The slaves were the property of the demon in the shape of a woman whom we mentioned in the beginning of this article. They had been confined by her for several months in the situation from which they had thus been rescued and had merely been kept in existence to prolong their sufferings and to make them taste all that the most refined cruelty could inflict.

–New Orleans Bee, April 1834

There is nothing funny about what happened to the unfortunate souls trapped in the garret of the Lalaurie house in 1834. That was a tragic and horrible event. But if one were to look at every aspect of the legend, including the more outlandish parts, it starts to get just a bit ridiculous.

To play devil’s advocate, your authors would like to present a worst-case scenario: what if it’s all true? Every rumor, every tale and every gory detail? Let’s take a look.

In our worst-case alternate reality, Delphine has been wicked since birth. She slyly managed to kill both of her previous husbands in order to inherit their money. She found a soul mate in Louis Lalaurie—they both have a taste for blood.

Delphine and Louis Lalaurie are serial killers. They have been killing slaves for years, from the time they moved into the house on Royal Street. Their reasons for killing are different, but they are equally deadly. When a slave perishes at their hands, he is buried beneath the floorboards of the house or perhaps taken out to the swamp in the dead of night and dumped as food for the alligators. They also keep a number of slaves chained in the attic at all times so they are available if either Lalaurie suddenly has the impulse to kill or torture.

“We only permit masters, when they shall think that the case requires it, to put their slaves in irons, and to have them whipped with rods or ropes.” From the Louisiana Code Noir, 1724.

Madame kills and maims slaves because she is naturally cruel and because she was driven insane by the murder of her parents, who died in a slave uprising. She is now completely mad and a sadist—perhaps even a sexual sadist. She takes perverse pleasure in starving her slaves and watching them waste away before her eyes. She glories in the fact that their lives are entirely in her hands.

She flogs her slaves mercilessly for the slightest mistake. She pours salt water into their wounds, binds their mouths shut and coats them with honey so that ants will devour them. Anything that pops into the fetid jungle that is her mind she is likely to perpetrate on her poor, hapless bondsmen.

Madame puts forth an image of tranquility and social grace. She is beautiful and charming, and her parties are legendary. All of Creole society loves and envies her. Delphine and Louis live in their stylish Creole mansion with two of Delphine’s adult daughters from her marriage to the handsome pirate, Jean Blanque, and with her young son with Louis Lalaurie. She takes a perverse pleasure in maintaining a perfect façade, while her private life is a twisted hell of sickness and brutality.

Bastien, Madame Lalaurie’s driver, is a willing accomplice in her crimes. He has no compassion for his fellow slaves and will beat them just as readily as Madame will. He is utterly loyal to Delphine—the moment she tells him to do something, he does it. He works as a spy for Madame. If her waiflike daughters try to sneak food to any of the slaves, Bastien tells Madame, who beats the girls without mercy. He lords his power over the slaves as much as any overseer would.

Why is he so loyal to his cruel mistress? Is it simply because she feeds him well, clothes him beautifully and treats him with kindness? Or is it something more? Perhaps he shares her taste for sadism. And perhaps he and Madame are lovers. Once again, Delphine defies society’s norms, twisting them to fit her self-centered and perverse inner world.

Louis Lalaurie does not consider himself a sadist. He is a doctor, and he conducts experiments out of scientific curiosity. He started out with good intentions. He drafted the occasional unlucky slave to be a test subject for his work in curing skeletal deformities. But once he realized that he had utter power and control over these people, all self-control fled. He does anything to the bodies of his slaves that enters his imagination. And his imagination is very vivid.

Can a person survive if you drill a hole into his head? What happens if you stir his brain with a stick? How much skin does a person need? How much can you peel away before she dies? Can the human body adapt if you break every large bone and reset them at bizarre angles? Will she still be able to move? If you cut the sexual organs from a person of one sex and sew them onto another, can you change the sex of the subject?

The doctor’s experiments are extremely messy. Buckets of body parts litter the attic. He has asked Bastien to dispose of them, but the haughty servant answers only to Madame. No matter. Perhaps the doctor will think of some use for the severed limbs.

