7

One Day in October

The concept of American operations for 8 October 1918 was to launch a three-prong attack into the Argonne, with York’s battalion advancing in the center while the 1st Battalion pushed from its position on Castle Hill to the right.1 The 3rd battalion would serve in reserve, and the nearby 28th Division would attack just south of the 82nd. The 328th Regiment’s attack was part of a larger assault that day, which included the 110th Infantry Regiment of the 28th U.S. Division providing a supporting attack to seize the high ground on the left, while another regiment of the 82nd Division, the 327th, would attack on the right, toward the village of Cornay.2 The time of the attack that would propel Alvin York to renown was changed from 5:00 A.M. to 6:00 A.M., to give artillery, as well as the men, a chance to be in place. The attack would be preceded by a ten-minute artillery barrage, with the men stepping off immediately after that at 6:10 A.M. Understanding that its sister battalion had had a terrible battle there on 7 October fighting for Hill 223, York’s unit was reinforced with a machine gun company and a one-pounder mortar platoon. A company of fifteen American-manned French light tanks was also available to support the attack if needed. Unfortunately, the terrain was not suitable for the tanks to operate.3

York and his battalion attempted to sleep on the drenched, muddy ground near the Aire River, only getting wetter and dirtier as heavy rain fell on them through the night. At 3:00 A.M., Captain Danforth and Lieutenant Stewart organized the men to begin their movement to Châtel Chéhéry.4 According to the plan, York’s battalion would pass through the remnant of the Americans holding Hill 223 and then wait for the moment to attack.5 Most of the bridges of the Aire River had been destroyed by the Germans, so American engineers laid narrow boards for the crossing. Despite the darkness, this was accomplished without incident. Once across the river, the battalion reformed and began the steep half-mile hike up to the village of Châtel Chéhéry.6

York passed through the village of Châtel Chéhéry early in the morning on 8 October 1918 just before participating in a bloody attack against German defensive lines. The village, nestled against the dense Argonne Forest, was untouched for most of the war and was used by German soldiers between 1914 and 1918 as a rest area. By the time that York’s regiment arrived, the town had suffered damage from American artillery. (AHEC)

Although there was a fog in the Meuse Valley the morning of 8 October, the day promised to be clear and sunny, giving the Germans excellent observation. As the Americans made the climb to the village, German lookouts on the edge of the Argonne saw them.7 Within moments, enemy artillery harassed the 328th Regiment’s movement to its jump-off line. This included poisonous gas, which further slowed the formation, as they had to stop to don their masks and then move through the darkness with them on. One of the German artillery rounds exploded in the midst of the column, killing an entire squad.8 York reflected on this: “They done laid down the meanest kind of a barrage too, and the air was jes full of gas. But we put on our masks and kept plugging and slipping and sliding, or falling into holes and tripping over all sorts of things and getting up again and stumbling on for a few yards and then going down again, until we done reached the hill.”9

York remembered this movement to Hill 223 as slow and chaotic. There was no quiet in the Meuse Valley. Rather, it was alive with the movement of tens of thousands of men, trucks, and horses, mingled with the terrific explosions of artillery and the splattering of machine gun fires. The men constantly slipped and fell onto the muddy ground and easily lost their way in the darkness despite the frequent bright flashes. Of this, York says, “We were marching, I might say floundering around, in column of squads. The noise were worse than ever, and everybody was shouting through the dark, and nobody seemed to be able to hear what anybody else said.”10

Just as twilight was breaking, the men made it to Hill 223, much to the relief of the survivors who had held the hill against incredible odds since the previous day. One of the units that York’s men relieved was “B” Company, which had lost sixty-three men.11 As the men of the 2nd Battalion waited for the order to attack, they all knew that this would be a vicious fight. On the brink of entering the abyss of a violent battle, their thoughts were on everything from home to loved ones. For Private Mario Muzzi, it was his thirtieth birthday. His gift would be his life. He would be the sole survivor of his squad, with the rest being killed in only a few hours.12

In York’s platoon was Corporal Cutting. York and Cutting had never overcome their antipathy. Cutting distrusted York and wondered if he would do his duty and kill Germans. As York led the squad on the left of the attack formation, Cutting wondered, “Would he run and leave us exposed?”13 Yet, Cutting was troubled by even greater matters. Since he had lied about his name to join the army, he wondered how his mother would ever know of his death. His entire service record was a fabrication, with a false name, a fictitious hometown, and an invented career listed on it. There were no clues that Cutting was really Otis B. Merrithew.14 Fearing that he would be kicked out of the army for perjury if he told the truth, he never uttered a word of this, not even to his friend Bernie Early.15 As “Cutting” was about to come clean about this to Early, it was time to “go over the top,” and the secret went with him into battle and nearly into the grave.16

As the Americans waited for the order to attack, the Germans were making final preparations to repulse them from the Argonne entirely. The German battalion commander, Leutnant Paul Vollmer, only a mile across the valley from the Americans, had a mix of good and bad reports that morning. Organizing his defense from a small wooden hut in the meadow below Humserberg, he still had concerns about gaps on his right flank. Adding to this anxiety was that his adjutant, Leutnant Bayer, was being treated by medics as the result of being gassed near Apremont the previous day. Vollmer directed Leutnant Karl Glass to serve as the acting adjutant until Bayer returned, leaving one less officer in the line.17

