Probably the most charismatic class of ship, and the one that excited the imagination of the public on both sides of the conflict, was the destroyer or torpedo boat. They were produced in their hundreds, essential for the work of defending the larger and more valuable ships of the fleet such as the battleships.

A destroyer was small and fast, dashing into the attack under a storm of shells that left towering columns of water erupting around her, with thick black smoke pouring from her funnels and a great white bow wave curling away from her prow, as she heeled into a turn to deliver a torpedo attack on the enemy line, or to beat off an attack of enemy torpedo boats. Their dashing exploits were the stuff of legend on both sides in the Great War that spawned countless stories of heroism and called for a special type of officer and seamen to man them.

The early destroyers were cramped and uncomfortable, with the engines, boilers and machinery crammed into their narrow hulls, taking up most of the space below deck, and where the roaring furnaces, escaping steam from the boilers and thundering machinery, as the little ship pitched and rolled as it sped forward, made conditions in such a small space almost unbearable for the crews.

With the introduction of the Whitehead torpedo into the world’s navies in the 1870s, various experiments were conducted in its use, being initially installed in battleships as a defensive weapon to be used against other battleships. Later, small steam picket boats were equipped to launch torpedoes against an enemy fleet at anchor, which was seen as their main tactical use, but the range of the early torpedoes was limited and the boats themselves too small and slow.

In the 1880s many foreign navies started to build larger, fast and highly manoeuvrable torpedo boats, seeing this as a relatively cheap way to counter the advantages of an enemy that possessed more battleships by using a flotilla of torpedo boats to attack warships in their harbours.

The threat of the torpedo boat in the 1880s and the increasing range of the torpedo itself required battleships and cruisers to mount batteries of 4in quick-firing breech-loaders as secondary armament as a defence against torpedo attack. In the late 1880s a new type of boat was introduced specifically to deal with the torpedo boat, known initially as the torpedo boat catcher or torpedo gun boats, being larger and more heavily armed than their prey.

The Sharpshooter of 1888 was a typical torpedo gunboat of the period, being of 730 tons’ displacement, 230ft in length and armed with two 4.7in quick-firers, four 3pdrs and carrying five 14in torpedo tubes. Although they appeared to be a solution to the problem due to their large size, they proved to be slower than the torpedo boats they were set to catch.

An improved type of craft was devised with the building in 1887 at the Yarrow yard in Poplar of what was to be the first true torpedo boat destroyer. The Kotaka (Falcon) was built for the Japanese Navy according to their specifications, being of 203 tons and armed with four 1pdr guns and six 14in torpedo tubes. Kotaka was shipped out to Japan in parts, where she was assembled at Yokosuka Naval Arsenal, being capable of 20 knots and able to operate with the fleet at sea, where she participated in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95 and the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05. Her builders, Yarrow, later stated that they considered that Japan had invented the modern destroyer.

With the continuing development of high-pressure boilers and ever more powerful triple expansion reciprocating engines, the speed of the new torpedo boat destroyers now being introduced rose rapidly, but they were often susceptible to mechanical breakdowns and unable to keep up top speed for prolonged periods of time.

In 1885 the Spanish Admiralty placed an order with the George Thomson Shipyard on Clydebank for a torpedo boat, the Destructor, with a displacement of 380 tons and armed with one 6pdr and four 3pdrs and capable of 22.5 knots. Upon completion, the Destructor made the passage from Falmouth to El Ferrol across the Bay of Biscay, demonstrating her sea-keeping qualities in a record 24 hours, making her the fastest ship in the world at the time. The design of the ship was said to have influenced the naval constructor Sir William White in the design concept for later destroyers.

It was not until the launching of HMS Viper in 1889, powered by Charles Parsons steam turbine machinery, that the Royal Navy had a vessel that could maintain sustained high speeds for long periods and was almost vibration free and quieter, which was a welcome relief to the crews, who in the earlier boats had to endure the constant thundering gyrations of the reciprocating engines. Viper was capable of over 33 knots and even 37 knots under forced draught, an astonishing speed for 1889 when a battleship like the Canopus could only manage 17 knots.

