Babesia is another name for piroplasm, one of the protozoan parasites belonging to the order Haemosporidia. These are generally relatively large parasites within the red blood cells and are pear-shaped, round or oval. Multiplication is by division into two or by budding. Infected cells frequently have two pyriform parasites joined at their pointed ends. Sexual multiplication takes place in the tick.

Nearly all the domestic mammals suffer from infection with some species of Babesia; sometimes more than one species may be present. The general signs are the appearance of fever in eight to 10 days after infection, accompanied by haemoglobinuria, icterus; unless treated, 25 to 100 per cent of the cases are fatal. Red blood cells may be reduced in number by two-thirds. Convalescence is slow and animals may remain ‘salted’ for three to eight years.

Transmission Development occurs in certain ticks which transmit the agent to their offspring. The various species are similar, but are specific to their various hosts. The ticks should probably be regarded as the true or definite hosts, while the mammal is the intermediate host.

Cats Babesia felis is a (rare) cause of lethargy, inappetence and anaemia, and occasionally jaundice and death.

Cattle (See RED-WATER FEVER.) Red-water in the UK and Ireland as well as the tropics is a most important disease.

Dogs They are affected by B. canis. It is also a ZOONOSIS. It results in anaemia and also reproductive and infertility problems with ENDOMETRITIS and ABORTION in bitches and EPIDIDYMITIS and ORCHITIS in dogs. It is not in the UK and animals going to New Zealand and Australia have to be blood tested.

Sheep Ovine babesiosis may be due to at least 3 species of Babesia. There is a relatively large form, Babesia motasi, which is comparable to B. bigemina of cattle, and which produces a disease, often severe, with high temperatures, much blood-cell destruction, icterus and haemoglobinuria. This is the ‘carceag’ of Eastern and Southern Europe. The second parasite, of intermediate size and corresponding to B. bovis of cattle, is Babesia ovis. It produces a much milder disease with fever, jaundice and anaemia, but recoveries generally occur. The small species is Theileria ovis, which appears to be similar to T. mutans of cattle and is relatively harmless to its host.

B. motasi, B. ovis, and T. ovis are all transmitted by Rhipicephalus bursa.

Animals recovered from T. ovis infection apparently develop a permanent immunity to it. The disease occurs in Europe, Africa, Asia, and North America.

Signs In acute cases the temperature may rise to 41.5° C (107° F), rumination ceases, there is paralysis of the hindquarters, the urine is brown, and death occurs in about a week. In benign cases there may only be a slight fever for a few days with anaemia.

A theileriosis, caused by T. hirci, has been described from sheep in Africa and Europe. It causes emaciation and small haemorrhages in the conjunctiva.

A disease of cattle caused by Clostridium haemolyticum (Cl. oedematiens) type D.

(See PULLORUM DISEASE OF CHICKS.)

This genus of Gram-positive rod-shaped organism contains many species, some of which are not regarded as pathogenic, and some that are. They are found in soil, water, and on plants. Spores formed by bacilli are resistant to heat and disinfectants, and this fact is important in connection with B. anthracis, the cause of ANTHRAX. Another pathogenic bacillus is B. cereus, a cause of food poisoning and also of bovine mastitis. (See BACTERIA.)

An antibacterial formerly used as a feed additive; its use for this purpose has been banned in the EU.

Back-cross is the progeny resulting from mating a heterozygote offspring with either of its parental homozygotes. Characters in the back-crosses generally show a 1:1 ratio. Thus, if a pure black bull is mated with pure red cows (all homozygous), black calves (heterozygotes) are produced. If the heifer calves are ‘back-crossed’ to their black father, their progeny will give one pure black to every one impure black. If a black heterozygous son of the original mating is mated to his red mother, the progeny will be one red to one black.

Back-crossing can be employed as a means of test-mating, or test-crossing to determine whether a stock of animals is homozygous, when it will never throw individuals of different type, or whether it is heterozygous, when it will give the two allelomorphic types. (See GENETICS, HEREDITY AND BREEDING.)

(See STRIP-GRAZING.)

A disease of pigs first described in Belgium in 1960, and recognised 8 years later in Western Germany (where it is colloquially known as ‘banana disease’). It has been recorded in the UK, with 20 cases occurring in a single herd.

Signs A sudden and sporadic condition affecting pigs weighing over 50 kg. In the acute stage, the animal shows signs of pain, has difficulty in moving, becomes feverish, loses appetite and appears lethargic, and shows a characteristic swelling on one or both sides of the back. When only one side is affected, spinal curvature occurs with the convexity of the curve towards the swollen side.

The colloquial name ‘banana disease’ apparently arose from arching (as compared with lateral curvature) of the back, which is often seen in affected animals.

Some pigs die from acidosis and heart failure; some recover, apparently completely; while others are left with atrophy of the affected muscles resulting in a depression in the skin parallel to the spine. Some examples of BMN are discovered only in the slaughterhouse.

Post-Mortem examination reveals necrosis and bleeding, especially in the longissimus dorsi muscle, as well as the widely recognised condition known as PSE or pale soft exudative muscle.

Causes The disease is thought to be associated with stress; it is probable that heredity also comes into the picture.

These are a very common companion animal that is found in urban and country areas including schools and also they produce eggs. They are also used for showing. In a 2010 Greater London survey showed most had good living conditions and were able to express their natural behaviours, although three quarters of owners did not comply with the DEFRA regulations for catering waste. (See also ANIMAL BY-PRODUCTS REGULATIONS 2003; POULTRY AND POULTRY KEEPING.)

The temporary presence of non-muliplying bacteria in the blood.

Microscopic single-cell plants with important functions in nutrition and in disease processes. According to peculiarities in shape and in group formation, certain names are applied: thus a single spherical bacterium is known as ‘coccus’; organisms in pairs and of the same shape (i.e. spherical) are called ‘diplococci’; when in the form of a chain they are known as ‘streptococci’; when they are bunched together like a bunch of grapes the name ‘staphylococcus’ is applied. Bacteria in the form of long slender rods are known as ‘bacilli’; wavy or curved forms have other names. (See illustration on next page.)

Spore-Formation Some bacteria have the power to protect themselves from unfavourable conditions by changing their form to that of a ‘spore’. These are very resistant to adverse environmental conditions. It is most commonly seen in species of Bacillus and Clostridium.

Size Bacteria vary in size from less than one MICRON (one-thousandth of a millimetre) diameter, in the case of streptococci and staphylococci, up to a length of 8 microns, in the case of the anthrax bacillus.

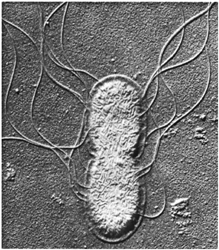

Mobility Not all bacteria possess the power of movement, but if a drop of fluid containing certain forms of organism which are called ‘motile’ is examined microscopically, it will be observed that they move actively in a definite direction. This is accomplished, in the motile organisms, by means of delicate whip-like processes called FLAGELLAE which thrash backwards and forwards in the fluid and propel the body onwards.

1. Microscopical In order to satisfactorily examine bacteria microscopically, a drop of the fluid containing the organisms is spread out in a thin film on a glass slide. The organisms are killed by heating the slide, and the details of their characteristics made obvious by suitable staining with appropriate dyes. (See under GRAM-NEGATIVE; also ACID-FAST ORGANISMS.)

Bacteria. Photomicrographs of 1. Bacillus anthracis (× 4200); 2. Clostridium tetani (× 3250) (showing the characteristic drum-stick appearance); 3. Streptococcus pyogenes (× 3000).

Some bacteria of veterinary importance |

|

Name |

Associated or specific diseased conditions caused |

|

|

Actinobacillus lignieresii |

Actinobacillosis, wooden tongue. |

Aequuli |

Fatal septicaemia in foals and pigs. |

A. pleuropneumoniae |

Pleuropneumonia in pigs. |

Arcanbacterium pyogenes |

Abscesses in liver, kidneys, lungs or skin in sheep, cattle and pigs especially; present as a secondary organism in many suppurative conditions; causes summer mastitis in cattle. Was called Corynebacterium pyogenes and then Actinomyces pyogenes. |

Actinomyces bovis |

Actinomycosis, lumpy jaw. |

Aeromonas shigelloides |

Chronic diarrhoea in cats. |

Bacillus anthracis |

Anthrax in all susceptible animals. |

Bacillus cereus |

Bovine mastitis; food poisoning. |

Bacillus licheniformis |

Abortion in cattle, ewes. |

Baccilus piliformis |

Tyzzer’s disease. |

Bacteroides species |

Foot infections in horses. |

Bartonella henselae |

Cat-scratch fever in man and angiomatosis. |

Bartonella vinsonii |

Dogs. |

Bibersteinia trehalosi |

Sudden death, septicaemia in sheep. Formerly Pasteurella trehalosi. |

Brachyspira hyodysenteria |

Swine dysentery. Formerly Serpulina hyodysenteriae and before then Treponema hyodysenteriae. |

