|  |

Only a gem made from the blood of the first amüli king can save Frendyl Krune’s family from losing everything they’ve worked for—including ending the reign of a pretender to the throne.

~~~

~~~

Please enjoy the Special 3-Chapter Sneak Preview we offer below, or....

~~~

GRAB THE FULL EBOOK TODAY!

FIND LINKS TO YOUR FAVORITE RETAILER HERE:

FRENDYL KRUNE Series at Evolved Publishing

~~~

Please keep reading for....

Too many guards stood outside the manor, their backs straight, expressions stoic, yet a twitch of one’s brown wings betrayed his unease. Something had happened—something worrisome enough that Mother had sent these soldiers to guard my youngest brother, Bondre, and my cousin Delryn while they played in the fountains outside of our estate.

I stood a bit taller, the muscles on my back tightening, my wings ready to snap open at a second’s notice. Even though Bondre acted like everything was fine, the hair on my arms and the down on my wings prickled. I exchanged an uneasy glance with my cousin, Mizendrel, who nodded and rushed ahead, his green and copper robes swirling around his mallard drake wings.

We passed under one of the wide gates that led inside. Even though we usually left the main gate open, especially with children playing outside, tonight it seemed almost a gaping maw, ready to devour us. There was something spooky about how dark it was inside, how not even the light of the two moons penetrated the hallway beyond.

Mizen glanced right then left, his lilac eyes ghostly in the moonlight, before pointing at a toppled table. We headed down that branch of the hallway. Down the right passage, fires guttered in bronze braziers, but to the left, many of the flames had gone out, and only the shadows cast from the low-slung moons offered any light.

The wide passageway, which allowed for three winged amüli larger than us to stroll side by side in fair comfort, seemed narrow and uninviting as we hurried down it. Our shoes slapping the rug-covered stone echoed off of the walls—whapwhapwhap—and ahead, I spotted signs of disturbance.

A chair had been knocked over, and further along, one of our servants righted a torn tapestry while another rekindled the braziers. We burst from the shadows into orange, flickering light, yet even then, the servants paid us no mind. Mizen strode in front of me, and I matched his steps with ease, despite my short height.

Someone had broken in.

Many of our servants had interesting mixtures of less-pure blood; holly tainted with grass and lemons, or some other familiar blood-scents. Ones I had known my whole life. But there was something else behind those familiar scents, something so light and mild that I almost missed it.

I sniffed again. “Mizen, do you smell that?”

He stopped and took in a deep breath, his pale purple gaze whipping across the hallway. “Yeah. What is that?”

I closed my eyes and took another whiff, something creamy, smooth, but strangely mild with a hint of sweet spice hitting me. The unique flavor took me a moment to pin down. “Saffron,” I said at last. “And... is that ambrosia?” No, too rich to be ambrosia. The sweetness meant only one thing, and Mizen caught it before I could.

“Honeysuckle?”

Both of us frowned at each other. Honeysuckle was a common blood-scent from the east, one I’d smelled before, but spiced with saffron, it was so mild and soft to the senses that if I hadn’t known something was wrong, I might never have noticed it.

“It’s stronger over here,” Mizen said, and he pointed down the hall.

I sped up and matched his quick pace. Just as he’d said, the smell grew stronger and stronger. I dared not speak for fear of distracting Mizen. He made a quick left, but I paused and sniffed the air. The scent was stronger to the right, not the left, but when I turned to call out to him, only an empty hallway met me.

“Mizen?”

No response came.

I turned down the right-hand passage, following the tender smell of saffron and honeysuckle into the cramped, dark hallway. Back here fresh air was almost nonexistent, which was probably why Mizen had mistakenly gone left. My stomach cramped, and when the down on my wings stood to attention, I considered backtracking after him. Surely he’d find me once he realized he’d made a wrong turn.

As I inched deeper into the servants’ quarters, the honeysuckle and saffron faded a bit, and twice I had to backtrack and take different turns before I found the scent again. Whoever had come this way was cleverer than I first anticipated. He knew how to hide his blood-scent, which meant he was dangerous.

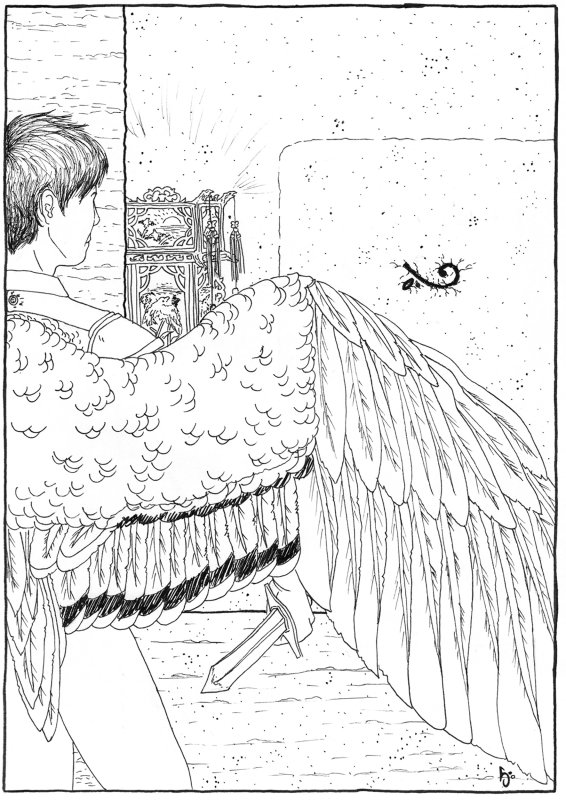

As I ventured deeper and deeper into the mountain, every sound made me want to jump and turn running, so I pulled a dagger from my belt. The small steel blade helped ease my fear but not enough, and I stopped in the middle of the hall, staring toward the next passage. If I turned back, there was a good chance the blood-scent would be lost, and not even our family’s personal guard could track it. Who knew how soon I could find another amüli to come down here with me?

My fingers tightened around the knife’s hard leather hilt, and I wiped my other hand over my face. My hands shook, as did my breath. This trespasser could be dangerous enough to hurt me, and badly.

“Stop it,” I whispered. No one else would do this for me. I had to at least find out which way the intruder was headed, watch from somewhere hidden, and then return to find help. After another, deep, trembling breath, I started forward again, as quietly as I could.

At the end of the last turn stood a door made of solid rock. Scrawled across the door in swirling Beokasvo script was a single character: tyl. The Catacombs. Beyond this door resided the pitch-black maze where convicted criminals served their sentences. I’d never been inside, but Mizen had. As the future lord of our House, he had to know the ‘Combs inside and out.

Why anyone would go in there without knowing the way out was beyond me. The criminals inside remained lost in the turns and passages, even after dozens of decades within the blackness. The walls of the ‘Combs shifted every few minutes, often cutting amüli off and preventing them from finding their way out. I’d heard of amüli who had starved because they were stuck inside of a single, small room of rock.

Starving wasn’t lethal to amüli, and neither was thirst. They were discomforts, and like drowning, would eventually do permanent damage, but an amüli couldn’t die unless their Soulbound did. Even then, I knew amüli—like my mother and father—who had lived for several hundreds of years, because when one Soulbound died, the amüli moved their soul to another human in the same Soulbound Family.