But things started to look up after the Bavarian 7th Mineur (Sapper) Company, under Leutnant Max Thoma, arrived with a lead detachment of men from the 210th Prussian Reserve Regiment. Vollmer expertly placed the two units in the gaps on Hill 2 that Kübler and Endriss complained about previously. The Bavarian lieutenant, Max Thoma, was satisfied with his position and he colocated with the machine guns of Vollmer’s 2nd Company, which had excellent fields of fire up the valley. All of the gaps in Vollmer’s line were now sealed, and his men were ready to make this a bloody day for the Americans.18

As the hour struck, things started to go terribly wrong for the Americans. The American infantry units were ready to attack and waited for the explosions of supporting artillery to blast a way through the Germans. The barrage, however, never materialized. As the time ticked away toward the 6:10 A.M. assault, the officers had a quick meeting, with Captain Tillman deciding that the men would go over with or without the barrage. Tillman ordered the light mortar platoon and the machine gun company supporting his unit to open fire with everything they had.19 Although making a lot of noise, these did nothing to the German defenders, who were safe in their positions.20

At precisely 6:10 A.M., the officers of 2nd Battalion, 328th Infantry Regiment, blew their whistles and ordered the men to attack. As there were few trenches on Hill 223, the men were largely crouching or sitting on the back slope of the hill jutting above Châtel Chéhéry. The large American battalion attacked into the valley in two waves, with two companies in each wave moving parallel.21 A hundred yards separated the waves. York’s unit was in the second half of the lead attacking company, on the left. Immediately they crashed into the remnants of Battalion Müller hidden along the low western slope of Castle Hill.22 York noted of these defenders, “And there were some snipers and German machine guns left there hidden in the brush and in fox holes. And they sniped at us a whole heap. I guess we must have run over the top of some of them, too, because a little later on we were getting fire from the rear.”23 Battalion Müller held on until its 1st Company, 47th MG Sharpshooters, ran out of ammunition. After this, the Germans here retreated across the valley to the lines of the 125th Regiment.

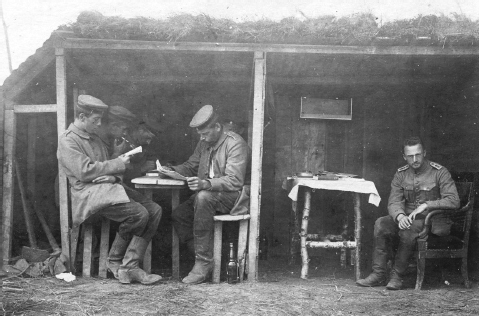

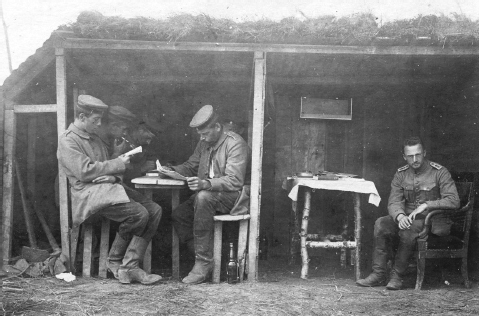

York’s nemesis was Leutnant Paul Vollmer. After four years of combat experience, Vollmer had demonstrated that he was a reliable and hard fighting officer. Vollmer set up his battalion headquarters in a small shack similar to the one in this photograph along the eastern edge of the Argonne Forest. York would capture Vollmer near his headquarters on the morning of 8 October 1918. (NARA)

With Battalion Müller out of the way, the Americans cleared Hill 223 and plunged into the valley. The Americans could not but be disheartened by the terrain that was now before them. As they came out of the woods behind Hill 223, the battalion entered a clear and steep valley about a half-mile wide. This dead space was devoid of trees, with the ground sloped down to a narrow stream and from there jutting up sharply to the large, heavily forested hills of the ancient Argonne Forest. The soldiers knew that the ground favored the German defenders greatly, and this notion was made clear when the Germans opened fire on them from the north, south, and west.24 York described the terrible situation that they faced:

Things were far worse than any of the Americans realized. Not only were the Germans well positioned to defend here, but Major Tillman’s battalion was attacking alone, with no support on either its left or right flanks. The Pennsylvanians, who were to advance on the left flank, had hit tough German resistance and were unable to advance.26

Due to a last-minute change in the plan, Tillman’s battalion was also attacking in the wrong direction. Corps headquarters had changed the unit’s attack plan and objective early on the morning of 8 October. Instead of attacking in a northwesterly direction to sever the German supply road in the Argonne, York’s unit was supposed to attack due west, so as to have the protection of the Pennsylvanians on the left flank. But the runner delivering the message to Major Tillman was killed just below Hill 223 and the order never arrived. The 82nd unit attacking on the right flank did receive the order, although only after it had attacked.27 Having the new plan of attack, the supporting unit on the right flank of York’s battalion swung away to the north, leaving York’s battalion on its own, with both its right and left flanks “in the air.”28

