THE WELLING UP OF

CONSCIOUSNESS

How thin and insecure is that little beach of white sand we call consciousness. I’ve always known that in my writing it is the dark troubled sea of which I know nothing, save its presence, that carried me.

Athol Fugard

It’s time to tackle consciousness. Up to now I have felt the need, every so often, to point out that much of our body-brain intelligence proceeds perfectly well without conscious awareness. All kinds of very clever and intricate things are going on in us, underpinning our behaviour and our experience, of which we are not aware. Indeed, consciousness sometimes gets in the way of our expertise, as when we become ‘self-conscious’ and ‘awkward’, losing the subtle grace of what we were doing or saying before. A child carrying a full cup of tea is more likely to spill it if you keep telling her to ‘watch what you are doing’. Yet awareness does seem to make a difference, often for the better. It is certainly of the utmost importance to the Cartesian notion of intelligence, where consciousness is seen as the theatre of the mind, the floodlit stage on which our highest thoughts strut their stuff.1

So we need to ask: where does consciousness come from; when does consciousness accompany somatic activity; what is it good for; and when and why are we sometimes better off without it? Let me be clear. I am not going to attempt what philosophers like to call ‘the hard problem of consciousness’ – what consciousness is, in its own right, and why we have conscious experience at all. I have no idea why this ‘emergent property’ of the human system evolved, any more than I know why a whole lot of H2O molecules, when they get together in a certain way, produce the emergent property called ‘wet’. For the moment, I’m happy to settle for, ‘Well, they just do’. The other questions are quite exciting enough for me to be going on with.

Metaphors for consciousness

As with mathematics, the place we need to start, to get an embodied handle on consciousness, is with metaphor. All attempts to discuss consciousness, even very sophisticated ones such as those of philosophers or cognitive scientists, spring from a metaphor – usually one that is very concrete. Whether they are explicit or not, these metaphors betray themselves by the language that is used to talk about consciousness. For some people, as I have just said, consciousness is a kind of brightly lit chamber or theatrical stage in the mind, and conscious experience is all that happens to be ‘on-stage’ at any moment. Some cognitive psychologists have associated this ‘chamber of consciousness’ with constructs such as Working Memory, or the Central Executive, in which case the stage becomes a ‘workshop’ where processes are applied to the contents.2 This metaphor invites one to think about alternative ‘dark’ regions of the mental theatre where the same contents (props, actors and so on) may exist, and may carry on functioning, but out of sight of the ‘viewer’ – the ‘I’ – who is some combination of stage director and audience member.

If the actors start to behave badly, the ‘I’ can also act as a censor, banishing (‘repressing’) lewd or disgraceful performances from appearing on the stage. The Freudian image of the ‘subconscious’ is of dangerous material, incarcerated in a particularly dark place in the mind, which constantly has to be kept out of sight by such a censor. Sometimes this material seems to be ‘alive’ – to have a will of its own – constantly threatening to erupt unbidden into consciousness, grabbing the mind’s steering wheel and coming out with an embarrassing ‘Freudian slip’.

Alternatively, consciousness has been seen as a screen – sometimes a display panel or ‘dashboard’ – in the mind, on which certain information, the contents of conscious experience, can be posted. The viewer of this information might again be the first-person ‘I’, or, in the case of Bernard Barrs’ ‘global workspace theory’,3 might be other processing modules in the mind, not necessarily conscious, which can pick up the posted information and contribute their own expertise or perspective to ongoing problem-solving. The ‘I’ could be seen as an operational manager, watching the activity on the screen and pressing keys to determine future processing, while the chips and processors on the computer’s motherboard constitute a kind of ‘cognitive unconscious’. Sometimes this metaphor has been used to make a strong distinction between the objects in mental storage (‘declarative memory’ or ‘knowledge’, capable of being brought into consciousness), and the processes and programs that can be applied to that database (called ‘procedural memory’, usually not conscious).

Or again, conscious awareness could be seen as a roving spotlight that sequentially highlights different contents in memory. On this image, mental contents are not moved around between different locations, some of which are conscious and some not, but are illuminated in situ. Sometimes this illumination is seen as a form of neural activation – people often talk about different parts of the brain ‘lighting up’ – and the activation itself may be capable of altering the activated representation. (Animals in a forest at night behave differently when you shine your spotlight on them from the way they behave in the dark.) This metaphor, often used in the context of creativity, allows the source of illumination to be narrow and focused, or diffused, more all-encompassing, but perhaps of a lower level of intensity. A focusing mechanism allows you to ‘zoom in’ on a tight, bright train of thought, or you can ‘space out’ and look into your inner world more dimly but more synoptically.

