10

Back on the Farm in Pall Mall

The war forever radically changed the world. Four Old World empires vanished (the Ottoman, German, Austro-Hungarian, and Russian), and four ancient dynasties ended (the Hohenzollerns of Germany, the Hapsburgs of Austria, the Romanovs of Russia, and the Ottomans of the Turks). Twelve million died directly from the effects of the conflict, and up to 100 million more in the Spanish influenza plague that swept the world after the war.1 The map of Africa was redrawn, and in the Middle East and Eastern Europe new nations sprang forth, some out of the victor’s imagination. Life had changed, and it was York’s desire for the folks of Pall Mall to catch up with the world, or risk being consumed by it.

With Bible and rifle in hand, Alvin went to his prayer spot on the mountain to contemplate his new dilemma.2 His prayers were answered quickly, and he believed that God had equipped him for taking on the challenge of bringing changes to his valley. Reflecting on this, Alvin said:

And then there was Alvin’s fame. He was willing to accept the Rotary Club initiative to provide him with a farm.4 It did not seem right to take more.5 Yet, he left the door open to accept an offer that would glorify God and honor his fellow soldiers.6 The key ingredient for York was that as long as he was not acting on selfish gain, he could use his notoriety to help others. With this in mind, he saw it morally right to use this fame for the improvement of life for his people, especially that of the children.7

Alvin saw three things that were needed in his community: roads, vocational schools, and the expansion of Christian teaching. He wasted no time getting a good road built into Pall Mall. Using his clout and the influence of the Tennessee governor, he visited the State Highway Department in Nashville, who soon began work cutting a good road across the mountains into Pall Mall. This road is now a ten-mile portion of U.S. Route 127 linking Pall Mall to Jamestown. Called the “York Highway,” it gave the valley access to the outside world.8

Next came the most difficult to achieve, building a school. Based on the notion that he would use his fame to raise money, Alvin established the York Foundation. The foundation was a nonprofit association that would serve as the focal point for raising funds to build schools in the region. His desire was that the foundation would not only pay the construction costs, but also the teachers’ salaries and the maintenance of the facilities. York wanted to ensure that the next generation had the education that he never received—and with it, a greater chance of success.9 Additionally, it was imperative that the schools provide scholarships so that every child could attend regardless of their parents’ financial state.10 He desired that the children be provided a high-quality education that would first teach the basics, and then vocational skills. Alvin thought that the vocational aspect should focus on skills needed in the region, such as animal husbandry, carpentry, dressmaking, farming, fruit tree growing, home economics, etc.11

With this vision, York took to the road to raise funds in the fall of 1919, which turned into a trip across the nation. He was assisted by his friends in the Nashville Rotary Club, who made arrangements with Rotarians around the country to plan and organize events to support Alvin’s foundation. Traveling with Gracie for a portion of the journey, Alvin was received by large crowds and excited ovations. Naturally, they wanted to hear about his war experiences, which York continued to shy away from. His tour, although having a good start, was cut short. After a speaking engagement in Boston, Alvin suffered from acute appendicitis, forcing him to abruptly end that round of visits. This was the first in a string of health issues with which he would wrestle.12 Despite this, his fund-raising was off to a good start, which he would continue through 1920 in New York, Pittsburgh, Chicago, and many other cities.13

Nevertheless, York’s personal financial situation took a turn for the worse in 1921. The problem was that the Rotary Club failed to raise enough money to cover the cost of the farm, and Alvin simply did not have such money. E. J. Buren, a writer for The World, published a moving article in the Washington Post that was the first to help the public understand York’s financial problems and the truth about the farm. Buren wrote that although the Nashville Rotary claimed to have purchased and given the farm to Alvin York, it had not done so as of December 1921. This had not happened as they still owed a considerable amount of money on the property because their donation solicitations had fallen well below what was needed. Because of this, Alvin, Gracie, and then eight-month-old Alvin Jr. were still living with York’s mother.14

Upon hearing of York’s financial dilemma, the federal government attempted to ameliorate his indebtedness. Congressman Cordell Hull and Senator Kenneth McKellar, both of Tennessee, lobbied to vote through Congress a bill, House Resolution 8599, granting York retired status as an army lieutenant (under the House version) or a captain (under the Senate version). If passed, this would have provided him a modest monthly pay allotment.15 This included an appeal to Secretary of War Newton D. Baker, who answered the request with a hearty endorsement, noting that although it was an exception to policy, none deserved it more.16

