7

Consolidate

Plan Your Ideal Week

A schedule defends from chaos and whim. It is a net for catching days.

ANNIE DILLARD

When fielding competing demands on our attention, we sometimes default to addressing two or more at the same time. Then we pride ourselves about our ability to multitask. The problem is, the human brain doesn’t really multitask. Instead, as journalist John Naish says, “it switches frantically between tasks like a bad amateur plate-spinner.”1

This kind of switching comes with heavy costs. When you jump between tasks, according to Georgetown computer scientist Cal Newport, “your attention doesn’t immediately follow—a residue of your attention remains stuck thinking about the original task.”2 Switching isn’t seamless. “Attention residue” gunks up our mental gears. One study by the University of California at Irvine found workers averaged twenty-five minutes to resume a task after an interruption like an email or phone call.3 By breaking our focus, switching also slows our processing ability. When we focus on one task, we filter what’s important for the completion of that task. However, when we multitask, we compromise our ability to decide what’s relevant and what’s not. We start wasting time by processing useless information, and that keeps us in a downward spiral of increasing busyness and decreasing results.

We all develop coping strategies. But if you multiply the impact of attention residue and irrelevant activity over an entire day of interruptions, the costs add up. Have you ever finished a hectic day wondering what you actually accomplished? That’s why. We stay busy, but we lose ground on the few things that matter most.

The solution is to design our work to focus on just one thing at a time. The principle is nothing new. Centuries before the advent of smartphones, email, and instant messages, Lord Chesterfield warned his son against the dangers of multitasking. “There is time enough for everything in the course of the day, if you do but one thing at once,” he said, “but there is not time enough in the year, if you will do two things at a time.”4 In this chapter we will apply Chesterfield’s lesson by learning to consolidate activities to keep your attention where it belongs: on one thing at a time. We’ll do this by discussing MegaBatching and your Ideal Week.

Most of us have heard about batching. It’s the process of lumping similar tasks together and doing them in a dedicated block of time. For instance, you might set aside time each morning and afternoon to empty all your inboxes in your email, Slack, and social media. (You may recall that those actions are part of my workday startup and shutdown rituals covered in chapter 4.) Or you might save a week’s worth of reports or proposals to review all at once. Batching is one of the best ways I know to stay focused and blast through tasks. But even dedicated batchers don’t always leverage the technique for all it’s worth.

Several years ago I started batching on a large scale—what I call MegaBatching. I started with recording my weekly podcast. I used to research and record one new episode a week. It was sometimes hard to drum up the mental energy to produce. What should have taken me an hour or two would sometimes kill an entire day. But I found my team and I could prep in advance and batch record a whole season’s worth of shows over a couple of days. Suddenly, I was free from the weekly burden and saved significant time and money.5

I found the same thing with meetings. The average professional’s weekly schedule looks like a wild, mismatched splatter of meetings. They have no overarching strategy for accepting requests, which allows other people to dictate how they spend their days. But I couldn’t afford a calendar designed by Jackson Pollock. When I realized I was the only one who cared about my focus and productivity, I started putting rules around my calendar. Today, with rare exceptions, I batch all my meetings into two days a week. I schedule all my internal team-member meetings on Mondays, and I schedule my external client and vendor meetings on Fridays. That leaves three days in the middle of the week open for intense, focused work without my having to stop what I’m doing to run off to someone else’s meeting.

MegaBatching enables me to focus for an extended period on a single project or type of activity, churning out a ton of work quickly and with much higher quality because I’m less distracted. In those dedicated blocks of time, I truly am free to focus on the thing that matters most at that moment. This is more than grouping a few things for an hour’s worth of work. We’re talking about organizing entire days around similar activities to enable you to stay focused and build momentum.

Newport argues that we need extended periods of uninterrupted time to do our best thinking. That’s what he calls deep work. This gives you the time to immerse yourself in a project and stay there for long stretches of time. What would it look like if you eliminated all those distractions and gave yourself the freedom to focus on one type of activity—uninterrupted—for three hours, five hours, maybe even a few days at a time? MegaBatching enables you to do this. It gets you in the right environment where you can do your best work without having to switch gears. When you reclaim that momentum, you can do your work better, faster, and more enjoyably than you ever imagined.

