By early 1916 a deep sense of frustration was being felt by the Lords of the Admiralty, politicians, the officers and men of the Grand Fleet and the general public alike at the seeming inability to bring the German fleet under the guns of the Royal Navy in a major sea battle that in everyone’s expectation, or at least that of the man in the street, would end in the destruction of the High Seas Fleet, creating a victory of Nelsonian proportions.

Time and again over the past twenty-one months, the Grand Fleet had put to sea on the receipt of some intelligence to seek out their opposite numbers across the North Sea, but when the German ships had briefly emerged from their harbours to raid Britain’s east coast or carry out some other operation off the Norwegian coast – due to bad communication or just bad luck – the British ships would arrive in the area of action too late to force a decision, allowing the High Seas Fleet frustratingly to slip away to safety.

The commander of the High Seas Fleet at the outbreak of war had been Admiral von Ingenohl, who was replaced following the Battle of the Dogger Bank in January 1915, where he was held responsible for the debacle, and for other losses that had occurred in the early months of the war.

His replacement, the former Chief of Naval Staff Admiral von Pohl, was under strict orders from the Kaiser that he should not risk the fleet unnecessarily, and that all future major operations should be personally approved by the Kaiser before being implemented.

Under these restrictions, the naturally cautious von Pohl conducted an even more timid policy throughout 1915, seldom ordering the fleet to venture more than 150 miles from base.

However, von Pohl’s tenure as Fleet Commander was short-lived as he was terminally ill, dying of cancer, and he was replaced in January 1916 by Admiral Reinhard Scheer.

Reinhard Scheer had been born in 1863 in Obernkirchen, Lower Saxony, joining the Kaiserliche Marine at the age of 15 in 1879, serving in the Far East and on the East African Squadron from 1884 to 1890. After various commands, including the battleship SMS Elsass, Scheer was promoted in 1909 as Chief of Staff to the Commanding Officer of the High Seas Fleet.

In December 1913 Scheer was again promoted, this time to Vice-Admiral with the 2nd Battle Squadron, remaining in that position until January 1915.

After his eventual appointment to Fleet Commander, Scheer advocated for more aggressive tactics to be implemented, with a series of raids on the British coast to be undertaken, with the intention of drawing out isolated units of the Grand Fleet and luring them into a trap where they could be overwhelmed by a major portion of the High Seas Fleet lying in wait near the German coast.

By this method, together with the use of U-boats and raids by Zeppelins on the British mainland, Scheer intended to persuade Admiral Sir John Jellicoe to risk his precious ships in pursuing the German raiding squadrons deep into the German Bight.

A new offensive spirit now imbued the High Seas Fleet under its new commander and plans were made to employ Admiral Hipper’s fast battle-cruisers to draw part of the Grand Fleet into a trap at the first opportunity.

In Room 40 at the Admiralty in London, towards the end of January 1916 the increase in monitored wireless traffic indicated that some form of sortie was being planned by the German fleet.

On 9 February, the listening stations detected a peak in wireless communications at Wilhelmshaven and the Grand Fleet and the Harwich Flotilla were alerted for action. When it was revealed that a force of German light cruisers and torpedo boats had left the Jade Basin, the Grand Fleet, including the battle-cruiser force, put to sea at midnight on 10 February, heading south to join up with Tyrwhitt’s Harwich Force.

However, once again they were too late, as the German ships had fallen on a flotilla of minesweeping sloops off the Dogger Bank. After sinking one and inflicting damage on the others in an action lasting 35 minutes, they immediately ran for home, once again frustrating their would-be adversaries.

Although there appeared to be little to gain from Scheer’s minor sortie, it was all part of his plan to divide the British fleet, but Jellicoe was not to be moved, either by the German actions or demands from politicians at home, to base some of his battleships further south in the Humber and the Forth, thus splitting his force, a course of action which he firmly rejected.

Apart from the dreadful and seemingly unending carnage on the Western Front that was soon to climax in the Battle of the Somme that commenced in July, other troubles were at hand, with the outbreak in Ireland of the Easter rebellion in April led by Sinn Fein, providing a suitable diversion that Admiral Scheer felt he could take advantage of.

The British for their part were now convinced that such an action at sea might well take place, and accordingly the Harwich Force were recalled to harbour to prepare for action. Similarly, the battle squadrons at Scapa and the battle-cruiser force at Rosyth were coaled, stored and took on ammunition, and raised steam in readiness for action.

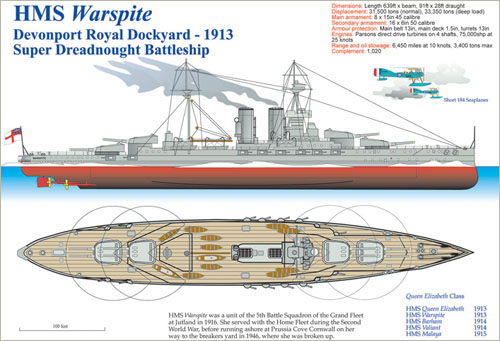

Again, the first indication of a suggested sortie came via the listening stations and on 24 April, while a fierce southerly gale beset Scapa, the Admiralty informed Jellicoe that conditions in the southern North Sea were more favourable and ordered the fleet to sea. This included the new powerful ships of the fast Queen Elizabeth 5th Battle Squadron.

At the same time Beatty’s battle-cruiser squadron departed Rosyth for the rendezvous point off the Dogger Bank.

The German fleet led by Admiral Bodicker, temporarily in command of the first Scouting Group, had sailed that evening, but had a mishap when SMS Seydlitz ran onto a mine off the Danish coast and was forced to return to Wilhelmshaven. The other ships of the scouting group pressed on westward, creating a very threatening situation, as the Grand Fleet were still too far to the north, and only Commodore Tyrwhitt’s Harwich Force stood between them and the vulnerable towns and harbours of the east coast.

In the first light of dawn, as Tyrwhitt’s cruisers sped north, they saw to eastward the unmistakable outline of three German battle-cruisers and accompanying warships on course for Lowestoft.

Completely outnumbered and outgunned, Tyrwhitt nevertheless closed on the enemy and, when sure that he had been seen, reversed course to the south to give time for Beatty’s battle-cruisers to come within range. Admiral Bodicker was not, however, deceived and held his course for Lowestoft, where he bombarded the town for 30 minutes with 12in shells before heading up the coast to Great Yarmouth, where he planned to mete out similar treatment.

