(See UPPER ALIMENTARY SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA.)

(See MAMMARY GLAND.)

(See UNIVERSITIES FEDERATION FOR ANIMAL WELFARE.)

‘Bulging eye disease’– an oculovascular myiasis of domestic animals in South Africa.

A break on the surface of the skin, or of any mucous membrane of a cavity of the body, which does not tend to heal. The process by which an ulcer spreads, which involves necrosis (death) of minute portions of the healthy tissues around its edges, is known as ulceration. Most ulcers are suppurative; bacteria prevent healing and often extend the lesion.

An ulcer consists of a ‘floor’ or surface which, in consequence of the loss or destruction of tissue, is usually depressed below the level of the surrounding healthy structures; and an ‘edge’ around it where the healthy tissues end.

Callous ulcer is a type of chronic ulcer often encountered in horses and dogs, when there is any pressure or irritation that interferes with the blood supply but does not necessarily cause immediate destruction of the skin. In most cases it is covered by a hard, leathery piece of dead skin from under which escapes a purulent fluid. ‘Bedsores’ in all animals may be of this nature.

‘Rodent ulcer’ is a term reserved in human medicine for an ulcerating carcinoma of the skin, but it is often colloquially used by dog- and cat-owners for an EOSINOPHILIC GRANULOMA. Skin cancer occurs in domestic animals, and such malignant tumours may ulcerate.

Tubercular ulcers may occur in dogs’ and cats’ skin in the form of raised plaques which ulcerate.

Internal ulcers may occur in the mouth (See MOUTH, DISEASES OF), in the stomach (See GASTRIC ULCERS), in the bowels (See INTESTINES, DISEASES OF), and in other parts.

Glanders ulcers are typically encountered in the mucous membrane of the nostrils, and have a ‘punched-out’ appearance.

Lip-and-leg ulcers occur in sheep with ORF.

Causes Any condition that lowers the general vitality of the animal, such as old age, chronic disease, malnutrition and defective circulation, will act as a predisposing cause. Among direct causes may be bacteria gaining access to wounds; irritation from a badly fitting harness, pressure of bony prominences upon hard floors insufficiently provided with bedding, and application of too strong antiseptics to wounds.

Treatment In the smaller animals a vitamin supplement may be indicated. An antibiotic or one of the sulfa drugs may be used.

Local treatment aims at converting the ulcer into what virtually becomes an ordinary open wound. The surface is treated with some suitable antiseptic, such as cetrimide, gentian violet, dilute hydrogen peroxide, etc. If one or two days of such treatment does not result in a clean, bright-red, odourless wound, or where there are shreds of dead tissue adherent to the surface, it may be necessary to curette the surface so that the dead cells may be separated from the healthy ones below them.

Animal-owners should note that after the surface of the ulcer has been rendered as healthy as possible, use of strong antiseptics or (worse still) disinfectants should cease, as these retard healing by the destruction of surface tissues.

Corneal ulcers are referred to under EYE, DISEASES AND INJURIES OF - KERATITIS. (See also CRYOSURGERY.)

A disease of adult salmon which occurs when they enter fresh water on their way to spawning grounds. It was first reported in the British Isles in the 1960s. Grey lesions are seen above the eyes, on the snout and on the side of the opercula (gill coverings). If they do not heal, the lesions spread to the skin of the head, ulcerate, and become prone to infection by Saprolegnia fungus. The fungal infection may be treated with zinc-free malachite green. The cause is unknown.

Ulcerative lymphangitis, also called ulcerative cellulitis, is a contagious chronic disease of horses, cattle, and, rarely, sheep and goats. It is characterised by inflammation of the lymph vessels and a tendency towards ulceration of the skin over the parts affected.

Cause Corynebacterium bovis (pseudotuberculosis). It gains access through abrasions. Poor hygiene and lack of exercise are associated problems. Infection may be carried by grooming tools, harness, utensils, etc., from one horse to another.

Signs The commonest seat of the disease is the fetlock of a hind-leg. This part becomes swollen and slightly painful. Small abscesses appear; ulcers follow. The condition gradually spreads up the leg.

Treatment Antibiotics.

This has been reported in the UK, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and the USA. It may give rise to foot-rot in pigs, ulceration of the skin, and scirrhous cord.

A viral infection, which has to be differentiated from ORF, and is characterised by ulcers on the face, feet, legs, and external genitalia. It is seen in many parts of the world including Europe, America and Africa.

Ulcerative enteritis is seen in chickens between 4 and 7 weeks of age, and in quails, turkeys, partridges and grouse at any age. Birds are depressed, with watery droppings; mortality can be very high, reaching 70 to 100 per cent. The cause is a virus. (See also QUAIL DISEASE.)

A disease of young salmonids caused by Haemophilus piscium in Canada and North-Eastern United States. Symptomless adults are carriers.

This is the inner of the two bones of the fore-arm. The shaft has gradually reduced in size as the number of digits has decreased, so that while the ulna is a perfect bone in the dog and cat, in the horse its shaft has almost completely disappeared and the bone is only represented by the olecranon process which forms the ‘point of the elbow’. The shaft of the ulna is liable to become fractured from violence to the fore-limb, but the commonest seat of an ulnar fracture is the olecranon process. This occurs from a fall in which the fore-limbs slip out in front of the animal, and the weight of the body comes down suddenly on to the point of the elbow. (See FRACTURES.)

Address: Unit 6, Cambane Industrial Estate, Newry, County Down BT35 6QH. Telephone: 077 3994 8516.

Ultra-high-temperature treatment of milk (UHT) involves heating it to between 135° C and 149° C (275° F and 300° F) for a few seconds. Suggested in 1913, UHT is used to produce long-life milk, on sale in Britain from 1965 onwards. This process does not affect the calcium nor the casein, but destroys some vitamins and probably some serum proteins (immune globulins). Calves grow less well on it than on raw or pasteurised milk.

The use of sound waves to show internal organs of a body, including tendons. It can be used for diagnosis and pregnancy detection.

Sound at a frequency above 20,000 cycles per second. Propagated by applying an electric current to one side of a piezoelectric crystal, which deforms and produces a sound wave.

Ultrasound is generally defined as an auditory frequency beyond that perceived by the human ear. Most humans hear and emit sound in the frequency range 2 to 20 kHz, while in some animals ranges are much greater. Bats, dolphins, many rodents and some insects have ranges that extend as high as 120 kHz – well beyond the limit of human detection. Pigs and poultry can detect higher ultrasound frequencies and may be disturbed by the noise given off by, for example, certain electronic equipment and dripping nipple-drinkers. Female rabbits communicate with their litters in ultrasound.

Ultrasound, in the range of 1 million to 10 million hertz, is used in non-invasive diagnostic imaging of internal body structures. It is widely used in pregnancy diagnosis of animals. (See also PREGNANCY DIAGNOSIS.)

In human medicine, ultrasound has been shown to be beneficial for wound healing, both in the treatment of pressure sores and in the preparation of trophic ulcers for skin grafting. Studies have shown that it influences the activity of fibroblasts.

When applied to chicken eggs for one to two hours per day during incubation, ultra-violet light increases the embryonic development and hatching weights. Longer periods are deleterious.

Ultra-violet rays are used in the treatment of various skin diseases, etc., and in the diagnosis of ringworm and porphyria; also in the fluorescent-antibody test for various infections including rabies.