We also healed rapidly, which meant that if the intruder was injured, he likely wouldn’t be for long. I rested a hand against the cold stone door, the normal thump of the hollow space inside my chest speeding up—whump-whump-whump. There were hundreds of amüli inside, and each one of them made a kind of noise, like an echo cutting short when the beating of the empty soul casing in my chest—my Center—struck them. Amüli soul casings might be empty, but they still guided our emotional energy throughout our bodies, which was why they beat like a heart. Each pulse signified the energy pushing through my limbs.

The door itself was a bit intimidating, if plain. No handles, no locks—just the slab of rock that acted as a barrier between me and the screams beyond. Only magic could open it, so this was where my trek ended.

The ‘Combs weren’t a horizontal maze, either. Sure, passageways moved horizontally, but they also grew downward and upward. Mizen had talked about the floor opening up between him and my father during one visit, and he’d almost fallen in. Somehow, though, Father knew the ‘Combs well enough to get them out—almost like he grew up in them.

A chill hung in the air around the door, and when I exhaled, my breath came in steam. While I could still smell the intruder’s blood-scent, there was something... off about everything. I realized then that this was not where the scent led, but where it originated, though that didn’t prove much of anything. No scrapes in the ground from the door moving, no signs the intruder had come through here, but the chill around the door suggested something worse than someone coming through this way.

My fingers and legs tingled in a wash of pins and needles. Someone had cast a spell from this spot. Magic held the blood-scent of the one who cast it, which was why the odor led me this way and why it smelled stronger here.

I shuddered to think what this meant. If one convict could make it out of the ‘Combs and into our manor long enough to weave a spell, so could more.

I followed the blood-scent back toward the main chambers of the estate, though by now, it had mostly faded into all the other usual smells. The farther from the door, the less I smelled honeysuckle and the more I caught notes of lavender. Moonlight appeared ahead, and I exhaled a heavy breath.

Mizen was just down the hall, standing at the doorway of my father’s study. His brow was drawn and his lips tight, arms folded over his chest and his mallard drake wings twitching at the slightest sound.

“Where were you?” he said, brushing his mousy hair from his face when I reached him. Though he tried to keep his voice low, a snap of anger steamed behind the words.

“Sorry,” I said. “I tried to call for you, but you vanished.”

“I thought you were right behind me. The blood-scent disappeared, so I turned back.”

“It didn’t disappear, though,” I said. “It led to the door of the ‘Combs.”

Mizen’s pale purple eyes widened, and his nostrils flared, but he said nothing else. Instead he nodded toward my father’s private study.

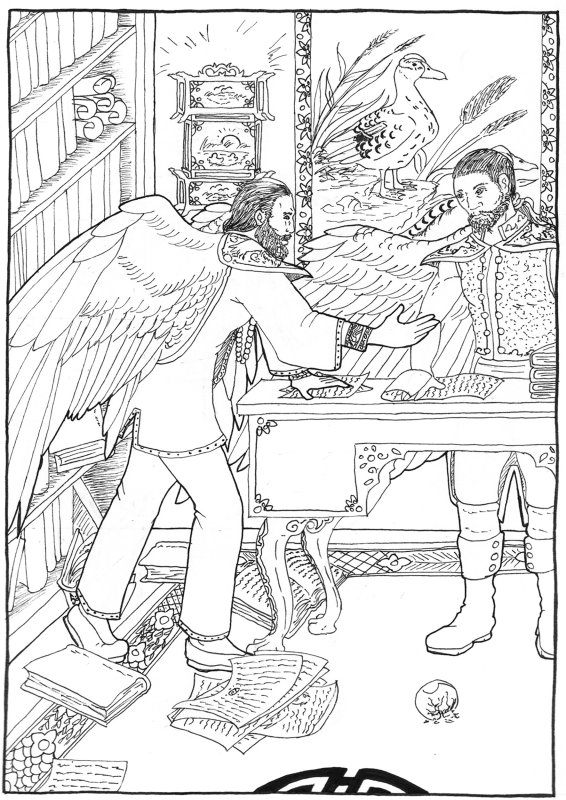

Within, half a dozen amüli cleaned the remains of my father’s items from our Soulbound Family in China. Mother slid books back onto shelves in slow, methodic movements, and Father stood behind his desk, glowering as he thumbed through ledgers and documents.

Tonight, my father was garbed in fine trousers of soft brown leather and a vest of emerald green. The vest had two tails in the back, and two shining rows of copper buttons ran down the front, with embroidered ducks around them and along the hem. His wings—mallard drake wings, like Mizen’s—fit neatly through a hole on the back of the vest. A green ribbon gathered his long, black hair at the nape of his neck, and unlike many of my uncles, Father’s beard was neat and trimmed with only a few scant gems and beads.

My uncle Jyntre, captain of the Krune Guard, was there as well, along with two soldiers. Cut emeralds glittered in the black curls of his beard, and a few beads of brown stone and wood almost vanished against the dark hair. Unlike Father’s Western garb, Jyntre wore a green shirt and vest of a master warrior along with traditional Chinese trousers.

Our House flag bore a pair of green mallards on a brown banner, so the guards wore brown trousers and green tunics more closely resembling my father’s attire than Jyntre’s.

Broken glass shimmered across the floor beyond the enormous doorway. Chairs, small tables, and books—dozens and dozens of them—had been toppled to the ground. Some drawers from Father’s desk stood askew, and one was even beside the doorway.

I leaned over and began stuffing the contents back inside. Mizen took my cue and gathered up a bunch of the fallen books.

“What happened?” I asked, straining to keep my voice neutral.

Father turned toward us, his lavender eyes scanning my face, as if he didn’t quite recognize me. “What is he doing here?” he said to Mother. “Boy, aren’t you supposed to leave for Lendre tonight?”

“No, sir,” I replied. “Not until the morning.” Tomorrow at dawn, I was meant to leave the city and train as a page beneath one of my father’s liege lords. With everything happening tonight, part of me doubted the trip would happen.

My mother, a stately woman, silently slid an unbound book back into place before she turned her tired eyes on me. She exhaled, her shoulders sloping forward. Her wings—white, speckled in brown and red—almost drooped to the floor. Like most women in Drüssyevoi, she wore tight leather leggings hidden beneath long, loose robes of silk. The colors of her outfit matched Father’s, though she wore brown embroidered in green, the embellishments far more subtle.

My parents’ clothing reflected the spirit of our Soulbound Family, and we often wore silks and other fine cloth gifted to us. The Lis, once a prominent family in China, had hosted our souls for hundreds of years. They had fallen from power at the end of the Tang Dynasty in AD 907.

“Frendyl,” Mother said, “you should be packing for your trip.”

“What happened?” I demanded.

Her voice had sounded so sweet and reassuring, but now her jaw tightened, and fear glinted behind her brown eyes. Because she was a Krune by marriage not blood, she didn’t carry the burden of my family’s pale, weak eyes. This curse our family suffered resulted from a jealous king who resented an ancestor of mine for gazing at the queen too long during court. It all sounded a bit ridiculous to me. According to the stories, it took many generations for us to regain our full sight, though our eyes still remained sensitive to light at times. Time and new blood had done our House good.

“You are not to ask such things,” she said, that melodious lilt replaced by something tight and nervous. “Go and pack. You leave tomorrow at dawn.”

“I don’t—”

“Just go.” She waved a thin arm in my direction, her long, narrow face contorted in uncertainty, her eyes darting between my father and I. “Go prepare for your trip.”