Each of these metaphors leads us off in a different direction for thinking about consciousness. Many of them see consciousness as a special ‘place’ where the contents of the mind can be inspected or ‘worked on’. Yet there is no evidence that there are real locations in the brain that correspond to the Central Executive or the Global Workspace, to which passive ‘contents’ get sent for processing, like books being recalled from the stacks of a university library and placed on a student’s desk. And many of these images also rely on a mysterious agent who does the calling-up, inspecting and assembly. Who is wielding the spotlight? Who is guarding the cellar door? They cannot help us very much here, because they smuggle in the Cartesian split between Mind (the active intelligence) and Body (the passive storehouse of ‘long-term memory’).4 They beg the very question we want to explore.

I am going to offer two alternative metaphors for consciousness that I will call ‘unfurling’ and ‘welling up’. They are similar, but emphasise slightly different aspects of the underlying view I want to develop, so I shall interweave them as I go along. Let’s start with unfurling. Imagine the growth of a plant, a fern, say, or perhaps a rose. The fern starts from an imperceptible spore in the ground, and then grows over time into a large, visible, highly differentiated mass of fronds. Let’s say the spore is the original ‘fertilised ovum’ of an intention, an urge or a concern that is born deep down in the visceral, emotional core of the body. Over time, that motivational seed, like the fern, unfurls into a complex physiological, behavioural – and sometimes conscious – expression of that germ of an idea. Take a time-lapse film of the growing fern and speed it up, so that the whole process now takes a split second. It will be hard to spot the stages of growth. It will look as if one moment there was no fern, and then, suddenly, there is a fully formed fern-thought, or action, or emotion. In this metaphor, there is a core sense of a self-organising, dynamic process of development. There is no fully formed ‘unconscious thought’ that merely has to leap on to the stage, or on to which we can shine a light.

This perspective on the formation of ideas, acts and experiences was originally dubbed ‘microgenesis’ by Heinz Werner in 1956.5 Werner saw the generation of a thought, for example, not as a jigsaw-like process of assembling word-meanings according to syntactic rules (the dominant cognitivist image at the time), but as a process of rapid evolution from a subcortical glimmer of meaning into an elaborated complex of sensory and motor activations across the brain as a whole, and thence back again to the muscles and the viscera of the body.6

Nothing in the image of unfurling yet suggests when or how, or even whether, consciousness appears. Very often the seed – the embryonic concern, we might call it – germinates into an action rapidly and effortlessly without any conscious awareness. For example, we may be walking down the pavement deep in conversation with a friend, completely oblivious to the subtle manoeuvring of our bodies as they chart an intricate trajectory between the oncoming pedestrians. Or we could be eating a bowl of cornflakes while totally engrossed in a movie. If we wanted to add consciousness to the unfurling metaphor, we could swap the fern for the rose bush, and call the growth of the foliage ‘unconscious’, and the blooming of the white flower ‘conscious experience’. (This of course explains nothing by itself, but may direct us, as metaphors often do, towards more compelling considerations.)

To capture the experiential side of microgenesis more fully, I will make use of the other metaphor, welling up; as, for example, when we well up with emotion. Actually, welling up is a deeply embodied metaphor; many of our experiences of the body have this developmental quality. A sneeze and an orgasm are capable of being noticed as they gather muscular strength and patterning. But so do a bubble of laughter (that we may struggle to contain) and the feeling of being moved to tears. Some of our more psychologically tinged experiences also display at least aspects of their unfurling in consciousness. They start, if we are being attentive, vague, hazy and slight, and grow in shape, definition and urgency.

Most of us are familiar with this experience of ‘welling up’ – occasionally. But my more radical suggestion is that these special moments are actually prototypical of our conscious experience as a whole. All our thoughts and sensations well up from visceral and unconscious origins in the same way, though we may not notice the unfurling. Benny Shanon sums up this integrated, embodied view of the mind, using a different set of metaphorical terms, like this:

Fully-fledged cognitive patterns are generated out of a substrate which is qualitatively different … [These substrates] are not cognitive or mental in the sense that manifest patterns are. The process of this generation is one of differentiation and fixation, whereby patterns with well-defined structural properties are created out of a substrate lacking such properties … I call the process of this generation crystallization, and I maintain that this is one of the fundamental operational features of the human cognitive system … [Conscious] structures are not the basis for mental activity but rather the products of such activity.7

That last sentence captures more formally the essence of what I am trying to say. Shanon’s ‘substrate’ of conscious thought is the bodily/emotional core of meanings, values and intentions that I have been talking about. These somatic stirrings are as different from conscious thoughts as the fibrous roots of a fern are from the exuberant intricacy of its fronds.

The welling up of gesture and thought

Everything is the way it is because it got that way.