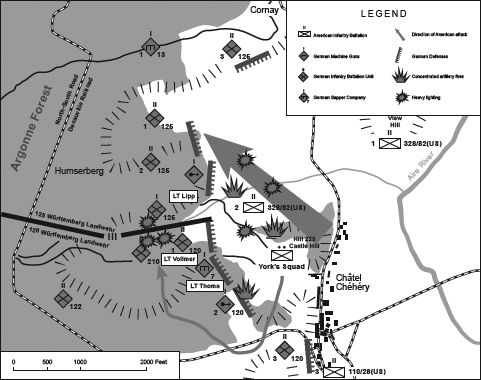

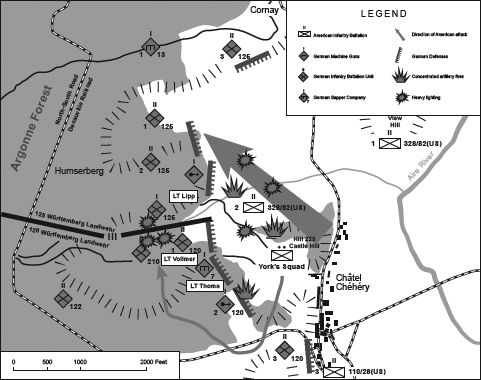

Map 6. York’s unit attacks into the Argonne Forest, 8 October 1918.

Leading the attack in front of York was his platoon leader, Lieutenant Kirby Stewart, holding his Colt pistol high in the air as he waved them forward. As Lieutenant Stewart and his men reached the center of the open valley, a burst of machine gun fire from the center hill cut the lieutenant down, throwing him about like a rag doll. His legs were shattered by a blast of German machine gun bullets. With every attempt to get up, he crumpled into a heap. With incredible bravery Stewart continued forward, dragging himself on the ground and every few seconds waving his pistol in the air and yelling to encourage his men. Before the platoon could reach the lieutenant, another German bullet hit him in the head, killing him instantly.29 Command of the platoon now went to Sergeant Parsons.30

By now, the attack was stopped in the middle of the valley, with the men facing in a northwesterly direction. Now began the impossible task of digging into indefensible ground. Sergeant Parsons tried to get orders from Captain Danforth, but could not. Captain Danforth was farther to the right, leading the preponderance of the company in trying to get around the northeastern portion of Humserberg, the hill in the center of the valley. The burden of command in the middle fell to Parsons. He moved about checking his men and surmised the situation.31

As the Americans had attacked to the northwest, the left flank was being racked by German machine guns from the large hill in the center of the valley. Seeing this, Parsons saw that the center hill that the Germans often referred to Humserberg was his biggest problem and that the machine guns on that specific hill had to be taken out. In this he was absolutely correct, as a large group of soldiers from the German 125th Landwehr Württemberg Regiment and a company from the 5th Prussian Guards were positioned there and had excellent lines of sight into the American flank. One of the German company commanders stationed on this center hill was Leutnant Paul Lipp, who would play a key part in the York story.32 Parsons ordered Early, Cutting, York, and Savage to lead their squads to take out the German machine guns on the center hill.33

Corporal Early was serving as acting sergeant and was in charge of these four squads, with Cutting, York, and Savage being his other noncommissioned officers.34 Two men from this element had already fallen in combat, leaving seventeen soldiers to make the flank attack that would decide the outcome of the day’s battle. The platoon included Bernard Early, Corporal York, Corporal Savage, Corporal Cutting, and Privates Maryan Dymowsky, Carl Swansen, Fred Wareing, Ralph Wiler, Mario Muzzi, William Wine, Percy Beardsley, Patrick Donohue, Thomas Johnson, Joseph Kornacki, Michael Sacina, Feodor Sok, and George Wills. Early surveyed the ground as the squad leaders gathered their men in the midst of German artillery that was now falling upon them.35 Directly south, Early saw a deep, natural notch cut into the ridge and determined that this was the best place to attempt the flanking maneuver.36

However, moving the men in a parallel direction under German machine gunners across exposed ground would be difficult—if not impossible—to accomplish. As the group of seventeen began their sprint for the southern hill, suddenly a barrage of artillery erupted near them. It was the belated American artillery support, and at that moment it was actually rolling across the southern ridgeline where the seventeen Americans were attempting to move. This artillery fire was exploding upon the German 2nd Württemberg Machine Gun Company, which was deployed there. The timing of the barrage caused the German gunners to seek cover just at the moment when the seventeen Americans were in their sights. Because of this, all seventeen of the Americans made it up the hill unseen and unhurt.37

A 75 mm gun of the 108th Field Artillery fires against German positions near Châtel Chéhéry to support the attack of York’s 82nd Division in October 1918. (NARA)

Bernie Early led the group in good order up the hill and into the forest. For the men, it was a relief to be out of the death trap of a valley. Early next turned the men west so that they could move into the Argonne Forest. This would enable them to move behind and around the flank of the German machine guns on the center hill that were holding up the attack in the valley. An hour elapsed during this movement. The men advanced slowly to ensure that they would not be discovered by Germans.38

