I am a-telling you I kept going from bad to worse, drinking more and more, and gambling whenever I had the chance or the money, and fighting a whole heap. I was never once whipped or knocked off my feet. I jes kinder thought I could whip the world and more than oncet I set out to do it. I was in a couple of shooting frays too.

—Alvin York

For Alvin York, growing up in the Cumberland Valley of Tennessee was little different from what the pioneers of the early 1700s experienced. It was a foreign place to most Americans, a land that time seemed to have forgotten. In many ways, York’s world was little changed from when Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett lived there. Legend reflected the Cumberland’s time-locked nature with its tales of Indian fighters and Civil War bushwhackers.1 Despite the innocent yarns spun about life in Appalachia, there was a dark side to it as well. In the shadows of the rough valleys, bootleggers, gun runners, and other men of ill repute made the region dangerous for the uninitiated. Adding to this was the fact that swathes of the region were largely outside the control of federal and state law. Alvin York would soon find himself lured into this dark world.

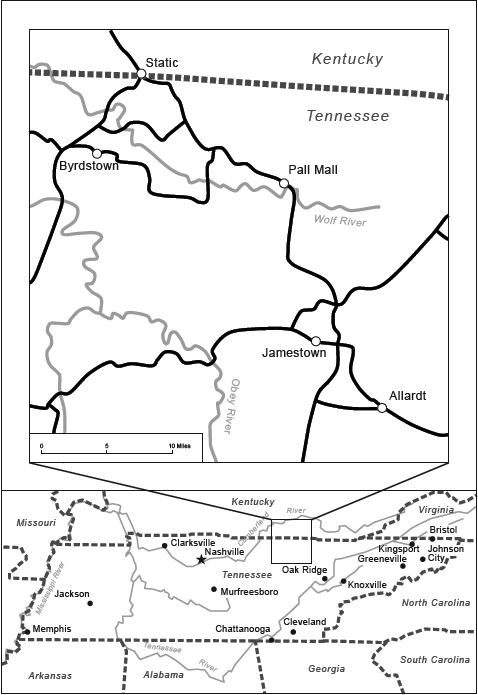

The third of eleven children, Alvin York was born on 13 December 1887 and grew up in a loving and hard-working home. His father, William York, and mother, Mary Brooks York, owned a small farm in Fentress County, near Pall Mall. This county was rural; the largest town of any consequence was the county seat of Jamestown, ten miles south of the York farm. York’s parents had a heavy burden with so many children. The entire York family worked to provide for one another. Life in the valley was hard. Living in a one-room cabin, Alvin was required to contribute to the family just as his siblings did. He helped his mother around the house as soon as he was old enough to do so, and was in the fields working the family’s seventy-five acres with his father before he was six years old.2 York wrote: “I begun to work almost as soon as I could walk. At first I would help Mother around the house, carrying water, getting a little stove wood, and carrying and nursing the other children to keep them from yelling around after Mother while she was trying to get a bite of dinner for us all. I would go out to the field with Father before I was six years old. I would have to chop the weeds out of the corn.”3

The rocky soil made growing corn difficult.4 Despite this, Alvin learned to raise crops, take care of farm animals, and work in the family blacksmith shop in the cave next to the cabin. Here he learned how to shod horses and mules.5 Yet, the most thrilling thing he learned from his father was hunting. Before he was old enough to join them, Alvin recalled being “red-eyed, by the gate of his home [as he] watched his father and the hounds go off to the hunt.”6 When that day finally arrived for him to join his father hunting, he displayed an unusual skill that caught his father’s attention.

It was during the long hunting trips in the mountains and fields around Pall Mall that Alvin was able to spend quality time with his father. The hunting was a way for the York family to put meat on the table and to make money on pelts. In such a large family, Alvin became a typical middle son, both quiet and resolute. It was difficult for him to stand out in the shadow of his two older brothers, Henry and Joe, or to distinguish himself from the half dozen younger siblings who needed their parents’ attention. During these hunting outings Alvin was able to observe his father’s Christian character and learn hunting skills.7 “But I most loved getting out with Father to help him shoot. We would hunt the red and gray foxes in the daytime and skunks, possums, and coons after dark. Often we would hunt all day and do the blacksmithing at night.”8