D’Arcy Thompson

Let me bring some evidence to bear on this metaphorical proposition. If the ‘unfurling fern’ view is right, then we should see the original seed differentiating into different ‘branches’ as the unfurling takes place. For example, something we might eventually say, and all the non-verbal gestures that accompany it, may well stem from a common embryonic concern, and carry different aspects of the original meaning or intention. Our ‘utterance’ is the whole fern, not just one particular frond. Over many years of painstaking research, psycholinguist David McNeill at the University of Chicago has demonstrated that this is exactly what happens when we are trying to communicate.

His research focuses on the relationship between what we say – for example, when we are describing a cartoon we have just watched to a third party – and the hand gestures that spontaneously accompany the speech. Through detailed analysis of videotapes, McNeill and his collaborators have discovered that speech and gesture do indeed emerge from the same root, and carry complementary aspects of the meaning we want to convey. For example, describing a scene, one observer said, ‘Sylvester was in the Bird Watchers’ Society building, and Tweetie was in the Broken Arms Hotel …’ As she referred to Sylvester she gestured to her right-hand side, and as she referred to Tweetie she gestured to her left, indicating that the two locations were on opposite sides of the street. A few seconds later, she reported that ‘He then ran across the street’, and gestured to her right as she did so – indicating that it was Sylvester who crossed the street, not Tweetie. Speech and gesture were woven together seamlessly – and unconsciously – in order to resolve the potential ambiguity of the pronoun ‘he’.

We might imagine – if we could slow the ‘movie’ of our own experience down sufficiently – that we might catch the germ of the desire to communicate something as it begins to stir deep in the body-brain. It might involve a need for approval or a desire to impress – to want to be a ‘good subject’, in McNeill’s experiment – or a wish to convey involvement and amusement in the cartoon, or a dozen other intentions. When I say to my wife, ‘I think the front lawn needs cutting’, I can trace the source of that casual comment back to a small archaic tremor of potential concern about being disapproved of by meticulous neighbours. When she says to me, ‘Shall we go for a walk if it’s nice tomorrow?’ I can, I fancy, hear a faint echo of anxiety about my health and the sedentary nature of my work.

The broad structure of these fronds of communication is determined by the genetic programmes that shape our bodies. The actual expression of these genetic guidelines, though, is powerfully modulated by the accidents of our experience. So the fine details of how an embryonic intention unfurls are heavily experience-dependent. Synaptic connections are changed and chemical responses throughout the body altered by learning, so the pathways along which meanings unfold are individual and variable. At the risk of creating metaphorical overload: a gathering tide of activation flooding through the body is shaped by the channels and contours that thousands of previous tides have sculpted and left behind.

As we saw in earlier chapters, some of these ripples will cause visceral and autonomic ramifications: blood pressure and heart rate might go up, respiration volume might become shallower, background processes of digestion might be inhibited, hormones such as adrenaline or cortisol might be released into the bloodstream. All of these changes will be signalled to the brain and will alter levels of arousal, as well as the focus of attention (what we are on the lookout for) and the memory contents that are recruited into the unfolding meaning. The brain alerts muscle groups for the kinds of action that might be required, and facial expression and patterns of body tension are altered accordingly. Some of these muscular changes might involve coordinated patterning of throat, mouth and lips, at the same time as the lungs are expelling air in synchronised bursts – resulting in the utterance of a sentence or a sigh. And some more muscular activity might result in simultaneous movements in shoulders and arms that produce gestures which disambiguate or augment the meaning of the utterance.

We might call these the four major fronds of the developing ‘fern’ of experience. One branch elaborates internal, ‘interoceptive’ body states: visceral, hormonal, immunological and neural. A second alters the direction and acuity of incoming sensation, via modulation of the ‘exteroceptive’ perceptual systems. A third branch begins to ready muscle groups for direct action. And the fourth branch may head in the direction of linguistic and other kinds of symbolic output such as gestures. And, as the fronds of the fern remain connected at the heart of the plant, so all of these remain functionally looped together in the body-brain.

For example, suppose you are one of the participants in McNeill’s study. The seed of your desire to retell the story of the cartoon fires up memories and their emotional concomitants. These then cause your voice quality to intensify, a chuckle to form in your chest and the corners of your mouth to arch upwards. At the same time, the internal stirrings begin to activate appropriate patterns of words. The right muscles are recruited to shape your voice box and expel air to make the right sounds. And you establish eye contact with the listener in order to judge whether you are being successful in conveying the meaning and the feeling that you intend. Your arms and hands begin to form gestures that carry other aspects of the felt meaning you want to convey. A whole-body state fans out from the originating impulse, unfolding into an intricate, evanescent pattern of neural, muscular and hormonal events.

