By August 1916 a sufficient number of warships had been repaired following the damage inflicted on the High Seas Fleet at Jutland for Admiral Scheer to plan another raid on the English coast, with the target being Sunderland.The battle plan followed that of earlier raids, with the battle-cruisers Moltke and Von der Tann, the dreadnoughts Markgraf, Grosser Kurfurst and the newly commissioned SMS Bayern detailed for the task of making the assault, with the rest of the High Seas Fleet comprising sixteen battleships following some 20 miles behind.

From their experience at Jutland, and recognising the need for effective reconnaissance, Admiral Scheer ordered four Zeppelins to scout far out in the North Sea to warn of the approach of British ships, plus four further Zeppelins to scout directly ahead of the fleet itself. Additionally, twenty-four U-boats were positioned in the southern North Sea with the intention of ambushing the Grand Fleet, with the fleet setting sail from the Jade Basin at 9.00 p.m. on 18 August.

News of the German intentions had already been received via wireless intercepts that had been swiftly decoded in Room 40, who in turn alerted Fleet HQ that evening. On receipt of this information, the Grand Fleet at Scapa was led to sea in the early afternoon by Admiral Burney, later to be joined by Admiral Jellicoe, who, having been on leave, joined the fleet from the cruiser HMS Royalist later in the day at sea.

Vice-Admiral Beatty departed the Firth of Forth with six battle-cruisers and five battleships of the 5th Battle Squadron to join the main fleet of twenty-nine battleships off the Long Forties. In addition, the Harwich Force, comprising five light cruisers and twenty destroyers, had also put to sea, making best speed to a position off the western side of the Dogger Bank.

An early loss was that of the light cruiser Nottingham attached to Beatty’s force, which was hit by three torpedoes from the U-boat U52 at 6.00 a.m. on the morning of 19 August. It sank after an hour with minimal loss of life.

At 6.15 a.m., the Admiralty informed Jellicoe that the enemy was 200 miles to the south-east and later the same source informed him that the battle-cruiser fleet would be within 40 miles of the German fleet by 2.00 p.m. Jellicoe increased the speed of the fleet to maximum and, with good visibility and weather conditions, he felt confident of intercepting the German fleet before dark.

The High Seas Fleet in turn received a report from a patrolling Zeppelin that had sighted the Grand Fleet temporarily heading north, away from Scheer, to avoid a minefield. A further report from another airship, the L13, which had spotted the Harwich Force heading north-east, but mistakenly identified the cruisers as battleships, fortuitously caused Hipper to change course at 12.10 p.m. to the south-east, away from the approaching British fleet.

Unsure of the position of the British Fleet or their strength, Scheer prudently turned for home at 2.35 p.m. and aborted the raid on Sunderland. By 4.00 p.m. Jellicoe had received information that the German fleet had turned back to port and abandoned the undertaking, ordering his ships back to their bases.

At 4.52 p.m., the light cruiser Falmouth was hit by two torpedoes from the U52 and sank the following day while under tow, after being hit by two further torpedoes from the U66.

The Harwich Force sighted the German ships at 5.45 p.m. as they made for home, but were too far behind to attack them before nightfall and gave up the chase.

A final success for British forces came when the German battleship Westfalen was torpedoed at 5.05 a.m on the morning of 19 August by the submarine E23, commanded by Lieutenant Commander R. Turne, patrolling off the Jade Basin. The German ship, although damaged, managed to make it home.

This operation was the last occasion on which the High Seas Fleet approached British shores for the rest of the war and on 6 October the resumption of the policy of unrestricted submarine warfare meant that U-boats would not be available to the fleet to participate in any further raiding operations with them.

At the same time in September 1916 at a conference aboard the Iron Duke, it was decided that in the light of recent events it would in future put the fleet at unnecessary risk to undertake fleet operations below 55° North latitude – that is to say no further south than the latitude of Newcastle, unless some extreme emergency such as an invasion was undertaken by German forces.

A further German fleet operation took place on 18–19 October 1916 off the coast of Norway, and, although Admiral Jellicoe was made aware of the sortie through naval intelligence, he chose to leave his ships in port with steam up, as it was judged that the risks did not justify the possible results.

The Germans in turn failed to find the reported warships and abandoned the sortie after the SMS Munchen was struck by a torpedo fired by the British submarine E38, but made it back to port.