Mizen stepped forward. “Frendyl discovered something.”

Father frowned but nodded for me to speak.

“Mizendrel and I followed the intruder’s blood-scent into the mountain,” I said.

Those words grabbed my father’s full attention, and he whipped his head toward my cousin. “You did not mention this.”

Mizen shrugged before explaining, “I struck a dead end. The scent vanished.”

“And you, Frendyl? Did the scent vanish for you?”

Pride welled in my chest at Father calling me by name. “No, sir. It faded a bit, but I followed it to the door of the Catacombs. I... I think the intruder went inside.”

Uncle Jyntre waved a dismissive hand. “Then he will be lost forever. A thief who takes himself to our prison. How convenient.”

I shook my head, but my uncle longer paid me attention, and neither did Mother.

Father, on the other hand, stared at me with curious intensity, never once blinking. “Is there more?”

“Yes, sir. I... I think he came from the Catacombs.”

His eyebrows arched and his lips parted in surprise. “That’s quite a claim, lad.”

Jyntre snorted. “No amüli knows the way out of the ‘Combs. Don’t listen to the child.”

But my father raised a hand, cutting him off. “Explain to me what you think happened.”

“I...,” I paused, unsure how to explain it. “I think this person figured out how to leave the ‘Combs. I’m not sure how, but it must have taken a long time to learn the patterns of the rock.”

“The rock doesn’t move in patterns,” Jyntre snapped. “To enter and exit, you have to....” He raised his hands and shook his head. “I apologize, Ilbondre.”

Father ignored him and narrowed his eyes at me. “How do you know this?”

I considered just shrugging but felt that would be too passive. No, if I wanted his respect, I needed to explain my accomplishment. “I followed his blood-scent, but I didn’t go inside the ‘Combs.” I paused, not knowing how he would react to that. Perhaps I should have followed the intruder in.

“Did you see him?”

“No.” I shook my head, my shoulders and wings sagging. “He was gone by the time we found his scent.”

Father rubbed his beard. “Describe it to me.”

“Honeysuckle,” I said. “And saffron.”

He turned to my uncle. “Well, Jyntre, I think we’d better have a look and see if the lads are right or not.”

Uncle Jyntre snorted and waved a hand at the servants to continue clearing the mess. “If it must be so.” He paused then pointed at me. “You, come with us. Mizendrel, see that children are safe.”

Mizen pulled me aside before leaving the room. “When you’re in there, trust yourself to know where to go. That’s how you get out.”

My brows knitted in confusion, but before I could ask him to clarify, Mizen whirled away and hurried toward where we’d left the children outside.

Uncle Jyntre and Father guided me down to the door of the ‘Combs. The entire way, I gripped my dagger, the hairs on my arms prickling to attention and the down on my wings tingling. The intruder must have been long gone by now, but the deeper into the mountain we ventured, the more nervous I grew.

At last, we reached the single word scrawled into the wall of rock. I stopped as far back as I dared, waiting for Father or Jyntre to say something—anything.

“I smell it,” Father said after a moment. He turned to me, his lips curled in an approving smile. “Well done.”

“A trail of magic,” muttered Jyntre. “Frendyl, lad—I owe you an apology. You were right about someone being here.” He frowned. “Ilbondre, what do you suppose this means?”

The smile vanished from Father’s lips, and he rubbed his bearded chin, his brow tightening as he frowned at the door. “Nothing was taken from my study. At least nothing we’ve noticed yet.”

Jyntre shook his head.

I narrowed my eyes at the door while considering what had happened. Someone had come in through the Catacombs and cast a spell, but it seemed the magic had done nothing but make a mess of Father’s study and the passages it had followed. Why would someone break into our home just to make a mess?

“It was a distraction,” I said.

Jyntre glanced at me, and Father nodded for me to continue.

I lifted my chin. “Whoever broke in wanted to break someone out of the ‘Combs before we could catch on. The spell—could it have been a distraction? A way to keep us from realizing what happened?”

Jyntre laughed, as though I were a fool. “Breaking out of the Catacombs is impossible.”

Father rested his palm against the cold stone and murmured a few words. While I couldn’t tell what spell he cast, the sudden thickness of the air, like a static charge, told me he pulled magic from the earth. I knew the very basics of magic—that we drew power from one of the three gods for different reasons—but anything else was beyond me.

The wall slid open, rock grinding loudly against stone as the entire end of the passage moved aside. Blackness spread beyond the door. Not the sort of darkness you get from wandering a hall at night, but more complete. The utter lack of light made my heart constrict. I glanced over at Father, but his expression remained unchanged. Of course, he’d seen this before, but I still thought that something would show.

This sort of darkness even the guttering braziers couldn’t touch. It was like all light ceased to be at the threshold to the ‘Combs. Where the light stopped, screams and moans began. They sounded muffled, and I supposed that was because of a barrier of magic placed around the borders of the Catacombs.

“Come,” Father said.

My Center thumped wildly along with my heart as I stepped over the border after them.

The barrier was cold and almost sucked my breath away. After a single step, I could breathe again, though I didn’t inhale salty sea air. Something else met my nostrils, something foul, like garbage and day-old fish baking in the hot sun. I gagged and coughed, shaking my head and swallowing down the urge to throw up, though the sour taste of bile entered my mouth before I could force it back.

My feet stumbled forward beneath me—at least, I hoped I was moving forward. I tried to follow the sound of my father’s steps, or my uncle’s, but a shriek sounded nearby, and I floundered away from the opening. A heavy, desperate moan bubbled up somewhere to my right. I froze, unwilling to walk any deeper into the dungeon.

Jyntre grabbed my wrist and tugged me after him. “Trust me, boy, and trust yourself to get through this place.”

Despite his words, once he released my wrist and the door to the ‘Combs ground shut, I found myself inching along, clutching my dagger to my chest. A dwindling cry for help echoed, followed by the crunch of bones breaking as someone landed at the bottom of a pit. I cringed and bit my tongue then shuffled my feet a little slower, just to ensure I didn’t accidentally follow that nasty fate.

Once the convict had landed, his screams didn’t stop. This time, though, instead of wailing for help, he shrieked in agony, high, long, and loud, followed by sobbing. Someone else, a woman, shouted for the injured amüli to be silent, while others banged and scratched on the walls of the shifting cavern.

Were we in another place, away from the world I’d always known? I lifted my hand but felt disconnected from it, as if my body weren’t moving, and I was just imagining that it was. I shuddered and dropped my hand back to my side, though I kept the dagger close as I followed Jyntre and Father.

The darkness bothered me even more than the screams and the begging of the trapped amüli did. Something about the nothingness that met my eyes and the constant howls that came to my ears disjointed my perception of the world around me. I began to wonder if this was what it would be like to lose my soul.

It seemed we walked for hours, until my calves ached and my feet throbbed. The soles of my shoes were hard boiled leather, not meant for long treks, and the creaky, angry material kept digging into my ankles. Not to mention my pants and vest, which were both sweaty and heavy. I wiped my arm across my forehead, surprised at how cold my skin felt.

This place must have had some sort of enchantment on it. No matter how far we traveled, I could never quite hear what the hundreds of voices were calling out—just general screams for help and other noises. At one point I reached out to either side of me to see if I could touch the walls. Nothing but freezing, damp air greeted my fingertips. Even when I spread my wings as wide as possible, they met with nothing, and I remembered that the floor might gape open before me at any moment and drop me into nothingness.

