Britain’s long preoccupation with viewing France as a potential enemy over the preceding century had allowed military planners to largely disregard the building of extensive defensive works along the east coast; a region that was now seen to be dangerously unprotected and at risk of invasion from the sea.

It was along the flat coasts of Norfolk, Suffolk and Essex that the fear of invasion was most strongly felt in the years leading up to the Great War, as tension between Great Britain and Germany increased.

The British public, increasingly literate since the Elementary Education Act of 1870 that called for the compulsory education of children up to the age of thirteen, had for many years, thanks to the availability of cheap newspapers and magazines, taken an altogether more informed interest in politics and world affairs. The novel had become a popular diversion for this literate public and, following the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, in which an increasingly militaristic state, Prussia, had invaded and overwhelmed Europe’s largest army in a matter of weeks (thanks to modern weapons and modern methods of warfare), the public felt a sense of unease that a new threat faced our islands.

This popular anxiety was immediately taken up by the author George Tomkyns Chesney, who, in 1871, produced the book The Battle of Dorking, the first of the genre of several hundred ‘invasion scare’ stories produced over the next forty years, up to the outbreak of the Great War. In The Battle of Dorking, an unnamed foreign army, that happen to speak German, invade the British Isles and, despite heroic resistance, they subject the country to their will.

Other works also led the British public to increasingly regard Germany as the potential enemy. These included Erskine Childers’ The Riddle of the Sands of 1903, describing a seaborne invasion of the east coast, and H.G. Wells’ The War in the Air of 1907, which describes a world war precipitated by the expansionist ambitions of an Imperial Germany. And then there was the self-styled secret agent and author, William le Queux, whose novel The Invasion of 1910 again casts Germany in the aggressor role. Fuelled by these anti-German stories regarding possible invasion, a spy mania swept the country in the early years of the twentieth century, which in turn created calls for action on the part of the Government. In response they founded the ‘Secret Service Bureau’ that was to be the forerunner to MI5 and MI6, with the home section of the agency occupying itself by tracking down spies and saboteurs, although in fact no extensive network of spies existed in the country.

The main result in the years before the Great War of this anti-German invasion genre was to promote in the minds of the average Englishman the inevitability of war between the two countries. Voices were raised against this scare-mongering, such as when the Prime Minister Henry Campbell-Bannerman denounced Le Queux’s book The Invasion of 1910 as ‘Calculated to inflame public opinion abroad, and alarm the more ignorant at home’, but by then the seeds of conflict had been irrevocably sown.

As previously mentioned, while no actual invasion took place, the German High Command at the outbreak of war had expected, and indeed hoped, that the Royal Navy would impose a close blockade of their coast in the manner of that conducted during the Napoleonic wars against Brest, Toulon and other ports that had proved so successful in containing the French fleet.

It was hoped that under these favourable circumstances, with British warships patrolling close inshore to German naval bases, opportunities to sink them by use of submarine and mines would be greatly increased, or possibly to intercept smaller, isolated squadrons and lure them into a trap against superior enemy surface units in conditions that favoured the defending force. In the event the British had already come to the conclusion that with the advent of modern weapons the principle of close blockade was no longer a viable option.

Accordingly, plans were put in hand as early as 1908 that, in the event of war with Germany, Admiralty policy would be to close off the entrances to the North Sea from the Channel in the south and between Norway and Scotland in the north. The intention was to achieve the double goal of restricting the flow of foodstuffs and raw materials to Germany with an economic blockade and, conversely, to reduce the possibility of German surface raiders leaving the North Sea to prey on Britain’s merchant shipping on the world’s trade routes.

After some preliminary skirmishing between individual light units and the capture and sinking of AMCs and minelayers, it became more obvious that the British had no intention of offering themselves up as targets for torpedos and mines in a close blockade. The Commander-in-Chief of the High Seas Fleet, Admiral Friedrich von Ingenohl, resolved to use the High Seas Fleet in an aggressive manner, seeking out the enemy as occasion and opportunity warranted. But in this he was frustrated by the Kaiser who was intensely protective of the fleet he had created and was loath to risk his ships, and insisted that the fleet was not to put to sea without the express orders of the Kaiser himself. In his caution he was reinforced by an incursion into the Heligoland Bight by a strong force of Royal Navy ships in August, including battle-cruisers, when the war was only three weeks old, that fell upon patrolling German light forces sinking three light cruisers.

