(See FELINE ADVISORY BUREAU.)

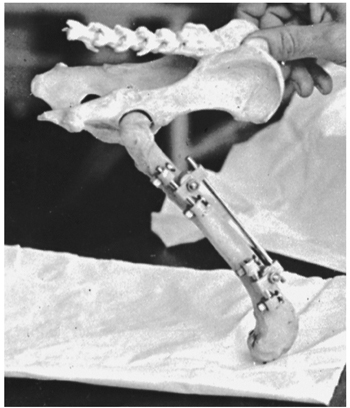

An operation in which a prosthetic ligament is inserted around the patellar ligament and the fabella to restabilise a stifle in which the cruciate ligament has been ruptured. (See CRUCIATE LIGAMENTS.)

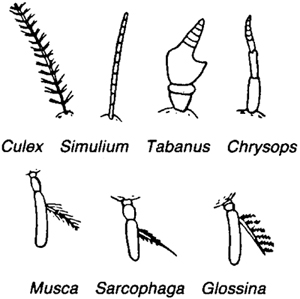

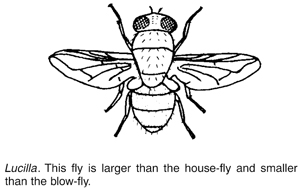

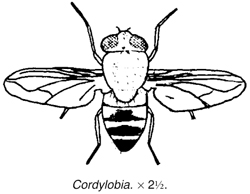

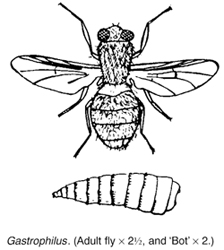

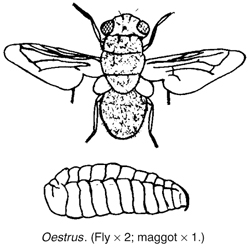

(See under FLIES.)

(See HOLOPROSENCEPHALY.)

A condition in the gerbil due to excessive secretion from the HARDERIAN GLAND. There is erythema, scabs and sometimes moist dermatitis around the nostrils that may become infected, leading to sinusitis.

Treatment: reduce humidity, provide a sand bath and, where groups are kept, reduce numbers. Topical treatment of the bacterial infection can be used, but systemic antibiotics may be required.

‘Facial eczema’ is a synonym for a form of dermatitis caused by light sensitisation in cattle and sheep. (See LIGHT SENSITISATION.)

The facial nerve is the seventh of the cranial nerves, a motor nerve that supplies the muscles of expression of the face.

In the case of unilateral ‘facial paralysis’, which very often follows accidents in which the side of the face has been badly bruised. The muscles on one side become paralysed but those on the opposite side are unaffected. This absence of antagonism between the two sides results in the upper and lower lips, and the muscles around the nostrils, becoming drawn over towards the unaffected side, and the animal presents an altered facial expression. The ear on the injured side of the head very often hangs loosely and flaps back and forward with every movement of the head, and the eyelids on the same side are held half-shut. MRI can be used to detect facial nerve abnormalities in dogs. (See also under GUTTURAL POUCH DISEASE; LISTERIOSIS.)

This is more correctly termed DERMATOGRAPHISM.

Smoke from these may contaminate pastures and cause disease in grazing animals. (See FLUOROSIS; MOLYBDENUM.)

‘Fading’ is the colloquial name for an illness of puppies, leading usually to their death within a few days of birth. Signs include: progressive weakness which soon makes sucking impossible; a falling body temperature; and ‘paddling’ movements. Affected puppies may be killed by their dams. Possible causes include canine viral hepatitis; another is a canine herpesvirus; a third may be a blood incompatibility; a fourth Bordetella; a fifth is hypothermia or ‘chilling’, in which the puppy’s body temperature falls. Another possible cause may be Clostridium perfringens infection.

Kittens A similar syndrome may be caused by the feline leukaemia virus.

A test used to detect ANTHELMINTIC RESISTANCE. It involves taking a faecal sample and counting the worm eggs, giving a dose of the anthelmintic and then taking a second faecal sample after a certain number of days depending on the anthelmintic used. The egg count remaining is counted.

(singular, Faex)

Excreta, excrement or the body waste removed from the ALIMENTARY CANAL via the RECTUM, moved by PERISTALSIS after its formation in the COLON. As the faeces build up in the rectum they stretch the rectal wall and stimulate nerves to signal the need to evacuate the contents. DEFAECATION occurs by relaxation of the sphincter muscles of the ANUS. In dogs, cats, some other animals and humans faeces are called STOOLS.

(See COPROPHAGY.)

The singular of FAECES.

Fainting fits (syncope) are generally due to cerebral anoxaemia occurring through compromised blood circulation, sudden shock, or severe injury. It is most commonly seen in dogs and cats, especially when old, but cases have been seen in all animals.

These are the smallest breed of horse. They must not be higher than 8.2 HANDS (82 cm) high, but they are usually between 7 hands (70 cms) and 8 hands (80 cms). They are mainly bay and black but spotted greys occur. They originate from Crillo stock from Argentina, with some SHETLAND PONY and WELSH PONY. There has been considerable INBREEDING to maintain the small size.

Falcons are the genus of birds Falco, a collective containing 37 species of wild bird. In Britain, the peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus) is the fastest bird on earth at 20 miles (320 km) an hour. Male falcons are called tercel (American tiercel) and the chicks, whilst in down, are called eyas. The female is larger than the male. In Britain, many falcons are kept for displays but they may be used for hunting, especially abroad. The red-tailed hawk (Bueo jamaicensis) or the Harris hawk (Parabuteo unicinctus) are popular.

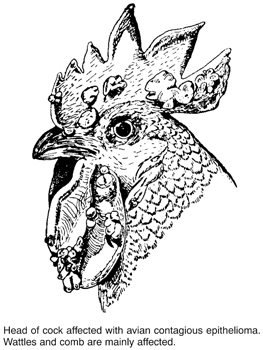

Avian pox has been found in imported peregrine falcons, giving rise to scab formation on feet and face and leading sometimes to blindness. Tuberculosis is not uncommon, and may be suspected when the bird loses weight. ‘FROUNCE’ and ‘inflammation of the crop’ are old names for a condition, caused by infestation with protozoan parasites (Tritrichomonas), which can be successfully treated. Frounce causes a bird to refuse food, or to pick up pieces of meat and flick them away again, swallowing apparently being too painful; there is also a sticky, white discharge at the corners of the beak and in the mouth. CAPILLARIA are found in the oropharynx or intestines of infected birds and can be treated with FENBENDAZOLE, ‘sour crop’ results in a swollen crop with foul smell containing meat and due to delay in emptying. Unless rapidly treated surgically under ANAESTHESIA there is rapid COLLAPSE, TOXAEMIA and death. ENTERITIS can be due to bacteria, viruses, fungi, endoparasites or toxins, COCCIDIOSIS (due to Caryospora spp.) occurs. TICKS feed on the birds.

ASPERGILLOSIS is a common cause of weight loss and even death in captive falcons. Bone fractures may arise as a result of calcium deficiency through birds being fed a bone-free all-meat diet. This may be prevented by sprinkling sterilised bone meal or oyster shell on the meat, or feeding the bird with small rodents. BATING, while tethered, can also cause leg fractures. BUMBLE-FOOT is another cause of lameness.

In the Middle East, dosing falcons with ammonium chloride – a common, if misguided, practice believed to enhance their hunting qualities – has caused sickness and fatalities.

Hawks experience similar problems but BUMBLE-FOOT is a more serious problem.

These, one on each side, run from the extremity of the horns of the uterus to the region of the ovary.

Cats fall from windows of high-rise buildings when chasing birds, insects, etc. and sustain fractures of the mandible and hard palate as the chin hits the ground.

Dogs fall less commonly, but when they do, they sustain injuries to face, chest and extremities, with spinal injuries occurring when they fall from over two storeys high.

(See under PSEUDO-PREGNANCY.)

A condition which can cover many types of kidney problems which have a familial basis. It occurs in FINNISH LANDRACE SHEEP and in some breeds of dogs such as COCKER SPANIELS.

A group of diseases that cause dysfunction in the proximal renal tubules and then affect fluid reabsorption. The affected animal’s urine contains glucose, amino acids, sodium, phosphorus and uric acid. There is also metabolic acidosis. It is seen as an inherited form in BASENJIS.

In buildings that are ventilated artificially, it is mandatory under the Welfare of Farmed Animals Regulations 2007 (England and Wales) to have an alarm and stand-by system in order to prevent heat-stroke or anoxia. (See CONTROLLED ENVIRONMENT HOUSING.)

(See FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION.)

Local application of an electric current as a passive exercise which stimulates muscles and nerves.

The form of GLANDERS affecting the body and limb surfaces. It is usually chronic in horses.

In the UK it is illegal for the castration of horses, donkeys, mules, dogs or cats to be carried out without an anaesthetic. (See ANAESTHETICS, LEGAL REQUIREMENTS; CASTRATION.) Only a veterinary surgeon is permitted to castrate any farm animal more than two months old, with the exception of rams, for which the maximum age is three months.