Alvin’s passion and talent for hunting created a personal bond between him and his father.9 In Alvin his father found a willing apprentice. At his father’s side, Alvin learned how to track animals, to read the weather, to train coon dogs, and to move unseen in the deep Tennessee woods.10 Shooting remained his passion, and he took every opportunity to perfect his skills with both handguns and rifles. Before long, Alvin matched his father’s skill in hunting raccoons, foxes, turkeys, wild hogs, and squirrels and had begun winning community turkey shoots.11 Alvin described the importance that this passion played in his relationship, saying, “It was sorter easy for me to talk [to his father] about guns and hounds and horses and all those things he loved and taught me to love.”12

York’s father was renowned across the region as a hunter and marksman. His expertise as a shooter was so great that often, in “beeve” (beef) shooting matches, when the best five shooters would divide a cow betwixt them, William York would win all five matches and bring the animal back alive and “on the hoof.”13 It was not just in beef shoots that William excelled, but in turkey shoots as well. In these matches, shooters would pay for each shot to kill a captured turkey. A live turkey was tied behind a log, with the shooters trying to hit the bird in the head from a distance of sixty yards. Such a crack shot was Alvin’s father that he was often placed at the bottom of the firing order. This gave the hosts a chance to raise more money by allowing other shooters a chance before William York hit the bird. Alvin admired his father’s skills and would take up his father’s rifle in a like manner.14 Little did he know that it was this love of his father’s shooting and hunting that was to prepare him for a dark day in France only a few years later.

The weapon of choice for the York family was the muzzle-loaded rifle. These long and unwieldy rifles were difficult to use, but when handled by a proficient rifleman were deadly accurate.15 Alvin also became an expert shot with a pistol. Finding his inspiration from tales of the bank robber Jesse James, Alvin recalled, “I used to practise and practise to shoot like them James boys. I used to get on my mule and gallop around and shoot from either hand and pump bullet after bullet in the same hole. I used to even throw the pistol from hand to hand and shoot jes as accurate. I could take that old pistol and knock off a lizard’s or a squirrel’s head from that far off that you could scarcely see it.”16

Religion, too, played a central role in eastern Tennessee and in shaping Alvin York’s character. Yet, this was not the Christianity of liturgy and tradition, but one of which the German Reformer Martin Luther advocated in 1517: “Sola Scriptura,” which is using only the Bible and not church doctrine as a guide for living.17 Although the region was largely influenced by Methodist theology, they welcomed itinerant Baptist and Church of Christ in Christian Union (CCCU) preachers due to the lack of ministers.18 Called “saddlebaggers” because of the large bags of Bibles, evangelical tracts, and hymnbooks they traveled with on their horses, these circuit preachers brought the Gospel to the mountain folk through revival meetings. The local population honored the Sabbath, and usually the only book any family owned and read was the Bible, so the preachers found a willing group to minister to. Daily family devotions with prayer and Bible reading were conducted by most folks in the region. Saying grace to give thanks to God for each meal was the norm as well, so that faith was expressed throughout the average day.19

Church services were important social events that every family in the area endeavored to attend, dressed in their “Sunday finest.”20 The church meetings included singing and a basic sermon on the need of an individual to confess and repent of his sins and turn his life over to the Lord and Savior Jesus Christ.21 These church events could last all day and included people bringing food to share in a sort of potluck fellowship. These were appropriately named “basket meetings.”22

The church in Pall Mall was unremarkable, having been built of wood planks by Methodists in the late 1800s. It was pleasantly situated in the valley near town. The interior was unpainted and lined with rough benches. The women sat to the right side of the church during services and the men to the left. The pulpit was slightly raised at the front of the church, with an altar, or “mourners’ bench,” just below it.23 As with most churches in the region, the one in Pall Mall was barren of symbols, icons, and illustrations. All that mattered was the Bible.

Public education, although available, was not practicable to the hard-working folks of Pall Mall and the Valley of the Three Forks of the Wolf River. Due to the time constraints imposed by a busy farming schedule, school was limited to the summer months, and often interrupted by the potato harvest, tomato harvest, etc.24 For Alvin, it was a good summer if he was able to squeeze in a month of school. By the time he entered adulthood, he had the equivalent of a third-grade education.25 As a result, the greatest influence on Alvin York was his parents: “Both my father and mother were honest, Godfearing people, and they did their best to bring us up that way. They didn’t drink, or swear, or smoke themselves, and they didn’t believe in us doing those things. They didn’t have no use nohow for people who told lies or broke promises. They believed in being straight out and aboveboard. I’m a-telling you they honoured the truth so much that they wouldn’t hide it nohow for nobody even if they was to suffer an awful lot.”26