Ultra-violet rays and eye cancer Research has shown that ultra-violet radiation may be of primary importance in triggering cancer.

A source of ultra-violet light is important in the husbandry of tropical and equatorial species kept in captivity, especially reptiles (See IGUANA). Lack of ultra-violet light can lead to metabolic disorders in these animals due to a deficiency of VITAMIN D.

(See under PARTURITION.)

The protrusion of abdominal contents through an opening in the abdominal wall at the umbilicus. The protruding material is covered by the skin and subcutaneous tissues. What protrudes depends on the extent of the opening. It may be just omental fat, or can include intestines. Usually the protrusion can be reduced by manipulation. However, if it is irreducible it may become strangulated, resulting in signs of pain and distress. Some are due to trauma or a weakened wall around the umbilicus. However some hernias in cattle and dogs can be inherited. Dog breeds involved include AMERICAN COCKER SPANIELS and BULL TERRIERS. (See also HERNIA - UMBILICAL HERNIA.)

Umbilicus is another name for the navel.

Elephants seek out and gorge themselves on the fruits of this tree, leading to sexual excitement. Ostriches may behave similarly.

Infection with Uncinaria stenocephala, one of the hookworms of the dog.

(See under COMA; FITS; SYNCOPE; EPILEPSY; NARCOLEPSY.)

A fungicide, used in the treatment of ringworm, etc.

Used to describe the jaw, where there is front tooth malocclusion with a shortened maxilla (upper jaw) and protruding mandible (lower jaw). It is seen in all species and in certain dog breeds including BOSTON TERRIERS. (See PROGNATHISM.)

Undulant fever in Man is caused by Brucella melitensis, B. abortus suis, or B. abortus. The latter organism is responsible for ‘contagious abortion’ (brucellosis) of cattle, and it is probable that most cases of undulant fever in man caused by B. abortus arise through handling infected cows or from drinking their milk. Infection can readily occur through the skin. Numerous cases have occurred in veterinarians, following mishaps with Strain 19 vaccine, e.g. accidental spraying into the eyes or injection into the hand. In America, B. abortus suis is an important cause of undulant fever in man; B. canis likewise.

Signs are vague and simulate those of influenza except that undulant fever lasts for a much longer time, even many months. Temperature is generally raised but fluctuates greatly; there are muscle pains, headache, tiredness and inability to concentrate. One or more joints may swell. There may be constipation. The organisms are present in the bloodstream and in the spleen.

The disease is serious, not so much because of its mortality (1 to 2 per cent), but because of incapacity occasioned by its long duration. (See BRUCELLOSIS and CHEESE.)

Prevention Anyone handling aborting cows, or their fetal membranes, or even calving an apparently normal cow, should wear protective gloves or sleeves (which nevertheless sometimes tear), and wash arms and hands in a disinfectant solution afterwards. Avoid drinking any cold milk that has not been pasteurised.

Occurring on one side of the midline of the body but not the other.

Address: The Old School, Brewhouse Hill, Wheathampstead, Hertfordshire AL4 8AN. Telephone: 01582 831818; email: ufaw@ufaw.org.uk; website: www.ufaw.org.uk.

The term is used in law to describe whether or not a person has been guilty of causing this to an animal. It is probable that all animals will suffer at times from disease, illness of other problems of a physical nature. However it is when the suffering could be alleviated or avoided and this suffering may be deliberate or not, but includes neglect again intentional or unintentional. (See ANIMAL WELFARE ACT 2006; FARM ANIMAL WELFARE COMMITTEE; ‘FIVE FREEDOMS’ FOR FARM ANIMALS; SUFFERING; WELFARE OF FARMED ANIMAL REGULATIONS 2007.)

A survey of just over 40 per cent of 1,380 animal welfare organisations contacted in a 2010 survey took in 89,571 dogs and 156,826 cats. Three quarters of all dogs and 77.1 per cent of cats were re-homed, and 10.4 per cent of dogs and 13.2 per cent of cats were euthanased. (See STRAY DOGS AND CATS.)

Also known as ‘RAW’ MILK or ‘GREEN TOP’ MILK. In England, Wales, and Northern Ireland it is legal to sell such milk without PASTEURISATION directly to customers provided it is clearly labelled. Such milk is also available and is used in milk products such as cheese, cream in many countries, and unpasteurised cheeses can be sold in UK shops. It has been illegal to sell such milk in Scotland since 1983, following an outbreak of LISTERIOSIS. Those producing and selling such milk need stringent regard to cleanliness and are TUBERCULIN TESTED annually. Some consumers are able to distinguish pasteurised milk from that unpasteurised, and the latter does have higher levels of some B vitamins and FOLATES. The reasons for pasteurisation are those of infections, some of which may be carried in the cow’s udder in the UK or elsewhere. They include BOVINE TUBERCULOSIS, BRUCELLOSIS, CAMPYLOBACTER INFECTIONS, LISTERIOSIS and SALMONELLOSIS. There were been no recorded disease outbreaks in England and Wales from unpasteurised milk since 2002.

(See under LIPIDS; VITAMINS - VITAMIN E.)

(See under INJECTIONS.)

A number of different conditions involving activation of warts in older suckler cattle by prolonged (over many years) ingestion of bracken, which contains activating factors. The lesions can occur in the mouth, oesophagus and reticulorumen and the signs vary according to the tumour site. There is no treatment but prevention is by improving the nutrition provided to the cattle.

This starts at the NOSE AND NASAL PASSAGES, passes through the PHARYNX, LARYNX, TRACHEA and ends in the BRONCHI. (See also LOWER RESPIRATORY SYSTEM.)

A PYRIMIDINE base found in DNA and RNA.

(adjective, Uraemic)

Uraemia results when the waste materials that should be excreted into the urine are retained in the body, through some disease of the kidneys, and are circulated in the bloodstream. Blood urea is in excess. Death may be preceded by convulsions and unconsciousness. In the slower types there is usually a strong urinous odour from all the body secretions. In acute cases the administration of glucose saline subcutaneously may help; likewise, withdrawal of a quantity of blood (provided that saline is given). (See URINE - ABNORMAL CONSTITUENTS OF URINE; LEPTOSPIROSIS; KIDNEYS, DISEASES OF.)

A congenital cleft palate.

(See URIC ACID.)

Urea (carbamide) is a crystalline substance of the chemical formula CO(NH2)2, which is very soluble in water and alcohol. It is the chief waste product discharged from the body in the urine, being formed in the liver and carried by the blood to the kidneys. The amount excreted varies with the nature and the amount of the food taken, being greater in the carnivora, and when large amounts of protein are present in the food. It is also increased in quantity during the course of fevers. Urea is rapidly changed into ammonium carbonate after excretion and when in contact with the air, owing to the action of certain micro-organisms.

Determination of the blood urea level is an important aid to the diagnosis of kidney failure.

Some of the micro-organisms which inhabit the rumen can synthesise protein from urea. It was accordingly suggested that urea might be substituted for protein in concentrates fed to cattle. This has been called the protein-sparing effect of urea, which is a non-protein source of nitrogen.

The emphasis has now shifted more to the value of urea in increasing the intake and aiding the digestion of low-quality roughages, and it has been widely used as a dietary supplement for cattle and sheep on poor pasture in many parts of the world. Where extra energy, in the form of readily digestible carbohydrate, is provided in addition to the urea, both roughage digestibility and feed intake improve. In these circumstances the urea stimulates multiplication of cellulose-digesting organisms, so that the urea-fed animal may be able to make more effective use of roughage than the one receiving no urea.

