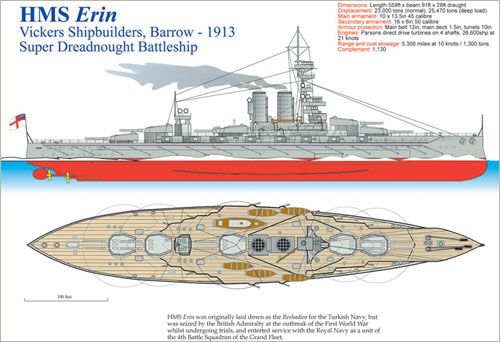

This ship was subsequently sold back to Chile in 1920, together with three modern Tribal class destroyers, for £1,400,000. Two other acquisitions made in 1914 were the Agincourt and the Erin. Both these ships had been under construction for Turkey.

The Agincourt had originally laid down as the Rio de Janeiro for Brazil, but due to financial difficulties in that country it was offered for sale to Turkey for £2,225,000. She was renamed Sultan Osman I. This was a powerful vessel of 27,750 tons, 632ft in length, and her Parsons direct drive turbines of 34,000hp gave her a speed of 22 knots.

At the time of her launch she was considered the largest and most heavily armed warship in the world, mounting fourteen 12in guns in seven turrets, each named for the days of the week, although her armour protection was poor, with only a 9in main belt and as thin as 1.25in deck armour.

At the outbreak of war Turkey had paid £2,000,000 for the vessel, almost crippling the country financially in the effort, but the British Government was alarmed at the prospect of so powerful a battleship coming into the hands of a potential enemy and seized her from the Armstrong Whitworth yard at Elswick, sending her to Devonport Royal Dockyard for completion.

HMS Agincourt joined the 4th Battle Squadron at Scapa Flow in August 1914, later serving at Jutland in the 1st Battle Squadron, firing 144 12in shells at the enemy while receiving superficial damage herself. After a life of ten years, the Agincourt was scrapped in 1924.

The second ship, HMS Erin, had also been commissioned by the Turks for Vickers Shipbuilders Barrow as the Rashadiea and was complete and running sea trails, with a Turkish crew waiting ready to sail for home, when it was also seized by the Royal Navy in August 1914, entering service with the Grand Fleet. The Erin was very similar in layout to the King George V class and with her ten 13.5in guns was a welcome addition to the fleet.

With these additions, the 3rd Battle Squadron of pre-dreadnoughts under Vice-Admiral Bradford, which was comprised of ships of the King Edward VII class, was withdrawn from Scapa in April 1915 to be based at Sheerness, as a support to the Harwich Force should there be further German raids on the east coast.

Of the six ships in this class the King Edward VII was sunk by a mine off Cape Wrath in 1916 and the Britannia had the misfortune to be the last British battleship sunk in the war in November 1918 off Cape Trafalgar.

With the advent of the entry of the United States into the war on 6 April 1917 as a result of the German policy of resuming unrestricted submarine warfare, the US Navy sent a squadron of dreadnought battleships to be attached to the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow in December of that year.

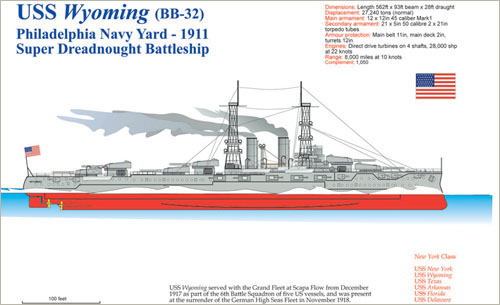

The squadron consisted of the flagship USS New York, USS Wyoming, USS Texas, USS Arkansas, USS Florida and USS Delaware, together with escorting cruisers and destroyers, which soon had their own anchorages in the Flow. The ships were under the command of Rear Admiral Hugh Rodman, where they formed the 6th Battle Squadron of the Grand Fleet.

The American ships worked up to full efficiency in a remarkably short period of time to achieve the same high standards as the Grand Fleet. Their arrival was greeted as a welcome addition by the war weary crews, who had for the past four years kept the watch on the German fleet in their harbours across the North Sea. The American ships were employed on convoy duty and joined the other ships of the Grand Fleet on their regular North Sea sweeps. The flagship New York rammed and sank an enemy U-boat in the Pentland Firth on one of these patrols.

The New York class ships were of 27,240 tons’ displacement, with a length of 562ft and a beam of 93ft. Their armament was rather mixed, with New York and Texas carrying ten 14in guns, while Wyoming and Arkansas were fitted with twelve 12in guns and Florida mounting only ten 12in guns, but with all ships carrying a 5in-gun secondary armament.