In November, Admiral Scheer ordered a division of dreadnoughts to aid two U-boats, U20 and U30, that had become stranded in fog on the Danish coast. The U30 was towed off and survived the war, but the U20 was stuck fast and had to be abandoned and blown up.

On the return trip, lying in wait off the Horns Reef was the British submarine J1 of 1,200 tons surface displacement and which was propelled by three 1,200hp diesel engines that delivered 19.5 knots, making them the fastest class of submarines in existence at that time.

The J1 successfully managed to torpedo two battleships of the squadron, the Grosser Kurfurst and the Kronprinz which, although seriously damaged, made it to port for subsequent repair. Commander Laurence of the J1 was awarded a bar to his Distinguished Service Order for his actions.

Since the Battle of Jutland, the High Seas Fleet had been largely restricted to its bases, rarely venturing into the North Sea in any force. But the fleet was employed in the Baltic against Russian forces in Operation Albion when, after eventually taking the port of Riga, the Naval High Command planned to seize the island of Osel and its gun batteries that controlled the entrance to the Gulf of Finland and the Russian naval base at Kronstadt.

For the operation beginning in September 1917 the German Navy deployed no less than twelve dreadnoughts, accompanied by nine light cruisers, and sixty torpedo boats. Against this formidable force the Russians attempted to defend the island with two battleships, an armoured cruiser and nine destroyers. Needless to say, the Germans prevailed and took the island, taking 100,000 prisoners and 100 guns.

It may come as a surprise to the reader that the convoy system that had been employed by the Royal Navy since the Dutch Wars, and that played such an important part of the war effort during the Second World War, was not instituted fully until 1917 in the Great War. The Admiralty’s main objection was that they lacked the necessary escort vessels and that a convoy presented a larger target to U-boats.

After much opposition from the Admiralty, the advantages were eventually accepted and in July 1916 the Harwich to Hook of Holland convoy, which had suffered from the attentions of the Flanders U-boat flotilla, was instituted. This was followed in February 1917 by similar protection being offered to the Humber to Bergen convoys and the trans-Atlantic convoys later in the year. But it was only at the War Council’s insistence, following the loss of 860,000 tons of shipping in March 1917, that the Admiralty finally consented to fully embrace the universal concept of the convoy.

In a change of policy, the new Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Fleet, Sir David Beatty, moved the battle fleet permanently from Scapa Flow down to Rosyth on the Firth of Forth from April 1918, bringing the fleet closer to the enemy, in order to more rapidly intercept any further incursions of the German Fleet, while still observing the principle of not risking the fleet further south than 55° N. The change from the lonely windswept Orkney Isles to the home comforts of shore leave in Rosyth or Edinburgh must have been very much welcomed by the crews, who could now enjoy the everyday pleasures of a sailor at liberty in port.

Fearful of exposing his ships on further raids on the English coast, Admiral Scheer next turned his attentions to the British convoys to Norway that were essential to the British war effort for its supplies of timber.

Using his light surface forces, two lightly protected convoys were intercepted and several merchant ships sunk in mid-1917, which persuaded the Admiralty to detail a squadron of battleships based at Invergordon to protect the convoys. Admiral Scheer saw this move as an opportunity he had been waiting for – to destroy a detached squadron of the Grand Fleet.

After several small-scale attempts to disrupt the Norwegian convoys throughout 1917, on 23 April 1918 Admiral Scheer organised a major operation to fall on the Norwegian eastbound and westbound convoys simultaneously, based on information communicated by Naval Intelligence.

Hipper’s battle-cruisers left the Schillig Roads heading northward to the Skagerrak, with the battleships of the High Seas Fleet leaving later to follow 20 miles behind Hipper’s Squadron in support. Unfortunately, although the battle-cruisers reached the rendezvous point undetected and on time, faulty intelligence meant that they had missed both the east and westbound convoys, each having sailed the day before.

Admiral Beatty had sortied with a force of thirty-one battleships and four battle-cruisers, but he was too late to catch the retreating German ships, highlighting the disadvantage the Grand Fleet was at and had been at for the past four years when the High Seas Fleet chose to conduct operations off the Norwegian or Danish coasts that were relatively near to their home bases.

A further disaster befell the Germans when the battle-cruiser Moltke, while steaming at high speed, cast a propeller, causing the turbine to race to destruction, damaging other machinery and flooding the engine room. The battle-cruiser was towed back to port by the battleship SMS Oldenburg.

