The fire popped and cracked, curls of thin white smoke rising from the dry wood. Pine Drop had built the rick in a hollow square, placing the cooking clays in the middle, where they would absorb the heat. The arrangement had to be made correctly so that the specially formed cooking clays heated to a white-hot glow in the center of the fire.

Normally water lotus was gathered for the great solstice feast, but the harvest had been so good this turning of the seasons that she had extra. It wouldn’t keep in the midsummer heat, so she had mashed the remaining roots in the mortar to form a sweet paste. One by one she had formed the cone-shaped cooking clays, indenting the convex side to resemble the lotus’s seedpods.

During the process, she sang the Harvest Song that recounted the origins of the lotus. In the beginning Mother Sun and Father Moon had both shared the Sky with equal duration and brightness. There was no night, no summer or winter, for when one dropped behind the horizon, the other waited until the first reemerged.

And then one day Father Moon glanced down and saw a beautiful woman bathing in a pond. She was the daughter of a great Clan Elder. His light shone in her long black hair and on her soft bronzed skin. He had never seen such a beauty before, and resolved to have her.

That night, when Mother Sun slipped behind the western edge of the world, Father Moon eased down from the Sky. He took the

form of a young man and found the pretty young woman. She had never seen such a handsome man before, and lay with him.

Meanwhile, the night Sky had gone dark. The animals that normally were awake, bats, raccoons, flying squirrels, and crickets were all running around, bumping into things, saying, “Where is Father Moon? What is happening?”

But Father Moon was busy locking hips with the pretty young woman. He was so involved that he forgot the time. Thus it was that Mother Sun peeked over the eastern horizon to find the world in darkness, and the animals of the night running around in panic.

“Where is Father Moon?” she asked, concerned that some terrible thing might have happened to her mate.

“He is lying with a beautiful woman,” opossum said. “He has left us in darkness so that he can lock hips with her.”

Mother Sun sent her rays over the earth, and sure enough, there was Father Moon, lying with the pretty young woman. Rage burned in Mother Sun’s heart, and in anger she fled to the south. She kept going and going, going so far that the world was plunged into darkness.

Horrified, Father Moon rose into the Sky, calling for Mother Sun to come back to him. But she refused, heading ever southward.

Father Moon chased after her, following her south across the Sky. As his light waned, Winter came roaring down from the north, cloaking the land in snow and ice. Plants died, turned different colors, and lost their leaves. Animals burrowed into the ground, desperate to save themselves from the freezing weather and the endless darkness. Birds, desperate for Mother Sun, flew south, many disappearing out in the gulf; where they ended up, no one knows.

In the end, it was Bird Man who, seeing his world dying, flew south after the birds. There he found Mother Sun sulking at the edge of the sea, where it joined the Sky. He told her of the cold, of the dying trees, and how the animals had burrowed into the earth. He told how Father Moon was so lonely that he had hidden his face in sorrow.

“If you do not come back, the world is going to die!”

Mother Sun listened, and realized that no matter how mad she was at Father Moon, she couldn’t let the rest of the world die. So it was she came back to the Sky, and the plants came alive, and people and animals were warm again. Seeing how grateful the creatures were, she shot beams of light onto the water, and a beautiful flower grew there. To this day the yellow lotus grows, its flower reflecting the face of Mother Sun. It is her promise to the world that she will always return to light the Sky.

Mother Sun never forgave Father Moon. That is why she forever moves across the Sky, always avoiding him. Father Moon still hides his face in shame and never glows as brightly as he did before the night he betrayed his mate.

Among the animals, bear, raccoon, the bats, the bees, and so many other creatures still hibernate when Mother Sun goes south with each cycle. In return, Mother Sun marks her return to the high summer Sky with the blooming of the yellow lotus. When the people harvest it for the solstice ceremony, its roots are sweet, and its flower resembles the face of Mother Sun so that people never forget her gift of life to them.

As she Sang the song, Pine Drop took damp lotus leaves from a stone bowl and wrapped balls of dough in the leaves. These she laid to one side on palmetto matting.

Her heating fire had burned down to coals, the central cluster of lotus-shaped cooking clays having taken on a white glow. She used a stick to scrape half of them onto a thin wooden platter and gingerly lowered them into the earth oven. As she poured them, she had to jerk her hand back from the searing heat.

“Hey, Cousin!”