Only veterinary surgeons are permitted to carry out a vasectomy or electro-ejaculation of any farm animal; likewise the de-snooding of turkeys over 21 days old, de-combing of domestic fowls over 72 hours old, and de-toeing of fowls and turkeys over 72 hours old. Nor can anyone but a veterinary surgeon remove supernumerary teats of calves over three months old, or disbud or dishorn sheep or goats.

Certain procedures legal overseas are prohibited in the UK, namely freeze-dagging of sheep, penis amputation and other operations on the penis, tongue amputation in calves, hot branding of cattle and the de-voicing of cockerels. Very short DOCKING of sheep is also prohibited in the UK.

(See VETERINARY FACILITIES ON THE FARM.)

This committee took over from the FARM ANIMAL WELFARE COUNCIL on 1 April 2011. It is an expert committee of the DEPARTMENT FOR ENVIRONMENT, FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS and the devolved administrations of Scotland and Wales. Address: FAWC Secretariat, Area 8B, 9 Millbank, c/o 17 Smith Square, London SW1P 3JR. Telephone: 0207 238 5124/ 6340/ 5016; email: fawcsecretariat@defra.gsi.gov.uk.

An independent body set up by the government in 1979 to keep under review the welfare of farmed animals. Farms, markets, abattoirs and vehicles were inspected and, where appropriate, recommendations made to government. Reports were issued from time to time on the welfare of particular species or aspects (transport, slaughter, etc.) of the use of farm animals. This Council closed in March 2011 and was superseded by the Farm Animal Welfare Committee.

A scheme undertaken by one of several independent organisations which periodically visit farms and provides an overview of the farm, its management, and welfare and disease standards. It is undertaken in the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia, some parts of the USA and other countries. It can in some ways be considered an extension of the HACCP principle onto farms. It involves areas of BIOSECURITY, and TRACEABILITY. Most responsible traders including supermarkets will usually only purchase food from farms and processors where there is farm assurance.

(See SPRAYS USED ON CROPS; FERTILISERS; METALDEHYDE POISONING.)

A disease caused by the inhalation of dust, from mouldy hay, etc., containing spores of e.g. Thermopolyspora polyspora or Micropolyspora faeni. Localised histamine release in the lung produces oedema, resulting in poor oxygen uptake. It is classed as an acute extrinsic allergic alveolitis. Repeated exposure causes respiratory distress, even when the interval between exposures is several years. The condition has been recognised in humans, cattle, horses and turkeys. In chickens, a similar condition has been caused by inhalation of dust from dead mites in sugar cane bagasse (fibrous residues).

(See WORMS.)

A person who shoes horses. Farriery is a craft of great antiquity and the farrier has been described as the ancestor of the veterinarian. In the UK, farriery training is strictly controlled. Intending farriers must undergo a five-year apprenticeship, including a period at an authorised college, then take an examination for the diploma of the Worshipful Company of Farriers before they can practise independently. The training is controlled by the Farriers Training Council and a register of farriers kept by the Farriers Registration Council.

Address: Sefton House, Adam Court, Newark Road, Peterborough PE1 5PP; Telephone: 01733 319911; email: frc@farrier-reg.gov.uk; website: www.farrier-reg.gov.uk.

The act of parturition in the sow.

A rectangular box in which the sow gives birth. Their use is helpful in preventing overlying of piglets by the sow, and so in obviating one cause of piglet mortality; however, they are far from ideal. Farrowing rails serve the same purpose but perhaps the best arrangement is the circular one which originated in New Zealand. (See ROUNDHOUSE.)

Work at the University of Nebraska suggests that a round stall is better, because the conventional rectangular one does not allow the sow to obey her natural nesting instincts, and may give rise to stress, more stillbirths and agalactia.

(See MASTITIS METRITIS AGALACTIA SYNDROME.)

In the sow, the farrowing rate after one natural service appears to be in the region of 86 per cent. Following a first artificial insemination, the farrowing rate appears to be appreciably lower, but at the Lyndhurst, Hants AI Centre, a farrowing rate of about 83 per cent was obtained when only females which stood firmly to be mounted at insemination time were used. The national (British) average farrowing rate has been estimated at 65 per cent for a first insemination. Australian research has shown that the quality of feed given to gilts from about 10 weeks will affect the number of eggs shed as an adult. In the USA feeding more energy and less protein has increased the chances of a sow having more than four pregnancies.

Sheets or bands of fibrous tissue which enclose and connect the muscles.

Infestation with liver flukes.

Normal body fat is, chemically, an ester of three molecules of 1, 2 or 3 fatty acids, with 1 molecule of glycerol. Such fats are known as glycerides, to distinguish them from other fats and waxes in which an alcohol other than glycerol has formed the ester. (See also LIPIDS [which include fat]; FATTY ACIDS. For fat as a tissue, see ADIPOSE TISSUE). There are two types of fat – brown fat and white fat. Brown fat is seen particularly in young animals and is used to provide body heat on exposure to cold. White fat is metabolised following SYMPATHETIC NERVOUS SYSTEM stimulation releasing NORADRENALIN and is used for movement. White beige fat is an intermediate fat type derived from white fat with the properties of white and brown fat but is used less efficiently than either. A LIPOMA is a benign fatty tumour. For other diseases associated with fat see STEATITIS; FATTY LIVER/KIDNEY SYNDROME OF CHICKENS AND TURKEYS; OBESITY, DIET AND DIETETICS.

These accumulations of fat in the caudal COELOM of reptiles constitute their normal fat stores. Reptiles do not have subcutaneous fat deposits or an OMENTUM. Fat bodies should not be confused with fatty tumours (See LIPOMA).

Found in fat and also called ADIPOCYTES.

Seen in cats. (See EOSINOPHILIC GRANULOMA.)

(See EXERCISE; MUSCLE; NERVES.)

Fats protected from rumen degradation are digested lower in the gut and serve as a concentrated energy source. They can also improve milk and meat production and increase conjugated linoleic acid.

In poultry rations these can lead to ‘TOXIC FAT SYNDROME’. (See LIPIDS for cattle supplement; also ECZEMA in cats.)

These, with an alcohol, form FAT. Saturated fatty acids have twice as many hydrogen atoms as carbon atoms, and each molecule of fatty acid contains two atoms of oxygen. Unsaturated fatty acids contain less than twice as many hydrogen atoms as carbon items, and one or more pairs of adjacent atoms are connected by double bonds. Polyunsaturated fatty acids are those in which several pairs of adjacent carbon atoms contain double bonds. Certain fatty acids, e.g. linoleic acid, are known as ‘essential’ and are necessary for coat health. There may be species differences; for example, skin ulceration can be presented by fatty acid supplementation in the black rhinoceros, but they are not required in the white rhinoceros.

Omega-3 fatty acids appear to have a beneficial effect on heart muscle, but need to be balanced with omega-6 fatty acids as the latter can have a deleterious effect. In humans, conjugated linoleic acid has anti-carcinogennic effects, improves food digestibility and reduces body fat deposition.

Butyric acid can help inhibit infection of the mucous membranes by Salmonella and Campylobacter spp. and so reduce human food-borne illness.

A condition in which there is an excess of fat in the parenchyma cells of organs such as the liver, heart and kidneys.

This is a condition in laying hens which has to be differentiated from FLKS (see next entry) of high-carbohydrate broiler-chicks. Factors involved include high carbohydrate diets, high environmental temperatures, high oestrogen levels, and the particular strain of bird. FLHS in hens is improved by diets based on wheat as compared with maize; whereas FLKS is aggravated by diets based on wheat. Death is due to haemorrhage from the enlarged liver.

A condition in which excessive amounts of fat are present in the liver, kidneys and myocardium. The liver is pale and swollen, with haemorrhages sometimes present, and the kidneys vary from being slightly swollen and pale pink to being excessively enlarged and white. Morbidity is usually between 5 per cent and 30 per cent. It can be caused by many factors, including genetics, diet, management, hormones, environment and toxic substances. A similar condition is seen in cage birds that receive diets high in fats and carbohydrates and do not exercise.

Prevention FLKS has been shown to respond to biotin (see VITAMINS), and accordingly can be prevented by suitable modification of the diet.

Signs A number of the more forward birds (usually two to three weeks old) suddenly show signs of paralysis. They lie down on their breasts with their heads stretched forward; others lie on their sides with their heads bent over their backs. Death may occur within a few hours. Mortality seldom exceeds 1 per cent.

A ‘production disease’ which may occur in high-yielding dairy cows immediately after calving. It is then that they are subjected to ‘energy deficit’ and mobilise body reserves for milk production. This mobilisation results in the accumulation of fat in the liver, and also in muscle and kidney. In some cases the liver cells become so engorged with fat that they actually rupture.

An important consequence of this syndrome may be an adverse effect on fertility. Cows with a severe fatty liver syndrome were reported to have had a calving interval of 443 days, as compared with 376 days for those with a mild fatty liver syndrome.

Complications such as chronic ketosis, parturient paresis (recumbency after calving), and a greater susceptibility to infection have been also been reported.

