3

Rejuvenate

Reenergize Your Mind and Body

Almost everything will work again if you unplug it for a few minutes, including you.

ANNE LAMOTT

University of Pennsylvania professor Alexandra Michel, a former Goldman-Sachs employee, conducted a twelve-year study of investment bankers who regularly worked between 100 and 120 hours a week. There are only 168 hours in a week. As we saw in chapter 1, entrepreneurs, executives, and other professionals already steal time from the margins with fifty-plus-hour workweeks. To work 120 hours means shortchanging everything else in life: sleep, relationships, exercise, recreation, spiritual and community activities, and more. To offset the loss, the bankers’ employer offered them round-the-clock administrative aid, meal and laundry services, and other domestic assistance.

Given their singular focus, the bankers were highly productive at the start. They came in with energy and vigor, took advantage of the extra services their employer provided, and worked hard and long, making huge strides. But it didn’t last. It couldn’t last.

“Starting in year four, bankers started to experience sometimes debilitating physical and psychological breakdowns,” Michel reported. “They suffered from chronic exhaustion, insomnia, back and body pain, autoimmune diseases, heart arrhythmias, addictions, and compulsions, such as eating disorders, causing them to exhibit diminished judgment and ethical sensitivity.” As their performance plummeted, Michel said, “They simply compensated for their diminishing output by working longer, which caught them in a cycle of escalating work hours and chronic physical and emotional distress.”1

We’re chasing our tails when we try this approach. Jack Nevison, founder of New Leaf Project Management, crunched the numbers from several different studies on long work hours. He found there’s a ceiling. Push past fifty hours of work in a week and there’s no productivity gain for the extra time. In fact, it goes backwards. One of the studies he examined found that fifty hours on the job only produced about thirty-seven hours of useful work. At fifty-five hours, it dropped to almost thirty. The more you work beyond a fifty-hour threshold, according to this study, the less productive you become. Nevison calls this the Rule of Fifty.2

That means, based on the number of hours most of us work, we’re on the edge of working backwards if we’re not doing so already. UC Berkeley management professor Morten T. Hansen compares overlong hours to squeezing an orange. “At first,” he says, “you get a lot of liquid. But as you continue to squeeze and your knuckles turn white, you extract a drop or two. Eventually, you reach the point where you’re squeezing as hard as you can, but producing no juice.”3 In one revealing study, managers found no measurable difference between the performance of workers who clocked 80 hours a week and those who simply faked it; the additional hours resulted in no real productivity gains.4 By working to the point of exhaustion, we are achieving less by doing more—the opposite of what we want. To achieve more by doing less, though, we must let go of some of our closely held misconceptions about time and energy.

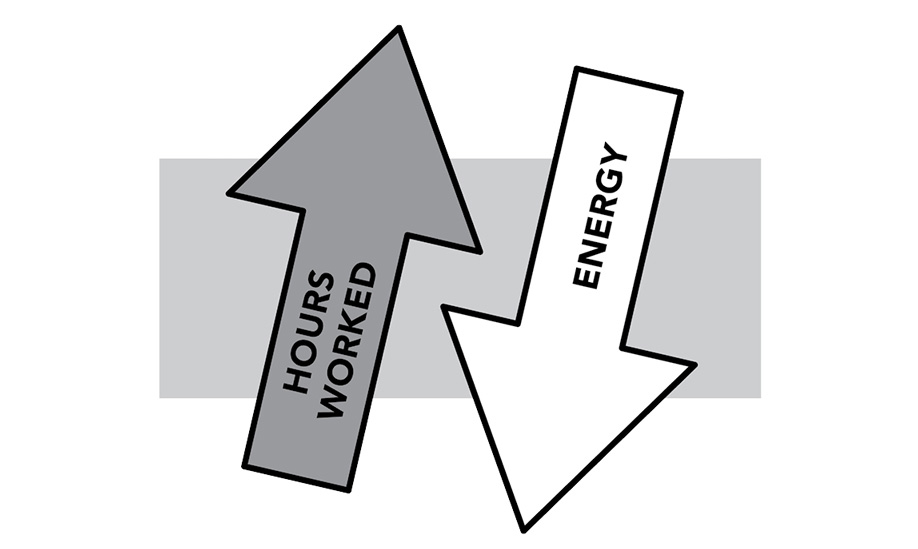

Time is fixed, but energy can flex. That means there’s an inverse relationship between hours worked and the productive expense of your energy. The more hours you work, the less productive you’ll be.