Seeing this, the Harwich Force again reversed course to engage the German light cruisers at extreme range – an action which caused the battle-cruisers to abandon their attack on Great Yarmouth and pour heavy shell fire on the now retreating British ships, damaging the cruiser HMS Conquest and the destroyer Laertes, after which the enemy ships set off at high speed eastward for their home ports.

Tyrwhitt again turned his damaged ships to shadow the enemy and by 8.30 a.m. had their smoke in sight, but the British heavy ships were still too far away to bring the Germans to action and at 10.00 a.m. the chase was called off.

Dejectedly, as so often in the past, the British squadrons set course for their bases. Once again the Germans had escaped punishment while achieving a propaganda victory.

In Germany, the effect of the seeming ease with which ships of the High Seas Fleet could raid Britain’s coasts at will and escape pursuit and damage demonstrated the power of their fleet that could defy the Royal Navy with impunity. With this and other minor successes over the Royal Navy, the Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg called for the suspension of the policy of unrestricted submarine warfare that had caused a dangerous situation to develop between Germany and the United States.

Eventually, on 4 May, the policy was suspended and relations with the United States improved temporarily. Throughout May 1916 the commanders on both sides of the North Sea prepared their plans for what they now saw as an inevitable and imminent clash of arms.

Scheer was now aware that a new powerful force of fast capital ships, the 5th Battle Squadron, was now based in the Forth and he resolved to draw them out on their own by a bombardment of Sunderland, and to engage and overwhelm them quickly before the slower main units of the Grand Fleet could interfere.

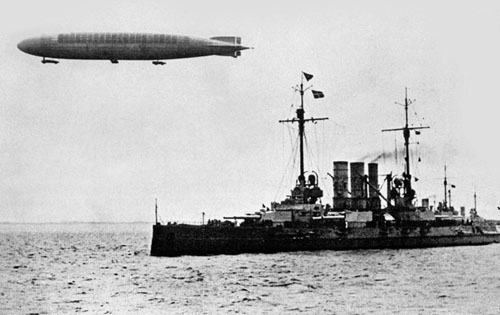

Additionally, and important to his plan, was the disposition of U-boats now released from commerce raiding to form a barrier along the lines of advance of the British fleet to attack them as they left harbour. He also planned to use Zeppelin airships to patrol ahead of the fleet to give an early warning of the approach of British ships.

As a result of the Lowestoft raid, and in response to public opinion but against the advice of Admiral Jellicoe, the First Lord of the Admiralty, Arthur Balfour, announced a redistribution of naval forces, with the 5th Battle Squadron being permanently based at Rosyth under the direct command of Admiral Beatty.

Admiral Scheer deployed fourteen U-boats to take up station off the British bases but they arrived too late, as Jellicoe’s ships had already passed through their patrol lines hours before.

Similarly, five Zeppelin airships were detailed on the morning of 31 May to patrol the North Sea to scout ahead of the High Seas Fleet as it made its way up the Jutland coast, followed by five other airships later in the evening, but in the event their reports were fragmentary and confusing and did little to help Admiral Scheer in understanding the movements of the British fleet during the Battle of Jutland. Although Admiral Beatty was later incorrectly convinced that the Zeppelin airships were the key that enabled Scheer’s ships to escape.

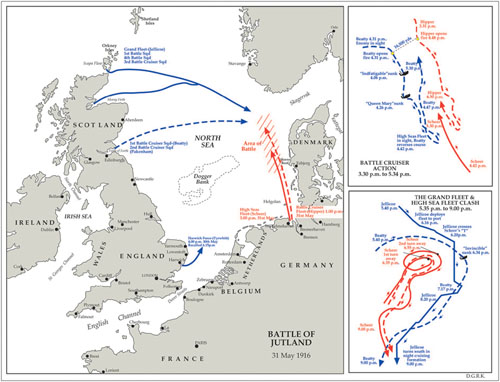

As both sides prepared their plans throughout May, increased wireless traffic alerted the Admiralty, and when, at 3.30 p.m. on 30 May, a signal originating from the German fleet flagship SMS Friedrich der Grosse had been decoded by Room 40 as ‘Carry out secret instruction 2940 on 31 May’, it was deduced that a major fleet operation was about to take place. In response Jellicoe ordered the entire Grand Fleet to sea.

Aboard the 148 ships at Scapa Flow, Rosyth and Invergordon, a scene of intense activity prevailed as the ships prepared for sea. All liberty men ashore were hastily recalled to their ships and with thick clouds of black smoke pouring from their funnels as they raised steam with all facility, each ship soon hoisting the signal to their yard arms, ready to proceed. By early evening the boom-defence trawlers had drawn back the anti-submarine nets and floating booms to allow the great ships through marked channels to the open sea.

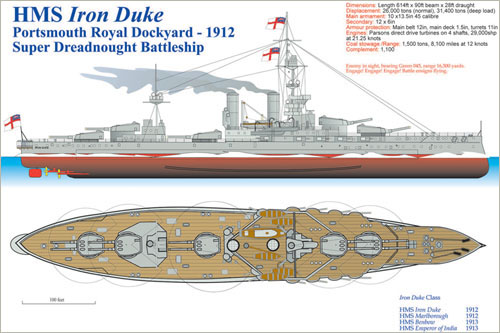

At 11.30 p.m. the flag signal ‘weigh anchor and point ship’ was run to the masthead of the fleet flagship Iron Duke and from Scapa, squadron by squadron, the ships of the Grand Fleet gathered way and slid out through Hoxa Sound, showing no lights, in ordered succession to their rendezvous eastward of the Long Forties. The King’s ships were at sea.

Jellicoe’s force consisted of twenty-four dreadnought battleships of the 4th and 1st Battle Squadrons (leaving from Scapa), the 2nd Battle Squadron (leaving from the Cromarty Firth), three battle-cruisers of the 3rd Battle-Cruiser Squadron, eight older armoured cruisers of the 1st and 2nd Cruiser Squadrons, together with eleven light cruisers and fifty-one destroyers.