The Viper was of 375 tons, being 223ft on the waterline by 20ft beam and carried one 12pdr quick-firer on the foredeck, two 6pdrs and two 18in torpedo tubes, with turbines of 11,500hp. She had a whaleback forecastle, with a diminutive open bridge platform and narrow walkways past the boiler uptake casings that served as decks, while the combination of low freeboard and high speed ensured that she was a very wet ship inside and out and, as with the earlier boats, her interior was still crammed full with steam pipes, boilers and engines that left little space for crew accommodation or any semblance of comfort.

Following the success of the Viper, the Admiralty ordered forty-two boats to a similar specification from fourteen different builders between 1889 and 1902 that varied in aspects of design and layout, although the specified armament was universal.

The early Whitehead torpedo of the period had a range of around 3,000yd at 26 knots, carrying a warhead of 200lb of explosive. However, with the introduction of the heater torpedo in the early 1900s, performance had greatly improved so that by the outbreak of the First World War the British Mk X 21 torpedo of 1914 had a range of 8,000yd at 38 knots, carrying a warhead of 500lb of Torpex, which greatly increased the destroyer’s offensive capacity.

This increased threat to capital ships was appreciated by commanders on both sides, dictating that in the event of a torpedo attack by destroyers the approved response was to turn away to allow the ships to comb the tracks. This method of dealing with an attack could result in the ships being attacked, losing contact with the enemy fleet if they were on a parallel course until it was safe to return to the original course.

So it could be seen that, even though a torpedo attack was unsuccessful, it could aid the tactical position of the retiring fleet by increasing the distance between them and allowing them a better chance of escape. It should be noted that a turn towards a torpedo attack was also available to the commander, allowing him, conversely, to gain on his retiring enemy while avoiding torpedoes, but this was generally considered to be a more risky manoeuvre and rarely employed in action.

The main builders of the new destroyers and torpedo boats were some of the smaller boat builders, such as Thornycroft, Yarrow and Hawthorn, while larger yards like Denny and Palmers also produced their own designs. The first class of torpedo boat destroyers delivered during 1893–95 were the A class of 27-knot turtle-backs. These boats were between 180 and 206ft in length, with a beam of 20ft and a draught of 12ft.

As stated, coming from a variety of builders, they varied in detail, but their average displacement was between 200–300 tons. Their machinery consisted of two sets of triple expansion engines with water tube boilers, developing 4,000hp on two shafts to give a speed of a very respectable 27 knots. Their armament comprised one 12pdr gun on the turtle back forecastle, plus three to five 6pdrs and two 18in torpedo tubes and carried a complement of fifty-five.

All of these first-generation destroyers served in the First World War, largely on coastal patrol and harbour protection work. Only one, HMS Lightning, was lost to mines and two others sunk as result of collisions.

Several of these vessels were sent out to serve on the China station, a long voyage, which says much of these little ships for their sea-keeping qualities, if not for their crew comfort.

Between 1895 and 1902, seventy-six larger turtle-back destroyers were added to the Admiralty list of the B, C and D classes of 30 knot boats,of gradually increasing size, with the D class being of between 310 to 440 tons, with a length of 210ft and a beam of 21ft.

The River class of 1903 was an attempt to improve the sea-keeping qualities of destroyers by giving them higher forecastles, in imitation of the German torpedo boats, and although these boats were slightly slower at 26 knots, this speed could be maintained in a seaway, where in the turtle-backs speed would fall off after a short period steaming at high speed. Armament was similar to the earlier boats, with one 12pdr quick-firer and five 6pdr guns being mounted.

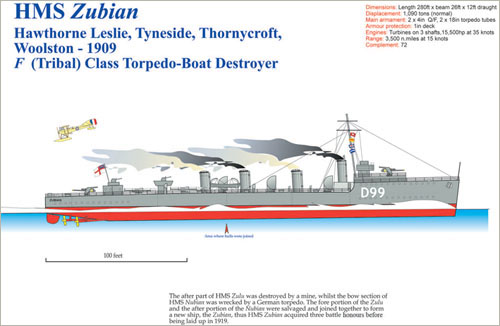

The first destroyers to be considered to be truly ocean going were the F class of 1907, these being the first of the famous Tribal class. In their design Admiral Fisher had insisted that they should be capable of 33 knots, and to achieve this speed required an unprecedented increase in power to 15,000hp, or twice that of the previous class. They were 270ft in length, with a displacement of 890 tons. Powered by turbine engines developing 13,000hp on three screws, these boats could reach 33 to 36 knots. They were more heavily armed than their predecessors, with five 12pdrs and two 18in torpedo tubes.