The only sign may be wattles paler than normal; the birds remain apparently in good condition. The cause may be varied – genetic, nutritional, management, environmental, and presence of toxic substances. Adding choline, vitamins E and B12, and inositol to the diet can remedy the condition. Reducing the metabolisable energy level in the diet by about 14 per cent usually prevents it.

Fauces is the narrow opening which connects the mouth with the throat. It is bounded above by the soft palate, below by the base of the tongue, and the openings of the tonsils lies at either side. Faucitis is inflammation of the tissues around the opening and may occur in isolation or form part of a more generalised stomatitis.

(See ACETONAEMIA; ACIDOSIS; KETOSIS; NUTRITION, FAULTY; FEED BLOCKS; DIET AND DIETETICS; LAMENESS in cattle; BLINDNESS.)

Faulty wiring of farm equipment has led to cows refusing concentrates in the parlour, not because they were unpalatable (as at first thought), but because the container was live so that cows wanting to feed were deterred by a mild electric shock. (See also EARTHING; ELECTRIC SHOCK, ‘STRAY VOLTAGE’ AND ELECTROCUTION.)

A dual-purpose breed originating from France. They are large birds, good layers, and were considered as possibly contributing to broiler breeder genes. Cocks weigh 3.5 kg (8 lb) and hens 3 kg (6.5 lb). They have five toes and feathered shanks. The plumage of hens is mainly brown and creamy-white and cocks have black, brown and straw-coloured feathers. Their eggs are brown.

Favus is another name for ‘honeycomb ringworm’. (See RINGWORM.)

Abbreviation of FARM ANIMAL WELFARE COUNCIL. (See FARM ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE.)

(Feathering; adjective, Feathered)

Long hairs on the fetlocks of draught horses and some ponies. In dogs, feathering is seen on the ventral surface of the body, the caudal aspect of the legs and the ventral tail of spaniels and setters.

An inherited problem particularly of budgerigars and parrots thought to be due to a single recessive gene. Abnormal feathering is seen as soon as they start to feather up and the flight, tail and contour feathers continue to grow. Most birds die at 10 to 12 weeks but they can survive two or more years. Affected birds should not be bred from. It is also known as ‘Chrysanthemum disease’.

Feather picking (feather pulling) in poultry and in cage birds, particularly parrots, may be due to boredom or insecurity.

Poultry In many cases it is due to the irritation caused by lice or to the ravages of the depluming mite. In such cases the necessary anti-parasitic measures must be taken. Insufficient animal protein in the diet of young growing chicks, especially when kept under intensive conditions, may cause the vice. Once the birds start pulling the feather they sooner or later draw blood, and an outbreak of cannibalism results. Treatment consists of isolating the culprit, if it can be found at the beginning, and of feeding the birds a balanced diet containing green food. The addition of blood meal in the mash is effective in many cases. The use of blue glass in intensive houses has stopped the habit in some cases. Use of trees in free-range pens reduces feather-pecking.

Parrots In parrots the syndrome is much more complex and triggered by many factors. Feather pecking is never seen in birds in the wild. The condition is diagnosed by the fact that the affected bird has a fully-feathered head and the wings, legs and body are deplumed as only they can be reached by the beak. The condition has to be thoroughly investigated: often there is an underlying disease, and response to appropriate treatment resolves the feather picking. Specific treatment varies from the application of an ELIZABETHAN COLLAR to the administration of psychotic drugs, but sometimes environmental changes have been effective – e.g. the transference of a caged bird to an aviary or the provision of a CONSPECIFIC individual for company.

An anthelmintic used for the treatment of parasitic gastroenteritis and parasitic bronchitis in cattle, sheep, pigs and horses and in combination with PYRANTEL and PRAZIQUANTEL for the control of intestinal worms in dogs. Chemically, febantel is a pro-benzimidazole which is converted in the body to benzimidazole.

An organisation representing veterinary organisations in 38 European countries and with four sections representing practitioners, hygienists, veterinary state officers and veterinarians in education, research and industry. Address: Avenue de Tervuren 12, B-1040 Brussels, Telephone: (00) 32 2533 70 20; E-mail: info@fve.org

The European Federation of Animal Health, an association of veterinary medicine manufacturers.

(See ADDITIVES.)

These ‘self-help’ lick blocks, placed out on pasture, are useful especially on hill farms for preventing loss of condition and even semi-starvation in the ewe.

Most feed blocks contain cereals as a source of carbohydrate, protein from natural sources supplemented by urea, minerals, trace elements and vitamins. In some blocks glucose or molasses is substituted for the cereals as the chief source of carbohydrate. A third type contains no protein or urea but provides glucose, minerals, trace elements, and vitamins; being especially useful in the context of hypomagnesaemia (and other metabolic ills) in ewes shortly before and after lambing.

Their effectiveness for providing specific ingredients is variable as animals differ in the extent to which they use feed blocks.

The gain in weight, in kg or lb, produced by 1 kg or 1 lb of feed; it is the reciprocal of the feed conversion ratio.

If FCRs are to be used as a basis of comparison as between one litter and another, or one farm’s pigs and another’s, it is essential that the same meal or other foods be used; otherwise the figures become meaningless.

The amount of feed in kg or lb necessary to produce 1 kg or 1 lb of weight gain.

(See DIET AND DIETETICS; FAULTY NUTRITION.)

Feed must be stored separately from fertilisers, or contamination and subsequent poisoning may occur.

The safe storage period on the farm of certain feeds is given under DIET AND DIETETICS.

Poultry and rats and mice must not be allowed to contaminate feeding-stuffs, or SALMONELLOSIS may result. If warfarin has been used, this may be contained in rodents’ urine and lead to poisoning of stock through contamination of feeding-stuffs. (See also TOXOPLASMOSIS.)

Unsterilised bone-meal is a potential source of salmonellosis and anthrax infections.

(See also ADDITIVES; CONCENTRATES; DIET AND DIETETICS; MITES, PARASITIC - OTHER MITES - FORAGE MITES; MOULDY FOOD; MYCOTOXICOSIS; CUBES AND PELLETS; SACKS; LUBRICANTS.)

Feeding-Stuffs Regulations 2000 control the constituents of animal feed including pet food. They specify, among other items, permitted additives, colourants, emulsifiers, stabilisers, maximum amounts of vitamins and trace elements, and permitted preservatives.

Feedlots involve the ZERO-GRAZING of beef cattle on a very large scale. In the USA there are some feedlots of 100,000 head each, and many more containing tens of thousands of cattle. Veterinary problems arise when these cattle are brought to the feedlot from range or pasture, and fed on grain. Shipping fever is a common ailment; likewise liver abscesses.

Related to, or of, the Family Felidae including the domestic cat (Felis catus).

A charity in the UK dedicated to promoting the health and welfare of cats through improved knowledge. It provides information for those involved in veterinary care, rescue work and boarding establishments as well as the general cat-owning public. After 55 years the name was changed in 2013 to INTERNATIONAL CAT CARE. (See also INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY OF FELINE MEDICINE.)

(See ANAEMIA; TOXOPLASMOSIS; HAEMOBARTONELLA; FELINE LEUKAEMIA; FELINE BABESIOSIS.)

(See FELINE DYSAUTONOMIA (KEY-GASKELL SYNDROME).)

An uncommon parasitic disease of cats due to infestation of erythrocytes with Babesia felis causing anaemia, lethargy and sometimes jaundice. Young cats may develop immunity to Babesia felis without prior signs of illness; older cats often have recurrent illness. Subclinical infections occur. The disease can prove fatal. (See also BABESIOSIS.)

A disease of the upper respiratory tract of cats involving Bordetella bronchiseptica. Clinical signs can be mild, but fatal pneumonia can develop especially in kittens. Some animals may become symptomless carriers of the organism (which is also responsible for respiratory disease in other species, including kennel cough in dogs). Treatment is by antibiotics.

Infection with calicivirus (of which there are several strains) is an important cause of FELINE INFLUENZA (‘CAT FLU’). Signs include fever, discharge from the eyes and nose and ulcers of the mouth and tongue. The virus is disseminated by sneezing cats, through contact with nasal secretions picked up on the hands and clothing of attendants, etc. Calicivirus is also associated with chronic stomatitis, a limping syndrome and a virulent systemic form associated with high mortality.

Cancer is an important disease of cats. Cancer of the lymph nodes is common, as is that of the bone marrow. Skin cancer and mammary gland cancers also occur. (See also under CANCER.)

Clinical signs of this heart condition include dyspnoea, weight loss and lethargy. Diagnosis is by radiography. Beta blockers, digitalis and diltiazem have been used in treatment. The cause is unknown.

An acute upper respiratory disease caused by Chlamydiophila felis; also known as feline pneumonitis.

Signs Severe swelling and redness, nasal discharge, sneezing and coughing. It commonly affects groups of animals, rarely single cats. Treatment includes topical and/or systemic antibiotics. Chlamydiosis vaccine (available as a combination product) protects against clinical disease but not infection.