As Congress discussed and debated the matter, the War Department’s enthusiasm waned and faded, especially when a new secretary of war entered the fray. This process dragged on for nearly a decade. By 1928, the bureaucracy prevailed, with Secretary of War Dwight F. Davis paying lip service to Alvin York but laying down all the reasons why he should not receive such a benefit. Davis claimed that doing this for York put the national defense at risk by paying out annuities to inactive members, saying that the Congressional Medal of Honor was sufficient recognition of his heroism.17

The congressional effort to commission York as a retired officer with pay benefits would go on for sixteen years before the bill was passed.18 By the time the bill reached the president for his signature it was 1942, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt was in the Oval Office. He signed it into law without question.19 No doubt the outbreak of the Second World War was the only thing that made this possible. The bill promoted two Great War heroes to major: Alvin York and Sam Woodfill. Woodfill and York were two of the three greatest heroes of the First World War according to General Pershing.20 The third, Major Whittlesey, the commander of the Lost Battalion, was given no benefit as he had died in 1921.21

The 1920 public did not know that these initiatives to help York had failed and assumed that he was taken care of by his nation. When asked by E. J. Buren when was the last time he received anything from the U.S. government, York replied that he received $60 on 30 May 1919 as his final pay from the army.22 Since then, there was nothing.23 In this he was treated no differently than any other AEF veteran. This was all the pay and benefits any soldier would receive coming back from the Great War. Alvin expected no more.

The misperception about Alvin’s housing situation started on his return from France in May 1919. While being escorted around New York City, he was told that the Nashville Rotary Club had not only purchased the land and the farm, but that it was his without any debt or hitches.24 However, this was not so. The massive 410-acre farm had been purchased for $23,000, with the Rotary raising $10,937.50 of the cost, leaving York with the burden of paying the remaining $12,062.50.25 This did not include the extra $15,000 that it would cost to have a home built on the farm, with barns, etc.26 Raising such money was nigh impossible for York even in a good farming season. The year 1921 proved particularly difficult, and even though York worked night and day, “His hay was practically burned up and other crops failed.”27 Although Alvin appreciated the Nashville Rotary Club’s generous donation, this was more than he could handle financially, especially as he also had to purchase $3,000 worth of machinery and animals to start working the land. This placed him, for the first time in his life, in a debt that he could not pay no matter how hard he worked.28

To get out from under this crushing debt, York’s friends urged him to sign a film or vaudeville deal to raise money. Alvin refused to compromise on the matter, saying that the same God that brought him safely through the war would likewise also safely see him through this trial.29 Of this he said, “My conscience told me that both propositions were wrong and I refused to consider them at any price.”30 York added during a speaking engagement at Asbury College that “he would rather be ‘a pauper and homeless knowing that he was serving God and would have a Home in heaven.’”31 This moral stance earned him condemnation in some circles, by individuals who saw nothing wrong with taking the expedient way out of his financial crisis and selling his story to vaudeville. Some of the critics were so angered by his morality against signing stage deals that they not only withdrew their pledges to help pay off the farm, but also slandered his performance as a soldier. When asked to respond to the personal attacks, Alvin refused.32

The Nashville Rotary, with help from the local newspaper, attempted to raise the remaining money but could not, and members told E. J. Buren that it looked like they would fail in even making the next payment. Nevertheless, the matter gained national attention, garnering an outpouring of support for Alvin. The Tennessee Society of New York again rose to the occasion and solicited generous donations from its members. Additionally, the Chicago Tribune, Edgar Foster of the Nashville Banner, the New York Stock Exchange, and Marvin Campbell, an Indiana banker, used their influence and personal funds to raise money for the indebted and “homeless” sergeant.33

A fund-raising drive to provide York with the money he needed by Christmas was undertaken across the nation in 1921.34 At last, the public had the truth on Alvin’s financial need and rallied to pay off his land and house. With a heart of thanksgiving, York was given the deed to the land, and he thanked both America and God for providing for his needs. Several years after the land was pledged to him, work could begin on a house for Alvin, Gracie, and their growing family.35

Although facing mounting debt, York refused to give up on his dream of building schools for the children of his area. By 1922 he had collected $12,000 in hard cash (in the York Foundation Fund) and had a further $20,000 in pledges. True to his morals, 100 percent of the money raised in this endeavor was strictly for the construction of schools. A board of advisors was appointed to dutifully and faithfully monitor the use of all York Foundation funds, as well as to ensure the integrity of this undertaking.36 Yet, he set aside none of this money to cover taxes, something the IRS would come after him for later.