In addition to his surgical experiments, Dr. Lalaurie has been experimenting with “zombie powder” in an attempt to create the perfect, utterly obedient slave. He is supplied with the highly toxic ingredients by Marie Laveau, New Orleans’ reigning voodoo queen. His subjects are Marie’s enemies, as well as his own slaves. Time and time again he has administered the powder to bound and helpless subjects. Unlike his predecessors in Haiti, he has not yet succeeded in creating a docile zombie.

Most of his subjects simply die after suffering extreme pain and paralysis. Some go mad, ranting and raving at invisible tormentors. These subjects Dr. Lalaurie has to kill quickly to prevent them from raising too much ruckus. Some fall into a deep, staring unconsciousness and never awaken. These people are used in Dr. Lalaurie’s surgical experiments. Madame Lalaurie is not interested in them. She only likes victims who are able to scream.

The Musée Conti Historical Wax Museum displays a wax presentation of Marie Laveau providing goods for a bride. Photo by Victoria Cosner Love, permission of Musée Conti Historical Wax Museum.

In addition to the abattoir in their attic, the Lalauries have other secrets. One of them is the Devil Baby of Bourbon Street, who lives in a small, dark room at the back of the house. This monstrous, deformed child was given to Delphine by Marie Laveau. The voodoo queen claims that the child was cursed, born of a union between a fine Creole lady and a swamp devil. Judging by the unearthly howls and shrieks the little creature emits, the Lalauries suspect that she may be right.

When the baby was baptized, Madame Lalaurie stood as his godmother. She and Marie Laveau each have their own motives for keeping the baby alive. Laveau wants the child for blackmail and to add to her own fearful reputation. Madame just finds him amusing.

A “Devil Baby” skull sculpture. The “Devil Baby” of Bourbon Street has inspired generations of artists and ghost hunters. Authors’ collection.

Delphine delights in the Devil Baby. She finds his screams and spasms endlessly amusing. She spends hours watching the child, petting him and feeding him bloody bits of raw meat. Louis, too, is fascinated with the baby. He would love to dissect it, but Delphine shoos him away.

Delphine’s sanity seems to be slipping further away. She starves even the slaves who serve her in the house. Visitors have begun to whisper about their gaunt, miserable appearance. When no one is visiting, she forces the slaves to go naked or shirtless, simply to humiliate them. Her daughters, always by her side, seem timid, pale and scared. Her temper is as volatile as an angry alligator’s. The slightest misstep sends her into a fury. She keeps a bullwhip in her boudoir, and she is an expert with it.

One evening, Nina, a little slave child, accidentally pulls Madame’s hair while brushing it. Madame goes mad with fury, chasing the girl to the roof of the house and lashing her with the bullwhip. The terrified Nina, given the choice between the raving Madame and the cobblestoned courtyard below, chooses death. Her little body strikes the stones with a sickening crunch. Madame stares dispassionately down at her for a moment and then goes back inside the house. The servants wait until Madame is abed. Quietly, like shadows, they carry the child’s broken body to the kitchen. The women tenderly wash her while the men dig a shallow grave by the well in the courtyard.

Nina’s is not the first corpse to be interred there. It is almost certainly not the last. But someone has had enough. Nina’s grandmother, Rachael, an old kitchen slave, seethes with fury. She vows revenge against her mistress.

What Delphine does not know is that a horrified neighbor witnessed the chase and the whipping and hid her eyes as little Nina plummeted to her death. The authorities are called in. Delphine is called to court, where she perfectly balances her false grief for the “accidental” death of the child with her well-practiced charm. The judge, a relative of Delphine’s, wants to dismiss the case, but the city is simmering with rumors about the incident. He orders Delphine to pay a fine of $300, which she can well afford. He also orders her remaining slaves, with the exception of Bastien and Rachael, to be removed from her property and sold.

Madame does not appreciate the negative press, but it takes much more than that to rattle her. She quickly and quietly arranges for another relative to buy the slaves back for her.