On returning through the defensive minefields off Helgoland, the Moltke was torpedoed by the submarine E42, but despite this was able to reach port safely. The Moltke was subsequently repaired and conducted training programmes in the Baltic in September and October 1918, which effectively was the only relatively safe place for ships of the High Seas Fleet to operate in, so dominant was the Royal Navy’s control of the North Sea.

The German Army had launched an offensive in March 1918 on the Western Front as a final effort to defeat the Allies before the more than one million men of the United States Army could be deployed on the battlefield.

At this stage the Germans had the advantage of transferring almost fifty divisions of battle-hardened troops from the Russian front thanks to the cessation of hostilities with that country following the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

Initially, the Allies were taken by surprise by the offensive, which was very successful, with advances of up to 60 miles being made on the Somme and Aisne fronts – a scale of advance that had not been seen since 1914 – but rather less on the Belgium border and in the south on the Champagne and Marne sector. However, the Germans were unable to maintain the advance and ultimately, after suffering heavy casualties and plagued with logistical problems, lack of rations and supplies thanks to the British blockade, the offensive stalled.

In August 1918, an Allied counter-attack threw back the exhausted German troops, causing them to lose all the ground they had taken in the last five months, allowing the Allies to advance and break through the vaunted Hindenburg Line.

As the war drew to its now inevitable close in the latter months of 1918, Germany’s allies were crumbling one by one, with first Bulgaria seeking an armistice in late September and then Turkey entering negotiations for peace, which was eventually signed aboard Agamemnon on 30 October.

The High Seas Fleet were being increasingly troubled by a collapse of morale and discontent among the crews, who were concerned with a lack of rations and their conditions on board ships and in the barracks, even though they were better off than the soldiers fighting on the Western Front.

A general war weariness and political agitation was rife on the ships, which was related to the conduct of the war and a growing sense that Germany was doomed to lose the struggle.

Through the long months of inactivity as the ships of the High Seas Fleet remained swinging idly at their anchors at Kiel and Wilhelmshaven, the crews seethed with dissent that proved a fertile ground for political agitators to inflame the injustices real or imagined held by the sailors.

The effects of the punishment they had received at Jutland from the guns of British battleships had undermined the morale of the Navy as a whole and the majority of those officers and men who had experienced the battle were under no illusions about how close the High Seas Fleet had come to total annihilation and had no wish to be exposed to the guns of the Grand Fleet again.

By August the situation on the Western Front was desperate and General Ludendorff, while telling his army to hold their current positions, advised the Kaiser the war was lost and that a negotiated armistice was necessary.

On 24 October, with the German Army falling back to the frontier, Admiral von Hipper, now commanding the High Seas Fleet, planned a sortie. He took to sea the majority of the High Seas Fleet to confront the Grand Fleet in a final battle that it was thought would improve the German Government’s negotiating position at the armistice talks. However, the sailors of the High Seas Fleet had no intention of sacrificing themselves in an already lost cause and rose in rebellion against their officers.

On 29 October when the orders for the fleet to sail from Wilhelmshaven were issued, the sailors in three of the dreadnoughts of the 3rd Squadron mutinied and refused to weigh anchor. This was followed by sailors of the 1st Squadron on the battleships Thuringen and Helgoland, who also rebelled and sabotaged the ships’ engines to stop them putting to sea, while the officers had all but lost control over their crews.

Initially, a group of the mutineers were arrested, but by 4 November they were freed by thousands of their colleagues as the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Revolutionary Councils took over first the port of Kiel and then two days later Wilhelmshaven, with each warship being controlled by a sailors’ council. Under the influence of the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Revolutionary Councils, the revolution spread rapidly throughout Germany and on 10 November 1918 the Kaiser abdicated and crossed the border into exile in the Netherlands.

There followed a period of civil war between varying left-and-right wing political factions until in August 1919 a new constitution was adopted by the Weimar Republic, composed largely of social democrats and the Army, that became the legitimate government of Germany.

During the negotiations to settle the details of the armistice, the Allies insisted that the High Seas Fleet should be surrendered, but this was rejected by the German Government representatives, claiming that as the fleet had not been defeated it was unacceptable to them. The Allies reluctantly agreed on internment in a neutral port and approached Spain and Norway to take the ships, but both refused. It was then suggested by Britain that the German ships should be interned at Scapa Flow, and on 12 November the terms were delivered to the German Government, instructing them to have the High Seas Fleet ready for sea on 18 November.