She glanced up, seeing Eats Wood as he strode down the ridge. Sunlight shone on his muscular chest. His lightly greased skin reflected the light; his tattoos stood out as dark blue designs on his brown skin. Several necklaces of stone and bone beads hung around his neck, and he wore a green-dyed breechcloth. A mocking smile curled his round face, and his hair had been parted down the middle and cut short to bob just above his shoulders.

“Greetings, Cousin.” She shot him a polite smile and bent down to lay the first of her wrapped lotus-root breads onto the cooking clays.

To her irritation, Eats Wood knelt beside her, asking, “Can I help?”

“No. Just a moment.” She artfully laid the rest of the wraps onto the cooking clays. She couldn’t help but wonder what he wanted as she scraped the last of the cooking clays from the fire and shook them from the smoldering plate into the earth oven. She had never liked Eats Wood. He let his penis dominate any good sense he might have had. The parallels between Father Moon and Cousin Eats Wood couldn’t have been more clear. When she had placed the bark lid on the earth oven to seal in the steaming heat, she looked up.

“I just came to see how you were doing,” Eats Wood began. He gestured around at the ramada, then at her house. “Do you need anything? Can I bring you anything? Firewood? Some palmetto for

that place where the wind shredded your ramada roof?”

She picked little bits of dough from her slim brown fingers. “I appreciate your offer, but I suspect that you didn’t come here because you were worried about my firewood supply.”

He settled back on his butt, rubbed his sun-browned shin, and looked around at the near houses. His expression had a slightly pained look as if he were trying to find the right words.

“Is it about your mother?” she asked. Eats Wood still lived at home. He had been notoriously hard to marry off. Despite the size of Sun Town, Eats Wood’s reputation preceded him. Few in the other clans considered him a likely candidate for marriage—even though Snapping Turtle Clan’s influence had grown like a north wind at winter solstice.

“She is fine, but thank you for asking.” He pressed his lips together, studying her with narrowed brown eyes. “It is said that you will very likely become our Clan Elder someday.”

“That day—if it comes, Eats Wood—is a long way off.”

“It is said that you had a chance to divorce Speaker Salamander.”

“Any woman has a chance to divorce, Cousin. That’s a little fact that I hope you keep in your head when and if you do marry.” She arched a challenging eyebrow.

He grinned sheepishly. “Yes, I know.” Then he sobered. “Why do you stay with him?”

“I have my reasons, Cousin. Among them, because of who he is.”

“He is a Speaker in name only. You could have—”

“I wasn’t referring to his title.”

“Most people think he is a fool, Cousin.”

She considered him frankly and lowered her voice. “They are wrong, Eats Wood. I may be speaking to emptiness, but I want you to listen to me. Do not underestimate Salamander. I tell you that as a kinsman.”

His round brown eyes didn’t register any comprehension. “He’s got that Swamp Panther woman for a wife. You could have anyone else you wanted.”

“He has his reasons for marrying her.”

“She was here before. She is the one his brother caught down at Ground Cherry Camp.”

“So?”

“Cousin, look what we did to her and her friends!” He leaned close. “You are part of his household, don’t you hear things about her? About what she’s after here?”

“You mean, does my husband trust her?”

“Yes.”

“Not completely.”

“She goes away every moon.”

“Of course she does. Think it through, Eats Wood. Would you want her here during her moon? Hmm? Bleeding where any man, yourself included, might step in it? No, I suspect you would have her gone, far away, where her woman’s blood won’t make you ill.”

“What’s wrong with the Women’s House? She can go there for her moon with all the rest.”

“Put yourself in her place. Would you want to be shut up in the men’s Society House in the middle of the Panther’s Bones? Would you want to be surrounded by their suspicious warriors for days? Would you want to hear them snicker at your expense?”

He stared suspiciously at her. “I’ll bet she meets with her Swamp Panther kin, what will you bet?”

“She has no friends here. If I were in her position, I would want to see kin, too.”

He seemed perplexed. “You don’t seem at all worried.”

“I will worry when I have reason to.” She gave him a sidelong look. “But why are you so interested in her?”

He spread his hands, trying to look casual.

“Uh-huh,” she answered. “One of these days, Cousin, you are going to be like Father Moon. Some woman will possess your thoughts and lead you into a mess you can’t find your way out of.”

“She’s dangerous,” he muttered uncomfortably. “You just watch, Cousin. She’s going to get you into trouble before she’s done here.”

Wind howled in the thatch, poking cold fingers through the gap where the roof overhung the walls. It made a soft whistle as it blew around the house. Gusts shook the structure, cracking the wattle and daub. This wasn’t a night to be out.

