Arnold Beauregard liked to think of himself as a modern-day cowboy. His family had first come to Louisiana in the 1720s. To this day his mother insisted to anyone who would listen that, yes, Beauregard was French, but that their ancestry was Creole. True French aristocracy rather than that Johnny-come-lately Cajun riffraff that had begun trickling into Louisiana in the 1760s.

Fact was, the clinging fingers of the past still pulled at old Louisiana families. But for Arnold, the lure was the Old West, not antebellum plantation life. In his dreams he was a cattle baron, not a cotton king.

The SUV, a Toyota Land Cruiser, could be seen waiting just past the gate as he turned into the farm lane off Route 577. He pulled up and stopped his brand-new white Chevy one-ton duly behind the Toyota before shutting off its big diesel engine.

Picking up his cell, he punched the office number and, at the secretary’s voice, said, “Julie, I’m at the Hoferberg place. Those archaeologists are already here. I’ll have my cell on if anything comes up.”

A genuine straw Stetson was perched atop his black crew cut. The left breast pocket of his Wrangler snap shirt outlined an obligatory can of Copenhagen. A tooled-leather belt snugged his waist while six-hundred-buck Lucchese razor-tips peeked out from under his creased boot-cut jeans.

Yep. One hundred percent cowboy.

The irony, of course, was that his business was farming, not ranching. Not the actual sweating-in-the-sun-and-driving-the-tractor kind of farming, mind you, but administration.

He stepped out of the Chevy and walked toward the people climbing out of the Toyota. His first thought was to glance at his watch. If this didn’t take too long, he could check on fertilization and field prep over at the Badger Unit this side of Alsatia and be back to Delphi in time for lunch.

“Mr. Beauregard?” A tall thin man called from the Toyota’s driver’s side. He wore bifocals and looked about fifty, with a neatly trimmed beard and brown cotton pants. To his right stood a blond woman, medium height, perhaps thirty, in jeans, long-sleeved shift, and hiking boots. She had a pensive expression—and eyes way too intelligent to be in a face that pretty. Next to her was a grungy-looking kid, maybe twenty-five, with long bushy brown hair pulled back in a frizzy ponytail. He had on a checked shirt, baggy cloth pants, and running shoes that had to have been stolen off a bum on Bourbon Street.

“Call me Arnold,” he answered, extending a hand. “You’re from the university, right?”

“Dr. Emmet Anson,” the bearded man said as he shook.

“I’m Patty Umbaugh,” the pretty blonde said. “I’m with the state. Department of Culture, Recreation, and Tourism.”

He smiled thinly. The state? What the hell did they have to do with this?

“Rick Penzler,” the longhair told him, giving him a cool, somewhat arrogant look.

“My pleasure,” Arnold answered evenly, turning this attention to Anson. “Dr. Anson, you asked for a meeting concerning the Hoferberg property. Said it had something to do with some dead Indians?”

Anson nodded. “That’s right. A couple of years back we did some work on the mounds out back there.” He pointed down past the house and barn toward the bayou. “Mrs. Hoferberg had talked about taking steps to protect and preserve the site. She had mentioned that when the time came to sell the property, that we might be able to come to some sort of agreement.”

Arnold stuck his thumbs in his belt, saying, “I see.” That bought him time while he considered. “Well, I don’t know anything about any site here. The thing is, the bank foreclosed on the Hoferberg farm, Dr. Anson. Our dealings have all been through the bank when we acquired title to this property Any questions relating to that would have to be directed to Otis, our attorney.”

“Yes, we know,” Patty Umbaugh said seriously. “The reason we called this meeting was to see if we could come to some agreement—with your corporation, of course—concerning the archaeology.”

Arnold gave her his winning cowboy smile. “Well, that would depend, I suppose. We’ll be happy to hear what you have to say.”

From the look Penzler was giving him, you would have thought Arnold had wrapped tape sticky-side-out on his fingers when the collection plate went by of a Sunday morning.