I considered asking for a break when light appeared ahead of us. I blinked and grimaced as we grew closer. We’d made it... well, somewhere. The darkness had been so complete that my eyes ached, and I rubbed them with the heel of my hands to help my vision adjust.

We stood at the mouth of an exit, which faced the ocean and was tucked into the cliffside. Waves crashed in the near darkness of night, and the two moons hung heavy in the sky like sleepy eyes. There were two pairs of footprints trailing away in the sand, but those could have been made by an animal not an amüli.

I frowned. “The ‘Combs don’t have an exit, do they?”

“None other than the door we came through,” my uncle said, nervously pulling on his beard.

“So this?” I asked, gesturing at the massive hole we had emerged from.

Father spared me a glance. “Someone has learned how to bypass the enchantment on the Catacombs. They know the secret.”

I shook my head and stared at the black hole. “That’s not good.”

“It’s worse than not good. It means someone knows,” Father said.

“Knows what?” I asked.

The silence between them told me enough. Someone, somewhere, had just broken out of the most notorious prison in the Amüli Kingdom. I frowned and turned my gaze out to sea, then lifted it to the sky. Stars dotted the heavens, and silvery clouds drifted lazily overhead.

“We need to seal this off,” said Jyntre.

Father gave a curt nod. “Frendyl, you are to return home and pack.”

“Who did they set free?” I asked.

“I cannot be sure just yet.” Father was right; the wind had carried away both blood-scents, meaning we had no way to track whoever had escaped. “Return home and prepare for your trip. Jyntre, I need you to bring your best casters to me.”

My uncle tugged on a gem in his knotted beard. “If the amüli who broke into the ‘Combs is as powerful a caster as I suspect, my men won’t find much.”

“I’d rather try than not.” Father then waved me away.

Jyntre cast me a last glance before I ran a few steps and launched into the sky, once again sent home to be safe, once again expected to always do as I was told, even when I didn’t agree. In xiangqi—Chinese chess—there were many pieces, but I always saw myself as the Advisor, a piece that could never leave the area of the board called the palace. Never able to leave Drüssyevoi of my own volition, never able to be my true self, I was always tied down to being the person Mother and Father wanted me to be—a quiet child who always did as told. Well, no longer. I’d break out of my own palace one way or the other.

To do that, I needed to know what was really going on, and Father seemed to be withholding something important—so important that he would only reveal it to Jyntre. As quietly as possible, I glided up and away before curling back around and landing on a ledge out of their sight, but just within earshot.

“How are you going to find the person who did this?” I heard my uncle say.

“Someone capable of breaking out of the Catacombs must be powerful enough to avoid normal means of detection,” Father said. “Which means the Blood of the Sun may be the only way to track the one responsible.”

Whoever had done the impossible could hide from normal magic, but if the stories were true, no amüli was strong enough to hide from something as powerful as the fabled gemstone containing the blood of the first amüli king. The gem’s properties were legendary. I’d grown up hearing tales of the stone’s wielder crushing whole armies in a single blow and wielding magic as though he were a god.

“Do you have any idea where it might be?” asked Jyntre.

“No, but Melroc believes he is close to uncovering its hiding place.”

I leaned against the cold stone of the cliff side and frowned. My uncle Melroc was their youngest brother, a relative I hadn’t seen in years. He was famous for traveling the world and gathering information on new lands and the people who lived there.

“Then we should send word to him,” Jyntre suggested.

My father said, “He is already on the way. His ship arrives on the morrow to collect supplies for his voyage. I’ll send Mizendrel to speak with him on my behalf.”

The Blood of the Sun, an ancient artifact that hadn’t been seen in so long few doubted it was real, stood between my father and whoever had escaped our prison. I crouched then launched back into the air. No way was I going to Lendre now. Not while so much rode on Uncle Melroc finding something as important and powerful as the Blood of the Sun.

Father had treated me with such respect tonight that I felt it was my duty as a knight-to-be to aid Uncle Melroc in his quest for the stone. A knight needed to be able to put aside his own selfish desires to help others, and while I yearned to train under Lord Veren’s son as a page and prepare for my life as a squire, this was far more important. To prove myself worthy of being a knight—and not just any knight, but one of the best—I’d need to leave with Uncle Melroc in the morning.

I closed my eyes and hoped Father would still respect me when I returned.

The vessel Melroc captained had yet to arrive, though clouds rolled in over the ocean, and the waves grew larger and larger with each minute. Mizen and I strolled toward the lapping tide as groups of amüli gathered on the beach with barrels of fresh water and crates of food.

“You were supposed to go train with Lord Veren’s son,” Mizen said, “not to go on this... this senseless voyage.”

My stomach knotted, both in guilt and uncertainty. Not many amüli my age could attempt leaving home and get away with it. Of course, I had to hope Mizen wouldn’t say anything and Uncle Melroc would believe the letter I carried in my pocket with my passport.

“It’s not senseless,” I replied. “Besides, you’d do the same thing.”

“Not even close.” Mizen crossed his arms over his chest, flexing his drake wings until they fanned wide to catch the earliest rays of sunlight. “I’d do as I was told.”

“More is at stake than just my father’s reputation,” I said. “What if they can’t find who broke into the ‘Combs? What if the intruder comes back and breaks someone else out?”

“You don’t even know if anyone got out.”

“There were footprints in the sand—two sets.”

“No, there were divots in the sand that might have been footprints.”

I shook my head. “Do you think people will accept that? Because I don’t. If our fathers can’t track the person who did this and the people find out, it could lead to chaos.”

Mizen exhaled. “Fine. I still don’t like it, though.”

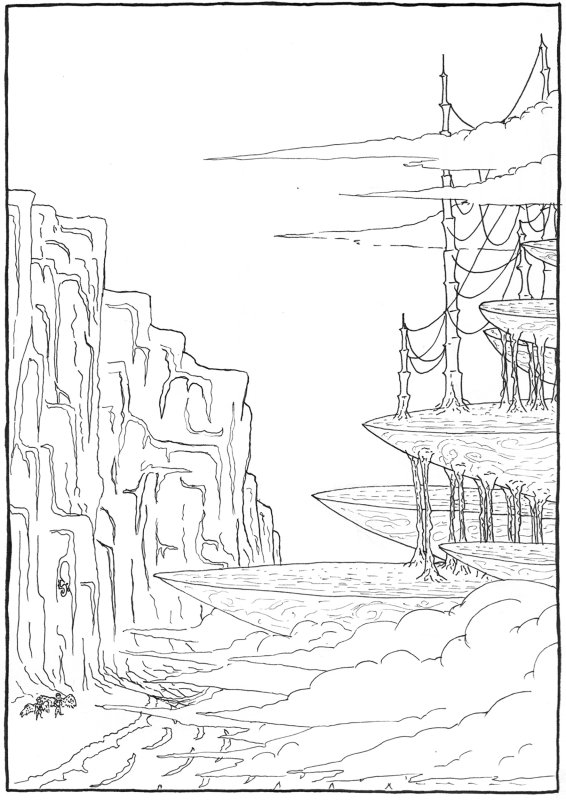

“Look.” I pointed toward the sky, where the first rays of dawn touched the clouds above. The light shimmered and glowed unlike any I’d ever seen before. Then, upon closer inspection, I noticed a ship emerging from the heavens, its massive decks similar to thick sand dollars piled on top of one another, the flat side facing up. Pillars of smoky clouds held roofs in place, and when I squinted, I spotted individual chambers with wispy openings that looked a lot like carved scrollwork windows.