Salamander lay awake under the snug buffalo robe and stared up at the darkness. Anhinga cuddled next to him, her warm rump pressed against the angle of his hip and thigh. Cold air played patterns across his face, tickling loose strands of Anhinga’s hair against his cheeks.

Turning his head, he could hear the soft rattle as leaves blew past. From the flapping sounds, the palmetto matting that roofed his mother’s ramada was shredding and would have to be replaced.

His house shivered under a particularly hard blast. In his bones he could feel the storm’s strength as it blew down from the north.

He blinked, wishing he could sleep with Anhinga’s soundness. Instead, images flashed through his mind. Bits of the Dream that had awakened him replayed over and over. He had been flying, sailing across the sky on Owl wings. A black shadow had blotted the sun, and talons had ripped painfully through his back. In that instant he was falling, the ground spiraling as though rising to meet him.

Breath had frozen in his lungs, his throat locked. His stomach had lurched, weightless, falling, plummeting like a carved piece of hematite. The air rushing past had become the roar of the winter wind outside his house before he plunged headfirst into Sun Town’s earthen plaza. At the last instant he had jerked awake.

“What?” Anhinga had murmured, shifting on their narrow bed.

“Nothing. A Dream. Sleep.” He had patted her shoulder as she slipped her arm from across his chest and rolled onto her side facing the wall.

But he had lain there, awake, his heart pounding, the terrible image of falling still tingling in his blood, muscles, and bone. The sight of that green ground had been so real! The spreading arches of the clan grounds, the buildings casting shadows, couldn’t have been imagined. Even the pathways, beaten into the grass by countless bare feet, could be seen spreading out like veins.

With great care, he slipped out from under the heavy robe. Chill washed his sweat-clammy skin as he tied his breechcloth on and found a feather cloak to wrap around him. Moving the palmetto-mat door to one side, he stepped out into the gale.

Wind whipped his hair, half blinding him. Bits of sand and debris shot pinpricks into his skin. Turning, he pulled the cloak tight and walked straight into the teeth of the storm until he reached the third ridge. Counting houses, he hunched his way to the Serpent’s.

He huddled against the south wall, in the lee of the blast, and called, “Elder? It is Salamander. Are you awake?”

“I am now,” the reedy voice called. “Come.”

Salamander ducked into the wind, wrestled the wicker door aside, and replaced it behind him as he stepped into the cold darkness of the Serpent’s house. Here, at least, the gale was moderated to a gentler movement of air.

Wood clattered as the old man threw it atop the gleaming red-eyed coals in the central fire pit. Helped by the cool breeze, flames immediately leaped up. Their flickering yellow light showed the Serpent,

sitting naked on his bed, his flesh hanging in wrinkled folds, his flat face puffy with sleep. Gray hair stuck out like winter grass in all directions.

“What is it? Salamander? What brings you here? You are not ill are you?”

“No, Serpent. It was a Dream,” he explained as the old man seated himself and pulled his elkhide blanket around his shoulders. The fire shot yellow light, and Salamander glanced about the interior. The clay walls had been engraved with designs of interlocking owls, sitting foxes, panthers, and snakes. Above the old man’s bed a great bird had been carved into the daub, its wings and feet outspread, the beaked head turned sideways.

Bags of herbs hung from every rafter, their sides sooty from countless fires. A line of wooden and leather masks were propped along one bench, ritual faces that the Serpent adopted for healings and ceremonials. A pouch that Salamander knew contained stone sucking tubes, feather wands, and diamondback rattles rested by the old man’s swollen feet.

Other ceramic jars and small soapstone bowls held bits of mushrooms, dried nightshade, jimsonweed, gumweed, snakemaster root, dried hemp leaves, and other medicine plants. One big bowl was filled with bear fat as a base to mix his potions.

The old man listened to Salamander’s recounting of the Dream, nodding. As he spoke, Salamander realized that the old Serpent’s flesh seemed to be even thinner on his bones than it had been.

“Many Colored Crow is gaining in Power,” the Serpent said after Salamander finished. He ran a hand over his flat face, the action rearranging his wrinkles.

“What does it mean? Falling like that?” Salamander extended his hands to the fire and shivered at the warmth.

“It is a sign.” The Serpent pulled his elkhide close as another gust of wind shivered his house. “You are supposed to be frightened. Many Colored Crow is telling you that if you give up, go away, you will not have to be destroyed.”