“Why don’t we drive down and show you what we’re talking about,” Anson suggested. “It’s kind of boggy down there.” He glanced at the shining Chevrolet. “Want a ride?”

“This won’t take long, will it?”

“Half an hour?” Anson asked, raising a hopeful eyebrow.

“Let me get my cell phone.”

He stepped back to his truck, unplugged his cell, and stuffed it into his shirt pocket. By the time he walked up to the passenger door, Umbaugh and Penzler had climbed into the back. Anson was at the wheel and turned the key as Arnold slammed the passenger door.

“What do you do, Mr. Beauregard? For BARB, I mean?” Anson asked as they started down the tree-lined lane.

“I’m the operations supervisor. That means I drive from farm to farm, seeing to it that the local managers are doing their jobs and that everything is running smoothly. I act as the corporation’s eyes and ears in the field. Rambling troubleshooter and problem solver.” He chuckled as he pulled out his Copenhagen and took a dip. “I guess you’d say that I’m the feller that makes the machine run.”

“What does BARB stand for?” Prenzler asked flatly. “What does it do?”

At the tone in Prenzler’s voice, Arnold fought the urge to crane his neck and spit snoose on the kid’s filthy shoes. “It’s short for Brasseaux, Anderson, Roberts, and Beauregard. We’re the board. We buy up bankrupt family farms in northern Louisiana and southern Arkansas, recondition the soil, and make them pay. Our equipment is stored and serviced at our shop several miles east of Monroe. In all, BARB runs more than six hundred thousand acres of agricultural property.”

He smiled down, admiring his expensive boots. If truth be told, neither BARB nor Arnold even owned a cow. Still, he never missed a rodeo, and his daughter, Mindy, had a beautiful barrel horse that she kept in the stable at their elegant house north of Monroe.

“Take this place.” Arnold flipped his index finger around in a circle. “We’ll have a crew in here next week to take out these trees.”

He waved expansively at the lines of stately oaks that shaded the lane.

“Take out the trees?” Penzler asked incredulously.

“And these buildings.” Arnold nodded at the white frame house and shabby-looking barn as they drove into the yard. They stood empty now, looking forlorn. “Our crew will salvage what we can from the structures, anything we can sell for scrap. Then we’ll bulldoze the rest.”

“Why?” Umbaugh asked, concern in her voice. She was looking longingly at the old red barn, its huge door open to expose an empty gloom.

“Miss, uh, Patty did you say? You gotta understand. This house and barn, these trees, shucks, even this lane we’re driving on, isn’t in production. The margin in American agriculture is about as thin as a’skeeter’s peter. It’s because in this country we have the cheapest and best food in the whole world. At the same time, urban sprawl and development is taking millions of acres a year out of production. At BARB we grow food, and we’re good enough at it that we can still make money.”

“Six hundred thousand acres?” Penzler asked hostilely as Anson passed the barn and followed a two track between two large fallow fields. A quarter mile ahead, trees rose in a gray thicket, barely starting to bud in the late-March warmth.

Arnold couldn’t stand it. He turned, letting his gaze bore into the squirrelly kid’s cold blue eyes. “You might ask Mrs. Hoferberg how much she made on this place these last few years. This farm has just over a thousand acres of good land under cultivation. Mrs. Hoferberg was sixth-generation—going clear back to the civil war. Hell, her great-great-great-granddad waved to U. S. god-damned Grant when he went by on his way to Vicksburg. The family farm just can’t cut it in a global economy.”

“So you plow it all up?” Penzler asked.

“Productivity drives the country,” Anson said easily. “Myself, I’m not so sure I wouldn’t rather just go back to the good old days. Fish, hunt, raise a few cows, and grow a garden. Life would be so much simpler.”

“Suits me,” Anson said easily as he skirted the fallow field.

“You hunt, huh?” Arnold glanced at the bookish-looking Anson.

The professor smiled. “Hey, I grew up in Melville, down on the Atchafalaya. When I wasn’t running a trotline I was after ducks or rabbits with my old 20 gauge. Went to Harvard on scholarship, so I had to lose the accent.”