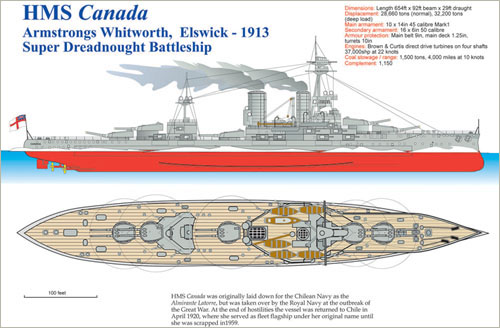

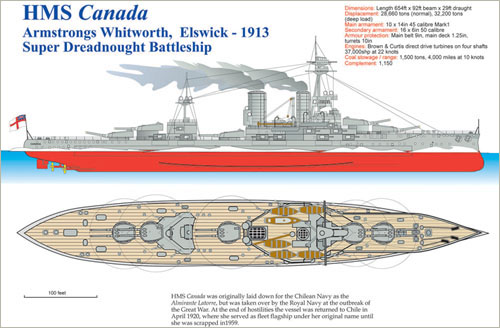

Similarly, at Rosyth Beatty’s flagship Lion at 11.00 p.m., the ships of the 1st Battle-Cruiser Squadron and four of the brand new 15in gunned Queen Elizabeth class super-dreadnoughts of the 5th Battle Squadron were lead out, a total force of four super-dreadnoughts, six battle-cruisers, one seaplane carrier, twelve light cruisers and twenty-nine destroyers. They set course direct for the Skagerrak at high speed, although the position of the German fleet was at that time still unknown to the British commanders. After joining forces with the 2nd Battle Squadron at 11.00 a.m. on 31 May, 200 miles east of the Cromarty Firth, Jellicoe continued east-south-east at a more leisurely pace towards the Jutland Bank until the German dispositions could be confirmed.

German Dreadnought SMS Ostfriesland with zeppelin L33 flying overhead. (Airship Heritage Trust)

The German forces were led by Admiral Hipper’s 1st Scouting Group of five battle-cruisers and four light cruisers of the 2nd Scouting Group, which left the Jade Basin at 1.00 a.m. on 31 May, 2 hours ahead of Admiral Scheer’s fleet of sixteen dreadnought battleships, a squadron of six pre-dreadnoughts, five light cruisers and four flotillas of torpedo boats that now followed them to spring the trap on Beatty’s ships, once Hipper’s battle-cruisers had drawn them in.

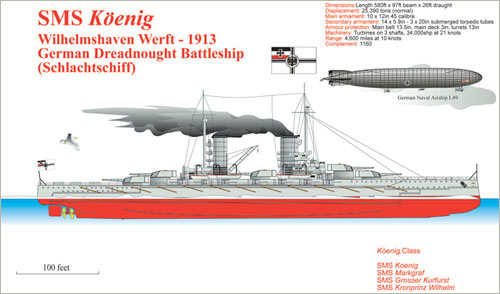

Typical of the German battleships facing Jellicoe was the SMS Konig, one of nine battleships comprising the 3rd Squadron of the High Seas Fleet.

The Germans had the advantage that their ships were designed to operate almost exclusively in the North Sea, whereas the British ships had to serve all over the world – a feature the Germans took full advantage of in their construction. Their systems of subdivision and damage control by flooding were superior to the British, as was their armour protection, which allowed their ships to take terrific punishment.

As mentioned earlier, cordite charges in the German ships were handled in brass canisters, and their system of magazine protection was clearly vastly superior to the British system, as demonstrated by the loss of three British battle-cruisers at Jutland.

German gunnery was also superior to the British. The accuracy of German opening salvoes was remarkable and the quality of the German shells was excellent, in contrast to the British, where often the faulty armour-piercing shells broke up on impact without penetrating the German armour. Without a doubt the German ships, class for class, were superior to the British.

The Konig had 25,390 tons’ displacement and was 580ft in length with a beam of 97ft. Her main armament consisted of ten 12in 45 calibre guns, with a secondary armament of fourteen 5.9in guns mounted in embrasures at upper-deck level turbines on three shafts of 34,000hp, which gave her a speed of 21 knots and a range of 4,600 miles at 10 knots. It carried a crew of 1,160.

The day broke clear and calm with only a gentle swell as Jellicoe’s battleships proceeded on a south-easterly course towards the rendezvous point in cruising formation of six columns of four ships in line abreast, steaming at 15 knots.

Visibility at that time of day was excellent, though it was to deteriorate later, while the cruiser screen, spread in a line 2 miles ahead of the fleet, anxiously scanned the clear horizon for the first signs of smoke that would indicate enemy ships.

After 7 hours of searching an empty sea, at 2.00 p.m., with Beatty’s battle-cruisers in the lead on a south-easterly course and with the 5th Battle Squadron following 5 miles astern of them, the two squadrons were approaching their turning point, from where they would reverse course to the north-east at what was seemingly the end of yet another fruitless search.

Unknown to Beatty, just beyond the horizon Hipper’s ships were steaming north-east, on a course that if nothing interfered would place them directly in the path of the British battle squadrons.

At 2.15 p.m., the signal to turn was given and Beatty’s ships began to swing round on to a north-easterly course.

As the turn commenced, the ships on the eastern side of the cruiser screen initially sighted the smoke and then the masts and upper works of a steamer to the east-south-east.

Commodore Alexander-Sinclair of the 1st Light Cruiser Squadron, flying his flag in HMS Galatea, turned towards the east to investigate the strange vessel, being followed in this change of course by the cruisers HMS Phaeton, HMS Inconstant and HMS Cordelia.

Simultaneously, 15 miles to the east on the west wing of the German scouting line, the cruiser Elbing had also sighted the steamer and, accompanied by two torpedo boats, turned to the west to investigate. The mystery vessel was the Danish steamer N.J. Fjord and, as the German and British ships closed on her, they each recognised the masts and funnels of enemy ships and flashed the flag and wireless signal ‘enemy in sight’ to their respective commanders. At 2.28 p.m. the Galatea opened up with her 6in guns at the Elbing, the first shots in the great sea battle.

The initial Morse wireless reports from both sides indicated the presence of only light units and, unknown to either Beatty or Hipper, the opposing battle-cruiser forces were at this time some 40 miles apart, heading towards each other at a combined closing speed of 45 knots.

In the initial exchange of gunfire the Galatea had been hit by a shell that had failed to explode, while Beatty, on receipt of a report ‘smoke to the south-east’, increased speed and turned onto that course, at the same time ordering the seaplane carrier HMS Engadine to launch a seaplane to scout ahead.

Due to the time it took to become airborne and the misty conditions now developing, the reconnaissance contributed no useful information to assist Beatty’s deliberations. A confused gun duel commenced, with either side struggling to discern what was the strength and class of ship ranged against them so that they could communicate the information to their respective commanders.

Beatty’s six battle-cruisers had now worked up to 25 knots, altered course and raced off to support the scouting cruisers, but Beatty’s flag signal instructing his squadron to go round to a south-easterly course could not be read by the Barham, the flagship of the trailing 5th Battle Squadron under Rear Admiral Evan-Thomas, it continued on its previous track for over 10 minutes before it altered course to follow the 1st Battle-Cruiser Squadron to the south-east. By then, however, due to its slower cruising speed, a gap of 10 miles now separated the two sections of Beatty’s command, which was to have repercussions later.

