At the outbreak of war the British Expeditionary Force, consisting of four army corps comprising six divisions of infantry, five brigades of cavalry and artillery, totalling some 150,000 men and everything necessary to support the army in the field, under the command of Sir John French and his general staff, was safely transported across the southern North Sea to France by the Royal Navy between 11 and 21 August without any loss to or interference from the German Navy.

The speed and efficiency with which the British movement of troops to the continent had been accomplished took the German high command by surprise, as they had assumed Britain would take much longer in mobilising her land forces.The British Army was in fact following a long-established War Office plan, formulated by Lord Haldane in concert with their French counterparts some years prior to the war, for the rapid deployment of British troops in the event of conflict with Germany.

The troopships were strongly protected by destroyer and cruiser flotillas and included aerial surveillance by two naval airships over the route, which deterred any interference from German torpedo boats or submarines.

Following the initial reverses suffered by the British and Allied armies through August 1914, with the retreat from Mons and the Battle of Le Cateau where the British at brigade strength faced whole German divisions, the Allies fell back toward Paris and faced defeat. The tide turned, however, at the ‘Miracle of the Marne’, when the British and French threw von Kluck’s army back at the beginning of September and then rapidly advanced northward to the River Aisne.

Here the war of movement came to a halt as the struggle inexorably settled into the trench warfare that was to characterise the four-year war. Under these circumstances the Government turned to the Royal Navy to strike an inspirational blow against the enemy that would boost public confidence and demonstrate Britain’s command of the seas, in keeping with its historic record of over 500 years of unchallenged naval ascendancy.

In early October 1914 the Fleet Commander Admiral Jellicoe communicated a memorandum to the Admiralty in which he expressed his contention that, in the event of meeting the High Seas Fleet in battle, the enemy would contrive that such an action would take place near to their home ports in the eastern portion of the North Sea, and that they would in all probability refuse to accept direct action, instead turning away with the intention of drawing the British ships into prepared minefields and ambuscades of torpedo boats and submarines.

Under these circumstances, Jellicoe stated that he would not pursue the enemy ships into their home waters, which he perceived would hazard his ships disproportionately due to the new threats posed by the mine and torpedo. This was a complete reversal of policy from the accepted battle instructions, which were based on the close pursuit and destruction of an enemy as the primary purpose of the fleet.Plans to carry the war against the enemy at this early stage were formulated and submitted to the Admiralty by Commodore Tyrwhitt, commanding the destroyer force at Harwich, who on their forays into the German Bight had observed a repetitive pattern of patrol by the German ships, where each evening destroyer flotillas would be escorted out by cruisers to patrol deeper into the North Sea and escorted back again in the morning.

Such a formation, comprising relatively lightly armed enemy warships, posed a tempting target. Despite the chosen scene of action being in dangerous proximity to the island of Heligoland, it promised the opportunity to wreak havoc among the lightly protected German ships. An emphatic British victory would do much to restore the morale of the British public following the setbacks in the land war in France referred to earlier.

The attack would have to be made as a lightning strike, quickly destroying as many German torpedo boats, and hopefully also light cruisers, as possible before the enemy could send heavier units from the Jade Basin in support. Tyrwhitt proposed the dispatch of a strong force of cruisers and destroyers in conjunction with Commodore Keyes’ submarine force, based at Dover, which would intercept the returning ships at first light and overwhelm them.

The plan was enthusiastically endorsed by First Lord Winston Churchill, who was delighted by the audacity of the plan in keeping with the offensive Nelsonian spirit of the Royal Navy. While he recognised the dangers of implementing such an attack by pushing so deep into enemy waters, he considered that a successful raid into Germany’s backyard would reap benefits in terms of an increase of prestige in the eyes of neutral opinion and a much needed boost to public morale at home.

In order to strengthen the raiding squadron, Churchill initially requested the additional support of the 2nd Battle-Cruiser Squadron, comprising New Zealand and Invincible under Admiral Moore, to be stationed some 40 miles to the west of the proposed scene of action, together with Cruiser force ‘C’ of five armoured cruisers Cressy, Bacchante, Hogue, Aboukir, and Euryalus a further 100 miles westward.