On the other side of the coin the dangers to the Royal Navy of operating in the waters close to the German coastline was dramatically illustrated in September 1914 when three armoured cruisers patrolling at 10 knots in the Broad Fourteens off the Dutch coast were sunk in turn by a single submarine in an afternoon.

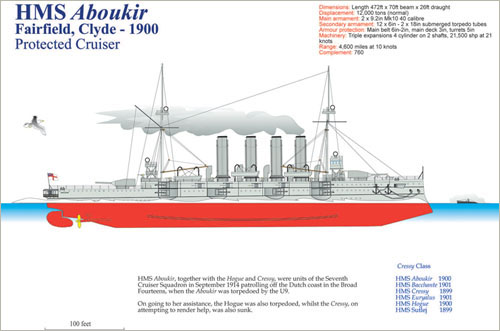

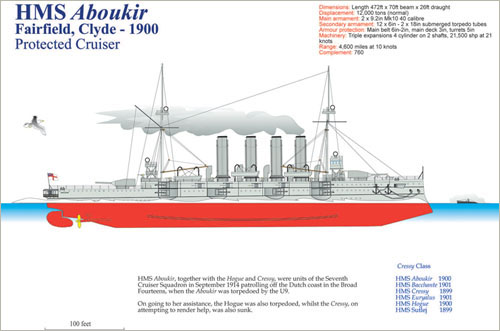

The armoured cruisers HMS Aboukir, HMS Hogue and HMS Cressy of the 7th Cruiser Squadron based at Dover, under the command of Captain Drummond of the Aboukir, were sister ships launched in 1902, each of 12,000 tons’ displacement, mounting two 9.2in and twelve 6in guns apiece. They were cruising slowly at 10 knots in line ahead parallel to the Dutch coastline in the early morning of 22 September 1914, after their accompanying destroyers had been detached to refuel.

Unwisely, the ships were not steaming on the recommended zigzag course –the correct procedure in hostile waters – which made it easier for Kapitanleutnant Otto von Weddigen who, while running submerged, had sighted the trio from his U-boat U9 of 500 tons’ surface displacement and one of the earliest German submarines built.

Manoeuvring into an optimum position across their track, he fired a single torpedo from under 1,000yd range that struck the Aboukir amidships on the port side around 6.30 a.m.

Believing that she had struck a mine and having seen no torpedo tracks, Captain Drummond ordered the Hogue to his assistance as his ship began to settle, to aid in the rescue of survivors.

Captain Nicholson of the Hogue came alongside and lowered boats to help with the rescue, when at 6.45 a.m. the U9 fired two torpedoes at the Hogue from a range of only 300yd, hitting her amidships on the starboard side.

The Hogue’s boiler room flooded rapidly and within 10 minutes she slipped beneath the waves, followed at 7.00 a.m. by the Aboukir, rolling over on her beam ends and going down in a welter of steam with her screws still turning.

The third cruiser Cressy hastened to the aid of the two stricken ships and was in turn herself torpedoed, quickly followed by a second torpedo from U9 10 minutes later, exploding on her armoured belt at 7.20 a.m. where, after listing heavily to starboard, the Cressy sank at 7.35 a.m. carrying all but fifteen of her crew to the bottom. Within the course of an hour three large warships and 1,880 officers and men, many of them reservist or cadets, had been lost to one of the oldest U-boats in the German Navy.

On their return to Wilhelmshaven von Weddigen and his crew received a hero’s welcome and were decorated and feted.

The following month, von Weddigen repeated his success with U9 when on 15 October he sank HMS Hawke, a protected cruiser of 7,700 tons built in 1891 in the North Sea, with a single torpedo that hit her magazine, causing the ship to explode with the loss of all hands.