It is seen as ocular hyperaemia and/or CHEMOSIS. Causative agents are feline herpes virus-1 (FHV-1), Chlamydophila felis, Mycoplasma felis or Gram-negative bacteria. Diagnosis is best confirmed by PCR. Treatment of FHV-1 involves the use of topical anti-viral agents such as acyclovir, or famciclovir given orally – these products are not licensed for cats in the UK. Treatment of Chlamydophila and Mycoplasma is best achieved with a tetracycline such as doxycycline.

This is a common infection in cats that usually causes mild, often asymptomatic, infections, but it may progress to FELINE INFECTIOUS PERITONITIS (FIP).

Gum and tooth diseases are quite common in cats. (See MOUTH, DISEASES OF; TEETH.)

Resorption of the teeth by the body is common in domestic cats. This may occur as (usually) painful cavities at the gum line (often hidden by a flap of gum) or painless root resorption. (See MOUTH, DISEASES OF.)

(See under DIABETES MELLITUS.)

A condition in cats first recognised at Bristol University’s department of veterinary medicine in 1981–2. It is also called feline autonomic polygangliopathy.

Signs include depression, loss of appetite, prominent nictitating membranes, dry and encrusted nostrils – suggesting a respiratory disease. Constipation and a transient diarrhoea have both been reported; also incontinence in some cases. The pupils are dilated and unresponsive to light and tear production is diminished. There may be difficulty in swallowing and food may be regurgitated. A common finding is enlargement of the oesophagus (MEGAOESOPHAGUS). Lesions include loss of nerve cells, and their replacement by fibrous tissue, in certain ganglia. The disease is similar to GRASS SICKNESS in horses. The cause is still unknown.

Treatment involves countering dehydration, maintaining nutritional status through assisted feeding, use of eye drops to encourage nasal and tear secretions and using laxatives to encourage bowel movements.

Prognosis The recovery rate is stated to be about 25 per cent, but recuperation may take weeks or months. Cats with a greatly enlarged oesophagus, persistent loss of appetite, or bladder paralysis are the least likely to survive.

(See also CANINE DYSAUTONOMIA.)

An uncommon infection affecting the blood cells of cats that is likely to be spread by ticks. Several Ehrlichia species have been implicated. The commonest findings are fever, malaise and gastroenteritis, but the respiratory system and joints may also be affected. Tick repellents help prevent infection; treatment is usually with TETRACYCLINES.

This has been reported in Sydney, Australia, and is characterised by non-fatal cases of hind-leg ataxia, and sometimes by side-to-side movements of head and neck. On post-mortem examination, demyelinating lesions and perivascular cuffing involving the brain and spinal cord were found. The cause is thought to be a virus, but efforts to transmit the disease have failed.

Hair loss that usually occurs on the posterior aspects of the hind-limbs and along the belly and back. Often associated with flea infestation (see ECZEMA), it may respond to control of the parasite and administration of steroids.

Conjunctival swabs from cats with conjunctivitis and from clinically normal cats were examined microbiologically. Non-haemolytic streptococci and Staphylococcus epidermis were isolated from both groups while beta-haemolytic streptococci, rhinotracheitis (feline herpes 1) virus, Mycoplasma felis and Chlamydophilia felis were isolated from cases with conjunctivitis.

This can be mild and transient. Sometimes the term is applied not to an inflammation of the gums but merely to a hyperaemia – an increased blood flow – which ‘may alarm the owner but does not hurt the (young) cat’.

Gingivitis can also be acute or chronic, easily treatable, or highly intractable.

One of the commonest causes of gingivitis in middle-aged or elderly cats is the accumulation of tartar on the surface of the teeth. If neglected, the tartar will gradually encroach on to the gums, causing these to become inflamed. Unless the tartar is removed, a shrinkage of the gums is likely to follow. As the gum recedes from the teeth it leaves pockets or spaces into which food particles and bacteria can lodge, exacerbating the inflammation, causing halitosis and leading to the roots of some teeth becoming infected.

The yellowish tartar deposits can become so thick and extensive that eventually they completely mask the teeth. A cat in this condition undoubtedly suffers much discomfort, finds eating a little difficult, and may have toothache. Health is further impaired by the persistent infection. The cat becomes dejected.

Even in such advanced cases, removal of the tartar (and of any loose teeth) can bring about almost a rejuvenation of the animal.

This form of chronic gingivitis can be successfully overcome by treatment and, indeed, prevented if an annual check of the teeth is carried out by a veterinary surgeon.

Intractable gingivitis Some cases of this are associated with a generalised illness rather than merely disease of the mouth. For example, chronic kidney disease, and possibly diabetes, may cause ulcers on the gums (as well as elsewhere in the mouth).

Some strains of the feline calicivirus may also cause gum and tongue ulceration. Bacterial secondary invaders are likely to worsen this, especially if the cat’s bodily defence systems have been impaired by, say, the feline leukaemia virus, some other infection, or even stress.

Antibiotics or sulphonamides are used to control the bacteria; vitamins prescribed to assist the repair of damaged tissue and to help restore appetite, and other supportive measures taken. However, some cases of feline gingivitis do not respond.

It is likely that all the causes of feline gingivitis have not yet been established. Further research will no doubt bridge the gaps in existing knowledge, and bring new methods of treatment and a better prognosis. (See also FELINE STOMATITIS.)

This is not a very common condition in cats, mainly seen in males but does involve haemophilia A, haemophilia B and haemophilia in MAINE COON cats. There are varying degrees of haemorrhage usually following trauma, HAEMATOMAS may develop, or bleeding into joints. Prolonged bleeding following any surgery may be the first indication that the animal is affected.

This is caused by an autosomal recessive gene; the signs are progressive ataxia in infancy, and the condition appears linked to an abnormal coat colour.

One of the causes of feline influenza. Infection may occur in combination with feline calicivirus. Clinical signs may be severe and include epiphora, coughing, dyspnoea and corneal ulcers. Secondary bacterial infection can lead to fatal pneumonia. Cats recovering from acute infection may be left with chronic nasal and ocular disorders; they will also become carriers of the virus. Infection is spread by sneezing, and may be carried on equipment, clothing, hands of attendants, etc. (See FELINE VIRAL RHINOTRACHEITIS; FELINE INFLUENZA.)

An uncommon condition reported in cats, mainly within Europe and initially described in Switzerland in 2000. Usually there are sudden behavioural changes with AGGRESSIVENESS and SEIZURES with no response to treatment. Diagnosis is indicated by the signs and history and used of MRI findings. The cause is not yet known and so the condition is often described as Feline Idiopathic Hippocampal Necrosis.

(See HYPERTHYROIDISM.)

The most commonly acquired heart condition in cats. It is seen at any age, either sex (although common in middle-aged males) and breed (common in Persians). Cats may show laboured breathing after exercise, look depressed, have low appetite, and may show tachycardia, heart murmur, or abnormal rhythm. If undetected it can lead to pulmonary oedema and arterial THROMBOSIS.

Cystitis of unknown cause but which can be improved by increasing water consumption, stress reduction, environmental enrichment and modification, and paying attention to an individual cat’s needs in a multi-cat household.

Formerly known as the feline T-lymphotropic lentivirus (FTLV). It was discovered in California by N. C. Pedersen and colleagues. Spread by the saliva of infected cats, or less often via the milk or placenta, it has a prolonged incubation period leading to permanent infection.

The virus establishes a permanent infection; the prognosis is poor. Clinical signs can be transient and mild – fever, depression, enlarged lymph glands. As the virus causes immunosuppression, secondary infections account for many of the clinical signs.

Diagnosis is confirmed by laboratory demonstration of antibodies. Treatment is aimed at control of secondary infection by antibiotics; many cases, however, end fatally.

This disease is caused by the bacterium Mycoplasma haemofelis (formerly classified as Haemobartonella felis). It is treated with antibiotics. Blood transfusions or fluid therapy may be required in severe, acute cases.

Adult cats may carry the parasite, the disease lying dormant until some debilitating condition (e.g. stress or immunosuppression) lowers the cat’s resistance. (See HAEMOTROPIC ANAEMIA.)

Signs are those associated with anaemia: loss of appetite, lethargy, weakness and loss of weight. Anaemia may be severe enough to cause panting.

Diagnosis may be confirmed by identifying the causal agent in blood smears or testing for bacterial DNA.

This was formerly called feline distemper. The disease is caused by a parvovirus. Cats of all ages are susceptible; survivors appear to acquire lifelong immunity. The disease is less common than it was, as a result of successful vaccination programmes.

Cause The virus is indistinguishable from mink enteritis virus, resistant to heat and many disinfectants, and can survive outside its host for over a year. It causes severe damage to the bowel and bone marrow.

Signs Kittens and young unvaccinated cats are most at risk although non-immune cats of any age are susceptible. In susceptible cats the only sign may be sudden death, but more usually the virus causes an acute enteritis associated with fever, loss of appetite, vomiting, bloody diarrhoea with rapid dehydration and death. In newborn kittens infected in the uterus, the CEREBELLUM may be affected giving rise to a staggering gait.

Disease may be less severe in cats that are immune due to previous vaccination or exposure to infection.

