The Royal Navy in the shape of the Royal Naval Air Service had shown a great deal of interest in hydro-aviation before the outbreak of the war, actively fostering the development of seaplanes and flying boats, as this form of flying machine was seen as particularly suited to naval purposes.

The navy’s approach to the acquisition of aircraft was to obtain them from diverse sources, in contrast to the army’s almost sole reliance on the products of the Royal Aircraft Factory.

Short Brothers, in particular, and other private firms were encouraged in the development of seaplanes for naval use, with the navy trying out a wide variety of aircraft from the various manufacturers to determine those types most suitable for the particular demands of service at sea.

Early in 1908, in response to the success of the Zeppelin Company in Germany, the British Government in the form of the Committee of Imperial Defence – with the enthusiastic backing of both Prime Minister Asquith and the wily First Sea Lord Admiral Fisher – evaluated the threat posed by the advent of aerial navigation in time of war to Great Britain. They also considered what use aerial craft could be put to in the defence and came to the conclusion that a large rigid framed airship similar to a Zeppelin would be an indispensable asset to the Royal Navy in a scouting capacity.

At the time, the Admiralty was ahead of the Imperial German Navy in adopting the concept of the scouting airship working with the fleet; although it was widely believed in official circles that the German Navy were already building such craft.

In July 1908, Messrs Vickers Son & Maxim were given a contract to build what was described in the specification as an aerial scout, capable of 40 knots for 24 hours and able to rise to an altitude of 1,500ft, carrying wireless and other naval equipment. It had a crew of twenty officers and men, with a projected gross lift of 20 tons and a disposable (useful) lift of 3 tons. Such a vessel would be required to keep station with or scout ahead of the battle fleet, forming an extended patrol line to report the presence of enemy warships.

Built under conditions of the greatest secrecy, the airship R1, or Mayfly as she became known, was built at Barrow in Furness in a shed built out over the Cavendish dock, eventually emerging in May 1911 to be moored to a mast, where, floating on the water, she remained for three days riding out a storm. The finished vessel was 512ft in length with a beam of 48ft, but was adjudged to be too heavy and unable to fly.

On being returned to her shed, action was taken to lighten the ship by removing the equipment and the keel walkway structure but, as the airship was being taken out for further testing, a squall caused her to be crushed against the shed structure and she became a total loss, causing the Admiralty to temporarily abandon airship construction.

The first occasion on which an aircraft was to fly from the deck of a warship took place as early as November 1910 when a US Navy Curtis biplane was launched from a platform built over the forward 5in gun of the cruiser USS Birmingham in Hampton Roads.

Later, this feat was emulated by the Royal Navy when the dashing Lieutenant C.R. Samson flew a Short S27 off the foredeck of the battleship HMS Africa, moored in the Medway in December 1911. Later in May of the following year, he repeated the feat from a staging fixed over the bows of the battleship HMS Hibernia as the ship steamed at 15 knots in the English Channel.

The Royal Navy took the lead in the development of specialised ships for the carrying and launching of aircraft when, in early 1913, the old 5,500-ton cruiser HMS Hermes was converted to carry two seaplanes from a platform fitted forward. A rather precarious method of launching was accomplished by mounting the seaplane on a wheeled trolley, which was guided by rails during take-off to be jettisoned into the sea, with the aircraft being recovered from the sea by crane upon its return.

It is difficult for us today to realise just how revolutionary and extraordinary these developments appeared to be in 1910, when the aeroplane had literally only just emerged as a practical proposition and capable of being effectively controlled in the air.

After conducting trials, the Hermes was converted back to a cruiser, only to be reconverted to a seaplane carrier at the outbreak of war, where unfortunately she was torpedoed by the U27 on 31 October off Dunkirk.

It says much for what was often considered to be a hidebound and inflexible organisation that the British Admiralty demonstrated considerable foresight in condoning these experiments at such an early date. Encouraged by these experiments, a collier was converted while building in 1914 to become the first purpose built seaplane carrier.