Otto von Weddigen was later to meet his nemesis when in March 1915 his next command, the U29, was rammed and sunk by Dreadnought in the Moray Firth, with the loss of von Weddigen and his crew. It is interesting to consider that the revolutionary dreadnought – the ship that ushered in new concepts of the war at sea – should employ the most archaic of naval weapons, the ram, to gain her victory.

In Britain the news of the loss of three armoured cruisers to a U-boat was received with disbelief and profound shock, while the Admiralty were forced to realise that the submarine which had been seen as a peripheral weapon of doubtful use, apart from perhaps harbour defence or patrolling inshore coastal waters, was in fact a dangerous new weapon of great potential that could fundamentally affect the balance of power at sea.

A hastily convened court of inquiry was held, at which Captain Drummond was criticised for his failure to follow a zigzag course as contained in his orders, while the senior officer of the squadron, Admiral Christian, was similarly criticised for his lack of leadership and failing to follow correct procedures, instituting these high-risk patrols using old ships in distant waters that were of limited value, against repeated advice from experienced senior officers.

Although these older ships, of which the Royal Navy possessed around thirty-four armoured cruisers and twenty-odd protected cruisers that had been built since 1900, were still of considerable use in their scouting function to the fleet, they were patently inferior to the modern types of turbine-driven cruisers and in almost any engagement would be at a severe disadvantage.

Although most of the later armoured cruisers were still attached to the Grand Fleet, from now on they were employed with greater circumspection now that their inherent weakness had been exposed and were increasingly detailed to the less dangerous work of trade protection. As a result of the disaster, these patrols were suspended and the practice of major units stopping to go to the aid of their fellows in enemy waters was banned, with any rescue being affected by destroyers or smaller craft if practical.

Frustrated by the British policy, the German Admiralty devised a series of raids on the English coast that would not only deliver a propaganda coup to the German nation, but could possibly lead to the isolation of a section of the Grand Fleet, by drawing it into a trap consisting of a squadron of superior heavy ships placed across the British line of advance and preferably located in an advantageous tactical position in or near to German waters.

Admiral Friedrich von Ingenohl proposed a daring scheme to take a squadron of battle-cruisers and light cruisers on a lightning raid on the British east coast, the first target chosen for this raid being the port of Great Yarmouth. Accordingly, at 4.30 p.m. on 2 November, the battle-cruiser squadron under the command of Admiral Reinhard Scheer left Wilhelmshaven in the Jade Basin heading westward. It was to be followed by two squadrons of battleships sailing some hours later that would be positioned several miles behind the battle-cruisers, ready to fall upon any British ships that might be enticed into pursuing Scheer’s ships into a trap.

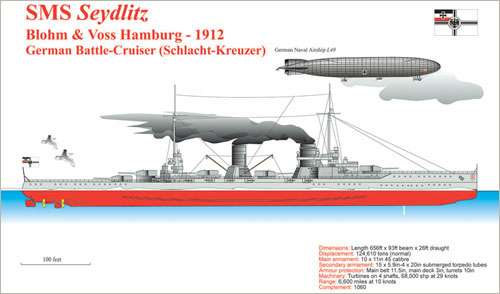

In the early morning light of 3 November 1914, the old gunboat HMS Halcyon, patrolling off the Cross Sands light vessel, sighted and challenged a group of unknown vessels emerging from the mist to seaward. Halcyon’s challenge was met with a withering blast of fire from the German battle-cruisers Seydlitz, Von der Tann and Moltke, the armoured cruiser Blucher and three accompanying light cruisers, commanded by Admiral Franz von Hipper.

Against these overwhelming odds, the Halcyon pluckily returned fire with her two 4.7in guns before seeking shelter in a smoke screen laid by the destroyer HMS Lively, which allowed the gunboat to turn away with only minor damage and escape to the south-west, raising the alarm with a wireless message of the presence of enemy ships close inshore.

The German squadron standing off Great Yarmouth then proceeded to bombard the town for 30 minutes with their 11in-high explosive shells – which fortunately did little damage, with most of the shells landing on the beach – while the light cruiser SMS Stralsund laid mines along the coast. In the harbour four destroyers were raising steam, while three submarines prepared for sea. One of these ran onto a mine near the harbour entrance and was lost.