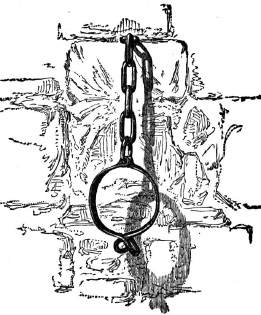

She blames the slaves for her public embarrassment. Thick, heavy, spiked chains are attached to their necks, wrists and legs, and they are locked in the attic to await her “attention.” If her treatment of them was bad before, it now escalates to horrifying proportions.

Delphine is particularly irritated with Rachael, the grandmother of the dead slave child Nina. Rachael has always been a magnificent cook, making Delphine’s friends jealous with the culinary treats that roll from her kitchen. But now Rachael grows defiant, refusing to cook. One minute Rachael can be found mourning pitiably for her lost grandchild and the next raging for vengeance. Madame, unconcerned as usual, chains her to the big kitchen stove and tells Rachael that she will stay there until she decides to resume her duties as cook.

There Rachael remains, starved, the chains chafing her papery old skin. Each time the door to the courtyard opens, she views her granddaughter’s grave and hears in her mind the sound of the child hitting the stones. Finally, she can stand it no longer. She stokes up the oven until it is a hellish inferno and sets fire to the house. Rachael means to make her mistress pay, even if it means her own agonizing death.

Neighbors and friends spot the smoke and rush over to help. First they try to pull old Rachael from the kitchen, but it is too late. She screams out the back window for revenge, but the chains hold her fast, and she is consumed by the ravenous flames. She dies, cursing her mistress with her last breath.

The rescuers rush into the main house, attempting to pull Madame and Dr. Lalaurie to safety. To their surprise, the couple will not leave. They begin coolly ordering their neighbors to save this treasure and that from their beautiful collection of art and furniture. The fire has consumed the dining room by now, directly above the kitchen chambers.

A house this large does not run itself, and it is common knowledge that Madame bought back her slaves.

“Where are they?” the crowd demands. “Where are the slaves?”

Madame glibly rebuffs them, suggesting that they save a valuable painting instead. She seems as calm and good-natured as she was at her many glittering parties.

Dr. Lalaurie, on the other hand, is flustered and irritable. He, too, refuses to tell the rescuers, including the venerable Judge Canongo, where the slaves are located. He orders his friends and neighbors to mind their own business.

The judge is torn between the rumors he’s heard and the respect that the Lalauries’ place in society commands. He hesitates and then resumes helping to carry the valuables out of the house.

Soon a New Orleans fire brigade arrives. The men quickly locate an attic room with a heavy padlock. When the firemen demand the key, Madame claims to have lost it. The strong, competent men break the lock and throw the heavy door open.

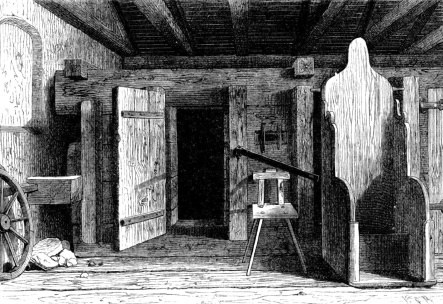

Many Creole mansions had attics used to store secrets or old clothes.

They walk into a scene from hell. These men have been on the scene of many a fire and road accident. They have seen plenty of gore in their time. But what they see before them defies description. They might have frozen in horror if it were not for the smell, which pushes them back like a force of nature, causing these strong men to retch and vomit. The smell of death is overpowering, and it is mixed with the foul odors of infection, urine, feces, fear and filthy, unwashed bodies.

They see the grotesque results of Dr. Lalaurie’s experiments. The crab woman, the peeled “caterpillar” woman, the sex change couple and the man with the hole drilled into his head, maggots crawling on his face. Some of the victims seem to have been mutilated for no obvious reason at all, the flesh stripped from their buttocks, knees and elbows. The floor is sticky with old blood and slick with puddles of fresh new gore. Buckets of body parts are strewn about the room as casually as if they are baskets of corn. The firemen retreat in horror and nausea.

Madame’s nosey neighbor and second cousin, Montreuil, tells Judge Canongo that he knows where there are more slaves. He leads the judge and two others to an attached room.