This ship, bearing the illustrious name Ark Royal, carried its aircraft in her holds, from where they were craned out for launching either from the short flying-off deck at the bows or by being lowered into the water when the ship was stationary for take-off and recovery. Ark Royal was 330ft in length with a beam of 50ft and powered by a 3,000hp vertical triple expansion engine that gave a speed of 11 knots. Her armament consisted of four 12pdr guns and accommodated eight seaplanes in her hold.

After the war she continued in a training role, being renamed Pegasus in 1934, and served through the Second World War as an aircraft transport and experimental catapult ship, finally going to the breakers in 1950.

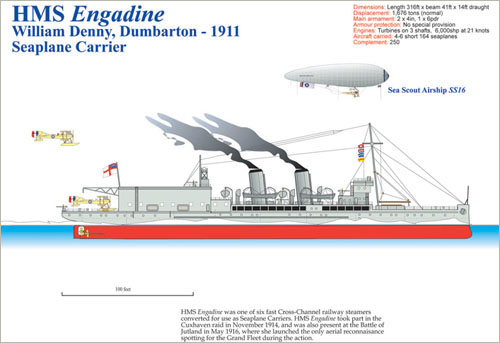

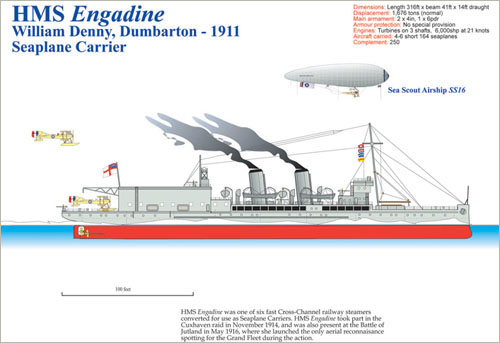

Similar arrangements for the accommodation of aircraft and launching methods were employed in the second generation of carriers that were the faster Isle of Man steam packets and railway cross-Channel steamers, which had been impressed into service in 1914. These handy ships gave excellent service – their relatively high speed enabling them to keep station with the fleet – with the Engadine taking part in the Cuxhaven raid of December 1914, where her aircraft reconnoitred the German anchorages.

Later, at the Battle of Jutland the same ship, while attached to the battle-cruiser squadron, sent up an aeroplane that spotted the German High Seas Fleet – this being the only aircraft (as opposed to airship) reconnaissance made by either side during the engagement.

The Engadine was of 1,676 tons’ displacement, 316ft in length, with a beam of 41ft. Her steam turbines were of 6,000hp, giving 21 knots, and her six Short 186 seaplanes, whose wings folded flat along the fuselage, were stored in a large hangar at the stern of the ship. At Jutland she also took in the heavily damaged armoured cruiser Warrior, which had to be abandoned the next day in a sinking condition.

After the war she was sold back to the South Eastern and Chatham Railway and later sold on to a US shipping company. She ended her days being mined off Corregidor in December 1941, with a large group of refugees aboard fleeing Japanese invasion of the Philippines.

Other actions involving these plucky railway ships included the Isle of Man steam packet Ben-My-Chree which, while in service during the Dardanelles campaign, launched the first successful air torpedo attack on a ship, before later being sunk by Turkish shore batteries.

The old Cunard record breaker HMS Campania of 20,000 tons built in 1893 was 622ft in length on a beam of 65ft, while her old engines of 28,000hp could still provide a speed of 19 knots.

She had been bought from the ship breakers at a nominal sum and converted in 1914–15 to carry ten aeroplanes. A 160-ft sloping flying-off deck was installed from her bow to her bridge. The forward funnel was split into two and the runway passed between them.

She was stationed with the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow and often accompanied the fleet on sweeps of the North Sea, launching aircraft in favourable conditions on reconnaissance duties; although it was not until June 1916 that the first Short 184 torpedo bomber took off from her deck.

Campania was absent from Jutland due to an oversight when she did not receive the order to put to sea at her remote location in the anchorage. Thus, her aircraft were unavailable to Jellicoe at a critical time when their observations could have had a positive tactical influence on the outcome of the battle.