At 10.00 a.m. Admiral Beatty, alerted to the raid, led the 1st Battle-Cruiser Squadron south from Rosyth on the Firth of Forth in hope of intercepting the raiders, but by that time Hipper’s ships were already 50 miles east of Great Yarmouth. The returning German ships were delayed by fog from entering harbour and anchored overnight in the Schillig Roads. In the fog, the armoured cruiser SMS Yorck, which had not been involved in the raid, while crossing the Jade estuary went off course and ran into a German defensive minefield, sinking with a heavy loss of life.

The raid could be seen as a propaganda victory for Germany, particularly among the neutral nations and, although little material damage had been done, it did demonstrate the ability of the German Navy to raid the British coast with impunity. On the British side, with a submarine lost and twenty-three killed, the lack of an effective response to this form of incursion exercised the minds of the Lords of the Admiralty as to the best way to respond.

The widely publicised news of the raid coincided with the receipt at the Admiralty in London on the same day of the report of the loss of the Good Hope and Monmouth of Admiral Cradock’s squadron at the Battle of Coronel off the coast of Chile. This added to a feeling of outrage and disbelief from the general public, who had long trusted in the invincibility of the Royal Navy and had expected them to be successful in any confrontation with an enemy.

In government circles the ease with which the German ships had been allowed to approach Britain’s coast (to be met with only minimal resistance) was a worrying development that exposed a lack of an integrated and effective scheme to protect Britain’s east coast harbours and shipping lanes from this form of incursion.

Additionally, the raid seemed to be a portent of worse to come and in response the Government hurriedly stationed two additional regiments of infantry in East Anglia, should these raids be the precursors to an actual invasion. At the same time, the naval bases at Dover, Harwich, Great Yarmouth and Sheerness were reinforced with additional destroyer and cruiser flotillas, while the battle-cruiser squadrons remained at their northerly harbours.

The Germans had hoped that by this and later raids it would persuade the Admiralty to bring a portion of the battle-cruiser fleet south and encourage the dispersal of other units to protect the east coast, thereby increasing the chance of the Germans catching an isolated group of British ships in a trap during a subsequent sortie, while at the same time weakening the main fleet at Scapa Flow.

The Commander-in-Chief of the High Seas Fleet, Admiral Friedrich von Ingenohl, was satisfied with the outcome of the raid, as, more importantly, was the Kaiser (although still ever fretful about hazarding his ships). Its success, together with the news of von Spee’s victory, did much to boost the confidence of the fleet and encourage a more aggressive and daring use of its ships in future.

Buoyed up by the success of the Yarmouth raid, von Ingenohl now proposed an even more ambitious raid, with the chosen target being the Yorkshire coastline between the River Humber and Hartlepool.

From early August, German minelayers had laid mines along the coastwise sea lanes and at the approaches to the ports of Hartlepool, Scarborough, Whitby and Hull, resulting in a number of merchant ships being sunk. The British, in turn, attempted to keep the approaches to these harbours open by sweeping the channels, initially employing drifters and other fishing craft for the task until specialist mine sweepers could be developed.

The German mines were laid by fast converted merchant ships, or Hilfekreusers, which could carry up to 300 mines, laying them during the hours of darkness before fleeing back to their bases, eluding the Royal Navy patrols.

In choosing to attack ports on the Yorkshire coast, von Ingenohl was taking a greater risk with his ships, as these targets were much closer to Scapa Flow and Rosyth where Beatty’s battle-cruisers were based, which would allow them to be in a more favourable position to intercept the raiders than had been the case during the Yarmouth raid.

The advent of the introduction of wireless telegraphy to the Navy in the early 1900s opened up the possibility of instant communication between ships and their home ports, where instructions and reports of enemy ship movements that previously could only be transmitted by visual signal could now be instantly available to an admiral leading a squadron into battle, enabling him to make instant tactical decisions that could affect the outcome in his favour.