B. pilosicoli |

Colitis in pigs. |

Bordetella bronchiseptica |

Complicates distemper in the dog. Kennel cough. Atrophic rhinitis. |

Brucella abortus |

Brucellosis abortion, undulant fever in man (in part). |

Brucella melitensis |

Brucellosis in goats; Malta fever and undulant fever in man (in part). |

Campylobacter fetus |

Infertility, abortion. |

C. jejuni |

Abortion. |

Chlamydophila abortus |

Enzootic abortion in sheep. |

Chlamydophila psittaci |

Psittacosis in parrots, ornithosis in other birds and mammals including man. |

Clostridium botulinum (five types – A to E) |

Botulism in man and animals. |

Cl. chauvoei |

‘Black-quarter’ (and also pericarditis and meningitis in cattle) in cattle and partly in sheep. |

Cl. difficile |

Chronic diarrhoea in dogs and piglets. |

Cl. haemolyticum novyi |

‘Bacillary haemoglobinuria disease’ in cattle, sheep; septicaemia in horses and pigs (wound infection). (Formerly Clostridium novyi Type D.) |

Cl. septicum |

Gas gangrene in man; black-quarter; braxy in sheep. |

Cl. novyi |

Type B Black disease in cattle, sheep. |

Cl. perfringens A |

Enterotoxaemia in sheep, goats. (Formerly Cl. welchii A.) |

Cl. perfringens B |

Lamb dysentery, haemorrhagic enteritis in sheep, goats. (Formerly Cl. welchii B.) |

Cl. perfringens C Subtype 1 |

Struck in sheep. (Formerly Cl. welchii A=C.) |

Subtype 2 |

Necrotic enteritis in USA. |

Cl. perfringens D |

Pulpy kidney, enterotoxaemia in sheep, goats. (Formerly Cl. welchii D.) |

Cl. sordellii |

Abomasitis and enterotoxaemia in cattle, sheep. |

Cl. tetani |

Tetanus in man and animals. |

Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis |

Caseous lymphadenitis in sheep; goats and occasionally cattle, some cases of ulcerative lymphangitis and acne in horses. |

C. equi |

A cause of pneumonia in the horse and of tuberculosis-like lesions in the pig. |

Dermatophilus congolensis |

Chronic dermatitis. Lumpy wool, strawberry foot-rot in sheep. |

Group EF-4 bacteria |

Pneumonia in dogs and cats, and isolated from human dog-bite wound. |

Dichelobacter nodosus |

Foot-rot in sheep. Necrosis of skin or mucous membrane in rabbits after their resistance has been lowered by some other pathogen. Formerly Fusiformis nodosus then Bacteroides nodosus. |

Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae |

Swine erysipelas. |

Eschicheria coli (subtypes are many) |

Always present in alimentary canal as commonest organism; becomes pathogenic at times, partly causing enteritis, dysentery (lambs), scour (calves and pigs), cystitis, abortion, mastitis, joint-ill, etc. |

Fusobacterium necrophorum |

Associated with foot-rot in sheep, foul-in-the-foot in cattle; calf diphtheria; quittor, poll evil, and fistulous withers in horses; necrosis of the skin in dogs, pigs and rabbits; navel-ill in calves and lambs; various other conditions in bowel and skin. (Formerly Fusiformis necrophorus.) |

Histophilus somni |

‘Sleeper syndrome’, pneumonia, septicaemia in cattle. (Formerly Haemophilus somnus.) |

H. parainfluenzae |

Chronic respiratory disease in pigs. |

H. parasuis |

Chronic respiratory disease in pigs. |

Klebsiella pneumonia |

Metritis in mares; pneumonia in dogs, mastitis in pigs, cattle etc. |

Lawsonia intracellularis |

Proliferative enteropathy, proliferative haemorrhagic enteropathy, necrotic enteropathy, regional ileitis in pigs. |

Leptospira icterohaemorrhagiae |

Leptospiral jaundice, or enzootic jaundice of dogs; Weil’s disease in man. |

Lept. canicola |

Canicola fever in man and nephritis in dogs. |

Lept. hardjo-bovis and Lept. hardjo-prajitno |

Abortion, infertility in cattle, bovine mastitis and milk drop syndrome. |

Listeria monocytogenes |

Listeriosis. |

Mannheimia haemolytica |

Pneumonia and pasteurellosis in ruminants. (Formerly Pasteurella haemolytica.) |

Moraxella bovis |

New Forest eye in cattle, keratoconjunctivitis. |

Mycobacterium bovis |

Bovine tuberculosis. |

Myc. avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP) |

Johne’s disease of cattle and other ruminants. (Formerly Myc. Johnei.) |

Myc. Tuberculosis |

Tuberculosis in man and animals. |

Pasteurella multocida |

Fowl cholera. Haemorrhagic septicaemia in cattle. |

P. tularensis |

Tularaemia in rodents. |

Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

Mastitis in cattle, contaminant on bacteriological culture. |

P. mallei |

Glanders in equines and man. |

P. pseudomallei |

Melioidosis in rats and man; occasionally in dogs and cats. |

P. pyocyanea |

Suppuration in wounds, otitis in the dog. |

Salmonella abortus equi |

Contagious abortion of mares naturally, but capable of causing abortion in pregnant ewes, cows, and sows experimentally. |

S. abortus ovis |

Contagious abortion of ewes occurring naturally. |

S. dublin |

Causes enteritis, sometimes abortion. |

S. gallinarum |

Klein’s disease or fowl typhoid. |

S. pullorum |

Pullorum disease. |

S. cholerae suis |

Salmonellosis septicaemia in pigs. |

S. typhimurium |

Salmonellosis. |

Staphylococcus albus |

Suppurative conditions in animals. |

Staph. aureus |

Suppurative conditions in animals and man, especially wound infections where other pus-producing organisms are also present. Present in various types of abscess, and in pyaemic and septicaemic conditions. Cause of mastitis in cows. |

Staph. hyicus |

A primary or secondary skin pathogen causing lesions in horses, cattle, and pigs. It may also cause bone and joint lesions. |

Staph. pyogenes |

Often associated with the other staphylococci in above conditions; causes mastitis in cows. |

Streptococcus agalactiae |

Mastitis in cattle. |

Strep. dysgalactiae |

Mastitis in cattle, arthritis in sheep. |

Strep. equi |

Strangles in horses; partly responsible for joint ill in foals and sterility in mares. |

Str. pyogenes |

Many suppurative conditions, wound infections, abscesses, etc.; joint-ill in foals. (In the above conditions various other streptococci are also frequently present.) |

Str. suis |

Infects not only pigs but also horses and cats. |

Str. uberis |

Mastitis in cattle. |

Str. zooepidemicus |

Wounds in horses; mastitis in cattle and goats. |

Taylorella equigenitalis |

Contagious equine metritis. (Formerly Haemophilus equigenitalium.) |

Vibrio |

(see under CAMPYLOBACTER) |

Yersinia enterocolitica |

(see under YERSINIOSIS) |

Y. pestis |

Plague in man and rats. In an often subclinical form this may also occur in cats and dogs. |

Y. pseudotuberculosis |

(see under YERSINIOSIS) |

For other, non-bacterial infective agents, see VIRUSES; RICKETTSIA; MYCOPLASMA; CHLAMYDOPHILA. |

|

2. Cultural characteristics By copying the conditions under which a particular bacterium grows naturally, it can be induced to grow artificially, and for this purpose various nutrient substances known as media are used. (See CULTURE MEDIUM.)

After a period of incubation on the medium on previously sterilised Petri dishes or in tubes or flasks, the bacteria form masses or colonies, visible to the naked eye.

The appearance of the colony may be sufficient in some instances for identification of the organism.

3. (See LABORATORY TESTS.)

4. Animal inoculation This may be necessary for positive identification of the organism present in the culture. One or more laboratory animals are inoculated and, after time allowed for lesions to develop or signs to appear, the animal is killed and a post-mortem examination made. The organisms recovered from the lesions may be re-examined or re-cultured. This procedure is now rarely used in the United Kingdom and requires Home Office licensing.

Some pathogenic bacteria adhere to the mucous membrane lining the intestine, and this characteristic may be an important criterion of virulence. Bacteria which possess this property include E. coli, Salmonella typhimurium, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Moraxella bovis.

Many strains of E. coli have a filamentous protein antigen called K88. This enables K88-positive E. coli to adhere to piglets’ intestinal mucosa and to multiply there. K99 is the main adhesive antigen in cattle.

A disease of fish caused by poor water quality and infected with filamentous bacteria including Flavobacterium spp. The bacteria-infected gills become swollen and coated with mucus; asphyxia follows. Treatment may include restoration of good quality aquatic environment, and the use of potassium permanganate, benzyl permanganate, benzylkonium chloride, diquat or chloramine T copper sulphate, and zinc-free malachite green may be used if fungal infection is also present. Dosage must be carefully calculated to avoid toxic side effects.