Arnold nodded. “What got you into archaeology?”

“Hunting and fishing,” Anson said with amusement. “I wanted to know how people made food before John Deere and Cargill.”

Anson followed an overgrown track into the trees, dropped down through a marshy area, and up over a hump of dirt. Pulling to a stop, he looked around and shut off the engine. “This is it.”

Arnold opened the door and stepped out. Overhead, branches wove a gray maze against the cloud-speckled March sky. Irregular humps in the land could be seen. It reminded him of a brown, leaf-covered golf course. “What am I supposed to be seeing here?”

Umbaugh stepped up beside him, pointing to the contours of land. “This is a Poverty Point period mound site. It dates to about thirty-five hundred years ago.”

“Poverty Point?” Arnold cocked his head and spit some of the Copenhagen floaters onto the damp leaves. “Like the state park down the road a piece?”

“That’s right. Have you been there? Seen the museum and earthworks?”

“Naw. I just drive through. It’s old Indian stuff, isn’t it? You seen one pile of dirt, you’ve seen them all. I mean, hey, they ain’t coming back.”

He could sense Penzler’s blood beginning to foam.

Anson walked around the front of the Toyota. “Personally, I wish they would. I’ve got a half a lifetime’s full of questions to ask.”

“Like what?” Arnold followed Anson up onto the low embankment of earth and looked around. For all the world, it looked to him like old levees and meander bottoms.

Anson had a curious gleam behind his bifocals. “The pyramids were new when these people built the first city in North America. You’re in agriculture, you can understand the problem, Mr. Beauregard. How do you build a city like Poverty Point, organize the labor to move over one million cubic yards of earth, and do it without agriculture?”

“What do you mean, without agriculture? You gotta have agriculture. Tell me how you’re gonna be Bill Gates and invent computers when you’re out for half a day hunting and fishing for each meal.”

“Tell me indeed,” Anson agreed. “But they did it. Right here in northern Louisiana, they created a miracle.” He turned, waving his arm in a circle. “Everything started here. It’s Egypt and Babylon. Moses and Ramses. I can feel it in my bones.”

“God, here he goes again,” Penzler muttered, walking off a stone’s throw to study the low mounds.

When he was out of earshot, Arnold asked, “Why is he here?”

Anson’s lips bent in amusement. “He’s finishing his Ph.D. on

Poverty Point trade relationships. He’s got this idea of interlocking clan territories regulated by the redistribution of resources.” Seeing Arnold’s look of incomprehension, he added. “Like groups of relatives that trade back and forth to keep the family together. That sort of thing, but on a larger scale.”

“What was that bit about Egypt and Moses? What’s that got to do with Louisiana?”

“It’s the same period of time.” Anson pointed at the low earthworks. “Sure, these people didn’t build huge cities of stone. They didn’t leave us records of their leaders, or their laws. But they did something that the Egyptians, the Babylonians, the Hittites, and all of their Old World contemporaries didn’t.”

“What was that?”

“Back before the first Pharaoh even thought of a pyramid, the people at Poverty Point put together a cross-continental trading system. But their most important gift to the future was an idea.”

“Or so you think,” Patty Umbaugh chided. Glancing at Arnold, she said. “We’ve barely scratched the surface here. We haven’t even investigated a tenth of a percent of the archaeological sites in Louisiana. If Dr. Anson is right, we’re sitting on a wealth of revelations about these people.”

Arnold cocked his jaw, considered, and asked point-blank. “What is your interest in our farm. So far as I know, this site is on private property.”