“Astounding!”

“You said it.” My hands clenched, and my stomach curled in on itself. In that moment, I was glad for the decision to skip breakfast—it might have come up when I realized this massive cloud-city was what I’d be using to traverse the ocean. Would I have to fly the entire time? That seemed foolish. Certainly, something—rocks, wood, or another solid substance of some kind—would give me a place to roost at night or when my wings grew tired.

As Mizen and I gawked, the vessel dropped from the sky toward the soaked sand, where it finally came to rest. The amüli around us hauled their crates and barrels over their shoulders and made their way toward the lowest of the sky-ship’s giant disks.

“Want me to escort you?” Mizen asked, probably due to curiosity more than wanting to act as an escort.

I shrugged. “Sure. Let’s go.”

Mizen took the lead. Since our Uncle Melroc captained this massive vessel, Mizen would be the better one to suggest I join the trip. His drake wings got him places I could never dream of reaching. Only one drake per generation was born to House Krune, and Mizen would eventually take my father’s place as the lord of Drüssyevoi and become one of the most powerful men in the kingdom. Every other Krune had the wings of hen mallards, and we were destined for... well, it was hard to say. Some of us became knights. Others, like Uncle Melroc, joined the Order of Kravaldîn and set forth to explore the world.

As we hopped up to the first deck, I managed a closer peek at what the vessel was made out of. Clouds were my first guess, and the swirling structure confirmed my suspicions. Instead of us sinking down into softness as I’d expected, the cloud disk we walked across was as hard as stone. I paused to tap the toe of my shoe against it.

How the sky-ship was made and how it floated on nothing but air was beyond me. How were the decks solid enough to walk on while looking fluid underfoot? What about the weight of it? Did it always fly like it had before touching down? I shook my head and hurried after my cousin.

As we strolled by a large group of amüli, the hair on my arms and the back of my neck prickled. The down on my wings stood straight. My chest constricted, and for a few seconds, the air felt so heavy I feared I’d never breathe again.

And I knew why.

Even Mizen stopped walking, and we both watched the group of men work. These amüli were casters, quickly pulling the power of the gods from the ground below and working the energy into new forms with artful commands. The majority of the forms became fat arches of swirling color, which glowed and cast fractured light across the deck. Blue and teal made up most of the arches, but every few moments, a swirl of red would intermix with it, though the energy never became purple. One of the casters guided the blue energy up to a higher deck, and others above caught it before forcing it into the clouds, like a waterfall running backward. While some of the casters stocked away the water and food, the majority of them forced fresh magic into the sky-ship.

A crack of light followed by a dampened boom shook the ship beneath my feet. Within the confines of the clouds, a storm brewed. Despite the bright colors, this wasn’t a display of casting finesse. This was magic in its raw form, and it spun with a hundred new shades of blue and red.

Without magic to fuel such a massive spell, the entire ship would collapse and we’d all end up in the ocean. I was glad for the gods’ aid, since swimming wasn’t something I was good at. Wings made it difficult to move through deep water.

The ocean was no place for an amüli, but my aunt Nymdre used to pace the beach every morning and evening. When I was younger, she had an accident while on one of her walks and was lost at sea. But she didn’t actually die. Thanks to her Soulbound human keeping her soul safe, she stayed alive but drowned over and over again. I recalled her sunken cheeks and the lines of black veins that webbed her pale skin when Father pulled her from the waves. After she came to, all she did was scream over and over again, until Father forced her into a Soulless silence to end her suffering.

It was not a pleasant memory.

Soulless amüli lost their souls, and in a sense, their lives. They survived in a state of nonbeing, and though their bodies never truly decayed, their veins would congeal, their eyes would become blind, and their wings molted. Some scholars claimed Soulless amüli were still somehow alive, though I doubted it.

I pushed the thought away and urged Mizen to keep going. The sooner I met with Uncle Melroc, the better. I had vague memories of him from childhood, but I hadn’t seen him since my fifth birthday. Father and King Urudel always seemed to find a use for him, and that use rarely kept Melroc in the city.

As we walked across the deck, I realized the floor of the ship glowed with every step we took. Most of the time, the clouds pulsed with blue, but occasionally, red would crack across the surface.

I knew about the gods, of course, but not much. Matrisk fueled the red magic, since she was often associated with anger and offensive spells, and was warmer than the other gods—almost searing hot, according to my texts. Batrisk was the bluish-green magic, colder than the wintery wilds to the far north; he was used for defensive spells, and I figured he also fueled whatever spell these casters used. There was a third god, one I understood little about.

I hurried after Mizen through a doorway into another room formed from clouds, and from there, we flew up to another clam-shaped level. Some of the lower levels had stairs between them, for amüli who were injured or too young to fly. After we touched down, Mizen indicated an enormous door, which was wide enough for us both to pass side by side without complaint. The character for captain was emblazoned above it. The word glowed in the clouds, a cool, inviting blue-green.

“Should I go in with you?” he asked.

“I hoped you might. Uncle Melroc hasn’t seen us since we were children.”

A fond smile crossed his lips. “All right.”

He approached and knocked, which surprised me. Part of me had expected the door, also made of the strange clouds, to merely vanish beneath his touch. Instead, it sounded like a solid surface to my ears.

“Enter,” a heavy voice called out from the other side.

The door vanished, and we slipped inside. Within was a wide open chamber, and in the center stood a massive table made from the same clouds as the rest of the vessel.

Uncle Melroc shut a massive tome as we walked in. His periwinkle eyes glinted when he noticed us, and he stood, opening his mammoth arms. Unlike Father and my other uncles, who were tall and thin like Mizen, Melroc was stout and strong, like a moving mountain. He ran fat fingers through his thick, wild beard. Beads of jade and polished wood and some tiger’s eye gems glinted in the light that seeped through the cloudy walls.

I recalled Melroc striding into our feast hall years ago—wide, tall, grinning, his hair less peppered with gray back then, his face painted in bold hues of green and copper. Whenever he turned, his hen wings had almost always hit someone. When Father called him up to stand beside him on a raised dais of rock, Melroc had jumped into the air. The second his wings snapped open, I thought he’d fall, but somehow his girth glided safely to the dais. Though Uncle Melroc was enormous, he wasn’t fat—not even back then. Every ounce of him was muscle.

“Lads, lads, to what do I owe the visit? Come now, a hug.”

Mizen hugged him, though quickly, as if someone might see. He pulled away and motioned to me. “Uncle, you remember Frendyl.”

“Ah, Ilbondre’s youngest.”

I smiled but shook my head. “No longer, sir. I have two younger brothers now.”

“No need to be so formal.”

“Lord Ilbondre has requested you take Frendyl on as an apprentice and that he assist in....” Mizen paused. “In seeking what you’re after,” he finally allowed, though only in a low voice.

“Ah. Let me see, then.” Melroc held out a beefy hand, as if expecting a letter.

Mizen nodded at me, and I pulled the vellum page from my soft leather vest. A spurt of fear raced through me. The letter was forged, of course, Mizen using his far neater handwriting to pen the message within. The green wax seal, which Mizen had stolen from Father, had the two mallards of our House pressed into it. The wax popped when Melroc thumbed the letter open.