Diagnosis may be confirmed by laboratory tests – examination of bone marrow and blood smears. Post-mortem examination reveals inflammation of the ileum, oedema of the mesenteric lymph nodes and liquefaction of the bone marrow. The disease must be differentiated from poisoning, toxoplasmosis, intestinal foreign bodies and septicaemia.

Prevention Live and inactivated vaccines are available; live vaccines, however, are not suitable for use in pregnant queens.

Treatment Supportive measures to counter dehydration and shock and potentially overwhelming secondary bacterial infections. Even though the bowel is often severely compromised, nutritional support is essential. In a cattery, isolation of in-contact animals and rigid disinfection must be practised. (See also NURSING OF SICK ANIMALS.)

A slowly progressive and fatal disease of young cats, and sometimes of older ones also, caused by a coronavirus. Although the coronavirus is commonly found in cats, most do not develop the disease. Where FIP develops, it usually does so in a ‘wet’ form in which fluid accumulates in the body cavities. A ‘dry’ form also occurs. It is the cat’s own immune response to the virus that determines which form of the disease is likely to be present.

Clinical signs in the early stages are non-specific. Fever, depression, loss of appetite, gradual loss of weight, distension of the abdomen due to fluid. Occasionally, diarrhoea and vomiting occur.

There may be distressed breathing in the ‘dry’ form. Inflammation within tissues can cause damage to organs such as the liver, kidneys, eyes, and brain. Both forms are fatal although some individuals with the ‘dry’ form may survive for many months. Confirmation of a diagnosis of FIP can be strongly suggested on clinical examination but confirmation depends on tissue biopsy or post-mortem examination. Treatment with recombinant feline INTERFERON omega (rfIFN-ω) reduces viral infection.

Prevention is difficult where cats are grouped together as the virus is very infectious. Some catteries try to control infection by repeated antibody testing and isolation techniques combined with stringent hygiene. Where queens are known to be a possible source of infection to their kittens, isolating the queen before kittening and early weaning into a clean environment provides a good method of producing virus-free kittens. A vaccine is available in some countries but its use is controversial.

The name is loosely applied to respiratory infections involving more than one virus, known as the feline viral respiratory disease complex. It commonly occurs in cat-breeding and boarding establishments, the infection(s) being highly contagious. Feline calicivirus and feline herpes virus (feline rhinotracheitis) are commonly involved but other infectious agents such as Bordetella bronchiseptica and Chlamydophila can create very similar signs. Secondary bacterial invaders account for many of the more serious signs.

Signs Sneezing and coughing. The temperature is usually high at first; the appetite is depressed; the animal is dull; the eyes are kept half-shut, or the eyelids may be closed altogether; there is discharge from the nose; condition is rapidly lost. If pneumonia supervenes the breathing becomes very rapid and great distress is apparent; exhaustion and prostration follow. Diagnosis is confirmed by isolation of the virus from nasal swabs by a specialist laboratory.

Treatment Isolation of the sick cat under the best possible hygienic conditions is immediately necessary. There should be plenty of light and fresh air, and domesticated cats need to be kept fairly warm.

Antibiotics help to control secondary bacterial infection. Food should be highly palatable and easily digested. (See NURSING OF SICK ANIMALS; PROTEIN, HYDROLISED.)

Owing to the very highly contagious nature of the viruses causing feline influenza, disinfection after recovery must be very thorough before other cats are admitted to the premises.

Prevention Live attenuated combined vaccines against feline viral rhinotracheitis and feline calicivirus are available. Vaccines are generally effective, but as there are several strains of feline calicivirus, they may not protect against them all. Other controls include strict hygiene (of premises and attendants) and the segregation of carrier (infected) cats.

Feline juvenile osteodystrophy is a disease, of nutritional origin, in the growing kitten.

Cause A diet deficient in calcium and rich in phosphorus; kittens fed exclusively on minced beef or sheep heart have developed the disease within eight weeks. As the use of proprietary diets has increased, then the condition has become less common.

Signs The kitten becomes less playful and reluctant to jump down even from modest heights; it may become stranded when climbing curtains owing to being unable to disengage its claws. There may be lameness, sometimes due to a greenstick fracture; pain in the back may make the kitten bad-tempered and sometimes unable to stand. In kittens which survive, deformity of the skeleton may be shown in later life, with bowing of long bones, fractures, prominence of the spine of the shoulder blade, and abnormalities which together suggest a shortening of the back.

This is a cause of ulcers, and small, palpable swellings under the skin. The disease is transmissible to human beings. (See LEISHMANIASIS.)

Formerly thought to be caused by M. lepraemurium; now shown to be caused by several MYCOBACTERIA that cause leprosy in rats. It has been assumed that most infection of cats was from rats. The skin shows nodules with or without hair, mainly on the head and limbs and occasionally the body. Some reports include lesions of the mouth and the conjunctiva. Disease progress is related to the infective dose and the ability of the host to establish an immunity.

A disease of cats caused by a virus (FeLV) discovered by Professor W. F. H. Jarrett in 1964. The virus gives rise to cancer, especially lymphosarcoma involving the alimentary canal and thymus, and lymphatic leukaemia. Anaemia, glomerulonephritis, and an immunosuppressive syndrome may also result from this infection, which can be readily transmitted from cat to cat. Many cats are able to overcome the infection. The virus may infect not only the bone marrow, lymph nodes, etc., but also epithelial cells of mouth, nose, salivary glands, intestine and urinary bladder.

Kittens of up to four months of age are more likely to become permanently infected with FeLV than older cats, but many cases do occur in cats over five years old.

Many cats which have apparently recovered from natural exposure to the virus remain latently infected, but keep free from FeLV-associated diseases. Such cats may infect their kittens via the milk.

Significance of FeLV Most deaths of FeLV-positive cats are not directly attributable to this virus, but to other viral, bacterial or protozoal infections which are rendered far more serious because of the immunosuppression caused by the virus.

Signs These vary and may be vague, with a gradual loss of condition, poor appetite, depression and anaemia; or they may be related to immunosuppression such as stomatitis or chronic diarrhoea. The cancer induced by FeLV may create enlarged lymph nodes leading to breathing difficulties or enlarged abdominal organs.

Diagnosis FeLV infection can be confirmed by detecting viral protein or genetic material in blood samples using techniques such as ELISA tests, immunofluorescence and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays. Viral isolation can also be performed. Healthy cats that test positive should always have follow-up testing as false positives can occur with some of these tests.

Control It is possible to spread the FeLV infection from infected cats whether sick or currently healthy. This can be a problem if the infected cat lives with other cats or goes outside. This can be prevented by a ‘test-and-removal’ system. Infected cats are removed for euthanasia, and any other cats in the same household are then tested. If FeLV-positive, they too are removed, even if clinically healthy. Retesting of the FeLV-negative cats is necessary after three and six months. If still FeLV-negative, they can be considered clear, and new cats introduced on to the premises, if desired.

The virus may persist in the bone marrow of cats which have ostensibly recovered. Such a latent infection can be reactivated by large doses of corticosteroid; the virus can be recovered by cultivation of bone marrow cells. FeLV is not transmitted from cats with a latent infection.

Inactivated vaccines will not protect cats that are already infected and no vaccines are 100 per cent effective.

Formerly called FELINE UROLOGICAL SYNDROME (FUS). The name is given to the several conditions causing painful and difficult URINATION, often with blood-stained urine. It may also be associated with changes in behaviour and URINATION habits. In cases that lead to obstruction of the URETHRA it can, if untreated, lead to death. In many cases the cause is unknown and is referred to as FELINE IDIOPATHIC CYSTITIS (FIC). Less commonly, bladder stones (calculi), the formation of sand-like material, cancer and bacterial infections can cause the signs of FLUTD. In those cats that develop URETHRAL OBSTRUCTION, it is usually males as the URETHRA is longer and narrower than in females, the cause in IDIOPATHIC cases is due to the formation of urethral plugs. These are composed of varying proportions of STRUVITE and organic matter.

Cause Various theories have been advanced to account for FLUTD: possible contributory factors include as yet unidentified infectious agents such as a virus or viruses, dry diets and poor water intake, and a high level of magnesium in the diet. The effects of heredity and castration have also been mentioned. However, it is now recognised that STRESS can be an important factor. Certain types of cat are recognised to be predisposed on account of their inability to cope with stressful situations such as the presence of other cats in the same household or the outside environment. Stress can trigger inflammation of the bladder wall (CYSTITIS) via nerve pathways, but factors from within the bladder itself can also trigger this nerve-induced (NEUROGENIC) inflammation compounding the problem. Feline dry diets are now formulated to maintain urine at the correct degree of acidity to avoid the problem.

Signs The cat may be seen straining to pass urine, with only very little to be produced. The urine may be bloodstained. Cat-owners sometimes mistake FLUTD for constipation; straining may also be seen with CYSTITIS, when the bladder is usually empty, and when the URETHRA is blocked and so the bladder is full. Other signs include loss of appetite, dejection, and restlessness. The abdomen will be painful to the touch, owing to distension of the bladder.