It has been shown that children’s arm movements can actually convey a more creative part of their overall understanding than their tongues or pens (or iPad screens). As they talk, children naturally gesticulate, and their gestures carry part of the meaning of what they are trying to say. One classic test of cognitive development is children’s understanding of what is called ‘conservation of volume’. If water in a tall thin beaker is poured carefully into a short fat one, the appearance of the water is different but its volume stays the same. Younger children are unable to escape the appearance and say that the ‘amount’ of water has changed.

If children are made to sit on their hands while they are talking about this phenomenon, they appear to be at this lower level of understanding. The unfurling of their understanding is hampered when they are deprived of gesture. Careful analysis has shown that children who, judging by their verbal explanations, are not quite at the higher level nevertheless show through their gestures that they are in fact aware of the conservation of volume. (They might cup their hands and move them from right to left, as if physically transferring the water, without changing the size of the ‘cup’, for example.) Susan Goldin-Meadow, the author of these studies, suggests that gesture is able to express more creative insight than the more conservative verbal ‘frond’ is willing to venture. What we say is judged more harshly than the way we move our hands, so gesture takes advantage of the slacker criteria to try out newer, more tentative ways of looking at the world.8

This close association between language and gesture also receives support from studies of brain organisation. As we saw earlier, Broca’s area – a brain region that has a lot to do with language production – lies next to the part of the brain that controls hand movements, suggesting that spoken language itself piggybacked on an earlier system of communication through gestures. According to one suggestion, our early ancestors first developed a kind of manual sign language, which gradually became augmented with characteristic vocalisations. As the vocal tract evolved to become more sophisticated, and the muscular control of tongue, mouth cavity, throat and breathing became more refined, so speech began to run ahead of gesture, and eventually became the dominant partner.

As the germ of an idea evolves into a linguistic utterance (or a written or ‘signed’ sentence), all kinds of syntactic and semantic considerations come into play. Through spreading activation in the loops of the body-mind, the unfurling idea starts to recruit candidate words and syntactic frames to carry the intended meaning. But it could be that no readily available words or frames are capable of accurately conveying the underlying intention, so, if the utterance is to proceed, some of the nuances and subtleties of the meaning may be lost in transcription, and what eventually comes out is only an approximation – perhaps a crude approximation – to what was intended. The horticultural term espalier refers to the process of training a plant – often a fruit tree – into a particular shape as it grows, through selectively pruning offshoots and tying other shoots to a frame that directs their growth. Language acts as a kind of espalier for the meanings that are germinating within the body-mind.

One kind of ‘training’ that happens to the embryonic intention is so common that it is rarely noticed. It involves the linguistic necessity, present in many languages, to insert references to a kind of ‘self’.9 Instead of just experiencing a thought, perhaps ‘Is the cat in the bedroom?’, we say ‘I wonder if the cat is in the bedroom’. Added to the thought is a somewhat gratuitous wonderer – just as when we say ‘It is raining’, there is no ‘it’ that is doing something called raining. ‘I’, like ‘it’, is a convention. (Or: ‘I’ is like a contour line on a map. It is a symbol that has no referent in the real world. It is not necessary to worry about tripping over the contour lines as you climb the hill.)10

Over time, as a child learns to use the dummy word ‘I’ correctly and fluently – not just ‘I fell’ or ‘I ate’, but the more puzzling ‘I saw’, ‘I tried’, ‘I decided’ and so on – it comes to seem that ‘I’ does indeed betoken some kind of ever-present ghostly observer, instigator, manager, editor or narrator lurking behind appearances. We get used to adding this ghostly espalier to each meaning as it unfurls. Eventually it appears self-evident to us that there is a (real, albeit spectral) observer who is capable of watching thoughts and experiences as they appear in and disappear from consciousness, and a real inner agent who does all the intelligent thinking and deciding. The Chief Executive of the mind, so central to the Cartesian view, turns out to be a linguistic convention rather than a potent force. The actual business of thinking is embedded in the process of unfurling; it is a function of the whole dynamic body-brain system, not of any mysterious Fat Controller of the mind.

But ‘I’ is not only redundant (as an internal agent); it also has the ability to make trouble. In daily life, the assumption that ‘I’ refers to a real inner entity can make self-critical judgements feel both more serious and more ‘sticky’. For example, in a linguistic construction, such as ‘I tried but failed’, there is apparently some thing (or some one) to which the judgement can adhere, and which is therefore obliged to feel culpable for the ‘failure’. Unnecessary depression and anxiety may ensue. Various kinds of therapeutic procedure, such as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, encourage people to observe the arising of thoughts such as ‘I’m a failure’ simply as a welling-up rather than as a valid judgement.11