Salamander studied his hands, black silhouettes against the flame. “I have started to relax, Elder. As fall came to the land and the leaves changed, my world began to take form.”

“And Anhinga?”

“She carries my child, but leaves with every full moon to pretend to pass her woman’s bleeding in seclusion. She uses that time to plot with Jaguar Hide.”

“That is very dangerous.”

He bowed his head. “I know.”

“Why do you not throw her out? You know she bears you no goodwill.”

“Masked Owl whispers that I will need her.”

“To achieve your death?”

Salamander shrugged. “I am not certain, but maybe. If I must die, Elder, to serve Masked Owl, and if Anhinga is to be the manner of it, then I accept that.”

“I, too, am dying.”

Salamander looked up, startled. “What?”

The old man pointed to his gaunt stomach. “I have a pain inside that only gets worse with the passing of the moon. Something evil is growing in my gut. When I squat to defecate, what comes out is half blood. It gets worse with the passing of days.”

A sinking sensation left Salamander shaken. “No, not you, my old friend. I need you! Without you, I am alone. You must take something! Do something. Surely some licorice root, or …”

The old man was shaking his head. “I’m afraid the something to which you refer has already been done. It is some spirit, some evil that is eating me. When I press, I can feel it. A hardness so painful it brings tears to my eyes. Probably something I picked up from someone I cleansed. Maybe I wasn’t careful enough with their vomit.”

“How long has this bothered you?”

“A moon. Maybe more.”

For what seemed an eternity, they sat in silence.

The Serpent asked, “What of your other wives?”

“Pine Drop missed her moon. She seems satisfied.”

“Indeed. I noticed that you haven’t come for more dogbane. Nor have I heard that she has been carrying on like a camp bitch anymore.”

“It was Mud Stalker and Sweet Root who put her up to it.”

“Umm. And Night Rain?”

“I would feed her plenty of dogbane if I could. The problem is that I can’t just put a pinch into the communal food bowl without harming Pine Drop as well.”

“There is talk. Deep Hunter has recalled Saw Back from Yellow Mud Camp. It is said that he did it to favor your youngest wife. Have you heard?”

“That Night Rain is coupling with him? Yes.” Salamander rubbed his hands together. “Pine Drop disapproves, but says nothing. That tells me that Night Rain has Mud Stalker’s approval to lock hips with Deep Hunter and his kin.” His lips tightened. “My young Night Rain has been learning new tricks. When she does

share her bed with me, she isn’t the same limp bundle of cloth I first married.”

“Deep Hunter and Mud Stalker make a strong alliance.” The Serpent bowed his head. “Moccasin Leaf seems to relish her new position as Clan Elder. I am sorry I could not bring your mother’s souls back. I fear they are too tied to the souls of the Dead.”

“Sometimes, Elder, we cannot win every battle. I do not understand why Power has left her demented. Perhaps it is part of the balance, part of the price I must pay.” Salamander sat back, some of the warmth returning to his body. “My enemies will not act yet. They are waiting, slowly turning their attention to each other.”

“Why do you not act against them?”

“Masked Owl once told me that my salvation lay in the things I knew, in being who I was. I watch, Elder. I study. It is for a reason that you named me Salamander.”

“But if the fox or eagle should catch you …”

“The ways of Power are not without risk, Elder.” Salamander smiled. “Since we last talked, I have watched the leaves turn and fall. The clans have returned from most of the distant camps, their bags full of acorns, walnuts, beechnuts, hazelnuts, goosefoot seeds, squash, knotweed seeds, and chinquapins. Canoe loads of fish have been dried and smoked, and the hunters have taken ducks, geese, pigeons, herons, and cranes. Deer are plentiful, and Trade has been good from the prairies, so buffalo and elk meat are plentiful. For the moment, bellies are full, and the clans are eyeing each other, trying to determine who has incurred the greatest obligation.”

“The winter solstice ceremonies are barely a moon away.” The Serpent rubbed his callused hands, a dullness to his eyes. “Have you given any more thought to following me?”

“Yes. My answer is the same. Bobcat must follow you—and for many reasons. I do not know the Songs, Elder. I barely know enough of the plants and rituals. I couldn’t follow you if I wanted to. I must serve Power in another way.”

“As your Spirit Helper deems.”

Salamander nodded, smiling. “You once asked me a question, Elder. You asked why the Great Mystery ripped the Earth from the Sky.”