Bacterial kidney disease may affect farmed fish. Signs include pinpoint haemorrhages at the base of pectoral fins and on their sides; occasionally ‘popeye’ may be seen. In pacific salmon, cavernous spaces may be found in the muscles. Prolonged treatment with sulfonamides in the feed may control the disease, which may be due to infection by a coccobacillus carried by wild fish.

Bacterium about to divide. Salmonella dublin in the process of division into 2. Note also the flagellae.

An agent that destroys bacteria such as some disinfectants and antimicrobial agents. These compounds are thus described as bactericidal. Compare with BACTERIOSTATIC.

Bacteriophages are viruses which multiply in and destroy bacteria. Some bacteriophages have a ‘tail’ resembling a hypodermic syringe with which they attach themselves to bacteria and through which they ‘inject’ nucleic acid. ‘Phages’ have been photographed with the aid of the electron micro-scope. The growth of bacteriophages in bacteria results in the lysis of the latter, and the release of further bacteriophages. Phage-typing is a technique used for the identification of certain bacteria. Individual bacteriophages are mostly lethal only to a single bacterial species.

An agent which inhibits the growth of micro-organisms, as opposed to killing them. The term is often used to describe antimicrobial activity. Compare with BACTERICIDE.

Species of this anaerobic bacterium, including B. melaninogenicus, are frequently isolated from equine foot lesions and wounds. B. nodosus (now called Dichelobacter) is one of the organisms found in foot-rot in sheep.

Presence of bacteria in the urine. Bovine tuberculosis-infected badgers often excrete the organism in their urine.

A method of determining bacterial numbers and is routinely used to test milk in the UK and other countries for human consumption. It indicates contaminants, the hygiene level of milk production and mastitis. The Bactoscan machine automatically separates out bacteria by centrifugation, they are then stained and counted. (See MILK TESTING.)

A group of viruses affecting insects. They are very host-specific and have been used in the control of specific insect pests while leaving beneficial species unharmed. Interest has also been shown in the possibility of using them as carriers of antigens in genetically engineered vaccines.

Several species of badger inhabit different parts of the world. The so-called true badger, Meles meles, can grow up to 80 cm long, excluding tail. It is an omniverous animal with greyish coat and black-and-white stripes on the face. Badgers live in extensive underground burrows called setts.

Tuberculosis in badgers caused by Mycobacterium bovis was first described in Switzerland in 1957, and in England in 1971. Transmission of the infection to cattle led to their reinfection in the south-west of England initially but then spread to the Midlands and Wales. Badgers are now regarded as a significant reservoir of M. bovis infection. However, a policy of culling badgers in TB-affected areas has been controversial. Legal culling ceased in 1996 but has since been reintroduced to a limited extent.

The 2003 Krebs report on bovine tuberculosis in cattle and badgers recommended that badger culling should end in most of the UK. It would be replaced by a trial in areas repeatedly affected by TB. The so-called ‘Krebs trial’ compared the effectiveness of culling all badgers in limited areas with the results of culling only those badgers assumed to be linked with bovine TB in other areas, and with no culling in a third area. In areas where all badgers were culled this resulted in other badgers recolonising the areas (perturbation).

An injectable vaccine has been licensed for badgers, and work progresses on oral vaccination. There is some work on developing a vaccine to protect cattle against TB.

This makes it an offence to damage, destroy or obstruct a sett, disturb a badger in a sett, or put a dog into a sett.

This legalises euthanasia of a dog, and disqualification of its owner from keeping a dog, after the offending dog has killed, injured or taken a badger, or the dog’s owner has ill-treated or dug a badger out of its sett.

An ancient native breed recorded since the 1380s; the name is derived from the Bagot family of Blithfield Hall, Staffordshire, England. They are medium-sized with horns and long hair which is (ideally) black from the nose to behind the shoulder and then white.

Bakery waste has been fed to pigs. It is much safer to use than swill and it is legal to feed provided that it contains no animal protein. Biotin deficiency may result if it is fed to excess.

The balance between what is taken in from the diet and what is excreted. For example, if an animal excretes more nitrogen than it receives from the protein in its feed, it is in negative nitrogen balance and losing protein. Similarly, reference is made to water balance, sodium balance and electrolyte balance.

(See PENIS AND PREPUCE, ABNORMALITIES AND LESIONS.)

Inflammation of the prepuce and penis. It occurs as infectious penoposthitis in cattle infected with bovine herpes 1 virus. Enzootic penoposthitis occurs in sheep and is often known as ‘PIZZLE ROT’.

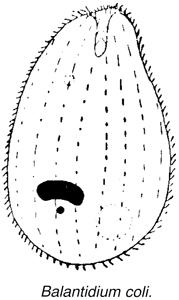

A ciliated, protozoon parasite of pigs’ intestines. As a rule, it causes no harm; but if the pig becomes debilitated from other causes, it can act as a secondary invader causing dysentery. The parasite is pear-shaped and about 80 microns long by 60 microns broad. The nucleus is sausage-shaped.

An inherited lethal disease, causing alopecia, skin cracking and ulceration with progressive loss of weight or failure to grow. It is found in the descendants of a Canadian Holstein in Australia. Inherited epidermal dysplasia has been suggested as a more appropriate name. A single autosomal recessive gene is thought to be involved.

Discarded pieces of this may be swallowed by cattle and give rise to traumatic pericarditis. In Britain, it has largely been replaced by plastic baler twine. (See under HEART DISEASES.)

A technique of clinical examination in which the movement of any body or organ, suspended in a fluid, is detected.

An acronym for BRONCHIAL ASSOCIATED LYMPHOID TISSUE, the lymph tissue present in the lungs.

(See BACK MUSCLE NECROSIS.)

Used as a livestock feed ingredient in the tropics when home production exceeds export requirements. Birds have a limited capacity to digest it and a 7.5 per cent upper limit of broiler diets is set.

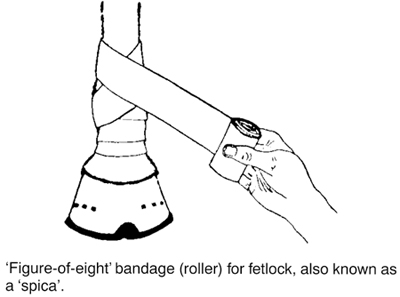

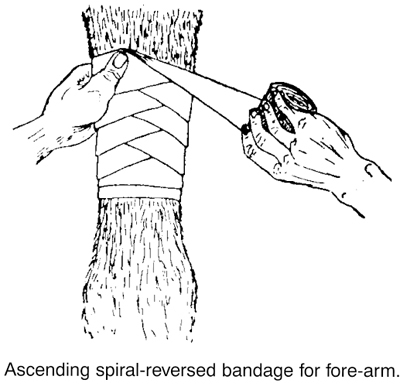

The application of bandages to veterinary patients is much more difficult than in human practice, because not only must the bandage remain in position during the movement of the patient, but it must also be comfortable, or it will be removed by the teeth or feet; and it must be so adjusted that it will not become contaminated by either urine or faeces.

Wounds often heal more readily if left uncovered, but bandaging may be necessary to give protection against flies and the infective agents which these carry. Much will depend upon the site of the wound, its nature, and the environment of the animal.

Bandages may be needed for support, and to reduce tension on the skin. The Robert-Jones bandage (a padded, stiffened, supporting bandage) and splints are commonly used in orthopaedics. (See also illustration.)

A small variety of chicken also called MINIATURE CHICKENS; most larger chicken breeds now have a bantam type, or small counterpart. The name derives from Bantam, which was once a major seaport in Indonesia and where sailors restocked with provisions after long sea voyages. They found the small live birds useful as fresh food on their voyages. When bantams are of a particular breed they will have the breed’s characteristics, but usually weigh a quarter to a fifth of the standard breed. They make good pets and should be tended and fed in the same way as other chickens. They can be good egg layers and are good mothers. They are often used for hatching eggs of other chickens. Old English bantam roosters were used for fighting in Europe. The life expectancy is about one to three years. The true bantams (no larger breed counterpart) include SEBRIGHT, DUTCH and PEKIN breeds.

The term is used for other small types of poultry besides chickens.

A condition of rabbits, mice, rats and gerbils kept in groups, where a dominant individual chews the hair or fur of a subservient individual. The appearance of the barbered pelage is as if were shaved with a clipper – a stubble is formed. Treatment is to remove the dominant animal or the affected one.

Barbiturates are derivatives of barbituric acid (malonyl-urea). They include a wide range of very valuable sedative, hypnotic or anaesthetic agents. Several are used in veterinary practice, including pentobarbitone, phenobarbitone and thiopentone. An overdose is often used to euthanase dogs and cats; and farm animals where the brain is required for examination, as in suspected BSE cases.

In case of inadvertent barbiturate poisoning, use a stomach tube and keep the animal warm. Treatment includes CNS stimulants, e.g. bemegride, doxapram, caffeine or strong coffee.

(See also under EUTHANASIA; HORSE-MEAT.)