NB: URETHRAL OBSTRUCTION is an emergency requiring immediate veterinary attention, in default of which there is a great risk of collapse and unconsciousness. The bladder may rupture, causing additional shock, and leading to PERITONITIS.

Treatment If a cause of FLUTD is identified it should be treated appropriately. Often, however, the disease is likely to be multifactorial. In acute cases anti-inflammatory medication and pain relief is indicated. In the case of a blocked urethra, skilled manipulation can sometimes free a urethral plug. If this fails, a catheter will have to be passed to empty the bladder; this is imperative to relieve the back pressure on the kidneys. If CATHETERISATION fails, it will be necessary to empty the bladder by means of direct aspiration (cystocentesis).

Prognosis There are cases in which, after removal of the urethral obstruction, it does not recur. However, FELINE IDIOPATHIC CYSTITIS cases are prone to relapse and in cats with obstructed urethras repeated blockages are common. In these cases specialised surgical procedures or ultimately EUTHANASIA may be advisable. (See also INTERSTITIAL CYSTITIS.)

Post-operative treatment includes antibiotics and urine acid-alkali balance control in an attempt to dissolve the remaining crystals. A low-magnesium, urine-acidifying diet, including TAURINE, is also recommended and proprietary preparations are on sale to meet this requirement. (See PRESCRIPTION DIETS.)

(See ECZEMA.)

A skin condition caused by Mycobacterium lepraemurium of mice and possibly M. tuberculosis. These are ACID-FAST ORGANISMS. Any skin lesion containing acid-fast bacteria should be considered a potential public heath hazard. If there is no public health risk, the lesion may be treated by incising the area and then dosing with enrofloxacin. Unlicensed dapsone and clofazimine have been used under the ‘CASCADE’. (See also MYCOBACTERIUM.)

A condition caused by stress and/or anxiety resulting in excessive licking of the skin. Any ectoparasites need to be eliminated, before megestrol acetate or anti-stress drugs such as phenobarbitone and diazepam are used.

(See FELINE INFECTIOUS ENTERITIS.)

(See TEETH, DISEASES OF, TEETH - NECK LESIONS IN CATS’ TEETH; FELINE INFECTIOUS ENTERITIS.)

(See FELINE CHLAMYDIAL INFECTION.)

A high-grade FIBROSARCOMA occurring at sites traditionally used for vaccination in cats and reports started to appear 1991. Cases still occur despite changes in vaccine formulation and in feline vaccination protocols.

This was formerly thought to be cowpox virus. It is characterised by moist reddened lesions of the skin that may become scabby and purulent. Treatment is with disinfectant shampoos, and by creams to areas not accessible to licking; corticosteroids are contraindicated.

(See PYOTHORAX.)

A painful sunburn caused by cats sleeping with their feet or ears pointing to the sun. Ultraviolet light barrier creams have been used to prevent it.

This is similar clinically to BOVINE SPONGIFORM ENCEPHALOPATHY (BSE). The first signs are hypersensitivity to noise and visual stimuli. Ataxia follows and eventually the cat will not be able to get up. The cause is believed to be the eating of material from cattle affected by BSE. In a zoo, two pumas and a stray cat which shared their food were fed on split bovine heads. Both pumas and the cat died from FSE. At the height of the BSE outbreak in the 1990s in the UK, one case of FSE was being reported every six weeks.

Inflammation of the cat’s mouth.

Causes Various, including several viruses.

Signs These include difficulty in swallowing, halitosis, excessive salivation, loss of appetite and sometimes bleeding.

Treatment The aim is to limit secondary bacterial infection by means of antibiotics. A supplement of vitamins A, B and C may help. If the cat will not eat, subcutaneous fluid therapy will be required.

Chronic stomatitis in elderly cats may be due to EOSINOPHILIC GRANULOMA, or malignant growths such as squamous cell CARCINOMA or FIBROSARCOMA. (See also MOUTH, DISEASES OF.)

(See FELINE IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS.)

This is of unknown aetiology, but may be immune-mediated. It causes painless non-pruritic swellings of the soles of the feet. Often they resolve without treatment; otherwise corticosteroid creams are used.

(See FELINE LOWER URINARY TRACT DISEASE.)

The name given to a condition in which head-tilt, ataxia, nystagmus and, occasionally, vomiting were seen. Duration of signs was short, only up to 24 hours.

Feline viral rhinotracheitis is involved in the feline viral respiratory disease complex (FELINE INFLUENZA). The disease was discovered in the USA to be caused by a HERPESVIRUS, and first recorded in Britain in 1966. Severe signs are usually confined to kittens of up to six months old. Sneezing, conjunctivitis with discharge, coughing and ulcerated tongue may be seen. Bronchopneumonia and chronic sinusitis are possible complications.

Cause A herpesvirus. Infection may occur in a latent form, and a possible link has been suggested between this virus and feline syncytia-forming virus.

Live and inactivated vaccines are available against feline calicivirus and feline herpesvirus which may be implicated in the infection.

Treatment May include the use of a steam vaporiser, lactated Ringer’s solution to overcome dehydration and antibiotics. Vitamins and baby foods may help.

An odourless sulphur-containing amino acid present in cat urine which degrades to chemicals producing the characteristic ‘catty smell’.

These strong, useful ponies originated from Cumbria, England. They are normally black, with no white markings, and have FEATHERED legs. They are susceptible to FOAL IMMUNODEFICIENCY SYNDROME (originally called FELL PONY SYNDROME).

(See FOAL IMMUNODEFICIENCY SYNDROME.)

A country term used to describe ‘SUMMER MASTITIS’. As the quarter affected is usually non-productive after infection, it probably refers to “stealing the quarter”.

(See FELINE LEUKAEMIA.)

In the male dog this may occur as the result of a SERTOLI-CELL TUMOUR of a testicle.

Femur is the bone of the thigh, reaching from the hip-joint above to the stifle-joint below. It is the largest, strongest, and longest individual bone of the body. The bone lies at a slope of about 45 degrees to the horizontal in most animals when they are at rest, articulating at its upper end with the ACETABULUM of the pelvis, and at its lower end with the tibia. Just above the joint surface for the tibia is the patellar surface, upon which slides the patella, or ‘knee cap’.

Fractures of the head of the femur are common. Surgical repair may be possible.

A benzimidazole anthelmintic used in cattle, sheep, camelids, horses, pigs, poultry, dogs and cats. (See WORMS, FARM TREATMENT AGAINST.)

An analgesic for use in small mammals (rabbits, ferrets, guinea pigs, rats and mice). In horses long-term relief can be provided by application of fentanyl patches. It is usually combined with FLUANISONE for use as a neuroleptoanalgesic.

A herb used mainly in dog and cat remedies to stimulate appetite. In the USA it was used in a calf feed produced by one company and became habit forming so the animals would only eat feeds containing it. It was ruled in court that the herb had to be withdrawn.

Carbohydrates in the feed of pigs are sometimes fermented with lactobacilli to produce lactic acid and thereby suppress salmonellae and coliform multiplication.

Ferns other than bracken occasionally cause poisoning in cattle. For example, Dryopteris filix-mas (male fern) and D. borreri (rusty male fern) give rise to blindness, drowsiness and a desire to stand or lie in water. Poisoning is occasionally fatal. (See also BRACKEN POISONING.)

(Mustela putorius furo) These attractive creatures are increasingly popular as pets and about 20 per cent are working ferrets. They need careful and expert handling – a bite to the finger can penetrate to the bone. In the UK the breeding season begins in March and continues until the end of August. There is seasonal weight variation with weight loss in the spring and weight gain in the autumn. It is preferable that females (‘jills’ – males are ‘hobs’) not used for breeding are spayed. Unmated jills may be in oestrus for the whole of the breeding season, with the occurrence of persistently high levels of oestrogen. This can cause severe health problems, including a possibly fatal PANCYTOPENIA. Surgical neutering is a major cause of adrenal gland disease with progressive body ALOPECIA and PRURITUS. The alternatives to spaying are injections of proligestone, given via the scruff of the neck, or mating with a vasectomised male. The latter will result in a pseudo-pregnancy lasting about 42 days; the jill may need to be mated again if she returns to oestrus.

Other diseases of ferrets include HYPOCALCAEMIA, three to four weeks after giving birth; MASTITIS; ALEUTIAN DISEASE; CANINE DISTEMPER (often fatal with respiratory and gastrointestinal signs, vaccination prevents this); BOTULISM (type C); abscesses; enteritis due to E. coli or campylobacter. A CROHN’S DISEASE-like condition occurs. Ferret systemic CORONAVIRUS is an emerging fatal disease first recorded in USA in 2002. Skin tumours are not uncommon. Periodontal disease is often caused by the accumulation of dental calculus. UROLITHIASIS can occur; the ferret can be fed the cat food formulated to prevent this condition. Ferrets are susceptible to zinc poisoning and any galvanised material can be a risk.

