• CHAPTER NINE •

TWICE A CANDIDATE

Abe Lincoln liked the appearance of his letter in the newspaper. But before he got his campaign under way, new and exciting news was brought to New Salem by a traveler from Beardstown, thirty miles to the west.

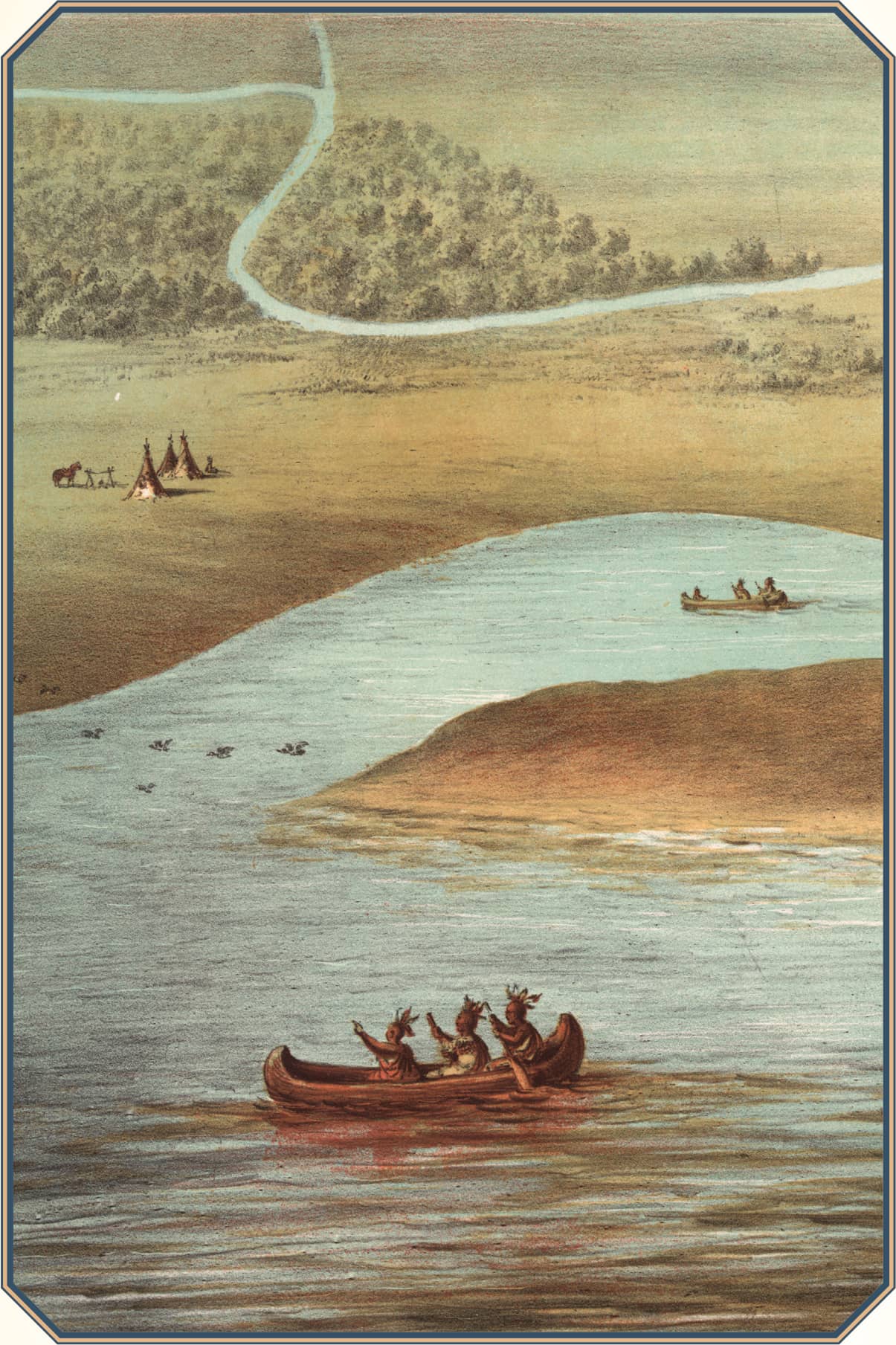

A mill owner, Vincent Bogue of Portland Landing, was coming up the Sangamon in a chartered steamer, the Talisman, with goods from Cincinnati. Now with New Salem on a commercial waterway, the long-hoped-for boom would come!