Pressing on regardless, Beatty led his six battle-cruisers towards the smoke on the horizon that presaged the advancing column of the German battle-cruisers, and at 3.30 p.m. the Lion, leading the line, had them in sight. Unknown to him, Admiral Hipper, in the recently commissioned SMS Lutzow, had spotted the British line 10 minutes earlier as he raced north at 24 knots. He immediately reversed course to the south in accordance with the plan to draw the British ships on to the main body of the High Seas Fleet hurrying north some 50 miles to the south.

Jellicoe and the Grand Fleet were in turn at this time around 60 miles to the north of Beatty’s ships and, having received partially incomplete reports as to the position of the German ships, were increasing speed as they pounded south to what they hoped would at last be a chance to bring the enemy under their guns. So began the first part of the battle, known to historians as The Run to the South.

Meanwhile, Beatty held his fire, being unable due to deteriorating visibility to accurately estimate the range. Hipper had no such problem, with the British ships starkly outlined against a westering sun, while they themselves were partially concealed by the mists to the east, and at 3.48 p.m. the German ships opened fire at 16,500yd.

Simultaneously, great tongues of flame leapt from the Lion’s fore turrets as her first salvo crashed out, but the range had been overestimated and the shells flew harmlessly over the German line to land almost a mile beyond them. The Germans on the other hand quickly found the range and after only a few salvoes the Lion, Tiger and Princess Royal had already been hit two or three times each.

The Princess Royal had her A turret put out of action and Tiger temporarily found her fore turrets jammed and unable to traverse, while her gun-laying director was badly damaged.

Jacky Fisher’s maxim of hit first, hit hard and keep hitting was patently not working for the British ships, and it was not until 3.55 p.m., with the range down to 12,800yd, that the first German ship to be hit was the Seydlitz. Two 13.5in shells from Princess Royal pierced a forward barbette and started a fierce cordite fire in the handling room below the turret, killing all the gun crew, which only by prompt flooding of the magazine saved the ship from a major disaster.

Once again, confusion with signalling resulted in two British ships firing on a single target leaving the Derfflinger to practise unhindered on the British line.

At 3.58 p.m. the Queen Mary, realising she was unengaged, shifted her fire to the Derfflinger, immediately scoring hits.

As both protagonists sped to the south-east with the range closing, both flagships were hit at the same time, and while the Lutzow’s damage was relatively minor, the Lion was almost lost when a 12in armour-piercing shell penetrated the midships Q turret, causing terrible carnage and sending a flash of flame through the open flash doors to the handling room, starting an intense cordite fire. The swift action of Major Harvey of the Royal Marines, who with his dying breath ordered the turret flooded, saved the ship. The order was carried out by Chief Gunner Warrant Officer Alfred Grant, who seized the red-hot flood-valve wheels, burning his hands terribly, to flood the chamber. Major Harvey was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross.

The German fire in contrast to the British efforts was extremely accurate, with Lion receiving six hits in rapid succession, while the Princess Royal had had Y turret aft disabled by a shell hit.

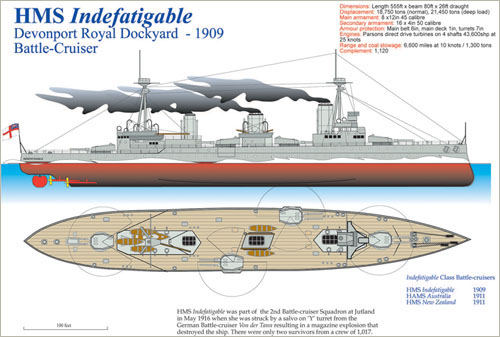

At 4.04 p.m. the rearmost ship Indefatigable, which had just started trading shots with the Von der Tann for 4 minutes, firing some forty shells without scoring a hit on the German ship, was hit herself with two 11in shells that struck together by the aft turret, penetrating the 3in armoured barbette. This caused a massive cordite fire that spread rapidly to the after magazine, exploding with great violence and blowing the bottom out of the ship. The ship began to sink rapidly by the stern, only to receive two further 12in shells on the A turret, which penetrated the forward magazine and caused a catastrophic explosion. The Indefatigable disappeared beneath the waves, and from her crew of 1,019 there were only two survivors.

The effect on the crews that witnessed the violent end of one of their much vaunted battle-cruisers must have been a profound shock, which together with the poor shooting of the British ships must have caused Beatty to question the wisdom of including these ships in the line of battle, for which they were not originally designed.

About this time, Lion, with damage-control crews struggling to control the fires raging on her, turned away from the German line, increasing the range to 21,000yd as Evan-Thomas’s 5th Battle Squadron eventually arrived on the scene, where, after sweeping the German light cruisers aside, at 4.08 p.m. at a range of 19,000yd brought a concentrated and accurate fire of fifteen salvoes to fall on the rear of the German line, with the Barham hitting the Von der Tann below the waterline and Moltke also receiving serious hits.With her fires partly under control, Beatty now turned back to close the range first to 16,000yd then to 14,000yd, with the Lion engaging Lutzow in a fierce exchange of fire. Despite the Lion being hit three more times, it seemed that at last severe punishment was now being meted out to the German line.

HMS Invincible battle-cruiser lost at Jutland, 1916. (Author’s collection)

It was now that a severe deficiency became apparent in the construction of the British projectiles. Despite the fact that British shells were falling accurately on their targets, they failed to penetrate the German armour, exploding prematurely and breaking up on impact, causing only minor damage. In the opinion of Admiral Hipper, this saved his ships from almost certain disaster at this stage of the battle.

At 4.17 p.m., the Derfflinger and Seydlitz shifted their fire to the Queen Mary, which had been making excellent practice on the German ships and which continued to respond with accurate fire, hitting both ships several times. At 4.26 p.m., to the horror of the observers on the Tiger and New Zealand next astern of her, three shells crashed home on the Queen Mary’s foredeck, followed by two further 12in shells from the next salvo. This caused a massive concussion as her magazines detonated in a colossal explosion that destroyed the forepart of the ship and flung a huge towering pillar of flame and writhing black smoke hundreds of feet into the air.

The Tiger, next astern, had to haul out of line to avoid hitting the wreckage, as debris from the doomed ship rained down on her decks. As New Zealand swept by she was shaken by further violent underwater detonations, as Queen Mary sank, taking 1,266 officers and men to the bottom of the North Sea.