Common external parasites include FLEAS, OTODECTES, SARCOPTIC MANGE (see MITES, PARASITIC), and TICKS. IMIDACLOPRID can be used to treat. Internal parasites include COCCIDIOSIS (Eimeria furo, E. ictidea, Isospora laidlawii), CRYPTOSPORIDIOSIS, GIARDIASIS (Giardia duodenalis), TOXOPLASMOSIS. Worm (HELMINTH) infestations include HEARTWORMS (Dirofilaria immitis), HOOKWORMS (Ancylostoma spp.), TAPEWORMS (Dipylidium caninum) and ROUNDWORMS (Toxocara spp.; Toxascaris leonina). Laboratory parameter reference ranges can be found in Veterinary Record (2012) 171 218, and there is a website dealing with health and management of ferrets at www.wildlifeinformation.org.

Ferritin is a form in which iron is stored in the body. Ferritin concentrations in serum are closely related to total body iron stores, and ferritin immunoassays can be used to assess the clinical iron status of human beings, horses, cattle, dogs, and pigs.

(See REPRODUCTION.)

Fertilisers should not be stored near feeding-stuffs, as contamination of the latter, leading to poisoning, may occur. Deaths can occur after cattle gain access to the remains of a fertiliser dump, often caused by a crust of superphosphate and ammonium sulphate that remained on the ground.

For the risk associated with unsterilised bone-meal, see under ANTHRAX and SALMONELLOSIS.

Hypomagnesaemia is frequently encountered in animals grazing pasture which has received a recent dressing with potash. (See also BASIC SLAG; FOG FEVER.)

(See CONCEPTION RATES; FARROWING RATES; INFERTILITY; CALVING INDEX.)

In New Zealand and the USA, a severe hind-foot lameness of cattle has been attributed to the grazing of Festuca arundinacea, a coarse grass which grows on poorly drained land or on the banks of ditches, and being tall stands out above the snow. In typical cases, the left hind-foot is affected first, and becomes cold, the skin being dry and necrotic. Signs appear 10 to 14 days after the cattle go on to the tall-fescue-dominated pasture. Ergot may be present, but is not invariably so.

It has been suggested that ‘fescue foot’ may be associated with a potent toxin, butenolide, produced by the fungus Fusarium tricinctum.

Adjective derived from FETUS, which is the unborn developing offspring after the embryonic stage.

Examples of these are TOXOCARA infection in bitches and TOXOPLASMOSIS in utero of cows, ewes, sows, bitches and cats.

(See CHORION; AMNION; ALLANTOIS; also UTERUS, DISEASES OF and EMBRYOLOGY.)

(See MUMMIFICATION OF FETUS.)

The joint in the horse’s limb between the metacarpus or metatarsus (cannon bones) and the 1st phalanx (long pastern bone). At the back of this joint are situated the sesamoids of the 1st phalanx. (See BONES.)

(See EMBRYOTOMY.)

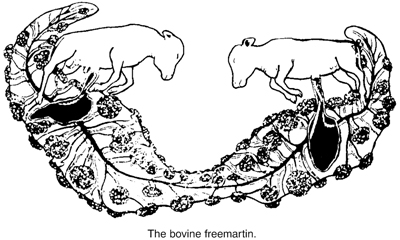

The young growing in the uterus after the organs have been formed. The word is from the Latin fetus, meaning offspring; the spelling ‘foetus’ is common, but incorrect. For an outline description of the development of the fetus, see under EMBRYOLOGY. For fetal circulation, see the diagram under CIRCULATION OF BLOOD. (See also FREEMARTIN.)

Fever is one of the commonest signs of infectious disease, and serves to make the distinction between febrile and non-febrile ailments. In true fever the body’s own in-built thermostat changes to a higher setting and the core temperature is raised accordingly. It is thought to be beneficial in many cases of infectious disease in countering the infective agent. Fever is a common sign in problems other than infectious disease, such as immune-mediated disease, pain and cancer especially in dogs and cats.

Examples of specific fevers are BLACK-QUARTER, BRAXY, DISTEMPER, EQUINE INFLUENZA and SWINE FEVER.

When fever reaches an excessively high stage, e.g. 41.5° C (107° F), in the horse or dog, the term ‘hyperpyrexia’ (excessive fever) is applied, and it is regarded as indicating a condition of danger; while if it exceeds 42° C or 42.5° C (108° F or 109° F) for any length of time, death almost always results. Occasionally, in certain fevers or febrile conditions, such as severe heat-stroke, the temperature may reach 44.5° C (112° F). (See also under TEMPERATURE, BODY.)

Signs Animals with a fever are usually depressed, lethargic and have a reduced appetite. They may appear stiff and reluctant to move and have mildly elevated respiratory and/or heart rates. There is usually a certain amount of shivering, to which the term ‘rigor’ is applied, but this is very often not noticed by the owner. Later, there may be PERSPIRATION, rapid breathing, a fast, full, bounding pulse, and a greater elevation of temperature are exhibited. Thirst is usually marked; the appetite disappears; the urine is scanty and of a high specific gravity; the bowels are generally constipated, although diarrhoea may follow later; oedema of all the visible mucous membranes, i.e. those of the eyes, nostrils, mouth, occurs. (See also HYPERTHERMIA.)

Fever may sometimes have a beneficial effect.

Experiments with newborn mice show that fatal infection with Coxsackie B1 virus can be modified to a subclinical infection if the animals are kept in an incubator at 34° C (93° F) and thus attain the same body temperature as mice of eight to nine days old. Similarly, puppies infected with canine herpesvirus survive longer and have diminished replication of virus in their organs if their body temperature is artificially raised to that of adult dogs. It is also said to assist in treating MYXOMATOSIS in rabbits.

The term used for the structural parts of plants which are commonly called DIETARY FIBRE or ROUGHAGE. It forms an important part of nutrition and feeding animals. Much of this cannot be digested by CARNIVORES or man, but is able to be partially utilised by HERBIVORES. (See also DIETARY FIBRE; DIET AND DIETETICS; HORSES, FEEDING OF; RATIONS FOR LIVESTOCK.)

Animals that require fibre as a major part of their diet. RABBITS, GUINEA PIGS and CHINCHILLAS in the wild live on grass, plants, twigs and bark.

An involuntary contraction of individual bundles of muscle fibres.

Fibrin is a substance upon which depends the formation of blood clots. (See CLOTTING OF BLOOD; PLASMA.)

Fibrin is found not only in coagulated blood, but also in many inflammatory conditions. Later it is either dissolved again by, and taken up into, the blood, or is ‘organised’ into fibrous tissue.

A high molecular weight protein in solution in the blood plasma also known as Clotting Factor 1, which following the action of thrombin is converted to fibrin and this is precipitated to form part of the process of clotting. Concentration of this is increased in inflammatory conditions, especially lesions of serous surfaces and in ENDOCARDITIS. (See also CLOTTING OF BLOOD.)

It breaks down FIBRIN by enzymatic action such as blood clots.

An irregularly-shaped cell responsible for the synthesis of CONNECTIVE TISSUE.

It is a mixture in varying proportions of white FIBROUS TISSUE and CARTILAGE. It tends to be white in colour, and the fibrous tissue provides strength and toughness and cartilage provides elasticity.

This is the protrusion of an intervertebral disc which has degenerated and enters the spinal canal, causing damage of the blood vessels and resulting in restriction of the blood supply (ISCHAEMIA) and damage of the SPINAL CORD (MYELOPATHY). The signs are sudden in onset, do not progress and are often asymmetrical and involve varying degrees of paralysis and loss of, or poor pulse in, the limbs. It is particularly seen in middle-aged dogs of large breeds, and also is common in horses.

(See TUMOURS.)

A tumour arising from fibrous or CONNECTIVE TISSUE; always malignant and often highly invasive.

The formation of fibrous tissue, which may replace other tissue. (See also CIRRHOSIS.)

Fibrous tissue is one of the most abundant tissues of the body, being found in quantity below the skin, around muscles and to a lesser extent between them, and forming tendons to a great extent; quantities are associated with bone when it is being calcified and afterwards, and fibrous tissue is always laid down where healing or inflammatory processes are at work. There are two varieties: white fibrous tissue and yellow elastic fibrous tissue.

White fibrous tissue consists of a substance called ‘collagen’ which yields gelatin on boiling, and is arranged in bundles of fibres between which lie flattened, star-shaped cells. It is very unyielding and forms tendons and ligaments; it binds the bundles of muscle fibres together, is laid down during the repair of wounds, and forms the scars which result; it may form the basis of cartilage; and it has the property of contracting as time goes on so may cause puckering of the tissues around.

Yellow fibrous tissue is not so plentiful as the former. It consists of bundles of long yellow fibres, formed from a substance called ‘elastin’, and is very elastic. It is found in the walls of arteries, in certain ligaments which are elastic, and the bundles are present in some varieties of elastic cartilage. (See ADHESIONS; WOUNDS.)

One of the bones of the hind-limb, running from the stifle to the hock. It appears to become less and less important in direct proportion as the number of the digits of the limb decreases. In the horse and ox it is a very small and slim bone which does not take any part in the bearing of weight; while in the dog it is quite large, and with the tibia, takes its share in supporting the weight of the body.