The submarine force consisted of the E class submarines E4, E5 and E9 accompanying the attacking force, while E6, E7 and E8 took station on the surface 3 nautical miles to the west of the planned battle area to entice the German ships out to sea and under the guns of the cruisers. Two further older submarines, D2 and D8, were ordered to close the Ems estuary and watch for any sign of reinforcements being sent to the German destroyers’ aid.

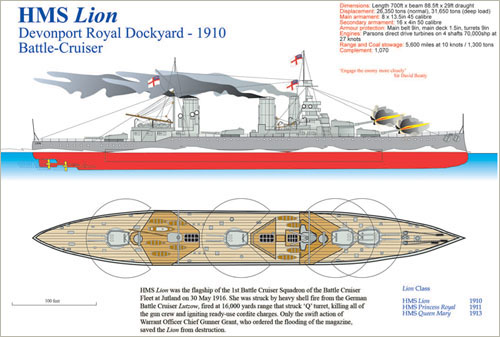

Before the sortie, planned to take place on 26 August, was sanctioned by the Admiralty, Admiral Jellicoe was concerned that in being so close to the German bases the hunters could become the hunted and therefore requested additional powerful support for the venture in the shape of three more battle-cruisers, Lion, Princess Royal and the Queen Mary, led by Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty.

Also included were the ships of the 1st Light Cruiser Squadron from Rosyth, with Admiral Goodenough leading in the 5,400-ton 6in cruiser HMS Southampton, accompanied by HMS Liverpool, HMS Birmingham, HMS Falmouth, HMS Lowestoft and HMS Nottingham, where, once agreed to by the Admiralty, the ships steamed southward through the night to the rendezvous.

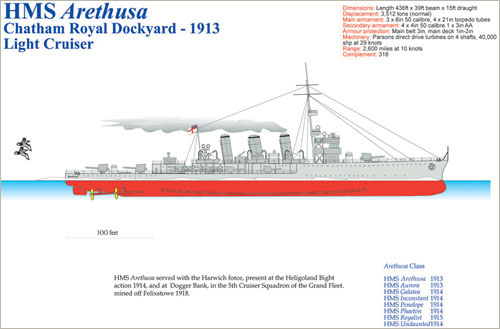

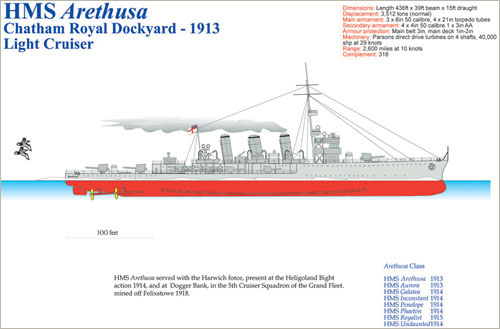

Jellicoe wirelessed a signal to both Tyrwhitt and Keyes informing them of the reinforcements but, due to delay in forwarding the message, neither were aware of the extra support available until they saw Goodenough’s ships emerging from the mist later in the action, causing some concern before they could be identified as friendly. At 7.00 a.m. on the morning of 26 August, in misty conditions, the Arethusa, leading a force of sixteen destroyers of the 3rd Flotilla, steaming at high speed in a position 12 miles north-west of Heligoland, sighted the German torpedo boat G194.

The British ships were followed at a distance of 2 nautical miles by the 1st Destroyer Flotilla, also composed of sixteen destroyers, with Goodenough’s six light cruisers a further 8 miles behind them. The deteriorating weather favoured the enemy – due to fog and misty conditions, visibility was only of the order of 2½ miles.

On sighting the British ships, the G194 reversed course towards Heligoland, working up to 34 knots, at the same time reporting the British presence to the commander of the torpedo boat flotilla, who passed the information on to Rear Admiral Franz Hipper, who was commanding the battle-cruisers in the Jade Basin. Here, due to the shallow waters of the anchorage, the battleships would have to wait until high water before they could negotiate the narrow channels and the bar at the mouth of the estuary leading to the open sea.