Chicago in 1820.

Soon Bogue and his steamboat arrived at Beardstown. He sent messengers to New Salem for workers. They were to meet his steamer at the mouth of the Sangamon and lop off overhanging branches that might harm the steamer’s paint. Abe Lincoln was hired as one of this gang.

When the Talisman steamed past New Salem, the bluff was packed with villagers eager to see the gleaming white and gold boat and to cheer as her twin stacks sent smoke drifting over the prairie. Many people went to share in a great celebration.

On April 5, 1832, Springfield’s newspaper, the Sangamo Journal, printed an account of this event and even a “poem” written in honor of the occasion. People quoted favorite lines:

If Jason who the golden fleece

Sailed for many years from Greece

To such a height of fame did get

The Argonaut’s remembered yet

Then what a debt of fame we owe

To him who on our Sangamo

First launched the steamer’s daring prow.

What think ye, laddie, isn’t it grand

To see a steamer touch our strand?

The cargo sold at a profit and the captain was entertained till someone noticed that the high water was gone. If he wanted to go back to Ohio, the captain had better go while he could still float his boat!

Bogue engaged Rowan Herndon and Abe Lincoln to help him steam down river and all was well till they came to the Rutledge Dam. No clever trick could get this big steamer over!

“We’ll have to remove part of your dam,” Herndon yelled.

“Ye ain’t allowed to touch it,” Rutledge shouted back.

“You daren’t obstruct a navigable river,” Abe Lincoln announced firmly. Rutledge was silenced, for he too, knew the law. He fumed while Herndon and Lincoln laboriously removed part of the dam, got the steamer over, and made the repairs required by law.

New Salem people watched sadly. Such difficulty, early in the season, showed that the Sangamon could not be depended on. The boom was over. That inglorious retreat of the Talisman marked the end of New Salem’s hopes of becoming a great city.

Lincoln walked back to the village expecting to find his friends discouraged. Instead they were excited about a war and the governor’s call for volunteers to settle a dispute with the Indians.

Abe Lincoln and about twenty-five others from New Salem enlisted and went to Richland to enter the service. Lincoln was gratified when the company selected him captain. This honor was more than leadership of a gang; it was an election that gave him a responsible job for his country.

He did his best to train his men for battle, but they had no chance to show their bravery. After the month ended, many went home. Lincoln decided to re-enlist. This time he was a private among strangers, and again he had no chance to fight; for the Sac Chief, Black Hawk, was taken prisoner and his people driven across the Mississippi. Soon Abe’s company was mustered out in southern Wisconsin, and men from Sangamon County walked home together.

On this journey Abe Lincoln became acquainted with John A. Stuart, a young attorney from Springfield. Stuart was a well-educated Kentucky aristocrat who had come to Illinois in 1828. He was a Whig and two years older than Lincoln; he practiced law in Springfield, had influence in the county, and was running for election to the State Legislature, as Lincoln was. Stuart liked Abe and encouraged him to study law and to run for the state office. As they tramped south the two men became friends, and Abe discovered that Stuart had what Abe wanted most—law books which he was willing to lend to a new friend.

The Black Hawk War was a minor event in national history but a major factor in Lincoln’s development. It brought him his first election, the captaincy, and introduced him to a man competent and willing to help him study law. His feeling that destiny sent him to New Salem had been right; in the year that he had lived there, he had attained leadership in his community, improved his education, and had found a lawyer friend who would help him.

His next step was to start his campaign. Election day was less than two weeks away.