Early’s platoon continued moving behind the German lines for some five hundred yards, then stopped so he could confer with York, Cutting, and Savage. Early thought they needed to go farther before turning the German flank, but he wanted to see what his leaders thought. Savage and Cutting thought they had gone far enough, while York suggested that they move a bit farther west before attacking into the German flank. Early went with York’s recommendation and continued moving. After a few minutes the seventeen Americans came across a shallow trench cutting across the northern face of the ridge. Early held another leaders’ conference and asked York, Savage, and Cutting what they thought—continue west into the forest or turn the German flank. This time the consensus was to turn the flank by moving down this trench. The trench was about three feet deep and was great a way to reduce their vulnerability to observation.39

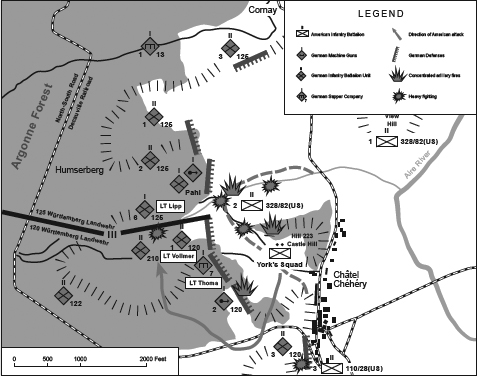

Map 7. York’s unit is stopped in the Argonne, and York and sixteen other soldiers maneuver into the German flank.

The trench was actually not part of the German defenses. It was a border line between private and communal land, dug in the seventeenth century.40 As it was not constructed for military purposes, it was a straight trench, carved into the northern face of the southern ridgeline that overlooked the valley from which these Americans had come.41 The trench ended near the base of the hill, facing north, and just above a supply road that the Germans had carved into the Argonne Forest. The Americans followed the supply road for a short distance to the west, where they came upon a small stream. Bending over the stream were two German sanitation soldiers, with Red Cross armbands, filling canteens. Leutnant Vollmer had sent these men a few minutes earlier from his headquarters to retrieve water for the men.42

The Germans froze momentarily in disbelief. When they saw the Americans surge toward them, the two dropped their water bottles, which made a series of loud, hollow metallic clangs, and ran for their lives. The Germans ran northeast, across a dense meadow, headed straight back to Vollmer’s headquarters to alert the commander to the presence of the Americans. The Germans ran as fast as they could, with the Americans hot on their trail.43 York recollected:

Meanwhile, Leutnant Vollmer had moved forward with his battalion to bolster the 2nd Machine Gun and 7th Bavarian Companies, which bore the brunt of the American attack. After weeks of setbacks, it looked like at last the Germans would take the initiative in the Argonne. Although the barrage caused considerable German casualties on Hill 2, Vollmer, acting on his own initiative, directed Leutnant Endriss to send a platoon to plug the gaps on Hill 2 so as to shore up the area from American penetration.45

Vollmer adjusted his battalion to block an American advance up the valley and retained control of the situation, with the Americans suffering heavy casualties. As the Germans reported, “Without any artillery preparation, the adversary launched a violent attack and there was heavy fighting, which lasted well into the evening. The enemy was repulsed almost everywhere. [The 120th Württemberg’s] 1st battalion [led by Vollmer] absorbed the brunt of the enemy attack without wavering, due to its good defensive position.”46

Vollmer was busy directing his battalion against the Americans when his adjutant, Lieutenant Glass, approached. Vollmer was relieved to hear that two companies of the Prussian 210th Reserve Infantry Regiment had just arrived at the battalion command post and were waiting for his orders.47 The 210th was the force that Vollmer needed to launch the much-anticipated counterattack to push the Americans out of the eastern portion of the Argonne Forest. This would defeat the American attack, save the day for the Germans in the Argonne, and expose the flank of the main American attack in the Meuse Valley.48

Vollmer told Glass to join him in meeting the senior 210th Prussian soldier on-site. They needed to be ready for the counterattack no later than 10:30 A.M. There was no time to waste if the attack would be launched on time. The 210th was only a few hundred feet up the valley, near Vollmer’s humble battalion command post. Vollmer’s headquarters had its usual number of orderlies, stretcher bearers, and runners standing around the shabby wooden shack awaiting orders. However, it was the Prussians that concerned him.49

Vollmer was appalled at what he saw. About seventy soldiers of the 210th had laid down their arms and were eating breakfast. The Prussians had loaves of bread, marmalade, and canned meat out and were in no hurry to do anything.50 Leutnants Vollmer and Glass rebuffed the 210th for their lack of preparedness and carelessness. Vollmer reminded them that there was a fight going on and that he needed them. The weary men of the 210th were unmoved by Vollmer’s appeals and merely replied: “We hiked all night and first of all we need something to eat.” Indeed, these soldiers had moved from the Meuse Valley, through the night, and frequently under artillery fire. They were tired and hungry. Frustrated by this lack of energy, Vollmer told Glass to go back to the front and then turned to order the Prussians to move quickly. Vollmer’s responsibilities were divided between the ongoing battle and organizing his taskforce for the 10:30 A.M. counterattack. He was about to wheel around to make a report to his regimental commander, Major Ziegler, but something was moving across the meadow.51