While not an essential mineral in vertebrates, there is some evidence that barium it is required by certain molluscs, including those that are farmed (oysters, mussels, etc.). Barium salts are given as meals or enemas to render the alimentary tract opaque to X-rays.

(See under X-RAYS.)

Barium chloride has been used in rat poison; the bait may be eaten by domestic pets.

The signs are excessive salivation, sweating (except in the dog), muscular convulsions, violent straining, palpitation of the heart and, finally, general paralysis.

Treatment Induce vomiting or use a stomach pump to remove the poison. Epsom salts dissolved in water act as an antidote by converting the chloride into the insoluble sulphate of barium.

Barium sulphate, being opaque to X-rays, is given by the mouth prior to a radiographic examination of the gastrointestinal tract for diagnostic purposes. (See X-RAYS.)

Barium sulphide has sometimes been used as a depilatory for the site of surgical operations.

A change in the tone of a dog’s bark occurs in many cases of rabies.

Bark eating by cattle should be regarded as a sign of a mineral deficiency, e.g. manganese and phosphorus. The remedy is use of an appropriate mineral supplement.

A maladjustment syndrome in which a violent breathing action results often in a noise like a dog barking.

A major type of cereal grain used in almost all types of farm livestock and also in many pet feeds. It has a relatively high energy level (not as high as RYE or WHEAT) and low protein content (but higher than other cereals except wheat used for livestock).

As with wheat (and to a much lesser extent, oats) an excess of barley can kill cattle and sheep not gradually accustomed to it. The main signs are severe acidosis and death. Treatment is sodium bicarbonate, by injection; gastric lavage; or rumenotomy.

It is important that barley should not be fed in a fine, powdery form. To do so is to invite severe digestive upsets, which may lead to death. Especially if ventilation is poor, dusty food also contributes to coughing and may increase the risk of pneumonia.

The American name for sarcoptic mange in cattle.

A medium-heavy breed of chickens originating from Holland. The colours include double laced with a single vertical comb and yellow legs. Other colours include white, black, brown, partridge, blue and blue laced varieties. They produce dark brown eggs. The males weigh about 3.5 kg (7.5 lb) and the hens 2.5 kg (5.5 lb).

Nerve endings that detect changes in pressure.

A breed used for meat and eggs and often called ‘Rockies’. They are used in AUTOSEXING to produce different colours for the sexes, such as the Welbar, by crossing the WELSUMMER and the Legbar with the LEGHORN. Hens are crossed with RHODE ISLAND RED males to produce BLACK ROCK CHICKENS.

A protective dressing for the hands and arms of veterinarians engaged in obstetrical work or rectal examinations.

A castrated male pig.

At each of the heels of the horse’s foot the wall turns inwards and forwards instead of ending abruptly. These ‘reflected’ portions are called the bars of the foot. They serve to strengthen the heels; they provide a gradual rather than an abrupt finish to the important wall; and they take a share in the formation of the bearing surface, on which rests the shoe.

Diagram of the position of the bars of the horse’s foot. The dotted line shows the outline of the wall and frog.

The bars are sometimes cut away by farriers or others, who hold the erroneous idea that by so doing they allow the heels of the foot to expand; what actually happens in such instances is that the union between the component parts of the foot is destroyed, and the resistance to contraction which they afford is lost. They should therefore be allowed to grow and maintain their natural prominence. (See also illustration.)

They are associated with animal disease. Bartonella henselae can result in ‘cat scratch disease/fever’ and bacillary angiomatosis in humans. The organism has been found in cats but not dogs. Bartonella vinsonii is found in dogs.

Treatment Neoarsphenamine has been used. It is important to perform effective ectoparasite control.

Infection with Bartonella organisms, which occasionally occurs in dogs and cattle but is of importance in laboratory rats. Signs are mainly those of anaemia.

A small brown and white dog, originating in Africa, which is unable to bark. Inheritable congenital defects include haemolytic anaemia, inguinal hernia and persistent pupillary membrane (See PUPILLARY MEMBRANE, PERSISTENT). They may also inherit the condition intestinal lym-phangiectasia, which causes loss of protein from the gut. They also show PYRUVATE KINASE DEFICIENCY and FANCONI SYNDROME. Basenji bitches normally have only one reproductive cycle a year.

Basic slag is a by-product of the smelting industry often used as a fertiliser. It has caused poisoning in lambs, which should not be allowed access to treated fields until the slag has been well washed into the soil. Adult sheep have also been poisoned in this way, scouring badly, and so have cattle. In these animals the signs include: dullness, reluctance to move, inappetence, grinding of the teeth, and profuse watery black faeces.

A normal commensal fungus of the alimentary tract of frogs and toads which can cause disease in frogs. It can enter through wounds and is seen as hyperaemia and sloughing of the skin on the underside and may cause abnormal behaviour. For example, water-dwelling species may opt to go on land and vice versa. It is usually fatal and may be zoonotic.

A type of white blood cell. (See under BLOOD.)

Blue-staining.

A long-bodied, long-eared, short-legged breed. Ectropion, inguinal hernia and glaucoma may be inherited conditions. Back problems caused by cervical spondylosis may occur, and failure of the anconeal process (elbow) to develop properly may be seen. Glaucoma is inherited by an unknown mechanism and THROMBOPATHIA by an autosomal dominant trait. GONIODYSGENESIS is also seen.

Bathing of animals may be undertaken for the sake of cleanliness, for the cure of a parasitic skin disease, or for the reduction of the temperature.

Cattle and sheep (See DIPS AND DIPPING.)

Dogs For ordinary purposes the dog is bathed in warm water, in which it is thoroughly soaked. It is then lathered with a suitable shampoo (many proprietary brands are available) or hard soap, rinsed off and dried. A wide range of specially formulated shampoos is available for specific skin conditions.

Dish-washing detergent liquid should not be used for shampooing puppies or even adult dogs.

Cats Because cats are fastidious creatures which wash themselves nearly all over (they cannot reach the back of their necks or between their shoulder blades), the question of bathing them does not arise except in cases of a severe infestation with external parasites; very old cats which have ceased to wash themselves; entire tom cats which as a result of stress or illness have also ceased to look after themselves; as a first-aid treatment for heat stroke/stress; and in some cases where a cat has fallen into a noxious liquid.

Shampoos/flea-killers, etc. sold for use on dogs are not all safe for cats. Owners should read the small print on packets and look for ‘safe for cats’ where a preparation has not been prescribed by a veterinary surgeon.

Baths are used to help the treatment of certain muscle and joint problems.

Chinchillas Sand baths are essential for chinchillas to keep their coats in good condition. Chinchilla sand should be similar to volcanic ash in the wild, with nine parts of Fuller’s earth to one part of sand. (Poultry perform dust bathing given the opportunity.)

An abnormally low positioning of the heart in the thorax.

An abnormally low position for the stomach.

Bating is the action performed by a bird of prey when it goes to fly suddenly from a perch to which it is tethered causing the leash to jerk it back towards the perch. This can result in injuries, especially a fracture of the tibiotarsal bone. Injuries can be minimised by the use of a very short leash.

A fungus responsible for a fatal dermatitis in FROGS and SALAMANDERS. The fungus may be due to hybridisation and it invades the skin and spores are released into ponds. Any pond with infected frogs will be infected and the infection only reaches other ponds by infected amphibians. Some frog species appear resistant including the South African Clawed Toad (Xenopus laevis) and the American Bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana) and may have spread to countries where these frogs have been traded.

(See also RABIES; VAMPIRE BATS; HISTOPLASMOSIS.) Bats are mammals, and usually produce one offspring in late spring or early summer. Fifteen species have been identified in Britain, where they are classified as protected creatures under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981. Bats can live for up to 30 years. They can die of EUROPEAN BAT LYSSA VIRUS (EBLV) which is like the rabies virus. In Canada, millions of bats have died from WHITE-NOSED SYNDROME, a fungal infection. All bats should be handled with care, using stout gloves to prevent being bitten.

A method of intensive egg production involving keeping hens in cages with a sloping floor, with 1, 2, or up to 5 birds per cage. Feeding and watering may be on the ‘cafeteria’ system, with food containers moving on an endless belt, electrically driven. The eggs are usually collected from racks at the front of the cages.

There have long been objections on welfare grounds to current battery systems and in January 2012 they were banned from the EU. Benefits achieved in good examples of battery cage systems (e.g. a smaller risk from parasites, good access to food and water) may be outweighed by their deficiencies (e.g. prevention of nesting behaviour, perching, dust-bathing; bone weakness caused by lack of freedom to move about).

From 1 January 2003 the permitted cage size was increased to allow a minimum of 550 cm2 per hen and since that date no new cages could be installed. ‘ENRICHED CAGES’, or alternative non-cage systems, were specified for new or replacement systems by 1 January 2002. The ‘enriched cages’ have 750 cm2 space per hen and provide a nest, litter to allow pecking and scratching, and perches. In the EU, battery cages were phased out by the end of 2011 with use of enrichment cages allowing more space per bird.

