After I painted the first, I became fascinated with her innocence. So I did a few more; I guess I was trying to see who was this face so evil, who had done all she was so rightfully accused of.

–Ricardo Pustanio, painter of the famous Haunted House Delphine Lalaurie portrait

As the truth is slowly uncovered, it will be interesting to look at how the story has been viewed and reported since the night of the incident. The Bee articles are available online and in this book, but there is a lot more material we have not yet revealed. By following these narratives, one can see Madame Lalaurie growing in myth and legend.

As we mentioned in the fifth chapter, an article published in Le Courrier Etats-Unis on December 8, 1838 (found at Northwestern State University of Louisiana), written by L. Souvestre, tells of what seems to be an eyewitness report of the events in the Lalaurie Mansion by a Methodist minister identified as “Dr. Miller.” This article places Madame Lalaurie (known in this story as Madame de Larcy) at the estate of Henri Vrain, her in-law through Delassus, in the Paris suburbs of Saint-Cloud, France, not long after the fire. The fact that these relatives weren’t commonly known by most storytellers gives the story a boost of credence.

However, the structure and the writing style are more indicative of a short story, and no “Dr. Miller” can be identified as an actual historical character.

This article or short story seems to reinforce (or perhaps invent) some of the more popular details that turn up in New Orleans ghost tours: the “coachman who glowed with health,” the story of Madame passing her glass of wine to a slave and the emaciated, fearful slaves who initially made people wonder what was going on in the mansion.

In addition, this story gives a solid reason for a slave to start the fire, as it was her child who fell to his (or her, as more commonly told) death while being chased by Madame.

There are many differences between this story and popular legends. “Dr. Miller’s” account has a young boy, Mingo, as the child who was chased off the roof in 1833 instead of a young girl who pulled a tangle in her mistress’s hair and incurred Madame’s wrath. He also cites Madame Lalaurie as thrice a widow when these events happened. Louis Lalaurie was not dead in 1834, and multiple eyewitnesses place him at the scene of the fire, annoying his neighbors. Madame is described as young when she would have been at least fifty in 1834. Her daughters are described as children. They were, in fact, young women in 1834. Her young son by Louis Lalaurie was the only child in the house.

Whether this melodramatic piece is fiction (which the authors are inclined to believe) or an embellished version of the truth, it shows that the Lalaurie tale was not only alive and well in 1838 but also that, four years after the incident, it was already changing shape. (Read the entire L. Souvestre story at www.mad-madame-lalaurie.com.)

The first written non-eyewitness account of the story is attributed to Harriet Martineau (1802–1876), a British author, abolitionist and philosopher. During her lifetime, she was recognized as a controversial journalist, political economist, travel writer and feminist. Her Retrospect of Western Travel in three volumes chronicles her visit to the United States in 1838–40. She traveled extensively, visiting almost every region of what was the United States at that time.

Her storytelling was brilliant. She vividly evoked many scenes of American life for her British audience. However, she often seemed to base her observations on what she was seeing at the moment; for example, she described New Hampshire as dark and desolate, but she was there during winter. She reported what was told to her by locals with no research into the actual events and as seen through the thick lenses of an abolitionist and feminist.

Interestingly enough, her account of Madame Lalaurie is seen only through the eyes of the abolitionist. No consideration of Madame Lalaurie as a woman in Creole society is given. That being said, her version of the story is quoted or repeated in almost every piece that covers the Lalaurie story.

Martineau began her account by describing the beautiful setting of the road along Lake Pontchartrain and then segued into the following: “It was along this road that Madame Lalaurie escaped from the hands of her exasperated countrymen, about five years ago.” A fine way to start a tale of gothic horror, even one that happens to be true.

One of the initial mysteries, that of why Dr. Lalaurie is minimized in folklore and is seldom mentioned as a co-perpetrator of the torture, originated in Martineau’s narrative: “Her third husband, M. Lalaurie, was I believe, a Frenchman. He was many years younger than his lady, and had nothing to do with the management of her property; so that he has been in no degree mixed up with her affairs and disgraces.”

Whether or not that was true, Ms. Martineau’s compelling account made sure that the image of Dr. Lalaurie as a passive background figure became stuck in popular folklore.