Since the time was so short, Abe decided to make a direct appeal to the voters. At harvest time men got together for the auction of livestock, for cornhusking, and for other seasonal work; and they liked some political talk when the job was done. Lincoln’s first chance to speak came at an auction nearby. He arrived early, dressed in his best—a coat of mixed-jeans, cut claw-hammer fashion (with sleeves and coattails too short), tow-and-flax pantaloons, and a straw hat without a band. He visited with the men and made a campaign speech. His statement of principles got attention, and his backwoods tales delighted them. A favorite yarn was about a preacher who during a long sermon felt a lizard crawling up inside his breeches. Abe Lincoln’s gifted mimicry as he acted out the preacher’s frantic misery had the men rocking with laughter.

Chicago in 1820.

Encouraged by this modest success, Lincoln tramped from place to place around New Salem. Just before election day he went to Springfield for a meeting where all candidates spoke.

Lincoln lost the election; he stood eighth among the thirteen who contested. John Stuart was among the fortunate four who were elected. But, though he lost, Lincoln had profited by trying. He had learned to speak in public, he had made many friends, and—at the Springfield meeting—he had become acquainted with Stephen T. Logan, a prominent attorney. Like Stuart, Logan was a Whig from Kentucky. He was already considered one of the best lawyers in the state. Now Abe had two lawyer friends in Springfield.

“I didn’t do badly,” Abe Lincoln consoled himself. “If I had had more time I might have won.” He was proud that all but seven of the New Salem men had voted for him.

The campaign over, there was the matter of earning a living. Abe called on James Herndon, who with his brother Rowan had a store in New Salem, and asked for a job as a clerk.

“Me need a clerk?” Herndon growled. “Business is so bad that I’m more likely to sell out than to hire! This town has been dead since the steamboat line busted. But you’re welcome to live here, Abe, till you get settled.”

Soon James Herndon did sell out his half interest to a William Berry and Rowan sold his half to Lincoln, taking Abe’s promise in payment. So Lincoln, to his amazement, found himself a penniless half owner of a store under the name of the Lincoln-Berry Store. Of course there was a debt of several hundred dollars but that did not worry Lincoln—nor Herndon either, for he knew Abe was honest.

During the next few months (in late 1832 and early 1833) Lincoln had a comfortable life. He roomed back of the store, and had time to read and to enjoy his neighbors. The Rutledge tavern was just across the way. Ann often came in to buy for the family, and they talked about books and their ambitions. On Saturdays the store was full of customers.

During this time Abe Lincoln often went to Springfield to borrow books from Stuart or Logan and to talk with them about the books he returned. On one trip he chanced to hear of an auction in town. He strolled over, arriving as a copy of Blackstone’s Commentaries (a basic law book) was put up for sale. He bought it and stumbled all the way home as he tried to read and walk across the prairie!

But alas! Bill Berry’s carelessness and Lincoln’s devotion to reading did not help business. Women who came to buy found Bill asleep and Abe deep in Thomas Paine’s Age of Reason, good-humored enough but not much interested in matching thread or buttons. Few shared the owner’s surprise when the store failed. Soon after his twenty-fourth birthday Lincoln was jobless again and in debt. A few months later Berry died, leaving the whole sum for Abe to pay.

At that time, most men in such a situation simply left town and started over in a new place. But Abe Lincoln had a firm faith in himself and a conviction that he should stay in New Salem.

Friends got him a job as postmaster for the village, and he began work in May of 1833. This position gave him a place to stay, in Hill’s store, and a small income. Stamps were not yet used: the person who received a letter paid the fee. A single sheet cost six cents for thirty miles, twenty-five cents for four hundred miles. The postmaster kept thirty per cent of the fee and sent the remaining seventy per cent to the mail service.

Now, Abe could read incoming newspapers after the mail arrived each Saturday. He had a growing audience as he read aloud the Sangamo Journal, the Illinois State Register, and other papers.