Because this sort of work is usually done best alone, Jason Fried and David Heinemeier of Basecamp call this time in the “alone zone.”6 I’ve seen this model popping up in many industries lately. For example, Intel’s management created a program to allow their employees big blocks of “think time.” During that time, according to Wall Street Journal writer Rachel Emma Silverman, “Workers aren’t expected to respond to emails or attend meetings, unless it’s urgent or if they’re working on collaborative projects.” She reported, “Already, at least one employee has developed a patent application in those hours, while others have caught up on the work they’re unable to get to during frenetic work days.”7 By allowing employees to seclude themselves to focus on important tasks—even if they aren’t urgent in the moment—Intel and other companies are reaping the benefits of increased productivity, creativity, and even new product ideas.

That said, it’s important to note that collaborative work also yields significant returns when given the appropriate level of focus. MegaBatching collaborative time allows teams to stick with challenges long enough to get the breakthroughs they need to drive results. Whether alone or together, magic happens when we focus on important tasks.

I find it’s helpful to divide time across three broad categories of activity: Front Stage, Back Stage, and Off Stage. The metaphor comes from Shakespeare’s observation in As You Like It:

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players;

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts.8

The world is a stage. It’s where we enact the story of our lives. We’re players, we have different exits and entrances, and we each play different parts—a dozen different roles any given day if we’re not careful. Let’s take each of these categories one at a time.

Front Stage. When you think of a stage, you probably imagine the front stage first. This is where the action happens and the drama unfolds—at least from the audience’s perspective. An actor’s job is acting, and he performs that role on the stage for all to see. The tasks for which you’re hired and paid constitute Front Stage activities. I’m talking key functions, primary deliverables, the line items on your performance review. For example, if you’re in sales, your Front Stage may be filled with phone prospecting, assessing client needs, or pitch meetings. If you’re a lawyer, it might be client meetings, court appearances, or contract negotiation. If you’re a corporate executive, it might include presenting marketing plans, leading high-level meetings, or casting a vision for a new product or service.

If it delivers the results for which your boss and/or customers are paying you, that’s Front Stage work. It may not be done in public, but Front Stage work enables you to fulfill your work-related calling. That only happens, though, when you have significant overlap between your Front Stage activities and your Desire Zone. The key functions of your job should intersect with where you’re the most passionate and proficient.

Your schedule may be so unbalanced right now you can’t imagine spending several hours, whole days, or even several days in a row doing Front Stage activities. If so, that’s okay; it takes time to apply what we’re learning here. But don’t let that excuse stop you from moving the right direction. Your Freedom Compass will point the way. You need to be working toward your new destination, even if the path isn’t fully clear. You’ll find some helpful strategies later in this chapter if you feel stuck.

Back Stage. We primarily see an actor on the front stage, but that’s not where he does all his work. Back stage work enables him to step out on stage and shine. The audience sees only the performance; they don’t see the initial audition, hours of rehearsals, time devoted to memorizing lines, or rituals an actor performs to produce a good show. For most of us, Back Stage includes step-two activities (specifically, elimination, automation, and delegation) plus coordination, preparation, maintenance, and development. Let’s break these down.

You know now the importance of elimination, automation, and delegation, but when will you do it? It takes time to cull lists and calendars, set up templates and processes, and assign tasks and projects. Usually these activities are important but not urgent (more on this distinction in chap. 8). As a result, it’s easy to let them go undone for weeks, months, forever. As we’ve already seen, time invested in these activities will save you countless hours in the long run. The best way to ensure you have the time to invest is to MegaBatch it with Back Stage time. By scheduling time to eliminate, automate, and delegate, you’ll get far more accomplished than if you try to squeeze these activities into the margins.

Next, Back Stage work usually includes some type of coordination. This may be as simple as meeting with your team or delegates to plan upcoming projects and tasks. Some meetings, such as an initial vision-casting meeting, may be a Front Stage activity for you, but not all of them will be. Most significant projects take weeks, months, or multiple quarters to accomplish. Once a project is up and running, for example, it will likely require regular check-ins and meetings for accountability, sharing, and collaborative work. That’s where coordination slips to the Back Stage.

It also takes Back Stage time to prepare for Front Stage work. An attorney’s preparation might include things like poring over case law or rehearsing an opening argument. For a commercial designer, it could be researching color trends or experimenting with lettering techniques for a new logo. For an executive, it might be setting the agenda for a high-leverage meeting or studying the P&L before a financial review. These activities ensure you’re ready for a great Front Stage performance.