As destroyers hurried to pick up the twenty or so survivors from the doomed ship, a shocked Admiral Beatty, contemplating the loss of two of his battle-cruisers within 22 minutes, was heard to remark on the bridge of the Lion to Captain Chatfield that, ‘There seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today’.

As the chase continued to the south-south-east, a fierce series of actions were being fought out between the British destroyers and the German torpedo boats, with HMS Obdurate and HMS Nomad being hit, while two German torpedo boats, V29 and V27, were sunk. The destroyers HMS Nestor and HMS Nicator launched torpedoes at the German battle-cruisers at 6,000yd which, although they missed, caused the German ships to turn away. Their own torpedo boats fired torpedoes at the British line from 9,000yd without effect.

Suddenly, the whole situation changed dramatically, as at 4.38 p.m. Admiral Goodenough’s 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron, scouting ahead, sighted from the Southampton the enemy battle fleet bearing 122° course 347° at a distance of 12 miles. Beatty waited until he saw the lead German battleship Konig emerging from the mist and, 7 minutes after the Queen Mary had been lost, at 4.33 p.m. he ordered his squadron to reverse course to the north-north-west, signalling the 5th Battle Squadron to follow suit. The battle now entered its second phase.

The German battle-cruisers had lured Beatty into their trap: the hunters had become the hunted.

The ships of the 5th Battle Squadron, Barham, Valiant, Warspite and Malaya, began their turn slightly later at 4.54 p.m., and were taken under fire from the High Seas Fleet at 19,000yd, with only Barham being hit, receiving only minor damage.

The destroyers HMS Petard and HMS Turbulent attacked the Seydlitz with torpedoes, striking her on the starboard side and causing damage and flooding in the forward boiler room, while the Marksman also fired torpedoes in pairs at the main German line without success. Later analysis showed that greater success could be achieved if attacks were made with groups of boats working together and launching multiple salvoes simultaneously.

The powerful Queen Elizabeths were now severely punishing the German battle-cruisers and at 4.55 p.m. both the already badly damaged Seydlitz and Derfflinger were hit by two 15in shells each.

Jellicoe and the battle squadrons of the Grand Fleet were now closing on the German fleet and had sent the 3rd Battle-Cruiser Squadron ahead to support Beatty’s depleted squadron. Under the command of Admiral the Honourable Horace Hood, the squadron at 4.00 p.m. increased speed to 24 knots and steered for the reported position of Beatty’s ships but, due to navigational errors, found the cruiser Chester on his starboard beam, which was being engaged by four German cruisers and had been hit seventeen times by 4.1in shells, receiving heavy damage and casualties, among whom was Boy First Class Jack Cornwall. He earned a posthumous Victoria Cross when, although mortally wounded, he remained at his gun awaiting orders when the rest of the crew were killed or wounded.

Admiral Hood’s squadron in turn now opened fire on the enemy cruisers from 10,000yd, their shells disabling SMS Wiesbaden and severely damaging SMS Pillau, while the light forces of both sides continued to launch torpedo attacks on their opposite numbers.

As Jellicoe pounded southward, he was frustrated by the lack of accurate information regarding the position of the main body of the German fleet, as Beatty had failed to keep him informed, and what signals he had received were contradictory and inaccurate, with only sketchy information as to the last known bearings, position and speed of the High Seas Fleet.

Beatty’s battle-cruisers were sighted at 6.00 p.m. where, with the onset of twilight, visibility had reduced to 7 miles and it was becoming imperative to have this information so that he could deploy the Grand Fleet from cruising formation of six lines of four ships in box formation into a single line 9 miles in length that would cross the enemy T, effectively trapping them.

At 6.01 p.m., Jellicoe signalled Lion ‘Where is the enemy’s battle fleet?’ After an interval of 14 minutes, due to poor communications the reply came from Beatty, ‘Have Enemy battle fleet in sight bearing south-west’.

This information arrived just in time, as the opposing fleets drew closer together and the flag signal ‘Equal Speed Charlie London’ broke from the masthead of the Iron Duke for the deployment of the port column of four ships, with the succeeding lines following in sequence, to form a single line on an east-south-easterly course. This manoeuvre was carried out not a moment too soon for, as the last of Jellicoe’s ships formed into line, the High Seas Fleet appeared out of the mist, heading straight for the British line.

This must have seemed a moment of triumph for Jellicoe. After 2½ years of frustration and disappointment, here at last the German fleet had sailed into his trap. For Admiral Scheer this must have been his worst nightmare. As he pressed on at full speed he found himself confronted by a continuous line of great grey battleships fading into the mist at either end, an iron trap from which only a miracle could save him and his fleet from complete destruction.

At the rear of the British line on deployment the Marlborough was nearest to the enemy and opened fire at 9,000yd range, and although visibility was poor she and the other ships of the 5th and 6th divisions poured a withering storm of shells into the van of Scheer’s battleships, wreaking terrible damage to the Konig, SMS Grosser Kurfurst, SMS Kronprinz and other ships of the 3rd Squadron of the High Seas Fleet.

At 6.20 p.m. the fleet flagship Iron Duke opened fire on a ship of the Kaiser class, scoring several hits and starting fierce fires.

The Iron Duke was a magnificent warship, 620ft in length, of 26,400 tons’ displacement. Her turbines developed 29,000hp to deliver 21 knots, she mounted ten 13.5in 45 calibre Mk V guns that could hurl a 1,400lb high explosive shell to a range of 25,000yd at an elevation of 20°. She was also extremely well protected with a 12in main belt and 1.5in armour to the main deck.

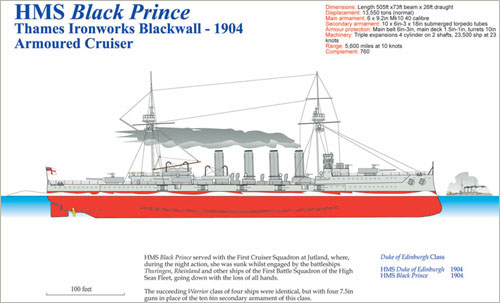

As the Grand Fleet deployed, the 1st Cruiser Squadron – comprising the armoured cruisers Defence, Warrior, Duke of Edinburgh and Black Prince – were led by Rear Admiral Sir Robert Arbuthnot towards the enemy line, suddenly they found themselves emerging from the mist to within 9,000yd of the German dreadnoughts. Immediately, a storm of shells fell on the ships, with a 12in shell piercing the Defence’s thin armour, penetrating her aft 9.2 magazine and, as explosions ripped through her, she blew up, completely disintegrating with the loss of all her crew and the Rear Admiral himself.