Suddenly, bursting from the foliage of the meadow came the two soldiers that Vollmer had sent to fill canteens, yelling, “Die Amerikaner kommen!” Off to the right, Vollmer noticed a group of 210th soldiers dropping their weapons and belts, yelling “Kamerad” with their hands in the air. Not knowing what was going on, Vollmer threateningly drew his pistol and yelled to them to pick up their weapons and arm themselves.52 Just out of Vollmer’s vision, to his rear, the Prussians had reacted to what looked like a large group of Americans charging across the meadow.53 Believing it was an American penetration of some one hundred troops, or perhaps American shock troops, the soldiers of the 210th were caught by surprise and surrendered. Before Vollmer realized what had happened, a “large and strong American man with a red-mustache, broad features and a freckle face” captured him. It was Corporal Alvin C. York.54

Meanwhile, Leutnant Glass, whom Vollmer had just moments before sent back to the front, returned to the command post to report that he had seen American troops moving near the meadow. Before he realized it, Glass too was a prisoner. Everything occurred so quickly that both Vollmer and the 210th Regiment’s soldiers believed that this was a larger surprise attack launched by the Americans, not just a patrol of seventeen soldiers.55

Bernie Early ordered his men to quickly search the seventy prisoners, line them up, and get ready to move. It was a chaotic situation. Around the seventeen Americans there were the sounds of war—from the valley to the east and the hills in front and behind them—as German gunners fired upon their brothers at arms in the death trap less than half a mile away. While the Americans were busy getting the prisoners in order, the 4th and 6th Companies of the 125th Württemberg Landwehr Regiment on Humserberg, the hill just above the American patrol, realized that there was trouble below.56

A crew of German machine gunners under the command of Leutnant Paul Lipp were directly above Vollmer’s headquarters and had been firing to the east, into the diminishing ranks of the besieged American battalion.57 On seeing the capture of their countrymen below, the machine gun’s crewmen yelled and signaled to the captured Germans to lie down. As soon as that happened, the Württembergers opened fire. The hail of bullets killed six of the seventeen Americans and wounded three more.58 The situation was so chaotic that several Germans were also killed by the machine gun fire.59 With that, the German POWs started waving their hands wildly in the air, yelling, “Don’t shoot, there are Germans here!”60 German leutnant Paul Adolf August Lipp, the commander of 6th Company, 125th Regiment, steadied his men and had them aim more carefully, looking for the distinctive British-style helmets worn by the Americans. Lipp then went off to bring up riflemen to join the machine gunners and help Vollmer out of his predicament.61

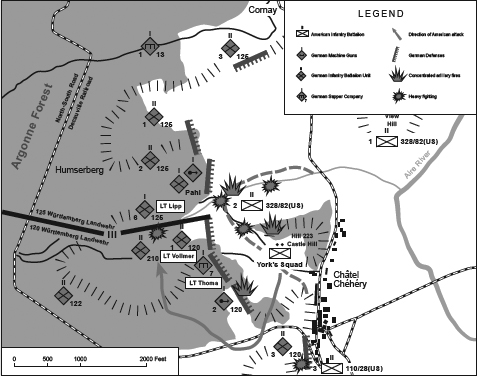

Map 8. York’s 8 October 1918 battle.

The situation for York and the other Americans was not promising. Six of the seventeen Americans were killed (Corporal Murray Savage and Privates Maryan Dymowsky, Carl Swansen, Fred Wareing, Ralph Wiler, and William Wine), while three others were wounded (Acting Sergeant Bernard Early, Corporal William Cutting, and Private Mario Muzzi). The remaining eight soldiers still able to fight included Corporal Alvin York (the only NCO left standing) and Privates Percy Beardsley, Patrick Donohue, Thomas Johnson, Joseph Kornacki, Michael Sacina, Feodor Sok, and George Wills.62

The survivors were scattered across the meadow floor, lying on or near their German prisoners, who were also sprawled on the ground trying not to get shot. The German machine gun above them fired at anything that moved. The Americans shouted to each other to ascertain who was injured. Bernie Early was severely injured by five bullets that had ripped into his body, while Cutting was incapacitated after being shot by three bullets that tore up his arm, and Mario Muzzi was shot in the shoulder.63 The worst was Corporal Murray Savage, York’s close friend, who was shot to pieces. His body and clothes were spread across the meadow in a heap of bloody shreds. York was shocked and dismayed to see the remains of the person he most cared about in the army.64

Whatever misgivings York had about fighting vanished upon seeing the death of Savage. Being the only noncommissioned officer not dead or wounded, and with the burden of command now upon him, York determined to stop the killing.65 After taking a quick analysis of the situation, Alvin seized the initiative. According to the account on his Congressional Medal of Honor citation, “He charged with great daring a machine gun nest which was pouring deadly and incessant fire upon his platoon.”66 The seven other American survivors provided covering fires for Alvin anytime he moved, with Beardsley shooting his Chauchat in support.67 Most of the American survivors said that the positions that they ended up in after the German machine gun opened fire prevented them from doing much to aid Alvin’s assault other than keeping watch over the prisoners.68