The bankers fell prey to a common productivity myth: that energy is fixed, but time can flex. They believed they could get a consistent return on their effort while expanding their hours—that they’d be just as smart, strong, and engaged at 100 hours as they were at 50. Here’s Elon Musk, founder and CEO of Tesla and SpaceX, in a classic statement of the fallacy: “If other people are putting in 40-hour workweeks and you’re putting in 100-hour workweeks, then even if you’re doing the same thing . . . you will achieve in four months what it takes them a year to achieve.”5 But the bankers and Musk have it exactly backwards. One hundred hours of work is qualitatively, not merely quantitatively, different than fifty. Time is fixed, but energy can flex. Every day contains the same number of hours, while your energy swings up and down depending on multiple variables, including rest, nutrition, and emotional health.

Most of us know this intuitively. When we’re fresh in the morning, we can accomplish twice as much as we do after lunch. That’s energy flexing. The good news is that you can make your energy flex in your favor so you get the most juice for the least squeeze. That’s what this action, Rejuvenate, is all about. Personal energy is a renewable resource, replenished by seven basic practices. We must:

- Sleep

- Eat

- Move

- Connect

- Play

- Reflect

- Unplug

Let’s start by looking at the first.

Eulogizing one of his top executives, former Disney CEO Michael Eisner said, “Sleep was one of [his] enemies. [He] thought it kept him from performing flat out 100 percent of the time. There was always one more meeting he wanted to have. Sleep, he thought, kept him from getting things done.”6 We all buy into that myth at times, but it’s nothing to celebrate. We convince ourselves we can squeeze one more meeting or task into the day if we get up earlier or go down later. It’s pervasive.

On average Americans get just under seven hours of sleep each night.7 And that number, already below the recommended eight, is probably overstated because people usually report the time they spend in bed, not the hours they actually sleep. We get about 20 percent less sleep than we think, according to researchers.8 And that’s the average! In the business world, we boast about getting even less.

Leaders at PepsiCo, Southwest, Fiat Chrysler, Twitter, and Yahoo! have all claimed to thrive on half the recommended amount of sleep.9 The bragging rights go up as the time in bed goes down, creating a self-imposed expectation among entrepreneurs and leaders at every level. If you want to be among the best and brightest, you’re supposed to be superhuman. But we’re not superhuman. Two-thirds of leaders in one survey expressed dissatisfaction with the amount of sleep they get, and more than half lamented low-quality sleep.10 It comes at a high cost.

We treat the pillow like the enemy of productivity, but skipping sleep ultimately hurts our work. The Lancet, for instance, studied surgeons who stayed awake twenty-four hours. The doctors made more mistakes, and routine tasks took them 14 percent longer. The impairment was on par with being intoxicated.11 And it doesn’t take one all-nighter for those kinds of results. In another study, people getting just six hours a night for two straight weeks functioned as if they were legally drunk.12 Rather than boosting productivity, we’re ensuring our own failure when we rob our rest.

Nightly rejuvenation is the foundation of productivity. Sufficient sleep keeps us mentally sharp and improves our ability to remember, learn, and grow. It refreshes our emotional state, reduces stress, and recharges our bodies. Meanwhile, going without sleep makes it harder to stay focused, solve problems, make good decisions, or even play nice with others.13 As neuroscientist Penelope A. Lewis explains, “Sleep-deprived people come up with fewer original ideas and also tend to stick with old strategies that may not continue to be effective.”14

That’s precisely why effective leaders and entrepreneurs stress getting adequate sleep. Consider Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos. “Eight hours of sleep makes a big difference for me,” he told Thrive Global. “That’s the needed amount to feel energized and excited.”15 Aetna chairman and CEO Mark Bertolini actually offers cash incentives for employees to prioritize their sleep. “You can’t be prepared if you’re half-asleep,” he explained in an interview. “Being [fully] present in the workplace and making better decisions has a lot to do with our business fundamentals.”16