Admiral Hipper, assuming that the attacking ships only included two destroyer flotillas, ordered the light cruisers SMS Stettin and SMS Frauenlob – each armed with ten 4.1in guns – as well as six other light cruisers, the Stralsund, Strassburg, Koln, Ariadne and Kolberg, moored in the River Jade, and Mainz at anchor on the River Ems to raise steam and put to sea as soon as possible.

Off Heligoland, four of Tyrwhitt’s destroyers went in pursuit of the G194, opening fire on her and the rest of her flotilla when they were occasionally revealed to the British rangefinders through the encroaching mist.

Arethusa and her attendant destroyers began to overhaul the retreating Germans, opening fire at 8,000yd. Hits were registered on the torpedo boat V1 and two other torpedo boats, which requested the coastal batteries on Heligoland to lay fire on the British ships. However, the German gunlayers were unable to identify friend from foe in the fog and held their fire.

At 07.27 a.m. the British destroyers sighted and gave chase to a further force of ten German torpedo boats of the reconnaissance group, steaming at high speed towards the island of Heligoland. After chasing them for 30 minutes and coming within 2 miles of the island, where they found themselves being engaged by the cruisers Stettin and Frauenlob coming rapidly up from the east, they were forced in turn to fall back on the support of the Fearless and Arethusa.

With the German torpedo boats now safe in the island’s harbour, the German cruisers turned south-west to engage Tyrwhitt’s destroyer flotillas, with the Frauenlob coming into action against the Arethusa and the two ships trading shots through the increasing mist, as they ran on parallel courses to the south.

Although more heavily armed than the German ship, the Arethusa, having only recently been commissioned, was mainly crewed by reservists and was experiencing machinery problems, with two of her smaller 4in guns inoperative. Trouble was also experienced with the training mechanisms of the 6in batteries. Under these circumstances the Frauenlob was able to lay down an accurate fire in the British ship, causing severe damage to the cruiser.

Despite these drawbacks, the Arethusa returned fire at close range, causing terrible damage to the German ship, until finally a 6in shell struck the bridge of the Frauenlob, killing the captain and the entire bridge crew. The ship had to turn away towards the security of her base in a badly damaged condition and make her way slowly towards Wilheimshaven. She was the first serious casualty of the engagement in the first major fleet action of the war.

By 8.00 a.m. Goodenough’s cruisers Nottingham and Lowestoft had arrived at the scene of action south-west of Heligoland, crossing the path of the fleeing German torpedo boat V187, which reversed course with the intention of slipping through the pursuing destroyers and escaping eastwards. In this she failed to break through and was quickly sunk. As the British destroyers attempted to rescue survivors by lowering boats, the Stettin appeared from the north-east opening fire, which caused the British to abandon the German survivors and the British sailors in the lifeboats.

Running on the surface was the British submarine E4, which fired a single torpedo at the Stettin. Unfortunately it missed its target and caused the alerted cruiser to attempt to ram the E4, which in turn submerged to escape. Upon resurfacing when safe to do so, with the battle having moved away, the submarine retrieved the British crewmen and put the German survivors into the lifeboats, equipping them with a compass to row to the nearby German coast, as the submarine was too small to take them all aboard.

Commodore Keyes coming into action with the Fearless and his destroyer flotilla, who was still unaware of the approach of the additional force of cruisers and battle-cruisers sent by Jellicoe, sighted two four-funnelled cruisers on his port bow that he took to be enemy ships and informed Invincible he was in contact with German cruisers. Fortunately, Keyes identified them as British ships and rejoined Tyrwhitt’s squadron, continuing their sweep.

The British submarines, likewise, had not been informed of the cruiser reinforcements and at 9.30 a.m. one of them fired two torpedoes at the Southampton, which fortunately missed, and the submarine was lucky to avoid being run down by the cruiser.

Admiral Tyrwhitt joined with Keyes and, sighting Stettin, briefly opened fire on her before she disappeared into the mists.

By 8.15 a.m., the British 12th Flotilla led by Fearless had turned to the south-west, attempting to draw the German light cruisers towards the battle-cruisers Invincible and New Zealand, while still being unaware of the additional three battle-cruisers added to the squadron by Jellicoe.

The destroyers engaged German torpedo boats, sinking the V167 and two others, while damaging several more with accurate fire.