Habits of attention

The process of welling up can take quite different time courses. Sometimes it takes only a fraction of a second, in which case it is very difficult to catch the unfurling as it happens. And sometimes the development of a germ of an idea into a communicable train of thought takes seconds, or minutes, or even longer. We may have to ‘um’ and ‘er’ while we wait for the mot juste to come to mind. Sometimes the unfurling is blocked, as when our brain refuses to come up with the name of a dear friend when we are having a ‘senior moment’. In many stories of creative insight, the solution to a problem hangs elusively just out of our grasp for months or years, until exactly the right set of triggers comes together and the answer is finally ‘propelled into consciousness’.12

However, overlaid on these different time-scales there may be habits of attention that make us more or less sensitive to the unfolding dynamics within. We may develop a generalised habit of not paying attention to the early stages of the unfurling so that, whatever its intrinsic time-course, we do not become consciously aware of what is welling up until late in its development. We come habitually to notice aspects of experience that are already well formed and elaborated, but do not notice their hazier precursors. Thus, instead of noticing the gradual clarification and differentiation of a thought or a feeling, we experience our own experience in terms of a step-wise distinction between things that are not conscious and those that are. They appear to ‘pop into’ our minds – or even, in a magnificent sleight of hand, to spring, fully formed, out of the mouth of the ‘inner I’. Thus – referring back to the earlier discussion about different metaphors for consciousness – what looks like a structural separation between conscious and unconscious can actually be a reflection of an acquired cognitive habit. We see a sharp distinction, but only because we are inattentive to the gradient that leads from unconscious to conscious.

We might also develop a habit of speeding up the unfurling process itself by drawing on the body-mind’s power to anticipate its own states. We know that our embodied system is capable of registering regularities in its own processing, and is therefore able to predict (with greater or lesser accuracy and/or confidence) what mental states are about to happen, on the basis of what mental states are already happening.13 This ability to anticipate states of our own mind makes it possible for us to take short cuts in unfurling, and leap to conclusions about what probably or usually follows the current state. To use our earlier prosaic example, a glimpse of what looks like Timmy’s tail disappearing round the corner of the house leads us to expect, were we to run and peek round the corner, that we will see the whole cat; but if we are lazy, or it really doesn’t matter that much, we can just assume it is (the whole) Timmy without bothering to check.

When we have to respond fast, taking such short cuts can be advantageous: it can even save our lives. But if leaping to conclusions becomes habitual, we are likely to miss detail and novelty. We construct our own world based not on the unprecedented particularities of the moment, but on what is normal and expected. Thus we can come to see in terms of faint, familiar stereotypes and generalisations rather than the vivid, complex individuality of what is actually present. (We experience a shadowy stand-in for Timmy. Had we checked, we might have seen that it was in fact an entirely different cat for which, we have just read in the local paper, a distraught owner has offered a substantial reward.) In effect we are trading vitality and inquisitiveness for normality and predictability.

Going too far in this labour-saving, top-down direction doesn’t just make life duller; it obviously incurs risks and costs. We might try to make the world conform to our expectations, and thus persist in applying methods of thinking and acting that worked once but are not, in a new situation, appropriate or effective. (Applicants for jobs at Google are often asked if they have a track record of success in their field. Those who boldly say yes are unlikely to be hired, because experience has taught Google that such self-confidence often leads people to try to replicate those successes by forcing new predicaments to fit old patterns; whereas Google is interested in people who can think from scratch and ‘flounder intelligently’ in the face of quite new challenges.)14