Maintenance constitutes another key Back Stage task. Nothing can derail your productivity like broken systems, overflowing inboxes, outdated processes, and disorganized spaces. Maintenance includes everything from email management to accounting, expense tracking, file sorting, and tool and system updates—even cleaning your office. Back Stage disorganization can ruin your best Front Stage efforts. Maintenance enables you to put your best foot forward when it’s showtime.

Finally, Back Stage work includes time for personal and team development—that is, learning new skills that will enhance and streamline your performances. For an entrepreneur, this might involve attending a workshop to improve public speaking skills or developing a new registration system for webinar attendees. A professional might take a class to brush up on his skills or renew his license. This could also include time most of us spend reading publications about our fields, attending conferences, or investing time to learn new productivity methods. Development is where we make ourselves better, so we can, in turn, perform better on the Front Stage.

However you spend your time Back Stage, it’s important to recognize that Back Stage tasks are necessary for Front Stage performance. It’s also important to recognize they don’t equate to Drudgery Zone, Disinterest Zone, or Distraction Zone tasks. While you’re setting aside time to eliminate, automate, and delegate, avoid the trap of using this time to do tasks that should be eliminated, automated, or delegated. Back Stage activities will likely be less rewarding and exciting than Front Stage tasks (that’s why it helps to be intentional and schedule time for them). But they should not be miserable for you. Remember, the Back Stage makes the Front Stage possible, and all these tasks, wherever they take place, should reflect your passion and proficiency as much as possible. Consult the adjoining table for possible examples of Front Stage and Back Stage work by profession.

Off Stage. This one’s easy. Off Stage refers to time when you’re not working, when you’re away from the stage and focused on family, friends, relaxation, and rejuvenation. Off Stage is crucial to restoring your energy so you have something to offer when you come back to the stage (chap. 3). Do whatever it takes to safeguard your time Off Stage.

An actor doesn’t live on the stage; he works there. You can’t live in your job either. It’s a part of your life—a vitally important and rewarding part—but it’s not your entire life. Balance your time on stage with plenty of quality time off it. I’ll tell you more about how to plan that time in the next chapter.

Examples of Front Stage, Back Stage Work

| Occupation | Front Stage | Back Stage |

| Commercial Artist | Ad design, image editing | Billing, meetings |

| Marketing Executive | Client acquisition, planning campaigns | Managing budgets, placing ads |

| Lawyer | Client meetings, mediation | Research, filing motions |

| Salesperson | Sales calls, pitch presentations | Filing expense reports |

| Writer | Drafting content, editing content | Emails, research |

| Executive Assistant | Executing tasks, calendar management | Creating email templates or workflows |

| Coach/Consultant | Working with clients, developing content | Billing, updating your website |

| Photographer | Photo shoots, color correction | Billing, equipment maintenance |

| Owner/CEO | Providing direction, team building | Emails/Slack, meetings |

| Pastor | Teaching, counseling | Message preparation, board meetings |

| Accountant | Client meetings, filing taxes | Billing, reading about tax code changes |

| Personal Trainer | Training sessions, coaching calls | Research, advertising |

| Financial Advisor | Client meetings, preparing reports for clients | Emails, advertising your services |

| Store Manager | Team meetings, one-on-ones, hiring | Financial statements, reports |

| Public Speaker | Speaking engagements, YouTube channel | Message preparation, networking |

| Entrepreneur | Creating new products, securing clients | Establishing processes, web maintenance |

| Executive Recruiter | Prospecting, interviewing, networking | Creating templates, organizing contacts |

| IT Specialist | Troubleshooting, repairs, installs | Research, follow-up, reporting |

| Real Estate Agent | Showing houses, networking | Paperwork, filing, correspondence |

Now that we understand the three categories of activity—Front Stage, Back Stage, and Off Stage—let’s harness the power of MegaBatching with a tool called the Ideal Week. This tool allows you to plan your time the way you want to spend it. You’ve probably heard Dwight Eisenhower’s old line, “Plans are worthless, but planning is everything.”9 The workweek is far less dangerous than the battlefield, but a hundred things will militate against your productivity. A plan might not survive the first engagement with the enemy, but having planned, you’ll be better able to recover and find your footing. You’ll know what you’re shooting for.