Fearless and her destroyer flotilla at 10.15 a.m. had fallen in with the Arethusa, which had been badly mauled and needed assistance with temporary repairs to her boiler room before she could proceed.

By this time, as reports of the action were received in Wilhelmshaven, Admiral Mass aboard his flagship the cruiser Koln, although still unaware of the scale of the attack and accurate whereabouts of the British ships, ordered to sea the cruisers Köln and Strassburg, modern ships both of 4,500 tons mounting twelve 4.1in guns, together with the smaller Ariadne armed with ten 4.1in guns, while the Mainz, also armed with twelve 4.1in guns, was coming up from the south-east.

The Strassburg came upon the damaged Arethusa heading south-west and attacked her with shellfire and torpedoes, but was herself forced to turn away thanks to heavy shellfire and determined torpedo attacks from the accompanying British destroyers.

By 11.00 a.m. Tyrwhitt’s flotilla led by the Arethusa was running to the south-west pursued by the German cruisers Stettin and Ariadne, who were firing on the retreating ships and gradually gaining on the British squadron.

At the same time the Köln was coming up independently from the south-east to join the action, but was similarly repulsed by torpedo attacks and badly damaged by shellfire, causing her also to turn away to the south.

Admiral Tyrwhitt, leading the German ships towards the rendezvous, had wirelessed for immediate assistance from Beatty’s battle-cruisers, which at that time were 40 nautical miles to the north-east, with Admiral Goodenough’s armoured cruisers some miles ahead. Beatty ordered his ships to maximum speed as they plunged southward towards the sound of gunfire.

At 11.30 a.m. Tyrwhitt’s ships engaged the lone cruiser Mainz as it crossed their track, into which they poured a storm of shellfire and torpedo hits, in which they were joined by the arrival of Goodenough’s cruisers, who also opened fire on the unfortunate German ship – by now a mass of flame and in a sinking condition.British destroyers lowered boats and brought a destroyer alongside to take off survivors, after which her captain ordered her scuttled and she finally sank at 12.45 p.m.

To the west, at 12.30 p.m., Beatty’s five battle-cruisers came rushing into action, throwing up high, curling bow waves as their 13.5in and 12in guns sought out their targets in the misty conditions that still persisted.

At 12.45 p.m. Lion and Princess Royal opened fire at 7,800yd on the Koln, Stettin and Ariadne, scoring hits with the first salvoes and causing the German cruisers to abruptly reverse course to the east.

Closing the range to 7,000yd, Beatty’s battle-cruisers wreaked terrible havoc to the German ships and, to add to their discomfort, from the south the Fearless also engaged the Stettin and Köln simultaneously.

The German ships attempted to escape to the north but Beatty brought the battle-cruisers and Goodenough’s squadron around to the north-east and continued to punish the enemy ships.

Although grievously damaged, the Stettin managed to disengage from the action and escape to the north-east and finally gain the Jade Basin and safety. The Köln, bearing Admiral Mass, staggered away to the north-east, as she was continuously being hit by the heavy shells from Beatty’s battle-cruisers, reducing the vessel to a fire-ravaged wreck.

Yet, despite the terrible damage being inflicted, the German ship still attempted to return fire and the superior quality of her construction and watertight integrity of her hull to a comparable British cruiser enabled her to remain afloat longer.

Eventually, however, as the battle-cruiser’s squadron swept round in an arc to the west, heading homeward after a final barrage of heavy shellfire, the Köln rolled over, slipping beneath the waves at 1.35 p.m.

Now the cruisers Danzig and Stralsund cautiously approached the area as the British ships departed westward and attempted to pick up survivors, but had to withdraw when British submarines were sighted manoeuvring to attack.

Admiral Mass went down with his ship, and of the estimated 250 survivors in the water only one was eventually rescued two days later by a passing fishing boat.

The final loss of the day was the Ariadne, which had been furiously engaged not only by the battle-cruisers but by the armoured cruisers of Goodenough’s squadron, finally sinking at 3.00 p.m. and effectively bringing the battle to a close, as far as the British were concerned.

Meanwhile, in an effort to support the beleaguered German ships, as wireless reports came in of the nature of the attacking force, Admiral Pohl ordered the battle-cruisers to sea.