The Warrior was in turn struck by over twenty shells, but miraculously survived the onslaught, though in a sinking condition. She was saved from almost certain destruction by the Warspite which, suffering from a jammed helm, steamed out of line in two complete circles to within 10,000yd of the German line, diverting their attention from the Warrior. Warspite was hit over twelve times by heavy shells but was saved from serious damage by her effective armour.

The Warrior and the two remaining ships turned away to safety. The Warrior was taken in tow by the seaplane carrier Engadine but, despite their best efforts, she sank the next day 160 miles east of Aberdeen.

At 6.00 p.m., Beatty steered his ships across the front of the Grand Fleet, masking their targets with his smoke and delaying Jellicoe from closing on the German fleet. Likewise, Vice-Admiral Hood turned his three battle-cruisers to starboard and opened an accurate fire on the German battle-cruisers, with Invincible and Inflexible scoring eight shell hits on Hipper’s flagship Lutzow between 6.26 p.m. and 6.34 p.m., causing severe damage and flooding. Derfflinger received two hits from Indomitable while Seydlitz also took an armour-piercing shell.

As the duel continued, Lutzow and Derfflinger replied with accurate fire on HMS Invincible. At 6.34 p.m., a hit on the midships Q turret, penetrating the armour, started a fierce fire that quickly spread to the other magazines, and with a tremendous explosion the battle-cruiser blew apart, with the two halves sinking so that the bow and stern stood pointing to the sky like two steel tombstones. Of the crew of 1,028 there were only six survivors.

By 6.30 p.m., all the ships of the Grand Fleet were in action, pouring a continuous and rapid fire into the German line, with almost every ship being pounded mercilessly and tremendous damage being inflicted on them. If it were not for their exceptionally strong armour protection, watertight subdivision and superior methods of magazine protection to the British they would already have been sunk.

At this stage of the battle, despite the British losses, Jellicoe was in command and the German fleet were in danger of annihilation.

Hipper’s battle-cruisers were battered wrecks, with both Seydlitz and Defflinger having most of their guns knocked out, and both down by the bows with thousands of tons of seawater on board, while Lutzow was in a sinking condition and falling out of the line.

At 6.33 p.m., in a desperate measure to save his ships, Admiral Scheer ordered the Gefechtskehrtwendung, or battle turn away, to be implemented, where the German battleships all individually turned through 180° on to a reverse course. This manoeuvre was covered by a mass attack by the 3rd Torpedo Boat Flotilla, whose torpedoes, fired at great range, did no harm.

By 6.45 p.m., the German ships had vanished as though by magic into the mist to the south-east, where Jellicoe was unwilling to follow because of the threat of torpedoes and mines. Accordingly, he turned the fleet to the south by divisions en echelon to stand between the German line of retreat and their bases to the east.

At this stage, Jellicoe was unaware that Scheer had in fact reversed his course and initially assumed the disappearance of the enemy was due to deteriorating visibility to the west. He therefore continued his southern course for a further 10 minutes before he realised that the High Seas Fleet had in fact turned away from him. Admiral Scheer, on the other hand, was fully aware that the combined might of the Grand Fleet now stood between him and the safety of Wilhelmshaven harbour.

At 6.54 p.m. the Marlborough at the rear of the line was struck by a torpedo, possibly fired by the 5,200-ton light cruiser Wiesbaden that had earlier been disabled and left as a stationary target by Admiral Beatty’s battle-cruisers. She resolutely refused to sink, and continued to fire back at any ships that attacked her, despite being terribly damaged.

The Marlborough took on a 1,000 tons of seawater in her forward boiler room and developed a 7° list to starboard, but could still maintain its place in the line.

As the British ships began their cruise southward, the German fleet unexpectedly reappeared again at 7.00 p.m., once more on a north-easterly course.

Later, Admiral Scheer maintained that he had intended to re-engage Jellicoe’s fleet, but more likely it was an attempt to break through behind the British fleet and reach the safety of their harbours.

Once again Scheer found that Jellicoe had crossed his T. The battered High Seas Fleet was now in the utmost peril; his attempt to escape had led him on to the waiting guns of the Grand Fleet.

At 7.00 p.m., with visibility favouring the British, while the Germans were starkly outlined against the setting sun, the Ajax opened fire from 18,000yd, followed by the other battleships, which smothered the van of the advancing German ships with a storm of shell-fire, causing them to suffer further heavy damage.

Scheer, alert to the possibility of the complete annihilation of his command, ordered his severely damaged battle-cruisers – now under the command of Captain Hartog of the Derfflinger, as the Lutzow had fallen out of the line in a sinking condition – to charge the British line and cover the withdrawal of the fleet.

The four battered battle-cruisers approached to within 7,800yd of the British battleships, where they received fearful punishment.

The Derfflinger was hit at 7.14 p.m. by a 15in HE shell from HMS Revenge, which penetrated the aftermost Y turret and exploded under the turret, killing the crew and starting a fierce cordite fire, which, thanks to good magazine protection, was contained.

A further hit from Revenge 3 minutes later penetrated the barbette of the aft X turret, starting another serious cordite fire, which also was brought under control.

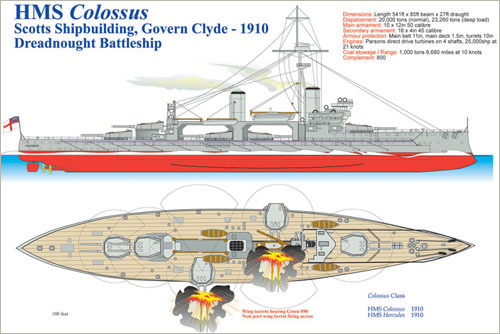

Revenge scored two further hits on the boat deck and over the next 8 minutes Derfflinger took five 12in shells from HMS Colossus and one 12in HE from HMS Collingwood, with this shell exploding in the sick bay, wrecking a greater part of the superstructure.

Three further 15in shells from Royal Oak and a 12in shell from HMS Bellerophon also smashed into her around 7.20 p.m.

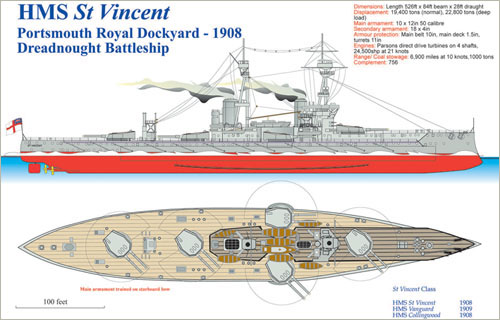

The Seydlitz received five hits between 7.14 p.m. and 7.20 p.m.: four 12in from HMS Hercules and HMS St Vincent and a 15in shell from the Royal Oak, these shells wrecking the aft superfiring turret and the 15in shell disabling the starboard 11in turret. At the back of the line Von der Tann and Moltke were hit several times. Finally, the battered hulks turned away, following the fleet into the smokescreens to the south. The death ride of the German battle-cruisers was at an end.