These are the victims of Madame Lalaurie. Their bodies are scored and striped with the lash. They are starved, concave bellies seeming to touch their own backbones. Some have their mouths and eyes bound with filthy, offal-soaked cloth, presumably to muffle their screams. Some of the chained slaves have been coated with honey. Ants, cockroaches and rats gnaw away at their helpless flesh.

A few of the chained slaves are dead and clearly have been for some time. The rescuers find themselves feeling that the dead slaves are the lucky ones.

The strong men of the New Orleans fire department move in quickly, along with the braver men from the neighborhood. They whisper comfort to the miserable slaves as they unlock their chains.

Some of the slaves die in the attempt to move them. Their poor bodies have taken more punishment than they can bear, and their hearts give out. A few of the slaves have been driven utterly mad. The woman with her limbs broken and reset at horrible angles scuttles into the corner, refusing to let anyone approach her. She lets out a high-pitched, hissing scream whenever a would-be rescuer gets close. Some of the slaves are toxic with infection, burning with fever and ranting. Some cannot seem to pull out of the hopeless terror that has gripped them for so long. One poor soul runs for the attic window as soon as his chains are unlocked. He (sometimes a she in other versions) smashes through the glass and flings himself out the window to his death in the courtyard below.

By this time, the crowd outside the Lalaurie Mansion has grown huge. There is a collective gasp when the first of the pathetic, filth-encrusted, bloody and mutilated slaves is carried from the attic. A few kind souls run and get food for the starved slaves. Only a few of the victims are strong enough to eat, and they immediately howl in pain and perish. The food is too much for their severely deprived bodies.

As these hapless victims are slowly and painfully removed from the room, the crowd’s anger grows. Some city officials in the crowd decide that it would be best for the safety of the slaves to take them to the Cabildo, some eight blocks from the Lalaurie Mansion. A morbid parade of carnage moves down Royal Street, along Pirate Alley, to the gates of the prison at the Cabildo. There the victims are laid out in the same area where runaway slaves are whipped. The lashes and flails hang on the courtyard wall next to the groaning, bleeding slaves.

The Cabildo gate provided a safe haven for the unfortunate victims of the Lalauries. The victims were laid out inside of the courtyard, protected from the mobs trying to view them. Photo by Victoria Cosner Love.

The victims remain there for some hours, on display for all of New Orleans to see. More than four thousand people march grimly through the Cabildo to see the poor, wretched souls for themselves.

The huge mob outside the Lalaurie house, a mix of Creoles, black slaves, free people of color and Americans, has never seen anything so horrible. The people howl for the blood of the Lalauries.

Madame is only slightly concerned. She knows that Bastien will be bringing her carriage around for her evening ride momentarily. She can scarcely believe that the mob is so upset about the fate of a few worthless slaves. She smiles and shakes her pretty head in disbelief.

Exactly on time, Bastien arrives in the carriage. Madame steps lightly in and takes her seat, arranging her opulent gown just so. Bastien lashes the horses and begins to shove his way through the crowd.

Evening at St. John’s Bayou, circa 1903. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

Ugly, angry faces shout at her from every side. Madame smiles. Whether it is defiance, a lack of empathy or a display of impish and wildly inappropriate humor, she waves at the mob as the carriage gains speed. Soon the carriage is heading down the road to Bayou St. John, where Madame can hire a boat to take her across Lake Pontchartrain, until all of this silliness blows over.

Delphine does not know where her husband Louis is, though she is not concerned about this. Louis is intelligent and cunning. He will find his own way to escape the mob. And if he doesn’t, it won’t make much difference to her. He was by far her most entertaining spouse, but he is just a husband. He can be replaced. And her children are safe. Delphine arranged to have her daughters and young son taken out through the back of the house while the mob was distracted by her departure.

Madame’s carriage arrives at Bayou St. John. Loyal Bastien quickly finds a boat captain and pays him handsomely to take his mistress to the other side of the lake. Madame pats Bastien’s cheek fondly and boards the boat. As it paddles into the fog, she can hear the roar of the approaching mob and then the unmistakable shriek of horses in mortal agony. She is almost out of earshot when she hears Bastien begin to scream. She feels a pang for him, as if she has dropped and broken a pretty china music box.