In the Jade Basin the tide had now risen sufficiently to allow heavier units to put to sea and the Moltke and Von der Tann steamed out at 2.10 p.m., followed at 3.10 p.m. by Rear Admiral Hipper with the Seydlitz. But by the time they reached the area south-west of Heligoland the British ships were long gone and the battle was over.

From the British point of view the battle was a comprehensive victory and on the surface seemed to represent an example of an action that had been carried out with meticulous planning and attention to detail, executed with traditional verve and the bulldog spirit the public expected from the senior service.

Yet the whole episode had been characterised by muddled planning, poor communications and signalling to an extent that hazarded the success of the operation, as in the case of the cruisers Nottingham and Lowestoft. Although present during the initial stages of the operation, they somehow managed (due to poor communications) to lose contact with the ensuing action and took no further part in a battle in which their 6in guns could have been employed to good effect.

Nonetheless, the Admiralty must bear a large proportion of the blame, as they failed to communicate to the commanders of the various elements involved an overall united plan of action, or even to inform, for instance, Commodore Tyrwhitt and Keyes that additional powerful units had been dispatched to assist and support him in the operation.

Commodore Keyes was disappointed that the opportunity for a greater success had been lost, as the additional cruisers had not been included from the outset in the plan that was proposed by Jellicoe but rejected by the Admiralty.

The Germans had fought bravely, but by bringing their ships into the action as individual units rather than in the squadron formation adopted by the British they put themselves at a disadvantage, as the British could bring a heavier weight of fire to bear on individual ships. That being said, German ships were class for class superior to their British counterparts and due to their strong construction and watertight integrity they were, despite severe punishment, hard to sink. On this occasion, however, their faster firing 4.1in guns were no match for the slower firing but heavier 6in guns of the British cruisers. They had lost three light cruisers, Mainz, Ariadne, Köln, and the cruiser Frauenlob was severely damaged, as were to a lesser extent the Strassburg and Stettin. The destroyer V187 and two other torpedo boats were also sunk and other torpedo boats and mine sweepers damaged.

The German casualities included 714 killed, including Rear Admiral Mass, and 336 captured as prisoners of war, while, although several Royal Navy ships were damaged, none had been lost and casualties were limited to thrity-five killed and forty wounded.

The effect on the Germans of this encounter was one of profound shock and it was a damaging blow to the morale of the High Seas Fleet. The immediate result was that the Kaiser ordered all future naval operations to be personally approved by him before being implemented.

Bad communications on the German side also had a bearing on the outcome of the battle, as the presence of the British cruisers had not been communicated to Admiral Hipper until as late as 2.35 p.m., by which time the British ships were retiring. Had Hipper been made aware earlier, his battle-cruisers could have created a very different outcome to the battle.

The daring nature of the raid, with the British risking their most powerful vessels so deep in enemy waters, deeply impressed the Germans. As Winston Churchill wrote in The World Crisis: ‘The British did not hesitate to hazard their greatest vessels and light craft in a most daring offensive action, and had escaped apparently unscathed.’ The Germans felt as the British would have done had German destroyers broken into the Solent and their battle-cruisers had penetrated as far as the Nab Tower.

To the logical German mind such an attack so close into their home waters, an area protected by minefields and submarines, with a battle squadron prepared to sail only an hour away, was utter madness and it was beyond their comprehension that it could have been countenanced by the Lords of the Admiralty. However, it only served to increase the respect in which they held the Royal Navy, as well as increasing the feeling of inferiority felt within their own fleet.

The immediate effect of the raid over the next months severely curtailed the patrolling of the German Bight by the torpedo-boat flotillas, with only the most essential mine-laying sorties to maintain the defensive mine barrages being carried out, together with limited scouting by the torpedo boats. During the years preceding the Great War, the German Navy had concentrated on building dreadnought battleships in an effort to maintain a sufficient number of these vessels to challenge the Royal Navy’s position. To achieve this end, vast amounts of the nation’s wealth was required to support the building programme, so that cruisers and other types of warship for the fleet were produced in lesser numbers than were required to create a balanced fleet.