While this action was taking place, Scheer’s battleships continued to take severe punishment, with the Konig being hit and the Grosser Kurfurst being hit seven times by 15in and 13.5in heavy shells from the ships of the 5th Battle Squadron, while the mighty Agincourt with her fourteen 12in guns hit SMS Markgraf and Kaiser with two shells each. SMS Helgoland received a 15in round that broke up on impact, causing only splinter damage.

At 7.18 p.m., Scheer ordered the second battle turn away, with his torpedo-boat flotillas covering the change of course with smokescreens and attacking the Grand Fleet. Jellicoe ordered the 4th Light Cruiser Squadron and destroyer flotillas to counter the move.

The German torpedo boats approached to within 7,500yd before discharging their torpedoes, where they were engaged by the battleships’ secondary armament. The German torpedo boat S35 was sunk by gunfire and others damaged. In all, about twenty-one torpedoes were fired, causing Jellicoe to order his ships to turn away to comb the tracks.

At this stage of the battle the German fleet were tactically beaten and there can be little doubt that, had Jellicoe turned towards instead of away from the German fleet, once contact had been re-established in the twilight, the ensuing action would have resulted in the annihilation of the High Seas Fleet. By turning away with half an hour of daylight left, the two fleets were moving away from each other at 20 knots.

At the same time Jellicoe was poorly served by his scouting cruisers, who failed to keep him informed of the enemy’s movements. Equally, his subordinate captains in the line showed a lack of initiative when those at the rear of the line, who had clearly seen the German fleet reverse course, failed to inform their Commander-in-Chief of this vital information.

Even Goodenough’s cruiser squadron, that up to now had been the most reliable source of information communicated to Jellicoe, saw at 7.30 p.m. the German battle fleet turning away to the south-west, but failed to communicate this urgent news to Jellicoe. At last realising that the German ships were on an opposing course at 7.35 p.m., Jellicoe turned to starboard in pursuit of the High Seas Fleet, expecting to come up with them again at 8.00 p.m., while at 7.45 p.m. Beatty’s battle-cruisers, heading south-west across the path of the Grand Fleet, pressed on attracted by the sound of gunfire to the south.

Beatty regained contact with the German Fleet, which he duly reported to Jellicoe, but only supplied the bearing, again without indicating the ships’ heading.

Beatty once again fell on the four German battle-cruisers, causing more terrible damage to them. Derfflinger had lost six of her eight 12in guns, while Seydlitz and Von der Tann had four each out of action. Only Moltke had all ten of her guns fully operational.

Princess Royal opened fire at 8.19 p.m. at 12,000yd, scoring two hits with 13.5in armour-piercing shells, while Lion scored a hit on Derfflinger that jammed her sole remaining turret. At the same time she received three well-aimed shells from the New Zealand that, striking forward, burst under her armoured deck and increased the rate of flooding. The German ships attempted to make a reply but made no heavy-calibre hits, although Lion was hit by a 5.9in shell.

To the west of the German line, Beatty spotted the pre-dreadnoughts of the Second Squadron, the Princess Royal hitting SMS Hannover and Tiger straddling Hessen, while New Zealand hit SMS Schleswig-Holstein with two shells and fired on SMS Schlesien.

In turn, the Indomitable hit SMS Pommern with a 12in shell but was forced to cease fire at 8.33 p.m., as with the onset of darkness her gunlayers were unable to observe the fall of shot.

The British ships drew off and the action ended at 8.40 p.m. Five minutes later German battleships were spotted by the cruisers HMS Royalist and HMS Caroline of the 4th Light Cruiser Squadron, which moved to make an attack, but their commander, worried they might be British, stopped them. Eventually, however, he was persuaded to the contrary and the cruisers pressed home an attack, with torpedoes fired at a range of 7,000yd – all of which missed.

By now, at 9.15 p.m., it was too dark to consider further fleet action and at 9.17 p.m. Admiral Jellicoe ordered the fleet to assume night cruising order, with the intention of keeping between Scheer and his base and to renew action at first light. Admiral Beatty at the same time was positioned some 10 miles to the west of the battle fleet heading south-south-east, and took no further part in the night action.

On the German side at this time Admiral Hipper had transferred from the sinking Lutzow to the relatively undamaged Moltke, while Admiral Scheer in turn ordered his fleet to form line with the Westfalen at the head of the 1st Squadron and set course for Horns Reef.

The two fleets were now both steering SSE on gradually converging courses, although the slower cruising speed of the German fleet dictated that it would pass astern of the battle squadrons of the British fleet in the dark of the night.

The first skirmishes between the scouting flotillas began at 10.00 p.m. when Scheer’s 7th Scouting Flotilla encountered the British 4th Flotilla stationed astern of the Grand Fleet.

The German torpedo boats S14, S16, S18, and S24 launched torpedoes, to which the destroyers HMS Garland, Constant and Fortune replied with gunfire.

At 10.24 p.m. the light cruiser Castor, leading the 11th Flotilla, fought an action with the German light cruisers SMS Hamburg, Elbing and Rostock, with Castor hitting Hamburg with three 6in shells and who in turn was hit by ten 4.1in shells, which failed to penetrate the cruiser’s armour.

Fifteen minutes later the German ships were joined by their 4th Scouting Group that included the light cruisers Stettin, Frauenlob and Munchen, which engaged Goodenough’s 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron in a wild melee illuminated by searchlights, gun flashes and burning ships.

Stettin fired ninety-two 4.1in rounds at Southampton, knocking out a 6in gun, wrecking her wireless and causing many casualties.

Southampton responded by putting a torpedo into SMS Frauenlob and fatally damaging her with gunfire. She was set ablaze and capsized, with only nine survivors being picked up.

At 11.00 p.m., the Grand Fleet had unknowingly pulled ahead of the High Seas Fleet and Scheer altered course to port to break through the rear of the British line. The British destroyer flotillas began a series of confused actions, demonstrating the weakness in their training, and as a result these attacks were made piecemeal and in an uncoordinated manner, making them ineffectual.