The premise behind the Ideal Week is that you have a choice in life. You can either live on purpose, according to a plan you’ve set. Or you can live by accident, responding to the demands of others. The first approach is proactive; the second reactive. Granted, you can’t plan for everything. Things happen that you can’t anticipate. But it is a whole lot easier to accomplish what matters most when you are proactive and begin with the end in mind. That’s what the Ideal Week is designed to do. It is like a financial budget. The only difference is that you plan how you will spend your time rather than your money. And like a financial budget, you spend it on paper first.10

Here’s how the Ideal Week works: Think of a completely empty calendar for each day of the week. Most calendar apps will allow you to view a week at a glance, showing each day of the week in seven side-by-side columns. In its purest form your week is a blank slate, and you have the same amount of time as everyone else. How do you want to use it?

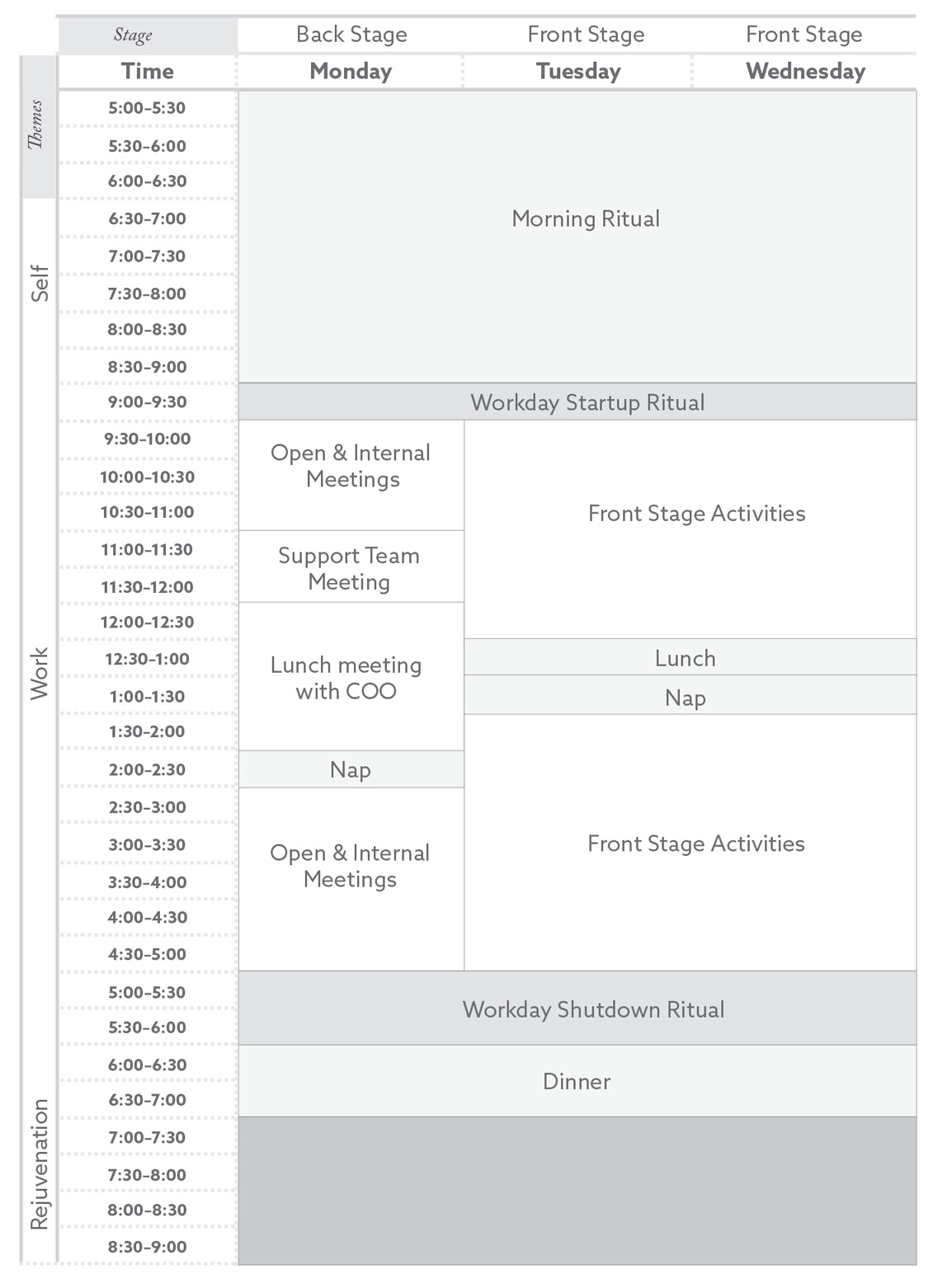

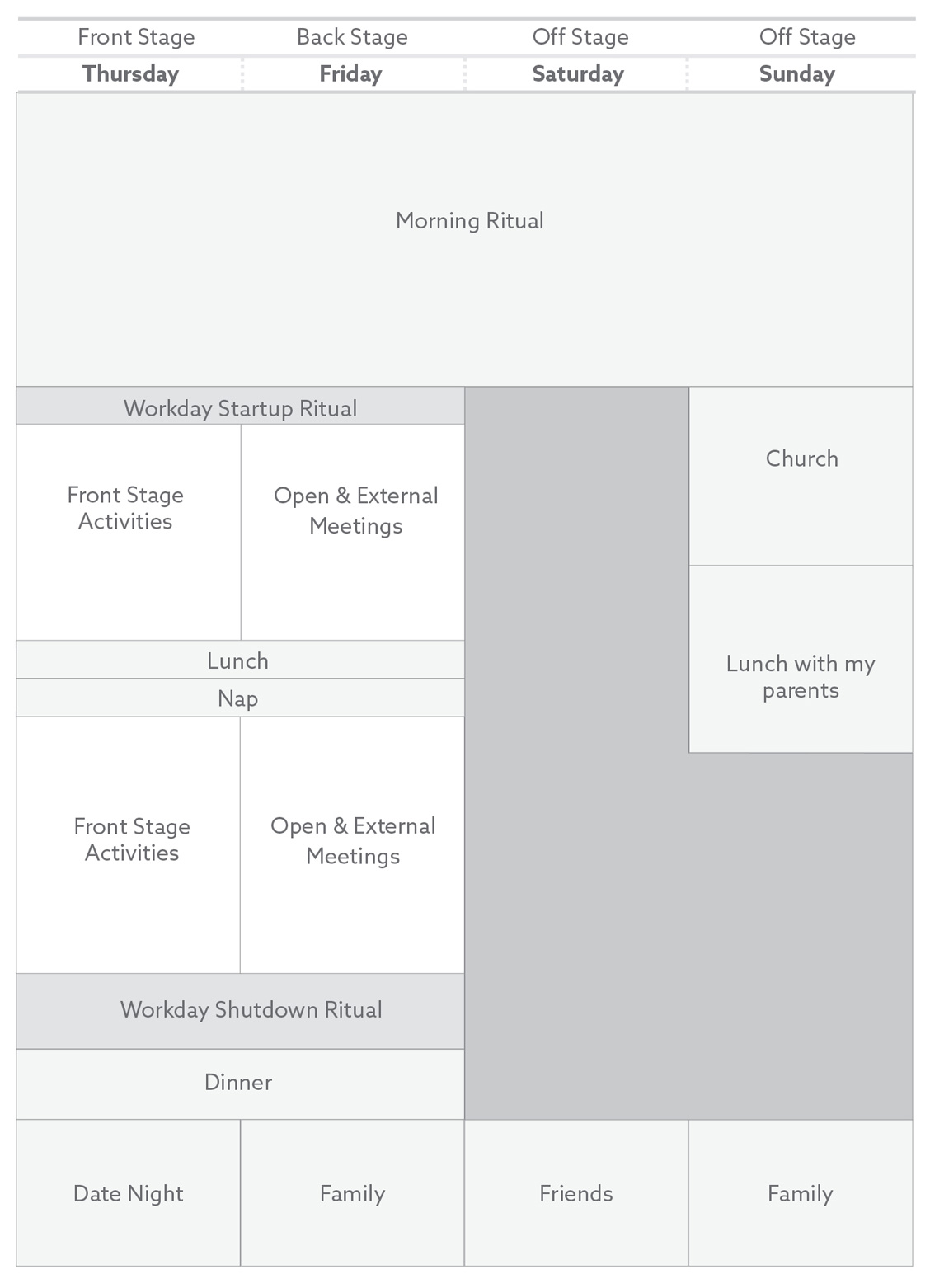

You can see how I’ve structured my Ideal Week in the adjoining example. To create your own Ideal Week, you can download a template at FreeToFocus.com/tools. I also include an Ideal Week template in my Full Focus Planner. You could even open your calendar app and create a new blank week or sketch it on a sheet of paper. Don’t worry about making it perfect, and don’t try to do this on top of your existing calendar appointments. Remember, we’re creating an ideal week, so let’s start from scratch for now. We’ll look first at stages, themes, and then individual activities. This progression allows you to take that blank canvas and give it the shape and definition you need to perform at your best.