Umbaugh nodded. “Yes, Mr. Beauregard, it is. Louisiana has over seven hundred mound sites that we know about. Hundreds more that we don’t. Perhaps thousands have been destroyed by field leveling, and others have been hauled away over the years for highway fill, causeways, and levees. We would like to work with you in the preservation of this site. We have programs—”

“Yeah, yeah, I know about government ‘programs.’ It sounds so good. ‘We’re from the government, we’re here to help you.’ Next time you turn around, you’re in noncompliance with some damn thing. That, or some EPA or OSHA asshole is poking his nose up your bohungus to certify your fertilizer, or check the green cards on the hired help, or the frogs are being born with too many legs, or some damned thing.”

“I know, but our program—”

“With all due respect, Ms. Umbaugh”—he gave her the ingratiating smile again—“we would like to politely refuse your help.”

“Well,” she said with a sigh, “thank you for at least letting me come and see the site. I’ll leave you a card, and if you ever have any questions—”

“Yeah, right, I’ll call.”

Anson turned, head tilted. “Mr. Beauregard, I can sure understand your attitude about the government.”

“You can?”

Anson nodded. “Out of fear of the government, some of the most important mounds in the state have been bulldozed by worried landowners.”

“They must have snapped those guys’ butts right into court before they could grab their hats.”

“It was private property,” Anson replied laconically. “Just like your farm here. I’d hope that we’ve all learned our lesson. You see, the reason we’re here is that you are the legal owner of this site. We want to let you know what you have here, and why it is important.”

“What’s it worth?” he asked absently, squinting at the mounds of dirt. Just at rough guess, he figured it at about ten thousand cubic yards.

“Worth?” Anson shrugged. “In dollars, not much. But when it comes to information—to the questions we can answer—it’s priceless. This is a satellite site, an outlier tied to the Poverty Point site a little ways up Bayou Macon.” He pointed to the thicket of trees that dropped off toward the muddy bayou no more than fifty yards beyond the brush.

Patty Umbaugh said, “We have a registry of sites—”

“Nope!” Arnold shook his head categorically. “First you register it, then every tourist in the damned world wants to trespass on your property to see it, and some government bureaucrat wants to tell you how to run it.” He waved a finger. “The answer is no. Period.”

She looked pissed, but he had to hand it to her, she did a good job of covering.

Anson rubbed his jaw. “If you don’t want to work with the state to preserve the site, that’s fine. Would you mind, however, if we brought field schools, students, up from time to time to dig here? Everything that we find belongs to you, of course. You can keep the artifacts here, or at your corporate headquarters, or we would be happy to curate them at the university.”

Arnold rolled his lip over his chew, and slowly shook his head. “I don’t think so, Dr. Anson. First off, there’s liability to think about. What if one of your students fell and broke his neck, or some such thing? Or they snuck in at night to dig for arrowheads? And third, sure, BARB might own this site free and clear now, but who’s to say what’s gonna happen in the future? I heard tell of folks got taken to court over down by Lake Charles by some Injun group over a burial ground. We don’t need those kinds of headaches.”

Anson looked as if he were about to throw up. “But, you will preserve the site, right?”

Arnold smiled. Hell, cowboys and Indians never did get along together. “Yeah, well, we’ll take it under consideration. Like I said, either we’re efficient, or, well, just like your Indians. Extinct.”

Arnold squinted in the midday sun. The soft Gulf breeze blew up from the southwest. It sent puffy clouds sailing across the sky and brought the promise of afternoon rains. The big yellow Caterpillar growled and roared as it dropped the rippers and rolled a sweetgum stump out of the damp black soil. The roots popped and snapped like firecrackers.

The Hoferberg farm was unrecognizable now. The old oak trees that had shaded the lane had been cut down and sold for lumber. The house and barn, the foundation, the cisterns, and outbuildings had been flattened or plucked up with the backhoe and trucked off. Where the trees had somberly guarded the archaeological site, now an unrestricted view of the Bayou Macon could be seen; only the cane brakes under the slope of Macon Ridge remained standing.

Arnold had made a special effort to be here for the leveling. He’d never seen an archaeological site until Dr. Anson brought him here. And he sure as hell had never seen one scraped flat before. So he was curious. As the Cat cut great swaths through the mounds, he walked along with his cup of black coffee—because real cowboys drank it that way—in his hand. He spat his Copenhagen every now and then, and looked at the black dirt.