The Tribals were the first class to be oil-fired but had a limited fuel capacity of around 100 tons, and while they were excellent ships this defect limited their endurance due to their high fuel consumption. Of this group of ships, HMS Tartar reached 37.4 knots on her trials, making her the fastest ship of her day in 1907. All twelve ships of the Tribal class led active lives during the war, with HMS Ghurka being mined off Dungeness in 1917 and HMS Maori off Zeebrugge in 1915. Perhaps the most fascinating story involving these ships is the phoenix-like rebirth of two of them after being severely damaged in action.

On 21 October 1916 the destroyer HMS Nubian was coming to the end of her patrol off Folkestone when she was hit by a torpedo from a submerged U-boat, blowing off her bow. With her pumps working and the engine room still functioning, she remained afloat and able to proceed, being beached near Dover, where the wreck was examined by Admiralty inspectors.

Just over two weeks later, on 8 November, a second of the class, HMS Zulu, was mined off Gravelines, Dunkirk, blowing half her stern off. Again, the damaged ship remained afloat and was towed into Calais harbour. The Zulu had already led a busy life in the war, capturing the German barque Perhns on the first day of the war and later involved in almost continuous patrols in the Dover Straits and in supporting the coastal monitors bombarding German positions at the seaward end of the Western Front.

After inspection, Zulu and Nubian were both towed to Chatham dockyard, where fore section of Zulu and the after part of Nubian were joined together, despite there being a 4in difference in the beam of both vessels.

As Nubian, the newly created ship served throughout the remainder of the war with distinction, sinking the German mine-laying submarine UC50 off the Essex coast in 1916 by ramming and depth charge. The Nubian thus acquired three battle honours before being sent for breaking in 1919.

The ship that followed the Tribals was a one-off experiment built by Cammell Laird of Birkenhead as a flotilla leader and completed in 1907.

HMS Swift was almost the size of a light cruiser, being 2,200 tons’ displacement, with a length of 353ft and 34ft beam, with turbines of a massive 45,000hp. She could reach 40 knots, being originally armed with four 4in guns, with the two on the forecastle being replaced by a single 6in weapon in 1913, this being the heaviest gun mounted on a destroyer. Although she was referred to as the fastest ship in the Navy, she proved to be unsatisfactory, with recurring mechanical breakdowns and a high fuel consumption, at a speed of 27 miles per hour from a capacity of only 180 tons.

On 20 April 1917, together with HMS Broke, she engaged six German destroyers in the Dover Straits, during which Swift torpedoed the German destroyer G85 but received gunfire damage herself. In the meantime, the Broke had rammed the G42 where, with both ships locked together, hand to hand fighting broke out on the decks before the German crew of the sinking ship surrendered. The other four German destroyers retired from the action and the Swift went to the aid of Broke, rescuing the German crew of the sinking G42.

Originally planned by Admiral Fisher to be a new class of high-speed destroyer leader, and originally attached to the 4th Torpedo Boat Flotilla of the Grand Fleet, her performance was judged unsatisfactory, as were her sea-keeping qualities that made her unsuitable to operate with the fleet, despite her large size. No further boats of this class were built.

As war approached the Admiralty recognised the need for uniformity in the design of destroyers so that they could operate in flotillas of fifteen to twenty ships that would all have comparable performance.

The sixteen ships of the G or Basilisk class of 1910 conformed to this requirement and returned to coal-fired boilers, as it was considered that the supply of oil could be compromised in the event of war. These were the last British destroyers to burn coal.

These three-funnelled ships were projected under the 1908–09 estimates, and were 270ft in length with a beam of 28ft, making them roomier than the earlier ships. They displaced 900 tons, while turbines of 12,500hp on three shafts gave a speed of 28 knots. Armament consisted of a 4in Mk VIII breech-loading gun, three 12lb quick firers and two 21in torpedo tubes.