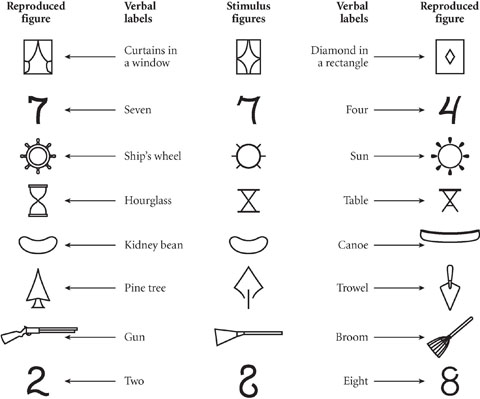

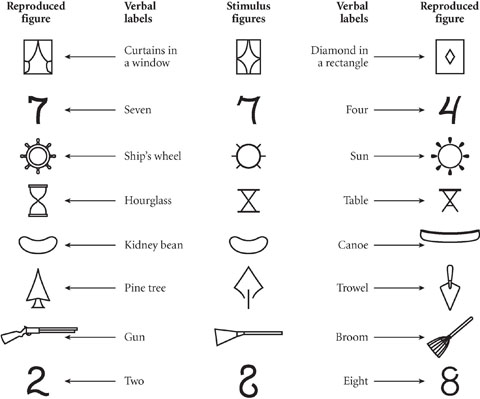

Language can certainly exacerbate this problem. There are many studies showing how a verbal label often leads to a kind of ‘functional fixedness’ in which alternative ways of looking at or categorising an object are rendered invisible by the label. In one classic study, researchers showed people ambiguous pictures with one of two suggestive verbal labels, e.g. ‘dumb-bells’ vs. ‘spectacles’. When participants were asked to draw the shapes from memory, it was found that the labels markedly skewed what they thought they had seen (as in Figure 10).15 This is one way in which creativity is reduced by leaping to conclusions. Creativity also suffers in other ways. We can become deaf to our own inklings and hunches, which recent research has shown are vital aspects of creativity. Being able to access and tolerate what some researchers refer to as ‘low ego-control’ or ‘low arousal’ mental states – those that are uncertain, provisional, ambiguous or vague – is demonstrably conducive to creative insight. These hazier experiences are at an earlier stage in their unfurling. They may be carrying the undifferentiated seeds of a new thought. Rushing the unfurling, forcing the hazy intuition into more familiar tracks, may well sacrifice the latent insight.16

The process of unfurling can be slowed down as well as speeded up. As we saw earlier, the process of checking candidate actions or utterances for accuracy and completeness may be subject to strategic control by those inhibitory frontal lobes. We can allow the ‘stream of consciousness’ to flow, or we can monitor and edit more carefully. When speaking a foreign language, for example, some people may dive in and ‘give it their best shot’ (especially in convivial company or after a drink or two), while on other occasions (or if they are temperamentally more cautious) they may self-monitor to the point of becoming tongue-tied.17 When a possible thing to say is being held back for checking, the motor programmes for producing the speech can be run ‘off-line’. That is, the incipient muscle movements for saying it can be run in a muted way that produces internal ‘thought versions’ which can be checked and edited. The eventual utterance will likely be more correct, but there is also a strong possibility that the conversation will have moved on, and the well-honed comment just won’t be relevant (or funny) any more.

Fig. 10 How language affects memory. Based on Carmichael, Hogan and Walter’s 1937 experiment.

The emergence of consciousness

As I have said, none of this unfurling is originally or necessarily conscious. Often the major frond involves only unreflective action. But, in the course of their welling up, different kinds of somatic events and patterns may be produced that do cause a conscious experience to occur. Such experiences come in a variety of forms. One is the perceptual world of sights, sounds and so on, which we interpret as a 360-degree wraparound backdrop to all our actions. Then there are more or less clear bodily sensations, feelings, emotions and moods. There are expectations, premonitions and intentions: feelings of readiness or anticipation; the feeling that we know something before we can recall it. There is a whole range of inklings, hunches, promptings and other kinds of intuition. There are verbal or symbolic thoughts, as well as internal sensory and muscular images. And there are ‘memories’ (images that come tagged as recollections of past events) and ‘fantasies’ (images that come tagged as possible or probable future events).

Consciousness varies not just in contents but in its quality. If what is welling up starts to turn into a conscious welling up, it can do so not only in varying forms but with varying degrees of clarity and intensity. Sometimes there might only be glimmerings of awareness: the haziest and faintest of apprehensions. Sometimes we are not even sure if we are feeling anything. Sometimes we know that we are feeling something, but can’t yet pin it down. Sometimes these inner works-in-progress unfurl further, so that what was hazy begins to take a clearer, more differentiated form. Yet sometimes insights, emotions or thoughts burst into consciousness with the utmost force, precision and/or certainty. And as I discussed earlier, these stages of unfurling can be further muddied by our own habits of attention. Some people can tune into the faintest signals from their bodies; others don’t seem able to feel it even when they are, to anyone else, visibly fearful or angry.

*****

All of these varieties of conscious experience constitute what we might call complementary ‘ways of knowing’. Each of them reflects something of what is going on in the interior. Each of them is useful, and each of them has flaws. However, on the Cartesian model, only disciplined trains of thought count as proper ‘thinking’, and only the conclusions of such trains, their logically arrived at termini, as ‘knowledge’. But we know all too well how stupid logic can be. After Queen Elizabeth II had wondered aloud how economists could have failed to foresee the credit crunch, an eminent group of them sent her an explanation. They wrote: ‘In summary, Your Majesty, the failure to foresee the timing, extent and severity of the crisis and to head it off, while it had many causes, was principally a failure of the collective imagination of many bright people, both in this country and internationally, to understand the risks to the system as a whole.’18 Imagination failed because the possibility of the crash was not part of the economic logic they were using. Logic can handle only a small number of well-defined factors at a time, so to think logically, we have to shrink the real, messy, confusing world to accommodate that constraint – and in doing so, often lose much of its vital richness and significance. It’s Garbage In, Garbage Out, however logical you are.