Stages. The first step is to batch your weekly activities by stage. Decide for each day if you’ll be Front Stage, Back Stage, or Off Stage. For me, Mondays and Fridays are Back Stage time; this is typically processing email or Slack messages, organizing files, doing research, learning some new skill or capability, planning future events, or meeting with my team to coordinate projects. These could be whatever days you choose. Think of it as time you are preparing to do what you were hired to do; some days are more conducive to that than others.

The same goes for Front Stage time, which for me is Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays. I hold these days for running workshops or webinars, recording audio or video content, and hosting clients, partners, or prospects, individually or (more often) in small groups. As a company, we never hold team meetings on Thursdays; instead, we keep that day open for individual team members to use as they see fit. Many use it for their Front Stage time. Whatever days you reserve for Front Stage time, remember this is time to do what you were primarily hired to do—that is, the high-leverage work that moves your business, division, or department forward. If you’re not getting one to two Front Stage days a week, your performance will suffer.

Below is an example of my current Ideal Week so you can get a sense of how to build yours. FreeToFocus.com/tools has additional examples, plus a blank Ideal Week form to use for yourself.

When planning your Ideal Week, you also want to ensure you’re budgeting Off Stage time for rejuvenation. For me this is always Saturday and Sunday. The time might include physically resting, doing something recreational, enjoying long leisurely meals with family or friends, being in church, or building my most important relationships. It is time where I don’t work. In fact, I don’t even allow myself to think about work, talk about work, or read anything work-related (see chap. 3). Some professionals have different time demands and may need to work outside the typical workweek. That’s fine—if you schedule some sort of regular Off Stage time, preferably at least two days a week. If you’re wondering how to ensure you take this necessary time off, blocking the time on your Ideal Week is the first step.

Themes. Next, you want to indicate what type of activities you’ll do on individual days during certain blocks of time. Don’t think about individual activities or tasks right now, just broad themes. An easy way to start is to think of the morning, workday, and evening. I follow this approach and use three themes for my time: self in the morning, work in the midday, and rejuvenation in the evening. Theming the time not only helps identify what you want to do, it also helps you get in the right headspace for the various aspects of your day. Here’s how they form the day for me.

Self. I schedule the early morning hours to myself. This includes self-development, working out, prayer and meditation, and so forth. The amount of time you allow here will depend on a mix of your aspirations and your obligations. If you have kids, you might have less time to spare than an empty nester. Regardless, what matters is being intentional with the time you have.

Work. I arrive at the office by around 9:00 a.m., and I quit for the day by 6:00 p.m. Factoring an hour for lunch and a nap in the middle of the day, that is a forty-hour workweek. With the lessons we’ll cover in the next chapter, you’ll see that’s plenty to accomplish my key goals and projects. When will you start and when will you finish? Setting limits on your workday is foundational to productivity. We know from Parkinson’s Law that work expands to fill the available time; the lesson for us is that we must limit the availability or it will balloon into the early morning and late evenings. Suddenly you’re skipping breakfast and eating takeout at your desk at 7:30 p.m., and as we know from the research on overwork, there’s no payoff for those extra hours.

Rejuvenation. I reserve the last several hours of the day for rejuvenation, which includes spending time with my family, friends, and hobbies. You can’t bring your best to the rest of the day unless you schedule time to refresh.

You can use whatever labels you want and more than three if that helps. The point is to give clear shape to your day—hard starts and stops—so you know what to expect of yourself throughout. Structuring your day by theme frees you to focus on what’s in front of you; be present with who and what needs your attention; be spontaneous, knowing that there’s time reserved for work and play; or do nothing at all, which can be very rewarding. Intentional rest and relaxation is key to high performance.

Activities. Once you’ve identified stages and themes, it’s time to group the individual activities that will fall into those themes. As I mentioned earlier, Mondays and Fridays are my Back Stage days, aka meetings, meetings, meetings. By bookending my week with meetings, I’m able to reserve my midweek days for Front Stage activities.