‘Cage layer fatigue’, a form of leg paralysis, is sometimes encountered in battery birds. Birds let out of their cages on to a solid floor usually recover. (See also INTENSIVE LIVESTOCK PRODUCTION; EGG YIELD.)

A battery rearing system has, in a somewhat different form, been applied to pig rearing.

A colour in horses which is tan or red-brown.

A French breed produced by crossing a white lop-eared Normandy pig with the black BERKSHIRE, it was used to help produce the PIÉTRAIN breed. It was believed to have become extinct in the 1960s. There are still pigs around that look like the Bayeux, but these are probably not purebred.

Infection with one or more species of parasitic helminths. The hosts are usually mammals (mainly mustelids). It infects the alimentary tract, but in hosts not naturally involved in the parasite’s life cycle, including man, the parasite may migrate into body tissues including the brain and eye. Baylisascariosis is an emerging zoonosis in North America.

BBSRC is the abbreviation for the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council which succeeded the Agricultural and Food Research Council in 1994. The main Institute of Animal Health laboratory is now centered at the Pibright Laboratory. (See AFRC.) The BBSRC Headquarters address is Polaris House, North Star Avenue, Swindon, Wiltshire SN2 1UH. Telephone: 01793 413200; website: www.bbrsc.ac.uk.

One of the two types of lymphocytes. They are important in the provision of immunity, and they respond to antigens by dividing and becoming plasma cells that can produce antibodies that will bind with the antigen. Their source is the bone marrow in mammals and the BURSA OF FABRICIUS in birds. It is believed that the function of B cells is assisted by a substance provided by T CELLS. With HAPTENS it is apparently the B cells which recognise the protein carrier, and the T cells which recognise the hapten. (See also LYMPHOCYTE; IMMUNE RESPONSE.)

BCG vaccine may be used for dogs and cats in Britain in households where a member of the household has tuberculosis. The vaccine does not cover every strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, however. Currently it cannot be used in cattle as it interferes with the tuberculin test, but trials show that it can assist in preventing infection. The vaccine has been licensed for immunising badgers. It has been used in the treatment of equine sarcoid.

(See BRITISH CATTLE VETERINARY ASSOCIATION.)

A breed of dog traditionally kept in packs. Behavioural problems may develop in solitary animals kept as pets. Inheritable conditions include primary and secondary CLEFT PALATES, CONGENITAL HAEMOLYTIC ANAEMIA, GLAUCOMA and EPILEPSY (sex-linked). A number of conditions which appear to be inherited in this breed but with an unknown mechanism of inheritance include EPIPHYSEAL DYSPLASIA, INTERVERTEBRAL DISC PROTRUSION and RETINAL DYSPLASIA. Conditions inherited as recessive traits include RENAL DYSGENESIS and RENAL AGENESIS. HAEMOPHILIA due to Factor VII (possibly autosomal dominant trait) and VIII deficiencies (sex-linked recessive trait) are reported. SPINA BIFIDA is inherited as a dominant trait and PULMONARY STENOSES are due to polygenic factors. There is also familial PYRUVATE KINASE DEFICIENCY in the breed.

(See DE-BEAKING; SHOVEL BEAK.)

A blunting of the end of the beak. In some cases it can be achieved by inserting an abrasive material (claw-shortening abrasive) in the bottom of the feed trough, which reduces any excess beak growth as the birds feed.

There are moves to phase out the practice, on welfare grounds. (See also DE-BEAKING.)

A breed of dog with a coat needing considerable attention. It is a long-lived breed at 13.7 years. Hip dysplasia has a multifactorial inheritance while HYPOADRENOCORTICISM (Addison’s disease) has an unknown inheritance mechanism.

The standard unit for measuring radiation. The quantity of radionucleotide that undergoes decay per second. (See RADIATION, EXPOSURE TO.)

Whenever animals are housed in buildings, it is both necessary and economical to provide them with some form of bedding material. The reasons are as follows:

1. All animals are able to rest more adequately in the recumbent position, and the temptation to lie is materially increased by the provision of some soft bedding upon which they may more comfortably repose than on the uncovered floor. Indeed there are some which, in the event of the bedding being inadequate, or when it becomes scraped away, will not lie down at all.

2. The provision of a sufficiency of some non-conductor of heat (which is one of the essentials of good bedding) minimises the risk of chills.

3. The protection afforded to prominent bony surfaces – such as the point of the hip, the points of the elbow and hock, the stifles and knees, etc. – is important, and if neglected leads to bruises and injuries of these parts.

4. From the point of view of cleanliness, both of the shed or loose-box and of the animal’s skin, the advantages of a plentiful supply of bedding are obvious.

5. In the case of sick animals, the supply and management of the bedding can aid recovery. (See also SLATTED FLOORS.)

Horses

Wheat straw Wheat straw undoubtedly makes the best litter for either stall or loose-box. Its main disadvantage is its inflammability.

Wheat straw should be supplied loose or in hand-tied bundles for preference. Trussed or baled straw has been pressed and has lost some of its resilience or elasticity in the process. The individual straws should be long and unbroken, and the natural resistive varnish-like coating should be still preserved in a sample. The colour should be yellowish or a golden white; it should be clean-looking and free from dustiness. Straw should be free from thistles and other weeds.

Wheat straw has a particular advantage in that horses will not eat it unless kept very short of hay.

Oat straw This straw is also very good for bedding purposes, but it possesses one or two disadvantages when compared with wheat straw. The straw is considerably softer, more easily broken and compressible than wheat and, being sweet to the taste, horses eat it.

Barley straw is inferior to either of the preceding for these reasons: it is only about half the length; it is very soft and easily compressed and therefore does not last as long as oat or wheat; more of it is required to bed the same-sized stall; and it possesses numbers of awns. The awns of barley are sharp and brittle. They irritate the softer parts of the skin, cause scratches, and sometimes penetrate the soft tissues of the udder, lips, nose, or the region about the tail.

Rye straw Rye straw has the same advantages as wheat straw, but it is a little harder and rougher.

Peat-moss Peat-moss is quite a useful litter for horses. It is recommended for town stables and for use on board ship, or other forms of transport. A good sample should not be powdery, but should consist of a matrix of fibres in which are entangled small lumps of pressed dry moss. It is very absorbent – taking up six or eight times its own weight of water. When it is used, the drains should be of the open or ‘surface’ variety or covered drains should be covered with old sacks, etc.

It should never be used in a loose-box in which there is an animal suffering from any respiratory disease, on account of its dusty nature.

Sand makes a fairly good bed when the sample does not contain any stones, shells, or other large particles. It is clean-looking, has a certain amount of scouring action on the coat, is cool in the summer, and comparatively easily managed. Sand should be obtained from a sand pit or the bed of a running stream; it should not be obtained from the seashore, because the latter is impregnated with salt, and likely to be licked by horses when they discover the salty taste of which they are very fond. If this habit is acquired the particles of sand that are eaten collect in the colon or caecum of the horse and may set up a condition known as ‘sand colic’, which is often difficult to alleviate. It is useful when a horse has COPD, as are wood shavings and sawdust.

Ferns and bracken make a soft bed and are easily managed, but they always look dirty and untidy, do not last as long as straws, and are rather absorbent when stamped down. With horses that eat their bedding there is a risk of bracken poisoning.

Cattle Wheat straw is the most satisfactory. Oat straw is used in parts where little or no wheat is grown. Barley straw is open to objection as a litter for cows on account of its awns, which may irritate the soft skin of the perineal region and of the udder. Sawdust has been found very convenient in cow cubicles, also shavings. Sand has been used on slippery floors below straw bedding, when it affords a good foothold for the cows and prevents accidents. Sand can cause blockage of slurry systems. (See also DEEP LITTER FOR CATTLE.) Special rubber mats have been found practicable and economic for use in cow cubicles. Shredded paper has been used for cattle (and also horses).

A disadvantage of sawdust is that its use has led to coliform mastitis (sometimes fatal) in cattle. This is caused by hardwoods, softwoods contain natural cresols. Sand may then be preferable.

In milk-fed calves, the ingestion of peat, sawdust or wood shavings may induce hypomagnesaemia.

Pigs Many materials are used for the pig, but probably none possesses advantages over wheat straw, unless in the case of farrowing or suckling sows. These should be littered with some very short bedding which will not become entangled round the feet of the little pigs, and will not irritate the udder of the mother. For this purpose chaff, shavings and even hay may be used according to circumstances.

Straw can make up for deficiencies in management and buildings as nothing else can. It serves the pig as a comfortable bed, as a blanket to burrow under, a plaything to avert boredom, and a source of roughage in meal-fed pigs which can help obviate digestive upsets and at least some of the scouring which reduces farmers’ profits. Straw can mitigate the effects of poor floor insulation, of draughts, and of cold; and in buildings without straw, ventilation (to quote David Sainsbury) ‘becomes a much more critical factor’.