The German representative crossed the North Sea on 15 November in a light cruiser to meet with Sir David Beatty on the Queen Elizabeth in the Firth of Forth, where the terms were presented to the German Government. Under these terms all the U-boats were ordered to proceed to Harwich where they were to surrender to Rear Admiral Tyrwhitt and the Harwich Force. For the U-boat, the weapon that had almost brought Britain to her knees, there was to be no question of mere internment.

The surface ships were ordered to sail to the Firth of Forth and to surrender to Admiral Beatty, from where they would be led to Scapa Flow to be interned pending the outcome of peace negotiations. Having no room for manoeuvre, Rear Admiral Meurer signed the document at midnight on the same day.

At Harwich, the first submarines began to arrive on 20 November, being escorted in by destroyers, with no show of emotion or cheering from the waiting British sailors, on the strict orders of Rear Admiral Tyrwhitt, to be anchored in long lines in the River Stour. Eventually 176 U-boats were brought into captivity, with several foundering, possibly deliberately, during the crossing. Under the terms of the surrender the German ships were to be demilitarised by removing the breech mechanisms of their main armament and the emptying of their shell rooms before departure.

In revolutionary Germany, rail transport disruptions and general shortages meant that the coal stocks necessary to carry the ships across the North Sea were so low that the scrapings of the coal dumps, including the dust, were required to provide sufficient bunkerage for the fleet.

The once proud ships of the High Seas Fleet posed a sorry sight as they prepared for sea; the long neglect during the months of inactivity spent in their harbours was evident in their peeling paintwork, rust-stained sides, dull brass-work and weed-covered bottoms.Admiral Hipper could not bring himself to face the humiliation of the surrender and the sad duty devolved onto Vice-Admiral Ludwig von Reuter, who in turn had been instructed by the chief of naval staff, Admiral Adolf von Trotha, that under no circumstances was he to allow the Allies to seize the ships, as they were still the property of the German Government, who expected them to be returned to Germany at the conclusion of peace negotiations.

On 21 November the ships of the High Seas Fleet, comprising nine (eventually eleven) battleships, five battle-cruisers, eight light cruisers and forty-nine torpedo boats, left the Jade Basin to a position 100 miles west of the Firth of Forth. The cruiser Cardiff, flying the flag of Rear Admiral Alexander-Sinclair, sailed out alone to meet the German fleet and led it to the rendezvous with the Grand Fleet 40 miles east of the Isle of May.

Admiral Beatty took the combined Grand Fleet and Allied warships, including nine American dreadnoughts and French warships, to sea shortly after the departure of the Cardiff in an assemblage of more than over 365 ships. This mighty array of sea power, their crews at action stations and with gun crews in anti-flash gear and gas masks closed up for action at their guns, headed eastwards to meet their enemies of the four-year war.

In the morning light in near perfect weather for the North Sea, with naval airships flying overhead, Admiral Beatty, on sighting the Cardiff approaching, formed the fleet into two long lines 6 miles apart, allowing the Cardiff to lead the German ships between the lines. At the correct moment Beatty ordered both lines to turn inward through 180° to bring Lion abeam of the German flagship of von Reuter, with the ship’s guns trained inward on the German fleet. The three columns of warships, friend and foe together, then shaped course for the Firth of Forth, with the Grand Fleet anchoring above and the German fleet below the Forth rail bridge.

The Queen Elizabeth, with Beatty on board, pulled out of line below the bridge to see the German ships pass to their anchorages. There was no cheering and little sense of elation among the officers and men of the Grand Fleet as their enemies, who over the past four years they had only seen briefly as vague fleeting shapes that disappeared into the mists, passed closely by.

There remained one final act to carry out, and at 11.00 a.m. Admiral Beatty transmitted a signal to Vice-Admiral von Reuter that the German flag would be hauled down at sunset and not be hoisted again without permission.

Over the next five days the German ships were escorted to Scapa Flow, with the move being completed on 27 November. The ships were anchored in lines on the west side of the Flow in Gutter Sound and off the island of Hoy.

