Chapter Seven

Inside Out

With her songs “Lucky Star,” “Like a Virgin,” and “Material Girl,” pop star and actress Madonna owned the 1980s. Her unconventional sexual style both onstage and offstage infuriated the mainstream and earned her the condemnation of Pope John Paul II, head of the Roman Catholic Church. Yet Madonna’s music videos, concerts, and movies were wildly popular, and they brought women’s lingerie out of the bedroom and fully into high fashion.

You Must Be My Lucky Star

Capri pants under short skirts.

Black rubber bracelets from wrist to forearm.

Earrings and necklaces with chunky rhinestone-studded crosses.

Torn mesh shirts over black lace bras.

In the 1985 movie Desperately Seeking Susan, Madonna plays Susan, a New York City woman who pulls bored suburbanite Roberta, played by Rosanna Arquette, into her bohemian lifestyle. In one scene, Madonna wears a white garter belt and lace stockings over a pair of shorts. In another, she sports a black lace crop top that clearly shows off the bra underneath. Because of Madonna, exposed bras, corsets, garters, and stockings became key elements of a new look.

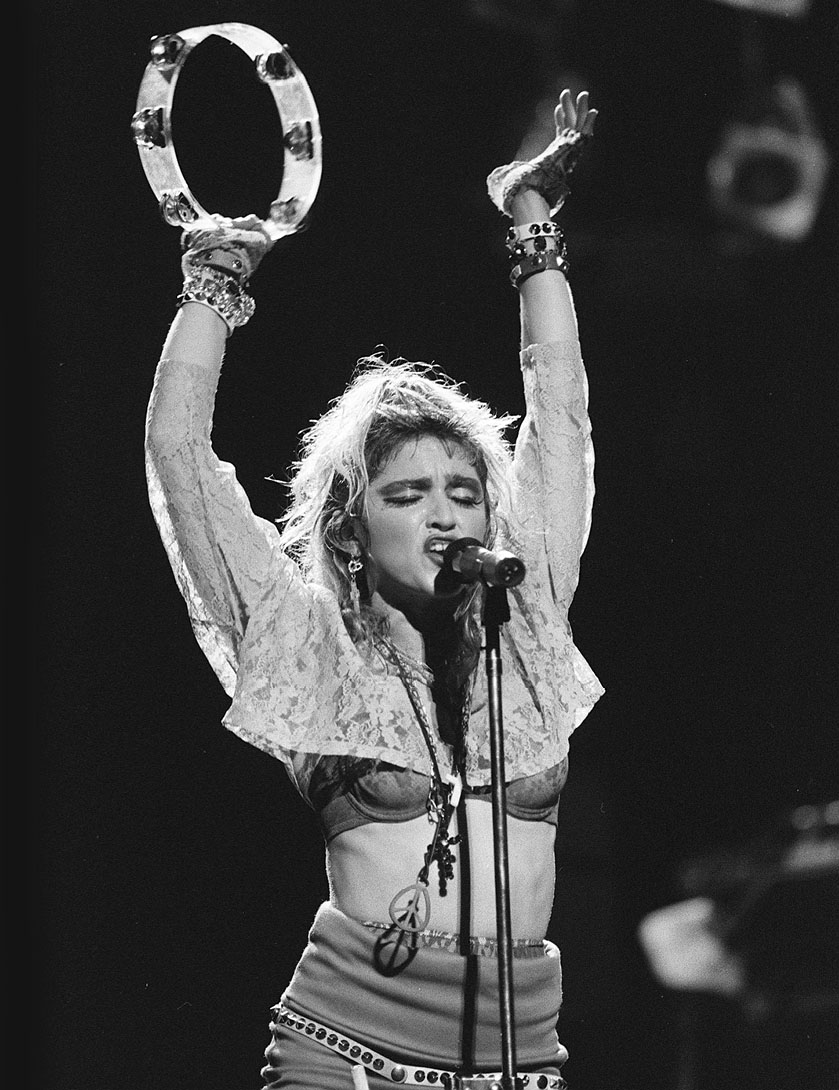

Madonna rocketed to stardom in the mid-1980s with the film Desperately Seeking Susan and her first concert tour (the Virgin Tour). Underwear as outerwear was her signature look in stage concerts such as this one in 1985.