In the ruminant animal, any injudicious feeding of urea can give rise to poisoning by ammonia, since it is this which is released in the rumen and then converted into microbial protein. Excess ammonia can cause the animal’s death. It is essential, therefore, that urea is taken in small quantities over a period, and not fed a large amount at a time.

Urea is often added to molasses and fed via ball feeders which prevent rapid and excessive uptake of the liquid and ensure maximum utilisation of urea. Under optimum farm conditions only 15 to 30 per cent of the dietary protein can be replaced by urea. As a rule of thumb, urea, if incorporated uniformly within the dairy ration, has been shown to be safe at a level of 1 per cent. Combined with 5 per cent barley, that mix can replace 5 per cent ground-nut meal in the ration. In the diets of finishing beef cattle, the animals can gradually have the proportion of urea increased.

Mixing starch with urea at high temperatures and pressure results in the starch become gelatinised and forming a homogeneous mass. In the rumen this material decomposes slowly, gradually releasing urea and carbohydrates. This allows better utilisation of urea.

Some guidelines for urea feeding

1. Introduce urea feeding gradually, i.e. at a slowly increasing level over a period of three to four weeks, with adequate minerals and vitamins provided.

2. Avoid starting newly calved cows on it (but it may be included in the steaming-up ration), or giving it to calves under three months of age.

3. Ensure that urea is fed with adequate readily digestible carbohydrate, as is contained in cereals, molasses, sugar-beet pulp, maize silage, etc.

4. Do not exceed levels of urea recommended by the supplier.

5. Ensure that urea is fed little and often, and not irregularly or at long intervals.

Urea poisoning Signs include salivation, excitement, running and staggering, jerking of the eyeballs and scouring.

Acute urea poisoning killed 17 beef cows in a group of 29 in the south of Scotland. The animals died over an 8-hour period as a result of drinking water which had been carried to a trough in a tanker previously used for transporting urea fertiliser. It was calculated that as little as 10 litres of the water would have provided a fatal dose of urea to a 500 kg cow.

Formerly known as T-mycoplasmas, these have been isolated from the lungs, and also the urogenital tract of several species of animals. They are a likely cause of pneumonia (See CALF PNEUMONIA) and infertility (See VULVOVAGINITIS, GRANULAR.)

The ureter is the tube which carries the urine excreted by a kidney down to the urinary bladder. Each ureter begins at the pelvis (main cavity) of the corresponding kidney, passes backwards and downwards along the roof and walls of the pelvis, and finally ends by opening into the neck of the bladder. The wall of the ureter is composed of a fibrous coat on the outside, a muscular coat in the middle, and this is lined by a mucous membrane consisting of cubical epithelium.

The urethra is the tube which leads from the neck of the mammalian bladder to the outside, opening at the extremity of the penis in the male, and into the posterior part of the urogenital passage in the female. It serves to conduct the urine from the bladder to the outside; also the semen.

Owing to its extreme shortness in the female, the urethra is not subject to the same disease conditions as in the male, where the tube is considerably longer. In fact, disease of the urethra in the female hardly ever arises except as a complication of either disease of the bladder, on the one hand, or of the vagina on the other.

Urethritis Inflammation of the urethra is usually associated with CYSTITIS, and may be the result of an infection, or of some irritant poison (such as CANTHARIDES) present in the urine. The lining mucous membrane may also be inflamed by crystalline deposits. (See FELINE LOWER URINARY TRACT DISEASE; UROLITHIASIS; URETHRAL OBSTRUCTION.)

In most cases of urethritis there are signs of pain and distress whenever urine is passed or when the parts are handled. A little blood may be seen.

Stricture is an abrupt narrowing of the calibre of the tube at one or more places. In almost all cases of true stricture there has been some injury to the urethra or penis, resulting in the formation of scar tissue, which eventually contracts and decreases the lumen of the tube. A few cases, however, are caused by a rapidly-growing tumour.

Injuries to the urethra may follow a severe crush or blow which causes fracture of the pelvis or of the os penis in the dog, but this is rare. They are usually obvious when the injury has involved the surface of the body, and may be suspected if there is an inability to pass urine, or if the urine contains blood or pus following upon a severe injury to the hindquarters of the body. A complication of urethral injuries is abscess formation around the urethra and consequent stricture at a later period.

In sheep, the injudicious use of hormones to increase liveweight gain has killed lambs, apparently as the result of urethral obstruction. In male calves and lambs, crystalline deposits of magnesium ammonium phosphate can occur, resulting in ‘stones’ which cause urethral obstruction if the animals are receiving an unbalanced diet, especially one with a high level of magnesium in their concentrate feed.

Reducing the levels of magnesium supplementation can stop further cases of urolithiasis in intensively fattened male lambs offered a cereal-based diet ad lib. (See also under URINARY BLADDER, DISEASES OF - URINARY CALCULI.)

(The AFRC recommendation is not more than 1.4 g/kg dry matter.)

Obstruction of the male urethra is a common condition in cats, and fairly common in the dog. (See FELINE LOWER URINARY TRACT DISEASE.)

Unless relieved, urethral obstruction can lead to rupture of the bladder and death.

Perineal urethrostomy is a surgical operation for the treatment of urethral obstruction; it consists of making a permanent opening in the urethra, the lining mucous membrane and the skin being joined by sutures. (Urethrostomy differs in this respect from URETHROTOMY, in which the urethra is incised – to remove a wedged calculus, for example – but immediately closed.)

Urethrostomy is performed mainly in cats suffering from FELINE LOWER URINARY TRACT DISEASE. It is not in itself a cure for this, but rather for the often-associated urethral obstruction. The operation is an alternative to euthanasia when the cat cannot be catheterised, or has already been subjected to this on two or more occasions, when repetition could be regarded as inhumane.

Urethrostomy, skilfully performed, can be successful, in both the short and the long term.

Complications can arise, however, after both urethrotomies and urethrostomies, and include: leakage of urine into surrounding tissues; haemorrhage; and stricture, as the result of scar formation. Should the latter occur, it leaves the cat in the same state as it was before the operation, so that nothing has been gained.

Urethrostomy makes the male cat anatomically similar to the female, so that ascending infections may occur.

An operation to gain access to the lumen of the urethra, usually to remove the cause of the obstruction. The opening is closed once the cause has been removed.

Uric acid is a crystalline substance, very slightly soluble in water, white in the pure state, and found in the urine of flesh-eating animals in normal conditions. It is the end product of PURINE metabolism or oxidation in most species except primates, man and DALMATIAN DOGS. Other animals use uricase to convert the relatively insoluble uric acid to very soluble allantoin. It is also found in some kidney stones and urinary calculi, and may be present in joints affected with GOUT.

Urinary antiseptics include hexylresorcinol, mandelic acid, hexamine (for acid urine; not effective in alkaline urine) and buchu. Their use is now rare.

The reservoir for urinary waste products in mammals and CHELONIA. In some mammals the bladder is situated in the pelvis, but in the dog and cat it is placed further forward in the abdomen, while in the pig and cattle it may be almost entirely abdominal when distended. The size of the organ varies with the breed and sex of the animal, and its capacity depends upon the individual. Two small tubes – called URETERS – lead into the bladder, one from each kidney, and the larger, thicker URETHRA conveys urine from it to the exterior. The constricted portion from which the urethra takes origin is called the neck of the bladder, and is guarded by a ring of muscular tissue – the SPHINCTER.