The lawyer who was allegedly concerned about the rumors of maltreatment of the Lalaurie slaves was a friend of Ms. Martineau’s. Because he was American, and thus not an insider in Creole society, he sent his young Creole student to the Lalaurie house to inform the Lalauries of the Code Noir restrictions. The clerk supposedly returned to his employer starry-eyed and utterly charmed by Madame. This part of the Lalaurie story is told in most every version, oral and written. The identity of the lawyer is never revealed. Martineau referred to him only as “a friend of mine, an eminent lawyer.”

Her next bit of narration told of the young slave girl, about eight years old according to Martineau, who was chased onto the roof by Madame and fell to her death in the courtyard. She told this as a secondhand account from a witness whose property adjoined the Lalaurie house. Martineau alleged that the little body was carried off by grieving slaves and then buried in the courtyard where she died. Martineau went on to say that an inquiry was opened to investigate the death and that Madame was found guilty of cruelty. The judge ordered that nine slaves, “who were forfeited according to law,” be removed from the Lalaurie house. She claimed that the Madame used family connections to purchase these same slaves back for the sole reason of imprisoning and torturing them, “for she could not let them be seen in a neighborhood where they were known.”

It is assumed by many storytellers and writers that the seven slaves who were pulled from the fire were these very slaves. Although this is an enduring part of the legend, its veracity is somewhat dubious. The entire story was told secondhand and even thirdhand to Harriet Martineau. Our later investigation revealed that no court records exist for the death of the slave child nor of any legal judgment against Madame.

One tidbit of gossip that Martineau included, which is not commonly included in the lore, is that Delphine was an abusive mother:

It appears that she beat her daughters as often as they attempted in her absence to convey food to her miserable victims. She always knew of such attempts by means of the sleek coachman, who was her spy. It was necessary to have a spy, to preserve her life from the vengeance of her household: so she pampered this obsequious negro, and at length owed her escape to him.

Interestingly, author Barbara Hambly described Madame’s daughters as abused in her excellent novel Fever Season, although the abuse seems to be more mental than physical.

We doubt the factuality of the physical abuse, at least. Delphine Lalaurie’s daughters remained faithful to her throughout their lives, often traveling and living with her. Letters between Madame and her girls indicate a warm relationship. (As an aside, it is not uncommon for psychopathic or sociopathic individuals to love their own family members, as much as they are capable. Many spouses and relatives of psychopaths are utterly surprised that their loved one could have ever done such bad things—they never saw that aspect of the perpetrator’s personality.) Martineau’s description of the fire differed from most retellings. She stated that it was extinguished fairly quickly and that the neighbors took advantage of this to break into the “outhouse” (outbuilding) to satisfy their curiosity about the rumors of cruelty.

She painted the Lalauries’ escape as being Bastien’s idea, as his mistress was so self-absorbed that she had no idea that a bloodthirsty mob was ready to tear her apart. The description of her escape is exciting and dramatic. Martineau’s description of the mob reaching the lake too late to catch Madame and instead taking their vengeance out on the horses and, most probably, Bastien is frequently quoted (though unverified).

Martineau related that Madame Lalaurie escaped the howling mob and fled to France but did not stay in one place for long before she was recognized and had to run again. Madame, she believed, “is supposed to be now skulking about in some French province, under a false name.”

This rumor of disgrace and exile is found throughout the later legends but is probably not true. Madame would not have had much reason to hide her identity in France, where she could not even be charged with a crime.

Martineau ended her account with a paragraph about the mob setting off to find other cruel masters and distributing circulars. Martineau could “never get out of the way of the horrors of slavery in this region.” That may or may not have been true. There are no newspaper accounts of mobs randomly searching Creole homes for cruel masters. It seems doubtful that such a thing would have been permitted by the New Orleans police, who were almost entirely French Creole at the time.

Martineau’s tale set the standard for the vilification of Madame Lalaurie. She set Dr. Lalaurie aside as ineffectual, setting the blame squarely on the shoulders of Delphine. Her dramatic descriptions, which she says she collected from eyewitnesses, defamed Madame Lalaurie forever. Martineau gave us a spectacular narrative from just five years after the events, but most of what she reported is hearsay. As for the veracity of eyewitnesses, just speak with any law enforcement officer. Eyewitnesses are considered by many in police work to be the least reliable source of evidence. The brain plays tricks on us. We see what we expect to see, and what we hear about an event can color our memories of it later. Fortunately or unfortunately, Martineau helped set the stage for the story to grow from a shameful case of cruel abuse to an epic Grand Guignol horror show.