His eyes narrowed as he read the message, and his lips drew into a tight frown beneath his beard. For a few terrifying heartbeats, I worried he wouldn’t accept the letter—or me.

Then he motioned to Mizen and said, “Lad, tell the high lord thank you for his generous donation, and I’ll take good care of Frendyl here.” Still, as he spoke, his gaze, which had gone steely, remained locked on me.

I tried to stand tall, as if I were supposed to be there.

Mizen rested a hand on Melroc’s arm. “Thank you, Uncle.”

“Sure, sure.” Melroc pulled him in for a second tight hug. “Now, I haven’t seen you both in far too long. Would you care for some spiced mead? Or some schlava?”

“I appreciate your generous offer,” Mizen said with a laugh, “but I must return to Drüssyevoi.”

“Much to accomplish today, eh?”

“More than I’d like,” my cousin said with a warm smile.

“Well, get used to it, lad. You’ll be ruling the city before you know it, then the work will never end.”

Mizen likely wouldn’t gain control of the city for another couple hundred years. I might even become a knight before he took his spot as high lord of Drüssyevoi. Still, he smiled at Melroc’s comment.

Before he left us, Mizen gave me a fond squeeze on the shoulder. “See you soon,” he mouthed.

And then I was alone with Uncle Melroc in the room, the clouds in the walls swirling lazily and closing the doorway, as if guided by some wind I couldn’t feel.

Melroc sank into his large chair and exhaled before running his hand over his face. “Now, Frendyl, explain to me why you two lied.”

My jaw dropped open. The way he’d handled Mizen, I was sure we’d gotten away with it and that Melroc believed the letter was from my father.

“Look, I know my brother’s handwriting and the scent of his blood well enough to tell the difference between this”—Melroc tossed the letter onto the table—”and the real thing. Now....” He leaned forward, rested his elbows on the edge of the table top, and pressed his lips against his clasped hands. “Explain to me why the two of you would lie.”

I sucked in a deep breath and let it out in shaky bits. Not how I thought this would go. Melroc was my favorite adult relative—and I have a lot of them, so that was saying something—and the disappointment radiating from him made me want to curl into a tiny ball and fall through the floor.

“Sir, I....” Again those words stuck somewhere in my throat. I bit my tongue to ignite them, and everything spilled out. “Someone’s broken into the ‘Combs, and we think the intruder released a prisoner—I’m not sure who. But they used a spell to distract everyone while the breakout happened. Father said using the Blood of the Sun is the only way to find those responsible, and if we don’t find them soon, the people might find out, and it could cost our family everything.”

I’ve never scared easily, but something about the circumstances that had set everything in motion encouraged me to continue. “I was supposed to train as a page under one of Lord Veren’s sons in Lendre, but this seemed much more important.”

When I paused to catch my breath, Uncle Melroc lifted his hand to cut me off. “This is serious, Frendyl. Did your father say whether he has everything under control?”

I shook my head, my face cold and clammy. “No, sir.”

“And I’m going to assume he doesn’t know you came to me instead of leaving for Lendre.”

I gave a single nervous nod.

My uncle leaned back in his chair and held his hand over his face, as though thinking. Each second of silence only made the pounding of my Center louder—WHUMP, WHUMP, WHUMP—and gave me more time to fidget and wonder what would to happen to me. Nothing could be done to Mizen, since he was predestined to be the high lord of Drüssyevoi, but I could be disowned, sent off to another city—or worse, sent to court in the capital. There, if I were convicted, I’d never see my family again.

Sure, my family had its faults, but I still loved them. I was willing to give up my page training to help Father out. Couldn’t my uncle understand that?

“I suppose I don’t have much of a choice,” said Melroc finally, and he leaned forward, though he shook his head slowly. “You need to understand the gravity of what you’ve done, though.”

Now that sent a chill between my wings. I clamped my jaw closed as hard as I could, resolute in my decision not to ask what he thought Father would do to me.

“Come, sit. We should talk.”

I sank into another of the cloud-made chairs, this one across the huge table from him.

“So, you know my crew and I are seeking....” Melroc nodded, staring right at me to let me know that the name wasn’t something we could discuss aloud. “And it sounds to me as if we must be quick about its return. Tell me, did you or Mizendrel say anything to anyone else?”

I took in a deep breath, my uncle’s lavender-and-plum blood-scent helping me relax now that he was closer. A least he hadn’t sent me away in shame—yet. “We... tried to keep quiet about it. Why?”

“The... thing we’re trying to find has garnered a lot of attention, and not all of it from upstanding individuals.”

I frowned. “If it’s so important to get it back so fast, why can’t we use mirrors?” Amüli used enchanted mirrors to get from one place to another, including Earth. The crossover was almost instantaneous, so it made more sense to use those than a ship of clouds, which would take days or weeks to travel from one place to another.

“Imagine we reached Erytel or another city, only to discover there is no mirror where we are headed. How would we get there? With a crew of casters hired in that city?”

I nodded. “Sure. Why not?”

He scowled. “I only trust those on this vessel. It also saves me time with customs.”

That made sense. Travel through mirrors was strictly regulated; a great deal of paperwork was required to leave one city and go to another, and if Melroc needed a large crew—especially for protection or to reach a destination where mirrors might not exist—the delay could be longer than the few days it took to traverse the Madirakovi Strait.

“Now, I can’t have you waltzing around as if you’re a cabin boy of sorts.”

“Why not?” I blurted. “I’m fine with working from the bottom up.”

He shook his head. “That’s not how this works. Your blood reeks of someone from a powerful House. Anyone with half a wit aboard this vessel would know you’re related to me, and there’s no point in trying to hide it. Instead I think you’ll work for me.”

My lips curled into a grin.

“Don’t be too excited, lad. You’ll still have to work, and hard. I can’t favor you in any way other than taking you on as a....”

“A what?”

He scratched his beard. “‘Cabin boy’ ain’t right. ‘Apprentice,’ let’s say, at least until I come up with something more apt. You’ll take minutes at my meetings, strip my bed and make it again, clean my clothes, empty my chamber pot, scrub my quarters, and share the same chores as the other crew your age.”

My expression must have given away my surprise at the mention of others my age on board, because he said, “Aye, one of your second cousins is here, and a few other runts whose fathers wanted them to learn something of the world. You’ll be expected to do as they do, understand?”

“Absolutely,” I said.

“Report to me this evening. My quarters are through that door.” He motioned to his left. “I need new linen tonight, and the chamber pot needs to be scrubbed before sunset. Go and join the crew, now. Ask Lord Loudrum to give you something to do while I think.”

I rose, warmth spreading through my chest and into my face and heavy limbs. Even though the meeting offered a glimpse at how much my uncle disapproved of my choices, I seemed to have won some respect from him.

Melroc stopped me as I turned to leave. “Once we’re well enough at sea, I’m going to contact your father and explain where you are. You can tell him why when we return.” He waved an enormous hand at the door. “Oh, and Frendyl? You’re to call me ‘Captain’ or ‘Captain Melroc’ in front of the others. Understood?”

“Yes, sir... er, Captain.”

He nodded and opened the book he had been reading, signaling that our meeting was over.

I stepped outside of the room and breathed in the brine-laden air with relish. Though the cloudy walls let fresh air inside, I felt as if I’d just emerged from the ‘Combs. The sun had risen above the water, casting a strange blue-green glow over the sky-ship.

