Before Europe plunged itself into the carnage of the Great War, two wars on the other side of the world at the end of the nineteenth century were to influence naval tactics and the design of capital ships. The first was fought between Japan and China and the second, a few years later, between Japan and Russia in the Far East.

In this period of great change and technological advance, new principles for conducting war at sea were being experimented with that were to result in incorrect interpretations and conclusions being put on the outcome of the various engagements by naval strategists and observers in both Europe and the United States. These would have misleading effects on the design of the next generation of warships, particularly in Great Britain.

The forced opening of Japan to trade was led by an American squadron under Commodore Perry in 1852. After initial resistance, a trade agreement, the Treaty of Kanagawa, was signed that ended Japan’s isolation, bringing them into the modern world.

Realising that their centuries-old way of life was to change irrevocably, the Japanese pragmatically adopted many of the western ways, integrating into the financial and political establishments of the western world. In particular, they embraced the rapid industrialisation of their country to build a modern society, while managing to maintain their unique Japanese culture. Recognising the need under these changed conditions of international involvement for the establishment of a navy, initially as a coastal defence force and later as a deep-water fleet, the Japanese turned first to French and German firms to supply the required ships, building a fleet that compared favourably with the generally similar collection of varied warships possessed by the other naval power in the Far East, China.

By 1894 the Japanese had instituted the centralised Meiji Restoration under an Emperor, as befitted an emerging modern state. This form of government replaced the earlier rule by the Shogun warlords.

The Japanese had for many years based the organisation, training and development of its fleet on that of the Royal Navy, as a pattern representing the greatest naval power on earth. They eagerly absorbed the ethos of that service to serve their own ends.

Britain supplied technical advisors to Japan to train their officers and men in all aspects of seamanship, tactics and weapon training and development. Japanese officers were trained in Great Britain, working in the shipyards where they could study the latest techniques in warship construction, and enrolled in British naval colleges, adopting the Royal Navy’s organisational systems, uniform and even its customs.

Thanks to the tutelage of British instructors, the Imperial Japanese Navy soon acquired a highly dedicated cadre of officers and men skilled in the arts of seamanship and gunnery unsurpassed by any other navy in the Far East. Additionally in this period the Japanese Government were ordering major warships from British yards.

The Chinese under the Qing Dynasty, on the other hand, were plagued by the demands of foreign powers, namely Great Britain, France and other European powers, who, during the 1840s and 1860s, had used force and persuasion to open a China weakened by natural disaster, famine and internal civil wars (the Taiping Rebellion in the 1850s and 60s was the bloodiest civil war in history with an estimated 30 million dead). Unrestricted foreign trade through a number of treaty ports compelled that country to become more closely involved with other foreign governments and with their policies and politics.

One potentially positive feature of this widening of Chinese international relations was the establishment of a modern navy, essential to protect her interests, which should have increased her international standing; in fact it had the opposite effect.

The Qing Government did not have a standing army and had to rely on tribal groupings to aid the central government forces on a regional basis. These tribal groupings often failed to provide support in time of trial. The most reliable fighting force was the Beiyang Army, composed mostly of Anhwei (Han) and Huai (Muslim) soldiers.

The corresponding Beiyang Fleet, established in 1888, was by comparison initially well equipped, with modern ships built in France and Germany, and symbolised a new and powerful China.

However, corruption among all levels of officials was widespread, with the wholesale embezzling of funds destined to maintain the navy being widespread among court and Admiralty officials in all departments and rendering the effective management of the service impossible. For instance, in 1895 30 million taels of silver earmarked for the construction of new battleships were diverted by the Dowager Empress Tzu-Hsi, who effectively ran the country and was the last absolute monarch, to reconstruct and enlarge the Summer Palace in Beijing.

This form of mismanagement and corruption spread rapidly through all departments of the Imperial Navy to the extent that even the supply of ammunition to the ships stopped in 1891, as funds were stolen by corrupt officials.

As time went on the ships’ fighting efficiency and condition deteriorated rapidly. In the case of one ship, even its guns were removed and sold to a local warlord. Poor levels of maintenance rendered ships almost useless as fighting units, while discipline and morale amongst the crews rapidly fell to an unacceptable level.