Structure The wall of the bladder is somewhat similar to that of the intestine, and consists of a mucous lining on the inside, possessing flat, pavement-like epithelial cells; a loose submucous layer of fibrous tissue very rich in blood vessels; a strong, complicated muscular coat in which the fibres are arranged in many directions; and on the surface an incomplete peritoneal coat covering the organ. In places this peritoneal covering is folded across to parts of the abdominal or pelvic wall in the form of ligaments which retain the bladder in its position.

In young animals the bladder is elongated and narrow, and reaches much further forward than it does in the adult. In the unborn fetus its forward extremity communicates with the outside of the body until just before birth, when the passage becomes closed at the umbilicus, or navel, and the bladder shrinks backwards.

Cystitis Inflammation of the bladder is often infective in origin, with micro-organisms coming either from the KIDNEYS via the URETERS, or, in the female, in the reverse direction – i.e. via the URETHRA from an infected vagina.

Leptospirosis is a common cause of NEPHRITIS and cystitis in farm animals and in dogs. E. coli is another common pathogen in dogs; and Corynebacterium suis in pigs.

In dogs, cystitis is very occasionally found to be due to the bladder worm Capillaria plica; and in cats to C. feliscati. The parasites’ eggs may be found in the urinary sediment. Anthelmintics may be used for treatment.

Inflammation of the bladder may be caused by the abrasive action of a sand-like crystalline deposit as in the FELINE LOWER URINARY TRACT DISEASE (FLUTD) or, to a lesser extent, by sizeable urinary calculi.

Signs In acute cystitis, small quantities of urine may be passed frequently, with signs of pain and/or straining on each occasion. Blood may be seen in the urine. The larger animals may walk with their hind legs slightly abducted, and the back is often arched in all animals.

Treatment This will naturally vary according to the cause. Therefore, analysis of urine from affected cases is usually required. An appropriate antibiotic may be used to overcome infection. Modifying urine pH is rarely done these days. If it is, urine acidifiers, such as ascorbic acid or ammonium chloride, or alkalisers, such as potassium citrate or sodium bicarbonate, may be used. Pain-relievers may be needed. Supportive therapy is also required (e.g. dietary changes to encourage alterations in the chemical composition of the urine and adequate fluid access to encourage dilution.)

Urinary calculi These, associated with high grain rations and the use of oestrogen, produce heavy losses among fattening cattle and sheep in the feed-lots of the USA and Canada. However, this condition does not seem to present the same problem in the barley beef units in this country, although outbreaks do occur in sheep fed high grain rations. The inclusion of 4 per cent NaCl in the diet has been shown to decrease the incidence of urinary calculi blockage.

In male calves and lambs, crystalline deposits of magnesium ammonium phosphate (STRUVITE) cause urethral obstruction if the animals are receiving too high a level of magnesium or phosphorus supplement in their concentrate feed. (See URETHRAL OBSTRUCTION.)

Urinary calculi may occur in an individual animal irrespective of its diet, or of hormone implants. There may be one large calculus present in the bladder, or several small ones, or the crystalline sand-like deposit already mentioned. In such cases, although hyaluronidase might be tried, treatment usually has to be surgical, i.e. cystotomy.

Rupture of the bladder This condition is usually quickly fatal, and is brought about by a painful over-distension of the bladder due to urethral obstruction. The condition may be seen in foals, mainly colts, at parturition. Diagnosis is based on clinical findings together with ultrasonography. Prompt surgery is usually successful.

Tumours These may cause difficulty in passing urine, and sometimes the presence of blood in the urine.

In a study of 70 cases in the dog, no urinary signs were found in nine. In the other 61, signs included haematuria, dysuria, tenesmus, incontinence, and polyuria. Sixty-two dogs had primary tumours; 44 of these were carcinomas. Several papillomas were found during cystotomy for urinary calculi.

A squamous cell carcinoma occurs in the bladder of older suckler cows following ingestion of bracken over many years. The main sign is blood in the urine with frequent MICTURITION and, often, a loss of condition.

This is a naturally occurring extracellular matrix obtained from specially bred pigs that promotes remodelling of damaged and injured tissue. It is used as a dehydrated membrane or hydrated membranes or an injection of powdered material. It recruits cells for tissue differentiation from the circulatory and local tissues. It has been used in the USA for the treatment of tendon injuries when other treatments have failed.

(See above, and under CALCULI - URINARY CALCULI; URINARY BLADDER, DISEASES OF.)

(See INCONTINENCE.)

(See KIDNEYS; URETER; URINARY BLADDER; URETHRA.)

The act of passing urine. (Synonym: MICTURITION)

A brief outline of the formation of urine is given under KIDNEYS - FUNCTION. (See also HOMEOSTASIS.)

Not only are waste products removed from the bloodstream by the kidneys, but most poisons taken into the body are eliminated from the system by way of the urine; thus, quinine, morphine, chloroform, carbolic acid, iodides and strychnine can be recognised in the urine by means of appropriate tests, while there is abundant evidence to show that during bacterial diseases, the kidneys eliminate toxins.

Specific gravity The specific gravity of the urine of animals varies between wide limits; for average purposes the following figures are given:

|

Lowest |

Average |

Highest |

Horse |

1014 |

1036 |

1050 |

Cow |

1006 |

1020 |

1030 |

Sheep |

1006 |

1010 |

1015 |

Pig |

1003 |

1015 |

1025 |

Dog and cat |

1016 |

— |

1060 |

Reaction The urine of the herbivorous animals is usually alkaline, and that of the flesh-eating animals, acid. The alkalinity in herbivores is due to the salts of the organic acids that are taken in with the vegetable diet, such as malic, citric, tartaric and succinic; these acids are converted into carbonates in the body, and these latter are excreted in solution. In the case of some foods, such as hay and oats, an acid urine may be produced when they are fed to the horse. In the carnivorous animals the acidity is due to sodium acid phosphate. The pig’s urine may be acid or alkaline according to the nature of its food.

Amount The quantities of urine excreted depend upon many factors, among which may be noted: season, diet, amount of water consumed, condition of the animal, secretion of milk, pregnancy, age, and size of the animal. (See also PREGNANCY DIAGNOSIS.)

The following are average figures of the amounts excreted during 24 hours:

Horse: 3 litres to 11 litres (5 pints to 20 pints), average 5 litres (9 pints)

Cow: 5.7 litres to 22 litres (10 pints to 40 pints), average 12.5 litres (22 pints)

Sheep: 285 ml to 855 ml (0.5 pints to 1.5 pints), average 570 ml (1 pint)

Pig: 1.4 litres to 8 litres (2.5 pints to 14 pints), average 4.5 litres (8 pints)

Dog: 440 ml to 995 ml (0.75 pints to 1.75 pints), average 680 ml (1.25 pints)

Abnormal constituents of urine Albumin may be excreted when there is some disease of the kidneys. Sugar is found in DIABETES MELLITUS and it is also found in smaller amounts after an animal has been fed on a diet that is too rich in sugar. In this latter case – known as glycosuria – the sugar disappears when the feeding is corrected. Pus and tube-casts are the signs of inflammation or ulceration in some part of the urinary system. Bile in the urine is a sign that there is some obstruction to the outflow of bile into the intestines, and that the bile is being reabsorbed into the bloodstream and excreted by the kidneys.