Between 1914 and 1917, other fast cross-Channel railway steamers, including the HMS Empress, HMS Riviera, HMS Manxman, Pegasus, and HMS Narnia, were added to the increasing number of ships that could launch aeroplanes.

Although the Royal Navy pioneered the development of the aircraft carrier in these early days, the main function of their aircraft was seen primarily to be in the role of a scouting adjunct to the battle fleet, with their offensive capability being regarded as a secondary consideration.

During the inter-war years this philosophy was maintained and, while torpedo-carrying aircraft were a part of the carrier’s complement, the primary duty of the fleet’s aircraft continued to be in the area of reconnaissance.

The United States and Japan, on the other hand, recognised and developed the offensive potential of carrier-borne aircraft that could strike at a distance far beyond the range of the guns of battleships. Extending this philosophy, some American and Japanese naval planners even foresaw the day when carrier-borne aircraft would launch massive attacks on an enemy fleet, while the opposing fleets were hundreds of miles apart, and could even deal a decisive blow without the fleets ever meeting.

In pursuit of these revolutionary ideas both the Americans and Japanese began building large fleet carriers, equipped with large squadrons of dive bombers, and torpedo-carrying planes to be used as long-range artillery; in both navies this policy was pursued with determination and employed with devastating effect during the Second World War.

The Royal Naval Air Service was particularly active in the early stages of the war in countering the Zeppelin threat, such as the incident in the early morning of 7 June 1915 when Flight Lieutenant R.A.W. Warneford, flying a Morane scout armed with six 20lb bombs, took off from Dunkirk to intercept the Zeppelin LZ37 returning from a raid on England over Ghent. He destroyed her by dropping a string of bombs along her back, causing her to explode with great violence, falling on a convent in the suburbs of Ghent.

On the same morning fellow pilots, Flight Lieutenants Wilson and Mills flying Henri Farman bombers, attacked the Zeppelin sheds at Evere, near Brussels where the returning Zeppelin LZ38 had just been berthed after the raid.

On 9 October 1914, the Dunkirk squadron had earlier scored a success when Commander Spencer Grey and Flight Lieutenant Marix, flying Sopwith Tabloid biplanes, bombed the sheds at Dusseldorf, destroying the army Zeppelin Z9 laying inside – the first success of its kind for the RNAS.

A further setback to German plans was dealt by a third and even more daring raid carried out from Belfort near the Alsace French border that was aimed at the very heart of the Zeppelin empire at Friedrichshafen. On the morning of 21 November 1914, three Avro 504s, each carrying four 25lb bombs, flew 125 miles through the mountains on a route designed to avoid Swiss territory. They emerged at sea level on the south side of Lake Constance, before climbing to attack the Zeppelin works, where the British airmen hit their target, damaging a Zeppelin under construction.

The serious threat posed to British merchant shipping by the depredations of German undersea craft operating along the North Sea coasts and the English Channel resulted not only in the loss of numerous merchant vessels, but the Royal Navy during the course of the war lost twelve capital ships and numerous smaller craft to mines and torpedoes. This encouraged the Admiralty to seek a remedy in the use of the aeroplane and the airship for mine-spotting and anti-submarine duties.

As a result of these alarming developments, an urgent conference was called at the Admiralty in February 1915, presided over by Lord Fisher, to address the problem and find an immediate solution to the submarine menace.

Following their Lordships’ deliberations, proposals were made for the provision of faster CMBs and other patrol craft armed with depth charges and strengthening the light cruiser and destroyer flotillas based in the Channel and on the east coast, aided by patrols of seaplanes in coastal areas.

Lord Fisher also summoned Wing Commander Masterman and Commander Neville Usborne, two experts in the operation of airships, to the Admiralty to evaluate the possibilities of using small airships as submarine hunters and spotters to cooperate with the surface warships.