An area where the British excelled was that of intelligence and the dissemination of the data they had gained. At the outbreak of war, Sir Alfred Ewing, a former scientist, was appointed Controller of Intelligence at the Admiralty, with Commander Alasdair Denniston acting as his ADC. The centre of this intelligence-gathering network was located in Room 40, Old Building, at the Admiralty in Whitehall. The whole undertaking was overseen by the redoubtable Admiral Sir Reginald ‘Blinker’ Hall in his role as Director of Naval Intelligence (DNI), who had formerly served as captain of the battle-cruiser RMS Queen Mary, but was forced to give up seagoing duties due to ill health.

As an officer of outstanding intellect and organising ability, Hall was offered the post of DNI, taking over from Captain Oliver, and quickly set up a highly efficient code-breaking and intercept service, establishing links with other British intelligence services such as MI5, MI6 and Scotland Yard.

Throughout the war a team of specialised cryptographers, drawn from a wide variety of civilian and service backgrounds, worked tirelessly on wireless code intercepts of German military and naval traffic, together with telephone and commercial cable traffic and other information garnered from neutral sources, commercial and business sources, and information supplied by spies.

By itself this information, randomly gathered, meant very little, but in the hands of the Admiralty cipher experts each piece was made to fit the complicated jigsaw that helped to understand the military and naval intentions of the Central Powers.

In this they were aided by an approach in the autumn of 1914 to the First Lord Winston Churchill by two English wireless amateurs: Barrister Russell Clarke and Colonel Richard Hippisley.

They informed him that, using their own private civilian equipment, they had for some time been picking up German military and naval wireless traffic and that these intercepts included wireless bearings issued to Zeppelin airships in the air and warships at sea. Recognising the significance of this information, Churchill immediately installed the two men at a remote coastguard station near Hunstanton on the Wash to listen in on the German frequencies.

A further refinement was added in February 1915 when, following successful wireless direction-finding experiments on the Western Front by the Marconi Company, Admiral Hall ordered the establishment of a further fourteen listening stations sited from Dover to the Humber and staffed by hand-picked GPO personnel. These stations were equipped with the latest equipment capable of taking cross-bearings on Zeppelin airships or surface warships as they approached the British coast and accurately pinpointed their locations.

In contrast, the Germans and their allies paid scant heed to the requirements of an effective military or naval intelligence service to aid their fighting services throughout the war. Their own efforts in this field were fragmentary and lacking a single, unified central department for sifting the large amount of varied information they received. The German High Command failed to appreciate the value of the information available to the British military and naval command and little realised to what extent their own efforts were being compromised by the highly efficient British secret service and the untiring work of the skilful analysts of Room 40.

The Admiralty cryptographers had a further advantage over their German counterparts, when in August 1914 the German light cruiser SMS Magdeburg was sunk by Russian cruisers in an engagement in the Gulf of Finland. Russian divers were subsequently able to dive on the wreck and recovered a haul of secret German naval codebooks and maps, which included the SKM code that was the main cipher then in use.

In an uncharacteristic spirit of co-operation on the part of the Russians, these codebooks were immediately dispatched to the Admiralty in London, arriving on the desk of Admiral Sir Reginald Hall, chief of naval intelligence in Room 40. These codebooks and others, such as the GN and VB codes, similarly retrieved from the German destroyer T119 that had been sunk at the Dogger Bank action, gave valuable insights into not only the current codes but also the system employed in the construction of new codes. This piece of good fortune allowed the Admiralty to read almost all German wireless traffic throughout the whole course of the war.

Another code that fell into British hands early in the war was the Handelsschiffsverkehrsbuch, or HVB code, which was the standard German merchant service code book, long compromised by British intelligence, the first copy of which was seized from an interned German merchant ship in Australia. This particular code was also used by the German Naval Airship Service where, due to an oversight of German security, Zeppelins departing their bases would transmit the message ‘Only HVB on board’, which meant that the more secret code books had been left behind, which in turn indicated to the code breakers of Room 40 that the destination of the airships was to be a raid on the British Isles, giving time for appropriate defensive countermeasures to be taken.