(See FELINE IDIOPATHIC CYSTITIS.)

A vulnerable breed. They are black coated and popular for hunting. They were bred into a taller type; all are single coloured, including black, dark brown (liver) or roan.

Ficus carica contain cellulase, xylanase and gluconase and dried fig mean is used in the tropics to improve digestibility of some feeds.

(See FILARIASIS.)

Filariasis is a group of diseases caused by the presence in the body of certain small thread-like nematode worms, called filariae, which are often found in the bloodstream. Biting insects act as vectors. (See HEARTWORM and TRACHEAL WORMS for canine filariasis; also EQUINE FILARIASIS; BRAIN DISEASES.) Infection is generally not considered a ZOONOSIS, although a case of conjunctivitis has been reported.

Parafilaria bovicola causes bovine filariasis in Africa, the Far East, and parts of Europe. The female worm penetrates the skin, causing subcutaneous haemorrhagic lesions that resemble bruising. Eggs are laid in the blood there. Downgrading of carcases at meat inspection is a cause of significant loss. MACROCYCLIC LACTONES (DORAMECTIN, IVERMECTIN, MOXIDECTIN) by injection are useful for control.

(See MONKEYS, DISEASES OF.)

These are minute filaments with specific antigenic properties attached to the surface of bacteria. They can be used in vaccines against E. coli, for example. (See also under GENETIC ENGINEERING.)

A technique in which a fine hypodermic needle is used to aspirate a tissue sample for cytological examination. (See CYTOLOGY; LABORATORY TESTS; PARACENTESIS.)

Finnish Landrace sheep are remarkable for high prolificacy, triplets being common, and four or five lambs not rare.

Not a common dog in Britain but is seen at shows. Progressive retinal atrophy may develop as a recessive trait.

(See FELINE INFECTIOUS PERITONITIS.)

A member of the phenylpyrazole family of non-systemic insecticides/acaricides applied topically for the treatment and prevention of flea and tick infestation in cats and dogs. It acts by blocking the invertebrate neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid, causing uncontrolled activity of the nervous system and death. In cats, one application is active for up to five weeks against fleas and for one month against ticks. In dogs, it is active for two months against fleas and for one month against ticks. It is not recommended for use on cats under 12 weeks or dogs under 10 weeks old, nor for animals suckling young. In view of the risk of animals becoming infected with tick-borne diseases abroad (see CANINE BABESIOSIS), it may be beneficial to treat them with such long-acting products before travelling. Fipronil is toxic to rabbits, GALLINACEOUS BIRDS and fish.

These are required in commercial kennels under the terms of the Animal Boarding Establishment Act 1963.

Fire is used as a management tool when working with heather and moorland. It also removes non-flying ARTHROPODS such as TICKS and thereby the diseases that they carry. Many fires are accidental or malicious and can result in deaths of animals, BURNS or SMOKE INHALATION. Fires involving animals, particularly farm animals, are included in the WELFARE CODES FOR ANIMALS.

Animals can react adversely to fireworks. All types should be kept away from them. Farm animals and horses should be in field far from bonfires or activity. If used to housing, it is probably best to house them and also try and cover windows etc. Similarly, placing pet or caged animals in a quiet place and away from the noise and flashes is helpful. Staying with pets and horses can be helpful provided the attendant is calm. Sedatives can be used but it is better to try and familiarise the pet by means of specific CDs which allow the animals to slowly become accustomed to loud noises. (See also THUNDERSTORMS.)

An old-fashioned treatment of thermocautery for locomotory injuries, used mainly in horses and sometimes dogs. It is a form of counter-irritation undertaken with a red hot iron under local anaesthesia, and usually involving the lower limb. It is mainly used in ligament injuries, and is thought to aid healing by resulting in enforced rest from the pain produced. There are doubts about its efficacy and the RCVS proposed a ban in the 1990s. However it was accepted that a veterinary surgeon must justify the need to fire based on the failure or absence of an alternative treatment. It is used commonly in some parts of the world but is not listed in the MUTILATIONS (PERMITTED PROCEDURES) REGULATIONS.

Bar firing involves burning the skin over the and around an area of tendon strain; pin firing involves localised burning directly into an affected tendon or other inflammatory lesion such as a CURB or a bony EXOSTOSIS.

A non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug used as a painkiller in canine osteoarthritis and to control inflammatory responses and post operative pain; it is also licensed for horses. It acts by inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis.

(See FOAL IMMUNODEFICIENCY SYNDROME.)

These are covered by the Diseases of Fish Act, and all are NOTIFIABLE in Britain: furunculosis and columnaris (bacterial); infectious pancreatic necrosis, viral haemorrhagic septicaemia, infectious haematopoietic necrosis and spring viraemia (viral); whirling disease (protozoan); ulcerative dermal necrosis and erythrodermatitis (of unknown cause).

Yersinia ruckeri infection causes the death of trout and is called ENTERIC REDMOUTH DISEASE. The fish become lethargic, dark and swim near the surface and show exophthalmos and small haemorrhages particularly on the pectoral fin. It appears to affect the heart.

On a fish-farm in England, 4,900 rainbow trout died from CEROIDOSIS over a four-month period. Affected fish swam on their sides or upside down, and often rapidly in circles. A few were seen with their heads out of water, swimming like porpoises.

Aquarium fish may be affected with fish tuberculosis, caused by Mycobacterium piscium, M. platypoecilus, or M. fortuitum. These cause a granulomatous condition which can prove fatal. Skin infection may develop in people handling diseased fish. (See also PETS, CHILDREN’S AND EXOTIC; WHIRLING DISEASE; SPRING VIRAEMIA OF CARP.)

This may occur through liquor from silage clamps seeping into streams, etc. The following, in very small concentrations, are lethal to fish: DDT, Derris, BHC (Gammexane), Aldrin. Many agricultural sprays may kill fish, as will snail-killers used in fluke control. In one case, many thousands of trout died. The owner of the trout farm reported that they had been leaping out of the water on to the banks. The Devon VI Centre’s findings suggested that the inadvertent contamination by excessively chlorinated water, into the stream supplying the trout farm, was to blame. In Hampshire the flushing of drains with a chlorine preparation led to similar trouble in river trout. The autopsy findings were ‘scalding of the flanks, fins, and gills’. (See also AFLATOXINS.)

Mortality among young salmon in cages was found to be caused by heavy colonisation of gills by Trichophyra species protozoa.

Toxins from CYANOBACTERIA in plankton can cause a high fish mortality; though clams, oysters, scallops, and mussels can absorb the alkaloids without harm.

In people, paralytic shellfish poisoning can occur within 30 minutes; deaths from respiratory paralysis within 24 hours have been recorded.

Fish-farming is a rapidly expanding industry, especially (in the UK) in Western Scotland. Rainbow trout and Atlantic salmon are the main species farmed. As the salmon cages are floated in sea lochs, the fishes come into close contact with wild fish attracted by the feed which may pass out of the cage. Thus disease may be spread from the wild fish to the farmed, with results that can be devastating. Fish lice are the greatest problem; they literally eat the fish alive.

In mainland Europe, carp and eels are farmed. Tilapia is an African fish which is farmed in various countries; it can be farmed in the warm water effluent from power stations. Sea bream and turbot are also farmed. In the USA, channel catfish are farmed in the southern states. The world’s largest producer of farmed fish, however, is China, where more than 20 species are produced.

The FARM ANIMAL WELFARE COUNCIL issued a report on the welfare of farmed fish in 1996.

This very popular hobby mainly concentrates on tropical fish. Many of these are imported and may have travelled a considerable distance before arriving in the UK. The methods used for their capture in some countries may cause injury. The result of this and of subsequent mishandling may not be apparent until the fish are in the possession of the hobbyist. Deaths even then can still be due to the method of capture.

(See ARGULUS.)

Fish-meal is largely used for feeding pigs and poultry, although it is also added to the rations for dairy cows, calves and other farm livestock. It is composed of the dried and ground residue from fish, the edible portions of which are used for human consumption. The best variety is that made from ‘white’ fish – known in the trade as white fish-meal. When prepared with a large admixture of herring or mackerel offal it is liable to have a strong odour, which may taint the flesh of pigs and the eggs of hens receiving it.

Fish-meal is rich in digestible, undegradable protein, calcium, and phosphorus; it has smaller amounts of iodine and other elements useful to animals. It contains a variable amount of oil. It forms a useful means of maintaining the amount of protein in the ration for all breeding females and for young animals during their period of active growth. From 3 per cent to 10 per cent of the weight of food may consist of white fish-meal. When pigs are being fattened for bacon and ‘fattening-off’ rations are fed, the amount of fish-meal is reduced; during the last four to six weeks it is customary to discontinue it entirely.

Many investigations have emphasised the very great economic value of fish-meal for animals fed largely upon cereal by-products. It serves to correct the protein and mineral deficiencies of these and thus enable a balanced ration to be fed. It serves a very useful purpose by enabling more home-grown cereals to be fed and largely replaces protein-rich imported vegetable products. (See also AMINO ACIDS; DIET AND DIETETICS.)