Alvin grew up in a house filled with stability and acceptance. Behind it all, his father stood out as a man of integrity. William York was not just a Sunday Christian, but one who endeavored to live out his faith transparently, in humility and honesty. Whatever he put his hand to, he sought to “do it as unto God.” This applied to his work ethic and to his private life: “He was so fair and just in all relations with his neighbors that the people of the valley called him ‘Judge’ York; and his honesty was so rugged and impartial that not infrequently he was left as sole arbiter even when his own interests were involved.”27

The year 1911 was a turning point in the York household. By then, Alvin’s two older brothers, Henry and Joe, had their own farms and families, leaving York as the oldest son still living at home. William York was renowned throughout the region for his skill at shoeing horses and mules. One day in 1911 he was severely kicked by a mule, which triggered an illness from which he subsequently died.28

Almost overnight, Alvin went from being the overlooked middle child to the head of the household.29 This required him to run the seventy-five-acre farm and blacksmith shop and provide for his widowed mother and younger siblings.30 It seemed as if the weight of the world had fallen on him; indeed, it was a burden he was not ready for.31

Unfortunately for Alvin, temptation and escape from the stress of life were just a few miles north of Pall Mall, Tennessee, on the Kentucky state line, where plenty of moonshine was to be had.32 To avoid liquor laws, drinking establishments called “Blind Tigers” were built on the state border. Inside these “bars” the state line literally was painted across the floor.33 Whenever law enforcement officers turned up, the patrons and the booze moved to the Kentucky side of the saloon to avoid arrest.34

It should be no surprise that moonshine was the preferred liquor at the Blind Tigers, since Kentucky was the leading producer of it in the United States. The proximity of Kentucky to so many markets, in addition to plentiful grain and corn, made it a natural source for illegal booze. As the industry was not regulated, there was a danger of the whiskey being watered down or contaminated with lye, radiator fluid, or lead.35 Corn whiskey, which was locally called “John Barleycorn” or “Mountain Dew,” was a particularly potent drink.36 Some of the brew was 80–90 percent in alcohol content.37 One of the popular drinks was a corn-based sugar brew that resembles ethanol.38

The Blind Tigers drew a rough crowd and were places where one could gamble, meet women, fight, and most of all drink. Alvin wrote, “I am a-telling you Sodom and Gomorrah might have been bigger places, but they weren’t any worse. Killings were a-plenty. They used to say that they used to shoot fellows jes to see them kick. Knife fights and shooting were common, gambling and drinking were commoner, and lots of careless girls jes used to sorter drift in. It shore was tough.”39 One of the local establishments along the Kentucky-Tennessee border was operated by the Huddleson family. Twenty-five people were killed there in bar fights. The Huddlesons, York said, were “an ornery and right smart bad, tough lot of men. They wouldn’t do nothin’ downright dishonest, but they’d kill you at the drop of a hat.”40 Because of the violence at the Huddleson’s Blind Tiger and the poor nature of the moonshine that they served, York preferred another border dive called “Marter’s Place.”41

The trouble was that when York drank, he would get into fights. On occasions, he avoided fights by showing off his shooting skills. Once Alvin was with his usual group of friends and brothers and had a winning string of poker games. The losers were infuriated and pulled out their guns to settle the matter. To avoid a shootout, Alvin quickly pulled out a pistol and shot off the head of a lizard on a distant tree, saying, “If there’s going to be any shooting here I will do it.” That ended the argument.42

As with most men his age, Alvin’s path to self-destruction was slow. Particularly responsible for his moral decline was that Alvin was surrounded with companions who encouraged and enabled his downward slide. Describing his slip into perdition, Alvin wrote:

At the beginning we used to have a few drinks of a weekend and sit up nights, gambling our money away; and of course, like most of the others, I was always smoking and cussing. I don’t think I was mean and bad; I was jes kinder careless. But the habits grew stronger on me. Sorter like the water that runs down a hill at first it makes the ravine, and then the ravine takes control of the water that’s the way it was with me. I jes played with these things at first, and then they got a-hold of me and began to play with my life. I went from bad to worse. I began really to like liquor and gambling, and I was ’most always spoiling for a fight.43

Before Alvin knew it, his occasional drinks turned into weekend binges during which he would lose most of his money gambling “at poker, dice or some other game of chance.”44