In December 1914 naval intelligence became aware through coded wireless intercepts of a planned sortie by units of the German High Seas Fleet. Accordingly, at noon on 15 December the 1st Battle-Cruiser Squadron under Admiral Beatty in his flagship Lion rendezvoused off the Scottish coast, with the 2nd Battle Squadron comprising the battleships HMS King George V, HMS Ajax, HMS Centurion, HMS Orion, HMS Monarch and HMS Conqueror, together with the 3rd Cruiser Squadron from Rosyth and attendant destroyers. The whole fleet was under the overall command of Admiral Warrender. At 3.00 p.m. the combined fleet moved southward to take up a position to the south of the Dogger Bank where they expected to meet and engage the German ships.

To the south, the Harwich Force, under Commodore Tyrwhitt, with the light cruisers HMS Aurora and HMS Undaunted leading forty destroyers, was ordered to sea, while Commodore Keyes departed Dover with eight submarines and two destroyers to patrol off Terschelling and intercept any attempt by the German ships to enter the English Channel. As a further precaution, Admiral Jellicoe dispatched four armoured cruisers of the 3rd Cruiser Squadron stationed at Rosyth to bolster the defending force in the event that more powerful German units accompanied the raid.

The German forces were led by Admiral Hipper, leading his 1st Scouting Group, including the battle-cruisers Seydlitz, Moltke, Von der Tann and Derfflinger and the armoured cruiser Blucher, together with light cruisers of the 2nd Scouting Squadron. Hipper headed west across the North Sea at high speed towards the British coast.

Following some miles behind, Admiral von Ingenohl directed his course towards the south of the Dogger Bank, where he intended to lay in wait with his battleships, as well as being able to protect the returning battle-cruisers and hopefully overwhelm any pursuing British vessels.

At 5.20 a.m., just west of the Dogger Bank, the German light forces accompanying Hipper’s battle-cruisers came into contact with British destroyers and exchanged fire in thick weather. News of this contact was wirelessed to von Ingenohl, who reasoned that the destroyers could represent the screening forces of the British battle fleet and, having no idea what strength they might be and in accordance with the Kaiser’s orders not to risk the High Seas Fleet, he ordered his ships back to Wilhelmshaven at 5.45 p.m.

The chance of the two fleets meeting was now dashed, although some of Warrender’s ships pursued the German cruiser Roon for several hours, which enabled her to make her escape and led them away from the main German fleet retiring eastwards.

Meanwhile, Hipper’s battle-cruisers were unaware that the main fleet had put back and that they now did not have the support of the heavy ships as they raced on towards the English coast.

At 8.00 a.m. on the morning of 16 December, in heavy weather that reduced visibility, the German battle-cruisers were standing off Hartlepool and Scarborough and began to shell the two towns, causing considerable damage. Over 1,100 heavy shells were fired by the attacking ships, with 300 houses being hit along with damage to the steel works, gasworks and railway, resulting in eighty-six people killed and up to 424 wounded. The scale of the destruction was unprecedented, and the sense of total shock to the survivors, many of whom had fled the attack to the surrounding countryside, fearing it was an actual invasion, caused panic along the coast.

In Hartlepool harbour, the light cruiser HMS Patrol put to sea only to be hit by two 8in shells, and on taking water was run aground by her captain to save her from sinking.

Hartlepool was defended by three 6in guns, which opened up on the raiders, causing some slight damage to the Seydlitz and Derfflinger and disabling two 6in guns on the Blucher while the attackers were briefly engaged ineffectively by a small force of destroyers.

After shelling Scarborough, the attacking force of three ships ran south to pour a rain of shells into the fishing port of Whitby before both groups reversed course to head home again at high speed.

Coming down from the north, Beatty’s cruisers came upon the German light cruisers scouting ahead of the main fleet and an indecisive, confused action followed until they were lost in the mist. At around 1.45 p.m. Beatty turned north, where, unbeknown to him, Hipper’s ships were on a converging course. But, on receiving an erroneous signal that the German ships had turned south, he turned his ships away to the south, allowing Hipper to escape.

Admiral Warrender finally called off the search at 4.00 p.m. on 16 December, turning his ship on course for harbour, disappointed that he had failed to bring under his guns the German fleet. Meanwhile, at Scapa Flow reports received at 1.50 p.m. indicated that the German High Seas Fleet was now at sea some 70 nautical miles north-west of Heligoland.