Against this background, Japanese expansion into Korea in 1894 provoked a war between the two countries, in which the Japanese Army soon asserted its superiority over the Chinese troops, entering Seoul in July 1884 and expelling the Chinese troops from most of the peninsula.

At sea, after a series of small naval actions in which the Japanese triumphed, a major engagement between the two fleets took place off the mouth of the Yalu River in September 1894.

The Chinese fleet consisted of two battleships, four large cruisers and assorted torpedo boats, while ranged against them the Japanese had a fleet of twelve modern warships. At this stage the Japanese did not have the financial resources to purchase modern battleships but instead adopted the French ‘Jeune École’ school, which propounded the theory of employing smaller and faster armoured cruisers that could outmanoeuvre and bring a rapid concentration of fire onto heavier, slower-firing enemy battleships, negating the advantage of their greater gun power.

During the battle the Japanese fleet comprehensively defeated the Chinese fleet, sinking eight out of ten of the Chinese ships.

The outcome of the battle caused foreign naval observers to draw the conclusion that lighter and faster ships could successfully fight battleships, a misconception that was to adversely affect tactical thinking and design in varying degrees for some years to come.

In the course of the battle the Chinese Beiyang fleet disposed in line-abreast, opening fire ineffectually at the then great range of 6,000yd, while the faster Japanese warships passed diagonally across their front, closing the range to 3,000yd, where the combined rapid fire of their lighter weapons was used with terrible effect.

As no major naval action had taken place since the Battle of Navarino in 1827, a major problem facing naval strategists at this time was that when the Turkish fleet was defeated by the combined British, French and Russian fleets, they had no experience of battle in the light of the innovative technical developments that had taken place in the intervening years.

Japan, now established as a major naval power and with an expansionist foreign policy, began to build up her fleet with modern battleships, ordered from British shipyards in increasing numbers.

While Japan had been heavily involved in military and naval operations in Korea against the Chinese since the 1890s, the corresponding Russian expansion in Manchuria and the acquisition of the port of Vladivostok in 1860, together with the later extension of the Trans-Siberian Railway, served to increase tension between the two countries, with numerous border incidents taking place over the years leading up to the twentieth century.

Finally, in February 1904, without a declaration of war, Japanese naval forces attacked the Russian fleet anchorage of Port Arthur on the Liaodong Peninsula at night with torpedo boats.

This attack resulted in two Russian battleships and a cruiser being sunk in the harbour and the remaining ships being trapped by the rapidly advancing artillery of the Japanese Army.

Over the next few months the Russians suffered a series of military defeats and eventually all the Russian ships in Port Arthur were sunk by shore-based artillery fire.

Prior to this disaster, efforts were made to reinforce the Russian Pacific fleet by sending almost the whole of the Baltic Fleet halfway round the world on a trip of 18,000 miles that took 8 months to accomplish.

The fleet, now renamed the ‘Russian Second Pacific Squadron’, under Admiral Rozhestvensky – a capable commander, but hampered by the quality of ships at his disposal and the poor discipline of the crews – sailed from the naval base at Kronshtadt. This motley collection of ships was unsuited to working together in line of battle due to its mixed armament and inability to manoeuvre effectively as a unit.

While passing down the North Sea in October 1904, the jumpy Russian gunners opened fire at night on British fishing boats, under the impression that they were Japanese torpedo boats. This event, in which several British fishermen were killed and wounded, became known as ‘the Battle of Dogger Bank’, and caused a diplomatic incident, resulting in an indemnity to be demanded of the Russian Government and the Russian ships being escorted as far as Gibraltar by warships of the Royal Navy.

By the time the Russian fleet finally reached the Far East, Port Arthur had already fallen, so Admiral Rozhestvensky elected to pass through the Straits of Tsushima to reach the only other free Russian port of Vladivostok.

However, the Japanese Admiral Togo, leading a fleet of four fast battleships, six armoured cruisers and other smaller craft, crossed Rozhestvensky’s ‘T’, the classic manoeuvre in which a line of battleships cuts across the line of advance of an enemy fleet, thereby bringing a devastating barrage of fire to fall on the enemy van.

A feature of battle was the extreme range at which the Russians initially opened fire, at some 7,500yd with their heavy 12in and 10in guns, which were capable of only around two rounds per minute.

Admiral Togo calculated that his ships were in little danger of being hit at this range and accordingly turned toward the Russian ships to close the range passing diagonally across their front.