In order to improve their sea-keeping qualities, the bridge was placed higher and the bandstand which mounted the 4in gun was also positioned higher to fight in heavy seas.

The subsequent H class of twenty ships laid down in 1910, the I class of 1911 consisting of thirty ships, and the K class of a further twenty ships of 1913, were the last to be launched before the war and between them were the most modern destroyers available at its outbreak.

The L class were the first British class to exceed 1,000 tons’ displacement, at 1,072 tons, with engines of 24,000hp giving a speed of 31 knots, and were more heavily armed with three 4in guns and four 21in torpedo tubes. The effectiveness of these powerful destroyers was amply demonstrated on 17 October 1914 at the Battle of Texel when four L class destroyers, accompanied by a light cruiser, completely destroyed four German torpedo boats.

Following the Battle of the Heligoland Bight in August 1914, the High Seas Fleet were under orders to avoid further large-scale engagements, naval activity being reduced to the occasional coastal raid and minelaying in British coastal waters, where, despite the absence of German capital ships, their light forces continued to operate.

Performing a routine patrol off the Island of Texel at 2.00 p.m., the light cruiser Undaunted, commanded by Captain Cecil Fox and accompanied by the destroyers HMS Lennox, Lance, HMS Loyal and HMS Legion, encountered the German 7th Half Flotilla of four torpedo boats under the command of Korvettenkapitan Georg Thiele en route to lay mines in the Thames Estuary. As the British ships closed, the German torpedo craft made no attempt to challenge the approaching ships, nor was any attempt to retire initially made.

The British squadron was more heavily armed than the German ships, with Undaunted carrying two 6in guns and the four destroyers mounting three 4in guns apiece. The German torpedo boats S115, 117, 118 and 119, on the other hand, were of 1898 vintage and carried three 4pdr guns apiece, but did possess three 18in torpedo tubes that constituted a significant danger to the British squadron.

The German ships had at first mistaken the British ships for German reinforcements but, realising their mistake, began to scatter. By then, however, the Undaunted was within range and opened fire on S118, while Lance and Lennox attacked S115 and S119. Legion and Loyal joined the flagship in the pursuit of S118 and S117. Although the S119 managed to hit the destroyer Lance with a torpedo, it failed to explode and by 3.45 p.m. all four German ships were battered sinking wrecks. Total German casualties were four torpedo boats sunk, 300 killed and thirty prisoners taken, while on the British side losses were three destroyers damaged and five wounded.

A fortunate windfall from the encounter came when on 30 November a British trawler fishing the area recovered a lead-bound box containing German codebooks, which was delivered to code breakers in Room 40 at the Admiralty. This find aided the deciphering of future German secret messages.

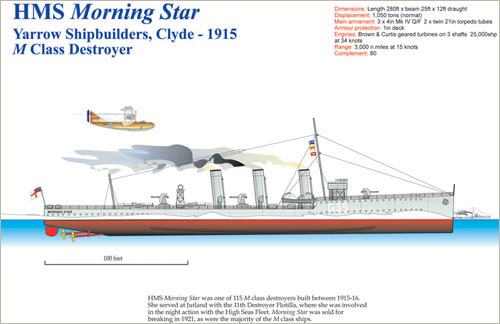

The larger M class that followed were produced in four groups. The first eighty-five ships, known as the Admiralty M class, were three-funnelled boats of 1,042 tons’ displacement, with turbines on three shafts delivering 25,000hp. Armament was increased over the previous group of ships to three 4in guns and four 21in torpedo tubes. Two other Hawthorn M types with two funnels and six Thornycroft Ms, with two funnels of similar displacement were also built.

Two further and very similar groups of ships, the R and S classes consisting of two funnels with geared turbines and capable of 36 knots, followed, making a grand total of 163 ships for the M, R and S groups.