Joining Alvin on his weekend jaunts to the Blind Tigers in the border settlements of Bald Rock and Static were his brothers Henry and Albert, and friends Marion Lephew, Everett Delk, and Marion Delk.45 “We were a wild crowd,” Alvin said, “wilder than wild bees when they’re swarming. On a week-end we would go across the Kentucky line and get drunk and look for trouble, and we shore enough found it.”46 Once armed with booze, Alvin and his companions would go on long drinking binges with hard Tennessee or Kentucky moonshine. In addition to shooting under each other’s mules, getting into fights, and gambling, the group found other ways to mix drunkenness with competition. One of Alvin’s favorite games was “last man standing.”47 The six men would drink as much as they could to see who would be the last not to pass out. Often the last two to stand were Alvin and Everett Delk, with Delk usually lasting the longest. The winner would take away all of the unconsumed liquor.48 On some weekends the group would purchase its whiskey at the Blind Tigers and then go to Jim Crabtree’s farm to consume it. Farmer Crabtree would join Alvin and his companions in a drink, and then his wife would feed them a large meal. After this, they would drink until they passed out.49

As expected, this behavior put York in trouble with the law. It started when he delivered a weapon for a friend and was subsequently arrested. York was called before a judge on charges of selling weapons across county lines, but he had the case dismissed after proving that it was not his rifle. Alvin’s next confrontation with the law occurred shortly after this, when he was returning from a weekend drinking binge in Kentucky. While riding on his mule intoxicated, Alvin spotted a flock of turkeys sitting on a fence. Alvin sluggishly pulled out his revolver and killed all six. But the birds belonged to a neighbor, and York was charged with a crime. Only by paying restitution was Alvin set free.50

On another occasion, in the same state of intoxication, Alvin and Everett spotted something white in the darkness. Everett thought that it was a “white pillow.” Not wanting to miss a chance to use his weapon at a distant target, Alvin fired. Upon closer inspection they were appalled to see that he had shot a neighbor’s pet goose. The guilty party fled the scene to avoid a court hearing.51 Alvin would often go into hiding after committing a crime, “until the excitement died down,” so as to avoid jail time.52

This pattern of behavior troubled his mother. Although Alvin was twenty-seven years old, his mother made a habit of waiting for him during his extended drinking binges. With violence being so common at the Blind Tigers, she was right to be concerned.53 Mrs. York, nevertheless, never assailed Alvin for his behavior, but tried to lovingly lead him back to the Lord’s way. As Alvin said: “Often she would remind me of my father, of how he never drunk, or gambled, or played around with bad company, and of how he would not like it nohow if he knowed what I was doing; and she used to meet me at the door and put her arms around me and tell me that I was not only wasting this life, but I was spoiling all my chances for the next. She used to say that she jes couldn’t bear to think of where I would go if I died or was killed while I was leading this wild life.”54

How far from his father’s counsel his life had drifted troubled Alvin, as he held his father in high esteem. Yet this was not enough to draw him to the straight and narrow. Mrs. York prayed for him and, with tears of despair, shared hope from the Bible with him.55 A passage that left an impression on Alvin was the parable of the Good Shepherd, which described a shepherd who left his flock of ninety-nine to find the one who strayed. Alvin knew that he was that lost sheep and was interested to hear the Savior’s desire to bring him back to the fold despite being stained with sin. This notwithstanding, the draw of alcohol was difficult to break, and he found himself in a moral conflict.56

All of this was making me feel kinder bad. I jes knowed I was wrong. I jes knowed there was no excuse for me. … When you get used to a thing, no matter how bad it is for you, it is most awful hard to give it up. It was a most awful struggle to me. I did a lot of walking through the mountains and thinking. I was fighting the thing inside of me and it was the worstest fight I ever had. I thought of my father and what a good man he was and how he expected me to grow up like him, and I sorter turned over in my mind all the sacrifices Mother had made for me.57

As Alvin York struggled with deciding what path in life he would follow, a lady caught his attention. The girl, Gracie Loretta Williams, lived near the York farm, just across a little stream called Butterfly Branch.58 Gracie’s quiet nature as well as her good looks appealed to Alvin. Alvin would often take the long way to the woods to hunt squirrels near her family’s farm, in the hopes of meeting with Gracie, who was often tending to the family’s cows nearby. Here they would have long conversations. Both looked forward to these “chance meetings.” But Gracie’s father, Francis “Frank” Asbury Williams, refused to allow the two to associate.59 As far as F. A. Williams was concerned, Alvin was too old for her and an unbeliever.60 Mr. Williams, a devoted Christian, felt Alvin was a drunkard and a gambler and unfit for any man’s daughter.61