In the midst of this, York received a boost in notoriety with the publication in 1922 of a book by Sam Cowan called Sergeant York and His People.37 Cowan claimed to hail from York’s region of Tennessee and took an interesting approach to the story. Instead of making Alvin’s military exploits the center of this work, he focused on life in Appalachia. As the New York Times review of the book said, “Mr. Cowan has utilized Sergeant York as the ‘peg’ upon which to hang a more or less intimate description of the people of the Cumberland Mountains.”38 To develop this portrayal of the mountain life, Cowan spent two months living in Pall Mall and witnessed the now legendary turkey shoots, the logrollings, and the importance of the Christian faith to these people. Cowan was spellbound by the simple yet difficult life that these Appalachian Tennesseans lived. It was because of this, Cowan suggested, that men such as Davy Crockett, Daniel Boone, and Alvin York exist.39 Yet sales of the book were disappointing, as interest in the Great War had already faded in the United States.

In the meantime, York continued criss-crossing the country over the next several years to raise money for his schools. A major breakthrough occurred when the State of Tennessee and Fentress County each pledged $50,000 in support of York’s vocational high school in 1926.40 Meanwhile, the land for this facility was given by several generous donors. The county gave York 135 acres of prime land near Jamestown, while several lumbermen donated more than 1,235 acres for the endeavour. With these, in addition to the many financial gifts that had been safely tucked away in the York Foundation account in Nashville, it was time to start construction.41

The decision to build the school in Jamestown instead of Pall Mall was logical, as it offered the children from across the county an opportunity for an education in a central location. Because of this, York’s school would have to add dorms for those coming from farther out. On 8 May 1926, Alvin broke ground for what would be called the “Alvin C. York Industrial Institute” before the applause of some two thousand supporters. This first building would be made of stone and brick and was to be ready for use in the fall. Despite this, much work remained. Constructing dormitories and barns, clearing a pasture, and erecting a woodworking shop were all yet to be accomplished. The plan was to have ten teachers and two hundred students. While the construction was ongoing, the York Institute would formally begin in an old building across the street. The eighth anniversary of York’s 8 October 1918 battle (1926) was the appointed day to officially open the school, but this had to be postponed to 1927.42 Although Alvin proudly graduated his first class in May 1927, he would soon discover that fighting the Germans was easier than fighting local politicians.

The selection of the site in Jamestown pitted York against the local power brokers, who had been growing in their opposition to him. Although York leveraged his popularity to push through his agenda, he would find that this tactic could only go so far. Alvin would soon discover that “a prophet is not without honor except in his own town and in his own home.” There was a segment of influential officials and rich businessmen who resented York’s celebrity and political power. They made up half of the board of the York Foundation.43 Although Alvin had powerful political friends in Nashville and Washington, the local faction was scheming to push him aside as quickly as possible. Alvin soon found that it was easier to work with people outside the region, who did not have agendas or ambitions to sidetrack his vision for educating the area’s youth. He also felt acutely betrayed by these former “friends” who had turned against him. The challenge he faced was daunting. “The Board they give me couldn’t see things the way I did. So I have had a most awful hard fight, a much worser one than the one I had with the machine guns in the Argonne.”44

The local power brokers included a list of influential Fentress County figures: W. L. Wright, the Bank of Jamestown president; Judge H. N. Wright; J. T. Wheeler; County Superintendent Ocie O. Frogge; Ward R. Case; George Stockton; and W. E. Porter.45 They seemed to oppose his every move. Alvin was only able to break the impasse by holding public hearings, which won local support and state government intervention.46 Yet, the local power brokers did all they could to stymie his school, with the aim of pushing York out of the way altogether. In their defense, they did have a different vision as to how the York Foundation and school should be run. York lacked formal education, lacked qualifications to run the institution, and was inclined to install similarly unqualified friends and family into key positions. Meanwhile, those opposed to him preferred to install qualified people with professional educational experience. As the driving force behind the effort, York wanted to keep control of his institution. With these polar opposite views, things were about to come to a head.47

The bickering forced York to initiate legal action against those whom he saw as standing in the way of the school, causing him much anguish. In one incident, York had the furniture and equipment removed from a temporary school building so that the court would have to decide who had the legal right of its use. In the midst of this, Alvin continued to raise money for the school while trying to take care of his family and farm.48

After losing the support of the local power brokers, it became difficult for Alvin to run the institute. He appealed to the state to intervene, and in response the Tennessee government took over the York Institute in 1936, much to Alvin’s chagrin. This was the price of overcoming the local power brokers.49 Understandably, not having a formal education put York at a distinct disadvantage with the state administrators, who forced him to resign. As a consolation, the Prohibition Party named Alvin as its 1936 vice presidential candidate the same week that he lost control of his school, an honor that he graciously declined.50

Despite the tribulations, York had accomplished the impossible, and the school is still vibrant and active today. He brought education to his region and thereby gave his people opportunities that he had lacked. Without his tireless leadership, this project never would have come to fruition.