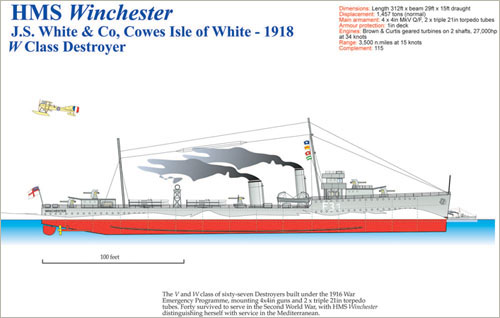

The following V and W classes represented a great step forward and were proportionally larger, being of 1,340 tons’ displacement, with geared turbines of 27,000hp They were of 312ft in length and 30ft beam and were true ocean-going destroyers, again armed with four 4in guns and one 3in gun, plus a heavier torpedo armament of six 21in torpedo tubes.

Fifty-one of this class were built, with the majority surviving to serve in the Second World War. These boats were designed to deal with the new generation of large German destroyers being built at the end of 1917, namely the V115 class, built as destroyer leaders and of 2,300 tons’ displacement, the size of a light cruiser. These large ships were armed with four 5.9in guns and four 23in torpedo tubes, plus the ability to carry forty mines at 37 knots. On paper, they were the most powerful destroyers in the world at that time and should have been formidable opponents, but in the event only two of the type was built, as they failed to come up to specification and were top-heavy, given to rolling badly in heavy weather.

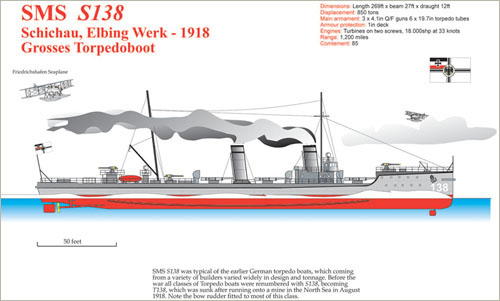

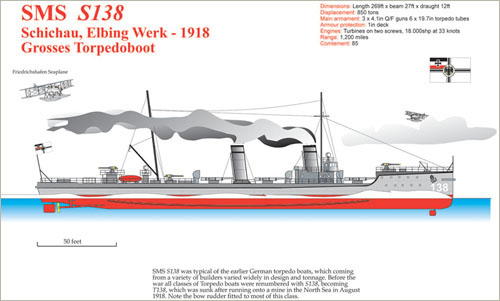

German destroyer development generally followed similar lines to the British, but favoured a heavier torpedo armament than their British counterparts. A typical example of the German torpedo boat was the S138 of 1906 that took an active part in the war, serving in the Battle of Jutland. The S138 (later renumbered T138) was built at the Schichau-Werke, Elbing. Completed in 1907, she was 269ft in length with a beam of 27ft and displaced 850 tons. Turbine propulsion of 18,000hp on two shafts gave a speed of 33 knots and had a range of 1,200 miles and a crew of eighty-five. To aid manoeuvrability, many of these ships were fitted with an additional rudder under the bow.

This particular torpedo boat was lost to a mine off Ostend in August 1918, not an unusual fate for torpedo boats and destroyers; the Royal Navy losing sixty-seven destroyers from all causes during the war.

At Jutland sixty-four German torpedo boats took part in the action where, surprisingly, considering the fierceness of the encounter, only five were lost against the eight British destroyers. For their time, they were exceptionally heavily armed, with three 4.1 Q/F guns and six 19.7in torpedo tubes and a 1in armoured deck.

The German torpedo flotillas at Jutland were bravely led and their torpedo attacks on Jellicoe’s battle squadrons on two occasions caused the British line to turn away, saving Admiral Scheer’s battleships from certain destruction.

The United States, with its need to maintain a presence in both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, was greatly aided by the completion of the Panama Canal in 1914 that enabled it to rapidly transfer warships from the east to the west coast or vice versa.

The US Navy similarly built large numbers of destroyers during the war which, class for class, were larger and possessed of greater range than contemporary German craft.