Rejuvenating rest comes down to two things: quantity and quality. Adults—regardless of what’s on their calendars or who is demanding their time and attention—require seven to ten hours of sleep a night to perform at their peak. You need to give yourself permission to sleep as much as you find necessary to be at your best. Admittedly, that can be difficult. If your schedule is packed, you might need to sacrifice time on Facebook or Netflix (“We’re competing with sleep,” Netflix CEO Reed Hastings has admitted).17 If you have young children, you and your partner may need to sleep in shifts or even hire an overnight babysitter occasionally to ensure undisturbed rest. You might even consider going to bed at the same time your kids do for a few nights to get some extra zzz’s.

You can also increase your quantity of sleep by adding a short nap to your daily schedule. Don’t laugh; naps are my secret productivity weapon. I take one every day after lunch, and it keeps me fresh and alert all afternoon. Just don’t nap longer than twenty or thirty minutes, or you may have a hard time waking up and you’ll feel groggy, not reinvigorated. There’s a long list of leaders, artists, scientists, and others who have improved their performance by strategic napping. To name just a few: Winston Churchill, Douglas MacArthur, John F. Kennedy, J. R. R. Tolkien, and Thomas Edison.18 Don’t be surprised if it takes a while to get the hang of it. “Like skydiving, napping takes practice,” says essayist Barbara Holland.19

As for quality, there are several ways to improve that as well. Studies unanimously show that turning off all your screens (TV, phone, tablet, computer, and so on) an hour before bedtime can dramatically improve your sleep. Be intentional about your sleep environment by adding blackout shades, lowering the room temperature, and using white noise from a sound machine, phone app, or simply an electric fan in your bedroom.20 Small changes can make a huge difference, leaving you more refreshed and energized as you climb out of bed.

Practice 2: Eat

The food we eat makes an immediate, long-lasting, and powerful impact on our energy levels. There’s a reason athletes are so vigilant about their intake. The best productivity system in the world can’t help you if you are starving your body of the nutrients it needs to run at peak efficiency.

Just consider lunch. A 2012 workplace survey by Right Management found just one in five employees gets away from their desks for lunch. Another two in five eat some food at their desks. But almost 40 percent of workers and managers eat lunch “only from time to time” or “seldom, if ever.”21 We can treat lunch like an interruption, but the truth is that it pays big dividends in expanding energy. On the other hand, skipping a midday meal can leave us drowsy, foggy, and fatigued.

Leaving our desks for a meal also pays creative dividends. “Creativity and innovation happen when people change their environment, and especially when they expose themselves to nature-like environments,” says Kimberly Elsbach, an expert in workplace psychology at UC Davis Graduate School of Management. She argues that “staying inside, in the same location, is really detrimental to the creative process. It’s also detrimental to doing the rumination that’s needed for ideas to percolate and gestate and allow a person to arrive at an ‘aha!’ moment.”22 Missing lunch means you’re sacrificing breakthrough moments that could take your organization to the next level in exchange for the unbroken monotony of calls and meetings and spreadsheets and emails.

Of course, the conversation about what does or doesn’t constitute a healthy diet could go in a hundred different directions, and all of them are outside the scope of this book. However, I will share a few pieces of advice if you’ve never made a priority of healthy eating.

First, natural foods such as vegetables, fruits, nuts, and meats are better choices than practically anything you’ll find in a package. If you can’t pronounce the ingredients or it’s loaded with sugar, you might want to think twice. And be mindful when eating out; menus rarely say anything about the quality of the ingredients used.

Second, don’t assume you know what a healthy diet looks like if you haven’t studied the subject for yourself. The road to poor nutrition is paved with assumptions people make about what are and are not wise food choices. People are too often misled by products falsely advertised as “healthy,” “low fat,” or other splashy blurbs marketers throw onto packaged foods. The government’s recommended eating plan itself has changed over the years, and it is constantly scrutinized, critiqued, and criticized by many health professionals. Knowing what you should eat can be tricky, so do your research and find what works best for you.