The Russian secondary armament scored the first hits but, as the range closed rapidly to 5,000yd, the superior Japanese gunnery and rate of fire had its effect. Rozhestvensky tried to close the range to improve the chances of obtaining hits with his main and secondary armaments, at the same time turning to starboard to avoid having his ‘T’ crossed.

The two fleets continued on parallel courses to the north-east at a range of 5,500yd, with the Japanese pounding the Russian ships to which they could only make an ineffective reply.

The Japanese battleships – the flagship Mikasa and the Shikishima – fired on the Russian battleship Suvorov, their shells bursting with terrible effect. Soon the other battleships, Alexander III, Osliabia and Borodino, were heavily engaged and by early evening all four were sunk, with the remaining main unit Orel being badly damaged and captured, together with the rest of the fleet that had not either been sunk or had escaped to neutral ports.

One of the features of the battle from which later spurious conclusions were drawn was the inclusion of four armoured cruisers in Admiral Togo’s battle line. While the four battleships (15,000 tons) were armed with four relatively slow-firing heavy 12in guns, the armoured cruisers (9,000 tons) carried mixed batteries varying from 10in to 8in, together with up to fourteen 6in quick-firers.

Additionally, these ships had adequate armour protection for the period, and were capable of steaming at over 21 knots, which was considerably faster than the Russian battleships, and could also deliver a telling weight of shot against the Russian ships.

The armoured cruisers’ 8in guns could deliver five 250lb shells per minute and the 6in guns eight 100lb shells in the same time.

It was the most comprehensive defeat of one fleet by another, and a modern one at that, since Nelson’s victory at Trafalgar almost one hundred years before. The effect of the defeat of a major European nation by an Asiatic power was not lost on the chancelleries of Europe and gave cause for concern at the Admiralty that its Far Eastern protégé had grown into such a powerful sea power in so short a time.

While these events were being played out in the Far East, the results were being analysed by naval strategists in Europe and the United States. The enormous 7,000yd range, as it was then seen, at which both fleets opened fire and the mixed calibre of the armament, posed a whole new set of problems to the tacticians. The fact that both sides failed to register hits at extreme range, only hitting their targets when the range closed to around 4,000yd, was not recognised as a failure, but rather encouraged naval observers to predict that future battles would be fought at these extreme ranges, which, although a correct observation, would need a complete change of tactics and equipment to implement.

At these ranges the existing fast-burning propellant powders produced irregular rates of burn that militated against achieving an accurate fall of shot. Also it was impossible to differentiate between the shell splashes of the mixed-calibre weapons together with the slow rate of fire of say a 12in gun (one shell every 2 minutes), that enabled a target to turn away between salvoes, making the gunlayer’s task almost impossible in calculating the ‘rate of change’ of a target and correcting their aim.

Prior to the Battle of Tsushima, the Admiralty, in the shape of the gunnery expert Captain Percy Scott, was studying the problems of improving the accuracy of gunnery at extreme range and the tracking of a target.

The introduction of large-grain, slower-burning propellant charges greatly improved the accuracy of the fall of shot while eliminating the tendency for the shell to tumble towards the end of flight and keep on target.

The introduction of long-based optical range finders went some way to allowing a more accurate assessment of the enemy’s range and position, and in battle practice the percentage of hits recorded to number of rounds fired improved from 31 per cent in 1895 to 71 per cent in 1905.

An important innovation introduced by Captain Scott was the director fire control system, an early analogue computer device that could predict the course and position of the target and accurately direct the fall of shot, while allowing for adjustment of the range and deflection to keep subsequent salvoes on target.

One of the false conclusions drawn from the Japanese victory was the belief that armoured cruisers with their lighter, quick-firing weapons could take on and defeat battleships in line of battle.

This misconception to a degree influenced Britain’s Admiral ‘Jacky’ Fisher, then First Sea Lord, who was already planning a class of fast, heavily armed but lightly protected cruisers that were to become the battle-cruisers. These were shown to be a flawed concept when three were lost at the Battle of Jutland, together with three of the earlier armoured cruisers.

Naval architects fought a continuing struggle against the increasing penetrating power of ever more powerful guns and the need to provide adequate armour, protection that could only be achieved at the expense of an increasing weight penalty that had to be balanced against the requirements of speed, gun power and displacement.