Your Back Stage work might take more days to complete with more variance. What I find with my clients is that the exact time and variance are immaterial if you’re intentional about batching as much as possible. Whether it’s handling reports, making calls, or preparing a slide deck, batching similar tasks helps you maximize your momentum as you check off the boxes instead of shifting your focus from one thing to the next. Every time you switch and recontextualize—meeting to calls to email to meeting—it slows you down. For Back Stage days, indicate when you’ll be available for meetings, when you plan to return calls, and so on.

The exact tasks I do on my Front Stage days (Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday) change week to week depending on ongoing and one-off projects, but I always group them as best I can. The trick is to avoid doing Back Stage work during Front Stage time. And that’s harder than it sounds. The reality is that you’ll have to do some Back Stage work during every day, even if you pare it back to just checking email. The answer is to schedule it and guard against its overflow into your Front Stage time.

I schedule my workday startup and shutdown rituals every day of the workweek, whether it’s a Front Stage or Back Stage day. These rituals include a mix of Front Stage and Back Stage tasks, such as checking email and Slack messages. By bracketing these activities inside rituals and scheduling them two or three times a day, I can prevent task creep. Otherwise, I could be tempted to check Slack periodically throughout the day, opening myself up to a world of interruptions during the most valuable hours of my day. Workday startup and shutdown rituals are a great time throughout the week to process your inboxes, allowing you to get a jump on the day and then close any open loops before you break for the day. If your team requires quicker feedback, you might schedule another inbox check before leaving for lunch.

When it comes to scheduling, resist the temptation to think you can go without breaks. It’s possible, but rarely helpful. In his book Rest, Alex Soojung-Kim Pang suggests our most productive time each day will amount to four hours, maybe five. His conclusion is based on close study of the work habits of leading scientists, artists, writers, musicians, and others, along with several larger research studies. As you might have guessed by now, longer hours were indicative of low performance. The reason, as we already know, is that time is fixed but energy flexes. We can only sustain concentration for so long before diminished returns set in. The high-performers he studied whose achievements and impact were the most significant worked in focused bursts with breaks for walking, refreshment, socializing, and even play interspersed.11

To dial this in, it’s worth knowing your chronotype. In his book When, Daniel H. Pink highlights what he calls the “hidden pattern of everyday life.” We start our day upbeat and energized, but we typically drop into a low-energy trough about seven hours later. For most of us, depending on when you wake up in the morning, that’s smack-dab in the middle of the workday. Consider using the trough hours for work that requires less focus. The trough is also a perfect time for a rejuvenating break, even a nap, which can counteract the lull.12

The last thing you’ll do once you finish drafting your Ideal Week is selectively share it with team members, especially your administrative assistant, so they know when you’re available for what. It can also be helpful to share it with supportive supervisors. Since the Ideal Week affects more than the workday, you might also share it with your spouse or others close to you. Explain to them what the Ideal Week is, what you hope to gain from it, and how it will benefit them. You’re going to need their buy-in and cooperation to make this work.

A More Productive Rhythm

Lord Chesterfield, whom we quoted at the start of the chapter, viewed single-minded focus as a measure of one’s intelligence. “Steady and undissipated attention to one object is a sure mark of a superior genius,” he said.13 I don’t know if I’d go so far as to say MegaBatching and planning your Ideal Week will usher you into the ranks of genius—but it’s a great start.

Spreading your focus over a million different inputs undermines your productivity, creativity, momentum, and satisfaction. Consolidation—and the focus it provides—offers a better way. By practicing MegaBatching and intentionally structuring your week, you can create the time and space to accomplish goals that otherwise might have seemed out of reach. It’s not a matter of genius-level intellect; it’s simply a matter of focus and intentionality—two powerful forces that anyone can harness.

Keep in mind that your Ideal Week is just that—ideal. It won’t happen every week. In fact, it might not happen most weeks. Life is full of emergencies and unplanned adventures, especially for high-achievers like us. When emergencies pop up, you’ll need to pivot. The Ideal Week keeps you from getting disoriented in the process; you know exactly how to get back on track because you already planned it.

That said, once you put firm boundaries in place and force yourself to stay within them for a while, it’s amazing how natural it becomes to fall into the weekly rhythm regardless of what’s going on. You can think of your Ideal Week like a target. You won’t be able to hit the bull’s-eye every time, but you’ll hit it a lot more often once you know what you’re aiming for. Over time, you will be able to use it to guide your work so you become more focused, present, and effective.

How do you adjust for the bumps in the road that throw off your aim? The answer is found in the Weekly Preview. We’ll cover that next, along with a simple method for designing your days.