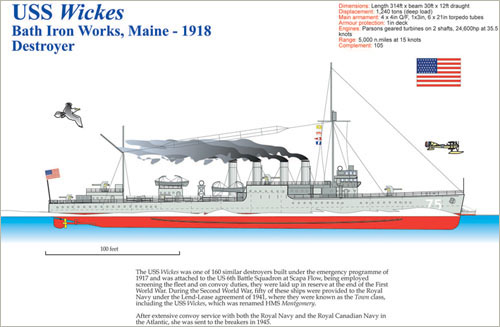

Of the destroyers that accompanied the US 6th Battle Squadron when it joined the Grand Fleet in November 1917, the USS Wickes was one of a class of no less than 111 ships, while with its great productive capacity between 1917 and 1923 under the War Emergency Programme eleven shipyards produced a total of 273 ships of a generally similar design, being flush decked and carrying four funnels, and known colloquially as four stackers.

The Wickes was large for a destroyer, having a length of 314ft and a beam of 30ft on a displacement of 1,240 tons. An armament of four 4in Q/F guns was carried, together with six 21in torpedo tubes. She carried a complement of 105 crew and had an exceptional range for the period of 5,000 miles. Engine power varied from 18,000 to 27,000hp and speed from 30 to 35 knots when new.

After the war most of this class of ships, after performing convoy duty work in the Atlantic and working with the Grand Fleet, were laid up in reserve, from where at the beginning of the Second World War under the Lend Lease agreement between Britain and the United States fifty of these ships were leased to the Royal Navy in exchange for 99-year leases on British bases in the Caribbean and elsewhere.

In British service they were known as the Town class, with the Wickes being renamed Monmouth and spending her service with the Royal Canadian Navy on convoy and patrol work, being finally sent to the breakers in 1946.

In May 1916 intelligence reports being analysed in Room 40 at the Admiralty in Whitehall indicated the High Seas Fleet were preparing to put to sea in force, which subsequently was to reveal itself as the great fleet action of the First World War: Jutland.

During this epic encounter the destroyer flotillas played an important and active part in the battle, where the way they were employed tactically ensured that they would find themselves invariably in a position of great danger between the two fleets. During the night action, the German fleet heading south-east towards its base at Wilhelmshaven crossed the rear of the British fleet that had been cruising on a divergent course seeking them. In the darkness in a time before the advent of radar, although only separated by 12 miles or so, the German ships passed behind the searching battle squadrons of the Grand Fleet to escape to safety.

In the aftermath of the battle and the perceived failure to punish the High Seas Fleet more fully, or indeed defeat it decisively, much criticism was levelled at the commanders of the scouting cruiser and destroyer groups that had made contact with the main portion of the German fleet in the darkness. They had failed to fully report these contacts in a comprehensive way that would make the situation clear to Admiral Jellicoe as he led the fleet towards the Horns Reef, where at 3.00 a.m. on the morning of 1 June he finally abandoned the pursuit and led his battle-damaged ships back to port.

Jellicoe was to complain in later years that the Admiralty had failed to pass on intercepted signals from the German fleet indicating Scheer’s position and speed, which they were reading in wireless traffic on an hourly basis and that would have been of incalculable value to the Commander-in-Chief. As the two fleets crossed their tracks a series of confused night actions occurred, with ships of opposing forces stumbling into each other in the darkness, where the brilliant glare of searchlights and the blast of gunfire close at hand were the first indications of the enemy presence.

Typical of these encounters was that of the 12th and 4th Destroyer Flotillas at 11.00 p.m. Captain Stirling aboard the flotilla leader HMS Faulknor commanding the Twelfth Flotilla was leading fourteen boats in the darkness, sailing on a gradually converging south-easterly course that was about to cross less than 4 miles behind the ships of the 1st and 5th Battle Squadrons and, unknown to Jellicoe, parallel to the leading ship of the retreating German line led by SMS Westfalen.

Six miles to the south-west, the Fourth Flotilla, commanded by Captain Wintour aboard HMS Tipperary, led the eleven boats of his flotilla in line ahead, comprising the destroyers HMS Spitfire, HMS Sparrowhawk, HMS Contest, HMS Garland, HMS Broke, HMS Achates, HMS Ambuscade, HMS Ardent, HMS Fortune, HMS Porpoise and HMS Unity.