Throughout the seventeen-year odyssey to raise the Alvin C. York Institute, Alvin poured his heart and soul into the work. His family and farm suffered for this, with him gone so much trying to raise funds to make the dream a reality. With every speech, Alvin was asked about the Great War, something he shied away from or downplayed.51 All he wanted to discuss was his school and the kids in Fentress County. In exasperation to a war question, he answered: “I’m trying to forget the war. I occupied one space in a fifty-mile front. I saw so little—it hardly seems worth while discussing it. I’m trying to forget the war in the interest of the mountain boys and girls that I grew up among.”52 He only slowly grasped the idea in 1927 that it was the war that drew the crowds and provided the donations to build his school. It fell to someone whom York had never met to come into his life with an idea on how to address this. That person was Tom Skeyhill, who had witnessed York’s arrival in New York in May 1919.

In 1927, Skeyhill made his way to Pall Mall to convince York to write a biography. At first York refused, but after “reminiscing of old days of the front,” Skeyhill convinced him, saying that the money earned from this could be used to build and expand the school for mountain children that he so desired.53 Skeyhill would help York by serving as the book’s editor.54 Tom Skeyhill proved the right choice. He convinced Liberty Magazine to invest $40,000 to buy the rights for a two-part serial release of portions of the book in the summer of 1928. He also secured an agreement with Doubleday for a nationwide release of the completed book later in 1928, titled Sergeant York: His Own Life Story and War Diary.55 In 1930 Skeyhill worked with York to publish a children’s version of his story, which included Appalachian pioneer vignettes. That book was Sergeant York: Last of the Long Hunters.56 To write these books, Skeyhill imitated Cowan’s idea of spending time in the region watching everyday life, turkey shoots, and church services. But he also had a grasp of life as a soldier. Because of this, he surpassed Cowan’s work.

Skeyhill helped York put together a well-presented biography. The book’s strength was that it laid out a convincing case of the evidence supporting York’s actions on 8 October 1918. This was to answer what Skeyhill suggested was a common reaction to the story. “At first I was skeptical. Who was not? It sounded too much like a fairy tale. It just could not be done. It was not human. Yet it was done,” he wrote in the preface of his book.57 To answer such questions, Skeyhill included affidavits as well as portions of the investigation that the AEF conducted in February 1919. The book was a resounding success and was quickly followed by the “boy’s” version of the story, Sergeant York: Last of the Long Hunters. The latter book was dedicated to Alvin’s sons, Alvin Jr., George Edward Buxton, Woodrow Wilson, Sam Houston, and Andrew Jackson.58

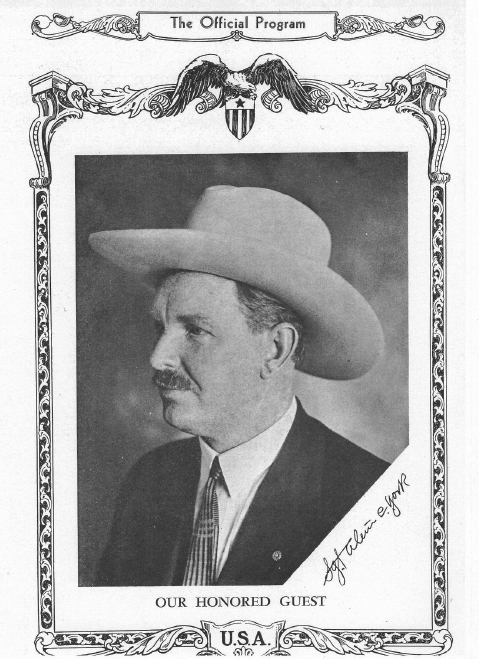

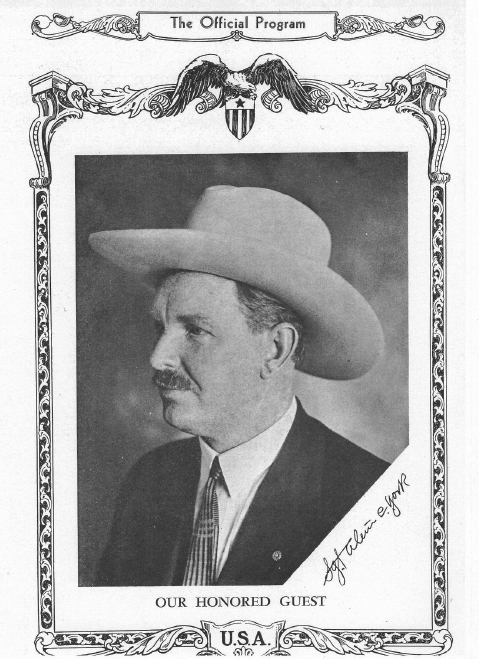

York on the 1929 cover of the U.S. Army War College Annual Exposition. The U.S. Army featured York as its guest of honor during its annual expo in Washington, D.C., in 1929, which included an exaggerated reenactment of his 8 October 1918 battle. (AHEC)