As a newborn piglet spends so much of its time lying in direct contact with the floor of its pen, much body-heat can be lost through conduction. Depending on the type of floor, this effect can be large enough to affect the piglet’s growth rate and be a potential threat to its survival. Providing straw can be equivalent to raising the ambient temperature from 10° C to 18° C (50° F to 64° F). Wooden and rubber floors are not as effective as straw in reducing conductive heat loss.

Dogs and cats Dogs (and pigs) have died as a result of the use for bedding of shavings of the red African hardwood (Mansonia altissima), which affects nose, mouth, and the feet, as well as the heart.

Fatal poisoning of cats has followed the use of sawdust, from timber treated with pentachlorophenol, used as bedding.

Hamsters Synthetic bedding materials should be avoided as they can cause injury.

Poultry (See LITTER, OLD.)

Rabbits Peat-moss is recommended as it neutralises ammonia formed from urine; rabbits are particularly susceptible to ammonia in the atmosphere.

A small, soft-coated terrier with distinctive arched-back appearance. Together with some West Highland white terriers, they are prone to inherited copper toxicosis. The breed is relatively intolerant of high copper levels in the diet and may develop cirrhosis of the liver as a result. Zinc acetate has been used for treatment. Other inheritable conditions include brittle bones (OSTEOGENESIS IMPERFECTA) and RETINAL DYSPLASIA.

(See CHLAMYDOPHILA.)

The native British beef breeds are the Aberdeen Angus, Shorthorn Hereford, Devon, South Devon, Sussex, Galloway, Highland, Luing and South Devon. Continental breeds including the BELGIAN BLUE, BLONDE D’AQUITAINE, BROWN SWISS, CHAROLAIS, CHIANINA, GELBVIEHS, LIMOUSIN, PIEDMONTESE and SIMMENTAL have been imported for use in the United Kingdom. The continental breeds are more muscular, have higher mature weights and better performance than native breeds.

Most beef breed bulls are generally used as terminal sires on cows not required for breeding dairy herd replacements, and some beef cross heifers are used for suckler herd replacements. The cross-bred calves exhibit hybrid vigour and fetch a premium in the market over pure-bred dairy calves.

(See also CATTLE, BREEDS OF.)

Around 58 per cent of home-produced beef is derived from the dairy herd, partly from dairy-bred calves reared for beef and partly from culled dairy cows. A further 34 per cent comes from the beef suckler herd.

Store systems Cattle are usually on one farm for less than a year, typically a winter (yard finished) or summer period (grass finished), but sometimes as short a period as 3 months. Only part of the production cycle takes place on a single farm, the possibility for using a wide range of technical inputs is limited. The profitability is dominated by the relationship between buying and selling prices, and these systems are characterised by large year-to-year fluctuations in margins. As a generalisation, the longer the cattle are on the farm, the higher the margin. The animals are finished for beef elsewhere.

Evolved in the 18th century from Teeswater and Durham cattle, Shorthorns were originally dual-purpose (milk and meat) but the Beef Shorthorn herdbook started in 1958. The society allowed the introduction of MAINE-ANJOU CATTLE blood to improve muscling. (See DAIRY SHORTHORN CATTLE; SHORTHORN CATTLE.)

Honey bees (Apis spp.) represent one of the oldest forms of animal husbandry. There is only one species of honey bee in the UK and there is an annual loss 10 per cent - 30 per cent of colonies. Bumble bees have 23 UK species (Bombus spp.); they collect pollen and not nectar and have a more limited range than honey bees; solitary bees have over 200 UK species. Bees fertilise 87 crop species that form 35 per cent of world food production.

Modern beehives are designed so that the honey-filled combs can be removed and replaced without disturbing the main chamber, a practice that also minimises swarming. The Italian Yellow-Banded bee is a better ‘housekeeper’ than the honey bee and is sometimes used in hives, when hygiene is important. The introduction is made by placing combs of Italian bee larvae in the honey bee hive so that the Italian bees do the cleaning up. The colour of the honey bee and the introduced Italian bees is derived from how they are fed; both will therefore look the same although the new arrivals will keep their housekeeper characteristics. Improved pollination of fruit farms can occur by having small patches of native plants on farmed land to attract bees.

Bees are subject to several diseases of which VARROASIS is the most prevalent. The bee louse is seen as bees defaecate in the hive, although usually they excrete while on the wing. Colony collapse syndrome occurs in the USA and its cause is uncertain. Its presence in the UK is arguable. A University of Stirling study has shown that Neonicotinoid pesticides, used to protect major crops, can be harmful to bees. Thus, imidacloprid slowed spring population growth and reduced queen numbers. Thiamethoxam appeared to affect navigation ability of bees after foraging. A temporary two-year ban on use of NEONICOTINOIDS was introduced in the EU during 2013.

Other diseases include brood diseases (chalk brood, chilled brood, European foul brood, Sac brood [also known as addled brood or stone brood]), viral diseases, and protozoal diseases (amoebiosis, nosemosis [Nosema cerana, N. apis]). American foulbrood (caused by Paenibacillus bacterium) is a NOTIFIABLE DISEASE; infected hives must be destroyed and movement restrictions placed on bees and equipment from the apiary concerned. It was detected in an apiary in Perthshire, Scotland, and also found elsewhere. The infected hive was destroyed and movement restrictions placed on bees and equipment from the apiary concerned. European foul brood caused by Melissococcus plutonius can be rapidly detected by a gold nanoparticle test, although an atypical strain has been recorded.

The National Bee Unit, run by DEFRA, provides advice on bee health issues (National Bee Unit, The Food and Environment Research Agency, Sand Hutton, York YO41 1LZ. Telephone: 01904 462510; email: nbu@fera.gsi.gov.uk).

General advice can be obtained from the British Beekeeping Association (BBKA), National Beekeeping Centre, Stoneleigh Park, Kenilworth, Warks CV8 2LG. Telephone: 02476 690 682; email: bbka@britishbeekeepers.com.

(See also under BITES, STINGS AND POISONED WOUNDS.)

In poultry houses these insects in poultry houses have been shown to be reservoirs of avian reovirus, Newcastle Disease virus, Infectious Bursal Disease (Gumboro Disease) and Salmonella spp.

(See POISONING – Fodder poisoning.)

Breeding is based on 54 per cent polled Lincoln Red Blood, 40 per cent polled Beef Shorthorn, and 6 per cent Aberdeen Angus.

Antisocial, or inappropriate, behaviour in dogs and cats is an increasingly common problem. There are a number of possible causes, including genetic traits in particular breeds, hormonally triggered behaviour and intentional or unintentional mistreatment. The fact that many animals are left alone for long periods while their owners are at work can encourage misbehaviour. The animal becomes distressed during the periods of absence and may resort to urinating or defecating; or in the case of dogs, chewing furniture. Then over-excitement, with uncontrolled barking and jumping, results on the owner’s return. Aggressive behaviour to people or other animals is another common problem. Conversely, a pet may become obsessively attached to a single person, resenting any show of affection to that individual by another. While veterinary surgeons and ‘pet counsellors’ can offer advice on correcting unacceptable behaviour, it is greatly to be preferred that the problem is avoided in the first place.

When choosing a dog or cat, it is always advisable to see the puppy or kitten in its home environment. A pup from a litter born to a well-behaved bitch in a caring home is much more likely to develop into a good companion than a dog reared on a puppy farm with little opportunity to socialise with people. And one removed too early from its litter mates may later show aggression towards, or fear of, other dogs or cats. It also helps to avoid problems if a pet is selected that the owner can cope with easily. Big dogs need lots of space and lots of exercise; long haired breeds take a lot of grooming.

Punishment for ‘bad’ behaviour is rarely beneficial. Removing the cause, if possible, can help; rewarding for ‘good’ (correct) behaviour as part of a retraining process is more effective. Retraining requires patience and perseverance. The process may be assisted by the short-term use of medication. Megestrol (Ovarid) may be useful where the behavioural problem is hormonally triggered (spraying, aggression); or tranquillising drugs may be prescribed.

A beef breed noted for exceptional double hindquarter muscling. The British name is a misnomer, and it is now called BRITISH BLUE. DYSTOKIA may be a problem, in pure breeds and ones with Blue blood in them, partly due to a relatively narrow pelvis. Problems are much less in dairy type cattle, e.g. Holsteins. Maiden heifers should not become pregnant to a Belgian Blue bull or cows that have previously had dystokia after mating with Blue bulls.

It is a breed in which cataract can be inherited as a dominant trait. Hip dysplasia is multifactorial while in the Tervueren form of the breed, epilepsy may be inherited by an unknown mechanism.

Belladonna is another name for the deadly night-shade flower (Atropa belladonna). (See ATROPINE.)

A beef breed, often called ‘Belties’, it is a variety of Galloway with a distinctive wide white strip around the abdomen in both black and dun animals. They are often slightly smaller and more dairy-like than the main beef breed type. (See GALLOWAY CATTLE.)