The numbers of cruisers built from 1900 onwards were also below the figure that Admiral Tirpitz would have considered necessary to perform the varied scouting duties, fleet protection and distant patrol work for which they were designed. A unique alternative to perform the vital role of scouting ahead of the fleet and to provide the essential early warning to the fleet commander of the presence of an approaching enemy squadron could, it was asserted, be provided by the scouting airship.

An airship from its elevated vantage point flying at 3,000ft could scout a far greater area of ocean more rapidly than was possible from the deck of a cruiser, and could be built at the fraction of the cost of a surface ship.

Count Zeppelin’s first airship had flown over Lake Constance in July 1900 and in the intervening fourteen years had developed into a viable flying machine, first as a commercial carrier, then to be employed for war purposes, initially by the Army and later the Navy.

At the outbreak of war the German Army possessed ten airships, which they used to support their advancing troops by bombing frontier fortresses and strong points, but in doing so quickly lost three Zeppelins to ground fire.

Before the Great War there was a widely held belief amongst the British public that, in the event of war with Germany, fleets of giant Zeppelin airships would launch bombing attacks on major cities within hours of a declaration of war. Such attitudes had been encouraged during the years of mounting international tension by sensationalist writers of the day such as William le Queux, a novelist and self-styled secret agent. They were also influenced by the works of H.G. Wells. In his prophetic novel, The War in the Air of 1908, he describes how a German attack on the United States by a fleet of giant airships destroys the American Atlantic fleet and then obliterates New York, before they are, in turn, overwhelmed by a superior Asiatic air fleet, with the ensuing worldwide war leading to the breakdown of organised government and the total disintegration of civilised society.

In the event, at the outbreak of war the German Navy had only one Zeppelin in service, the L3 based at Fulhsbuttle near Hamburg, but by December 1914 it had been joined by five new airships numbered from L4 to L8 whose primary duty was to scout ahead of the High Seas Fleet.

The Committee for Imperial Defence prior to the war, when considering the protection of naval dockyards, forts and magazines, had decided that the Army would be responsible for all home defence matters. However, once the war had started, with all the existing army’s Royal Flying Corps squadrons quickly accounted for supporting the BEF in France, it was apparent that the task of supplying aircraft for home defence was beyond the capability of the War Office.

Accordingly, the responsibility for the aerial defence of the British mainland passed by default to the Royal Navy, with the army still maintaining the fixed-gun defences. At this stage of aeronautical progress the airship was considered to be almost invulnerable to attack and could easily out-climb the primitive aircraft available by dropping water ballast and ascending at a rate that left the aircraft standing.

Once again the First Lord Winston Churchill convened a conference to discuss how to deal with the Zeppelin menace.

In response to the news that the Germans had established airship bases in occupied Belgium, bringing the threat of an attack closer to the capital, the Admiralty proposed a bold plan to strike at the Zeppelin bases in Belgium and on the North Sea coasts, with the intention of destroying the airships before they could be used.

The first of these raids by aircraft of the Royal Naval Air Service based at Dunkirk was launched on 9 October 1914, when Commander Spencer Grey and Flight Lieutenant Marix, flying Sopwith Tabloid biplanes, set out to bomb the Zeppelin sheds at Cologne and Dusseldorf.

After a flight of 100 miles, Marix located the Dusseldorf shed and in the face of heavy machine-gun fire dropped his two 25lb bombs, scoring a direct hit and destroying the army Zeppelin Z9 inside. This was the first success of its kind by the Royal Naval Air Service. Meanwhile, Spencer Grey, frustrated by thick fog over Cologne and being unable to locate the sheds, dropped his bombs on the main railway station instead.

A further attack of an even more daring nature was carried out by the Royal Naval Air Service on 21 November 1914 from Belfort near the Alsace-French border. It was aimed at the very heart of the Zeppelin empire at Friedrichshafen. Early in the morning three Avro 504s, each carrying four 25lb bombs, flew 125 miles through the mountains on a route carefully designed to avoid Swiss territory to emerge on the south side of Lake Constance before climbing to attack the Zeppelin works.

British airmen claimed a direct hit on one of the main sheds; however, German sources to this day continue to claim that the raid caused no damage, although the testimonies of Swiss workers in the factory maintain that a partly built airship was destroyed.