After receiving an assessment of the practicality of using such craft from the two officers, Fisher issued instructions for the immediate production of a number of small, fairly fast airships that could be handled after a minimum of instruction by a midshipman and two ratings, as well as being used for the purpose of hunting down and destroying enemy submarines within coastal waters.

It says much for Fisher’s determination and organising ability that, within the space of three weeks of receiving the order, the first three SS or Sea Scout airships were ready for their trial flights.

Of the forty-nine Sea Scout airships built, the majority had long service lives working between 2 or even 3 years while operating under the most arduous conditions – proof of the rugged construction of the type. They were very successful within their limitations of performance, flying on average for over 1,000 hours and covering thousands of miles on vital convoy, patrol and mine-spotting work.

Later models with extended range included the larger Coastal and North Sea classes that could remain on continuous patrol for over 50 hours, the record being set by the North Seas airship NS11, which in July 1919 made a continuous cruise of 101 hours, traversing 4,000 miles on mine patrol.

During the latter stages of the war, July 1917 to October 1918, RNAS airships flew in excess of 1,500,000 miles, escorted 2,200 convoys, flew 10,000 patrols, sighted fifty U-boats, attacking twenty-seven (the majority in concert with surface craft), and sighted 200 mines, destroying seventy-five from the air.

When favourable weather conditions allowed airships to operate with the fleet on their forays into the North Sea, they greatly extended the scouting line of the fleet’s cruisers. Although by late 1917 the navy were coming to rely increasingly on the use of the first generation aircraft carriers or aircraft carried by cruisers and battleships for this form of reconnaissance.

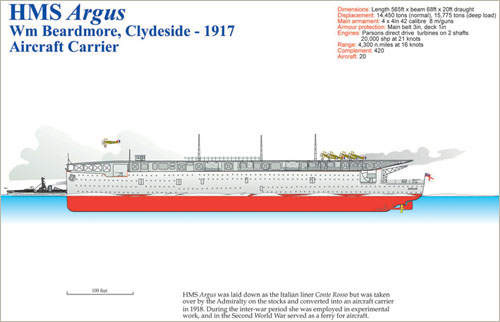

By 1918 the earlier aircraft carriers had been joined by HMS Argus, the first flush-decked carrier, formerly an Italian liner, that had been appropriated by the Admiralty. It was equipped to carry twenty aircraft, which in design foreshadowed the Woolworth cargo ship conversions to light aircraft carriers of the Second World War.

Argus was of 14,450 tons’ displacement, with an overall length of 565ft and a beam of 68ft. Her 20,000hp Parsons steam turbine on four shafts gave a top speed of 20 knots. She carried a crew of 495 and a complement of fifteen to twenty aircraft over a range of 6,500 miles. Being completely flush-decked without any superstructure or funnels, the smoke from the furnaces was ducted through vents on the sides aft in an effort to reduce the air disturbance over the deck to aircraft landing on.

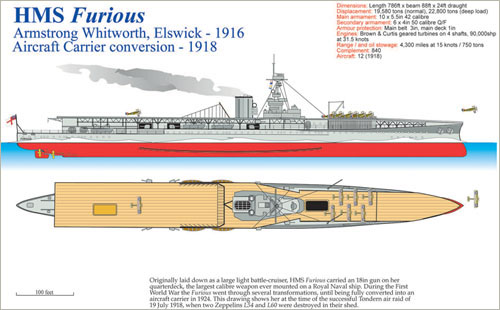

Argus was joined by the massive HMS Furious in 1918, a converted large light battle-cruiser and equipped with a complement of twenty planes. Furious was of 19,500 tons’ displacement and 786ft in length with a beam of 88ft. Her Brown & Curtis geared turbines of 90,000hp gave a speed of 31.5 knots.

Two sister cruisers, the Glorious and Courageous, were similarly converted to aircraft carriers after the war. These three ships had originally been designed to support a landing on the coast of Germany, being heavily armed with 15in guns and of shallow draught in order to operate in the waters off the Frisian Islands. Fortunately for all concerned the plan was not proceeded with.