Third, be mindful of what you drink. So-called energy drinks, soda, and many other beverages can leave you more depleted than you felt before drinking them, despite the short-term sugar rush you may feel. It’s best to stick with water as much as possible.

Fourth, research a nutritional supplement protocol for yourself. Supplements help make up for nutritional deficiencies in our diets. In terms of my personal energy level, I pay special attention to vitamin B12 and vitamin D. Both of these play a huge role in helping me manage stress and feel more energetic.

Fifth, it’s also important who you eat with. Meals are a tremendous way of building relationships. Meals aren’t just about refueling. They’re about joy and connection as well. Just like spending quality time in bed, spending quality time at the table is key for productivity.

Practice 3: Move

Too often we tell ourselves we don’t have enough energy to exercise, but exercise itself is an energizer. It gives more than it takes. In fact, few things have as direct an impact on our energy levels as a decent workout. If you get moving early, it will pay huge dividends all day long.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Only a few lifestyle choices have as large an impact on your health as physical activity.”23 A regular exercise routine has been tied to weight control, lower stress, vitality, increased energy, reduced risk of heart disease and cancer, and overall improved quality and length of life. Plus, you can achieve these benefits without spending hours a day in the gym. The CDC says, “You can put yourself at lower risk of dying early by doing at least 150 minutes a week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity.”24 That’s less than twenty-five minutes a day of some physical activity. Even a brisk walk after lunch can help you take huge strides in improving your health, losing and maintaining your weight, improving your sleep, and boosting your energy levels.

Exercise doesn’t just strengthen your body; it strengthens your mind as well. Physical activity primes our brains to operate at a higher level. Writing in the Washington Post, journalist Ben Opipari explains, “A single workout can immediately boost higher-order thinking skills, making you more productive and efficient as you slog through your workday. When you exercise your legs, you also exercise your brain; this means that a lunchtime workout can improve your cognitive performance. . . . It improves executive function, a type of higher-order thinking that allows people to formulate arguments, develop strategies, creatively solve problems and synthesize information.” And again, this doesn’t have to take a lot of time. Opipari says, “As little as twenty minutes of aerobic exercise at 60 to 70 percent of your maximum heart rate is enough.”25

I don’t usually suggest quick-and-dirty hacks when it comes to productivity, but if you’re looking to boost your mental and physical energy, create a prime atmosphere for reflection and problem solving, and improve your overall health all at the same time, try hitting the gym or going for a run or walk. It works.

High-achievers are notorious for their inability to figure out how to properly balance their home life and work life. It may sound crazy, but exercise can make a huge difference here as well. You might be thinking, “How can adding one more thing to my already-packed schedule help me balance home and work life?” That’s a great question, and it’s one research has already answered. Russell Clayton, writing in the Harvard Business Review, asserts, “New research . . . demonstrates a clear relationship between physical activity that is planned, structured, repetitive, and purposive . . . and one’s ability to manage the intersection between work and home.”26

People often say they don’t have time to exercise. But research shows that people who exercise are actually better at balancing the demands of both work and home than those who skip working out.

Clayton breaks it down to two key findings. First, he explains that “exercise reduces stress, and lower stress makes the time spent in either realm more productive and enjoyable.” Second, he notes that exercise creates a greater sense of self-efficacy, the confidence we have in our ability to get things done. Simply put, exercise lowers our stress and makes us feel strong, creating a sense that we can conquer the world. That mindset has a huge impact on how we approach both our home and work responsibilities.27 It carries over into how you approach work, engage with clients and competitors, and view your ability to crush big goals. Maintaining an exercise regimen despite often-overwhelming demands on your time forces you to sharpen your self-discipline and increase your capacity for self-sacrifice. It also helps you hone your efficiency, dedication, planning, and focus to juggle competing interests and opportunities. In short, it gives you an edge in every part of your life.

Demonstrating this point, researchers in Finland followed five thousand male twins for almost thirty years, tracking which were active and which were sedentary. They discovered regular exercise contributed to 14 to 17 percent higher long-term income levels—even between twins who have roughly the same genetic potential. The researchers concluded that exercise “make[s] people more persistent in the face of work-related difficulties, and increase[s] their desire to engage in competitive situations.”28 These traits are directly applicable in a business environment, and they add up to a massive competitive advantage in the marketplace.