“Ah, yes. I remember. Have you found the answer?”

“I think so. It was because before the Creation, everything was One. Everything was the same.”

“Ah!” The old man’s face lit with joy, the wrinkles on his face stretching. “What was wrong with that?”

“Being One is being nothing, Elder. The world wasn’t really Created until Sky and Earth were separated.”

“Why is that, Salamander?”

“If you are One, you cannot see. Cannot hear. The only sensation is of yourself. There is no ‘Other.’ The world had to be divided in order to see itself, in order to become itself. In the One, there is no beginning or end, no me or you. Only when we are separate can we inspect each other and learn the complexity and beauty of the universe. That was the lesson you were trying to teach me that night atop the Bird’s Head. That is why Sun Town is so important. It is here that all things come back together. North and South. East and West. Sky and Earth.”

Smiling gently, the old man nodded.

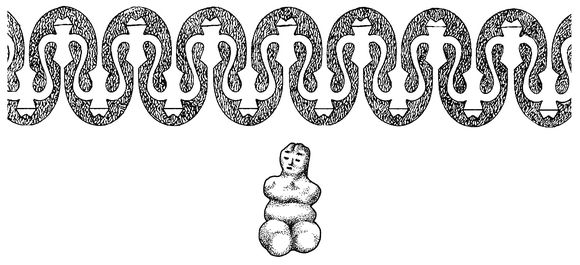

The fire popped and crackled, sending sparks toward the roof. Then the old man reached into a rabbit-hide sack and withdrew a small figurine. “Do you know what this is?” He handed it to Salamander.

The piece was smaller than his knotted fist, formed into the shape of a corpulent woman’s seated torso, breasts and buttocks pronounced, arms and legs but nubbins. The head depicted the center-parted hair of a married woman, her eyes and happy mouth mere slits. The nose had been pinched out of the face, almost beaklike.

“No.” Salamander turned it in the light. “I’ve never seen a charm like this before.”

The Serpent reached into his bag, retrieving yet another one, similar to the first, and handing it over. “Men usually don’t see these. Women ask for them. Take them. Bury one under Anhinga’s bed when she is not present. Bury the other under Pine Drop’s.”

“What do they do?” Salamander studied the two figurines in his hands.

“Any evil or illness that comes to sneak up your wife’s sheath to infect the infant will be fooled and will invade the clay charm instead.” He pointed his finger. “Now listen. This part is important. When your children are born, the charms must be dug up. This must be done immediately. When the afterbirth is passed, it must be rubbed over the charm to cleanse it. Then, and only then, you must bring the charm back here, to this house, and snap the head off.”

“Why?”

“The afterbirth feeds the evil, tricks it into thinking it is living in the baby. When you snap off the neck, you trap it inside the charm. It must be buried here because it came from here,” the old man

said. “From this earth, here, outside of this house. The Power must be returned to the place from which it came. Bury the pieces of the charm, Salamander, put them back where they came from. If you do not, the Earth Mother will become angry. The evil will fly back, angry at being deceived, and kill your child. Do you understand?”

“Yes, Elder.”

The Serpent closed his eyes, and breath caught in his frail chest. His expression twisted, neck bending as he tenderly placed his hands against his left side.

“Elder?”

A moment later, he blinked, and tears appeared at the corners of his eyes. “I need to lie down now, Salamander. Forgive me. I cannot think when it hurts like this.”

“Can I do anything for you?”

The old man nodded. “There, in the bowl with the fox on the side. That paste, it is made with ground jimsonweed seeds. Take that stick, there. That’s it. Dab just a little on the end. Thank you.”

The old man leaned back, taking the stick in trembling hands as he touched it to the tip of his tongue. “Things will be better now. Yes, better.”

Salamander placed the pale elkhide robe over the old man’s bony body, ensuring it was tucked tightly. “Sleep, Elder. I’m sorry I bothered you.”

“No. It’s fine.” He smiled wearily. “You will be the greatest of them, Salamander. If they don’t kill you first. Many Colored Crow is a Powerful enemy, but he will not take you himself.”

“Like he took my brother?”

The old man’s eyes flashed open, brown, penetrating, as if the pain had vanished in an instant. “What makes you think that? Your brother wasn’t killed by Many Colored Crow.”

“Then who? Who else could control the lightning?”

“Any of the Sky Beings,” the Serpent told him, voice low, as if he were sorry he’d said anything. “Now, go away. Let me sleep. Nothing else eases the pain.”