One of York’s men, Private Percy Beardsley, carried the notoriously unreliable Chauchat light machine gun into battle on 8 October 1918. This weapon had a propensity to jam in the midst of a fight. When this occurred, the gunner often had to resort to using his sidearm. Ballistic forensic analysis demonstrates that Beardsley did just that on the morning of 8 October. (NARA)

German soldiers man the MG 08/15, Germany’s premier machine gun of World War I. The Germans had mastered the integration of the machine gun with deadly effect during the First World War, killing many of York’s platoonmates. It was this type of machine gun that York charged, killing its crew, on 8 October 1918. (NARA)

To eliminate the machine gun that was causing so much death, York charged partly up Humserberg and crossed a German supply road that was about 160 yards above the meadow.69 He took a prone shooting position just above this road. What York saw about fifty yards to the west were groups of German soldiers occupying two sunken roads that ran above and parallel with the supply road he had just crossed. York’s position was the tip of a “V” where the two ancient sunken roads converged. From here Alvin had clear lines of sight up both roads and opened fire,70 killing the machine gun crew and its supporting riflemen, a total of nineteen Germans.71 He had fired nearly all of the rifle bullets from his front belt pouches in this engagement, some forty-six rounds.72 In an unusual coolness of mind, he frequently yelled to the Germans to surrender so that he would not kill more than he had to. His squadmates could hear him demanding their surrender in the meadow below. In spite of this, the Germans were oblivious to his presence and perished as a result.73 As York contemplated what to do next, Leutnant Lipp was arriving from farther up the hill with more riflemen. Taking advantage of the lull, York wheeled about to make his way back to the meadow to his men and the prisoners.74

As York came down the hill, he passed behind the border trench occupied by Leutnant Fritz Endriss and part of his platoon. Endriss saw York running down the hill and ordered his men to prepare for a bayonet attack. With bayonets fixed and ready, Endriss led the attack and charged out of the trench toward York. Twelve soldiers followed dutifully, but they had no idea against whom they were charging.75 As far as they were concerned, the battle was to the east, not the west. But they nonetheless followed Endriss.76

Seeing this, York slid on his side, dropped his rifle, and pulled out his M1911 Automatic Colt Pistol (ACP). Each magazine in this weapon held seven rounds. York stopped adjacent to Private Beardsley, who also had his own .45 ACP and fired in support of York against the bayonet attack. York used a hunting skill he had learned when faced with a flock of turkeys. He picked off the advancing foes from back to front. The logic behind this was that if the lead Germans fell, the trailing Germans would seek cover and be all the more difficult to kill. As Germans fell, several of the other attackers broke off and headed back to the trench. By now, half of the charging soldiers were dead. Right next to York, and unbeknownst to him, Private Beardsley was also firing into the German throng. Between the two, there was no way that this bayonet attack would succeed. During the fracas a nearby German threw a hand grenade at York and Beardsley, which exploded behind them in the meadow, wounding several German prisoners.77

With his platoon either dead or back in the trench, Endriss was now charging alone. The last attacking German now only a few feet away, York fired, throwing Endriss back as the .45 bullet slammed into his body. He was hit in the abdomen, writhing and screaming in agony less than ten feet from York. This event occurred in clear view of Leutnant Vollmer, who was still lying on the meadow as a prisoner. There were now twenty-five dead Germans across the side of the hill.78

Much as York mourned the loss of Savage, now Vollmer wanted to save his friend Endriss. In the midst of the fight, Vollmer stood up and walked over to Alvin and yelled above the din of battle in English (he had lived in Chicago before the war), “English?”

York replied: “No, not English.”

Vollmer: “What?”

York: “American.”

Vollmer: “Good Lord! If you won’t shoot any more I will make them give up.”79

York told him to do it, and pointed his pistol at him as a warning against any trickery. Vollmer blew a whistle and yelled an order. Leutnant Lipp was in charge of the 125th Regiment’s troops on this part of the hill. He was not sure what was going on, but he had lost a lot of men and he knew and trusted Vollmer. Hearing Vollmer’s order, Lipp told his men to drop their weapons and to make their way down the hill to join the other prisoners, who were under the charge of only eight Americans.80

York used Vollmer to translate orders to the one hundred or so prisoners.81 As they were readying for the return trip to the American lines, York’s men expressed concern about whether they could handle so many prisoners. Hearing this, Vollmer realized that there were not many Americans after all and asked how many men York had, to which York replied, “I have plenty.” York ordered Vollmer to quickly line the Germans in a column of twos and tell them to carry out the wounded Americans and Germans, which included Vollmer’s dying friend, Leutnant Endriss, and Corporal Cutting.82 Alvin then checked on the wounded Americans, seeing first Bernie Early, who said, “York, I’m shot and shot bad. What’ll I do?” Seeing he needed help moving, Alvin answered, “You can come out in rear of the column with the other boys.” With that, fellow Irishman Private “Patty” Donohue and several of the German prisoners assisted Early, Cutting, and Muzzi to the back of the formation to get out of the Argonne.83