Practice 4: Connect

We can’t talk about managing energy without talking about the effect other people have on our energy level. The people around us have the power to dramatically boost or drain our energy faster than almost anything else. You can get plenty of sleep, eat a healthy diet, and work out every day, but if you’re keeping yourself locked away from other people, not taking the time to invest in quality relationships with friends and family—or worse, hanging out with emotional vampires—you’re missing out on one of the most powerful energizers of all.

“The undeniable reality is that how well you do in life and business depends not only on what you do and how you do it . . . but also on who is doing it with you or to you,” says psychologist Henry Cloud in The Power of the Other. Connecting this observation to managing our energy, he says, “It’s not just about managing your workload and taking breaks; it’s just as important to manage the energy sources around you.” Productivity, in other words, is interpersonal.29

Dylan Minor, an assistant professor at Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management, demonstrated this point by studying workers at a large tech company. After identifying the high-performers, he analyzed their effect on the people around them. For the coworkers who sat within a twenty-five-foot radius of high-performers, their performance rose 15 percent, which amounted to a $1 million improvement to the bottom line.30 But as Cloud also says, “People give energy, and they take it away.”31 Minor found “negative spillover” from low-performers could have double the impact high-performers did on profits—just in the wrong direction.32

This goes beyond your organization (those you regularly deal with at work) to include your full social circle (everyone you regularly interact with). Your coworkers, colleagues, customers, and clients play a part in your energy management, and so do friends, family members, acquaintances, parishioners, and others—even Facebook friends and Twitter followers. Some of these people come with batteries included, as I heard Dan Sullivan once say. They charge you up. Others don’t, and they drain you. Either way, they all impact your energy.

For maximum rejuvenation, you must be intentional about these connections. A night out with friends, a getaway with your family, or a cup of coffee with a colleague can pay back huge dividends in energy and relationship capital over time. Similarly, a disagreeable political exchange with an old college friend on Facebook can drop you in a funk that lasts for hours. Cloud recommends a social audit. Are you surrounding yourself with energy producers or energy drains? Even if circumstances force you into relationships with negative people, knowing the effect they have can prevent the worst of it from rubbing off.

I sometimes hear people say they don’t have time for friendships. Overworked people rarely do. Connection is like sleep or exercise in that way. It’s essential for high performance, but it’s one of the first things we cut when the tasks pile high. For real productivity, however, we need to prioritize people. You are a human being, not a human doing. Maybe you’ve forgotten that, but not everything can be measured by check marks on your to-do list. Many of the best things in life happen in the spaces between our tasks, in the intentional moments set aside for other people.

Practice 5: Play

You know the old saying “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy”? It also makes Jack ineffective, uncreative, unfocused, and unproductive. Never discount the power of play in your life, no matter how many other serious things demand your time. You will always have problems to solve, deadlines to hit, and tasks to finish. That’s not going to change anytime soon. If you keep pushing fun to the back burner—maybe to some fanciful vision of a far-off retirement—you’ll miss the rejuvenating energy that play provides.

How do I define play? It’s activity for its own sake, for fun, for connection with others, or for expressing your own creativity. It’s a game like golf or a hobby like painting. It’s wrestling with the kids or throwing a ball with your dog. It’s hiking outdoors or fishing on a trout stream. It’s adventure. It’s leisure. It’s learning to play the Native American flute (one of my favorites). It’s Frisbee at the park, swimming in the sea, and tennis on the court. It’s a guitar circle. It’s charades, checkers, board games, and jigsaw puzzles. Sometimes it involves challenge and competition. Other times it’s just goofing around. Whatever the activity or venue, play is essential to rejuvenation.

Because play has no desired end product as such, it flows along on its own. And that’s its secret power. When you’re not working toward something, you’re free to be inefficient, which means you can step back and experiment, try new things, and imagine the world differently than it appears to be. As author Virginia Postrel says, “Play nurtures a supple mind, a willingness to think in new categories, and an ability to make unexpected associations. The spirit of play not only encourages problem solving but, through novel analogies, fosters originality and clarity.”33 Play produces creative breakthroughs.