He had further good fortune. Mentor Graham chanced to hear that the county surveyor was behind in his work since settlers were arriving daily. So Graham recommended Lincoln as an assistant.

“Abe is not informed in higher mathematics,” Graham admitted to Calhoun, the surveyor, “but if you can wait for six weeks, I think I can coach him for you.” Calhoun agreed to wait.

Now, again, Lincoln educated himself for a particular task. With Graham’s help, Abe studied days and evenings. In six weeks he bought a compass and surveyor’s chain and started work while he continued to study evenings. The surveyor was paid a fee for each piece of land surveyed. Abe’s share—plus small fees as postmaster—gave him a fair cash income, so he could pay board and also set aside something toward his debt. “You should forget that store debt,” friends told him.

“Surely you don’t owe for Berry’s share. He’s dead.”

“He was my partner,” Lincoln replied. “I’ll pay.” And he did pay—though it took many years of saving.

Abe Lincoln made many friends as he tramped the county with Calhoun. His tall, lanky figure and friendly smile were remembered. He was often asked questions about deeds or taxes or sales of lands. He answered those the best he could, and when he did not know, he looked for the answer in the Springfield libraries. One day he bought some legal forms so he could fill out papers for friends. He made no charge for this work of course. He was not licensed to practice law and his advice had no standing. But it was a kindly service, and it helped him educate himself.

Often a friend loaned him a horse and he combined his two jobs. He carried in his straw hat, letters or papers addressed to a farmer living far from the village.

“That’s mighty kind of you, Abe!” was his reward.

Motherly wives took an interest in him. “Abe, yer lookin’ kinda peaked,” one said.

“Abe’s fixin’ to be a lawyer,” her husband remarked. “He’s studyin’ nights.”

When Abe went through Clary’s Grove, Mrs. Jack Armstrong had him stay while she “foxed his pants” and fed him a good dinner. She sewed strong buckskin patches on his worn breeches.

Abe liked New Salem life. He had friends all over the county, too.

“You should be a candidate for the Legislature again,” Graham told him as summer of 1834 came around. Abe had been thinking of this himself. When local Democrats suggested that they would vote for him, too, he hurried to Springfield to get John Stuart’s opinion.

“You’re sure of the election, Abe,” Stuart said.

This time Lincoln did not write a letter. He went around the county helping with the harvest, talking to friends, and making speeches. In August of 1834, Abraham Lincoln was elected representative for Sangamon County in the State of Illinois.

Only one thing marred Abe Lincoln’s pleasure in his prospects. He would be sorry to leave Ann Rutledge. She was engaged to John McNeil, she told him, and John had gone east to fetch his parents and had written a few letters to Ann. Before he left, he had bought a farm eight miles north of New Salem and persuaded James Rutledge to live on it and manage it for him. When Abe went to see Ann after his election she refused to consider breaking her engagement until John should return. But since Rutledge promised to send her away to school, Lincoln consoled himself that perhaps his absence would not matter.

The State Legislature convened on December first. As the day drew near, Lincoln, for the first time in his life, had a serious thought about his appearance. His shabbiness would be no credit to the people he represented. He thought the matter over and then tramped out to see his farmer-friend, Coleman Smoot.

“Did you vote for me, Smoot?” Abe asked directly.

“That I did,” Smoot grinned. “And I expect you to do us honor.”

“That’s what I’ve come out here about,” Lincoln admitted sheepishly. “I wondered”—he glanced down at his shabby, patched breeches, his muddy shoes, and old hat.

“I’ll loan you two hundred dollars, Abe,” Smoot offered quickly. “Your pay will be three dollars a day; you can return my loan later. Buy yourself a good suit, hat, and shoes and ride to Vandalia in the stagecoach—the state allows you travel expense.”

So when Lincoln left for the capital in November, he wore a handsome suit made by a Springfield tailor and he traveled with the other representatives. He would never wear clothes with John Stuart’s natural elegance, but neither would he disgrace the people he represented. He meant to do their business well and make himself worthy of their esteem.