York took the German officers (Lipp and Vollmer) and placed them at the head of the formation, with Vollmer at the lead. Another officer, Leutnant Glass, had an overcoat on and was not observed as being an officer. York stood directly behind Vollmer, with a .45 Colt semiautomatic pistol pointed at his back, and had to decide which route to take back to the lines. Retracing their steps up into the hills would be suicide, as there would be no way that they could control this large group of prisoners in that difficult terrain. Vollmer suggested that York take the men down a gully in front of Humserberg off to the left, which was occupied by a large group of German soldiers. Sensing that this was a trap, York balked at the idea and took them instead down the road that skirted the ridgeline to the south. This was the same road Early had led the men across when they spotted the first two Germans with the canteens. It was a good choice, as it led back to Hill 223 and Châtel Chéhéry, and it was the only route by which he could have safely moved the prisoners.84

Meanwhile, slightly forward of York’s position was another of Vollmer’s officers, Leutnant Kübler, and his platoon. Kübler realized that it was too quiet behind the lines and to his left and told his second in command, Sergeant Major Haegele, “things just don’t look right.” Kübler ordered his men to grab their weapons and follow him to the battalion command post. As they approached, he and his men were immediately surrounded by several of York’s men. Kübler and his platoon surrendered and joined the prisoners. Vollmer used the opportunity to alert nearby troops by loudly ordering Kübler’s men to drop their weapons and equipment belts.85

Leutnant Thoma, the commander of the Bavarian 7th Mineur Company, heard Vollmer’s order to Kübler. He turned and saw several of York’s men moving up the road. Thoma ordered his men to follow him with their bayonets fixed and ran in the direction of York and the one hundred–plus German prisoners, yelling, “Don’t take off your belts!” Thoma’s men took a position near the road for a fight. York shoved his pistol in Vollmer’s back and demanded that he order Thoma to surrender. The following exchange occurred:

Vollmer: “You must surrender!”

Thoma: “I will not let them capture me.”

Vollmer: “It is useless, we are surrounded.”

Thoma: “I will do so on your responsibility!”

Vollmer: “I take all responsibility.”86

Thoma and his men, with elements of the 2nd Machine Gun Company, surrendered.87 They dropped their weapons and belts and joined the large formation of prisoners.88 As they crossed the valley, the battalion adjutant of York’s unit, Lieutenant Joseph A. Woods, saw the formation from Hill 223 and believed that it was a German counterattack. Woods gathered as many scouts and runners as he could to fight off this potential threat. But after a closer look he realized that the Germans were unarmed and noticed Alvin York at the head of the formation, just behind Vollmer. At Hill 223, York saluted and said, “Company G reports with prisoners sir.”89 Lieutenant Woods answered, “How many prisoners have you corporal?” York replied, “Honest lieutenant, I don’t know.” Woods answered, “Take them back to Châtel Chéhéry and I will count them as they go by.”90 He counted 132 German soldiers, with the battalion commander, Major Tillman, present as an eyewitness. Lieutenant Woods noted that Cutting and Early were at the back of the formation and “severely wounded, whereby they were taken to the aid station in Châtel Chéhéry with Mario Muzzi.” Private Patrick Donohue was also wounded but remained with the men.91

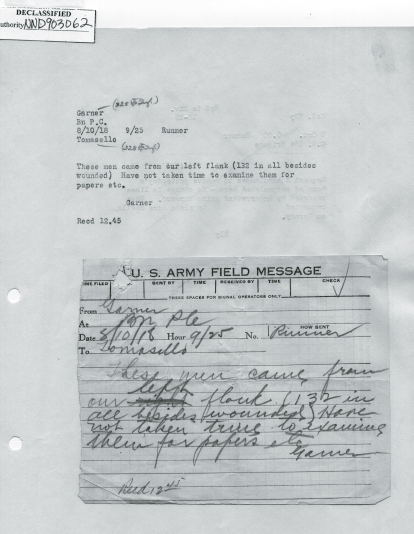

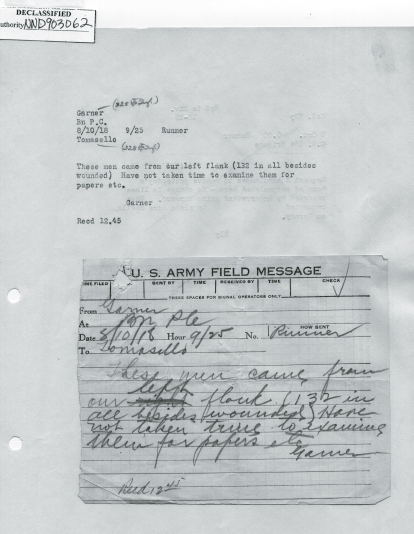

This is the original message sent to York’s divisional headquarters announcing the capture of 132 German soldiers. Brigadier General Lindsey saw York moving the prisoners through Châtel and said to him, “Well, York, I hear you have captured the whole damned German army.”

