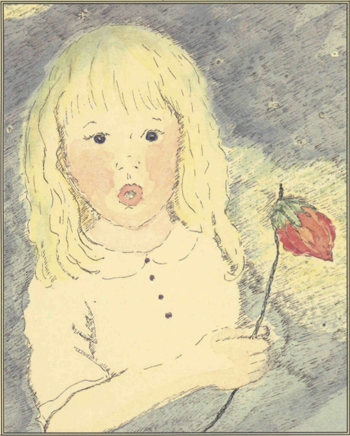

Jane Hogue says that her 11-year-old daughter Janna is fascinated with the garden. “She explores barns and haymows, along the fence rows and ditches, down garden paths, and among the herb beds,” she said. Janna reports home on any beautiful blossoms, unusual spider webs, flowers that are ready for cutting, ripe strawberries, and perfect hiding places.

Janna received a copy of Frances Hodgson Burnett’s Secret Garden and immediately fell in love. She is busily making plans for her very own secret garden this summer, a place where she can weave dreams, adventures and sunshine into a beautiful tapestry.

Jane and Jack Hogue believe that raising children and growing gardens have many similarities. Both need nurturing and care to grow and blossom. Their children are thriving and blooming under their special care—we could all learn from them!

Working in my garden at Heart’s Ease one day, I turned to greet an elderly lady. “Oh,” she said, her voice full of nostalgia, “this reminds me of my childhood in Nebraska.” I knew she must have some special memories to share. “Can you remember any special garden things you did as a child?” I asked.

She thought a moment then began a wonderful story: “We were poor and didn’t have lots of store-bought things. My favorite flower project was our summer playhouse—we didn’t have a regular playhouse, but one we planted every year.

“In early summer, my mother would wake us up with ‘Get up you sleepyheads, today’s the day!’ and we would get out of bed and pull on our clothes. We didn’t even want to eat breakfast, but she would make us sit down and take our time. It all just served to heighten the excitement. We couldn’t wait to get outside.

“Chores done, watering can and stick in tow, we would head outside and take time choosing the best, flattest, sunniest spot in our garden. Then the work would begin.

“Mother would use the stick to trace out a large rectangle, usually about 6 by 9 feet, leaving a small opening for a doorway. She would drag the stick along the ground and gouge out a trench a couple of inches deep. My little sister and brother would trail behind and drop in seeds. John would drop in a big, fat sunflower seed; daintily, my sister would tuck in a ‘Heavenly Blue’ morning glory seed. I would trudge along behind them lugging the huge tin watering can. I’d use my foot to knock the earth back over the seeds and then I’d give them a small drink of water.

“Every day one of us would have the chore of walking that rectangle of land and giving a drink of water to the sleeping seeds. We all hoped to be the one to discover the first awakening green heads that poked through the soil.

“Once the green of the sunflowers peeked through the earth, we became even more interested in our growing playhouse. Usually, we would each water the plot once a day. Soon the sunflowers were climbing skyward and the ‘Heavenly Blue’ morning glories were wrapping their tendrils around the stalk and heading upward too.

Sunflower House Top View

“I don’t know how long it took before the sunflowers were at least twice as tall as us kids, but soon they were and Mother would come out with a big roll of used string we had saved up through the winter. ‘John, you fetch the ladder and we’ll get your roof going today,’ Mother would say. My brother would drag out the big ladder and Mother would tie string to the top of one sunflower’s neck. She would lace the string across that rectangle, back and forth, back and forth, ‘til all we could see was a spider web of string against the blue Nebraska sky.

“In a matter of days, the Heavenly Blues would start journeying across the web, and soon the string was invisible. Looking up, all you could see was the gold of the sunflower faces, the green of all the leaves and like patches of the sky itself, the blue of those morning glories. I’ll tell you there was nothing like crawling through the door of that playhouse and lying on the ground looking up through that incredible lacework of vines and flowers. I guess you could say that I spent the best days of my childhood playing, dreaming, and sleeping in that little shelter.”

How do you go about furnishing a house so special? Surely you cannot go to a store and buy anything that will fit properly into such a home.