Historian Castellanos wrote a history called New Orleans As It Was: Episodes of Louisiana Life, which dedicates a chapter to the Lalaurie story. He took some time to research and analyze the story, probably for the first time since the events occurred. He was a contemporary of George Washington Cable’s, publishing in the late 1890s. Castellanos added some historical documentation to the tale:

The proprietor of the New Orleans “Bee” wrote: “We saw where the collar and manacles had cut their way into their quivering flesh. For several months they had been confined in those dismal dungeons, with no other nutriment than a handful of gruel and an insufficient quantity of water, suffering the tortures of the damned and longingly awaiting death, as a relief to their sufferings. We saw Judge Canonge, Mr. Montreuil and others, making for some time fruitless efforts to rescue those poor unfortunates, whom the infamous woman, Lalaurie, had doomed to certain death and hoping that the devouring element might thus obliterate the last traces of her nefarious deeds.”

He also corrected what he believed to be erroneous information in previous accounts and backed up his research when he could. For example, a rumor had been going around that many of the rescued slaves died after being fed because they were just too weak to handle nutrition after months of starvation. Castellanos refuted this:

Two thousand persons, at least, convinced themselves during that eventful day by ocular inspection of the martyrdom to which those poor, degraded people had been subjected, while the ravenous appetite with which they devoured the food placed before them fully attest their sufferings from hunger. None of them, however, died from surfeit, as it has been erroneously alleged. Numberless instruments of torture, not the least noticeable of which were iron collars, “carcaus” with sharp cutting edges were spread out upon a long deal table, as evidences of guilt.

He agreed with Martineau on several points, though, including the idea that the fire was purposely set by a slave: “Among them, a woman confessed to the Mayor that she had purposely set fire to the house as the only means of putting an end to her sufferings.”

Many tellers of this tale do not look at the activities of the police during the three days after the fire. Some say that all the manpower in New Orleans was needed to protect the Lalaurie house from being reignited and burned to the ground. No account has been found that tells if there was an active effort by law enforcement to capture Madame and Dr. Lalaurie as they fled. Castellanos shined a small light onto what the city authorities were considering:

It was said that Etinue Mazureau, the Attorney General, had expressed his determination to wreak upon the guilty parties the extreme vengeance of the law. But when the shadows of night fell upon the city, and it was ascertained beyond a doubt that no steps in that direction had been taken and that powerful influences were at work to shield the culprits, their fury then knew no bounds and assumed at once an active form.

One item that Castellanos cleared up is whether the bones of the murdered slave girl (and perhaps other victims) were found in the courtyard:

The story that human bones and among others those of a child who had committed self-destruction to escape the merciless lash, had been found in a well, is not correct, for the papers of the day report that acting under that belief, the mob had made diligent search even to the extent of excavating the whole yard, and had found nothing.

Henry Castellanos is a must-read for the Lalaurie enthusiast. He closed his chapter with his belief about the state of the house, as it stood at the time of his writing:

As a school house; as a private residence, as a factor; as a commercial house and place of traffic, all of these have been tried, but every venture has proved a ruinous failure. A year or two ago, it was the receptacle of the scum of Sicilian immigrants, and the fumes of the malodorous filth which emanated from its interior proclaimed it what it really is, “A HOUSE ACCURSED.”

This highly entertaining (if extremely racist) ending to the account makes a dramatic denouement to Castellanos’s story. However, it is a little surprising that a writer who was so careful with his research into the facts would end on a superstitious note. This just proves that the Lalaurie story affects all who hear it—not just intellectually but at the gut level, the fearful, irrational level where monsters are real and ghosts haunt the house of pain.

The American novelist George Washington Cable was probably the most famous writer to spread the Lalaurie legend. Born in Louisiana in 1844, Cable fought for the Confederate army and later became a journalist. His stories of Creole life, before and after the Civil War, painted an incredible picture of pride, opulence, racism and money. His eye for detailing the “battle” between the Americans and French Creole was remarkable, especially in his novel The Grandissimes. He conveyed a sense of disapproval toward the racism still present in Louisiana after the War Between the States. Cable eventually moved to Massachusetts and became friends with Mark Twain. They toured together doing book lectures.

George Washington Cable shared tales of Creole culture and its secrets and mysteries with a large American audience. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

In his book Strange True Stories of Louisiana, Cable was one of the first to relate the story of the haunting of the Lalaurie house. He described the basics of the story, mostly sticking to the facts. (It is notable that he did not include any “medical experiment” injuries in the list of tortures suffered by the slaves.) He claimed that Judge Canongo took leadership to look for the household slaves in the garret rooms. He cited neighbors Montreuil, Fernandez and Lefebrve as assisting in the rescue. These accounts are backed up with original documents and depositions given after the incident in 1834.