A number of amüli nearby shouted to one another, and I heard one cry, “Cast off!”

I grinned and raced toward the edge of the deck, leaning out and catching the casters work in unison to raise the ship by pinwheeling their arms, a low, rumbling chant coming from their direction. Blue magic seeped from the deck beneath them, and when I looked up, I caught sight of another team doing the same thing.

Swirling blue energy gathered beneath the lowest decks and forced the sky-ship into the air with a great heave. I stumbled as the ship rocked, and the final jerk almost knocked me from my feet as the ship rose. The lead casters—masters of individual groups—roared orders before continuing the chant. Their heavy voices boomed above all others and added a deep bass to the tone of the ritual.

Humans might use sails and oars to power their sea vessels, but magic just seemed so much more effective, and the ship finally arched toward the heavens. A rolling storm beneath the lowest deck of the ship boosted the vessel higher, and only when peering closer did I realize the storm was actually comprised of magic that had gone misty.

Once the sky-ship had leveled out, I squatted, opened my wings, and pushed off into the air. Now I just had to find this Lord Loudrum.

It didn’t take me long to narrow him down from the others. Though the vessel was massive, only one amüli gave orders to a group of children. There were three others about my age, and I glided down toward them before landing.

The lord frowned at me. “Well, look who decided to join us. And who might you be?”

“I’m Frendyl,” I said. “Are you Lord Loudrum?”

“Aye, and you’re late. Worse than my son,” replied the lord, staring at me from over his long nose and arching an eyebrow. A yellow, stringy beard covered his chin, and his head had strands of thinning hair to match. Fine breeches of gray wool covered his lean form from boots to stomach, and under tawny spotted sandpiper wings he wore a long fitted brocade coat of brown and gold. Like the others around me, his presence sent loud whumps through my chest and up my arms.

A whiff of his blood-scent offered up a bouquet of something familiar.

Honeysuckle and saffron.

He was the one who broke into our estate. The thought sat ill with me, and my stomach tightened. I clenched and relaxed my hands, my legs shaking as I took a step away from him.

Loudrum raised an eyebrow at me and stepped forward. “Lad?”

That made my mind up. I turned and raced for the edge of the platform as fast as possible before launching into the air and swooping toward my uncle’s quarters. Blood pounded in my ears as I landed on the deck below and stumbled toward the door. I pounded against it with both hands until the heels of my fists ached.

The door swirled away, and I lurched inside, out of breath and panicked, worried Loudrum had followed me down here.

“What in the name of the king is wrong with you?” Melroc demanded.

“Loudrum... honeysuckle! Saffron!”

Melroc lifted his hands. “You’re not making any sense, lad. What are you on about?”

“Loudrum’s the one who broke into the Catacombs!” I shouted. “He has the same blood-scent as the amüli I tracked!”

My uncle pointed at the chair for me to sit. “Stop. Breathe. I need you to make sense.”

I shook my head and stared out the still-open doorway, my hands shaking, my legs numb from the knees down. “Listen to me! The person who broke into the ‘Combs last night had Loudrum’s blood-scent. It has to be him!”

Melroc frowned and closed the door with a wave of his wrist. “This is a rather egregious accusation, Frendyl.”

“I know it sounds insane, but please listen to me.”

“I am.”

“The whole reason I’m on this ship is because I want to help you find the Blood of the Sun so Father can track down the amüli who broke into the ‘Combs,” I blurted.

Melroc’s cheeks drained of color, and he slapped his hand over his face. “Frendyl...,” he said with a growl.

“If he’s the one who broke someone out, we need to find out who it was, and now! We need to know where he went, why he was let out.... We need to—”

My uncle grabbed me by the shoulders and shoved me into a chair. “Stop talking.”

My lips clamped shut.

“Good. Now it’s my turn.”

I opened my mouth to speak, but Melroc held up a hand. “No. This is serious, Frendyl. You can’t go around causing this sort of panic. If Lord Loudrum was the one who broke into the Catacombs, we’ll know soon enough.”

“How? What are you going to do about it?”

“I said to be silent,” he snapped.

At that, I ducked my head and wanted to hide beneath the clouds.

“You cannot run around yelling things like this. No one but myself and a select few know what we’re after, and I intend to keep it this way. You will return to Lord Loudrum and pretend none of this ever happened. Leave it to me to determine whether Lord Loudrum broke into the Catacombs. Understood?”

“But I—”

“This is not a job for a child. Do you understand me? Stay out of it, Frendyl. You did well enough by bringing me your suspicions, but if you whisper a word of this to anyone, I’ll ensure you’re sent back to the capital.”

I lowered my head. “Understood.”

“Good. Now return to Lord Loudrum and apologize for your rudeness.”

I rose on trembling legs and left the room. The door shut soundlessly behind me, and I shuffled across the deck of the ship. Despite the salty ocean breeze—which smelled all the more fresh this far from land—I kept my head low and stared at my feet.

“What could Uncle even do about this?” I muttered to myself. “Will he at least contact Father and tell him what I’ve discovered?”

Father might even ask Melroc to turn the sky-ship around instead of continuing on our journey. If that happened, no one might ever find the Blood of the Sun.

At that thought, I stopped in midstep. The Blood of the Sun had been missing for thousands of years. Tales told it was stolen away from the amüli queen Bertrys Aneys some thousands of years ago after she had used it to conquer much of Vasmyl, the eastern continent where we were headed.

The person who hid the gem varied in each version of the tale. Some claimed the thief was Bertrys’s husband, Prince Ayev. She had murdered his entire family to secure the throne for herself and had wed him to prevent the people from revolting against her rule. I didn’t doubt Ayev might’ve been angry enough to steal it, but I figured if he had nabbed it, he would have used it against her. Other versions of the lore suggested a jilted lover had stolen it, or a friend had taken it at Bertrys’s request, for she feared her enemies might turn its power against her.

I stared up at the deck where Lord Loudrum and the others waited for me, then I spread my wings and took to the sky. Whoever had taken the gem—and why—was no longer important. What mattered was finding it, and soon. Even if Father ended up arresting Loudrum for breaking into the Catacombs, there was still the missing prisoner to deal with. We’d still need the stone to find whoever that was.

I landed and strolled over to the group, doing my best to look embarrassed. “I’m sorry, my lord,” I apologized in my humblest voice. “I... had to use the privy.”

Lord Loudrum, who oversaw the others while they scrubbed the deck, narrowed his glittering green eyes. “Privy. Right. Go scrub the decks.” He jerked his head over to the other deckhands. “You’re too scrawny to help anywhere else. Grab a bucket and get to work.”

Before I could ask where the buckets or rags were, the lord stalked away, his lean form and willowy, tawny wings vanishing among the sailors working this deck. I craned my head around, trying to figure out how many decks we had to scrub. To my relief, more deckhands worked on other disks of clouds, which meant I probably wouldn’t have to clean all of them.

“You look confused,” a girl near my age said.

She held a bucket and offered an enormous, friendly grin. When I inhaled her blood-scent, the barest hint of flavor came to me: sweet, fresh summer grains and pine nuts. She wore a tattered brown shirt, which was so dirty it might have once been green, and a pair of linen trousers that reached her ribcage. Her sandy hair was tied back, but choppy strands framed her freckled face. The ashy wings of a mourning dove fanned opened and closed behind her.