Completed as an aircraft carrier, in her initial conversion Furious still sported her funnel and bridge superstructure on the centre line of the vessel, with separate landing-on and flying-off decks fore and aft connected by runways either side of the bridge structure to allow for transfer of aircraft between the decks. The aircraft were stored in holds fore and aft from where they were craned on to the deck for take-off.

On 19 July 1918 the Furious took part in the successful Tondern air raid, the first ever carrier strike from the sea on a land target, where two of the latest model Zeppelins, L54 and L60, were destroyed.

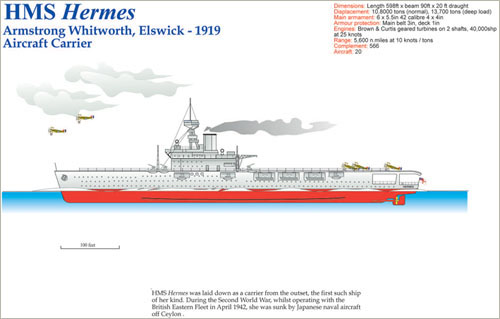

The first ship to be designed as an aircraft carrier from the keel up was Hermes of 10,800 tons. It was launched in 1919 but not completed until 1923, equipped to carry twenty aircraft and the first to establish the now accepted design feature of setting the funnels and superstructure out on the starboard side to allow for a continuous, unobstructed flying-off deck.

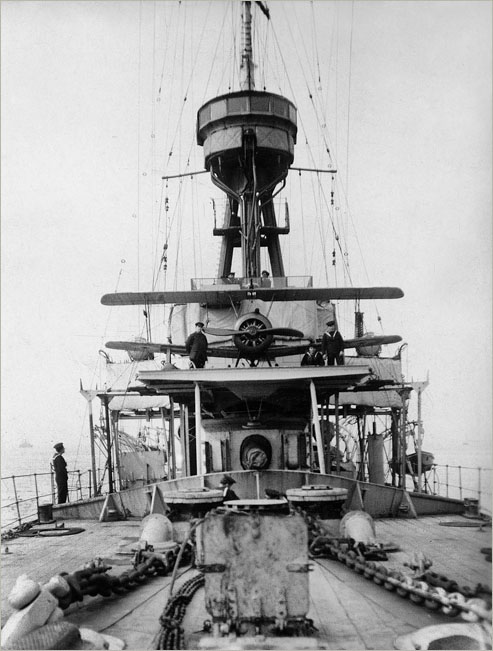

The provision of aircraft for use by the fleet grew rapidly as the war progressed, so that by November 1918 the navy possessed over 130 aircraft operating at sea and were further supported by 104 patrol airships. In addition, many of the battleships were by that date fitted to carry a two-seat reconnaissance biplane over the forward gun turret, while twenty-two of the light cruisers were similarly equipped.

An advantage of this method of launching aircraft was that the turret could be turned into the wind, while the ship itself could maintain her course without the need to turn aside to face into the wind.

The Royal Naval Air Service were also very active in the Mediterranean theatre throughout the war, being involved at the outset with the Dardanelles campaign, where RNAS aircraft spotted for the guns of the battleships and located the mine barrages. They operated off the Syrian coast, the Gulf of Aqaba and the Red Sea against Ottoman Turkish positions.

During these operations the seaplane carrier Ben-My-Chree, a particular thorn in the Turkish side due to the activities of her aircraft, was sunk by a Turkish battery on the island of Kastellorizo off the coast of Asia Minor. Her place was taken by the seaplane carrier Empress, which continued to annoy the Turks.

Another first for the RNAS was on 12 August 1915 when a Short 184 seaplane from Ben-My-Chree launched a 14in torpedo at a merchant ship in the Sea of Marmara, scoring a direct hit. This was the first time a ship had been attacked from the air in this fashion.

It transpired that the ship was already aground from an earlier attack by a British submarine, but this did not detract from the daring venture, particularly as five days later the feat was duplicated, sinking a troop transport in the same area.