Initially, rival Louisiana historian Charles Gayerré referred to Cable as “no more than a malevolent, ignorant dwarf,” but Cable’s popularity and fame as a Creole historian climbed. Gayerré, who was a notorious Creole loyalist in his views of Louisiana history, joined with other New Orleans elite families and led a campaign to defame Cable. Included in his attacks were “sizzling editorials” in the New Orleans Bee and a spurious story that Madame Lalaurie had refused to receive Cable in her house because he had “colored blood.” Gayerré claimed that Cable wrote his story of the “Haunted House in Royal Street” to get even for this slight. The story is laughable, considering that Cable was born in 1844—a full ten years after Madame and Dr. Lalaurie fled New Orleans, making him about thirteen years old when Madame Lalaurie died, according to historian Christopher Benfey.

As Cable’s popularity grew with American audiences, his fate was sealed among the Creole families in New Orleans. Benfey quotes Louisiana historian Grace King, who wrote that “Cable proclaimed his preference for colored people over white and assumed the inevitable superiority—according to his theories—of the quadroons over the Creoles.”

Obviously, this caused him to be persona non grata among the Creole elite. To his credit, Cable didn’t seem to care.

Cable published and traveled, and he never backed down from his revelations about the inner workings of Creole society. This earned him the title of “the most cordially hated little man in New Orleans,” at least according to New Orleans author Joseph Pennell, quoted by Benfey.

The ghost stories surrounding the Lalaurie incident are perhaps the pieces of the story that are the most repeated, most widely spread and most creatively embellished. You won’t find a haunted New Orleans tour that doesn’t include ghosts along with the grisly details of torture and mayhem. If you ask any longtime citizen where to find the most haunted house in New Orleans, they’ll direct you to the house on Royal Street.

Enter Jeanne DeLavigne, who wrote Ghost Stories of Old New Orleans in 1946. It not only set the standard for tales of hauntings in the Lalaurie house, but it was also quite possibly responsible for some of the gorier embellishments on what the rescuers found during the Lalaurie house fire of 1834, including the medical experiments and buckets of body parts. There is no documentation to back up these aspects of the story. DeLavigne wrote a horror story, not a history:

The man who smashed the garret door saw powerful male slaves, stark naked, chained to the wall, their eyes gouged out, their fingernails pulled off by the roots; others had their joints skinned and festering, great holes in their buttocks where the flesh had been sliced away, their ears hanging by shreds, their lips sewed together, their tongues drawn out and sewed to their chins, severed hands stitched to bellies, legs pulled joint from joint. Female slaves there were, their mouths and ears crammed with ashes and chicken offal and bound tightly; others had been smeared with honey and were a mass of black ants. Intestines were pulled out and knotted around naked waists. There were holes in skulls, where a rough stick had been inserted to stir the brains. Some of the poor creatures were dead, some were unconscious; and a few were still breathing, suffering agonies beyond any power to describe. [DeLavigne quoted the firemen entering the house.]

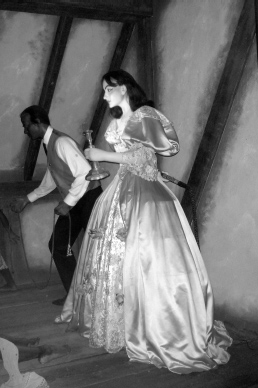

Image from the DeLavigne book of a torture victim hanging upside down.

This book, sadly out of print, is a classic of New Orleans ghost story literature. If you find a copy, consider yourself very lucky.

Interestingly enough, firsthand stories of hauntings in the Lalaurie house have appeared in newspapers and periodicals over the years, particularly at Halloween. This States Item report from June 16, 1969, notes an appearance:

Zella Funck lives in the famous “Haunted House” at 1140 Royal St. “My poltergeists are just playful,” she declares blithely. “They’re not around every day, but they do surprise visitors.”…The ghost, whom she says she has seen twice, is a romantic figure of a man. “I’ve watched him for several minutes in a full-length mirror before he faded away. He’s about 5’9”, about 170 lbs, has a reddish clipped beard, and wears a creamy beige felt hat turned up slightly, with a cord around it.”