“Oh, hello.” I glanced at the pail in her hand. “Where do I find the buckets and the rags so I can help out?”

“You can share with me. There’s a spare rag in my bucket.”

She gestured toward the edge of the platform, and we crouched down on our hands and knees. I folded my wings and fished a rag out of the murky water, wrung it out, wadded it up, and did as my companion—scrubbing forward then backward in long, straight lines.

“I’m Frendyl,” I said.

“My name’s Jaecrel, but my friends call me Jae.” She cast me another large grin. “Where are you from?”

“Drüssyevoi.”

“So you’re new, then, huh?”

I shrugged a shoulder. “Just joined this morning. How about you?”

She scooted down and continued to scrub. “I’m from Jaemyvyk myself,” she said, her voice carrying well across the deck even though we worked only a few yards apart. Her wings flexed open and closed as she moved. “I’ve been with the crew for a few months now.”

We fell into companionable silence as we worked, though Jae occasionally jumped to her feet to fetch fresh water. The monotony of the chore soon became all I could focus on, and when I realized the movement began lulling me into sleepiness, I shook my head.

“Looks like it’s time for a break,” Jae said, flashing me a smile.

“How did you end up on the ship?” I asked her. The two of us walked over and sat on the edge of the platform. I dangled my legs in the open air and leaned back on my hands with a smile. The wind up here was so fresh, so wonderful, so free. The constant floating felt quite odd, as the ship would move up and then sink before the casters forced it higher. From what I could tell, they were trying to mimic birdlike flight by using the rise-and-fall motion to save energy.

“Captain Krune caught me trying to steal food over in Jaemyvyk,” Jae said. “He asked me to join his crew, said I’d get three squares a day, a place to sleep, and I’d even earn some money.”

“He’s a good man.”

Jae bobbed her head and broke off a heel of stale bread she retrieved from inside her shirt. “He is. You’re related to him, aren’t you?”

I chuckled. “Is my blood that obvious?”

“It’s not just the blood.” She paused and stretched her arms while she chewed. “Your eyes and wings, mostly. You two have the same of both.” She stared at me for a few moments and then ducked her gaze away, as if realizing how long she’d been gawking. “Anyone can tell you’re a Krune. So tell me, why’re you here, then?”

“Captain Melroc took me on as his apprentice.”

“That seems... odd. He’s a captain; you’re the son of a lord, right?”

“Yeah. My father is high lord of Drüssyevoi.”

“So... shouldn’t you be back home, ordering people around?”

The way she said it was so blunt and cold that I bit back a frown. “I guess I could be, but I wanted to see the world.”

“Why?”

“Because I want to be a knight someday.”

“Sounds interesting.” She stood and stretched her wings and arms. “We should probably get back to work.”

Part of me wanted to flop over and groan, but I pushed the urge aside. If I was going to be a knight one day, I needed to do all in my power to find and capture the amüli Loudrum had freed.

“Is there anyone else new on the ship?” I asked Jae.

She shook her head. “Nope. Just you.”

I sank back to my aching knees and pulled the rag from the bucket of milky water. Back and forth, back and forth, scoot back, dip the rag, and again, scrub back and forth.

When the sun began to sink and the sailors called out for the last of their supplies from the deck, I slowly pulled myself to my feet, hoping the plan I’d formulated about Loudrum would work. I’d been on my hands and knees all day, and my back was stiff. My kneecaps stung, and my shins ached as though I’d walked the ‘Combs fifteen times over. Soon, I’d need to clean out Uncle Melroc’s chambers. I just hoped I’d have enough energy left for that.

Jae sat on a sealed barrel full of clean water. Thump, thump, thump—her heels kicked against the side of the barrel, matching the beat of my Center. “Are you going to stick with us deckhands tomorrow?”

“I think so.”

“You’re going to hurt in the morning. Anyone who just starts out hurts for a while. It’s okay, though. Trust me. You’ll build muscles, then you’ll be fine.” She rolled her left arm, and I caught sight of her blita—the black-and-white tattoo every amüli was given at birth—on her left shoulder. Like my own, hers had a large black swirl, but minute differences set ours apart. Her black swirl aimed upward, while mine hooked downward and met up with a white one.

“Is every day like this?”

“No. We clean the deck once a week, but we have other chores.”

“Such as?”

“We rotate helping in the galley to make meals, and one of us cleans the latrines every day. But it’s a different person each time, so you won’t get stuck with that all the time.”

“Anything else?”

“Odd jobs. The barnacles are getting pretty bad, so we might be doing that soon.”

“Barnacles? But we’re in the sky, not the water.”

“Sky barnacles, genius. They usually only collect around pockets of warm air over the ocean, and they’re not violent or anything. They’re just... difficult to clean off. The casters complain they eat too much of the magic.”

“Eat magic? Sounds exciting.”

“Sure is.” She stuck a finger up her nose and wiggled it around, then pulled out a booger and tossed it over the edge of the platform.

I gawked and recoiled. “Ugh! That’s gross!”

“It’s the barnacles! I think some got up my nose! Want to see a bigger one?”

“No!” Still, I laughed.

Jae’s eyebrows jumped up and vanished into her shaggy hair, as if I’d offended her. “No way. Why not? It’s the biggest you’ll ever see, I swear it.”

“That’s so gross. You’re a lady!”

“Oh, don’t worry.” She punched me in the arm and winked. “You can still be my friend, even if you don’t know anything about us ladies.”

I wasn’t sure how long the voyage would last, but at least I had someone to talk to. The work and Loudrum’s blood-scent had kept my mind busy, but as the day waned, Mizen’s absence weighed heavily on me. Of course, I couldn’t tell Jae about the Blood of the Sun or the amüli who had invaded our estate or even my suspicions of Lord Loudrum. Mizen, though, I could have talked to about anything, and I yearned to fly through the canyon with him as we often did. Silence between us always comforted me.

“I’d love to stick around,” I said, “but I really need to go clean the captain’s quarters.”

“Do you have to wash the chamber pot?”

“Yes.”

She wrinkled her nose. “Gross.”

“Says the one who digs out snot.”

“Hey, that’s a life skill. It’s something everyone should practice.”

I rolled my eyes and headed off, stretching my arms and wings. The kinks were already a nightmare, and I had a feeling that Jae was right about how achy I’d be in the morning. At least I’d sleep well.

Once I arrived at my uncle’s cabin, I knocked on the cloud door. No one answered, so I let myself in. The door to his personal chambers swirled open, and a bucket of lye water, along with a few cloths for scrubbing, had been left out in the empty cabin. No doubt they were meant as an invitation. I exhaled, deciding to dive into work. I’d talk to him about my plan when he returned.

Every muscle and joint ached as I scrubbed and cleaned. My exhaustion tempted me straight to bed once I finished, yet a sharp pain in my gut reminded me to nab some food.

By the time I left the captain’s cabin for supper, Melroc was still gone, and no one I asked had seen him. By the time night was an hour old, weariness had overcome me. My plan had to work, but I needed Melroc’s help to pull it off. I just hoped he’d be willing to listen to me in the morning.

—-END OF SPECIAL SNEAK PREVIEW—-

GRAB THE FULL EBOOK TODAY!

FIND LINKS TO YOUR FAVORITE RETAILER HERE:

FRENDYL KRUNE Series at Evolved Publishing

~~~

END OF FILE. THANK YOU.