We all know about the habits of highly successful people, but what about their hobbies? As psychiatrist Stuart Brown says, “Work does not work without play.”34 The best and brightest already know this. Bill Gates plays tennis. He also plays bridge with Warren Buffet. Onetime Twitter exec Dick Costolo hikes, skis, and keeps bees. And Google cofounder Sergey Brin does gymnastics, bikes, and plays roller hockey.35 These sorts of activities aren’t adjacent to their success. They are part of it. US presidents George W. Bush, Jimmy Carter, Ulysses S. Grant, and Dwight Eisenhower all painted. So did Winston Churchill. “Churchill’s great strength,” according to historian Paul Johnson, “was his power of relaxation,” and painting was a big part of that power. He took up the hobby during a bleak time in his career and kept at it the rest of his life—even through the worst of the Second World War. As Johnson concludes, “The balance he maintained between flat-out work and creative and restorative leisure is worth study by anyone holding a top position.”36

The key to that kind of restoration, as Churchill himself said, is deviating from our work routines. We use our bodies and minds differently at play than at work. “A man can wear out a particular part of his mind by continually using it and tiring it, just in the same way he can wear out the elbows of his coat,” he wrote in an essay on painting, adding an important distinction:

There is, however, this difference between the living cells of the brain and inanimate articles. . . . [T]he tired parts of the mind can be rested and strengthened, not merely by rest, but by using other parts. It is not enough merely to switch off the lights which play upon the main and ordinary field of interest; a new field of interest must be illuminated.

He went on to say, “It is no use inviting the . . . businessman who has been working or worrying about serious things for six days, to work or worry about trifling things at the weekend.”37 For rejuvenation to occur, it’s important to change things up.

That might be one reason time in nature has such restorative power. Taking a break from the busyness of life to engage with nature, even for a few minutes, can bring positive effects for our mental stamina and cognitive performance. In one study, people performing memory and attention tests upped their scores by 20 percent after walking through an arboretum.38 The time doesn’t have to be long. Short “micro-breaks” with nature have discernible benefits for our minds.39 But long, immersive stretches in nature offer big benefits for our creativity and problem-solving skills. After spending four days in the wild, disconnected from any sort of digital technology, students performed 50 percent better on a problem-solving test. “Our results demonstrate that there is a cognitive advantage to be realized if we spend time immersed in a natural setting,” said researchers.40

And the positive mental effects don’t stop at brainy stuff like focus, creativity, and problem-solving. Nature improves our mood, generosity, and a lot more.41 Spending time in nature is a great way to find physical rejuvenation. I always feel relaxed when I’m unplugged and outdoors. It turns out the reason is that nature is a stress killer, which offers a cascade of other benefits, including:

- Rejuvenated physical energy

- Reduced anxiety

- Reduced muscle tension

- Decreased stress hormones

- Lower heart rate

- Decreased blood pressure42

Many of these benefits rebound to our mental health, of course, forming a virtuous circle. We can look at these benefits like optional add-ons or upgrades to our lives. But the truth is they’re normative. We’re hardwired to spend time playing, relaxing, and resting, especially in natural environments. If you want to stay sharp, you need regular injections of recreation, exercise, and outright play into your busy schedule.

Another source of rejuvenation is reflection. This could take many forms, but most often it’s something like reading, journaling, introspection, meditation, prayer, or worship. So much of what we’ve covered so far emphasizes the body: sleeping, eating, moving, and so on. All of these things are good for the soul. But we also need to spend time intentionally rejuvenating our minds and hearts. This first section of Free to Focus is called Stop, and reflection is often the last thing we stop for—if we ever do. But we need to make time for these sorts of reflective practices. If we don’t, we run the risk of losing ourselves.

It is so easy for busy people like us to rush through life at warp speed, taking action and making decisions without ever stopping to figure out where we’re going, who we’re affecting, and what all these actions and decisions are adding up to. This lack of awareness over weeks, years, and decades creates a life lived haphazardly, on the fly, and as a reaction to outside forces. That’s not the kind of life you want to look back on.