As mentioned earlier (Chapter 14), the German cruiser Konigsberg was located in her place of refuge – the Rufiji Delta in East Africa – by a private exhibition pilot hastily commissioned into the RNAS and flying a leaky underpowered flying boat. She was eventually destroyed by two coastal monitors, Mersey and Severn, shooting on an unseen target hidden by jungle foliage 12 miles distant, thanks to the spotting reports supplied from RNAS aircraft.

Excellent though the seaplanes were, a larger and more robust type of aircraft capable of flying extended patrols deep into enemy controlled waters was required to counter the menace of the U-boat and to disrupt the reconnaissance activities of the scouting Zeppelins.

Following the sinking of the Cunard liner Lusitania in May 1915 and that of the White Star Arabic in August, the German Foreign Office were conscious that these acts had brought Germany and America to the verge of war.

The German Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg prevailed on the High Command to suspend the policy of unrestricted submarine warfare, which had been introduced as a counter to the British economic blockade.

With the danger of war with the United States temporarily averted, a number of U-boats were transferred from their North Sea bases to the Mediterranean, where for a period they caused havoc among Allied merchant shipping and inflicted disastrous losses on the British and French warships in the Dardanelles.

By March 1916, overriding the misgivings of their own Foreign Office, the policy of unrestricted submarine warfare was again resumed by the Germans, only to be suspended once more in April following further strong protests from the United States.

This situation lasted until February 1917 when, throwing caution to the wind, the ultimate phase of the policy of unrestricted submarine warfare was implemented, regardless of the protests of both neutrals and the United States.

During this period the German Navy had some 112 U-Boats operational, with eighty stationed at the North Sea ports of Ostend and Zeebrugge and a further twenty-two operational in the Mediterranean and Adriatic based in the Austrian port of Pola. In a single week in February 1917, thirty-five ships were sunk in the English Channel and the Western Approaches by u-boats.

Sopwith Pup aboard light cruiser Yarmouth. (Author’s collection)

As a result of these mounting losses, severe food shortages were being experienced throughout the British Isles, with some areas seeing actual starvation being a real possibility. There was civil disorder and food riots in several major cities, requiring the authorities to suppress these outbreaks with force.

Remarkable as it may seem, despite the seriousness of the situation, the Government still allowed market forces and private suppliers to control the supply and distribution of food, the effect of which ensured that the poorer section of the community were those who suffered most.

Food shortages continued to be of concern throughout the war until belatedly the Government introduced food rationing in mid-1918, a measure long overdue, to finally ensure a fairer distribution of the nation’s food resources.

At sea, intensive patrols were mounted by aeroplanes and airships, together with the provision of more surface patrol craft carrying depth charges and equipped with hydrophone detection equipment. These measures, along with the introduction of the convoy system, were ultimately to control the submarine menace.

The RNAS had acquired early in the war several examples of the Curtis H4 Small America flying boat which, although of limited range and performance, demonstrated the promise of further development.

These aircraft had been obtained through the efforts of a remarkable and dedicated reserve officer, Commander S.C. Porte, who in October 1915 was commanding the RNAS air station at Felixstowe.

Porte was well suited to the task in hand as he possessed considerable experience with flying boats, having earlier joined Glenn Curtis, the aviation pioneer at Hammondsport in the USA in 1913. In the US he assisted Curtis in the development of a twin-engined (later three-engined) flying boat that was being designed for the wealthy storeowner Rodman Wanamaker, specifically for a transatlantic flight attempt.

The attempt was scheduled for the autumn of 1914, with Porte as the pilot, the machine being delivered and tested before the outbreak of war, at which point the undertaking was abandoned.

Porte had previously held a commission in the Royal Navy from which he had been invalided in 1909 with tuberculosis, re-joining in 1914, where he argued the case forcefully for flying boats to be employed for anti-submarine and long-range reconnaissance work.

His proposals so impressed their Lordships that not only was he appointed to command the RNAS base at Felixstowe in September 1915, but he was also given a brief to develop the Curtis boats along the lines he had propounded.