At 11.30 p.m., the 4th Flotilla ran into the High Seas Fleet crossing its path. A challenge from Tipperary was answered with a blast of fire from the 5.9in guns of the Westfalen, followed by the Nassau opening up on the other destroyers.

The British ships fired torpedoes and, as the battleships turned away to avoid them, the battleship Posen rammed the cruiser Elbing, which later sank.

The Spitfire, after firing her torpedoes, rammed the Nassau, carrying off a section of the battleship’s armour, and survived this close encounter to return to the Tyne next day.

As the Broke led the 4th Flotilla, she spotted the cruiser Rostock, torpedoing her in her boiler room. She was brought to a halt and later sank. The Broke was heavily damaged by the Rostock’s 5.9in guns and the destroyer Conquest ran into Sparrowhawk, which was abandoned in a sinking condition.

Fortune was set on fire by Westfalen, while Ardent in a final brave attack at 12.25 a.m. on Westfalen was pounded into a blazing wreck and sank together with the badly damaged Tipperary.

The final loss of a major British heavy unit occurred at 10 minutes past midnight, when the armoured cruiser Black Prince, that earlier had been in action with the 1st Cruiser Squadron when the Defence had been blown up and the Warrior disabled, had for some reason been left behind by the fleet.

Now to the south-west, Captain Bonham closed on to a line of ships he assumed were British, when at 3,000yd range a German recognition signal flashed out in the darkness. Captain Bonham hauled round to port in an attempt to escape, but his fate was sealed.

Illuminating the Black Prince with searchlights, the Thuringen raked the cruiser with a storm of shells and she soon was ablaze from stem to stern.

As each succeeding ship swept past the wreck, they also added their quota of fire, leaving the Black Prince a blazing wreck, although she bravely attempted to fight back, hitting the Rheinland with two 6in shells. Eventually her magazines blew up in a colossal explosion and she vanished with all hands.

By an hour after midnight the German battle fleet had already broken through the destroyer screens and were crossing behind the Grand Fleet, while the sounds of firing and explosions were lighting the sky to the north of the British battle squadrons. As they headed south, they failed to inform their Commander-in-Chief aboard the Iron Duke of these startling developments, and minute by minute the opportunity to achieve what would have been the most comprehensive naval victory of all time slipped through his hands and evaporated with each mile further south that Jellicoe’s ships sailed.

With the first streaks of dawn lighting the eastern sky at 2.10 a.m., the ships of the German Second Squadron broke through a final attack by the 11th Destroyer Flotilla, which delivered the heaviest combined torpedo attack on them, firing ten or so at a range of less than a mile, one of which struck the pre-dreadnought Pommern. This resulted in several internal explosions, followed by a tremendous explosion that blew the ship in two, after which it sank with all hands.

Earlier at 1.00 p.m., 90 miles off the Lyngwig lighthouse on the Danish coast, the foundering Lutzow lost its fight to stay afloat and her crew were taken off by torpedo boats as she sank bow first, with her screws lifting out of the water as she went down.

The Seydlitz was also struggling to keep afloat, having received one torpedo hit and twenty-one heavy and two medium-calibre shells. As dawn broke she was aground on a shoal off the Horns Reef with ninety-eight of her crew dead and fifty-five wounded, while Derfflinger, her decks a mass of twisted wreckage with 157 dead and twenty-one wounded, accompanied by the battered Moltke and the Von der Tann, crept eastwards into the dawn and slowly one by one the remnants of the High Seas Fleet returned to harbour.

Seydlitz was freed by the tugs sent to help her and, with pumps working at full pressure, she was towed off and stern first brought eventually safely into Wilhelmshaven on 2 June.

At 2.30 a.m., as the sky lightened into dawn, Admiral Jellicoe searched to the north-west for the expected signs of the High Seas Fleet, but to his great disappointment the horizon was empty. Beatty’s battle-cruisers and the 5th Battle Squadron were out of sight some 16 miles to the south-west while his destroyer and cruiser flotillas were scattered far and wide.

Marlborough, having been hit by a torpedo, was being towed by the cruiser Fearless to the Humber, arriving on 2 June with her bows almost awash, but was repaired, rejoining the Fleet in September.

The Warspite was another casualty and, although extensively damaged in the battle, made her way back across the North Sea to Rosyth, being attacked by a U-boat on the way which she attempted to ram. After repair, she rejoined the fleet in July.

At 3.00 a.m., fearing that the German fleet had passed astern of him in the night, Jellicoe ordered a reversal of course to the north to try to regain contact with the High Seas Fleet and bring them under his guns once more, but he was too late.

Then at 3.55 a.m., Jellicoe received a wireless signal from the Admiralty informing him that at 2.30 a.m. the High Seas Fleet were in a position 16 nautical miles west of the Horns Reef, steering south-east at 16 knots.

This news came as a terrible shock to the Commander-in-Chief, as he realised that his chance to destroy the German fleet had been lost. Jellicoe turned his fleet for home at 7.30 p.m., collecting stragglers as they made their way across the North Sea. The great sea battle was over.

The Germans had suffered considerable material damage to their fleet, but perhaps the greatest damage was to the morale of the officers and sailors of the German fleet. The battering they had received at Jutland left them with little appetite to meet the Grand Fleet again at sea.

On the German side they had lost 2,115 crewmen, the battleship Pommern, the battle-cruiser Lutzow, light cruisers Elbing, Wiesbaden, Rostock and Frauenlob, together with the torpedo boats V4, V27, V29, S35 and V28.

British losses were altogether heavier, with 6,095 officers and men killed and the loss of three battle-cruisers – Invincible, Indefatigable and Queen Mary – together with three armoured cruisers – Defence, Warrior and Black Prince. Destroyer losses were Tipperary, Ardent, Fortune, Nestor, Nomad, HMS Shark, Sparrowhawk and Turbulent.

On balance it could be construed that, as the Germans claimed on reaching port before the British, that they had won a famous victory and this is how it appeared to the neutral nations. But the Grand Fleet had come within an ace of annihilating the High Seas Fleet, a fact that Admiral Scheer was only too conscious of, knowing that luck had been his greatest ally on that fateful day and that the Royal Navy still had command of the seas.

The day after the battle, Admiral Jellicoe could report that the Grand Fleet was ready for sea in 24 hours, as opposed to the several months required for the High Seas Fleet to repair their damage.

To say the British were disappointed with the results would be an understatement, and most of the odium for failing to destroy the German fleet fell on Jellicoe. By November 1916 he had been removed from command of the Grand Fleet and in a sideways promotion was appointed as First Sea Lord, while command of the fleet went to the more popular commander, at least in the public’s opinion, the dashing Sir David Beatty.