If logic has weaknesses as well as strengths, the other ways of knowing have a value that counterbalances their own shortcomings. Physical promptings and intuitions, for example, are not always reliable, but there are times when they can inform our decision for the better. ‘By the pricking of my thumbs, something wicked this way comes,’ intoned the witch in Macbeth, and we now know that our knowledge banks do sometimes speak to us in somatic ways. International financier George Soros takes account of his lower back pain when making a financial decision. Remember it is the physical arousal of the skin that is the first signal of learning in Damasio’s Iowa gambling task. Intuition and fantasy are of proven value and importance in all kinds of intelligent endeavours, from Nobel Prize-winning science to poetry-writing to preparing for elite sports. (Jack Nicklaus famously said: ‘When I hit a golf ball, [first] I go to the movies in my head’.)19

When is consciousness?

The different ways in which the body’s neurochemical activity may eventuate in conscious awareness are under intensive investigation, but the question I want to focus on now is a more general one: when does any of this dark and silent internal activity, whatever its eventual form, become associated with consciousness? It is widely agreed in neuroscience that conscious awareness – whatever it is and whatever it is for – emerges alongside complex neurochemical states of biological organisms like us.20 No one yet knows exactly what characterises those particular states, nor exactly which bits of the body-brain are crucial for consciousness. We can be sure, however, that they are complicated, integrated and distributed. There are strong suspicions that they involve regions of the brain like the anterior insula, the anterior cingulate, and areas of the prefrontal cortex, where all the various neurochemical loops come together and talk to each other; but other, more widely distributed, circuitry is almost certainly involved as well.

However, fools rush in, so I shall take a chance and say that, to give a rough approximation, consciousness seems to emerge when some combination of five conditions are present. The first is intensity. Consciousness accompanies external events that are sufficiently abrupt or intense: for example, the sudden ringing of an alarm bell, the flashing of a bright light or a piercing pain. The second is persistence. Intensity seems to interact with the persistence of a stimulus: less intense stimuli often become conscious if they persist for more than around half a second. Softer events can build up to the requisite level of activity for consciousness if they are maintained.21 (At longer levels of persistence, consciousness may fade again through habituation, of course.)

The third condition is reverberation. Persistence may occur not because of the physical continuation of an external event but because of conditions within the brain that allow activation to reverberate, for example round a well-worn neural circuit where resistance is low and activation can, so to speak, keep rekindling itself. It is argued, for example, that we can easily retain a sensible sentence in mind because its elements ‘fit together’ and create such a reverberating circuit, while a list of random numbers needs to be continually rehearsed or refreshed if its elements are not to ‘fade away’ and become inaccessible.22

The fourth condition for consciousness is significance. Consciousness seems to be attracted by experiences that are of personal significance. These may be threats to physical well-being or survival, or to possessions or personal attributes with which one identifies. Even events weak in physical intensity gain access to consciousness under these conditions: a creaking floorboard in a sleeping household; a disapproving expression on one face in an otherwise positive audience. Researchers such as Antonio Damasio, and Gerald Edelman and Giulio Tononi, have suggested that self-related events attract consciousness because they connect with a constantly active representation of the ‘core self’ in the brain, and thus become part of a massively reverberatory circuit. This isn’t a fixed, structural circuit; it functionally connects whatever aspects of internal neurochemical activity happen to be locked into the ‘core self’ at that moment. Thus the ingredients of this core self-circuitry are constantly changing as, for example, some concerns are dealt with and drop out and new ones arise.23

And the fifth and final condition that is likely to bring about consciousness is checking. Activity often generates conscious experience when it is being internally checked or inhibited. As we have seen, the prefrontal cortex exerts all kinds of inhibitory controls over what is going on elsewhere in the body-brain. This is, in terms of the internal neurochemical economy, intensely energy-consuming – and it also creates dammed ‘pools’ of blocked activation that can build up to higher levels of intensity. So there is a strong (but not invariable) association between these inhibitory stockades and corrals, and the emergence of linked conscious experience.24 This occurs, for example, when we are holding back candidate courses of action, such as a contribution to a conversation so that the cost of a (social) error can be assessed; or when ‘struggling with temptation’.