Madonna wore lingerie in her stage shows too. Her clothes and her sexually charged performances brought female sexuality and rebellion out into the open. She wasn’t hinting at sexuality or being subtly subversive. Instead, Madonna yelled her rejection of feminine social norms.

For the Blond Ambition World Tour in 1990, Madonna wore a pale pink, one-piece belted corset with a front zipper from crotch to cleavage and a pink garter belt with black stockings. The corset’s exaggerated breast cups were large and conical, with in-your-face protruding points. French high-fashion designer Jean Paul Gaultier, who designed the outfit, was inspired by the bullet bras of the 1950s. The garment connects historically confining lingerie with modern eroticism and female power by merging soft pastel pink with aggressive lines.

Madonna’s 1990 “Vogue” music video evokes the Hollywood glamour and style of the past through images and lyrics that recall stars such as Marilyn Monroe, Jean Harlow, Greta Garbo, Ginger Rogers, Rita Hayworth, and Bette Davis. In the video, Madonna makes many costume changes, including a see-through camisole, an exaggerated velvet cone bra, and a re-creation of the Mainbocher corset made famous by photographer Horst P. Horst in the 1930s.

“Vogue” was not only about fashion and lingerie. It also challenged gender and sexual identity norms, featuring acrobatic voguing, a dance form that emulates model-like poses from fashion magazines. Voguing originated in the 1960s in the gay nightclub scene of New York’s Harlem neighborhood, particularly among black and Latino drag performers. Madonna hired some of these gender-bending dancers for her video, which brought mainstream attention to the dance style. Madonna’s video was openly admiring of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning (LGBTQ) style, which made its way into haute couture (high fashion).

Haute Couture

Gaultier isn’t the only designer to use lingerie front and center in high fashion collections. Corsets have inspired the work of John Galliano, Karl Lagerfeld, Tom Ford, Gianni Versace, Valentino, Vivienne Westwood, Issey Miyake, Hussein Chalayan, Alexander McQueen, Christian Lacroix, and Thierry Mugler. These designers use visible corsetry to express a wide range of ideas about women, femininity, power, sexuality, and gender identity.

Corset-inspired creations by French fashion designer Thierry Mugler, for example, are far more than just garments. His works combine soft fabrics with hard materials such as leather, Plexiglas, and metal to encase the female body. When wearing these corsets, a model is transformed into a mythic Amazon, an armored knight, a biker, a robot, an alien, or an insect. Mugler’s fierce fashions evoke strong reactions. Some are offended by his fetish-inspired designs. Some are shocked by garments that seem almost like an act of violence against the model’s body. Others see his work as transformative, elevating the female form to something more than human.

Beyoncé and high-fashion designer Thierry Mugler have collaborated on many of the megastar’s stage shows. Mugler says he designs her costumes, many of which use lingerie as the foundational garments, to be “Feminine. Free. Warrior. Fierce.”

In 2008 pop sensation Beyoncé attended an event at the Costume Institute Gala at the Metropolitan Museum in New York called Superheroes: Fashion and Fantasy. The exhibition paired actual costumes from superhero movies with pieces by famous designers. One of Mugler’s corset designs, which drew on motorcycle parts, transformed a model into part-vehicle, part-human. Beyoncé was so impressed that she commissioned Mugler to design costumes for her United Kingdom tour. She also chose a powerful, sexy photograph of herself wearing a Mugler motorcycle corset for the liner notes of her 2008 album I Am . . . Sasha Fierce.

Queen Bey

On February 1, 2017, long after the motorcycle corset, Beyoncé posted a photo to Instagram to announce that she and husband, Jay Z, were expecting twins. In the photo, taken by Ethiopian American multimedia artist Awol Erizku, Beyoncé kneels against a profusion of flowers, with her hands on her pregnant belly. She is radiant, wearing only a pair of ruffled, blue silk underpants, a sheer maroon bra, and a pale green veil.