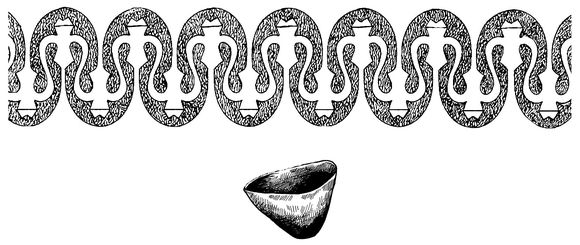

Most of Macon Ridge was a tan-brown loess, a silt blown clear down from the last glaciers up north. But the dirt in and around the mounds was crankcase-dripping black. Every now and again he had picked up one of the oddly shaped clay balls—finding them the perfect weight to fling out into the bayou—and wondered what the Indians had used them for.

Little flat flakes of stone came up, and yes, he had even found a gray-stone arrowhead a while back. He had wanted to find an arrowhead just as much as he wanted to see Indian bones come rolling out of the ground, but the rich loamy soil seemed against him on that one. All in all, there wasn’t much exciting to see. So how, then, could that Dr. Anson have spouted all that nonsense about ideas, and trade, and all the rest?

Out by the highway the big John Deere 9000s, brought in on

flatbeds, were already starting their runs. By noon tomorrow, the whole of Hoferberg farm would be disked, harrowed, fertilized, and ready for the trucks bringing the seed drills.

Arnold shook his head, disappointed at the bulldozing. He had expected something a bit more entertaining than featureless black dirt rolling under the blade. He looked again at the gray-stone arrowhead—a big thing, as long as his finger—and slipped it into his pocket as he turned to walk back to his truck. Glancing at his watch, he could still meet Harvey Snodgrass at the Delphi café and show off his arrowhead.

He was watching his razor-toed cowboy boots as they pressed into the damp black earth. The light brown polish looked so clean and fresh against the dirt. That’s when the gleam caught his eye. He bent, reaching down past some of the endless, oddly shaped clay balls, and picked up a little red stone.

With his thumb, he cleaned the clinging dirt away and stared in surprise. It was a carving. A little red potbellied stone owl. Something about it reminded him of a barred owl.

Arnold was more than a little intimate with barred owls, having shot his first one when he was fifteen. Not content just to leave it lay, he’d dragged it home to show off to his friends. Someone called the warden. But for quick work with a shovel, they’d have caught him with that owl. It had been closer than a’skeeter’s peter.

Turning the little red owl, he could almost believe that the craftsman who’d made it had carved a mask on the face. A masked owl? What did that mean?

Thing was, he couldn’t call up that Dr. Anson and ask. It wasn’t as if they’d parted on good company.

“Sorry,” he told the little owl. “Reckon your home had to go. Trees got to go down and crops got to go in. People can’t live without farming. It’s the future, little guy.”

He opened the door on his shiny new pickup, and paused, studying the little owl one last time before he put it in his pocket. “It’s not like your Indians are coming back.”

Thunder roared so close it was deafening. Arnold jerked his head up to stare at the sky.

The lightning bolt flashed white-blue, the clap-bang! startling the soul half out of José Rodriguez’s body where he sat at the Caterpillar’s controls.

“¡Madre de dios!”

With the afterimage of the flash still burning behind his eyes, José leaped from his idling Cat, and ran. He reached Arnold within moments. Rolling him over, José got his second fright for the day. The lightning bolt had done horrible things to Arnold’s head.

“Blessed Mother,” he whispered, and backed away.

José glanced at the tiny red owl that lay in the soil inches from Arnold’s fingers. It glinted in the storm light like a glaring eye.

José crossed himself, then he stumbled for the open driver’s door of Arnold’s pickup. The cell phone was fried. He had to get to a phone. Fast! As he cranked the wheel and sped away, the rear tires pressed the little red owl back into the rich black soil.