The children searched fields and woods and found everything they needed. Their mother did not have to teach them to do this; they just knew, instinctively, what was right for their playhouse. What they chose was what their mother and father, grandmother and grandfather had used before them.

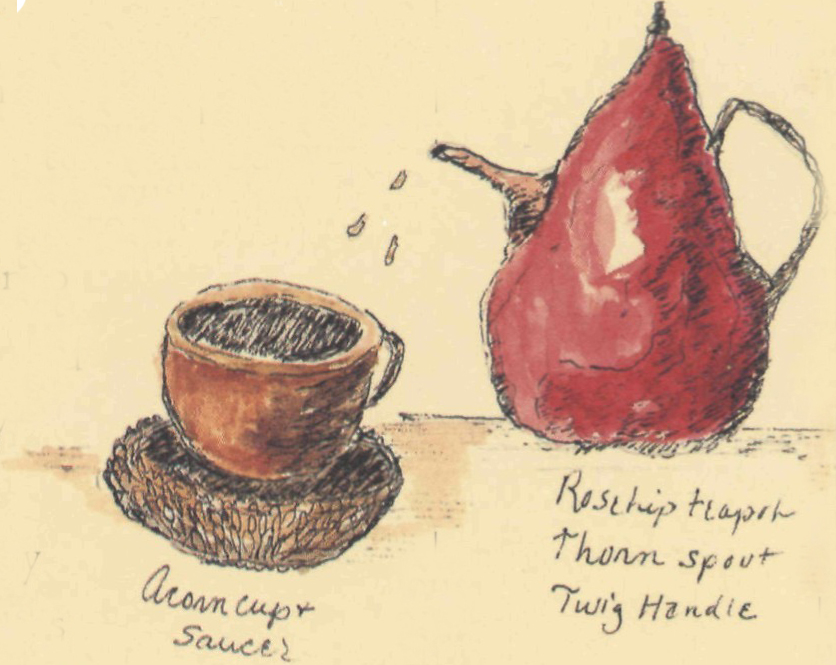

For a table, they rolled in a large, flat rock. Perfect chairs came from the woodpile—short, fat stumps. Doll beds were made of corn husks and down-stuffed milkweed pods. For carpets, moss and lichens; for coverlets, great big leaves (sycamores were soft, but woolly lamb’s ears and old-fashioned mullein were the best). Dinnerware was not a problem—round honesty plant pods were dishes, acorns and caps made cups and saucers, a plump, red rosehip poked with a thorn became a teapot with a spout.

Filarees were scissors, wild walnut halves were the porridge bowls (look at the heart inside them), beech leaves were napkins, and a burr-basket (from burdock) filled with miniature wildflowers sat in the middle of the rock-table. The garden was an endless toy store.

At night, the children ran barefoot through the grass catching fireflies. Gently, so as not to injure the fragile, flickering lights, they tucked them into the blossoms of hollyhocks and knit the edges together with a long twig. Some of the hollyhock-firefly lanterns were hung inside the sunflower house. Others were used in fairy-like processionals through the moist darkness of the garden.

Children love a place of their own to use as a hide-out. I once saw this wonderful teepee—a perfect place for summer play. Here’s how to make it: Set four to six poles in the ground at an angle and bring them together at the top, securely lashing them with some heavy twine to form a teepee shape. Run twine roughly around the teepee to form a ladder for scarlet runner beans or showy painted lady beans (both flowers and pods are edible) and varieties of gourds. Plant seeds all around the base of the teepee. As the vines begin to reach upward, the children will be fascinated with the climbing process and the searching tendrils. (Show them how some vines always wind clockwise and others always wind counterclockwise).

As the teepee fills in, it becomes a secluded, dream and play-inspiring hide-out. An added treat is that the children can use the gourds they have grown to make bird houses, bowls, nests, toys—the possibilities are endless, and they grew them themselves!

When I was a child growing up in the fragrant, golden hills of southern California, one of my favorite play areas was the wooden sandbox under our gnarled apricot tree. Flanking the sandbox were hollyhocks, carnations, iris, and rainbows of sweet peas—a palette of color for building castles.