The early wrought-iron armour of the Warrior was soon replaced by compound armour, which consisted of iron sheets faced with steel, forming a sort of composite sandwich. Effective though this arrangement was initially, soon the increasing power of the new breech-loading guns required a more resistant form of armour. In the Majestic class battleships of 1895 it was replaced by Harvey case-hardened steel plate within a 9in-thick main belt.

This armour originated in the USA and was manufactured by the Carnegie Steel works. The hardening process involved sandwiching carbon between two steel plates at high temperature in the furnace for an extended time before quenching in water to surface-harden the plates.

At the time, this armour gave protection from a 12in shell fired from 4,000yd. The Harvey, case-hardened armour of steel plates in a 9in-thick belt, 16ft in depth had the equivalent resistance of the 18in composite armour of the earlier classes.

A little later, the German firm of Krupp introduced a hardened steel plate of nickel steel from 1in to 12in thickness that broke up all projectiles fired in test firings. Following this success, British shipbuilders employed nickel steel armour in subsequent battleships.

From the 1860s, advances in metallurgy and precision mechanical engineering enabled guns to be manufactured, employing such advances as breech loading (perfected by Armstrong), together with the interrupted screw thread (a device developed by the French that closed the breech with a one-third turn) and the advent of rifling that imparted spin stability to the shell in flight. All of these advances contributed to the advent of the modern long-range naval gun.

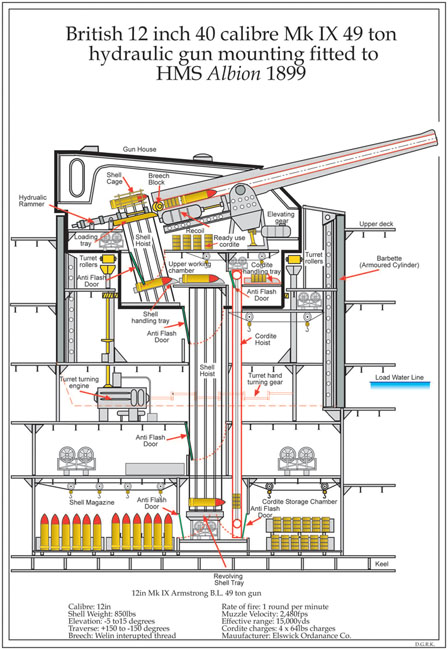

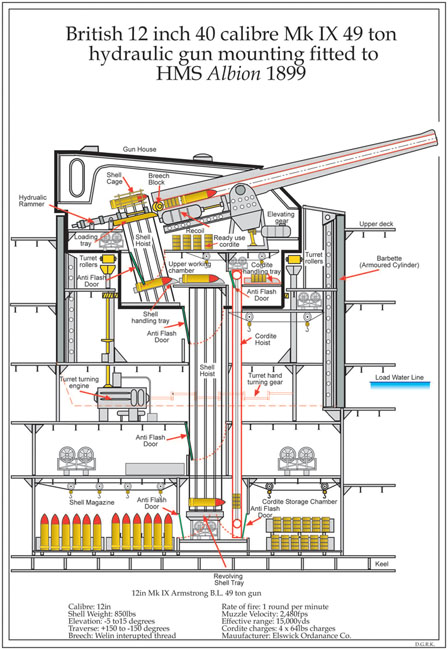

Naval guns were constructed as a series of forged tubes of differing diameters that were heated and shrunk to fit over each other, with the area around the breech – where pressures of up to 200,000lb per square inch would be experienced – being reinforced by multiple layers of tubes in that area.

The bore of the innermost ‘A’ tube was machined internally, with a series of spiral grooves or ‘lands’ (typically one and a half turns of the barrel length) that engaged the driving bands on the base of the shells to impart spin stability to the projectile. The ‘wire wound weapon’ was a further method of reinforcement against the tremendous pressures exerted in the breech chamber when the gun was fired. This consisted of winding the outer surface of the innermost rifled ‘A’ tube with up to 120 miles of a steel wire ribbon, over which the second ‘B’ tube was then shrunk on to. This process not only strengthened the tube against the detonation of the propellant charge but also increased the accuracy of the gun.