F. A. Williams sought to live out his faith, and as such was a highly respected member of the community. His reputation for honesty was so impeccable that he served as a circuit judge. Williams believed that men were not born Christians, but had to choose to become so, just as Joshua proclaimed: “And if it seem evil unto you to serve the LORD, choose you this day whom ye will serve; whether the gods which your fathers served that were on the other side of the flood, or the gods of the Amorites, in whose land ye dwell: but as for me and my house, we will serve the LORD.”62 The most important concern for Mr. Williams was his family of thirteen children. To raise them in the understanding of the Lord, he led them in daily devotions, and endeavored to walk in God’s ways before them in word and deed. Of the decision to prohibit Gracie from seeing Alvin, Williams referred to 2 Corinthians 6:14: “Be ye not unequally yoked together with unbelievers: for what fellowship hath righteousness with unrighteousness? What communion hath light with darkness?”63

This prohibition did not pertain to chance meetings along the lane or in the pasture. But despite these work-arounds, there was no way York could romantically pursue Gracie.64 There had to be a way, as Alvin had found in Gracie something unusual. She was not naive, but virtuous in her Christian faith. Although she was shy around strangers, there was an inward strength that made her stand out.65 These were the traits that Alvin sought in a wife, as she was in every manner opposite to the girls he met at the Blind Tigers.66 Alvin could only publicly see Gracie at church. With this incentive, he became more interested in attending, for the sake of speaking to her and walking home with her family after service.67 As Alvin was a “backslider,” these were often awkward encounters. The bottom line was that as long as he was not a practicing Christian, she would never concede to marrying.68

Alvin was torn between the choices before him. For now, the easiest thing was to continue along the path of least resistance—that is, feeding his earthly desires. The weekend forays to the Bald Rock and Static Blind Tigers continued, as did his efforts to avoid arrest for various infractions of the law.69 But Alvin began to struggle in prayer and doubt. His daylong hunting excursions gave him time to wrestle with the direction of his life. There was a deep emptiness from the choices he had made. Alvin knew that he would end up dead soon if things did not change. A nagging guilt haunted him about the path that his parents had laid out for him, and there was Gracie, who was only interested in a Christian man.70

During the period leading up to New Year’s Day 1915, the Pall Mall church hosted a weeklong revival service led by Reverend Melvin Herbert Russell of Indiana.71 Reverend Russell was a saddlebag preacher bringing the Gospel across Indiana, Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee. His years of experience preaching the Gospel in the region, and years of studying the Bible, made him well suited to reach the locals.72 Alvin was invited to attend and did not need much urging, as he wanted to see Gracie.73

Alvin attended most of the revival meetings that week, with the meeting house being packed full. Russell’s preaching was straight from the Bible, and he did not mince words. Alvin described the preacher as being like one of the Apostles of old, speaking God’s words with an urgency borne of the conviction that “now is the time of salvation,” for we are all sinners doomed to hell unless we repent and call upon the Savior.74

Alvin watched scores of his neighbors and friends go forward to the “mourners’ bench” to repent of their sins and accept Jesus as Lord and Savior at the end of each service. Although the sermons moved him, and what Reverend Russell preached made sense, it was not enough to cause Alvin to join the penitent. Nonetheless, he felt a power behind what Russell preached.75 If he was to follow the Lord, he knew he would have to do it for himself, not for his mother, or for his father’s sake, or even Gracie’s. During that week he experienced soul-felt conviction, causing him to contemplate life: “Sometimes I used to walk out on the mountainside and do a heap of thinking and praying before the meetings. Then I would go and listen and pray and ask God to forgive me for my sins and help me to see the light. And He did.”76

Alvin’s life-changing decision occurred on New Year’s Day 1915. During the last night of the revival service, he listened to Reverend Russell preach that “the wages of sin is death; but the gift of God is eternal life through Jesus Christ our Lord.”77 At that moment it all made perfect sense to him. York would later say that the Gospel message was so clear to him at that moment that “it was as if lightning struck my soul.”78 He saw the sin in his life for what it was, a death sentence, and also understood his need for the Savior. When the invitation was given by Reverend Russell, a neighbor, Sam Williams, saw York getting ready to go forward to accept the Lord. Sam Williams had hired Alvin to work around his farm for several years and was concerned about the path the young man was on. Sam too stood up, put his arm around Alvin, and walked with him to the mourners’ bench at the front of the church.79 Reverend Russell led the penitent in a prayer of repentance and then welcomed Alvin heartily into the family of God. Alvin stood up a changed man.80