At 11.00 p.m. Garland lookouts reported to Captain Wintour destroyers to starboard, but as they approached it became apparent that the ships were not destroyers but battleships. Unsure of the identity and nationality of the fast approaching ships, Wintour flashed the challenge. Almost immediately, Tipperary’s challenge was answered with dazzling searchlights illuminating his ship and a storm of shellfire. Within less than a minute, Tipperary was reduced to a blazing wreck, her bridge and all on it swept away in a blast of fire, as she fell out of the line.

In the darkness, the first five destroyers of the flotilla pressed home their torpedo attacks and opened fire with their deck guns, while the German battleships blasted away with their main armament at maximum depression because the range was so close. The Spitfire, next in line of the Tipperary, swung to starboard to avoid the wreckage of the blazing destroyer. Her captain, Lieutenant Commander Trelawney, then turned his ship to starboard to attempt to rescue the destroyer’s crew. As he did so, he unknowingly passed between the tracks of the first three German ships, when on his starboard bow he suddenly saw close at hand the towering bow of the second German battleship in the line, SMS Nausau, which, together with the other ships of the German 1st Battle Squadron having turned away from the torpedo attacks, were now turning to port to regain their south-easterly course.

Too late, the Spitfire attempted to avoid being run down by the massive battleship, but with a rending crash of metal the two ships came together port bow to port bow. As the Spitfire ground past the Nassau, the battleship depressed her forward 11in guns and fired a salvo at point-blank range that flew overhead, but the effect of the blast was powerful enough to wipe away the Spitfire’s bridge, killing most of her bridge crew and splitting her hull open like a tin can.

Scraping past her mighty opponent, the heavily damaged Spitfire drew off into the protecting darkness with 20ft of side plating ripped from the Nassau’s hull firmly wedged to her bow; evidence of her close encounter. Despite her grievous injuries, the damaged Spitfire limped home, and was subsequently repaired to fight again.

Although none of the British torpedoes had found a mark in the attack, the cruisers of the German Second Scouting group which had been accompanying the German battleships to port were thrown into confusion. After midnight, in the melee, the light cruiser SMS Elbing was in turn rammed by the battleship Posen, which tore a hole in her hull, flooding the engine room and the ship, although it was not in danger of sinking. A torpedo boat took off most of the crew and efforts were made to save the ship, but when enemy destroyers were sighted at 2.00 a.m. the captain ordered the Elbing scuttled, fortunately with only four of her crew lost.

The Fourth Flotilla now was under the command of Commander Allen in the Broke, which, followed by Sparrowhawk, Garland, Contest, Ardent, Fortune and Porpoise, now returned to the attack. Leading his force toward the German line, Allen sighted the cruiser Rostock. Once again the German line seized the initiative and the Fourth Flotilla was again swept by searchlight and a storm of shellfire, initially from Rostock and then from the 11in guns of Westfalen and SMS Rheinland.

The Broke was immediately reduced to a burning wreck, with her helm jammed hard to port and careering at high speed towards the unfortunate Sparrowhawk, which was turning to fire her torpedoes when the Broke crashed into her, locking both ships together.

The following ship, Contest, also managed to ram into the Sparrowhawk’s stern, where the blazing wreckage attracted still more unwanted attention of enemy ships, until the Broke drifted away. After a hazardous voyage of over two days, eventually made safety in the River Tyne.

The Sparrowhawk was taken in tow by the destroyer HMS Marksman but had to be abandoned the next day, while the Conquest also made it safely back to port and, after repair, re-joined the fleet to serve to the end of the war with honour.

The Fourth Flotilla still bravely pressed their attacks on the German line, but in so doing quickly lost the Fortune when again the Westfalen and five other battleships opened fire at close range. The Fortune was quickly reduced to a flaming wreck and sank, while the Porpoise was under heavy fire but managed to limp away to safety on the Humber.

The remaining ships of the flotilla scattered to save themselves, but not before Lieutenant Commander Marsden of the Ardent, attempting to escape, was also sunk as he once again blundered into the German line.

Despite all their bravery, and being responsible for two German cruisers being sunk, the Fourth Flotilla had been destroyed or scattered. Twice the ships of the Fourth Flotilla had bravely thrown themselves against the might of the German 1st Battle Squadron and their gallantry was in the highest traditions of the service.