Fearing that they were planning to fall upon Beatty’s battle-cruiser squadron, Admiral Jellicoe ordered the entire Grand Fleet to sea. Pounding southwards in misty weather, the Grand Fleet rendezvoused with Beatty’s ships, but by that time the German ships were long gone.

British opinion was outraged by the flagrant disregard of the laws of civilised warfare shown by the German ships in bombarding the undefended towns of Scarborough and Whitby, which under the Hague Convention of 1899 were deemed immune from attack, while Hartlepool, with its three 6in guns, was considered a ‘defended place’ and as such a legitimate target. To the British public, however, with fresh accounts of recent atrocities and the shooting of civilians in Belgium, this was yet another example of ‘Hun frightfulness’.

Once again, the seeming ease with which the German ships had carried out their attack and returned safely to port almost unmolested by the Royal Navy, called into question the whole policy of the defence of Britain’s islands, a failure made all the more unpalatable by the fact that the Admiralty had prior warning of the raid and yet failed to respond effectively. Churchill demanded answers.

Following the seemingly successful and almost uncontested raids on the British coast in 1914, the Admiralty strengthened and increased the cruiser and destroyer patrols in the southern North Sea and the English Channel, with additional ships deployed to Admiral Tyrwhitt’s Harwich Force.

On the German side, von Ingenohl was anxious to repeat this form of attack in order, as before, to entice British ships into a well-laid trap; an eventuality he was planning for.

However, despite the loss of the cruiser Blucher and the severe damage sustained to Sheer’s flagship Seydlitz at the Dogger Bank battle in January 1915,where, due to poor communications and misunderstood orders between Beatty’s ships, the German ships were allowed to escape from a position where they should have been destroyed, the German Admiralty were dertermined to pursue the policy of coastal raiding.

The Kaiser was furious at the loss of the Blucher and the hazarding of his precious ships, and as a result von Ingenohl was replaced in February 1915 by Admiral Hugo von Pohl. Von Pohl more closely followed the Kaiser’s views of not hazarding the fleet on such risky ventures and saw the need to preserve the fleet in being by transferring a portion of the fleet through the Kiel Canal to the somewhat safer waters of the Baltic, and to a large extent ceding the control of the North Sea to the Royal Navy. He was, however, a sick man and dying of cancer, being forced to step down in favour of Admiral Scheer, who now became Commander-in-Chief of the High Seas Fleet. Scheer had for some time militated for a more offensive position to be taken on the employment of the fleet. Great Yarmouth and Lowestoft were again the targets selected for attack.

Lowestoft was the main British base for mine-laying activities, while Great Yarmouth was the centre of submarine activity in the southern North Sea and the English Channel, where they both contributed considerably to damaging and reducing German coastwise trade, so if severe damage could be done to either warships in harbour or harbour installations and workshops it would materially assist the enemy war effort and disrupt the British.

The date of the raid, 25 April 1916, was chosen to coincide with the Easter Uprising of Irish nationalists that had broken out the day before. Earlier German help had been sought by the rebel groups, the Irish Republican Brotherhood and the volunteers, and shipments of rifles and ammunition were secretly landed around the Irish coast in the preceding months from coasters and yachts to arm the dissident groups. A notable rebel leader was Sir Roger Casement, who had landed from a U-boat in Tralee Bay to co-ordinate the rebellion, but was captured almost immediately and subsequently executed by firing squad for treason.

On 23 April, German intelligence had reports of two separate light units of the Royal Navy operating independently off the Norwegian coast and in the Hoofden off the Dutch coast. Taking advantage of this disposition of British ships, Scheer planned to strike at the two harbours, which would attract these forces to their line of retreat, where the battle-cruisers would engage whichever of the two hopefully inferior forces first crossed their path.