York continued to travel around the country raising money for his school. It seemed that America could not get enough of him, and with the story out at long last, perhaps the clamoring for war stories from him would end. However, between 3 and 5 October, the U.S. Army War College conducted its annual fair in Washington, D.C., with the highlight of the exposition being a twice-daily reenactment of the Sergeant York action.59 The “Smashing through the Argonne with Sergeant York” show drew ten thousand spectators each day. The exposition included displays of the U.S. Army’s and U.S. Air Corp’s latest weapons.60

To reenact the York action accurately, the U.S. Army assigned several officers to go through the archives and to interview eyewitnesses. However, the officers could not find maps that accurately depicted the location in France. To fill this historical gap, the researchers contacted Buxton and Danforth. The problem was that neither of these officers was an eyewitness to the action and therefore both had to rely on second-and third-hand information to develop their own grossly inaccurate sketches.61 Despite this, the army made the best of what it had to support the reenactment. These grossly inaccurate maps would later mislead future investigations in France trying to find the York site.

York and the surviving members of his platoon were invited as guests of the U.S. Army to participate in this event. The expo culminated with the presentation of the Distinguished Service Cross to Sergeant Early for leading the sixteen men into the German flank that morning in 1918. Among the others invited from York’s outfit was Corporal William Cutting.62 Having enlisted under the false name of William Cutting, Otis B. Merrithew had begun a campaign in the early 1920s against the U.S. Army to secure an award for himself, and claimed that it was he who took over when Sergeant Early fell, not York.63 It will be remembered that Merrithew confessed to a personal dislike of Alvin York while they served together in the 328th Infantry Regiment. Ironically, the difference between the two remained stark. York wanted to forget the war and would rather talk about his school, while Merrithew continually talked about the war and wanted others to know his point of view on this matter.64 To set the record straight, Merrithew began a letter-writing campaign to local newspapers in 1920. Having not achieved headway there, Merrithew found another way with his invitation to the 1929 Army War College Exposition, which put him in contact with Danforth, Harry Parsons, Buxton, and the other squad members.

Nevertheless, his endeavors to get a medal were not supported. Cutting’s platoon sergeant, Harry Parsons, flatly rebuffed him. This was the same Parsons whom Cutting claimed he handed the prisoners to on Hill 223. Of this, Parsons said in his thick Brooklyn brogue, “It was York’s party. … It was York’s Battle.”65 To be sure that he was understood, Parsons added in another interview that he rejected Cutting’s allegations, saying, “Alvin York deserves every bit of the credit given him.”66 Cutting also hit a dead end with his former company commander, Captain Danforth, who rejected the assertion that Cutting was the hero of the battle, saying, “Credit was given where credit was due.”67 Cutting’s last avenue was Colonel Buxton. Buxton was not at all involved in the action, and instead was far from the battle and working on the division staff in October 1918. Buxton, ever judicious, offered to review any facts that Cutting could present.68

The Army Exposition not only put Cutting in contact with his squadmates, but with the press as well, who were attracted by the controversy regardless of its merits. As for Cutting’s demand that he be awarded a Silver Star, Buxton refused to support him because the affidavits that Cutting produced were too vague to support his side of the story, but the colonel did tell him that he was authorized the Purple Heart. The only concession given was by Brigadier General Lindsey, who mentioned Privates Wills, Beardsley, and Kornacki in his brigade commendations report in 1919. Lindsey conceded that all the men in the attack should have been listed therein.69

Buxton was quick to point out that the facts were with York, saying: “All investigations by those in authority and the affidavits of the surviving enlisted men clearly indicate that York bore the chief burden of initiative and achievement in the fire fight and during the later stages of the engagement.” Buxton was quick to reject the press-generated hyperbole about York’s feat being “single-handed” or that he was a one-man army.70 Neither York nor the U.S. Army ever made such a claim; it was the media that created that notion. Although willing to provide Cutting with advice, and a listening ear, Buxton could not throw his support behind a claim that lacked material evidence. Despite this, Merrithew would persist in his undertaking to receive a medal to the end of his days.71