This Times-Picayune item from August 11, 1974, reports another:

As recently as 14 years ago, a long-time resident of one of the small apartments within the building declared emphatically that he had heard strange sounds near his room for as long as he had lived there—footsteps running along dim passages, mournful sighs and, at least once, a smothered scream. He didn’t bother to investigate, he said, and so the spirits—or whatever they were—hadn’t bothered him.

Of course, if you search for “Lalaurie ghost stories” on the Internet, you will find a veritable treasure-trove of material. Like most Internet content, it is to be taken with a huge grain of salt. But searching for Madame on the web from time to time is an entertaining way of finding out how the legends have most recently been adapted.

There are two images of Madame Lalaurie that float through the Internet. One is a realistic-looking painting depicting Delphine in an 1880s-style dress. The other painting is more eerie, painted in unsettling reds and blacks. Both paintings were created by the same New Orleans artist, Ricardo Pustanio.

Pustanio’s first portrait of Madame Lalaurie is the most commonly found image of Madame on the Internet. Very similar to a 1934 portrait published in the Times-Picayune, the red and black painting of the infamous Madame Delphine Lalaurie was painted in 1997 and has grown its own legend. As spooky as it is, there is nothing strange about its creation or the reasons Pustanio decided to paint it. “At the time I used whatever image of her I could find to do the work from,” said Pustanio, both on a website and in his interview with one of the authors. “I even went to the Musée Conti Historical Wax Museum and questioned them about her appearance they did in wax.”

With no detailed description of Madame Lalaurie in the chronicles of history (other than the often-repeated comment that she was beautiful), Pustanio and the Musée Conti were on their own in creating her image.

Pustanio told the authors in an interview that he was asked to create this image by a resident of the Lalaurie house. This gentleman wanted to have her portrait in their apartment as a touchstone with the building’s past. Besides, they said, it would make a great conversation piece. Pustanio obliged, creating a haunting, unforgettable image. The painting was perhaps more haunting than Pustanio intended, for it gathered its own reputation for being haunted.

After they hung it on the wall, the piece took on a life of its own, according to the portrait’s owners. “The resident began to hold séances for his friends and even tourists and paranormal investigators, who always are trying to get a glimpse inside the haunted mansion,” said Pustanio. “To their astonishment the painting would actually rock on the wall and even fall loose from the wall, hitting the floor with a great thud.”

The owner eventually became frightened by the painting. He reported smelling smoke, having objects in his apartment moved around by unseen forces and other strange phenomena. He gave the portrait to one of the other tenants of the mansion. She hung it proudly, but she also started having problems with the painting. She heard pacing footsteps and strange sounds. The portrait’s eyes followed her across the room. Cold hands touched her. When she started hearing the painting whisper to her, she brought in a paranormal investigator to document the incidents. (The complete story of the haunted portrait can be read at the Haunted America Tours website.)

Pustanio often heard the story of a haunted painting bandied about, but he did not at first realize that the painting in question was one that he had created. “[N]ever did I think the Haunted Painting was something that I had done,” the artist was quoted as saying. “I’ve done a lot of things in my life that people say are haunted. I personally don’t think I am haunted. Nor does what I do attract ghosts, or is intended to be haunted.”

“I just think outright some people connect with artists, because we put strong emotions into our works,” he continued. “And isn’t a haunting basically supposed to be just that, strong emotions of the dead manifesting themselves?”

During his interview with the authors, the artist commented that he was very happy about the portrait being his, even though it did nothing of a supernatural nature when it was returned to him by its second owner. “It is great publicity to paint a haunted portrait,” he said.

Pustanio went on to say that he found the portrait a new home and that the new owners will not discuss the portrait. When Pustanio was asked why his portraits of Madame depict her in the wrong period costume, he replied that this detail was requested by the patrons. No one wanted her in the lovely French Empire–style dress that she would have worn to grace the salons of Creole New Orleans. They wanted Victoriana, perhaps because the high collars and dark ruffles are seen as more gothic. He also noted that people always describe Madame Lalaurie to him as a tall woman, and he envisioned her as smaller with dark hair and eyes. Perhaps that was true, or maybe she retained the Irish fairness of her father’s side of the family. Pustanio is the only one, besides the Musée Conti Historical Wax Museum, that has so far put a face to this legend.

An interesting aside: during the interview, Pustanio revealed that his interest in the Lalaurie family stems from a personal connection to the story. His family historically owned land around St. John’s Bayou, where Delphine was said to have escaped the screaming mob.