Acts of disciplined thinking tend to become conscious because they require a narrow defile of activation to be maintained against competing possibilities and distractions. (That’s why ‘working memory’ is strongly associated with consciousness: not because ‘that is a place where the light of consciousness shines brightly’, but because the inhibitory effort required to keep tight control of internal events creates the kind of intense, corralled activation that is associated with the appearance of consciousness.) Obviously, whatever is currently connected to the ‘core self’ is likely to be subjected to more extensive ‘security checks’. (Dispositionally anxious people may be constantly on the lookout for remote threat possibilities, and thus become highly self-conscious and ‘inhibited’.)25

This last point is worth stressing. Conscious rational thought is not a different kind of event from feeling or seeing. It too has its roots in the embryonic concerns of the body-brain; it doesn’t come from different stock. Where it differs is in the intensity of activation it attracts, as it unfurls and emerges, by virtue of the degree of neurochemical constraining that it requires. Reasons and arguments well up from the dark depths of the body-brain just as emotions, intuitions and images do. And we often talk to ourselves when there is an underlying tangle of intentions, affordances and opportunities – when the way forward is unclear or conflicted. Such predicaments tax the body-brain’s inherent problem-solving and conflict-resolving procedures, and a great deal of neurochemical excitation and inhibition gathers around the conflict. Out of this kind of biological situation, where action is slowed down or blocked completely, emerges a swathe of consciousness-attracting activity, some of which takes the form of inner speech – i.e. thoughts.

Overall – if you can stand another metaphor – the body-brain functions rather like a pinball machine. Sometimes an event occurs and, especially if it falls within an area of expertise, the system responds quickly and silently. Other times, when the resolution of Needs, Deeds and See’ds is less well honed, or where the costs of error are estimated to be great, there is much more protracted rattling around between different possibilities, and the brain’s electronic bumpers keep the ball ricocheting around, accompanied by the flashing lights and sounds of consciousness. At such times the son et lumière reflects the complicated activity but it does not control it.

Where does this leave introspection – the idea that the mind is a clock in a glass case: a mechanism that the owner can inspect (should she have a mind to)? Where the earlier metaphors for consciousness invited, indeed required, the idea of this ethereal agent (the CEO at her well-lit desk; the wielder of the spotlight), the images of unfurling and welling up do not. The sense of the inner author, instigator or observer is just another frond of the unfurling fern. Both ‘I’ and ‘thought’ emerge, in the moment, as aspects of the same upwelling experience.26 Whatever ideas or experiences come into consciousness, they are, as Shanon says, products of this intricate unfurling, not a direct inspection of it. We never see our own process. Never. The workings of the body-brain are entirely dark and eternally silent. But sometimes out of the gates of the forbidden factory rumble trucks carrying audible and visible goods. The sense of being able to inspect ourselves is ‘real’: as real as anything else that wells up and takes transiently conscious form. But the idea that this sense refers to a real ability to lift up the hood and look inside ourselves – that’s just another idea, and not an accurate one. It’s a unicorn.27

The idea that consciousness is ‘for’ some separate inner ‘I’ to look at runs deep in our culture – and certainly in psychology. To quote just one example, from a recent paper: ‘Even though intuitive processes themselves remain unconscious, they produce outcomes such as intuitions or gut feelings that we can consciously attend to … and use in our judgements.’28 Familiar enough, and seemingly innocuous – yet who or what is this ‘we’ that is attending, being informed and making judgements? Both everyday and academic talk constantly smuggle in the idea of the ghostly agent – the mind – that is clearly other than the workings of the body-brain itself. The idea that thinking, and the feeling that there is an inner someone who is ‘doing’ the thinking, co-arise when the body-brain finds itself in certain kinds of state is hard to keep hold of, especially once we start talking!

*****

This view of the self also fits with a wealth of research that shows, as the University of Virginia’s Timothy Wilson puts it, that we are ‘strangers to ourselves’.29 We know ourselves, it turns out, only through two routes. The first is by observing our own behaviour, and making inferences about what the internal causes or reasons must, or might, have been. Occasionally we admit to this inferential process – ‘I don’t know what came over me. I must be more stressed than I’d realised’ – but mostly we do not. The research shows that we confabulate reasons for our behaviour all the time, and then treat them as if they were direct readouts from the interior – but they are often wrong. Show people an array of identical women’s tights and ask them which they prefer. (Control for other variables like the lighting and where exactly people are standing.) You’ll find that the majority of them will pick out the pair on the right. Ask them why they chose that pair and they will give you all kinds of reasons. What nobody ever says is ‘I chose the pair on the right because that is what I tend to do.’

It turns out that this inferred self-knowledge isn’t very good. Other people who know you reasonably well will predict your behaviour better than you will. Your own estimate of how generously you will give to charity, for example, is, well, generous. If you want to know yourself better, ask a friend. And that’s the second source of self-knowledge: believing what other people say we are like. In adulthood, if we have reasonably good and intelligent friends, what they say about us is likely to be pretty accurate. But it was not always thus. In childhood, other people can be very keen to tell us who we are, and how we ought to be. They may lock us into a cage of attributions based on our gender, our skin colour, or even just on their need for us to be predictable and untroublesome. But those attributions espalier our inner workings, potentially misdirecting our actions and distorting our consciousness.