Early dew-laced mornings would find me outside picking bouquets of blossoms to use in my construction project for the day. The night-moist sand was easy to mold and as I built, I studded the sides and roof with a mosaic of blossoms. Tips of bushes and ends of tree branches became a forest surrounding my creation. Tiny clumps of moss lined the path leading to the doorway—perfect bushes.

As the day progressed, friends joined in and helped add rooms and designs of flowers to the castle walls and pathways. At dusk, the last warning call came from our mothers—time to go inside now, or else! Deliberately and gleefully, we leapt into the center of our castle—every last vestige of our creation vanished. We felt no remorse, we knew our summer days stretched endlessly ahead. There would be other castles.

“That delightful thing, a sand-pit: it is a place of everlasting joy when one is small, and even when one is growing fairly biggish. We dig out arched recesses to sit in, and we build castles and all sorts of houses with the heap of loose sand at the bottom…And then we get some flowers and make quite a pretty garden round the house.”

Gertrude Jekyll,

from “Children and Gardens”, CountryLife, 1908.

Ricky Beauclaire and I were the neighborhood whirlwinds. We were up in every tree, under every bush, and behind every rock. If there was trouble to be found, we found it (or maybe we caused it!).

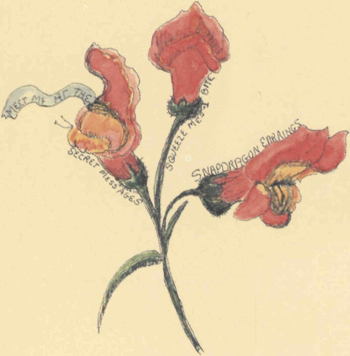

We were inseparable, but when we were forced to be apart we found ways to communicate. Secret letters were tucked into a hole in our favorite old apricot tree and when Jackie Wingo found our hiding place we mystified him by writing with lemon juice “invisible ink”. We put tiny, tiny messages inside the closed mouths of snapdragons, scratched letters onto mulberry leaves, and left cryptic trails of leaf messages on the sidewalk (which usually blew away before they were found).

Write a secret message with lemon juice or milk. When it is dry the words are invisible. To read the message, press the paper with a warm iron. The words come back like magic!

A recurring theme of faeries and woodlore cropped up in dozens of letters and reminiscences I received from throughout the country. And what would my own childhood have been without the secret hideaway of boughs in Grandmother’s garden?

Dorothy Fitzcharles Weber, author of Artistry in Avian Abodes, wrote me, “Many of the nature crafts and lore I learned from scouting I practiced with my own children and then grandchildren at Crystal Lake in Maine.

“There were white birch trees, many unusual mosses, pink lady’s slippers, curious rocks, hemlock cones, ferns and a multitude of natural materials.

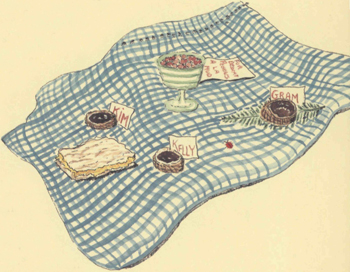

“When Kim and Kelly were little girls we would have wonderful tea parties. The place-mats were fern fronds, acorn cups were doll-sized tea cups, and then a choice of birchbark sandwiches filled with buttercup spread and tea brewed from soldier moss. Dessert was often pebbles à la mud.”

From many miles away came this note from Susan Jones Sprengnether, who grew up in St. Louis, Missouri.

“I clearly remember making homey places for the faeries who lived in the woods. These places were snuggled in amongst the roots of trees and mostly in mossy areas. We made dishes of acorn tops, cradles of walnut shells, leaves were cots or hammocks, and tables were made of twigs lashed together.”

And from many, many years away:

“It was to please the faeries that, long before I had heard of naturalizing bulbs or knew the name and the fame of W. Robinson, I planted a ring of white crocuses in the grass round the bole of the wych elm one November. When the white circle appeared in spring, Mother said, ‘Who put those crocuses in the grass? It must have been you, Nan.’ I hung my head, expecting a wigging, but Mother smiled and said, ‘Your grandmother used to do that in Bethnal Greens in 1820. What made you do it?’ But I did not tell her, nor anyone else, that it was to please the faeries.”