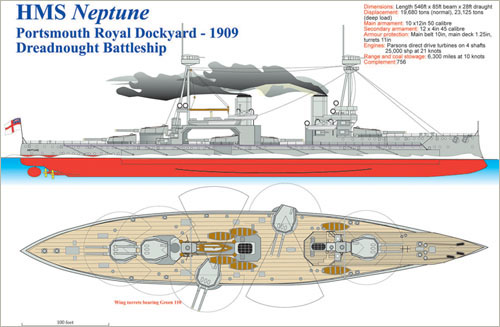

Fortunately for the Germans, and unbeknown to them, three ships of the northern force – the battle-cruisers Australia, HMS New Zealand and the battleship Neptune – had been involved in collisions due to fog off the Danish coast and had abandoned their operation and returned to port.

A feature of the raid was the inclusion of eight Zeppelin airships, under the command of Fregattenkapitan Peter Strasser, leader of Naval Airships, which, while operating independently of the fleet intending to raid the Midlands, provided a limited reconnaissance function that augmented the light cruiser screen, with their reports being available to Admiral Scheer by wireless as they flew westward.

The German battle-cruisers sailed from the Jade Basin mid-morning of the 24 April, followed by the battleship squadrons some 2 hours later, and escorted into the German Bight by the Zeppelin L7 cruising ahead of the fleet. At 2.30 p.m. the Seydlitz struck a mine off the home island of Norderney. She was seriously damaged with a 50ft hole on her starboard side, took on over 1,000 tons of water and suffered eleven crewmen killed. Initially it was thought she had been torpedoed, but the L7 flying overhead saw no torpedo tracks and escorted the badly damaged battle-cruiser back to Wilhelmshaven.

The new commander of the battle-cruiser fleet, Admiral Bodicker, transferred his flag from the Seydlitz to the Lutzow and, in order to avoid more minefields, sailed close to the West Frisian Islands, even though there was now a greater chance of his ships being sighted from the Dutch islands and reported to the British.

At 7.30 p.m. the Grand Fleet was ordered to weigh anchor and sail south, while at midnight Tyrwhitt’s Harwich Force put to sea with three light cruisers and eighteen destroyers heading north. Admiral Beatty’s battle-cruiser fleet had already put to sea from Rosyth and was battling heavy seas southward,100 miles ahead of Jellicoe’s battleships. At 3.50 a.m. the cruiser SMS Rostock of the scouting group sighted Tyrwhitt’s Harwich Force, which in turn reported four battle-cruisers and six light cruisers to the Grand Fleet racing southward at high speed.

The German ships reached the British coast and opened fire on Lowestoft at 4.10 a.m. While only lasting 10 minutes, the barrage sent a storm of high explosive shells into the town, destroying almost 200 houses, two gun batteries and fortunately only killing three civilians and wounding fifteen. The German ships then moved up the coast to Great Yarmouth, where a dense fog made the target difficult to observe and made only a limited practice before they retired to join the light cruisers that had been in action with Tyrwhitt’s ships to the south, causing serious damage to the cruiser Conquest and the accompanying destroyer HMS Laertes. Bodicker did not pursue the retreating British ships, as he feared they might be leading them into a trap, so he turned away to the north-east to rendezvous with the battle fleet off Terschelling.

Tyrwhitt’s squadron followed the German ships in heavy seas until ordered to turn back at 8.30 a.m. Similarly, the units of the Grand Fleet, fighting heavy seas that had caused their escorting destroyers to fall behind, was also instructed to abandon the chase at 11.00 a.m., when they were still 150 miles behind the battle-cruiser force. The rival battle-cruiser squadrons had in fact come within 50 miles of each other but, due to the poor weather and confused reporting of the disposition of various units, had failed to meet.

The German ships regained their harbours without further incident and the Germans could reflect that the raid had been a failure and achieved very little, with the Seydlitz mined, one U-boat sunk and another captured when it ran aground. None of the objectives of causing heavy damage to the harbour installations that would disrupt the mine-laying operations or curbing submarine activity in the two ports had been achieved.

Once again public outrage was expressed on this further attack on civilian targets and the Germans were regarded in neutral world opinion to have behaved in a barbaric fashion. In the United States in particular opinion hardened against them and their war aims.

Following these events, the 3rd Battle Squadron that previously had been part of the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow was moved down to the Thames and stationed at Sheerness to reinforce the Harwich Force.