A portmanteau name of Belgium and Texel; it is an offshoot of the Texel, with double muscling, used as a terminal sire for meat production. The breed entered Britain in 1989. They are polled and have no wool on the head or feet. The rams weigh about 90 kg (198 lb) and the ewes 70 kg (154 lb). Some ewes require CAESAREAN SECTION.

A central nervous system stimulant; may be used to counter barbiturate poisoning.

Benadryl is the proprietary name of beta-dimethylamino-ethylbenz-hydryl ether hydrochloride, which is of use as an antihistamine in treating certain allergic conditions. (See ANTIHISTAMINES.

A medicine for congestive heart failure in dogs and chronic renal insufficiency in cats. It is rapidly absorbed from the intestinal tract and forms benazeprilat which is a potent inhibitor of angio-tensin converting enzyme reducing the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II. The result is a reduction in vasoconstriction of arteries and veins, retention of sodium and water by the kidneys and remodelling of cardiac hypertrophy and degenerative renal changes.

A breed of cat developed from crossing the domestic cat (Felis catus) with the Asian wild cat (F. ornata). It is not considered as a hybrid between a wild animal and a domestic animal under the Dangerous Wild Animals Act 1976. The breed is prone to hip dysplasia and distal neuropathy. An anatomical anomaly described as ‘flat chest syndrome’ can also occur leading to breathing difficulties.

This is the area round the sea bed. Several benthic species of fish are farmed including the common sole, Dover sole and turbot. The last species lay 1,500,000 eggs at a time and so it requires only a few female fish to start a farm.

One of the quaternary ammonia compounds; it is used as an antiseptic and detergent. (See under QUATERNARY AMMONIUM COMPOUNDS.)

The gamma isomer of this (lindane) is a highly effective and persistent ectoparasiticide, which was formerly the main ingredient of several proprietary preparations, designed for use as dusting powder, spray, dip, etc. Its use in animals is now banned in many countries, including the UK, although the compound still keeps appearing in the environment and occasionally in animals. It is highly toxic for fish.

BHC is the common abbreviation for the gamma isomer. (See BHC POISONING.)

A family of pharmaceutical products used as anthelmintics used in the treatment of roundworms and, in some cases, fluke infestations in mammals, birds and reptiles. Examples include ALBENDAZOLE, FLUBENDAZOLE, MEBENDAZOLE, OXFENDAZOLE, and THIABENDAZOLE.

Benzocaine is a white powder, with local anaesthetic properties, used as a sedative for inflamed and painful surfaces and for general anaesthesia in fish.

Benzocaine-poisoning This has occurred in cats following use of either a benzocaine spray or ointment, and results in methaemoglobin appearing in the blood.

Signs In one case a cat showed signs of poisoning following an application of the cream to itchy areas. Cyanosis, open-mouthed breathing and vomiting occurred. Collapse followed within 15 minutes.

Improvement was noticed within 10 minutes of giving methylene blue intravenously; and within 2 hours breathing had become normal again. The cat recovered.

Benzoic acid is an antiseptic substance formerly used for inflammatory conditions of the urinary system. It is excreted as hippuric acid, and renders the urine acid. It is used in the treatment of ringworm, and as a food preservative.

Benzoic Acid Poisoning Cases of this have been reported in the cat, where benzoic acid was used as a food preservative, giving rise to extreme aggressiveness, salivation, convulsions and death. A curious sign sometimes observed is jumping backwards and striking out with the fore-limbs ‘as though catching imaginary mice’.

It is used in shampoos for dogs to control bacterial skin disease and seborrhoea.

Benzyl benzoate is a drug formerly used for treating mange in dogs and sweet itch in horses. A 25 per cent preparation may be applied to mite, etc., bites in pigeons.

Benzyl benzoate is usually employed as an emulsion. It should not be used over the whole body surface at once.

Bactericidal antibiotic, active against Gram-positive bacteria, and given by parenteral or intramammary infusion. It is inactivated by PENICILLINASE.

A drug which is used in sheep to kill Nematodirus worms.

They are said to be ‘Britain’s oldest pig breed’, being black pigs with white on the legs, faces and tips of the tail. They are early maturing and have a dished face, short legs and are of medium length. In Britain they are now a rare breed, and probably helped to develop the PIÉTRAIN breed.

A large, long-haired breed, mainly black with white with brown markings. Three inherited conditions have been recorded: primary and secondary CLEFT PALATES, HYPOMYELINOGENESIS and OSTEOCHONDROSIS but the mechanism is unknown and VON WILLEBRAND’S DISEASE. Also known as the Swiss mountain dog.

A French breed of heavy milking sheep. The breed contains some merino blood.

This is believed to be an essential trace element, but its role has not been determined. Fumes from industrial plants can contain beryllium and inhalation can result in pneumonia.

A protozoan disease usually affecting the skin and mucous membranes; other effects may include sterility. Not normally found in temperate countries but may appear following climate change.

These are pharmaceutical agents that bind on beta receptors on striated muscles (skeletal, heart) and smooth muscles (especially relaxing bronchial and uterine smooth muscle) as well as improving energy production. They mimic the actions of ADRENALIN and NORADRENALIN. There are two types: ß1 agonists such as adrenalin and ß2 agonists including salbutamol and CLENBUTEROL HYDROCHLORIDE. They are the opposite of beta-blockers. (See also RACTOPAMINE.)

(See AGONIST.)

A ketone body which can be measured in blood to determine the energy status. The higher the level, the poorer the energy intake. It is particularly of use in ruminants. It can be measured in milk with a cow-side test.

The name commonly used for trimethylglycine; it is present in many feed ingredients especially sugar beet pulp. Growing animals use much energy in maintaining osmotic balance in their alimentary tracts. Betaine can spare some of the energy, resulting in improved growth. Its presence may be the reason why sugar beet pulp is regarded as ‘nature’s blotting paper’ when treating diarrhoea.

Enzymes produced by bacteria which cause resistance to certain antibiotics (e.g. penicillins, cephalosporins) by breaking down the β-lactam ring.

A corticosteroid.

(See BRITISH EQUINE VETERINARY ASSOCIATION.)

One of the oldest and largest breeds of rabbit. Coat colour is blue, white, black, brown and lilac. The animals are docile, energetic and inquisitive so that they make good pets.

(See BETAHYDROXYBUTYRATE.)

(See BENZENE HEXACHLORIDE.)

This may arise, especially in kittens and puppies, from a single dose (e.g. licking of BHC-containing dusting powder). Signs include: twitching, muscular incoordination, anxiety, convulsions.

A farmer’s wife became ill (she had a convulsion) after helping to dip calves, but recovered after treatment. Two of the calves died.

BHC is highly poisonous for fish; it must be used with great care on cats (not used in UK), for which other insecticides such as selenium preparations are to be preferred.

The use of BHC sheep dips is no longer permitted in the UK.

Beta haemolytic streptococcus, a Gram-positive circular bacterium, naturally occurring in chain formation and causing red blood cells to lyse in the laboratory incubator. (See LYSIS.)

The current name for an organism previously known as Pasteurella haemolytica biotype T and then Pasteurella trehalosi. It is a Gram-negative pleomorphic rod particularly causing septicaemia in sheep. It has also been found in cattle where it forms part of the bovine respiratory disease syndrome. (See PASTEURELLOSIS IN SHEEP; BOVINE RESPIRATORY DISEASE COMPLEX; ENZOOTIC PNEUMONIA OF CALVES; ENZOOTIC PNEUMONIA OF PIGS; ENZOOTIC PNEUMONIA OF SHEEP.)

A salt containing HCO3; the amount in blood determines the acid/base balance. Sodium bicarbonate is used as an antacid in ruminal acidosis. A saturated solution is a useful DEMULCENT applied to the skin.

A breed of small white dog from Belgium, not unlike a miniature poodle, which has become popular in Britain in recent years. Cataract can be inherited by an unknown mechanism.

A cleft tongue.

Term used to describe osteodystrophia fibrosa in horses and goats caused by a calcium/phosphorus imbalance in the diet. (See BRAN DISEASE). In Australia it is attributed in horses to the ingestion of buffel, pangola, setaria, kikuyu, green panic, guinea and signal grass, which contain high levels of oxalate that chelates the calcium in the intestines and prevents adequate absorption, thereby eventually leading to osteofibrosis.

A condition associated with Clostridium novyi (type A) and other clostridial species infection in rams which have slightly injured their heads as a result of fighting. It occurs in UK, Australia and South Africa. (See also HYDROCEPHALUS.)

Occurring on two sides, having two sides. (See also UNILATERAL.)

Bile is a thick, bitter, golden-brown or greenish-yellow fluid secreted by the liver and stored in the gall-bladder, except in horses which do not have the organ. It has digestive functions, assisting the emulsification of the fat contents of the food. It has in addition some laxative action, stimulating peristalsis, and it aids absorption of fats and fat-soluble vitamins. (See CHOLECYSTOKININ.)