A particularly audacious air raid was planned for Christmas Day 1914 to attack the airship shed at Cuxhaven and, simultaneously, attack warships at anchor at Wilhelmshaven. Commodore Tyrwhitt again led the Harwich Force of three light cruisers and a destroyer flotilla of eight ships and supporting submarines under the command of Commodore Keyes, these submarines leaving port on the evening of the 24th to be in position off the German coast next morning. Further support was supplied by the 1st Battle Squadron under Sir David Beatty, led by Marlborough and seven other dreadnoughts, together with the 6th Cruiser Squadron being ordered south to Rosyth from Scapa Flow on 21 December.

Accompanying the Harwich Force were three fast cross-channel steamers, Empress, Engadine, and Riviera, that had been converted as seaplane carriers, each carrying three Short type 74 or type 81 seaplanes with folding wings that allowed them to be stored in the hangers aft. The three seaplane carriers departed Harwich at 5.00 a.m., followed at intervals by the Harwich Force, reaching the launching point for the seaplanes 40 nautical miles north-west of Cuxhaven at 6.00 a.m. on the morning of 25 December.

Amazingly, the seaplane carriers had reached the rendezvous point undetected and, coming to a halt, lowered the nine planes, each armed with three 25lb bombs, onto the calm water.

The engines of two of the machines failed to start and they were hoisted back aboard, with the remaining seven machines taking off from the smooth water at 7.00 a.m., climbing slowly as they headed eastwards towards Cuxhaven and Wilhelmshaven – the main targets of the raid.

Although the weather was clear over the sea, on reaching the coast the British aircraft encountered a thick fog bank reaching far inland, which made it impossible to locate the main target, the Zeppelin shed. Instead, the aircraft attacked what targets they could find, with flight commander Hewlett attacking a destroyer at 8.20 a.m. and flight commander Oliver attacking the seaplane base on Langeoog Island, while Flight Lieutenant Edmonds attacked the cruisers Stralsund and Graudenz in the Jade Estuary.

Lieutenant Erskine Childers, author of the novel The Riddle of the Sands, which was set in these very waters, was an observer in one of the machines that reconnoitred the Schillig Roads, identifying several dreadnoughts and heavy cruisers.

At the Zeppelin base of Nordholz near Cuxhaven, two airships, the L6 with Kapitanleutnant Horst von Buttler Brandefels in command and the L5 under Kapitanleutnant Hirsch, had taken off at 6.00 a.m. on a reconnaissance of the waters beyond Heligoland.

As a clear dawn was breaking on a north-westerly course, L6 steered over Heligoland, where, after an hour, three ships were spotted cruising slowly to the north-east. Von Buttler Brandenfels identified these as minelayers and was preparing to wireless the discovery to base when the wireless set went dead. Fortunately for them, a German seaplane came up on their port side and they were able to relay the warning by signal lamp for it to be sent on to Wilhelmshaven.

The L6 had arrived after the seaplanes had departed so had no idea of the true purpose of the operation, but on seeing more British ships, cruisers among them, von Buttler Brandefels took his airship lower and dropped three bombs on one of the carriers, all of which missed.

Soon the L5, alerted by radio, appeared on the scene accompanied by German seaplanes, just as the British seaplanes were returning after almost 3 hours and were short of petrol. As they landed alongside the carriers to be recovered, they were subjected to bombing attacks, which were largely ineffectual and turned into a general melee of ships against aeroplanes and airships with no conclusive result, and tellingly no interference from German surface forces.

Only two aircraft were recovered and hoisted on board, the remainder landing short of the rendezvous, where the crews were picked up by British submarines and destroyers, while the aircraft were sunk to avoid them falling into enemy hands.

One pilot originally posted as missing was picked up by a Dutch fishing boat and eventually returned to England. Once all the naval flyers had been recovered, Commodore Tyrwhitt ordered the Harwich Force to withdraw, which it did at 11.45 a.m. without loss.

Although the raid failed to achieve its main objective, the destruction of the airship sheds demonstrated that the combined British surface and air arms had successfully carried out an operation that both demonstrated that the Royal Navy could operate with impunity deep into the enemy’s heartland and give a much needed boost to morale at home once news of the raid was made public.