The standard British naval gun, as mounted in the battleship HMS Albion of 1899, was the 12in Mk IX 40 calibre weapon. It could fire a 850lb armour-piercing shell at a muzzle velocity of 2,480fps, for a distance of 15,000yd at 14° elevation and could penetrate 12in of Harvey or Krupp hardened steel plate at 3,500yd.

The later Mk X 45 calibre 12in gun of 1906 could fire a shell of similar weight, but with an increased muzzle velocity of 2,700fps to a range of 25,000yd at 30° elevation. This model of gun, with minor modification, remained in use until 1945.

In the Albion, 300 to 400 shells were stored in the shell rooms and magazines for each gun, where three main types of shell were in use – common, armour piercing and high explosive. These were filled either with powder or the newer Lyddite.

The shells and projectile charge were brought up from the magazine and handling room by the mechanical shell hoists into the turret where the shell was rammed into the breech, followed by the cordite charge, which, in British ships, consisted of a bundle of tightly packed, extruded cordite sticks bound together by tape and enclosed in a silk cloth bag forming the cartridge.

This seemingly Heath-Robinson arrangement was standard practice throughout the time these large calibre guns remained in service with the Royal Navy, although all smaller calibre weapons had brass cartridge cases with the shell attached as a single unit.

It is noteworthy that from the outset the Imperial German Navy chose to employ sealed brass cartridge cases for all calibres of gun, including their 11in (280mm) main armament guns, which was to give them greater protection from flash fires if a turret was hit, unlike the British ships where a hit on a turret could send tongues of flame down the ammunition hoists into the handling rooms and magazines, setting off the exposed charges with fatal results.

The main weapon fitted as secondary armament to battleships and mounted on destroyers in the 1900s was the 4in Mk1 quick-firer, which fired a 31lb projectile at a muzzle velocity of 2,600fps for 13,700yd at a rate of ten shells per minute. Later Dreadnought battleships had their secondary armament upgraded to the Mk IX 6in QF gun, which at an elevation of 15° could throw a 100lb shell a distance of 13,500yd, with a maximum rate of fire of six rounds a minute. This weapon was also favoured as main armament for the new generation of Dreadnought light cruisers, such as the HMS Arethusa and later wartime classes.

A weapon that was to have increasing importance over the years in naval arsenals was the locomotive torpedo, as it was originally known, first proposed by an Austrian naval officer, Captain Lupus, and developed by the British engineer Robert Whitehead at his factory in Fiume on the Adriatic in the 1860s.

Early versions of the torpedo were of limited range and were so slow that they could be outrun by the attacked ship steering away from the track in the opposite direction, but by 1893 a torpedo establishment had been set up at HMS Vernon in Portsmouth to develop the weapon for the Royal Navy. By 1906 torpedoes of the Whitehead design, powered by a compressed air piston engine carrying a warhead of gun-cotton and pressure-firing pistol, had a range of over 1,000yd and could travel at a predetermined depth below the surface at up to 35 knots, with a reasonable degree of accuracy steered by gyroscopic control.

A further improvement in performance was the provisoin of greater power and range. This was acheived by heating the air in the compressed air reservoir, either by burning paraffin or discharging a shot-gun cartridge internally to substantially raise the air temperature.

Torpedoes were initially installed in battleships in submerged beam and bow tubes, for defence. At the same time, torpedo boats – small, fast, light craft – were being developed, whose function it was to attack larger vessels.

These torpedo boats were in turn countered by the introduction of the torpedo boat destroyers, which were much larger and more heavily armed ships that eventually took over the duties of the torpedo boat and became known simply as the destroyer, and which usually included a heavy torpedo armament.

The effectiveness of torpedo boats and destroyers was shown in the First World War when Italian motor torpedo boats attacked and sank the modern Austro-Hungarian dreadnought Szent Istvan with two torpedoes off the Dalmatian coast in 1918.

The torpedo was also to become the main weapon of the submarine, which the British introduced into the Navy in 1900, with the Germans following suit in 1908.

During the First World War Germany employed her U-boats in pursuing the Guerre de Course of commerce raiding. This was to prove so effective that at one stage during 1917 Britain’s merchant shipping losses were so heavy that it was in danger of starvation.

So by 1904 great changes were taking place in the way the war at sea would be fought in future conflicts, with the introduction of the steam turbine and the development of the long-range naval gun, submarine and torpedo.