Along with our frenetic schedules, social media and our instant-gratification culture make this doubly important. It’s possible to skip along the surface of our life and never go deeper than status updates, one-click purchases, and streaming television binges. We’ll never fully rejuvenate unless we slow down and contemplate our life and the way we move through the world.

Strive to make time for reflection every day. What ideas really matter to you? What are you feeling? Give yourself space to think through your day, including your daily decisions, wins, losses, ideas, insights, and everything else that made the day unique. This exercise ensures that you’re connected to a bigger why and that you don’t get lost in the minutiae of life. Staying firmly connected to your why will give you the energy and strength you need to complete your work and finish the race—every day.

Practice 7: Unplug

So how do you win with these practices? It’s not an empty question. Even if you buy into them, it can be hard to do them. If we’re habituated to overwork, it can be easy to stay connected to our jobs even when we’re trying to disconnect. We drift into unhelpful patterns like weekend working and skipping sleep when we should be using our margin to renew our energy. The phone is always in the pocket, the email is a click away, and notifications are pinging and buzzing, demanding your attention.

You could invest in a personal, room-size Faraday cage and shield yourself from any incoming signal. But that might be overkill. Still, we need some sort of way to ensure we unplug. Since this is a struggle for so many, I recommend creating several rules to help you disconnect during nights, weekends, and vacations. Here are four I use (with one exception you’ll find in chapter 8). Feel free to create your own and share them with anyone who will help you implement them.

First, don’t think about work. Put it out of your mind. Preoccupation with work while you’re spending time with family and friends makes you physically present but mentally absent. Even when you’re there, you’re not there. Be mindful of worry creep. When you sense yourself thinking about work, focus on something else instead.

Second, don’t do any work. This includes staying in touch and up to date. Put your phone on Do Not Disturb, ignore your email and Slack, and shut everything down. You might put your phone in a drawer. Close desktop apps like Slack or email and don’t open them during your downtime.

Third, don’t talk about work. Avoid spending downtime discussing projects, sales, promotions, or work problems. This gives you and your family a much-needed break. Give people around you permission to call foul when you drift back into jobspeak.

Fourth, don’t read about work. This includes work-related books, magazines, and blogs, as well as things like podcasts and training videos. Cultivate other interests and use your free time to develop passions that aren’t work-related.

Next to getting ample sleep, unplugging might be the most challenging of the seven practices. When researchers asked one thousand college students across ten countries to disconnect from their devices for just twenty-four hours, most couldn’t do it. “I felt like a drug addict,” said one. “I sat in my bed and stared blankly,” reported another. “I had nothing to do.”43 That’s precisely why the other practices are so important. I’m not suggesting you disconnect from all your devices; that might be helpful, but it’s a bit extreme. Instead, I am suggesting filling your rejuvenation time with other meaningful nonwork activities, such as play, connection, and reflection so you fully rejuvenate.

Renewing Yourself

I hope this chapter has blown away some longstanding myths when it comes to managing time vs. managing energy. Remember, time is not a renewable resource. It is fixed. You can’t do anything to add a single second to the day. However, energy is renewable. It flexes, and we can take positive steps to make it flex for our benefit. We can increase our energy exponentially when we sleep, eat, move, connect, play, reflect, and unplug for rejuvenation. Then we can direct that energy however we want, in ways designed to feed our why, improve our lives, and lead to the freedom we’re all looking for.

Amazing things happen when we Stop. We create space to Formulate, to get a clear picture of where we want to go and what we want our lives to become. We take the time to Evaluate, understanding exactly where we are and what our current situation looks like. And we make the time to Rejuvenate, investing in ourselves and our energy reserves through intentional steps forward in our rest, health, and relationships. It may have seemed counterintuitive to start with Stop, but I hope by now you’ve seen the value of taking a breath. As we’ve learned, you can’t get where you’re going unless you know where you are now and where you want to go. When you’ve completed the following exercises, you’re ready to move on to Step 2: Cut. That’s when you’ll really start to see your new productivity vision take shape.