Urine samples offer a useful source of information about the health status of the URINARY ORGANS of animals and also of certain other organs, and their metabolic status. The tests used vary with the species. The tests may be simple biochemical analyses using proprietary ‘dipstick’ tests to detect protein, sugar, biliary products, blood, haemoglobin, and nitrates. The use of sulphosalicylic acid to detect the presence and quantity of protein, microscopy of any sediment to observe cells, (including blood as well as cells from the urinary tract itself), casts from the kidney tubules. On rare occasions in mammals (but frequently in reptiles and birds, sometimes due to the presence of intestinal waste products) parasites may be seen. Bacteriology can also be performed. In ruminants tests for pH, ketone bodies including BOHB, MAGNESIUM, etc. are used.

Urine-drinking, or licking, by cattle may be a sign of sodium deficiency. (See ‘LICKING SYNDROME’.)

(See UROVAGINA.)

Loss of hair and inflammation of the skin caused by persistent wetting with urine. It is a common problem in obese rabbits or those fed a diet with excessive amounts of concentrates.

This is the normal method used by the male cat to mark out its territory. Under natural conditions this may be some 2 km2 (5 acres) or so in extent. The territory-marking serves as a warning to other males to keep out and, perhaps, also as an invitation to females in oestrus to enter.

Urine-spraying is not confined to the entire male, but may also be indulged in by the entire female, and even by neuters of either sex. It may also be an expression of sexual excitement.

Spraying indoors is often the result of the invasion of a cat’s territory by an intruder such as a new person (if the owner takes on a new partner, for example), the arrival of a baby or another pet. The appearance of a cat at the window of a house or in the garden may trigger spraying. Another cause is the installation of a cat flap, if the flap does not keep other cats out of the house. A move to a new home, or even the rearrangement of furniture, may initiate urine-spraying indoors. Spraying is common in households where several cats are kept.

Hormonal drugs such as progestins, which block the effects of male hormones, can be used to prevent spraying in male cats. Tranquillisers may be of benefit in more intractable cases. If a particular area is targeted, the cat’s food bowl can be placed there, as cats will not spray close to where they eat. Feline pheromone, in an aerosol, is said to inhibit the cat’s desire to spray. α-casozepine (Zyllere), a milk protein used in the management of stress-related problems may be effective. (See BEHAVIOUR PROBLEMS.)

An instrument designed for the estimation of the specific gravity of urine.

Resulting to the urinary and genital systems.

A small projection at the urogenital opening of fish. Damage or infection at this area can lead to problems in shedding eggs or semen (‘milt’).

The formation of calculi (stones), or of a crystalline sand-like deposit, in the urinary system. A bacterial or viral infection may precede or follow the condition. Certain proteins and peptides are associated with the human condition and it appears to be the same for dogs although these proteins and peptides have not been identified. (See URETHRAL OBSTRUCTION; URINARY BLADDER, DISEASES OF; FELINE LOWER URINARY TRACT DISEASE; and URETHRA, DISEASES OF.)

The mineral composition of 2700 of these were studied, after their removal from dogs. Their composition was STRUVITE in nearly 60 per cent of those tested followed by calcium oxalate (31per cent). They were detected more frequently in males (52.4 per cent). In horses the most common mineral was calcium carbonate.

An oil-secreting bi-lobed gland, situated on the PYGOSTYLE of birds. It is also called the PREEN GLAND. This gland contributes a small amount of lipid to the skin of birds, the majority being contributed by the epidermal cells. (See SKIN.)

(See HEXAMINE.)

Also known as URINE POOLING or VESICOVAGINAL REFLUX. There is urine accumulation in the vaginal fornix, and the long-term often interferes with breeding in mares because of VAGINITIS, CERVICITIS and ENDOMETRITIS. Diagnosis can only be made with a VAGINOSCOPE, best done during OESTRUS, but may be difficult to confirm, as some mares intermittently pool urine. Usually treatment is surgical.

Urticaria (nettle rash) is a disease of the skin in which small areas of the surface become raised in weals of varying sizes. It occurs in horses, cattle (when it is often called ‘blaines’ or ‘hives’), pigs and dogs.

Causes The condition is not necessarily specific. It may follow exposure to the leaves of the stinging nettle (hence one of its names); insect bites may produce it; and it may be associated with diet. It may occur in certain specific conditions in the horse, such as PURPURA HAEMORRHAGICA, DOURINE, INFLUENZA, etc. Urticaria is usually, if not always, of an allergic nature.

Factitious urticaria, where weals are formed following rubbing or scratching, should be called DERMATOGRAPHISM and is uncommon in the dog and other species.

Signs As a rule there is little to be seen beyond the local swellings of the skin. These may vary in size from a pea to a walnut, and are generally more or less almond-shaped. They are painless to the touch, show no oozing discharge, are scattered irregularly over the whole body, and sometimes involve the skin of the eyelids, nostrils and perineum. In cattle especially they may attain a great size in the throat region and produce difficulty in breathing.

Treatment Consists of the use of ANTIHISTAMINES, a light diet, and calamine lotion. An antibiotic may be used to prevent infection from occurring.

Usutu virus is a FLAVIVIRUS closely related to WEST NILE VIRUS. An outbreak in Vienna in 2000 is thought to have been carried by swallows migrating from Africa and resulted in many blackbirds around the city dying. Blue tits and sparrows can be infected. The disease is transmitted by mosquitoes, In humans, the signs are fever and a rash, but serious illness has not been reported. Humans and primates are terminal hosts for the virus and so are not a source of infection for other animals. Between 2005 and 2011, examination of British wild birds has not identified its presence.

Relating to, or pertaining to the UTERUS.

These are discussed under UTERUS, DISEASES OF and INFERTILITY. A list of the principal organisms which infect the uterus in the various species is given under ABORTION; but for the mare, see EQUINE GENITAL INFECTIONS IN THE MARE.

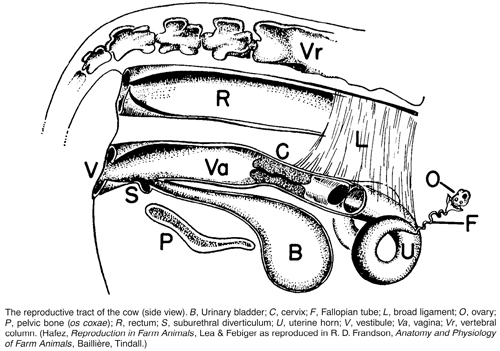

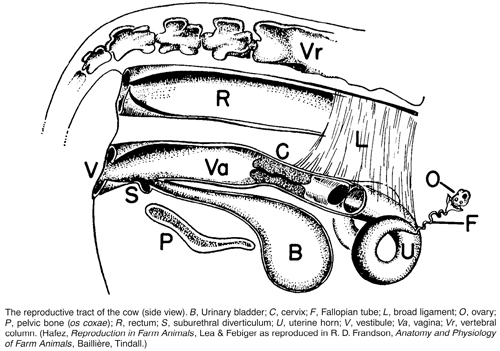

The uterus is a Y-shaped organ consisting of a body and two horns, or cornua; it is lined by an elaborate mucous membrane which presents special features in different species of animals. The uterus lies in the abdomen below the rectum and at a higher level than the bladder. It becomes continuous with the vagina posteriorly. Its most posterior portion, known as the cervix, usually lies partly in the pelvis. From the tip of each horn to the ovary on the corresponding side runs the Fallopian tube or oviduct, which conducts the ova from the ovary into the uterus.