The Admiralty had bought the original America along with several examples of the smaller Curtis H4 boats of two tons’ displacement, powered by two 180hp Curtis engines, which were generally adjudged to be inferior in performance to the contemporary British seaplanes then in use.

Porte’s first design was an enlarged and more powerful version of the Small America, the H12 or Large America. This was a much larger boat with a wing span of 90ft and powered by two Rolls Royce Eagle I engines of 275hp, giving a speed of 85mph, with the ability to climb to 11,000ft in 30 minutes and armed with four machine guns and four 100lb bombs.

These boats came into service in mid-1916 and, although the design of the planing hull displayed a structural weakness which required great caution during take-off and landing, the type proved to be a successful reconnaissance and anti-Zeppelin fighter. The first success against the latter by one of these machines took place on 14 April 1917 when Large America No. 8666 from Great Yarmouth air station under the command of Flight Lieutenant J.C. Galpin – with Flight Sub-Lieutenant R. Leckie as pilot, Chief Petty-Officer V. Whatling as wireless operator and Air Mechanic O. Laycock as engineer – left to patrol the waters around the Terschelling lightship, observing radio silence to avoid detection by the enemy.

After 1 hour and 30 minutes, Galpin and his crew spotted a Zeppelin dead ahead and some 10 miles distant. No. 8666 was at that time flying at 6,000ft, some 3,000ft higher than the enemy airship. Their prey was the L22 commanded by Kapitan Dietrich-Bielefeld, which was just turning to the north-east, having reached the southern limit of her patrol line.

Dropping their bombs to lighten ship, Leckie opened the throttles and, using broken cloud as cover, put the flying boat’s nose down, diving towards their quarry at over 100 knots, levelling out at her altitude at 75 knots and overhauling her on the starboard quarter.

From a range of 150ft, 8666 opened fire with the twin bow and midships guns, firing a complete tray of ZPT tracer from the forward gun and half a tray from the midships position before it jammed.

As the flying boat banked away to clear the gun, they saw a glow inside the envelope and within seconds the rear portion was in flames, quickly engulfing the entire framework, which fell stern first into the sea.

The cause of the loss of L22 was unknown to Strasser, as the Zeppelin had no time to send out a wireless message, so complete was the surprise of the attack. Strasser had to assume that the L22 had been lost to surface fire from British warships.

In his report Galpin stated that the L22 had been set alight before the German crew had realised the nature of the attack and the element of surprise together with their greater speed gave the flying boat the advantage. Galpin went on to say that, even under normal conditions, this type of flying boat should prove superior in every way to a Zeppelin, judging from the amount of power in reserve, and she proved an exceptionally steady gun platform.

The superior performance of these new flying boats forced the Naval Airship Division of the German Imperial Navy to abandon low Zeppelin patrol patterns in the German Bight and along the Dutch islands.

From now on, for safety, reconnaissance was to be conducted above 10,000ft, which lessened their ability to observe surface details effectively.

Further development of Porte’s original concept followed with the introduction of the larger and more seaworthy F2a boats, built with a much stronger double-stepped hull.

The F2a spanned 98ft, with a loaded weight of 5 tons and two 350hp Rolls-Royce Eagle III engines producing a top speed of 90 knots. These formidable craft mounted no less than six .303 Lewis machine guns, plus bombs and with an endurance of 8 hours.

Carrying a crew of four, they were the first true long-distance over-water reconnaissance aircraft, with a range of 600 miles, enabling them to scout large areas of the North Sea with rapidity.

In the offensive role the F2as could more than hold their own against the nimble and equally effective Brandenburg sea monoplanes and biplanes that they encountered on their incursions into the German Bight and along the Frisian Islands. They would sometimes form an attacking squadron of four or five boats against the German seaplane bases. In the course of these forays, long-running aerial duels were often fought.