JAUNDICE or ICTERUS is a sign rather than a disease; it may be caused when the flow of the bile is obstructed and does not reach the intestines, but remains circulating in the blood or from haemolysis. As a result, the pigments are deposited in the tissues and discolour them, while the visible mucous membranes are yellowish.

Vomiting of bile usually occurs when the normal passage through the intestines is obstructed, and during the course of certain digestive disorders. (See also GALLSTONES.)

Steroid acids produced from the liver. The amount circulating in the blood can be measured in conjunction with other tests in an attempt to assess liver function.

Bilharziosis is a disease caused by bilharziae or schistosomes; these are parasites of about 0.25 cm to 1 cm in length which are sometimes found in the bloodstream of cattle and sheep in Europe, and of horses, camels, cattle, sheep, and donkeys in India, Japan and the northern seaboard countries of Africa. (See SCHISTOSOMIASIS.) Dogs may also suffer from these flukes.

(See CANINE BABESIOSIS; EQUINE BILIARY FEVER.)

A bile pigment circulating in blood; it is a breakdown product of the blood pigment haem.

A bile pigment that circulates in the blood of herbivores.

See BEAK, usually large.

Binovular Twins result from the fertilisation of 2 ova, as distinct from ‘monovular twins’ which arise from a single ovum.

The study of chemical reactions within the body.

A biocide destroys living organisms; sodium hypochlorite (bleach) is an example.

A layer of organic material adhering to the inner surfaces of pipes and equipment. It is an excellent material for bacterial growth and must be removed regularly to prevent this. Attention should also be paid in kennels where water is supplied by nipple drinkers. Flushing with 1.5 to 3.0 bars of pressure can dislodge it.

The emission of light by an organism, such as is seen in fireflies and some fish. It results from a chemical reaction which produces light with virtually no heat.

All the living organisms in a given area. In veterinary practice, the term is used to express stocking density as kilograms of live animals per square metre of floor space.

The study of physical actions within the body.

Biopsy is a diagnostic method in which a small portion of living tissue is removed from an animal and examined by special means in the laboratory so that a diagnosis may be made.

A term used to describe the precautions necessary on farms (and certain other establishments where animals are kept) to prevent disease entering and infecting the animals resident on the premises. It is achieved by controlling and minimising all movements of animals, animal products, people, transport, etc., onto the farm, and discouraging vermin and bird entry. Animals brought on the farm should be (as far as possible) of known origin and of a similar health status to those already present. They should have received vaccinations or other preventive treatments for any diseases present on the previous farm as well as those on the one to which they are moving. They should be quarantined before being exposed to some of the resident animals: ideally, old cull animals before the latter leave the farm, to ensure that the new entrants have experienced the pathogens present on the farm and also to check that the culls do not contract anything from the new entrants.

The application of biological knowledge, of micro-organisms, systems or processes to a wide range of activities, such as cheese-making, animal production, waste recycling, pollution control, and human and veterinary medicine. For the manipulation of genes, see GENETIC ENGINEERING.

The body established in 1994 which incorporates the work of the Agriculture and Food Research Council, and the Biotechnology Directorate and Biological Sciences Committee of the former Science and Engineering Research Council.

A water soluble vitamin of the B group; also known as vitamin H.

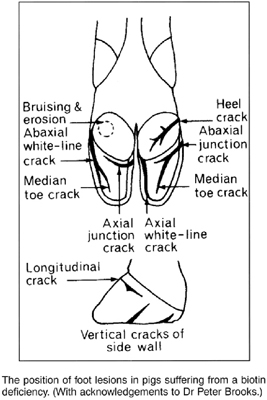

A deficiency of biotin is linked to foot problems, mainly associated with the hoof. The hoof horn in horses and cattle is believed to be strengthened by a biotin-rich diet; foot lesions in pigs (see illustration on previous page) may similarly benefit, as may ‘soft’ or diseased claws of dogs.

A group or strain of a micro-organism or species that has distinguishable physiological characteristics.

These are used where there is a loss of bone density to prevent the breaking down of bone.

Patients may be regarded as having bird-fancier’s lung if they satisfy all the following criteria: recent history of avian exposure; serum avian precipitins; diffuse shadowing on chest radiograph; a significant reduction (less than 70 per cent predicted value) of carbon-monoxide transfer factor (single breath); and improvement or no deterioration when exposure to birds and their excreta is ceased.

In some cases there have been changes in the intestine (villous atrophy).

In the acute form, most often seen in pigeon-fanciers after cleaning the loft, influenza-like signs, a shortness of breath and a cough occur after four to six hours. The disease in elderly patients has to be differentiated from bronchitis and emphysema.

Bird import controls were imposed in Great Britain in 1996, and a licence is required for all imports of captive birds and hatching eggs. All birds except those from Belgium are subject to a quarantine of 35 days. Birds imported into the EU are subject to quarantine. (See also PIGEONS.)

Bird louse is a parasitic insect belonging to the order Mallophaga, which attacks most domesticated and many wild birds. The lice eat feathers and the cells shed from the surface of the skin, but they do not suck blood. Dusting with parasiticide powder is an efficient remedy. A small cage bird affected with lice may be placed in a paper bag and dusted with insecticidal powder such as pybuthrin/piperonyl butoxide. (See LICE.)

A tropical disease of fowls and turkeys caused by Plasmodium gallinaceum, P. durae and other species, transmitted by mosquitoes.

It may run a rapidly fatal course, or a chronic one with anaemia and greenish diarrhoea.

(See under AVIAN; also CAGE AND AVIARY BIRDS, DISEASES OF; GAME BIRDS, MORTALITY; TURKEYS; POULTRY AND POULTRY KEEPING; ORNITHOSIS; BOTULISM; FALCONS, DISEASES OF; PETS, CHILDREN’S AND EXOTIC; RABIES; OSTRICH; RHEA.)

The toenail-clip method enables blood to be collected into a micro-haematocrit tube or pipette. The bird can be held with its back against the palm of the hand, head between thumb and forefinger, making sure the sternum is not impeded. The resultant sample may be contaminated with droppings and so the jugular vein is preferred. With a little practice, it is accessible even in small birds.

Larger cage birds have easily accessible jugular veins, the right side being larger than the left. In pigeons and doves (Columbiformes), the presence of a venous anastomosis makes attempts to puncture the jugular vein dangerous in these species. In raptors, fowl and pigeons, the brachial vein is favoured; the tarsal vein is preferred for blood sampling in water fowl.

For poultry and other birds, a lidless wooden box or chamber (of a size to take a polypropylene poultry crate) and a cylinder of carbon dioxide with regulating valve are useful. The box has a 1.3-cm (½ in) copper pipe drilled with 0.35-cm (9/64-in) holes at 10-cm (4-in) centres fitted at levels 5 cm (2 in) and 66 cm (2 ft 2 in) from the bottom and connected by plastic tubing to the regulator valve of the cylinder.

Birdsville disease occurs in parts of Australia, is due to a poisonous plant Indigofera enneaphylla, and has to be differentiated from Kimberley horse disease.

Signs Sleepiness and abnormal gait with front legs lifted high. Chronic cases drag the hind limbs.

Congenital deformity consisting of a double nose.

A foreign breed of short-hair cat. Degenerative distal polyneuropathy has been identified in this breed as an autosomal recessive trait.

A member of the family Birnaviridae, it is a non-enveloped virus containing two segments of double-stranded RNA. It causes INFECTIOUS BURSAL DISEASE and TRANSMISSIBLE VIRAL PROVENTRICULITIS in chickens and INFECTIOUS PANCREATIC NECROSIS in salmon and trout.

(See PARTURITION.)

An animal having both male and female sex organs. Many male freshwater fish in British river and lake waters are bisexual, a condition attributed to oestrogens in the water. The oestrogens are thought to have originated from oestrogens in the urine of women taking contraceptive pills.

Bismuth (Bi) is one of the heavy metals.

Uses The carbonate, subnitrate, and the salicylate may be used in irritable and painful conditions of the stomach and intestines; also to relieve diarrhoea and vomiting.

The oxychloride and the subnitrate are used like barium, in bismuth meals prior to taking X-ray photographs of the abdominal organs for purposes of diagnosis.

Large ruminant ungulates which are in the Bovidae Family. Two species survive, the American bison (Bison bison) and the European bison or WISENT (Bison bonasus). The American bison is also called the American BUFFALO. Both species are under threat with small numbers in the wild and there are captive breeding programmes in operation. They are used for meat.

A surgical knife used to open up stenosed (closed up) teats, fistulae, sinuses; and abscesses.

The bites of animals, whether domesticated or otherwise, should always be looked upon as infected WOUNDS. In countries where RABIES is present, the spread of this disease is generally by means of a bite.

TETANUS is always a hazard from bites.

Bees, wasps and hornets cause great irritation by the stings with which the females are provided. Death has been reported in pigs eating windfall apples in which wasps were feeding. The wasps stung the mucous membrane of the throat, causing great swelling and death from suffocation some hours later.