In the human female the body is large and horns, for practical purposes, do not exist. In rabbits the two horns open into the vagina separately. The uteri of domesticated animals are intermediate between these types.

The walls consist of three coats: a peritoneal covering on the outside continuous with the rest of the peritoneum; a thick muscular wall arranged in two layers, the fibres on the outside being longitudinal and those on the inside circular; an innermost coat, which is mucous membrane. This latter is very important, since it is by its agency that the ovum and the sperms are nourished before they fuse; it is through the mucous membrane that nutrients and oxygen are conveyed from dam to fetus, and that much of the waste products leave the fetal circulation to pass into the maternal bloodstream. It consists of epithelial cells, amongst which lie the uterine glands which secrete the so-called ‘uterine milk’ serving to nourish the newly fertilised ovum.

The most posterior extremity of the uterus is called the os uteri, and this forms the opening into the cervix uteri, which is a thick-walled canal guarding entrance into the cavity of the body of the uterus. Normally this is almost or completely shut, but during oestrus it slackens, and during parturition it becomes fully opened to allow exit of the fetus. The uterus is held in position by means of a fold of peritoneum attached to the roof of the abdomen, which carries blood vessels, nerves, etc. This is known as the ‘broad ligament’; it is capable of a considerable amount of stretching.

(See PREGNANCY AND GESTATION; PARTURITION.)

The mare The shape of the uterus of the mare most nearly approaches that of the human being. It possesses a large body and comparably small horns. During pregnancy the fetus generally lies in horn and body. The mucous membrane is corrugated into folds.

The cow The body is less in size than the horns, which are long, tapering, and curved downwards, outwards, backwards, and upwards to end within the pelvis at about the level of the cervix. The fetus lies in the body and one horn in single pregnancy, and when twins are present each usually occupies one horn and a part of the body. The mucous membrane presents upon its inner surface a large number (100 upwards) of mushroom-shaped projections – cotyledons. The fetal membranes are attached to the dome-like free surface of the cotyledons, in which are a large number of crypts, which receive projections called villi from the outer surface of the chorion.

The ewe has a uterus similar to that of the cow except that it is smaller and that the cotyledons are cup-shaped.

The sow has a small uterine body and a pair of long convoluted horns that resemble pieces of intestine. The mucous membrane is ridged but has no cotyledons. The young lie in the horns only.

The bitch and cat have uteri with comparatively short bodies and long, straight, divergent horns that run towards the kidneys of the corresponding sides.

The rabbit has a uterus with a short body and long straight horns. There is a double cervix and caudal to this, the urogenital sinus, a dilation of the cranial vagina.

(See PREGNANCY AND GESTATION; PARTURITION.)

Inflammation of the uterus (metritis) may be acute or chronic, localised (e.g. confined to the cervix), or involving more than one uterine tissue.

A list of uterine infections giving rise to infertility and abortion in the various species will be found under ABORTION, but for the mare, see under EQUINE GENITAL INFECTIONS IN THE MARE.

The mare

Acute Metritis This may occur either before or after foaling. When it takes place prior to the act it is usually associated with the death of the foal and its subsequent abortion, with or without discharge of the whole or a part of the membranes. In such cases the inflammatory condition may persist in an acute form and cause the death of the mare, or it may assume a chronic form after the abortion and render the mare incapable of further breeding; other cases are followed by recovery. Acute metritis occurring after normal foaling may arise through the conveyance of infection into the uterus by the arms or hands of the attendants, or by the ropes, instruments, or other appliances that are used to assist the birth of the foal; or it may be the direct result of retained membranes that undergo bacterial decomposition. (This may happen after most, but not all, of the fetal membranes have come away.)

Signs Acute metritis is a severe and often fatal condition. Within 24 to 48 hours, the mare becomes greatly distressed and loses all interest in the foal. She lies most of the time and refuses food; her temperature is usually high. Greyish blood-flecked discharge escapes from the vagina and soils the tail and hindquarters. The mare may become tucked up in her abdomen and stands with her back arched.

LAMINITIS may develop.

Prevention During foaling and after the act the greatest attention should be paid to the cleanliness of everything that is to come into contact with the genital tract of the mare. The attendant’s fingernails should be trimmed short, and the hands and arms should be well scrubbed with soap and water containing some antiseptic, such as Dettol. Finally the hand and arm should be lubricated with a suitable preparation marketed for this purpose. All appliances that are to be used should be boiled and kept in a pail of hot water when not actually in use.

One other factor is of the greatest importance: after a mare foals, the fetal membranes should be given attention. Normally they are discharged by means of a few comparatively mild labour pains within an hour of the birth of the foal. If, however, they are retained for longer than this period, the person in attendance should suspect that something may be wrong and seek veterinary advice.

In other cases, a series of violent pains may commence, when the bulk of the membranes are passed to the outside, where they hang suspended. Should this happen a sack or sheet should be placed under the dependent mass, and held so as to support the weight and relieve the tension on that portion that is still retained in the uterus. This is necessary lest the weight of the external membranes causes a tearing away from the non-separated part. Gentle traction should then be exerted upon the imprisoned portion; as a rule it will gradually detach itself and come to the outside. If no progress is made, veterinary assistance should be sought promptly.

Injections of PITUITRIN may obviate manual removal of the fetal membranes. A synthetic oestrogen may be preferred. (See HORMONE THERAPY.)

Regarding complete retention of the fetal membranes – when only a very small portion is seen hanging from the vagina – professional help should be obtained if there is no sign of any attempt at expulsion within 4 to 6 hours after foaling.

Generally speaking, membranes that have remained in position for 8 to 12 hours are starting to decompose, and decomposition means bacterial infection of the uterus (i.e. metritis) in almost every case.

Treatment The case must be considered most serious. The use of antibiotics or one of the sulfa drugs is indicated. (See also under NURSING OF SICK ANIMALS.) Any retained fetal membrane must be removed from the uterus using oxytocin injections. If unsuccessful, 5 litres of a sterile isotonic solution should be instilled through the cervix using a sterile catheter manufactured for the purpose. An oxytocin injection should be repeated after two hours if, again, unsuccessful. This should be repeated until the placenta is removed. The mare should be given NSAIDs as well as antibiotics. Further treatment and uterine irrigation should be repeated daily until the discharge is clean. When complications such as LAMINITIS or PNEUMONIA co-exist, they must receive separate attention.

Chronic Metritis This may originate as a sequel to an acute attack in some cases, but more commonly it is directly due to an injury or infection which is not sufficiently severe to produce an acute attack.

Signs There may be a general unthriftiness following foaling. The mare’s appetite is capricious, but her thirst is unimpaired. The temperature fluctuates a degree or two above normal. There may or may not be a dirty, sticky, grey, or pus-like discharge from the vagina, which causes irritation and frequent erections of the clitoris. The mare resents handling of the genital organs, but if the lips of the vulva are gently separated the mucous membrane is seen to be inflamed and swollen.