In mid-December the majority of the ships’ crews were repatriated to Germany. Their numbers were now reduced from the 20,000 who had brought the ships into internment to 4,800, leaving only small skeleton crews to maintain the ships, awaiting the outcome of the Paris peace talks being held at Versailles that would determine the fate of the ships.

The peace talks continued for seven months. While it was in progress the British blockade was still in force, cutting off the supply of much needed foodstuffs to a starving populace, needlessly extending their sufferings. In the end, despite the harsh terms and the unrealistic reparations imposed on Germany, the German plenipotentiaries had no option but to sign the document.

At Scapa Flow during internment, the conditions on the German ships deteriorated under the Sailors’ Councils, which effectively controlled them. The lack of discipline and poor food, which had to be supplied from Germany, delivered once a fortnight together with the post. The crews were confined to their ships, and with little recreation or outside communication this led to the further demoralisation of the crews.

The living conditions quickly deteriorated, with the ships infested with rats, cockroaches and other vermin, and although a doctor was available to the fleet, there was no dentist and the British refused to supply one. The crews augmented their meagre diet by fishing and catching seagulls to eat, while Admiral von Reuter transferred from the Friedrich der Grosse to the cruiser Emden, as the Sailors’ Council on the flagship proved too difficult for him to deal with.

In the negotiations to decide the disposal or otherwise of the German fleet, France and Italy had hoped to receive 25 per cent each of the ships in reparations, while the British wanted to see all the ships destroyed, recognising that any redistribution would be detrimental to British interests.

On learning of the possible terms of the treaty in May 1919, von Reuter prepared plans for the possible scuttling of his ships in accordance with the instructions given to him by Admiral von Trotha in November.

At the same time, the British were aware that such action could be taken and, while keeping an eye on the situation, planned in turn to seize the ships by force immediately after the signing of the peace treaty.

The 1st Battle Squadron that was guarding the interned ships was under the command of Admiral Fremantle. Having been informed that the armistice that was to run out on 21 June had been extended until 23 June to allow the complex negotiations to be completed, he took the majority to sea for exercises on 20 June, leaving only a handful of destroyers and armed drifters on guard.

Believing hostilities were about to recommence on the morning of 21 June, Admiral von Reuter sent the signal ‘Paragraph 11 today acknowledge’ at 11.20 a.m. on that day to all ships and, in accordance with previously issued instructions, the crews opened sea cocks and flood valves, allowing the sea into the ships where all watertight doors and portholes were fixed open. By noon, watchers on shore noticed that the Friedrich der Grosse was listing to port and that all ships had hoisted the imperial battle flag.

Admiral Fremantle’s squadron was recalled to port, but only the battleship Baden and a handful of destroyers and one cruiser were saved or beached in shallow water. By 5.00 p.m. the bulk of the High Seas Fleet lay on the bottom of Scapa Flow. Ten battleships, four light cruisers and thirty-two destroyers were sunk. Nine German sailors were shot and killed, with nineteen wounded, while 1,700 others picked up from boats were sent as prisoners of war to the POW camp at Nigg.

Although the French and Italians were furious at the loss of ships they had hoped to acquire, the British, in the shape of the First Sea Lord Admiral Sir Rosslyn Wemyss, viewed it as a blessing in disguise, as it disposed of the contentious question of the redistribution of the ships among the Allies.

A salvage company was formed in 1923 that raised and scrapped four destroyers. This was followed by a larger company founded by Ernest Cox, who bought the rights to raise the German fleet for a nominal sum from the Admiralty in 1924, and with the aid of an ex-German floating dock raised twenty-four destroyers in eighteen months.

Cox next went on to raise the battle-cruisers SMS Hindenburg and Seydlitz, eventually raising five battleships, battle-cruisers and cruisers before the outbreak of the Second World War.

The battleships Konig, Kronprinz Wilhelm, and Markgraf, plus four cruisers still lie in deep water, protected under the Ancient Monuments & Archaeological Areas Act 1979. However, small-scale salvage was still carried out to recover small pieces of steel known as Low background steel (still used in research and by industry because it has not been contaminated with radio isotopes, as it antedates nuclear contamination from the mid-twentieth century).