Scholars and fans immediately began to analyze the image. Artistically, Beyoncé’s portrait recalls the lush, colorful paintings of Frida Kahlo and Gustav Klimt. It also brings to mind the works of modern artists such as Kehinde Wiley and Mickalene Thomas, who feature people of color against bright, floral backgrounds. The intensely vivid colors of Beyoncé’s lingerie and the blissfully happy look on her face reminded many of the colorful Our Lady of Guadalupe (a Roman Catholic image of the Virgin Mary) in Mexico City.

In the photograph, Beyoncé stares right at the camera. Katie Edwards, the director of the Sheffield Institute for Interdisciplinary Biblical Studies in the United Kingdom, says Beyoncé’s look is an example of “the oppositional gaze.” Cultural critic bell hooks (who does not capitalize her name) coined this term in the early 1990s. Like the male gaze, the oppositional gaze is an idea from film theory. The male gaze, hooks says, is based on the notion of white women as the objects of sexual desire for heterosexual men. For black Americans, the gaze is more complex. Black Americans have historically faced severe punishment, even murder, for looking directly at white people. Looking is, therefore, a political act for people of color, hooks points out. She says, “All attempts to repress our/black peoples’ right to gaze had produced in us an overwhelming longing to look, a rebellious desire, an oppositional gaze.”

In Erizku’s photograph, Beyoncé offers her own oppositional gaze. She confronts racist stereotypes of women of color as sexually aggressive, primitive, and exotic. According to Edwards, this message is communicated specifically by Beyoncé’s choice to pair lingerie with religious imagery such as her veil (which is associated with the Virgin Mary) and kneeling posture. In the portrait—the most popular Instagram post of all time with more than eleven million likes—Beyoncé claims her sensuality, her personal power, and her maternal side. She is Queen Bey.

Protest and the Shattered Body

Beyoncé is not the only artist to use lingerie to make a statement about society and the female body. Since the 1960s, feminist artists have depicted undergarments in photographs, sculptures, paintings, and mixed media work. These pieces focus on the experiences of the female body—menstruation, sex, pregnancy, childbirth, assault, athleticism, aging, pleasure, and pain.

Barbara Kruger made the “Your Body Is a Battleground” poster (left) in 1991 to protest a series of court decisions that were chipping away at the constitutional right to abortion. Artist activists use artwork to protest other restrictions on women’s bodies, including undergarments.

Laura Jacobs sculpts three-dimensional female torsos. Each one is wearing undergarments—bras and panties, traditional corsets, or erotic fetish wear—made of shattered glass, tile, or shell. Each mosaic piece has an evocative, punning title such as Fertile Crescents or The Breast of Both Whorls. Jacobs’s website says of her work, “No longer bound by constraints of clothing alone, women may now have the delightful pleasure of deforming themselves from the inside out.”

Nancy Davidson uses giant latex balloons to create voluptuous hanging sculptures of breasts (that also double as eyes) in lacy bras. She also creates bulbous butt cheeks wearing frilly G-strings. One piece called Blue Moon is a huge blue balloon laced into a giant, white corset. The balloon bulges out at the top and bottom of the corset. About her own work, Davidson says, “You laugh at the enormous breasts, the big butt, and suddenly it’s like, ‘Oh my God, what am I laughing at, why is this sexual thing making me so uncomfortable?’ ”

Nancy Davidson uses latex, rope, and cotton to create her inflatable body sculptures. Her in-your-face-humor is meant to nudge viewers to think about the ways fashion forces bodies into random, often absurd shapes. This sculpture, called Blue Moon, features a body squeezing out of a giant, white corset.

Miriam Schaer’s work was inspired by medieval girdle books—prayer books that monks tied to their girdles (belts). She takes corsets and stiffens them until they are solid and unbending. She slits them open and then uses the two halves of the garment as the cover of a book. The book holds images and small items such as feathers or a multilayered Jewish Star of David. Schaer says, “The garment becomes immobile, as if the wearer evaporated, leaving only a shell. They [the corsets] become places. Enclosures. Upon opening, the ghost of the missing person still remains in the echo of the garment’s fixed shape.”

Musicians such as Madonna and Beyoncé and visual artists such as Jacobs, Davidson, and Schaer use women’s undergarments as social commentary. For them, a woman’s body has always been a battlefield.