Direct drive turbines of 28,000–30,000hp gave the ships a speed of 22 knots. Their oil fuel gave them a radius of action of 8,000 miles and they carried a crew of 1,050. Their characteristic wire-cage masts were a distinguishing recognition feature of these American ships. The six ships of the squadron were also present as representatives of the US Government at the surrender of the German High Seas Fleet in November 1918. Equally important as the battleships were the support vessels that allowed them to operate efficiently far from their well-equipped home dockyards. The fleet repair ships were mobile workshops that could provide spare parts and repair facilities, being fully equipped with forges and machine tools that could cope with all but the most serious mechanical problems that would need to be carried out in a dry dock at a main naval base. A floating dock was, however, towed up to Scapa Flow, where it was able to take the largest of the fleet’s battleships and proved a great asset throughout the war.

Five fleet repair ships were commissioned from converted merchantmen, not all of which worked at Scapa Flow. They were HMS Aquarius 2,800 tons, HMS Assistance 9,600 tons, HMS Bacchus 3,500 tons, HMS Cyclops 11,500 tons and HMS Reliance 3,250 tons. Of these most were sold at the end of the war, while Cyclops was converted to a submarine depot ship and continued in use, serving throughout the Second World War, being finally scrapped in 1947.

Destroyer depot ships were often old cruisers, but ex-merchant ships were deemed more convenient for use due to the larger compartment spaces available. Five converted merchant ships were in use from 1913 onwards. They were HMS Diligence 7,400 tons, HMS Greenwich 8,584 tons, HMS Hecla 5,600 tons, HMS Sandhurst 11,500 tons, HMS Tyne 3,590 tons and HMS Woolwich 3,400 tons, with Greenwich and Sandhurst surviving to serve in the Second World War.

The submarine depot ships were also originally eight or so old cruisers, but were substituted for the same reasons when suitable merchant ships became available as follows: HMS Ambrose 6,400 tons, HMS Lucia 5,800 tons, HMS Pandora 4,500 tons, HMS Titania 5,250 tons, HMS Adamant 935 tons, HMS Alecto 1,600 tons and HMS Maidstone 3,600 tons.

Mine laying was initially conducted by old converted warships, but it soon became apparent that high speeds were required to reach the locations in enemy waters in the hours of darkness and to get clear before daylight. Accordingly, destroyers, fast cruisers and submarines were increasingly used for this duty, together with fast cross-channel ships including two Canadian Pacific Railway steamers, HMS Princess Irene and HMS Princess Margaret, each carrying over 400 mines. The dangers inherent in performing these duties were demonstrated when the Princess Irene blew up at Sheerness in 1915 while loading mines.

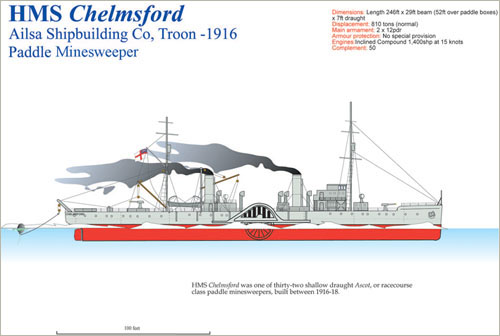

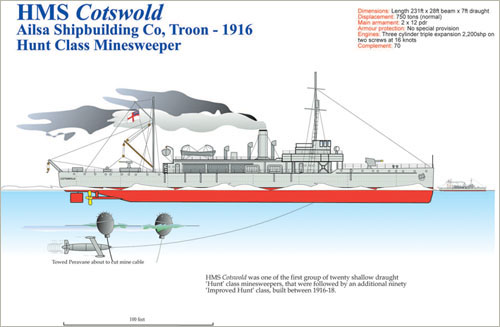

Minesweeping was carried out by a variety of craft, with trawlers and steam drifters being employed in large numbers, that were augmented by over one hundred Hunt class and a further thirty-six paddle minesweepers designed to work in the shallow waters of estuaries.

Over 200 sloops were also built during the war that gave invaluable service, being used for convoy escort work and for a variety of other duties, including minesweeping, anti-submarine duties and as Q ships to counter the U-boat menace. The Flower class sloop Azalea was typical of the type, being of 1,200 tons’ displacement, 262ft in length, with a beam of 33ft and powered by a four-cylinder triple expansion engine of 2,400ihp on a single shaft, giving a speed of 16 knots. Offensive armament consisted of two 4in or 12pdr guns and depth charges, with a complement of eighty officers and men.

Other smaller craft included the small steam-driven patrol or PC boats, eighty or so being built of around 600 tons, specially designed to hunt down U-boats and equipped with a hardened steel ram in the bows and carrying a 4in gun and two torpedo tubes. Turbines of 4,000ihp gave a speed of 23 knots.

Numerous Motor launches served on varied duties with the fleet, many of these being built in the USA being of 35 to 40 tons’ displacement.

CMBs were developed from pre-war racing motor boats to become the basis of a new type of fast torpedo boat, built largely at small yards on the Thames such as Thornycroft. The 70ft-long CMB of 24 tons, powered by 1,500ihp petrol engine, could reach 30 knots, carrying five torpedoes and six Lewis guns with a crew of six.