At last the boat makes landing. Madame hires a carriage to take her to the home of a family friend. She is welcomed warmly, given food and drink and a comfortable bed. Sometime during the night, Louis Lalaurie arrives at the house with the children. He is terrified, convinced that the ravening mob will find them at any minute and rip them limb from limb. Madame laughs her tinkling giggle and tells him that he is a silly boy.

While at her friends’ house, Madame Lalaurie signs her power of attorney over to her trusted son-in-law. That way, if the ridiculous Americans attempt to press charges against her or seize her assets, she will be protected. Louis Lalaurie does the same.

Madame wonders, however briefly, about her Devil Baby, whom she has never bothered to name. Had he been incinerated in the fire? Had he been pulled from the house by the blood-crazed mob and torn to pieces? She feels wistful for a moment or two. She will miss his shrieks and delightful gibbering, as well as the way he could rip apart a live chicken with his sharp little baby teeth.

Back in New Orleans, after the fire has cooled and the house has been gutted, policemen stay on duty to make sure that no more damage is done to this once beautiful mansion. That very night, they begin to hear scratching and crying coming from somewhere in the house.

The officers and firemen search the devastated mansion for hidden rooms, following the footprint of the house. They search day after day, but no other victims are found. The horrible sounds continue for three weeks before they finally stop.

Rumors begin to circulate that the Lalaurie Mansion is haunted. The dead slaves are already coming back for revenge. The stories whip through the city, growing and changing, becoming more horrific with each whispered retelling. The legend of the most haunted house in America is born.

Madame and Louis Lalaurie know nothing of this. They book passage to Paris as soon as they are able. They have friends and family aplenty there, and they are welcomed with open arms.

From the moment they arrive, they don’t lack for food, lodging or fine company. Madame often tells the story of her slight misadventure in New Orleans and laughs about it. The hysterical, crude Americans had made a mountain out of a molehill. Imagine their nerve, chastising a highborn French Creole woman for merely disciplining her own domestics. Her friends and family laugh along with her.

Louis is another matter. He grows more nervous day by day. Much to Madame’s irritation, he seems to regret his magnificent and colorful medical experiments. He is becoming a bore, and she seeks the company of other, more interesting gentlemen. One day, Louis packs his trunks and leaves without a word. Madame doesn’t miss him in the least.

Her life continues on, one dazzling party after another, until the fateful day when a dreadful American preacher confronts her. He claims to have seen her at her home in New Orleans, torturing her slaves with her own lily-white hands.

Well, this is somewhat embarrassing. Her friends begin to ask her questions she does not care to answer. So Madame retreats to a distant relative’s home in Pau, out in the wild French countryside.

Madame Lalaurie enjoys her time there. For the first time in years, she can unleash her bloodlust, even if it is only on foxes and deer. She takes great satisfaction in watching her hounds rip a fox to pieces. It is almost as good as if she had done the deed herself.

Almost.

In December 1842, Madame Lalaurie accompanies her hosts on a hunt for wild boar. Everyone discouraged her from going. Boars can be dangerous, and hunting them is no job for a woman, they insisted. These arguments made Madame Lalaurie all the more keen to see the creature’s blood.

The thrill of hot pursuit is overwhelming. She and her horse are right behind the beast. She can smell its fear, and the primal adrenaline rush of blood sport makes her heart pound. Soon she will be close enough to shoot and then, if she is lucky, to plunge her knife into the still-living creature’s throat.

But her horse spooks and throws her. She lands hard in the bushes. Before she can catch her breath, the boar spins around and charges. She does not have time to scream before it splits her open from navel to neck. The last thing she sees is her own steaming intestines spilling out on the icy ground. She dies unrepentant, although her agony is overwhelming.

Madame’s body is secretly shipped back to New Orleans, as was her wish. She is quietly entombed in the St. Louis No. 1 cemetery in the middle of the night, and there she remains to this day, visited by family who keep the location of her tomb a closely guarded secret.

Do you believe that story?

The authors find it to be about as credible as the plot of any given Saw movie. (Lorelei’s note: This is not to say that I don’t love the Saw movies.)

If you want to know what conclusions we have drawn about the Lalaurie affair, turn the page, dear reader.