In other cases the pus collects in the cavity of the uterus and is retained there through closure of the os (see PYOMETRA). It sometimes happens that after the pus has collected for a certain period the os suddenly opens and 4.5 litres (1 gallon) or more of pus is discharged. The os then closes once more. Intervals between these evacuations may vary from a few days to three or four weeks. The mare’s general condition shows an improvement immediately following a sudden discharge of pus, but as it re-accumulates she relapses into her former chronic state. Chronic metritis may get gradually worse, and the mare dies. Cases taken in time usually recover with treatment, but further breeding is often impossible.

Treatment An early opportunity should be taken to evacuate the pus from the uterus, by douching and siphonage, or by irrigation as already described under ‘Acute metritis’.

Sulfa drugs or antibiotics may be used.

It should be emphasised that expert advice should be sought at the earliest opportunity.

(See also CONTAGIOUS EQUINE METRITIS.)

Torsion In the mare this tends to occur in the last third of pregnancy, but prior to foaling. It is a true torsion of the uterus and not of the anterior vagina, as in the cow. Diagnosis has to be carried out per rectum. There may be colic pains. Rolling the mare, like in the cow, is not an option. Correction should either be carried out standing with an arm through a small lower flank incision, with the mare needing sedation and a local anaesthetic block, or correcting through a mid-line ventral incision under a general anaesthetic.

The cow In the following brief account, much of what has been said in relation to the mare will apply to the cow as well, and only the main differences will be stated.

Acute Metritis In some cases where birth of the calf has taken place easily and naturally, metritis supervenes in the course of the first week or 10 days after calving, but in the majority of cases there has been some injury or infection at, or shortly after, parturition. Retention of the fetal membranes, which is so much more common in the cow than in other animals, is very often the contributory factor to an attack of acute metritis. The conveyance of infection by the hands and arms of the attendant, in his capacity of accoucheur, or insemination of a cow not in oestrus, are other causes.

Signs The cow generally becomes obviously affected between the second and eighth day after calving. The vulval lips swell and are painful when touched; the lining membrane of the vagina is intensely reddened and swollen. There are frequent and painful attempts at the passage of urine, the temperature rises to 41.5° C or 42° C (107° F or 108° F), the appetite is lost and there is a gritting of the teeth. Rumination is suppressed, the pulse is hard and fast, the milk secretion falls off or stops altogether. A discharge appears at the vulva.

Treatment Acute metritis in the cow should be looked upon as a contagious disease and precautions taken to prevent infection being conveyed to other cows that are soon due to calve. Actual treatment is similar to that as applied to the mare.

Chronic Metritis very often follows an acute attack in the cow. The animal partially recovers, the more acute signs subside, and there is apparently little or no pain. Milk yield may be reasonable, and the animal may appear bright. The general health, however, remains indifferent and there may be either a constant or an intermittent discharge from the vulva, which soils the tail and hindquarters, and has in many cases a putrid smell.

Chronic metritis may be due to Brucella abortus (see BRUCELLOSIS), Trichomonas fetus, Arcanobacterium (Actinomyces) pyogenes, or Campylobacter fetus, among other organisms. Another form of chronic metritis that attacks cattle is seen in virgin heifers that have never bred.

Pyometra (a collection of pus in the uterus) may result from infection introduced during natural service, insemination, or at or after calving. Treatment with CLOPROSTENOL may be helpful.

Treatment of chronic metritis in the cow is much the same as that in the mare, but see also under HORMONE THERAPY.

The ewe, sow and goat What has been said in respect to the larger animals applies to these animals to a great extent. It should be remembered that flesh from an animal that is suffering from a severe inflammatory condition, such as metritis, is not fit for human food. (See also SOWS’ MILK, ABSENCE OF.)

The bitch and cat In these carnivores, owing to the diffused placenta, and to the consequent sudden stripping bare of protective covering of a large surface, inflammation of the uterus is very prone to follow protracted or difficult parturition, especially when manual assistance from unskilled persons has been undertaken. As in other animals, an acute and a chronic form are recognised.

Acute Metritis may follow difficult whelpings, and retention of one or more fetal membranes. The membrane most commonly retained is that which belonged to the fetus that was born last and occupied the extremity of one of the horns of the uterus.

Signs The onset of inflammation of the uterus generally occurs within a week after whelping, but some cases are delayed a little longer than this, especially in cats. A rise in temperature, increased pulse and respiration rates, dullness, disinclination for movement, and an absence of appetite occur.

Cats and dogs seem to get ease from the pain by sitting crouched in an upright position on their hocks and elbows, and this posture is almost continually assumed. A discharge appears at the vulva. Vomiting may occur. The secretion of milk ceases and the puppies or kittens become clamorous for food. The sides of the abdomen are held tense and rigid, and any attempt at handling these parts is resisted. The animal may groan or grunt if the flanks are firmly pressed between the hands.

Treatment The use of antibiotics or sulfonamides is important. The uterus is syringed out with a non-irritant antiseptic such as dilute cetrimide solution; and pituitrin, ergometrine or dinoprost is given. Antiseptic pessaries may be introduced into the uterus. (See NURSING OF SICK ANIMALS; NORMAL SALINE; ANTIBIOTICS.) The puppies or kittens should be removed from their mother and may be reared either by hand of through the agency of a foster-mother.

Chronic Metritis is very common in the smaller animals, and is sometimes the sequel of an acute attack that has never completely cleared up. The cervix remains closed in most cases, so that the uterus becomes filled with pus (PYOMETRA) and the abdomen consequently enlarges. It is this increase in size that first draws attention to the condition, as a rule.

Treatment In cases of pyometra where some pus is coming away, a course of pituitrin injections may be useful (and it may be tried even where the cervix is closed). (See PITUITRIN) STILBOESTROL is no longer an alternative in EU countries. A two-way catheter may be used to wash out the pus. Penicillin or acriflavine may be used for irrigation of the uterus, and antibiotics or sulfonamides systemically. Ovario-hysterectomy is indicated in a number of cases but should not be postponed until toxaemia is far advanced or the animal too weak to stand the operation. Shock is severe.

Stricture of the cervix is one of the results of an inflammatory condition of this part. When inflammation has been severe, a certain amount of fibrous tissue is laid down around the canal, contracts and causes a narrowing of the passage.

Treatment is described under ‘RINGWOMB’ – a term used only for stricture in ewes, in which it is most often seen.

Tumours Benign tumours include lipoma, fibroma, papilloma, myoma and haemangioma (rare). Malignant tumours include lymphosarcoma, adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma.

Prolapse A partial or complete turning-inside-out of the organ, in which the inside comes to the outside through the lips of the vulva and hangs down, sometimes as far as the hocks. When the displacement is only slight nothing may be seen at the outside – as, for example, when one horn only is inverted into the body of the uterus. It is most common in ruminants, less frequent in the mare.

Signs With an incomplete inversion, the uterine horn that carried the fetus becomes turned in upon itself like the finger of a glove, but it remains inside the passages, and nothing is seen to the outside. The animal is distressed for a time, paws the ground, stamps, lies and rises from the ground frequently, and a series of mild or violent labour pains occurs. She may settle down in a short while, but in a few hours she generally has a repeated attack, when the bulk of the uterus will be expelled to the outside of the body. In the early stages of such a case the real nature of the condition is seldom suspected unless a large pear-shaped mass is seen hanging from the vulva.