When attacked by the German aircraft, the F2as would form into line astern, flying straight and level to engage the enemy machines with intense combined broadsides of machine-gun fire from their superior armament of up to six machine guns, in the same manner as that employed by Nelson Wooden Walls a century earlier.

As a Zeppelin destroyer the F2a proved to be an efficient and steady gun platform, with a fair turn of speed and a respectable rate of climb, and able to bring its powerful armament to bear on a Zeppelin with every chance of success. F2as were responsible for the destruction of two Zeppelins and made several other attacks in which, although the airships managed to avoid their fiery fate, they were forced to abandon their patrol duties early or had to climb to altitudes where their observations were rendered ineffectual.

The F2a’s greatest contribution possibly lay in its anti-submarine warfare role, together with its valuable contribution to mine-barrage spotting duties and the part it played in enforcing the blockade by reporting ships to the surface patrols on the lookout for blockade runners or contraband cargoes.

Alongside the numerous destroyers, mine hunters, CMBs and other patrol craft, airships and seaplanes, the F2as operating from Felixstowe, Great Yarmouth and other stations along the east coast were selected to fly the spider web patrols, starting in early 1917 and designed to counter the U-boat menace.

The central point of the patrolled area was based on the Nord Hinder light vessel, from where eight patrol lines radiated out for a distance of 30 miles, with concentric lines joining them at distances of 10, 20, and 30 miles from the centre, allowing 4,000 square miles of ocean to be systematically scoured with rapidity.

As the war progressed, the F2as and the earlier H12s became ever more active against the German seaplane bases along the Frisian Islands. They also flew long reconnaissance missions over the North Sea, attacking submarines and enemy merchant shipping and protecting the Allied convoys.

By mid-1917, the flying boat was able to perform all the duties with greater efficiency and reliability than those that had been attributed as the main role of the airship a few short years before.

Other devices designed to disrupt or destroy Zeppelins were also employed, including the towing of specially adapted lighters behind destroyers, carrying a single Sopwith Camel scout which could be rapidly brought to a suitable radius of action within enemy waters.

When a Zeppelin was sighted, the destroyer turned into the wind, working up to 30 knots, where the Camel after a run of 10ft was airborne.

By this method on 11 August 1918 Lieutenant S.D. Cully RN attacked and destroyed a patrolling Zeppelin, the L53, at the great height of 18,000ft off Terschelling, this being the last such airship destroyed in the war.

Only six days prior to this incident the leader of naval airships, the redoubtable Fregattenkapitan Peter Strasser, had been killed when the L70, the most modern airship of the fleet, had fallen in flames off the Norfolk coast with the loss of all her crew.

These losses marked the end of the Imperial Navy’s Airship Service as a fighting force, and by these actions in the last year of the war the aeroplane had proved its undoubted ascendancy over the airship in all aspects of operation, apart from that of endurance.

Another successful method by the fleet to warn of the presence of U-boats or minefields, was the use of kite balloons that were eventually carried in the ratio of one balloon at the rear of each division of four ships of the Grand Fleet when in cruising formation on North Sea sweeps.

These balloons, with a capacity of 30,000 cubic feet of hydrogen, were towed by a battleship at a height of 1,500ft, capable of being towed at the ship’s maximum speed. The observer in the basket would be in telephone communication with the battleship, from where he could, in suitable conditions, identify U-boats or minefields, and allow the divisional commander to call up destroyers or other light forces to deal with the situation.

Admiral Beatty also equipped six destroyers with kite balloons to accompany and scout ahead of the battle-cruiser fleet to perform similar duties and, more particularly, to extend the radius of his scouting line.

In August 1914 the Royal Naval Air Service was composed of fifty officers and 500 men flying thrity landplanes and fifty-eight seaplanes of indifferent performance.

By 1 April 1918 the service had expanded to 5,000 officers and 50,000 men, operating from forty-four aerodromes, fourteen airship stations and seven kite balloon stations.

Their equipment included 1,850 aircraft, including almost 1,000 seaplanes and flying boats, together with over 100 aircraft carried by the ships of the Fleet and even more at the time of the armistice.