Meanwhile, a German artillery forward observer on Humserberg saw the large formation of troops near Hill 223 and called for artillery fire. As the shells began to land, York ordered the Germans to double time out of the valley. After they made it safely back to Châtel Chéhéry an American officer saw Vollmer and cut off his rank and Iron Cross. Vollmer protested but was told to shut up. The battalion intelligence officer quickly asked Vollmer a few questions and found the German orders to counterattack and seize Castle Hill at 10:30 in Vollmer’s pocket.92 Near Châtel Chéhéry the column was stopped by the brigade commander, General Lindsey, who said to York, “Well, York, I hear you have captured the whole damned German army.”93

The wounded Germans and Americans were helped off to the aid station in Châtel Chéhéry, with the Americans being told to walk the remaining German prisoners back to Varennes, some six miles south, as the regimental holding area could not keep so many. To keep control of the prisoners, various soldiers were solicited to help out, including a tank mechanic, Sergeant A. N. La Plante, of the 321st Company, 1st Tank Brigade, who was returning to his unit in Varennes. He testified that the Americans treated the prisoners kindly, stopping for rest breaks, and freely provided water to them. When the men at last made it to Varennes, the group stopped and was fed. After eating they headed for a larger prisoner cage near the village of Boureuilles.94 On the way, a 35th Infantry Division photographer snapped a picture of York and his German captives, being clearly identified by the presence of Vollmer, Thoma, and Lipp at the head of the group.95

York and his platoon frustrated the German plan and bagged a portion of Vollmer’s 1st Battalion, 120th Regiment, elements of the 210th Prussian Reserve Regiment, the Bavarian 7th Mineur Company, elements of the 2nd Machine Gun Company, and elements from the 4th and 6th Companies of the 125th Landwehr. This cleared the American front and left flank and caused the Germans to abandon more than thirty machine guns, which were recovered there after the battle. Because of this, the 2nd Battalion, 328th Infantry Regiment, was able to resume the attack.96 They continued up the valley to reach their objective, the Decauville Railroad and the North–South Road. This placed the flanks of the 120th and 125 Landwehr Regiments at risk. The German line was broken, and the 120th Landwehr would never recover from the loss.97 The report of the 120th Regiment said:

This photo was taken outside of Varennes-en-Argonne and is confirmed to be of York’s group of prisoners. The three German officers in the front of the formation each played a central role in the 8 October battle. At left is Leutnant Paul Vollmer, the commander of 1st Battalion, 120th Württemberg Regiment, who personally surrendered his unit to York after losing many men and seeing his friend Fritz Endriss fall in combat. The German officer in the center is Leutnant Max Thoma, commander of the Bavarian 7th Mineur Company, the officer who refused to surrender unless Vollmer accepted responsibility, and to the right is Leutnant Paul Lipp, who commanded the 125th Württemberg machine gun that killed or wounded half of the Americans with York. The American in the center of the photo, just behind the German officers, is Alvin York. (AHEC)

Several 7th Bavarian troops evaded capture and reported that the Americans had broken through and captured over a hundred Germans. The command had trouble believing that this could happen to Vollmer, who was known as a confident, reliable, and proven soldier. A patrol was sent out to ascertain what happened. When reports reached the 2nd Landwehr commander that the line was breached by an American surprise attack, General Franke took action and placed the 122nd Landwehr Infantry Regiment in the gap as a temporary remedy. They deployed on a reverse slope defense in the deep ravine about 600 yards south of the York site. This is where a delaying action was fought by the Germans around 2:00 P.M.98

Although there were fears of other American penetrations, there was no panic among the 2nd Landwehr. The unit adjusted its line back to resist further American advances. Portions of the 45th Prussian Reserve Division were unnerved when word reached them that the line was broken, which compelled General Franke to deploy his reserve cavalry squadron to restore order. Despite this, the Argonne was all but lost. The planned counterattack to take Castle and Beautiful View Hills was preempted by this American surprise attack. The 2nd Landwehr lacked the manpower now to conduct the operation or to even hold the line against the Americans. If the 82nd Infantry Division pressed the attack now, it would result in the capture of thousands of troops, supplies, and artillery.99 Fortunately for the Germans, the 328th U.S. Infantry had taken a beating as well and did not take advantage of the opportunity. Shortly after this, the order to withdraw from the Argonne was given to the embattled German army:

A temporary line was established slightly back in the Argonne to give the command time to evacuate its troops from the forest. A counterattack was made north of the valley against the village of Cornay. This German attack drove the Americans from Cornay, capturing about one hundred U.S. soldiers.101 On 9 October 1918, the final order was issued to evacuate the Argonne and to withdraw into the fortified Siegfried Line for the final defense before the war ended.102 “It was now that … the leader of 5th Army, gave the last word. We needed to occupy the secondary defensive positions further back. In the evening of 9/10 October, the regiment departed from the Argonne. The German soldiers gave so much after hard battles since 1914—more than 80,000 dead were left here. American artillery briefly hit the Humserberg line during the retreat and always there were the shrapnel. By Cheviers, the Regiment was in shelters. We were dead tired, too tired to contemplate, but able to hold onto hope.”103

Yet, before the Germans retreated from the Argonne, York and his men would clash with the Germans one more time.