The state of the mucous membrane lining of the uterus, which in the prolapse is of course on the outside of the mass, serves as a rough guide to the length of time that has elapsed since the accident occurred. For the first two or three hours the mucous membrane appears moist and of a reddish or brownish colour over the whole surface in the mare and sow. In the cow, sheep and goat, the general surface is red or pink, but the cotyledons show as deep-red mushroom-like eminences scattered over the outside of the tumour. In the bitch and cat there is a wide dark-brown zone. Later, the surface becomes dry – owing to its exposure to the air – and becomes deep reddish, violet or purple, according to the amount of congestion and strangulation.

In the cow the whole of the outer upper surface may be covered with the faeces that are passed as the result of the severe straining. In all animals – but especially in ruminants – parts of the fetal membranes may be adherent to the outer surface of the mass, and can be easily recognised.

The surface is not sensitive to the touch, but any manipulation of the mass is provocative of further straining.

Various complications may occur. The vagina is always displaced when the prolapse is complete; this obstructs the urethra, and dams back the urine.

Treatment Prolapse of the uterus is always an extremely serious condition in any animal, and in the mare and sow very often proves fatal. A percentage of cows and ewes recover, when the prolapse is replaced without loss of time, and when there are no complications.

When treating a case – in whatever animal – it is absolutely necessary to comply with certain essentials as follows:

1. The prolapsed uterus must be protected from further damage. To ensure this the animal must be secured at once, and a large sheet or blanket – which has been previously dipped in mild antiseptic solution – must be placed under the mass, and held by two people so that the tension is relieved from the neck, and so that it cannot be further contaminated or injured.

2. The surface of the organ must be carefully cleansed. For this purpose a clean pail containing a warm solution of potassium permanganate and common salt (1 teaspoonful of the former and 100 g (4 oz) of the latter to 4.5 litres (1 gallon) of water) or diluted Dettol or cetrimide solution may be used. All the larger particles of straw, debris, etc., are picked off, and the smaller pieces removed by gentle washing. Care must be taken not to make the surface bleed.

3. The prolapsed portion must be replaced. To effect this the larger animals may require epidural or general anaesthesia to prevent the powerful expulsive pains that otherwise accompany the process, and make return difficult. When the animal has been anaesthetised the hindquarters should be raised as high as possible by building up the floor with straw bales, by hoisting the hind-legs, or by other means. When the protruded mass is very large and has a distinct neck, the main bulk should be raised to a slightly higher level than the external passage, and a process of ‘tucking in’ is begun near the vulva. This is carried out by the two hands – one at either side – using the hands half closed, so that the middle joints of the fingers come into contact with the uterus. The fingertips should not be employed owing to the danger of laceration or even puncture of the walls. The resistance is gradually overcome and the mass eased along the passages back into the pelvis – a labour that often makes great demands upon the strength and endurance of the operator, and frequently takes an hour or more to effect. Moreover, when once the organ has been returned, unless it is straightened out into its normal position, it may be reinverted a second time.

4. Measures must be taken to retain the uterus in position: the animal may be given an analgesic or a tranquilliser to lessen the chance of subsequent straining; and sutures may be inserted.

Bedding, etc. is arranged so that the animal is compelled to both stand and lie with the hindquarters raised above the level of the forequarters. This throws the abdominal contents forwards, and helps to maintain the uterus in place. It is, of course, mainly applicable to mares and cows. Bandages may prove helpful.

Amputation of the prolapsed uterus becomes necessary when all attempts at its reduction are futile; when the organ has received so much injury or has become so decomposed and gangrenous that it would be certainly fatal to return it to the abdomen; or when prolapse occurs time after time in spite of all attempts at retention.

In a survey of 103 cases of uterine prolapse, 19 cows died within 24 hours of replacement of the uterus.

Hydrops amnii A condition in which the quantity of amniotic (see AMNION) fluid is greatly in excess of normal. It is often associated with a similar condition of the ALLANTOIS, which is sometimes erroneously called hydrops amnii.

Occurring mainly in cattle, and only rarely in other farm/domestic animals, hydrops amnii is often associated with ‘bulldog’ calves and monsters. Sometimes a recessive gene is responsible. It may also occur when crossing an American bison on a cow, i.e. when producing hybrids.

Where oedema of the allantois alone occurs, the cause may be disease of the uterus, especially of the caruncles.

Sometimes oedema of both the fetal membranes and the fetus occurs. In mild cases the condition may not be suspected until calving, when an unusually large amount of fluid will be expelled. Retention of fetal membranes and subsequent metritis may follow.

In severe cases, the cow may lose appetite, appear distressed, be constipated, with rumination adversely affected or depressed. Abdominal swelling may suggest bloat. In extreme cases, the cow may be unable to get to her feet. Cases of dislocation of the hips or backward extension of the hind-legs have been seen in combined fetal and fetal membrane oedema involving amnion and allantois, and uterus (hydrops uteri).

Rupture, involving the uterine wall, may occur before or during parturition in any animal, during the reduction of a torsion or prolapse, or, in the bitch or cat, as the result of a car accident. (See ECTOPIC, PREGNANCY AND GESTATION.)

Torsion, or twisting, of the uterus is commonest in the cow and other ruminants, and rare in other domestic animals. This accident consists of a partial or complete rotation of the uterus around its long axis, and usually involves the neck of the organ.

Signs As a rule there is no indication of the presence of the displacement until parturition is due to commence. The animal is then seen to prepare herself in the usual way, but the preliminary labour pains are exceptionally feeble and separated by long intervals. After the lapse of some hours – when the ‘waterbag’ and other signs of the approaching act should have become evident in an ordinary case – nothing happens. The animal is slightly disturbed, shows an occasional pain, walks around aimlessly, may feed spasmodically, but does not appear to be greatly distressed. This condition may persist for as long as 48 hours. In other cases the animal is very much distressed. It has spasms of violent and painful uterine contraction.

Treatment In the small animals laparotomy is performed, and the twisted organ untwisted. In the cow, it may be possible to rectify the twist by rolling the animal.

Congenital defects (See the diagram under INFERTILITY; also HYDROMETRA.)

Tumours In the rabbit, there is a marked tendency to develop cancerous diseases of the uterus. This is the main reason for spaying does (the operation is usually performed before six months old). The condition is markedly malignant, metastasises readily spread to lungs, liver and other viscera; it is rapidly fatal.

(adjective, Uveal)

This consists of CHOROID, CILIARY APPARATUS and IRIS of the eyeball. (See EYE – The Choroid.)

This is a coat of blood vessels made up of the CHOROID, CILIARY APPARATUS and IRIS (See EYE – The Choroid.)

Anterior Uveal Tract This comprises the CILIARY APPARATUS and IRIS. (See EYE – The Choroid.)

Inflammation of the uvea (iris, ciliary body and choroid coat of the eyeball).

This is a rare condition, but probably inherited. It involves both the skin and eye and is mainly seen in JAPANESE AKITA DOGS. There is an UVEITIS, with inflammation of the eye’s pigmented part. It often leads to retinal degeneration and secondary GLAUCOMA with blindness. The skin and hair around the eyes and muzzle lose their pigment but this may occur after ocular signs start. It is similar to the human condition of Vogt-Koyangi-Harada which is associated with genetically determined tissue types.

The small downward projection that is found on the free edge of the soft palate of the pig. It is not present in the other domesticated animals.