Pustanio’s family ran a fish business that focused on the Creole elite. Pustanio still graces the Mardi Gras parades with his imaginative floats, winning awards almost every year. He is also available to paint by commission if you want your own portrait of the mad Madame Lalaurie or of her Devil Baby of Bourbon Street.

The Musée Conti Historical Wax Museum, located at 917 Rue Conti in the Vieux Carré, displays a wax rendition of Madame Lalaurie. When the authors asked around the shops and bars of the French Quarter, people often called the likeness of Madame Lalaurie “obscene.” Most people on the street believe that the wax image shows Madame whipping the slave child before the child fell from the roof of the mansion.

In fact, the museum has Madame dressed in a pink and white dress from the 1830s, holding a candle up while her slave, Bastien (we assume), is shown whipping two slaves who are obviously starved and chained in the attic. It has not been changed since the museum opened in the 1970s.

Not a wholesome image, but it is certainly a different tableau than the one at least a dozen people described to the authors. It’s fascinating that such tales are being passed around and embellished regarding an in-town display that can be viewed at any time. Perhaps the average citizens of New Orleans have no taste for tourist destinations like the wax museum. Or maybe they’re just too tired of the hideous story to want to see it played out in realistic wax figures.

One of the few attempts to put a face to Madame Lalaurie, the Musée Conti Historical Wax Museum in New Orleans shows Madame and her faithful servant beating starved slaves. Photo by Victoria Cosner Love.

In 1934, the Times-Picayune published an article on the 100th anniversary of the Lalaurie fire, featuring a portrait of a lovely woman. The articles reported that the woman in the portrait is Delphine Lalaurie. The face looks hauntingly similar to Pustanio’s images.

Dozens of websites are dedicated to Madame Lalaurie. According to the many pages of the World Wide Web, Madame Lalaurie is guilty of serial killings, sending voodoo curses, raising a Devil Baby, turning her slaves into zombies and plenty of other horrid but rather ridiculous and unbelievable crimes. Most websites quote one another or the same Bee articles sourced above, over and over. Many websites relate one variation or another of the core story, with some embellishment and artistic license. Some seem to espouse ideas pulled from the webmaster’s own head, not based in fact, rumor or even logic.

A Madame Lalaurie portrait as shown in a 1934 newspaper article. Could it be?

You’ll find a list at the end of this book of lore-related Lalaurie sites. Don’t visit them for solid information, but definitely visit them. You’ll find some outrageously entertaining material. These sites are a must-see for enthusiasts of the Lalaurie legend.

In Fever Season, a novel of historical fiction, author Barbara Hambly enmeshes her hero, a free man of color named Ben January, in the Lalaurie story. Her research into the subject was meticulous. Her portrait of New Orleans in 1834 is amazingly realistic and utterly engrossing.

Hambly takes a definite opinion on Madame Lalaurie, describing her as a sexual sadist almost solely responsible for the atrocities against the slaves. Whether or not that was the case, she portrays Delphine beautifully as a coldhearted, controlling sociopath, which could well have been the truth.

Hambly even notes that Dr. Lalaurie was working on medicine to help correct malformations, as we noted in the fourth chapter. This is a little-known historic tidbit and illustrates the incredible level of research that went into her book. This novel is by far one of the best and most entertaining fictional accounts of the Lalaurie story.

One would think that Hollywood would find the Madame Lalaurie story irresistible. However, we have not been able to find a single historical drama about the incident.

We did find a low-budget horror movie set in contemporary times but based (loosely) around the Lalaurie legend: The St. Francisville Experiment, from Trimark Pictures, 2000. The film features four young ghost hunters entering a “haunted house” in St. Francisville, Louisiana, where Madame Lalaurie was said (according to the movie) to have continued her atrocities after fleeing New Orleans in 1834. The film was shot at the lovely Ellerslie Plantation, which is actually located outside of St. Francisville. This film is a Blair Witch Project–style faux documentary, shot with handheld video cameras. Although the town of St. Francisville does have a number of ghost stories connected with it, including the famously “haunted” Myrtles plantation house, there are no actual stories connecting it to Madame Lalaurie.

The Lalaurie house and its supposed hauntings have been mentioned on a number of documentary and reality TV programs. The legend was showcased on the History Channel’s Haunted History series, and the Lalaurie story comes up often in “Ghost Hunter” and “Most Haunted” TV shows. Watch your TV listings, particularly around Halloween, and you’ll most likely find something about the Lalauries.