In April 1919, the Admiral Sir David Beatty hauled down his flag: the Grand Fleet, having served the purpose for which it had been created, ceased to exist. They were reorganised into the Home, Atlantic and Mediterranean fleets, which were composed as follows:

Home Fleet – Admiral Sir Henry Oliver

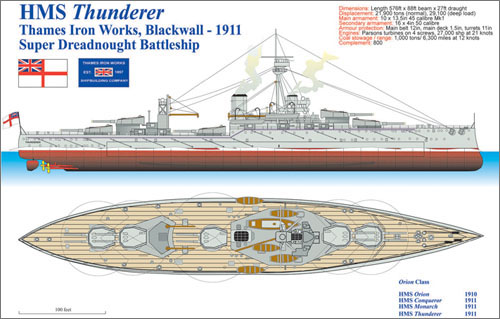

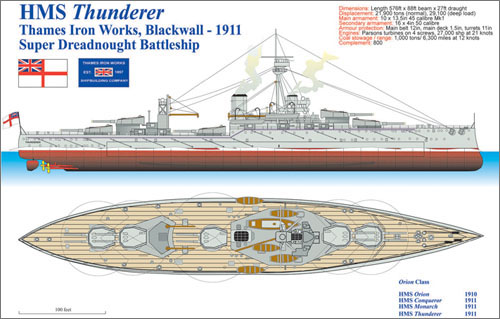

King George V, Orion, Monarch, Conqueror, Thunderer and Erin

Atlantic Fleet – Admiral Sir Charles Madden

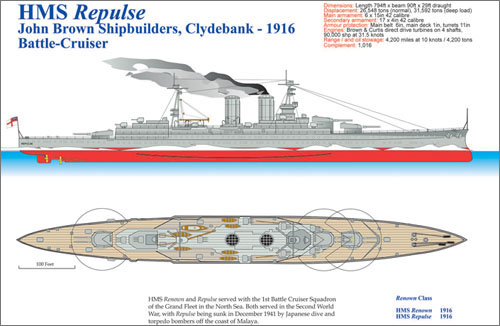

Royal Sovereign and Queen Elizabeth classes, battle-cruisers, Repulse, Renown, Lion and Princess Royal

Mediterranean Fleet – Admiral Sir John de Robeck

Iron Duke class Ajax and Centurion

With the war over, substantial reductions in personnel and ships had to be urgently made on the grounds of economy. At the time of the armistice in November 1918, the strength of the Royal Navy was 415,000 officers and men. By December 1919 this figure had been reduced to 162,000 officers and men. Similarly with ships, all of the older battleships, including the original Dreadnought and the battle-cruiser Indomitable went to the breakers between 1920 and 1922, together with ten of the earlier dreadnoughts and all of the old pre-dreadnoughts. All the old protected cruisers, armoured cruisers and the majority of the light cruisers, together with hundreds of destroyers, sloops, corvettes and other naval craft, were sold or went to the scrapyards in the early 1920s, their job done.

One final job remained for the Royal Navy to perform and that was the clearance of mines. During the war the Germans had laid an estimated 1,360 individual minefields in the proximity of the British coastline and harbours, comprising an estimated 20,000 mines, 90 per cent of which had been laid by the UC class submarine minelayers. British minelayers had laid 65,000 mines in barrages designed to control the exit through the Dover Straits, the Northern Barrage and mines laid in German home waters. Additionally, a further 11,000 mines were deposited in the Mediterranean Sea by the Royal Navy. The Admiralty undertook to clear these mines by the end of November 1919 and engaged officers and men who had previously been employed in minesweepers to volunteer for this specialised duty for a period of three months on extra pay.

This work was given the utmost priority in order to make the approaches to British harbours and shipping lanes safe for merchant traffic once again, where, thanks to the large number of minesweepers involved in an intensive programme of clearance, the greater part of the work was completed by December 1919 as planned, although individual drifting mines posed a hazard for many years to come. During this work they were assisted by the flying boats and airships of the Royal Naval Air Service in spotting minefields and individual floating mines from the air, either by destroying them by machine-gun fire from the air or calling up surface craft to deal with them.

In this task the RNAS airships were particularly useful, due to their long duration, as demonstrated by the cruise of the North Seas class airship NS11 with a Hydrogen capacity of 360,000 cubic feet giving a gross lift of 10 tons and powered by two 240hp. Fiat engines giving a speed of 70mph that made a continuous cruise of 101 hours, traversing 4,000 nautical miles on mine patrol over the North Sea in July 1919.